Abstract

We performed a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) vs no LMWH in women with inherited thrombophilia and prior late (≥10 weeks) or recurrent early (<10 weeks) pregnancy loss. Eight trials and 483 patients met our inclusion criteria. There was no significant difference in livebirth rates with the use of LMWH compared with no LMWH (relative risk, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.55-1.19; P = .28), suggesting no benefit of LMWH in preventing recurrent pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 34-year-old woman with 3 consecutive unexplained miscarriages wants to get pregnant again. Would she benefit from thrombophilia testing?

Case 2

A 25-year-old woman with 1 unexplained pregnancy loss at 16 weeks’ gestation is found to be heterozygote for the factor V Leiden mutation. She has no personal history of thrombosis. She asks whether taking low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) could prevent a second pregnancy loss.

Introduction

Recurrent pregnancy loss, commonly defined as 3 or more consecutive miscarriages, occurs in 1% of all women, with no cause identified in half of cases.1,2 Inherited and acquired thrombophilias have been evaluated as a potential cause of pregnancy loss, given the importance of adequate uteroplacental circulation on fetal development and survival. Coagulation activation at the maternal-fetal interface plays an important role in placental development.3 Several meta-analyses have reported an increased risk of pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia; however, significant heterogeneity attributed to study design and the definition of recurrent pregnancy loss limits firm conclusions.4-7 Overall, inherited thrombophilias appear to be, at best, a weak contributor to late or recurrent early pregnancy loss. Our meta-analysis evaluating only prospective cohort studies reported a small increased risk of pregnancy loss in women with factor V Leiden (FVL) (4.2%) compared with women without FVL (3.2%), suggesting a weak causal effect (odds ratio, 1.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.06-2.19).8 There is a lack of data on pregnancy loss risk in women with uncommon thrombophilias such as protein C, protein S, or antithrombin deficiency.

When compared with inherited thrombophilias, antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) has been more strongly and consistently associated with pregnancy loss; clinical criteria needed to make a diagnosis of APS include pregnancy morbidity involving either 1 pregnancy loss at ≥10 weeks’ gestation, 3 unexplained losses at <10 weeks’ gestation, or other placental complications.9-11 High-quality data to support the use of prophylactic-dose LMWH and aspirin to prevent pregnancy loss or placental complications in APS are surprisingly limited, warranting further randomized trials.12 For the purpose of this review, we will focus on inherited thrombophilia and the role of LMWH in preventing future pregnancy loss.

In women with an inherited thrombophilia and prior late or recurrent early pregnancy loss, we sought to determine whether the use of prophylactic-dose LMWH (with or without aspirin) reduced the risk of pregnancy loss when compared with no LMWH (with or without aspirin).

Methods

Study selection

A systematic search of the literature was conducted on MEDLINE (1946 to September 2015), EMBASE (1947 to September 2015), and EBM reviews using the Cochrane Database of Systematic Review (2005 to September 2015), ACP Journal Club (1981 to September 2015), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (second quarter of 2015), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (July 2015), Cochrane Methodology Register (third quarter of 2012), Health Technology Assessment (third quarter of 2015), and National Health Service Economic Evaluation (second quarter of 2015) using an OVID interface. References of narrative reviews and included trials were reviewed for additional studies, and www.clinicaltrials.gov was searched for completed and ongoing studies. The last search was completed on September 6, 2015. There was no restriction on language or date of publication. The systematic search strategy is available in supplemental Appendix 1, available on the Blood Web site. The meta-analysis was registered at the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews as #CRD42015025697.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two investigators independently reviewed all abstracts and the full text of potentially relevant studies (L.S. and M.C.). Studies were included if they met eligibility criteria outlined as follows: (1) peer-reviewed randomized controlled trial, (2) pregnant women with inherited thrombophilia and prior late (≥10 weeks) or recurrent early (≥2 losses <10 weeks) pregnancy loss, (3) randomly allocated to prophylactic-dose LMWH with or without aspirin vs no LMWH with or without aspirin, and (4) primary outcome of livebirth rate was reported. Only patients with an inherited thrombophilia were included; women with a diagnosis of APS or women who did not have a thrombophilic disorder were excluded. Secondary outcomes of adverse events such as major and nonmajor bleeding, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, increased liver enzymes, skin or allergic reactions, induction of labor, and cesarean section rates were recorded when available.13,14

Of the eligible studies, data were extracted independently by 2 investigators utilizing a standardized pilot data extraction form (L.S. and M.C.). The data extracted included number of eligible participants, study-level inclusion and exclusion criteria, intervention details, and reported outcomes. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus and were reviewed by a third investigator (M.A.R.). Individual study investigators were contacted to provide data clarifications (M.A.R., R.K., I.M., D.P., E.S., and C.A.L.), previous correspondence from P. Clark provided additional data,15 and 2 of the included studies provided all of the required details in the published manuscript.16,17 Two additional authors did not respond to queries; hence, their studies were excluded after full-text review, because the thrombophilia status or primary outcome was unknown.18,19 Study quality was independently evaluated by 2 investigators utilizing the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool (L.S. and M.C.).20

Outcomes were analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Relative risks (RRs) using a random effects model were reported with 95% CIs. The I2 statistic was used to estimate total variation among the pooled estimates across trials. An I2 <25% was considered low-level heterogeneity. A sensitivity analysis excluding single-center trials was completed. A priori exploratory analyses were planned to evaluate LMWH prophylaxis in subgroups of 2 vs ≥3 early pregnancy losses, and in prior early (<10 weeks) or late (≥10 weeks) loss. Analyses were performed using StatsDirect software version 2.8.0 (Cheshire, United Kingdom).

Our treatment recommendations are based on the quality of available evidence and are outlined using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation tool.21

Results

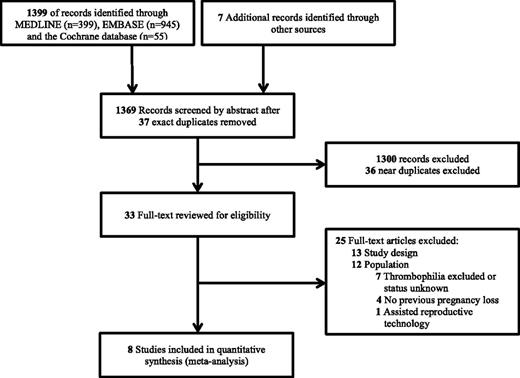

Our search strategy identified 1406 article records, of which 8 publications and 483 participants met eligibility criteria (Figure 1).15-17,22-26 Baseline study characteristics are depicted in Table 1. Of the 8 publications included, 4 trials included an LMWH-plus-aspirin arm, and 5 trials included an LMWH-only arm. The control groups included 4 trials with an aspirin arm, and 5 trials with a placebo or no-treatment arm. One of the trials that compared LMWH vs no LMWH allowed aspirin use in either arm.25 The definition of pregnancy loss varied across each trial. Study quality is reported in Table 2. Every trial that was included had adequate random sequence generation, good allocation concealment, and no selective reporting, and most trials (6/8) clearly addressed incomplete outcome data. All trials used open-label LMWH; however, the outcome of livebirth rate is objective and therefore unlikely to increase the risk of bias. Only 2 of the 8 trials reported blinding of outcome assessors.24,25

Study characteristics

| No. of patients . | Mean gestational age at entry, wk . | Thrombophilia included . | Inclusion criteria for pregnancy loss . | Treatment arm 1 . | Treatment arm 2 . | Treatment arm 3 . | Trial (year) . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 160 | 8.0* | FVL, PGM, PS | 1 loss ≥10 wk | Enoxaparin 40 mg | ASA 100 mg | N/A | Gris et al (2004) | 16 |

| 19 | 5.7 | FVL, PGM, PC, PS, MTHRF | 2 losses <32 wk | Dalteparin 5000 IU + ASA 81 mg | ASA 81 mg | N/A | HepASA (2009) | 22 |

| 47 | 6.0* | FVL, PGM, PC, PS, AT | 2 losses ≤20 wk | Nadroparin 2850 IU + ASA 80 mg | ASA 80 mg† | Placebo | ALIFE (2010) | 17 |

| 10 | 6.0‡ | FVL, PGM, PC, PS, AT | 2 losses ≤24 wk | Enoxaparin 40 mg + ASA 75 mg | No treatment | N/A | SPIN (2010) | 15 |

| 26 | 5.2 | FVL, PGM, PC, PS | 3 losses <13 wk, 2 losses 13-24 wk, 1 loss >24 wk + 1 loss <13 wk | Enoxaparin 40 mg + ASA 100 mg | Enoxaparin 40 mg + placebo | ASA 100 mg | HABENOX (2011) | 23 |

| 23 | 11.0 | FVL, PGM, PC, PS, AT | 1 loss >15 wk | Nadroparin 3800 IU | No treatment | N/A | HAPPY (2012) | 24 |

| 143 | 11.9 | FVL, PGM, PC, PS, AT | 3 losses <10 wk, 2 losses 10-16 wk, 1 loss ≥16 wk | Dalteparin 5000 IU§ (ASA allowed) | No treatment (ASA allowed) | N/A | TIPPS (2014) | 25 |

| 55 | 7.0 | FVL, PGM, PC, PS, AT | 2 losses <12 wk, 1 loss ≥12 wk | Dalteparin 5000 IU | No treatment | N/A | ETHIG II (2015) | 26 |

| No. of patients . | Mean gestational age at entry, wk . | Thrombophilia included . | Inclusion criteria for pregnancy loss . | Treatment arm 1 . | Treatment arm 2 . | Treatment arm 3 . | Trial (year) . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 160 | 8.0* | FVL, PGM, PS | 1 loss ≥10 wk | Enoxaparin 40 mg | ASA 100 mg | N/A | Gris et al (2004) | 16 |

| 19 | 5.7 | FVL, PGM, PC, PS, MTHRF | 2 losses <32 wk | Dalteparin 5000 IU + ASA 81 mg | ASA 81 mg | N/A | HepASA (2009) | 22 |

| 47 | 6.0* | FVL, PGM, PC, PS, AT | 2 losses ≤20 wk | Nadroparin 2850 IU + ASA 80 mg | ASA 80 mg† | Placebo | ALIFE (2010) | 17 |

| 10 | 6.0‡ | FVL, PGM, PC, PS, AT | 2 losses ≤24 wk | Enoxaparin 40 mg + ASA 75 mg | No treatment | N/A | SPIN (2010) | 15 |

| 26 | 5.2 | FVL, PGM, PC, PS | 3 losses <13 wk, 2 losses 13-24 wk, 1 loss >24 wk + 1 loss <13 wk | Enoxaparin 40 mg + ASA 100 mg | Enoxaparin 40 mg + placebo | ASA 100 mg | HABENOX (2011) | 23 |

| 23 | 11.0 | FVL, PGM, PC, PS, AT | 1 loss >15 wk | Nadroparin 3800 IU | No treatment | N/A | HAPPY (2012) | 24 |

| 143 | 11.9 | FVL, PGM, PC, PS, AT | 3 losses <10 wk, 2 losses 10-16 wk, 1 loss ≥16 wk | Dalteparin 5000 IU§ (ASA allowed) | No treatment (ASA allowed) | N/A | TIPPS (2014) | 25 |

| 55 | 7.0 | FVL, PGM, PC, PS, AT | 2 losses <12 wk, 1 loss ≥12 wk | Dalteparin 5000 IU | No treatment | N/A | ETHIG II (2015) | 26 |

ASA, aspirin; AT, antithrombin deficiency; MTHRF, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; N/A, not applicable; PC, protein C deficiency; PGM, prothrombin gene mutation; PS, protein S deficiency.

Gestational age when LMWH was initiated.

Calcium carbasalate 100 mg daily is equivalent to aspirin 80 mg daily.

Gestational age at study entry reported as median.

Dalteparin 5000 IU dosed once daily until 20 wk, and then twice daily until at least 37 wk gestation.

Quality assessment of included studies

| Reference . | Random sequence generation . | Allocation concealment . | Blinding of participant/personnel . | Blinding of outcome assessors . | Incomplete outcome data . | Selective reporting . | Other bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | + | + | + | ? | ? | + | + |

| 22 | + | + | + | ? | ? | + | + |

| 17 | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| 15 | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| 23 | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| 24 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 25 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 26 | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Reference . | Random sequence generation . | Allocation concealment . | Blinding of participant/personnel . | Blinding of outcome assessors . | Incomplete outcome data . | Selective reporting . | Other bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | + | + | + | ? | ? | + | + |

| 22 | + | + | + | ? | ? | + | + |

| 17 | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| 15 | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| 23 | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| 24 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 25 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 26 | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

+, Low risk of bias; ?, unclear risk of bias.

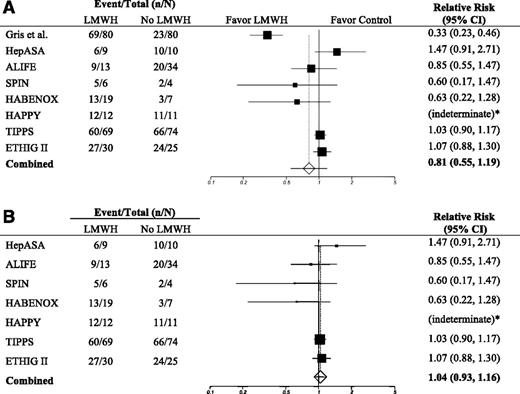

In our primary outcome analysis, there was no significant difference in livebirth rates with the use of LMWH when compared with no LMWH (RR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.55-1.19; P = .28; I2, 91.9%).15-17,22-26 Given the high heterogeneity, we performed a sensitivity analysis to explore multicenter vs single-center trials as a cause of heterogeneity. When evaluating multicenter trials, there was no difference in livebirth rates between groups, with reduced heterogeneity (RR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.93-1.16; P = .52; I2, 12.9%) (Figure 2, Table 3).15,17,22-26

Forest plot of the relative risk of pregnancy loss comparing LMWH vs no LMWH. (A) All trials are included. (B) Multicenter trials only are included. “Favor LMWH” suggests a benefit of LMWH in preventing pregnancy loss; “Favor Control” suggests a benefit of no LMWH in preventing pregnancy loss; * denotes an indeterminate RR because there were no pregnancy losses among the 23 women from the HAPPY trial.24

Forest plot of the relative risk of pregnancy loss comparing LMWH vs no LMWH. (A) All trials are included. (B) Multicenter trials only are included. “Favor LMWH” suggests a benefit of LMWH in preventing pregnancy loss; “Favor Control” suggests a benefit of no LMWH in preventing pregnancy loss; * denotes an indeterminate RR because there were no pregnancy losses among the 23 women from the HAPPY trial.24

Results of a meta-analysis of eligible trials comparing LMWH vs no LMWH in preventing future pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia

| . | Proportion with outcome in the treatment group . | Proportion with outcome in the control group . | RR . | 95% CI . | P . | I2, % . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % . | n/N . | % . | n/N . | |||||

| Primary outcome | ||||||||

| Livebirth rate | 84.5 | 201/238 | 64.9 | 159/245* | 0.81 | 0.55-1.19 | .28 | 91.9 |

| Livebirth rate (multicenter trials) | 83.5 | 132/158 | 82.4 | 136/165* | 1.04 | 0.93-1.16 | .52 | 12.9 |

| Prior late loss† | ||||||||

| Livebirth rate | 84.2 | 128/152 | 59.0 | 92/156 | 0.81 | 0.38-1.72 | .58 | 95.3 |

| Livebirth rate (multicenter trials) | 81.9 | 59/72 | 90.8 | 69/76 | 1.12 | 0.97-1.30 | .13 | 0.0 |

| Prior recurrent early loss‡ | ||||||||

| Livebirth rate§ | 86.5 | 32/37 | 86.2 | 25/29 | 0.97 | 0.80-1.19 | .79 | N/A |

| . | Proportion with outcome in the treatment group . | Proportion with outcome in the control group . | RR . | 95% CI . | P . | I2, % . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % . | n/N . | % . | n/N . | |||||

| Primary outcome | ||||||||

| Livebirth rate | 84.5 | 201/238 | 64.9 | 159/245* | 0.81 | 0.55-1.19 | .28 | 91.9 |

| Livebirth rate (multicenter trials) | 83.5 | 132/158 | 82.4 | 136/165* | 1.04 | 0.93-1.16 | .52 | 12.9 |

| Prior late loss† | ||||||||

| Livebirth rate | 84.2 | 128/152 | 59.0 | 92/156 | 0.81 | 0.38-1.72 | .58 | 95.3 |

| Livebirth rate (multicenter trials) | 81.9 | 59/72 | 90.8 | 69/76 | 1.12 | 0.97-1.30 | .13 | 0.0 |

| Prior recurrent early loss‡ | ||||||||

| Livebirth rate§ | 86.5 | 32/37 | 86.2 | 25/29 | 0.97 | 0.80-1.19 | .79 | N/A |

N/A, not applicable; n/N, number (n) with outcome/number (N) in treatment group.

One participant in the control group (aspirin alone) had a twin pregnancy with 1 livebirth and 1 stillbirth.

Late loss is defined as 1 loss ≥10 wk.

Recurrent early loss is defined as 2 losses <10 wk.

All trials included were multicenter trials.

When evaluating outcomes in the subgroup of 308 women with inherited thrombophilia and late (≥10 weeks) pregnancy loss in 5 trials, there was no significant difference in livebirth rates between the LMWH and the control group (RR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.38-1.72; P = .58; I2, 95.3%).16,23-26 Again, given the high heterogeneity in this subgroup analysis, we performed a multicenter vs single-center sensitivity analysis. When only multicenter trials were analyzed, there was no significant difference between the LMWH vs no-LMWH groups (RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.97-1.30; P = .13), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) (Table 3).23-26

When evaluating early recurrent pregnancy loss (≥2 losses <10 weeks) in 2 trials, there was no significant difference in livebirth rates between the LMWH group and the control group in 66 participants with inherited thrombophilia (RR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.80-1.19; P = .79) (Table 3).25,26

Safety outcomes were not uniformly reported for our population of interest; all adverse events reported have been described in the context of larger clinical trials. There were not enough data available to compare 2 vs ≥3 losses in women with thrombophilia.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, prophylactic-dose LMWH (with or without aspirin) did not reduce the risk of pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia with prior late or recurrent early pregnancy loss when compared with no treatment or aspirin alone. This finding was consistent across subgroups of either previous late (≥10 weeks) or previous recurrent early (<10 weeks) pregnancy loss. To our knowledge, this is the largest study published to date that evaluates LMWH in women with inherited thrombophilia and previous pregnancy loss, made possible by international collaboration with investigators who provided additional data in 6 of the 8 trials.

We did not see evidence of a beneficial effect of LMWH in preventing future pregnancy loss in thrombophilic women with prior recurrent early loss. However, given our limited sample size (n = 66), we cannot exclude a beneficial effect of LMWH in this subgroup. There is an ongoing randomized controlled trial, ALIFE2 (Netherlands Trial Registration Identifier: NTR3361), that is evaluating LMWH in women with inherited thrombophilia and a history of 2 or more miscarriages and/or intrauterine fetal death, which we hope will provide definitive answers to this question.27

In the era of responsible testing and prescribing practices, the results of our meta-analysis provide further evidence that there is no benefit of LMWH in preventing future pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia, but there is the potential for adverse side effects and significant cost of LMWH.28 By extension, this finding also significantly limits the benefit of thrombophilia testing in women with pregnancy loss. If LMWH intervention is not going to be offered (outside of clinical trials), then why test? One could argue that because there is a higher prevalence of inherited thrombophilia in women with prior pregnancy loss, testing offers an opportunity to identify women with thrombophilia. However, the benefits of identifying thrombophilia would be limited to alerting these women and their health care providers to their lifetime risks of venous thrombosis with an opportunity for thromboprophylaxis during high-risk periods (including the postpartum interval). The associated cost of testing to identify 1 case would be significant, given the weak association with pregnancy loss.

There are several limitations to our meta-analysis. We included the use of aspirin in either treatment arm because we were primarily evaluating the role of LMWH vs no LMWH. We cannot exclude the possibility that a combined treatment effect of LMWH and aspirin was lost by combining results with LMWH alone, or that aspirin in the control group mitigated any differences seen between groups. Unfortunately, the number of patients included was too small to evaluate outcomes from trials that did not include aspirin in either treatment arm. It is reassuring that a recent Cochrane Review found no difference in livebirth rates in women with or without inherited thrombophilia treated with LMWH and aspirin vs no treatment (RR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.87-1.16), and no difference between aspirin vs no treatment (RR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.80-1.11).29 These results are further supported by the Effects of Aspirin in Gestation and Reproduction [EAGeR] trial, in which there was no difference in livebirth rates between aspirin and placebo in women with previous pregnancy loss.30

There were 2 trials that were excluded from our meta-analysis because we could not extract the necessary data from the published manuscripts and the authors could not be contacted. The trials were excluded because either we did not know if the patients were tested for an inherited thrombophilia18 or outcomes based on an inherited thrombophilia subgroup were not available.19 In the worst-case scenario, we missed data from 111 women with inherited thrombophilia, but it is very likely that this number is <50. It is unlikely that our study conclusions would have differed with this change in number of patients.

Because the inclusion criterion for prior pregnancy loss was different in every trial, we could only pool data from a limited number of trials to evaluate LMWH in the subgroups of prior late or recurrent early pregnancy loss. Furthermore, we could not specifically evaluate subgroups of later pregnancy loss in women with prior loss at >16 weeks’ or >24 weeks’ gestation. Standardization of a definition for early and late pregnancy loss is urgently needed across disciplines to guide future clinical trials and permit meaningful meta-analysis. The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology published a 2014 consensus statement on the research definition of pregnancy loss, recommending early pregnancy loss be defined as <10 weeks’ gestation when organogenesis is complete.31 Furthermore, the definition of recurrent pregnancy loss (ie, 2 or 3 losses) is still debated and remains undefined.31

There were also differences across trials in the types of inherited thrombophilia included and the method in which thrombophilia testing was performed. A patient-level meta-analysis could provide additional data on the outcomes for specific thrombophilias, as well as address the issue of heterogeneity in the varying definitions of pregnancy loss.

In conclusion, we found no difference in preventing future pregnancy loss with LMWH when compared with no LMWH in women with inherited thrombophilia and prior late or recurrent early pregnancy loss. Further research evaluating LMWH prophylaxis in women with thrombophilia and recurrent early pregnancy loss is still needed.

Recommendations

In women with prior late or recurrent early pregnancy loss, we suggest not testing for inherited thrombophilia over testing for inherited thrombophilia. (Grade 2B, weak recommendation with moderate-quality evidence.)

We recommend against the use of LMWH to prevent recurrent pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia and prior late pregnancy loss (≥10 weeks) over the use of LMWH. (Grade 1B, strong recommendation with moderate-quality evidence.)

We suggest against the use of LMWH to prevent recurrent pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia and prior recurrent early pregnancy loss (<10 weeks) over the use of LMWH. (Grade 2B, weak recommendation with moderate-quality evidence.)

Cases revisited

Case 1

We would advise against testing for inherited thrombophilia.

Case 2

We would not recommend the use of LMWH to prevent future pregnancy loss.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by a Thrombosis Canada CanVECTOR Research Fellowship award (L.S.); a Heart and Stroke Foundation New Investigator Award and a University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Chair in Venous Thromboembolism and Cancer (M.C.); and a Heart and Stroke Foundation Career Investigator Award (CI6225 and CI7441) and a University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Chair in Venous Thrombosis and Thrombophilia (M.A.R.).

Authorship

Contribution: L.S., M.C., and M.A.R. developed the methods for the systematic review and meta-analysis, participated in the review and selection of included publications, and participated in the data analysis; L.S. and M.C. participated in the data extraction; M.A.R. had the initial idea for the study; R.K., I.M., D.P., E.S., and C.A.L. were investigators for a component study and provided additional data; and L.S. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed drafts of the manuscript and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.C. received honoraria from Pfizer and Leo Pharma. R.K. received grant funding from Sanofi Aventis. E.S. received grant funding from Pfizer Pharma GmbH Germany. M.A.R. received grant funding from Boehringer Ingelheim and was a paid expert for the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marc A. Rodger, The Ottawa Hospital, Centre for Practice-Changing Research, 501 Smyth Rd, Box 201, Ottawa, ON, Canada K1H 8L6; e-mail: mrodger@ohri.ca.