Abstract

With the increasing number of targeted agents for the treatment of patients with lymphoid malignancies comes the promise of safe and effective chemotherapy-free treatment strategies. A number of single agents, such as ibrutinib and idelalisib, have demonstrated impressive efficacy with a favorable toxicity profile. The observations that most responses are, however, partial and treatment duration is indefinite have stimulated interest in combinations of these agents with chemotherapy as well as with each other. Despite the promise of this approach, several recent trials of combinations of agents have been terminated as the result of life-threatening and fatal complications. Such outcomes have generated a cautionary note of the potential for unforeseen adverse effects that challenge drug development and mitigate against the empiric combination of such drugs outside of a clinical trial setting.

Introduction

A primary goal for the treatment of lymphoma patients is to develop therapeutic strategies that are highly effective, while associated with a favorable toxicity profile. Standard chemotherapy and, more recently, chemoimmunotherapy regimens have improved patient outcomes.1-4 However, these regimens are based on alkylating agents and other nonspecific cytotoxic drugs with associated acute and long-term adverse effects.

Over the past few years, an increasing number of effective and relatively well-tolerated targeted agents have provided the opportunity to develop regimens that are chemotherapy-free or, at least, limit the amount of nonspecific cytotoxic exposure as much as possible. One of the earliest attempts to treat previously untreated follicular lymphoma (FL) patients with a single targeted agent was published by Colombat et al in 2001.5 They treated 50 patients with low-tumor-burden FL with 4 weekly doses of rituximab and achieved an overall response rate (ORR) of 73%, with 20% complete remissions (CRs). Ghielmini et al6 subsequently reported the SAKK 35/98 trial in which previously treated and untreated patients with FL received 4 weekly doses of rituximab and then were randomized to either observation or 4 additional doses every 2 months. Long-term follow-up of the untreated patients who received prolonged induction showed that 45% were event-free at 8 years.7 The activity of rituximab in untreated patients with follicular and nonfollicular indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) has been supported by other groups.8-10

Biologic doublets

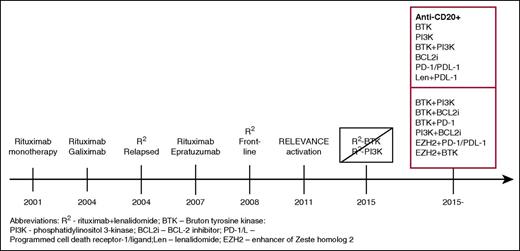

In 2004, investigators in the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB; now Alliance) began to study a series of biological doublets in FL in an attempt to improve on the single-agent activity of rituximab. In the first study, CALGB 50402, 61 patients with relapsed disease were treated with a rituximab and the anti-CD80 antibody galiximab.11,12 The regimen achieved an ORR of 72%, including 48% CRs, which suggested additive activity from the combination compared with published data with single-agent rituximab in untreated patients.5 Moreover, for low, intermediate, and high follicular lymphoma international prognostic index (FLIPI) score patients, the ORR and CR rates were 92% and 75%, 80% and 48%, and 55% and 27%, respectively. The progression-free survival for the low FLIPI patients was 75% at 3 years. The second doublet study, CALGB 50701, included rituximab and the anti-CD22 monoclonal antibody, epratuzumab. The ORR was 87%, including 42% CRs. Again, progression-free survival correlated with FLIPI score. Unfortunately, corporate decisions prevented further development of these antibodies. Nonetheless, both of these doublets achieved results similar to chemotherapy-based programs and were extremely well tolerated, paving the road for further chemotherapy-free approaches (Figure 1).

Timeline of the development of biologic combinations. This journey started with single-agent rituximab, which, when active in the relapsed setting was studied as initial treatment. Doublets of monoclonal antibodies were studied by CALGB investigators, which then were followed by their study of R2 in relapsed FL and, subsequently, as initial treatment. The addition of idelalisib to R2 was associated with prohibitive toxicity and, with ibrutinib, without a sufficient signal of improved efficacy to pursue further. Currently, numerous studies of doublets and triplets of targeted agents with or without an anti-CD20 are being conducted, with many more anticipated.

Timeline of the development of biologic combinations. This journey started with single-agent rituximab, which, when active in the relapsed setting was studied as initial treatment. Doublets of monoclonal antibodies were studied by CALGB investigators, which then were followed by their study of R2 in relapsed FL and, subsequently, as initial treatment. The addition of idelalisib to R2 was associated with prohibitive toxicity and, with ibrutinib, without a sufficient signal of improved efficacy to pursue further. Currently, numerous studies of doublets and triplets of targeted agents with or without an anti-CD20 are being conducted, with many more anticipated.

Although thalidomide was associated with limited activity in FL,13 several reports provided evidence of single-agent clinical activity with lenalidomide in a number of lymphoma histologies,14,15 and in preclinical experiments at least additive activity was seen when it was combined with rituximab.16,17 To explore the potential clinical efficacy of this combination, CALGB investigators initiated a randomized phase II trial in 91 patients with relapsed FL, allocating patients to single-agent lenalidomide in one arm with rituximab plus lenalidomide (R2) as the second arm.18 R2 was more effective than single-agent lenalidomide with an ORR and CR rate of 76% and 39% and 53% and 20%, respectively. The combination was well tolerated. Delivered dose intensity exceeded 80% in both arms. There were 53% grade 3 to 4 toxicities in the combination arm compared with 58% with single-agent lenalidomide, with 9% and 11%, respectively, being grade 4. The most common grade 3 to 4 adverse events (AEs) were neutropenia, fatigue, and thrombosis, which were similar in frequency between the arms.

These impressive results stimulated interest in pursuing R2 in previously untreated patients. SAKK investigators randomized untreated FL patients in need of therapy to rituximab monotherapy or R2 and achieved a better complete response rate with R2, but with greater toxicity. The data were premature to assess the impact on progression-free and overall survival.19 Martin et al20 from Alliance reported an ORR of 96%, unrelated to Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index, including more than 70% CRs. There were no grade 4 nonhematologic toxicities, and the most frequent grade 3 AEs were fatigue, pain, rash, and infection. Eighty-nine percent of patients were progression-free at 1 year. Using a different schedule in various indolent histologies, Fowler et al21 reported an ORR of 85% with 59% CR, and an ORR of 98% and 87% CR in their FL cohort. The regimen was considered to be well tolerated, with the only grade 3 to 4 nonhematologic toxicities occurring in >5% of patients being pain or myalgia (9%) and rash (7%). These experiences were considered sufficiently encouraging to support the large, recently completed, international phase III RELEVANCE trial comparing R2 with R-chemotherapy, which may redefine the initial treatment of patients with FL (NCT01476787).

An increasing number of agents in development directed at various cellular targets have achieved at least modest activity in FL.22-24 These observations have led to interest in combinations not only with cytotoxic chemotherapeutics but also with other targeted drugs in an attempt at improving efficacy.25,26 However, several clinical trials provide pause for caution when incorporating well-tolerated biological agents into a multiagent strategy. CALGB investigators previously reported impressive results in relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) with the chemotherapy regimen of liposomal doxorubicin, vinorelbine, and gemcitabine.27 Although well tolerated, initial studies with naked anti-CD30 (eg, SGN-30) monoclonal antibodies failed to achieve important single-agent activity.28,29 Nonetheless, preclinical data suggested greater potential when the antibody was used in combination with chemotherapy.30,31 Thus, CALGB investigators conducted a randomized phase II trial of doxorubicin, vinorelbine, and gemcitabine with or without SGN-30. In the first phase of the study, 16 patients received the combination to assess safety. Two patients required intubation for hypoxia, fever, and bilateral infiltrates after 2 to 3 cycles of therapy. Bronchoalveolar lavage failed to identify any organisms. One patient died despite antimicrobial agents and steroids, while the other recovered without steroids. In the randomized portion of the study, 3 of 7 patients developed grade 3 to 5 pneumonitis in the combination arm, one of which was fatal, leading to premature closure of the trial. Of note, all patients had a V/F polymorphism in the FcγRIIIa gene. The ORR was 63%, with little evidence of benefit from adding the antibody.

Brentuximab vedotin is an anti-CD30 antibody drug conjugate (ADC) that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on the basis of outstanding activity in patients with HL who had progressed after autologous stem cell transplantation,32 and relapsed or were refractory for anaplastic large-cell lymphoma.33 One path for its further development was to incorporate the ADC into a standard front-line chemotherapy program. Connors and coworkers updated results of a randomized phase I study including 51 patients with advanced HL randomized to either the combination of adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) or adriamycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (AVD), both combined with brentuximab vedotin (BV).34 Response rates were comparable at 95% and 96%, respectively. However, none of the AVD+BV patients experienced pulmonary toxicity compared with 44% of those who received ABVD+BV. The 3-year failure-free survival and overall survival favored the AVD+BV arm (83% vs 96%). These data suggested a positive effect of adding the biologic to standard chemotherapy, but an unfavorable interaction between the ADC and the bleomycin in ABVD. The relative efficacy of AVD+BV compared with standard ABVD will be determined by the results of the phase III ECHELON-1 trial (NCT01712490).

We need to be concerned not only about combining targeted agents with chemotherapy but also with each other as well. Given the various pathways that can be targeted within the B cell, the development of biological doublets and triplets has been of interest. Recent attention has focused on small molecules that target intracellular pathways. The current generations of Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors are highly active in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)35,36 and to a somewhat lesser extent in other histologies of lymphoma.22,37 The BTK inhibitor ibrutinib is FDA approved for the treatment of CLL, mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), and Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and the PI3K-∂ isoform inhibitor idelalisib, which is approved for relapsed and refractory FL, CLL, and small lymphocytic lymphoma. Although these agents are extremely active, they achieve primarily partial responses as single agents and require indefinite administration. They are also typically well tolerated. However, adverse effects of concern with ibrutinib include thrombocytopenia, atrial fibrillation, and bleeding. Although these have generally been mild to moderate in severity, fatal intracranial bleeding has been encountered. Idelalisib has been mostly associated with pneumonitis, diarrhea/colitis, and transaminitis.

Although little nonhematologic toxicity has been associated with combinations of R2 ibrutininb in relapsed CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma (C. Ujjani, Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, oral communication, January 7, 2016), the use of this regimen as initial treatment of FL was associated with a high risk of significant rash, and early appearance of additional malignancies.25 In contrast, the combination of the anti-CD20 ublituximab, the PI3K inhibitor TG-1202, and ibrutinib has been well tolerated without significant toxicities.26

Another agent of interest was entosplentinib, which targets the spleen tyrosine kinase. As a single agent, the response rate in 41 CLL patients was 61%, including 7.3% CRs.38 Toxicity analysis in a larger set of 186 patients identified a 16% incidence of dyspnea, which was grade 3 or worse in 6.5% of patients. Preclinical data assessing the viability of peripheral blood and bone marrow CLL cells, including those containing the 17p deletion, suggested synergy between entospletinib and idelalisib.39 Barr and coworkers40 conducted a phase 2 study combining entospletinib with idelalisib in 66 patients with relapsed or refractory CLL and NHL. As severe pneumonitis had occurred in only 3% of patients who had received idelalisib across clinical trials, the combination was theorized to be tolerable.22,36 The median exposure to the combination was 10 weeks. The regimen achieved an ORR of 60% in CLL, 36% in FL, and only 17% in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. However, 12 patients developed pneumonitis (18%), 11 of which were grade 3 or higher, characterized by the acute onset of dyspnea, cough, hypoxia, and computed tomographic finding of ground glass infiltrates, with fevers and chills. Five patients required ventilator support, and 2 patients died.

Based on the impressive activity with R2 in FL, Alliance investigators conducted 2 phase I studies of the combination of R2 plus idelalisib, one in relapsed or refractory FL, and the other in relapsed or refractory MCL.41 Prior studies in CLL suggested that rituximab could be safely combined with idelalisib.36 Both studies were terminated early after 3 MCL and 8 FL patients were accrued due to excessive, unexpected toxicity. Dose-limiting toxicities included transaminitis, septic shock, hypotension with rash, and lung infection. After these dose-limiting toxicities were noted, the protocols were amended to remove rituiximab, which appeared to be temporally related to the toxicities. Three additional patients were added: 2 developed rash leading to drug discontinuation; one developed liver chemistry abnormalities; and one had pulmonary infiltrates.41 Similarly, Cheah et al42 reported a series of 7 patients with relapsed indolent NHL treated with R2 + idelalisib. None had hepatic disease or involvement by lymphoma prior to treatment; notably, 3 who subsequently developed liver chemistry abnormalities were receiving statins. Of the first 4 patients, all developed grade 2 to 4 alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevations within the first 2 to 3 weeks of concurrent therapy, resulting in lenalidomide dose interruption. Four patients also experienced a bilirubin elevation, including one grade 4. Treatment was discontinued until the abnormalities resolved. Two patients who remained on only rituximab and idelalisib subsequently developed grade 3 ALT elevations. Two deaths were noted on study: one due to hepatic failure and one due to respiratory failure. Both patients had experienced severe infectious complications. The authors speculated that lenalidomide provided T-cell costimulation, suppressed regulatory T-cell expansion, and enhanced Th1 cytokine production, whereas the idelalisib impacted both the regulatory and the effector arms of the immune system, leading to both immune suppression and autoimmunity.

Discussion

We are in a remarkable era of advancement in novel strategies for the treatment of patients with a broad spectrum of B-cell malignancies. New monoclonal antibodies and ADCs targeting the cell surface, inhibitors of various intracellular pathways, and others that impact the microenvironment (eg, lenalidomide and check point inhibitors) have greatly expanded our treatment repertoire. In general, these agents are well tolerated, certainly with a more favorable toxicity profile than standard chemoimmunotherapeutic regimens. As these targeted drugs primarily induce partial remissions, and may require indefinite administration, numerous doublets and triplets are in development to increase efficacy and, perhaps, to limit the duration of therapy.

Unfortunately, a number of combinations have been precluded by unexpected toxicities, and more are expected. The mechanisms behind these effects remain unknown, but may be elucidated by preclinical studies. Pneumonitis has previously been demonstrated with mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors in 2% to 39% of patients.43,44 A consequence of PI3K and spleen tyrosine kinase inhibition by drugs such as idelalisib and entospletinib is to inhibit the downstream mTOR pathway. Burke et al39 noted a synergistic decrease in cell viability and a greater decrease in S6 phosphorylation in peripheral blood and bone marrow samples from CLL patients when entospletinib and idelalisib were combined compared with either agent alone, consistent with increased mTOR inhibition. Barr et al40 identified a number of cytokines/chemokines related to immune cell recruitment and T helper 1–type responses, as well as inflammation and pneumonitis (including interferon-γ, interleukin-7 [IL]-7, IL-6, and IL-8) in serum samples of patients who developed pneumonitis, compared with the patient group who did not. In contrast, these elevations had not been noted in the previous single-agent study in which IL-7 levels actually decreased after 8 weeks of therapy. Cheah et al42 noted a spike in T-cell activation markers in their patients who developed transaminitis.

Further supporting the contribution of immune stimulation are the reports of enhanced toxicity in untreated patients who have received idelalisib. Lampson et al45 described their findings in 24 patients with treatment-naïve CLL who received idelalisib in combination with ofatumumab. Fifty-seven percent of patients, all less than 65 years old, experienced grade 3 or worse transaminitis at a median time of onset of 28 days. Liver biopsy revealed a lymphocytic infiltration, requiring immunosuppression for management. Reintroduction of therapy was unsuccessful as patients experienced a rapid recurrence in transaminitis. Further investigation revealed a decrease of regulatory T cells while patients received idelalisib. Similarly, O’Brien et al reported a 64% incidence of diarrhea/colitis in previously untreated patients 65 years of age or older who received the drug with rituximab.46 Intestinal biopsies from patients with idelalisib-related colitis showed intraepithelial CD8+ lymphocytosis and crypt cell apoptosis.47,48

Patients who receive idelalisib often experience toxicities that appear to be immune mediated, which may be related, at least in part, by a defect in the number and function of CD4 T-regulatory cells.49 These observations, and primarily the increased risk of opportunistic infection, notably Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia and cytomegalovirus, have led to the termination of several combination trials with idelalisib, most notably in previously untreated patients, including those combined with well-tolerated chemotherapy regimens such as bendamustine and rituximab, and even rituximab alone (Gilead Sciences, letter to investigators, March 14, 2016). It should be stressed, however, that such findings have been variably reported with other PI3K inhibitors. Flinn et al50 reported 32 patients with relapsed and refractory indolent NHL treated with the PI3K-δ/PI3K-γ inhibitor duvelisib. Grade 3 or worse increases in ALT/aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were recorded in 41% of patients, with diarrhea in 22%. In T-cell NHL, Horwitz et al51 noted grade 3 or worse increases in AST/ALT in 36%. In a study of the pan-class I PI3K inhibitor copanlisib in indolent NHL, there were no grade 3 or worse episodes of pulmonary toxicity, AST/ALT elevations, or diarrhea reported.52 In contrast, in the mantle cell subset of this study,53 there was a fatality from drug-related respiratory failure. Thus, although correlative mechanistic data from these studies are not publically available, these observations are sufficient to suggest that some of these toxicities may represent a class effect. The excess toxicity with idelalisib that has not been reported with other PI3K inhibitors may reflect, in part, the relatively less clinical experience and shorter follow-up with the newer agents, and the greater use of anti-infectious prophylaxis, not administered with idelalisib. Nonetheless, TGR-1202, a next-generation PI3K-δ inhibitor, is quite active and appears to have less toxicity than others of this class.54 In vitro data suggest that TGR-1202 acts differently from other PI3K inhibitors with relatively greater retention of immune checkpoint blockade, suggesting relative preservation of number and function of regulatory T cells.55

The bcl-2 inhibitor venetoclax has recently received FDA approval for the second-line treatment of CLL patients with 17p deletion.56 This highly active agent has also demonstrated activity in patients with NHL. However, in early studies, 2 treatment-related deaths from tumor lysis resulted in a modification of the schedule of the administration, which can be administered safely.57 However, cautious observation must be exercised when combining it with other active agents.

Arguably one of the most exciting new classes of drugs in oncology, checkpoint inhibitors, capitalizes on the concept of immune stimulation by engaging cytotoxic T-cell activity for antitumor effect. Programmed death (PD)-1 receptor antibodies, pembrolizumab and nivolumab, have already been approved in melanoma and non–small cell lung cancer generally with acceptable toxicity.58,59 However, the resulting enhanced effector cell function may be associated with severe immune-related toxicities, including pneumonitis, colitis, hepatitis, nephritis, and thyroid dysfunction, often requiring further immunosuppression.60 Recently, immune checkpoint inhibitors have demonstrated considerable activity in various lymphomas.61-63 In a report on 23 heavily pretreated patients with HL who received nivolumab, the ORR was 87%, with few grade 3 and no grade 4 or 5 toxicities reported.61 Nivolumab in 79 patients with NHL resulted in 15 (18%) patients with grade 3, 2 patients with grade 4, and one patient with fatal toxicity (acute respiratory distress syndrome). Discontinuation of drug was required in 2 of 8 patients who experienced pneumonitis. Twenty-eight (34%) patients experienced an immune- mediated AE, possibly attributed to enhancement of immune response with T-cell activation and proliferation. These toxicities were predominantly grade 1 or 2, and, in 46%, the immune-mediated AE resolved without treatment or interruption of nivolumab. Of 15 patients who required treatment of immune-mediated AEs, only 5 discontinued nivolumab. Immune-mediated AEs resolved spontaneously or following protocol-specified treatment in 82% of patients.63 Data with pembrolizumab in HL also suggest that it is effective and safe with 10% pneumonitis, few grade 3 AEs, and no treatment-related grade 4 toxicities or deaths.63 However, colitis and elevations in AST and ALT were reported in individual patients. Westin et al64 reported no grade 3 or worse toxicities with the combination of pidilizumab and rituximab in relapsed FL. However, data from combination studies with other agents, including those that target BTK and PI3K, are as yet unavailable and will be of interest. Because of concerns of the potential for reactivation of graft-versus-host disease, prior allogeneic stem cell transplant patients had been excluded from studies of PD-1 inhibitors. Nonetheless, anecdotal data suggest that this approach may be safe.65

An ever-increasing number of potential therapeutic targets are being identified, driving the development of combination of multiple agents. Others of potential interest include tazemetostat, an enhancer of zeste-homolog 2 inhibitor,66 and selinexor, a selective inhibitor of nuclear export.67 Both demonstrated activity with modest toxicity. Of concern was grade 3 transaminase elevations with the former agent, and severe anorexia with the latter, which may impact potential combinations.

In addition, second- and third-generation versions of previously established successes are under investigation.68 For example, ibrutinib-associated toxicities appear to occur with less frequency with the second-generation acalabrutinib, perhaps related to the fact that the latter does not appear to inhibit EGFR signaling, which may be associated with rash and diarrhea; ITK signaling, which modulates natural killer cell function; or TEC kinase, which is expressed on platelets.68

The number of possible doublets and triplets is daunting. For example, if there were only 8 drugs plus one anti-CD20 antibody available, the possible number of combinations of doublets would be 36, with 84 triplets. The number of permutations of doublets would be 72, with 504 triplets. Not only do these opportunities provide optimism that better therapeutic strategies will be identified but also there is an associated risk that unexpected toxicities will be encountered.

Thus, how to best select agents for multitargeted regimens presents a challenge. Combinations should be based on sound scientific rationale. However, major obstacles in study design are the lack of available biomarkers or relevant preclinical models, often resulting in empiric choices. Because multiple drugs are directed at similar targets (eg, PI3K, BTK, PD-1), combinations should include the agents with the most favorable single-agent activity and safety profile, and with no mechanistic or clinically apparent reason for additive toxicity. To expedite study conduct, novel statistical designs should be considered, such as a closely monitored, multiarm, adaptive randomized trial strategy, rapidly dropping less effective regimens, and adding newer ones for testing. Unfortunately, the development of combinations of agents is often constrained by the drugs made available by the various pharmaceutical companies.

The question arises as to whether to abandon regimens which, while active, are associated with prohibitive toxicity. Alterations in dose or schedule, additional supportive measures, or the incorporation of drug holidays for drugs with prolonged administration may ameliorate adverse effects, permitting further development of active programs. One example is lenalidomide, which is now more often administered for 21 days of a 28-day cycle, because continuous administration was too toxic. Another is the stepped-up dosing now used with venetoclax to minimize the likelihood of tumor lysis syndrome.57

As clinical research moves quickly to a chemotherapy-free approach in many histologies of lymphoma and more targeted drugs become commercially available, there will be a temptation to arbitrarily combine them in general practice. However, it is imperative that such combinations be carefully monitored in clinical trials before subjecting patients to a risk of serious, unforeseen complications.

Authorship

Contribution: B.D.C. developed the concept for the manuscript and wrote it in its entirety.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.D.C. received consulting fees from Gilead Sciences Inc., Pharmacyclics, Celgene, Roche-Genentech, AbbVie, and Astellas, and research funding to his institution from Pharmacyclics, Teva, Celgene, AbbVie, Gilead Sciences Inc., and Acerta Pharma.

Correspondence: Bruce D. Cheson, Georgetown University Hospital, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Washington, DC 20007; e-mail: bdc4@georgetown.edu.