Abstract

Introduction:

Since the first description of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) mobilization over forty years ago, it has become the standard of care for both autologous and allogeneic transplantation. A five-day course of G-CSF represents the most commonly used mobilization regimen today. The CXCR4 inhibitor, plerixafor, is a more rapid but weak mobilizer when used as a single agent, thus emphasizing the need for faster acting agents with more predictable mobilization responses and fewer side effects.

Methods:

Given the critical role of VLA4/VCAM1 signaling for migration and retention of HSPC, we were seeking to identify small molecule antagonists of VLA4 with improved potency and bioavailability. Relative to previously described comparators Bio5192 (▢4▢1-specific) and firategrast (▢4▢1 and ▢4▢7 dual-specific), our lead candidate, CWHM-823, exhibited increased aqueous solubility and ~10-100 fold better activity in blocking VLA4 and mobilizing HSPC in mice. CWHM-823 pharmacokinetics and mobilization were assessed in BALB/c and DBA/2 mice at different doses (3 to 15 mg/kg) and time points (15 to 240 min) when administered alone or in combination with the truncated isoform of the CXCR2 agonist Gro-beta (tGro-β, 2.5 mg/kg, generously provided by GlaxoSmithKline). HSPC mobilization was monitored using flow cytometry and clonogenic in vitro assays. "True" stem cells were measured in a serial competitive transplantation assay. The combination of tGro-β and VLA4 antagonist was further tested in diabetic mice in comparison to G-CSF (9 x 100μg/kg, q12h). RNA profiling of flow-sorted HSPC was performed via microarray analysis.

Results:

The combination of tGro-β with each VLA4 antagonist resulted in a dramatic synergistic increase in circulating HSPC numbers when compared to steady state (50-70-fold) or treatment with single agents (3-10 fold) including tGroβ. Mobilization with tGro-β + CWHM-823 was rapid, peaking at 15-30 minutes after injection. In a model of streptozotocin-induced diabetes, the mobilopathy (reduction in stem cell mobilization compared to wild type mice) was considerably less pronounced with the combination tGro-β + CWHM-823 (~1.5-fold lower CFU mobilization in diabetic mice) versus the 5-day course of G-CSF (~3-fold reduction).

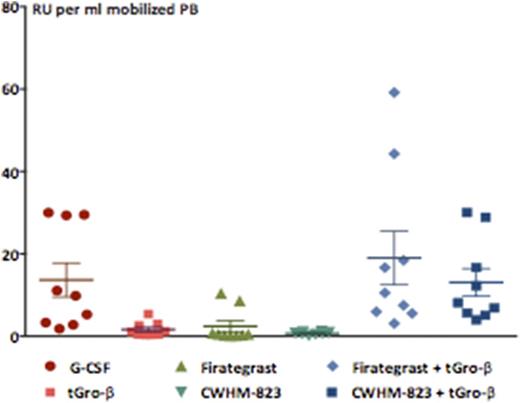

Despite the superior progenitor cell mobilization achieved with G-CSF (~2-fold more CFU and LSK/ml), the concentration of serially repopulating units (RU) was equally high in the tGro-β + CWHM-823 and G-CSF mobilized grafts suggesting a higher HSC frequency (1 RU out of 200 vs. 1 RU out of 400 LSK/CFU) in the tGro-β + CWHM-823 mobilized grafts (Figure 1). RNA profiling demonstrated close similarity between the expression profile of tGro-β + CWHM-823 mobilized, BM resident, and G-CSF mobilized LSK, with less than 0.5% of genes found to be significantly up- or downregulated.

CXCR2 chemokine receptor stimulation was critical for the observed synergistic response, as pretreatment ("priming") or simultaneous treatment with tGro-β resulted in subsequent enhanced mobilization using VLA4 inhibitors, whereas reversed administration (VLA4 antagonist followed by tGro-β) had no effect on potency of either agent. Lack of surface CXCR2 expression on HSPC suggested that a rapidly acting effector molecule released from tGro-β-stimulated mature myeloid cells may subsequently influence VLA4-mediated HSPC adhesion/retention. Consistent with this theory, we observed increased protease MMP-9 in plasma within minutes after treatment with tGro-β + CWHM-823.

Conclusions:

We describe a novel strategy for rapid, reliable, and potent mobilization of HSPC in mice using a combination of VLA4 blockade (via novel and potent ▢4▢1 inhibitors) and CXCR2 activation (via tGro-β). The combination of tGro-β + VLA4 inhibitors or tGro-β followed by VLA4 inhibitors results in synergistic and rapid HSPC mobilization with quantity and quality of repopulating units similar to optimal mobilization with G-CSF. These data suggest further development of tGro-β + VLA4 inhibitor combinations for clinical testing is warranted.

Mobilization of repopulating units (RU) (n=8-10 recipients per group, mean±SEM)

Mobilization of repopulating units (RU) (n=8-10 recipients per group, mean±SEM)

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal