Why are some patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) resistant to tyrosine kinase therapy? In this issue of Blood, Warfvinge et al use single-cell approaches to characterize the shifting subpopulations of CML stem cells associated with response and resistance.1

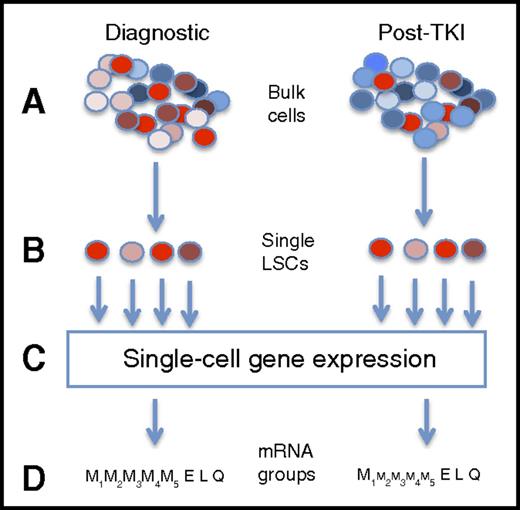

Capturing single-cell mRNA expression before and after TKI therapy. This is a highly simplified presentation of the experimental design. First, bulk mononuclear cells from CP-CML patients at diagnosis and after TKI therapy (A) were flow cytometry sorted into single cells based on a group of surface antigens associated with the leukemia stem cell state (B). In this figure, LSCs are in shades of red, whereas normal stem cells are in shades of blue. Gene mRNA levels for 95 genes were performed on each cell (C). From these gene expression patterns, 7 different cell subtypes were inferred, including 4 myeloid groups (from less to more differentiated), and 1 group each with erythroid, lymphoid, and quiescence expression patterns. After therapy, residual CML cells were biased toward some pathways (schematically shown by size of font), the largest with inferred quiescence state, with the CD45RA−cKIT−CD26+ phenotype appearing to be the population mostly associated with TKI resistance.

Capturing single-cell mRNA expression before and after TKI therapy. This is a highly simplified presentation of the experimental design. First, bulk mononuclear cells from CP-CML patients at diagnosis and after TKI therapy (A) were flow cytometry sorted into single cells based on a group of surface antigens associated with the leukemia stem cell state (B). In this figure, LSCs are in shades of red, whereas normal stem cells are in shades of blue. Gene mRNA levels for 95 genes were performed on each cell (C). From these gene expression patterns, 7 different cell subtypes were inferred, including 4 myeloid groups (from less to more differentiated), and 1 group each with erythroid, lymphoid, and quiescence expression patterns. After therapy, residual CML cells were biased toward some pathways (schematically shown by size of font), the largest with inferred quiescence state, with the CD45RA−cKIT−CD26+ phenotype appearing to be the population mostly associated with TKI resistance.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy has revolutionized the care of chronic phase (CP) CML, giving most patients a near normal life expectancy.2 Therapy is so effective that some patients with a prolonged deep molecular response may successfully discontinue therapy with disease relapse.3 However, a small subset (∼10%-30%) of patients either do not respond to TKIs, or initially respond, then relapse. In roughly half of these cases, resistance is due to a single-point mutation in the ABL kinase domain of the fusion BCR-ABL gene, abrogating the inhibitory powers of the TKI.4 Once resistance occurs, the addition of a new TKI can engender a subsequent response, but often these are short-lived, with another relapse often featuring a different ABL mutation. Patients with this pattern of continued resistance have a higher likelihood of undergoing transformation that is poorly controlled by TKIs, and is often fatal without the intervention of allogeneic transplantation.

Relapse is the bane of cancer therapy, with many patients initially responding to therapy, then relapsing, often while on the therapy that originally yielded a response. If cancer is a monolith of genetically identical cells, this behavior is difficult to figure out, unless new mutational events occurred during therapy making these cells resistant. However, next generation sequencing (NGS) has shown that cancers are often made of many related but distinct clones,5 so that the response of therapy, then relapse, can be seen through the lens of natural selection, whereby sensitive populations topple with therapy, but where their demise allows space and resources for a preexisting resistant clone. In this view, resistance is simply a natural, though unwanted, consequence of therapy.

If cancer is an ecosystem, subject to the same Darwinian rules as the rest of life, how does one study it? Our current method of performing genetic analyses (mutation genotyping, messenger RNA [mRNA] levels, methylation, etc) uses “bulk” samples of unfractionated cells. This may contain malignant cells, some normal ones, and in the malignant cells, many different clones. Thus, an understanding of the cancer ecosystem is limited by being forced to average the genetics and biology across all comers. By analogy, imagine we are trying to study the ecosystem of a swamp. We first drain the swamp, then put it in a blender, and then take up the bits and try to reassemble the constituents of the swamp. There may be a lot of duck parts, a few frog pieces, and look, a chunk of lobbyist! Much better would be to interrogate, count, and measure each unit of the swamp, to give the precise number of ducks, frogs, and lobbyists. By interrogating each closely, you may find out details suggesting each role and activity in the swamp. Indeed, single-cell genotyping has shown that the clonal structure of leukemia is far more complex than estimated by NGS of bulk samples.6

Can a single-cell approach help us understand resistance in CML? The study by Warfvinge and colleagues suggests so. In order to define the type of cell responsible for resistance, and its molecular characterization, the authors separated bulk samples from diagnostic and treated samples into distinct cell populations based on multiple cell surface markers associated with the CML leukemia stem cell (LSC) (see figure). Next, single-cell mRNA was performed on Lin−CD34+CD38−/low cells for a set of 95 genes predetermined to be involved in CML biology. Cell marker data and gene expression patterns inferred a heterogeneous LSC population that could be found at diagnosis (n = 13 patients) and followed in a subset of patients (n = 10) who had persistent cytogenetic evidence of CML while on TKI therapy. In total, roughly 1000 cells were assayed in each of the diagnostic, TKI-resistant, and normal bone marrow categories.

Nonsupervised clustering revealed that 7 different cell populations were inferred, based on expression of genes involved in the cell cycle, myeloid and lymphoid biology and differentiation, and quiescence. Four myeloid subpopulations were inferred, based on cell cycle activity and commitment to differentiation. In addition, populations suggesting lymphoid and erythroid biology were noted, as well as a quiescent subpopulation. Cells were subsequently sorted based on surface antigens found in the subpopulation expression analysis (eg, CSF3R in the myeloid II-IV groups) and underwent single-cell proliferation and differentiation experiments, correlating the inferred biology to actual (at least, in vitro) behavior. After therapy, residual CML subpopulations shifted in a logical pattern, with late-myeloid populations declining with TKI exposure, with the corresponding enrichment of early myeloid and especially the quiescence subpopulation. The CD45RA−cKIT−CD26+ phenotype appeared to be the population mostly associated with TKI resistance.

There are some limitations in this study that come with the territory of single-cell work. First, it is technically and fiscally hard to perform single-cell studies on large cohorts because each sample generates thousands of cell assays. Second, controls to test for reproducibility and technical and biological noise are a major issue in single-cell work because each cell is “one and done.” Unfortunately, mRNA levels can change with sample handling and time, so that one can find patterns in gene expression that are merely reproducible noise.7 However, the findings of this study are reassuringly consistent with previous work. For example, kinetic measurements showed initial rapid elimination of CML cells, then a slow decline, presumably from early clearance of mature cells, followed by a slow decline in an immature pool.8 Moreover, the finding of a quiescent signal in residual cells, especially in those with low KIT levels, is in keeping with a large body of work where quiescence appears quite important in CML stem cell survival with exposure to TKI.9

Cancer is a complex ecosystem of normal cells, environment, and multiple cancer clones that compete and cooperate. It is a messy swamp, but potentially penetrable, 1 cell at a time.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal