Key Points

Addition of lenalidomide to R-B is highly active in patients with untreated MCL, but associated with unexpected high rates of infections and SPMs.

Abstract

For elderly patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), there is no defined standard therapy. In this multicenter, open-label phase 1/2 trial, we evaluated the addition of lenalidomide (LEN) to rituximab-bendamustine (R-B) as first-line treatment for elderly patients with MCL. Patients >65 years with untreated MCL, stages II-IV were eligible for inclusion. Primary end points were maximally tolerable dose (MTD) of LEN and progression-free survival (PFS). Patients received 6 cycles every four weeks of L-B-R (L D1-14, B 90 mg/m2 IV, days 1-2 and R 375 mg/m2 IV, day 1) followed by single LEN (days 1-21, every four weeks, cycles 7-13). Fifty-one patients (median age 71 years) were enrolled from 2009 to 2013. In phase 1, the MTD of LEN was defined as 10 mg in cycles 2 through 6, and omitted in cycle 1. After 6 cycles, the complete remission rate (CRR) was 64%, and 36% were MRD negative. At a median follow-up time of 31 months, median PFS was 42 months and 3-year overall survival was 73%. Infection was the most common nonhematologic grade 3 to 5 event and occurred in 21 (42%) patients. Opportunistic infections occurred in 3 patients: 2 Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and 1 cytomegalovirus retinitis. Second primary malignancies (SPM) were observed in 8 patients (16%). LEN could safely be combined with R-B when added from the second cycle in patients with MCL, and was associated with a high rate of CR and molecular remission. However, we observed a high degree of severe infections and an unexpected high number of SPMs, which may limit its use. This trial is registered at www.Clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00963534.

Introduction

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is associated with poor prognosis, with a reported median overall survival (OS) of 5 years.1 The MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI), which divides patients into 3 prognostic risk groups based on the parameters of age, performance status (PS), lactate dehydrogenase level, and white blood cell count, was proposed in 2008 and has been validated retrospectively as well as in a prospective randomized study.2-5

Survival rates of MCL have improved during the last decade, mainly because of the addition of rituximab (R) and, for the young patient population, frontline intensive treatment including cytarabine.1,6-9 However, for the older patients, who constitute the majority of the MCL population, there is no defined standard therapy. For this group, R-CHOP followed by rituximab maintenance was associated with prolonged survival compared with R-FC.10 The German STiL group compared R-bendamustine (R-B) and R-CHOP in a randomized trial and concluded that R-B was associated with higher PFS and less toxicity, making this regimen preferable.11,12 Lenalidomide (LEN), an immunomodulating agent, has shown activity in relapsed/refractory MCL as well as in first line therapy.13-15

Consequently, the Nordic Lymphoma Group designed a trial to investigate efficacy and safety of LEN in combination with R-B as first-line treatment of patients >65 years with MCL.

Methods

This multicenter, open-label, nonrandomized phase 1/2 study was carried out in 19 centers in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland. The study was performed in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki and subsequent updates until 2008, and was conducted according to the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, issued by The International Conference on Harmonization (ICH). The protocol was approved by all national Ethical Review Boards. All patients signed a written informed consent. The study was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT00963534.

Study design/objectives

The primary end points were in the phase 1 part to determine the maximally tolerable dose (MTD) for LEN in combination with R-B, and in the phase 2 expansion cohort, progression-free survival (PFS). Secondary end points included overall response rate (ORR), complete remission rate (CRR) with and without positron emission tomography (PET), molecular remission rate measured by polymerase chain reaction, OS, and safety.

Treatment

The regimen consisted of an induction phase with 6 cycles of LBR (LEN [by mouth, days 1-14], bendamustine [90 mg/m2 IV, days 1-2], rituximab [375 mg/m2 IV, day 1]), cycle duration 28 days, followed by a maintenance phase with single-agent LEN (by mouth, days 1-21), cycle duration 28 days, up to a maximum of 7 cycles (total duration 52 weeks).

In phase 1, the treatment plan followed a sequential dose escalation according to a 3+3 design. The initial dose of LEN in cycles 1 to 6 was 5 mg, escalated by 5 mg in each step. In cycles 7 to 13, the dose of LEN was 25 mg.

Dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) was defined as any grade 3 to 5 nonhematologic adverse event (AE) within the first 2 cycles of LBR, with the exception of thromboembolic events grade 3 to 4, nonpersisting nausea, diarrhea, elevated transaminases, or events attributed to progressive disease. A recovery to absolute neutrophil count ≥1.0 × 109/L and platelet count ≥100 × 109/L was required before the next cycle was started.

Initially, the protocol included premedication with corticosteroids before rituximab infusion exclusively in cycle 1, but after protocol amendment (discussed later), corticosteroids were administered before every rituximab infusion, and in cycle 2, all patients received oral prednisone 20 mg days 1 to 14, followed by 1 week tapering of the dose. The use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was mandatory in cycles 1 to 6, because the addition of LEN was expected to augment hematologic toxicity.

Antibiotic prophylaxis was not initially recommended. After the first case of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), co-trimoxazole was prescribed to all patients.

All patients received allopurinol 300 mg per day by mouth, days 1 to 3 in cycle 1, but not thereafter because of the risk of cutaneous reactions in combination with bendamustine.

Thrombosis prophylaxis was recommended to all patients during the treatment phase, unless contraindicated (aspirin 75 mg/day, or low-molecular-weight heparin to patients with a history of a thromboembolic event and/or a known hypercoagulable state).

Eligibility criteria

Patients were eligible if they were >65 years or ≤65 years but unable to tolerate high-dose chemotherapy, with a confirmed diagnosis of MCL stage II to IV and World Health Organization Performance status 0-3, requiring treatment as a result of at least one of the following symptoms: bulky disease, nodal or extra nodal mass >7 cm, B– symptoms, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase, involvement of ≥3 nodal sites (each with a diameter >3 cm), symptomatic splenic enlargement, compressive syndrome, or pleural/peritoneal effusion. Further, patients should not have received any previous treatment (1 cycle of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy was accepted).

Assessment during study

At baseline, all patients underwent clinical examination, collection of blood samples, bone marrow (BM) biopsies and aspirates, and computed tomography (CT) of the neck, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis. BM and peripheral blood (PB) samples were sent for MRD analyses and a formalin-fixed tissue sample was collected for central review. During treatment, patients were assessed with clinical examination before each cycle and blood samples were obtained at days 1, 7, 14, and 21, respectively.

Response evaluation was performed after 3 and 6 cycles of LBR, as well as 6 weeks (1.5 months) after completion of therapy, and included CT and BM examination including samples for MRD assessment. PET scan was recommended (not mandatory) at baseline, and after 6 and 12 months. Patients were subsequently assessed with clinical examination, labs, and CT scan every 6 months until 36 months after end of treatment.

Response was evaluated according to the International Response Criteria of 2007.16,17 Toxicity was evaluated according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 3.0 (NCI CTCAE).

Detection of MRD was performed as previously described.8 Briefly, DNA was extracted, sequenced, and used as a template for patient-specific primer design and standard nested polymerase chain reaction amplification of clonally rearranged immunoglobulin heavy-chain (IGHV) genes and/or Bcl-1/IGHV rearrangement (translocation 11;14).

Statistical methods

A prolongation of PFS of 6 months compared with the reported median PFS of 30 months (at time of protocol design) in the R-B arm in the German STiL group trial was considered significant.11 Based on exponentially distributed PFS, a 95% confidence interval was calculated to 23.1 months by 40 observations, the reason the total sample size was determined as 60 patients with 20 patients in phase 1 and 40 patients in phase 2.

Progression-free survival was defined as the interval between registration date and date of documented progression, lack of response, first relapse, or death of any cause. Overall survival was defined as time from registration to death from any cause. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival curves for PFS and OS. Comparison of frequency of adverse events in different groups was based on χ2 tests. Analysis on the incidence of infection in relation to lymphocyte subpopulations was conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test. For statistical analyses, SPSS v.22 was used. All analyses were based on data collected through February 27, 2015.

Results

Fifty-one patients were enrolled between October 12, 2009 and May 22, 2013, from 13 centers in 4 Nordic countries. The accrual was slower than expected and enrollment was stopped prematurely. One patient was excluded because of screen failure and was removed from all analyses. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Characteristic . | . |

|---|---|

| Age median, (range) | 71 (62-84) |

| Male/female | 37/13 (73/27) |

| MIPI risk group, n (%) | |

| Low | 5 (10) |

| Intermediate | 19 (38) |

| High | 26 (52) |

| Extra nodal sites (n) | |

| 0 | 9 |

| 1 | 24 |

| 2 | 10 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 |

| Missing data | 2 |

| Prior treatment (1 cycle), n (%) | 4 (8) |

| 1 R-CHOP | 2 (4) |

| 1 R-Bendamustine | 1 (2) |

| 1 R-ARA-C | 1 (2) |

| WHO performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 25 (50) |

| 1 | 22 (44) |

| 2 | 3 (6) |

| Ann Arbor stage, n (%) | |

| II | 2 (4) |

| III | 4 (8) |

| IV | 44 (88) |

| Median leukocyte count, (n × 10 9/mm3) | 8.4 (1.7-135.9) |

| Characteristic . | . |

|---|---|

| Age median, (range) | 71 (62-84) |

| Male/female | 37/13 (73/27) |

| MIPI risk group, n (%) | |

| Low | 5 (10) |

| Intermediate | 19 (38) |

| High | 26 (52) |

| Extra nodal sites (n) | |

| 0 | 9 |

| 1 | 24 |

| 2 | 10 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 |

| Missing data | 2 |

| Prior treatment (1 cycle), n (%) | 4 (8) |

| 1 R-CHOP | 2 (4) |

| 1 R-Bendamustine | 1 (2) |

| 1 R-ARA-C | 1 (2) |

| WHO performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 25 (50) |

| 1 | 22 (44) |

| 2 | 3 (6) |

| Ann Arbor stage, n (%) | |

| II | 2 (4) |

| III | 4 (8) |

| IV | 44 (88) |

| Median leukocyte count, (n × 10 9/mm3) | 8.4 (1.7-135.9) |

MIPI, Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index.

Treatment

Among all patients in phase 1+2, 37 patients (74%) completed the induction (cycles 1-6) and 12 patients (24%) completed the maintenance phase (cycles 1-13). Thirty-six patients (68%) received the established MTD dose of LEN 10 mg in combination with R-B. In summary, all 50 patients received 266 cycles of L-B-R and 28 patients received 131 cycles of single LEN. The causes for treatment discontinuation were, in descending order: toxicity (n = 28 [74%], 15 during the induction phase); progressive disease (n = 6 [16%], 5 during the induction phase); second primary malignancies (n = 3 [8%]); and consent withdrawn (n = 1). Among those who stopped treatment as a result of toxicity, 2 patients received treatment outside the study with rituximab maintenance and R-B, respectively. For CONSORT diagram of phase 1+2, see supplemental Figure 1 (available on the Blood Web site).

Safety

Phase 1.

Dose escalation and AEs including DLT are showed in supplemental Table 1. The starting dose of LEN in cohort 1 (n = 3) was 5 mg. AE grade 3 or 4 occurred in 2 patients within the first 2 cycles. One patient had infection and 1 patient had cerebral infarction after cycle 1 and allergic reaction after cycle 2, reported as related to rituximab. These events were not considered related to study treatment by the data monitor committee and the next 3 patients (cohort 2) received the escalated dose of 10 mg. In cohort 2, AE grade 3 occurred in 2 patients: 1 patient developed allergic reaction and infection and 1 with rash and infection, none assessed as DLT. In cohort 3, one patient was reported with DLT, urticaria grade 3, and sensory neuropathy with edema and hypotension, and the cohort was expanded to include another 3 patients. Among these, 1 patient developed hypotension grade 3, also regarded as DLT. Further, 1 patient had urticaria grade 3 and received a lower dose of LEN in the following cycle.

As described, a high number of AEs were observed in the first 3 cohorts, including high rate of allergic and cutaneous reactions, predominantly in the first cycle. Combined with DLT in cohort 3 at 15 mg, the protocol was amended to exclude LEN from cycle 1. Further, to exclude a dose-dependent impact of bendamustine, the amended protocol included a de-escalation schedule of bendamustine (B) for the 3 following cohorts (“A-C”) B 90 mg/m2 + LEN 10 mg (cohort A, n = 6), B 70 mg/m2 + LEN 10 mg (cohort B, n = 6), and B 70 mg/m2 + 5 mg (cohort C, n = 4), respectively. Because of hematologic toxicity, the protocol amendment also included a reduction of the dose of LEN in the maintenance part: 10 mg in the first 2 cycles after induction (cycles 7-8), and 15 mg in cycles 9 to 13. All patients received corticosteroids and PCP prophylaxis after protocol amendment.

In these 3 cohorts (A-C) of 16 patients, grade 3 AEs occurred in 3 patients during cycle 1: rash (1), pneumonia (1), and tumor lysis syndrome (1), of which the pneumonia was recorded as DLT. After cycle 2, 4 patients were reported with DLT: 3 with rash (and mucositis grade 3 in 1 patient) and 1 with sepsis grade 4. Two patients had other AEs grade 3: 1 acute coronary syndrome and 1 infection grade 3.

At this point, the assessment was made that by excluding LEN from cycle 1 and by adding corticosteroids during the L-B-R cycles, LEN could be combined with R-B and a dose reduction of bendamustine did not affect the incidence of DLT. MTD of LEN was determined to be 10 mg, given in cycles 2 to 6 in combination with bendamustine 90 mg/m2 and rituximab 375 mg/m2. The dose of LEN during maintenance was 10 mg in cycles 7 to 8 followed by 15 mg in cycles 9 to 13.

Adverse events.

The AEs, including those previously described in the phase 1 part of the study, are summarized in Table 2. In total, 29 grade 3 to 5 infections were reported in 21 (42%) patients. The infections occurred during the induction phase in 19 patients and during the maintenance phase in 2 patients. Opportunistic infections were diagnosed in 3 patients: 1 case of fatal PCP caused acute respiratory distress syndrome during induction and 1 PCP after cycle 13, as well as 1 case of cytomegalovirus retinitis.

Summary of adverse events in phase 1+2, reported as number of patients, the highest grade per patient

| . | G1 . | G2 . | G3 . | G4 . | G5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematologic | |||||

| Anemia | 29 | 14 | 2 | 1 | |

| Neutropenia | 4 | 11 | 27 | ||

| Thrombocytopenia | 15 | 8 | 9 | 1 | |

| Nonhematologic | |||||

| Infection | 2 | 6 | 13 | 6 | 2 |

| Cutaneous | |||||

| Rash | 10 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Immune system disorders | |||||

| Allergic reaction | 1 | 6 | 6 | ||

| Cytokine release syndrome | 1 | ||||

| Gastrointestinal | |||||

| Abdominal pain | 1 | ||||

| Abdominal distention | 1 | ||||

| Constipation | 3 | 4 | |||

| Diarrhea | 5 | 2 | |||

| Hemorrhoids/rectal bleeding | 4 | ||||

| Mucositis/esophagitis | 2 | 7 | 3 | ||

| Nausea/vomiting | 9 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Respiratory tract | |||||

| Cough | 1 | ||||

| Dyspnea | 2 | 1 | |||

| Cardiac | |||||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 1 | ||||

| Arrhythmia/conduction disorder | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Neurologic/psychiatric | |||||

| Cerebral infarction | 1 | ||||

| Confusion | 1 | ||||

| Dizziness | 3 | ||||

| Dysgeusia | 1 | ||||

| Headache | 3 | ||||

| Neuropathy | 4 | 1 | |||

| Syncope | 1 | ||||

| Insomnia | 1 | ||||

| Musculoskeletal | |||||

| Gout | 1 | ||||

| Joint effusion | 1 | ||||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 4 | 5 | 3 | ||

| Hepatobiliary disorders | |||||

| Cholecystitis | 1 | ||||

| Hepatic failure | 1 | ||||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Alkaline phosphatase elevation | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Aminotransferase elevation | 2 | ||||

| γ-GT elevation | 1 | 1 | |||

| Vascular | |||||

| Flushing | 1 | ||||

| Hypotension | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Phlebitis | 2 | ||||

| Thromboembolic event | 3 | ||||

| Renal and urinary | |||||

| Creatinine elevation | 2 | ||||

| Hematuria | 2 | ||||

| Urinary tract obstruction | 1 | ||||

| Other renal and urinary symptoms | 4 | 3 | 1 | ||

| General | |||||

| Anorexia | 4 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Chills | 4 | ||||

| Edema | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Fatigue | 8 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Fever | 5 | 6 | 1 | ||

| Weight loss | 2 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Weight gain | 1 | ||||

| Hyperglycemia | 1 | ||||

| Sweating | 1 | ||||

| Visual disturbance | 1 | ||||

| Dry eyes | 1 | ||||

| Tumor lysis syndrome | 2 |

| . | G1 . | G2 . | G3 . | G4 . | G5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematologic | |||||

| Anemia | 29 | 14 | 2 | 1 | |

| Neutropenia | 4 | 11 | 27 | ||

| Thrombocytopenia | 15 | 8 | 9 | 1 | |

| Nonhematologic | |||||

| Infection | 2 | 6 | 13 | 6 | 2 |

| Cutaneous | |||||

| Rash | 10 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Immune system disorders | |||||

| Allergic reaction | 1 | 6 | 6 | ||

| Cytokine release syndrome | 1 | ||||

| Gastrointestinal | |||||

| Abdominal pain | 1 | ||||

| Abdominal distention | 1 | ||||

| Constipation | 3 | 4 | |||

| Diarrhea | 5 | 2 | |||

| Hemorrhoids/rectal bleeding | 4 | ||||

| Mucositis/esophagitis | 2 | 7 | 3 | ||

| Nausea/vomiting | 9 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Respiratory tract | |||||

| Cough | 1 | ||||

| Dyspnea | 2 | 1 | |||

| Cardiac | |||||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 1 | ||||

| Arrhythmia/conduction disorder | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Neurologic/psychiatric | |||||

| Cerebral infarction | 1 | ||||

| Confusion | 1 | ||||

| Dizziness | 3 | ||||

| Dysgeusia | 1 | ||||

| Headache | 3 | ||||

| Neuropathy | 4 | 1 | |||

| Syncope | 1 | ||||

| Insomnia | 1 | ||||

| Musculoskeletal | |||||

| Gout | 1 | ||||

| Joint effusion | 1 | ||||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 4 | 5 | 3 | ||

| Hepatobiliary disorders | |||||

| Cholecystitis | 1 | ||||

| Hepatic failure | 1 | ||||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Alkaline phosphatase elevation | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Aminotransferase elevation | 2 | ||||

| γ-GT elevation | 1 | 1 | |||

| Vascular | |||||

| Flushing | 1 | ||||

| Hypotension | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Phlebitis | 2 | ||||

| Thromboembolic event | 3 | ||||

| Renal and urinary | |||||

| Creatinine elevation | 2 | ||||

| Hematuria | 2 | ||||

| Urinary tract obstruction | 1 | ||||

| Other renal and urinary symptoms | 4 | 3 | 1 | ||

| General | |||||

| Anorexia | 4 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Chills | 4 | ||||

| Edema | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Fatigue | 8 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Fever | 5 | 6 | 1 | ||

| Weight loss | 2 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Weight gain | 1 | ||||

| Hyperglycemia | 1 | ||||

| Sweating | 1 | ||||

| Visual disturbance | 1 | ||||

| Dry eyes | 1 | ||||

| Tumor lysis syndrome | 2 |

When comparing the incidence of AEs (grades 3-5) in the first cohorts (92 cycles) with the subsequent cohorts of 37 patients where LEN was omitted from cycle 1 (299 cycles), all allergic reactions occurred in the first 3 cohorts (n = 5). Furthermore, 4 of 12 (33%) patients in the first cohorts receiving LEN in cycle 1 were reported with severe cutaneous reactions compared with 5 of 37 (14%) patients in the subsequent cohorts. Regarding other AEs, no difference could be clearly distinguished.

Nine second primary malignancies (SPMs) were found in 8 patients (16%) during follow-up, of which 7 were invasive malignancies: 1 chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, 1 Hodgkin lymphoma, 1 renal cancer, 1 squamous epithelial cancer of the skin, 1 squamous epithelial lung cancer in a heavy smoker, 1 hepatocellular carcinoma, and 1 prostate cancer. Two patients had noninvasive malignancies: 1 with basal cell carcinoma and 1 with squamous cell carcinoma in situ and basal cell carcinoma.

Deaths during study.

Twelve deaths have been reported: 6 resulting from progressive disease, 3 resulting from infection during induction (of which 1 was reported to be caused by myelosuppression), and 2 resulting from SPM (lung cancer and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia). One patient with progressive disease died without a report of the cause of death.

Response

Response data are shown in Table 3. After 6 courses of LBR, ORR was 80% based on intention to treat. Seven patients were not evaluated for the following reasons: 2 deaths, 2 patients were withdrawn from study because of toxicity, 1 patient withdrew consent, 1 patient who did not undergo CT/BM (but was in CR based on PET, not included as CR), and 1 patient who had stopped treatment after 4 cycles and was evaluated as CR, recorded at the point of 1.5 months after completed therapy. At evaluation 1.5 months after completing therapy, ORR was 64%. Complete remission/Complete remission undefined (CR/CRu) was achieved in 64% (n = 32) of all patients after 6 months of LBR and in 62% (n = 31) 1.5 months after completing therapy. PET was not mandatory in the study protocol and was only performed in a minority of patients. After induction therapy, 16 of 20 evaluable patients were in complete remission (80%) and 1.5 months after completed therapy, 7 of 8 evaluated patients were in CR (88%).

Response rates and MRD according to CT scan and bone marrow examination

| CT . | 3 mo . | 6 mo . | 1.5 mo after completed therapy . |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORR (%) | 88.0 | 80.0 | 64.0 |

| CR/CRU | 24 (48%) | 32 (64%) | 31 (62%) |

| PR | 20 | 8 | 1 |

| PD | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Not evaluated* | 5 | 7 | 10 |

| Total | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| MRD-negativity | 3 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo |

| BM | 18 (50%) | 18 (56%) | 16 (64%) |

| PB | 23 (61%) | 21 (68%) | 19 (80%) |

| Evaluated BM/PB | 36/38 | 32/31 | 25/24 |

| MRD-negativity (based on intention to treat) | 3 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo |

| BM | 18 (36%) | 18 (36%) | 16 (32%) |

| PB | 23 (46%) | 21 (42%) | 19 (38%) |

| Total | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| CT . | 3 mo . | 6 mo . | 1.5 mo after completed therapy . |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORR (%) | 88.0 | 80.0 | 64.0 |

| CR/CRU | 24 (48%) | 32 (64%) | 31 (62%) |

| PR | 20 | 8 | 1 |

| PD | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Not evaluated* | 5 | 7 | 10 |

| Total | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| MRD-negativity | 3 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo |

| BM | 18 (50%) | 18 (56%) | 16 (64%) |

| PB | 23 (61%) | 21 (68%) | 19 (80%) |

| Evaluated BM/PB | 36/38 | 32/31 | 25/24 |

| MRD-negativity (based on intention to treat) | 3 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo |

| BM | 18 (36%) | 18 (36%) | 16 (32%) |

| PB | 23 (46%) | 21 (42%) | 19 (38%) |

| Total | 50 | 50 | 50 |

CR, complete remission; CRu, complete remission undetermined; ORR, overall response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial remission.

Not evaluated: death of any cause, consent withdrawn, end of study because of something other than PD, end of treatment owing to any cause and not evaluated at this time point, not done of other cause/missing data.

MRD.

A primer for assessment of MRD could be identified in 88% (43/49) of the patients before treatment, of which 42 of 43 (97%) patients were MRD-positive in BM and/or peripheral blood (PB). At 3 months, 18 of 36 (50%) analyzed patients (36% of all patients) were MRD-negative in BM, and at 6 months, 18 of 32 (56%) analyzed patients (36% of all patients) were MRD-negative in BM. At 1.5 months after completing therapy, molecular remission was achieved in 64% (16/25) of patients in BM (32% of all patients) (Table 3).

Progression-free survival and overall survival

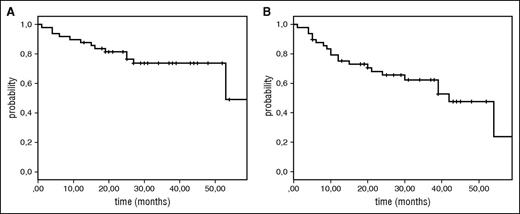

At a median follow-up time of 31 months (range, 13-59), median PFS was 42 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 31-53), median OS 53 months and 3-year OS 73% (Figure 1A-B). A separate analysis was performed on PFS and OS in relation to MIPI risk group, or age groups (≥75 years or ≥71 years, respectively) but no significant correlation could be observed. In the MIPI low-risk group, all 4 patients were alive (supplemental Figure 2A-B).

Overall survival and progression-free survival of patients enrolled in NLG/MCL2 (Lena-Berit) at a median follow-up time of 31 (13-59) months. (A) Overall survival; (B) progression-free survival.

Overall survival and progression-free survival of patients enrolled in NLG/MCL2 (Lena-Berit) at a median follow-up time of 31 (13-59) months. (A) Overall survival; (B) progression-free survival.

Lymphocyte populations

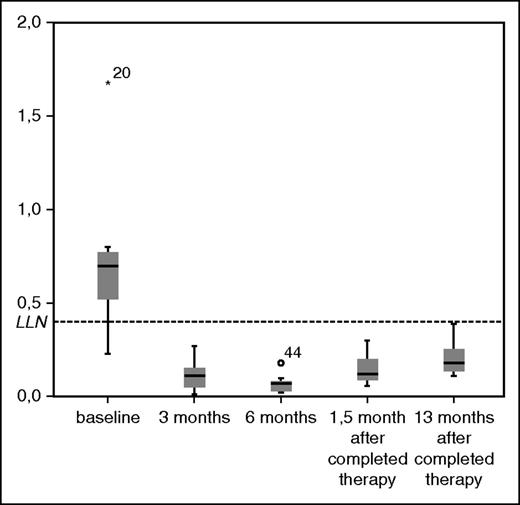

A significant decrease in median level of all lymphocyte subpopulations could be detected after 3 cycles compared with baseline levels except for CD8 (supplemental Table 2). Median values of CD4 count (109/L) was 0.6 at baseline and 0.12 after 3 months (P < .001) and remained below the lower reference limit until 13 months after completed therapy (Figure 2). Patients with any infection during treatment had significantly lower median CD4 counts at baseline (0.52 [interquartile range (IQR)] 0.34] compared with patients with no infections (0.77 [IQR 0.45] (P = .037).

Boxplots of CD4-count (109/L) during treatment. LLN, lower limit of normal range.

Boxplots of CD4-count (109/L) during treatment. LLN, lower limit of normal range.

Discussion

Although the survival for patients with MCL has improved, the disease is still considered incurable. Bendamustine in combination with rituximab has become a commonly used regimen in first line for elderly patients, on the basis of a favorable safety profile and noninferiority when compared with anthracycline-based regimens.7,12,18,19 Our results show that LEN can be combined with R-B in untreated patients when omitted in the first cycle and with the addition of corticosteroids in subsequent cycles. We identified the MTD of LEN as 10 mg for 14 days in a 28-day cycle in combination with standard doses of rituximab and bendamustine. This combination was associated with a high response rate as evaluated by CT, PET, and MRD in evaluated patients, although when based on intention to treat, the response rates are clearly lower, because a high proportion were not evaluable and/or patients were not able to complete therapy.

At a median follow-up time of 31 months, the median PFS was 42 months, which is longer than the reported PFS of 35 months in the R-B arm of MCL patients in the German STiL study according to the update published in 2013.11 In this paper, data on MIPI are not reported, but the median age of the MCL patients in the German trial was similar to our patient population. Although the difference in PFS of 7 months was the predetermined improvement that would be considered clinically significant, the 2 confidence intervals are overlapping, and consequently we cannot conclude that there is a true difference. The lower number of included patients than the precalculated sample size makes the confidence interval wider, which is why a comparison is even more difficult to make.

In our study, CR/CRu was achieved in 64% after the induction phase and in 62% after maintenance with LEN, which is higher than the 50% CRR in the MCL subgroup of the R-B arm in the BRIGHT trial, although the latter included PET as part of the response evaluation,18 but was inferior to the CRR of 74% achieved after 6 cycles of R-B plus bortezomib (RiBVD) in untreated patients with similar patient characteristics as in our study population, as well as to the CRR of 93% to 95%, observed with R-B in combination with cytarabine (R-BAC) in the subgroup of untreated MCL patients after 4 to 6 cycles.20-22

Molecular remission (MR) after combined immunochemotherapy has been defined as an independent prognostic marker for long-term remission in MCL and is associated with higher PFS in younger patients.23,24 Our data show that 36% of evaluated patients were MRD- negative in BM after induction with LBR, suggesting that molecular remission can be achieved with this regimen. However, the MR rate in BM is lower than what has been demonstrated in elderly untreated MCL patients after R-FC/R-CHOP (67%) and with RiBVD (74%).22,24 R-B followed by R-high dose cytarabine in young patients showed an even higher MRD negativity already after 3 courses of R-B (77%) and almost complete negativity (97%) after R-B+R-Ara-C, although, mainly because of a different age distribution, this study population was associated with a significantly more favorable prognostic profile, with 70% low-risk MIPI patients.25 Together, these results indicate that the addition of LEN to R-B does not increase the MR rate more than has been showed with established immunochemotherapy combinations including alkylating agents, nucleoside analogs, and anthracyclines.

In the phase 1 portion of this trial, we observed an unexpectedly high degree of severe AEs, of which almost half were allergic or cutaneous reactions. By omitting LEN from cycle 1 and by adding corticosteroids in cycle 2, the allergic reactions observed in the first cohorts could be prevented and the risk of severe cutaneous reactions was diminished, although not completely eradicated.

A major concern is the high incidence of grade 3 to 5 infections (42%), which caused treatment discontinuation in 5 (10%) patients. A similar rate of infection grade 3 to 4 was observed in the SAKK trial combining LBR.26 The incidence of severe infections is higher in our study than what has been reported with R-B alone as well as with other combinations such as RiBVD and R-BAC, which demonstrated grade 3 to 4 infections in 16% and 12% of patients, respectively.18,20,22,27

Recently, results from a trial on L-R in first line to MCL patients were published by Ruan et al. This regimen was associated with a lower number of high-grade AEs, including 13% grade 3 to 4 infections in combination with high response rate with a reported CRR of 61% and superior median PFS and OS not reached at 30 months. Notably, the median age of patients in our study was higher (71 vs 65) with more high-risk MIPI patients (52% vs 32%) and fewer patients with low-risk score (10% vs 34%).15

Rash is a common side effect of both bendamustine and LEN.11-16,28 R-B was associated with a higher degree of cutaneous toxicity when compared with R-CHOP or R-CVP.12,18,29,30 Concerning front-line LEN + rituximab in MCL, Ruan et al reported grade 3 to 4 rash in 29% of patients, in contrast to <10% in relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma.15,29,31 In line with our results, this indicates that fewer treated patients may be more susceptible to the immunosensitizing effect of LEN, perhaps because of a more intact immune system, and that corticosteroids may be required to prevent severe reactions.

Low CD4 counts after primary treatment with R-B have previously been described.32 Here, we demonstrate that the L-B-R regimen induces a longstanding reduction of CD4 counts, which persists not only during the maintenance phase of single LEN but up to 1 year after completed treatment. Together with the incidence of opportunistic infections in 3 patients, of which 1 case of PCP occurred after 13 cycles, PCP prophylaxis is warranted when combining these agents. Possibly, the addition of prednisone during the induction may have contributed to the high incidence of opportunistic infections.

During the follow-up period, SPMs were recorded in 8 (16%) patients. A higher risk of developing SPM has previously been observed after treatment with LEN.33 Studies on LEN/D in untreated MCL patients have reported SPMs in 5% of the patients and studies on L-R-CHOP in first-line have recorded SPMs around 5%.34,35 These studies included somewhat younger patients at a median age of 56, 65, and 69 years, respectively, the reason age-adjusted incidence would be valuable for comparison.

In summary, the NLG/MCL4 trial shows that LEN in combination with R-B is an active regimen in untreated elderly patients with MCL and MR may be achieved but is associated with an unfavorable safety profile including a high infection rate as well as a notably high incidence of second primary malignancies. Despite the fact that all components are highly active in MCL, LEN may not be the optimal partner of R-B in untreated patients in favor of other combinations, including cytarabine or bortezomib. It is likely that the increased toxicity associated with LEN addition outweighs a possible benefit in efficacy. In this regard, nonchemotherapy combinations including LEN and rituximab, seem to be associated with a more favorable balance of activity and toxicity, and may also be given as a maintenance treatment after chemoimmunotherapy. Long-term data on these patients as well as results from ongoing trials on chemotherapy-free combinations and randomized trials will bring further insight on how to improve outcome in elderly patients with MCL.

The study has been presented in part at the 3th International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma (ICML) in Lugano, Switzerland, June 2015.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families, all investigators, coordinators, nurses, and collaborators at the following participating centers: Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark; University Hospital of Arhus, Aarhus, Denmark; Helsinki University Central Hospital, Helsinki, Finland; Radiumhospitalet, Oslo, Norway; Stavanger Hospital, Stavanger, Norway; Gothenburg University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden; Linköping University Hospital, Linköping, Sweden; Sunderby Hospital, Luleå, Sweden; Skåne University Hospital, Lund, Sweden; Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden; Sundsvall Hospital, Sundsvall, Sweden; Norrland University Hospital, Umeå, Sweden; and Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden. The authors especially thank Sofie Medin for calculations on lymphocyte populations.

Celgene, Mundipharma and Roche provided financial support and free bendamustine and lenalidomide within the trial. Research funding to the institution was provided by Janssen-Cilag, Celgene and Mundipharma.

Authorship

Contribution: A.A.-L. collected and assembled data and wrote manuscript draft; A.K., A.L., R.R., C.G., and M.J. conceived the design and collected and assembled data; and K.G., J.S., L.B.P., E.R., M.-L.K.-L., C.S., and M.E. collected and assembled data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.J. received honoraria from Janssen-Cilag and Celgene and played a consulting and advisory role for Gilead Sciences. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alexandra Albertsson-Lindblad Department of Oncology Skane University Hospital, SE-221 85 Lund, Sweden; e-mail: alexandra.albertsson_lindblad@med.lu.se.