Abstract

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) that develops from pre-existing hematologic diseases, rather than developing de novo, is known as secondary AML (sAML). A number of hematologic malignancies can progress to sAML. However, the molecular and genetic characteristics behind the progression of hematologic malignancies to sAML remain unclear. To address this question and dissect the order of mutation acquisition throughout the course of the disease, we performed whole-exome sequencing and targeted deep sequencing on serial samples.

Patients and Methods

This study examined several cohorts with a combined total of 124 patients. This study was approved by research ethics boards at relevant institutions and samples were taken after informed consent. The discovery cohort (C1) consisted of 31 patients diagnosed with myelodysplasia who all progressed to sAML. Whole-exome sequencing (WXS) was performed for each case on bone marrow samples taken at the diagnosis of the antecedent malignancy and after sAML progression, as well as fractionated T-cell samples (CD3+). WXS (Agilent SureSelect v4) was performed on the 93 samples as per the manufacturer's protocol using an Illumina HiSeq 2000. The other cohorts included 72 non-progressed MDS patients (C2a, median follow-up of 3.5 years) and an additional 21 sAML patients (C2b) progressed to sAML from MDS, for whom samples from the MDS stage were not available. Targeted sequencing was performed using an Agilent custom probe set of the selected 92 genes. We multiplexed and sequenced the samples using an Illumina Hiseq 2000. Targeted deep sequencing was performed on all cohorts. Genomon-ITD was used to detect FLT3-ITD.

Results

The mean read depth retrieved for target regions for WXS data was 73x. After calling and prioritizing variants, we found a mean and median of 7.7 and 6 significant variants per patient at the time of initial diagnosis, and 12.4 and 10 variants after sAML progression, respectively. We also detected that FLT3-ITD emerged in 2 patients after sAML progression.

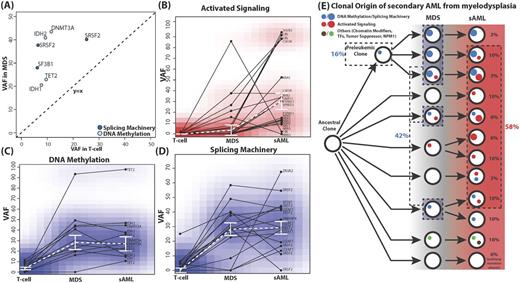

The presence of variants in T-cell samples in 5 C1 and 20 C2a patients provides evidence on the relative timing of early events for a subset of patients. Both cohorts notably lack activated signaling pathway variants at this stage (Figure A). The T-cell variants in 5 C1 patients with pathway associations were all in genes involved in DNA methylation (DNMT3A, IDH1/2, and TET2) or splicing machinery (SRSF2 and SF3B1). This pattern was verified in 20 C2a patients except for a single case that had an NRAS-G13D mutation. These patients showed evidence of having clonal hematopoiesis.

At MDS, there were a significant number of cases with variants in genes involved in DNA methylation and/or splicing machinery (35.5% and 48.3%, respectively). However, the portion of cases with variants affecting these pathways increased significantly at the MDS stage, but did not change much by the sAML stage (Figure C-D). On the other hand, variants in genes involved in activated signaling pathways showed a distinctive pattern. The portion of cases with variants affecting activated signaling pathways noticeably increased at the sAML step (25.8% to 54.8%) (Figure B). The changes in VAF between stages within cases of these variants revealed a similar pattern.

In summary, clonal evolution patterns can be postulated based on the acquisition/expansion of mutations related to the three signature pathways (Figure E). Forty-eight percent of patients showed growth or development of clones containing activated signaling pathway variants at the sAML stage. Sixteen percent of patients developed the MDS from preleukemic mutations associated with DNA methylation or splicing machinery, and 26% first developed clones of this category at the MDS stage (a total of 42%).

Conclusion

Mutations in DNA methylation and splicing machinery genes are early disease events, expanding at the MDS stage but not during progression. On the other hand, activated signaling pathway mutations expand during progression, demonstrating that distinct categories of genetic lesions play roles at different stages of sAML in a generally fixed order.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal