Thrombolytic therapy with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of acute ischemic stroke in 1996 and remains the only approved pharmacologic treatment for this condition.1 Although considered the standard of care, tPA is underused in stroke patients for several reasons, including the strict eligibility criteria, narrow treatment window, and risk of life-threatening bleeding.1,2 In this issue of Blood, Simão et al present findings using a mouse model of cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury that indicate some adverse effects of tPA therapy in stroke patients may be mitigated by blocking the protease plasma kallikrein (PKal).3

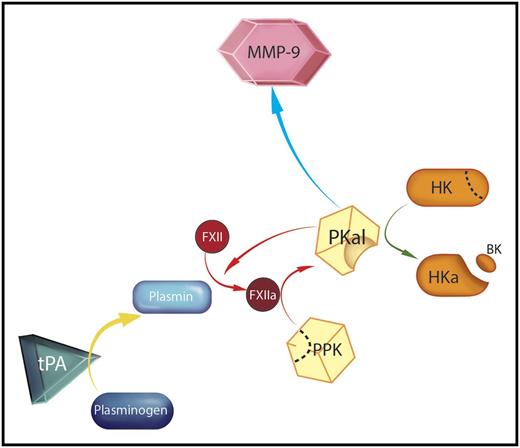

Mechanism for tPA-mediated activation of plasma prekallikrein (PPK). A therapeutic dose of tPA converts plasminogen in plasma to plasmin (yellow arrow) in a suitably high concentration to facilitate generation of the protease factor XIIa (FXIIa) from its precursor FXII. FXIIa then initiates reciprocal activation of PPK to PKal, as indicated by the red arrows. PKal may contribute to the adverse side effects associated with tPA therapy through several mechanisms, including cleavage of high molecular weight kininogen (HK) to cleaved kininogen (HKa), liberating bradykinin (BK, green arrow), activation of the matrix metaloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) system (blue arrow), and sustained FXII activation. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

Mechanism for tPA-mediated activation of plasma prekallikrein (PPK). A therapeutic dose of tPA converts plasminogen in plasma to plasmin (yellow arrow) in a suitably high concentration to facilitate generation of the protease factor XIIa (FXIIa) from its precursor FXII. FXIIa then initiates reciprocal activation of PPK to PKal, as indicated by the red arrows. PKal may contribute to the adverse side effects associated with tPA therapy through several mechanisms, including cleavage of high molecular weight kininogen (HK) to cleaved kininogen (HKa), liberating bradykinin (BK, green arrow), activation of the matrix metaloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) system (blue arrow), and sustained FXII activation. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

tPA catalyzes conversion of plasminogen to plasmin (see figure, yellow arrow), a key mediator of fibrin clot degradation. Thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke was first proposed in the 1960s, but it became clear early on that the promising results obtained with this strategy in myocardial infarction would not be realized in stroke patients.2 Sudden reperfusion of ischemic brain may lead to catastrophic hemorrhagic transformation within the injury zone. Several contributing factors have been identified, including the length of time from symptom onset to initiation of therapy. Approval of tPA for use in ischemic stroke was based primarily on results from the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study,4 which showed benefit when therapy was initiated within 3 hours of symptom onset. Subsequent results from the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study have indicated that therapy is of benefit out to 4.5 hours.5 Even when these recommendations are followed, hemorrhagic transformation occurs in 3% to 8% of cases.1,2 Results of a recent meta-analysis illustrate the dilemma.2 Although thrombolysis improves neurologic function 3 months postevent, it significantly increases intracranial hemorrhage and early mortality. Largely because of this, there is little effect on overall mortality.

In addition to compromising clot integrity, tPA produces other effects that may complicate reperfusion in stroke patients. Plasmin activates the kallikrein-kinin system (KKS).6 The KKS includes the plasma proteins PPK and FXII.7 When the KKS is activated, PPK and FXII are converted to the enzymes PKal and FXIIa (see figure, red arrows). Among its functions, PKal catalyzes cleavage of a third component of the KKS, high-molecular-weight kininogen, generating the peptide BK (see figure, green arrow). BK induces vasodilatation and increases vascular permeability and edema formation.6,7 Infusion of tPA into patients with myocardial infarction increases PKal and BK generation.8 Local production of BK in a stroke patient receiving tPA could contribute to loss of blood vessel and blood-brain barrier integrity, leading to tissue damage and increased risk of hemorrhagic transformation.

Simão et al postulated that plasmin-mediated activation of the KKS contributes to ischemia reperfusion injury during tPA treatment of acute stroke. They tested this in a mouse model in which tPA is administered 2 hours after induction of middle cerebral artery occlusion. tPA-treated mice had increased cerebral infarct volumes, edema, and hemorrhagic transformation compared with untreated mice. These adverse effects were ameliorated if the animal received a PKal inhibitor 15 minutes before tPA infusion. Mice lacking PPK or FXII demonstrated resistance to the adverse effects of tPA, consistent with a role for the KKS in reperfusion injury. An important observation was that tPA improved brain reperfusion in PPK-deficient mice compared with wild-type animals. This suggests PKal inhibition not only blocks the adverse effects of tPA therapy, but also potentiates its beneficial thrombolytic effect.

Based on these impressive results and in vitro experiments with plasma and purified proteins, Simão et al propose a model in which plasmin generated by tPA infusion activates FXII (see figure). FXIIa then catalyzes PPK conversion to PKal, which may compromise vascular integrity by several mechanisms. In addition to the deleterious effects of BK, PKal will generate additional FXIIa, which can promote thrombus formation through its effects on thrombin generation.7 MMP-9 was previously shown to contribute to bleeding in tPA-treated mice after middle cerebral artery occlusion.9 In the current study, increased MMP-9 activity produced by tPA treatment was blocked by the PKal inhibitor, indicating that PKal contributes to MMP-9 activation in this setting (see figure, blue arrow).

This work identifies PKal and FXIIa as contributors to tPA-induced ischemia reperfusion injury in mice. Plasmin-mediated activation of the KKS was demonstrated in both mouse and human plasmas. PKal and FXIIa should, therefore, be considered targets for drug development to improve the safety of fibrinolytic therapy. Although traditionally classified as parts of the intrinsic pathway of blood coagulation, PPK and FXII are not required for hemostasis,7 and specific PKal or FXIIa inhibitors should not further compromise hemostasis in patients who may be prone to bleeding. A PKal inhibitor has already been approved for use in patients with hereditary angioedema, a group of conditions associated with KKS dysregulation.10 The stroke model used in this study is, obviously, not an ideal simulation of events that occur during strokes in humans, and more work must be done to establish the relevance of the findings for human disease. However, because PKal or FXIIa inhibitors should have excellent safety profiles, results with this model make a strong case for developing such agents for testing in stroke. If PKal inhibition in humans replicates the performance in mice, PKal inhibitors could be used to improve the safety and efficacy of fibrinolytic therapy in stroke (and perhaps other indications) and increase the number of patients eligible for tissue-sparing therapy.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.G. has received consultant fees from several pharmaceutical companies (Aronora, Bayer, Dyax, Ionis, Merck, Novartis, Ono) with an interest in inhibition of contact activation proteases for therapeutic purposes.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal