To the editor:

FLT3-activating mutations are one of the most frequent genetic aberrations in acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1 Internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) mutations are associated with the worst prognosis, whereas tyrosine kinase domain (FLT3/TKD) mutations have an uncertain prognostic impact, but represent a resistance mechanism to FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibitors (FLT3 TKIs).2 Although there is evidence that FLT3 TKIs have improved outcomes for AML patients, their development has been impeded by numerous obstacles in the past 15 years. The first generation of FLT3 TKIs, such as lestaurtinib, midostaurin, and sorafenib, were multikinase inhibitors that lacked potency.3-6 Conversely, quizartinib, a highly potent TKI against type III receptor tyrosine kinases, also inhibits c-Kit, exacerbating myelosuppression.7 Others failed because of short in vivo half-lives.8 Last, sustained FLT3 inhibition can result in the emergence of resistance-conferring FLT3/TKD point mutations, most often at residue D835.9

Gilteritinib (previously referred to as ASP2215) is a pyrazinecarboxamide derivative being studied in AML clinical trials because of its potential selectivity, potency, and activity against all classes of FLT3-activating mutations (see supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site). In this study, we investigated the activity of gilteritinib and compared it with 4 other FLT3 TKIs in clinical development: midostaurin, sorafenib, quizartinib, and crenolanib.10-13

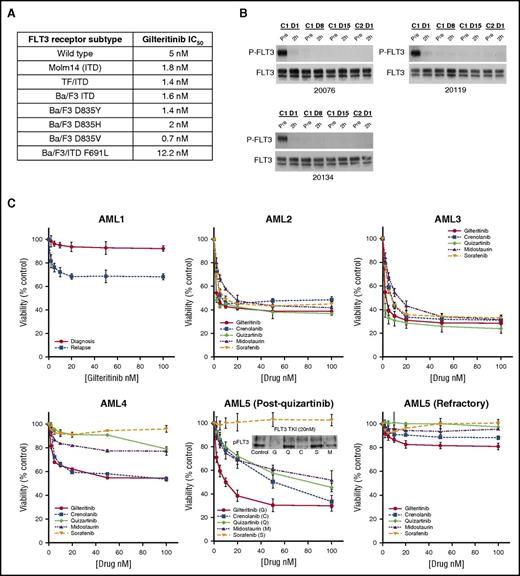

We tested the inhibitory activity of gilteritinib against different forms of FLT3 in leukemia cells by immunoblotting (summarized in Figure 1A; representative blots shown in supplemental Figure 2A). When tested in media, the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) for inhibition of the wild-type receptor was 5 nM; the ITD-mutated form ranged from 0.7 to 1.8 nM depending on the cell context. In plasma, the IC50 for inhibition of the FLT3-ITD receptor ranged from 17 to 33 nM (supplemental Figure 2B). Using a panel of FLT3 point mutations known to confer resistance to type II inhibitors, such as sorafenib and quizartinib, we also found that gilteritinib had similar degrees of inhibitory activity against commonly identified TKD mutations (Figure 1A). It also had activity against the gatekeeper mutation at F691, although at a relatively higher IC50.

Anti-leukemic activity of gilteritinib. (A) IC50 values for different FLT3 receptor subtypes. Cells expressing the indicated subtype were incubated with ASP2215 for 1 hour at increasing concentrations in RPMI/10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), analyzed by immunoprecipitation/immunoblotting for phospho- and total FLT3, and followed by densitometry. SEMK2 cells express wild-type FLT3, Molm14 cells express a 21-bp ITD mutation, and TF/ITD and Ba/F3 ITD cells express a transfected FLT3 construct containing an 18-bp ITD (see supplemental Methods). Ba/F3 cell lines with the indicated mutant FLT3 isoforms were generated by transfecting the murine lymphocyte Ba/F3 line with constructs expressing the FLT3 receptor (non-ITD–containing, except for the F691L variant) containing the indicated single point mutation. Each IC50 value was calculated from multiple experiments. (B) Gilteritinib inhibits FLT3 phosphorylation in vivo. Plasma samples collected at trough time points from 3 patients enrolled in a gilteritinib study were incubated with Molm14 cells for 1 hour. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were used to detect phospho-FLT3 and total FLT3 at these time points. (C) FLT3 TKI sensitivity ex vivo in primary patient samples is dependent on FLT3 mutation type. (AML1) A comparison of the cytotoxic effects of gilteritinib against 2 samples from patientAML1: 1 collected at diagnosis and the other at relapse. (AML2, AML3) Patients with relapsed AML and a high FLT/ITD allelic burden, respectively. (AML4) A patient with both FLT/ITD and TKD (D835Y) mutations, which confer resistance to type II inhibitors sorafenib and quizartinib when compared with counterparts lacking a FLT3/TKD mutation. (AML5) A patient with a high FLT3-ITD allelic burden who developed a FLT3/TKD (D835I) mutation after being treated with quizartinib. The MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium) data in were performed with the patient’s blasts after progression on quizartinib and indicate that gilteritinib was the most potent of all 5 FLT3 TKIs against this patient’s blasts. The immunoblot shows the level of phospho-FLT3 expression in blasts after a 1-hour treatment with 20 nM of each FLT3 TKI in RPMI/10% FBS. The patient then enrolled on a crenolanib study and was refractory and was noted to have a new F691L gatekeeper mutation. (AML5 refractory) The MTT assay was repeated with the patient’s blasts after treatment with crenolanib and shows the resistance conferred by the F691L mutation. Supplemental Table 1 provides the mutation profiles of these patients.

Anti-leukemic activity of gilteritinib. (A) IC50 values for different FLT3 receptor subtypes. Cells expressing the indicated subtype were incubated with ASP2215 for 1 hour at increasing concentrations in RPMI/10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), analyzed by immunoprecipitation/immunoblotting for phospho- and total FLT3, and followed by densitometry. SEMK2 cells express wild-type FLT3, Molm14 cells express a 21-bp ITD mutation, and TF/ITD and Ba/F3 ITD cells express a transfected FLT3 construct containing an 18-bp ITD (see supplemental Methods). Ba/F3 cell lines with the indicated mutant FLT3 isoforms were generated by transfecting the murine lymphocyte Ba/F3 line with constructs expressing the FLT3 receptor (non-ITD–containing, except for the F691L variant) containing the indicated single point mutation. Each IC50 value was calculated from multiple experiments. (B) Gilteritinib inhibits FLT3 phosphorylation in vivo. Plasma samples collected at trough time points from 3 patients enrolled in a gilteritinib study were incubated with Molm14 cells for 1 hour. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were used to detect phospho-FLT3 and total FLT3 at these time points. (C) FLT3 TKI sensitivity ex vivo in primary patient samples is dependent on FLT3 mutation type. (AML1) A comparison of the cytotoxic effects of gilteritinib against 2 samples from patientAML1: 1 collected at diagnosis and the other at relapse. (AML2, AML3) Patients with relapsed AML and a high FLT/ITD allelic burden, respectively. (AML4) A patient with both FLT/ITD and TKD (D835Y) mutations, which confer resistance to type II inhibitors sorafenib and quizartinib when compared with counterparts lacking a FLT3/TKD mutation. (AML5) A patient with a high FLT3-ITD allelic burden who developed a FLT3/TKD (D835I) mutation after being treated with quizartinib. The MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium) data in were performed with the patient’s blasts after progression on quizartinib and indicate that gilteritinib was the most potent of all 5 FLT3 TKIs against this patient’s blasts. The immunoblot shows the level of phospho-FLT3 expression in blasts after a 1-hour treatment with 20 nM of each FLT3 TKI in RPMI/10% FBS. The patient then enrolled on a crenolanib study and was refractory and was noted to have a new F691L gatekeeper mutation. (AML5 refractory) The MTT assay was repeated with the patient’s blasts after treatment with crenolanib and shows the resistance conferred by the F691L mutation. Supplemental Table 1 provides the mutation profiles of these patients.

In addition to FLT3, data from the kinase selectivity assay (supplemental Figure 1) indicated that gilteritinib has activity against receptor tyrosine kinase Axl, which may modulate the activity of FLT3 in AML.14 We confirmed that the drug inhibits Axl (supplemental Figure 2C), although the IC50 against this receptor is 41 nM, approximately 20-fold higher than what we observed for the ITD-mutated FLT3 receptor.

One obstacle in the development of FLT3 inhibitors has been the inability to achieve sustained FLT3 inhibition in vivo.8,15,16 We used the plasma inhibitory activity assay to confirm sustained in vivo inhibition,4 with plasma collected at trough time points from patients receiving gilteritinib on a phase 1/2 study (Dose Escalation Study Investigating the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics of ASP2215 in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia, #NCT02014558). Figure 1B shows that plasma from 3 patients receiving a daily dose of 120 mg gilteritinib completely inhibited the phosphorylation of the FLT3-ITD receptor in Molm14 cells.

We next compared the cytotoxic effects of gilteritinib vs other FLT3 TKIs in FLT3-expressing leukemia cell lines and primary patient samples. Gilteritinib had a response profile typical of FLT3 inhibitors against the FLT3-ITD–expressing Molm14 and MV4-11 cell lines and a modest effect against SEMK2 cells, which overexpress wild-type FLT3 (supplemental Figure 3). In HL60 cells, which express low levels of wild-type FLT3, there was no cytotoxic effect. Accordingly, in primary samples obtained from 4 AML patients lacking FLT3 activating mutations, no effect was observed, although this small sampling is admittedly not a representation of all AML subtypes (supplemental Figure 4).

We previously reported the difference in responsiveness of diagnostic vs relapsed FLT3-ITD AML samples,17 likely from the more polyclonal nature of the disease at diagnosis.18 Consistent with this finding, blasts from patient AML1 collected at diagnosis failed to respond to gilteritinib, whereas blasts collected at relapse from the same patient 8 weeks later displayed a cytotoxic response (Figure 1C); therefore, we focused on specimens collected at relapse. Two representative samples of the 8 tested, from patients AML2 and AML3, displayed the typical cytotoxic response to all 5 inhibitors (Figure 1C). Of particular interest were samples that had been collected from 2 patients (AML4 and AML5) following treatment with FLT3 TKIs. The cytotoxicity profiles of these 2 samples exposed to the different inhibitors are consistent with previous reports on relative resistance conferred by TKD mutations to FLT3 TKIs (Figure 1C).19,20 Patient AML4 presented with a FLT3-ITD mutation at diagnosis and was refractory to induction and salvage chemotherapy. He then achieved a complete response with incomplete count recovery with quizartinib that was followed with an allogenic transplant. At relapse 6 months later, he initially responded to treatment with sorafenib, but his disease progressed with a FLT3-D835Y mutation. The results (Figure 1C) show that only gilteritinib and crenolanib were effective at inducing a cytotoxic response in this relapse sample. Likewise, patient AML5 was refractory to conventional chemotherapy and responded initially to quizartinib before her disease developed a D835I mutation. As shown in Figure 1C (AML5 post-quizartinib), gilteritinib was the most effective TKI at this point and was the only TKI to inhibit FLT3 at a concentration of 20 nM by immunoblot. Patient AML5 was then referred to a clinical trial for crenolanib and progressed after several weeks of treatment. The blasts now harbored a mutation at F691L and were resistant to all inhibitors, although gilteritinib produced a weak response (Figure 1C, AML5 refractory). The clinical characteristics of these AML patients are listed in supplemental Table 1.

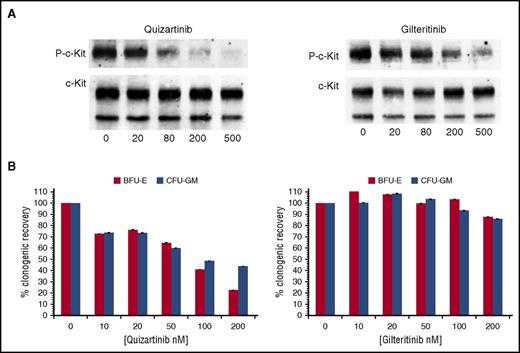

Inhibitors of FLT3 are often found to have activity against the structurally related receptor c-Kit.7,13,21 This has important clinical implications because c-Kit is essential for normal hematopoiesis, and even partial inhibition of this receptor can contribute to marrow suppression.7,22-24 Midostaurin, quizartinib, and (to a lesser degree) crenolanib are known to also inhibit c-Kit.7,13,25 Because quizartinib is the most potent FLT3 TKI of the 3, we compared gilteritinib and quizartinib against c-Kit in immunoblot assays using the erythroleukemia line, TF-1. As shown in Figure 2A, gilteritinib has an IC50 against wild-type c-Kit of 102 nM, 2 orders of magnitude greater than that of mutant FLT3. As expected, it had minimal effects on hematopoiesis, as shown in progenitor cell assays using bone marrow from healthy donors (Figure 2B). Even with an IC50 of 102 nM in vitro, partial inhibition of c-Kit might be achievable at very high doses in vivo.

Inhibition of c-Kit and effects on erythropoiesis by quizartinib and gilteritinib. (A) TF-1 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of either quizartinib or gilteritinib in RPMI/10% FBS for 1 hour. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were performed to detect the phosphorylation status of c-Kit and total c-Kit. (B) Mononuclear cells isolated from normal donor bone marrow were plated at 105 cells/mL in MethoCult. Increasing concentrations of quizartinib or gilteritinib were added. Counts for colony-forming unit-granulocyte, monocyte (CFU-GM) and burst-forming unit-erythroid (BFU-E) colonies were done after 10 to 12 days of incubation (n = 3). P-c-Kit, phosphorylated c-Kit.

Inhibition of c-Kit and effects on erythropoiesis by quizartinib and gilteritinib. (A) TF-1 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of either quizartinib or gilteritinib in RPMI/10% FBS for 1 hour. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were performed to detect the phosphorylation status of c-Kit and total c-Kit. (B) Mononuclear cells isolated from normal donor bone marrow were plated at 105 cells/mL in MethoCult. Increasing concentrations of quizartinib or gilteritinib were added. Counts for colony-forming unit-granulocyte, monocyte (CFU-GM) and burst-forming unit-erythroid (BFU-E) colonies were done after 10 to 12 days of incubation (n = 3). P-c-Kit, phosphorylated c-Kit.

Investigators seeking to develop clinically useful FLT3-TKIs have encountered numerous obstacles, including suboptimal pharmacokinetics, poor selectivity and potency, myelosuppression, prolongation of the QT interval, and resistance-conferring FLT3 point mutations. Based on these data, gilteritinib overcomes most of the obstacles thus far encountered. Its in vitro efficacy is equal to or greater than that of the other TKIs, it inhibits the FLT3/TKD mutations that are predominantly responsible for resistance, it is unlikely to be myelosuppressive, and it achieves sustained inhibition of FLT3 in vivo. Gilteritinib also has activity against Axl, which may counteract a mechanism of resistance.14 It is unclear whether in vivo levels of the drug would be sufficient to achieve control of a clone with an F691 gatekeeper mutation, and this remains a potential weakness. Nevertheless, our findings indicate that gilteritinib may be the most useful FLT3 TKI developed to date; it has already been entered in registration trials.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Authorship

Acknowledgment: This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (NCI Leukemia Specialized Programs of Research Excellence P50 CA100632).

Contribution: L.Y.L. and M.L. designed the study, performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. D.H., T.R., S.C.S., J.R.R., and B.N. performed experiments. D.S. contributed to study design and helped edit the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.L. receives research funding from Novartis and Astellas and serves as a consultant for Novartis, Daiichi-Sankyo, Astellas, and Arog. The remaining authors declare no competing financial conflicts.

Correspondence: Mark Levis, Kimmel Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, 1650 Orleans St, Room 2M44, Baltimore, MD 21287; e-mail: levisma@jhmi.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal