Key Points

The complement opsonin C3dg, which is found on PNH erythrocytes of patients under anti-C5 therapy, can bind to complement receptor 3 (CR3).

Interaction of C3dg with CR3 on activated monocytes induces erythrophagocytosis, thereby corroborating a model of extravascular hemolysis.

Abstract

The clinical management of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), a rare but life-threatening hematologic disease, has fundamentally improved with the introduction of a therapeutic that prevents complement-mediated intravascular hemolysis. However, a considerable fraction of PNH patients show insufficient treatment response and remain transfusion dependent. Because the current treatment only prevents C5-induced lysis but not upstream C3 activation, it has been speculated that ongoing opsonization with C3 fragments leads to recognition and phagocytosis of PNH erythrocytes by immune cells. Here, for the first time, we provide experimental evidence for such extravascular hemolysis and demonstrate that PNH erythrocytes from anti–C5-treated patients are phagocytosed by activated monocytes in vitro. Importantly, we show that this uptake can be mediated by the end-stage opsonin C3dg, which is not traditionally considered a phagocytic marker, via interaction with complement receptor 3 (CR3). Interaction studies confirmed that C3dg itself can act as a ligand for the binding domain of CR3. The degree of C3dg-mediated erythrophagocytosis in samples from different PNH patients correlated well with the individual level of C3dg opsonization. This finding may guide future treatment options for PNH but also has potential implications for the description and management of other complement-mediated diseases.

Introduction

In paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), somatic mutations in genes responsible for glycophosphatidylinositol synthesis lead to clonal populations of blood cells lacking several membrane proteins. Absence of complement regulators CD55 and CD59 renders affected cells susceptible to complement attack. Most visibly, the formation of membrane attack complexes (MACs) on erythrocytes causes intravascular hemolysis, resulting in anemia.1 The introduction of a therapeutic antibody against complement C5 (eculizumab), which prevents MAC-mediated intravascular hemolysis, profoundly improved the clinical management of PNH.2,3 However, the hematologic benefit is heterogeneous among patients, with up to one-third showing residual anemia and remaining transfusion dependent. Importantly, eculizumab only blocks C5-mediated effector functions but not complement activation itself that is driven by C3.1 PNH erythrocytes from eculizumab-treated patients are therefore coated with C3 fragments. Although it was suggested that this perpetual opsonization might lead to extravascular hemolysis through phagocytosis,4 this hypothesis has not yet been experimentally confirmed. PNH erythrocytes still express CD35, a regulator that mediates rapid transformation of C3 opsonins into the C3dg stage (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site).5 A hypomorphic variant of CD35 has been associated with increased C3 deposition and lower chance to achieve significant hematologic benefit.6 In contrast to C3b and iC3b, however, C3dg is not generally recognized as phagocytic opsonin. However, early reports suggested that the tryptic C3d fragment of C3dg mediates binding to complement receptor 3 (CR3, CD11b/CD18) on monocytes.7 Recently, structural studies revealed that the C3d domain contains the interaction site of iC3b for CR3.8 We therefore hypothesized that C3dg may act as independent opsonin that contributes to erythrophagocytosis, thereby corroborating the mechanism of extravascular hemolysis in PNH.

Study design

Human samples

Blood was collected from PNH patients and volunteers in EDTA vacutainer tubes after venipuncture, following informed consent as approved by local institutional review boards. PNH erythrocytes were analyzed for C3 fragment deposition as previously described.9 This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Interaction analysis

The interaction of CR3-αMI with opsonins was analyzed by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) as detailed in the supplemental Methods. Briefly, C3b was deposited on a sensor chip and converted into iC3b and C3dg as described previously.10 Binding analysis was performed in Mg2+-containing buffer by injecting CR3-αMI (0.03-2 µM) over C3b, iC3b, and C3dg. To test magnesium dependence, CR3-αMI was injected in buffer containing either MgCl2 or EDTA. Interaction specificity was validated using blocking antibodies against CD11b or C3d.

Phagocytosis assay

Human peripheral monocytes were seeded on glass coverslips at 106 cells per well. After incubation (1 day), cells were maintained in medium with 10 ng/mL phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) for 4 days at 37°C and 5% CO2. Washed erythrocytes from PNH patients or volunteers were added to activated monocytes (30:1 ratio). After a 15-minute incubation, coverslips were washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and phagocytosis was terminated by lysing extracellular erythrocytes in water (30 seconds). Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline (30 minutes, ice) and permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X100 for 20 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-C3d and allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-glycophorin antibodies. Coverslips were mounted to slides with mounting medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Intracellular erythrocytes were observed under a microscope. Phagocytosis was quantified by counting the number of monocytes with internalized erythrocytes as the portion of total monocytes in random fields until the total number of cells reached 200. To confirm CR3 specificity, monocytes were incubated with 20 µg/mL anti-CD11b or anti-CD21 (negative control) for 1 hour before adding erythrocytes.

Results and discussion

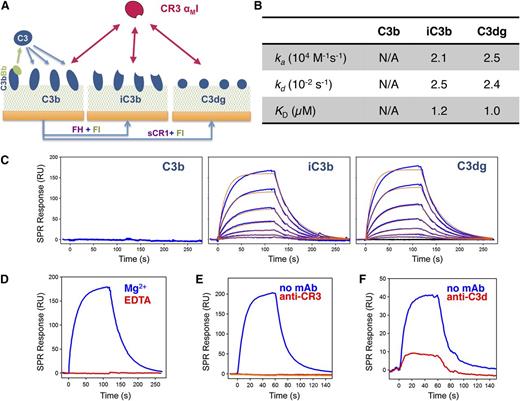

We first investigated whether C3dg, the predominant opsonin found on PNH erythrocytes during eculizumab treatment,4,9 may bind CR3. This receptor recognizes various ligands, including iC3b, via its αMI domain.11 We recombinantly expressed CR3-αMI (supplemental Figure 2) and confirmed opsonin specificity by SPR using opsonin surfaces (C3b, iC3b, C3dg) prepared in a close-to-physiologic manner (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 3A). As expected, CR3-αMI did not bind C3b but strongly bound iC3b (Figure 1B-C). Importantly, the interaction with C3dg followed the profile of iC3b, thereby confirming that physiologically deposited C3dg serves as ligand for CR3-αMI. As early cell-based studies were performed with C3d,7,12,13 we compared binding to C3dg and C3d but detected no significant difference (supplemental Figure 3B-D). The interaction was Mg2+ dependent (Figure 1D), supporting reports that CR3 binds the C3d domain via its metal-ion-dependent adhesion site domain.8 A monoclonal antibody (mAb) known to bind the αMI domain14 completely blocked the interaction (Figure 1E) and was used to determine receptor specificity in subsequent experiments. We also identified an anti-C3d mAb that impaired binding of CR3-αMI considerably (Figure 1F). Although avidity during cell-cell interactions may influence the binding profile, and additional contacts with CR3 may be involved in the case of iC3b,8 our study demonstrates that C3dg can act as independent binding partner for CR3.

Interaction between CR3-αMI and C3-derived opsonins in physiologic orientation. (A) Schematic overview of surface opsonization for the SPR study. C3b was covalently deposited via its thioester domain by on-chip formation of the C3 convertase and injection of C3. The resulting C3b surfaces were either left unchanged or converted to iC3b and C3dg by injecting factor I (FI) with cofactors factor H or soluble CR1, respectively (supplemental Methods; supplemental Figure 2A). (B-C) Interaction profile of CR3-αMI toward C3b, iC3b, and C3dg. Recombinant CR3-αMI (0.03-2 µM) was injected over all 3 opsonin surfaces in Mg2+-containing buffer, and the interaction was recorded as change in SPR response in resonance units (RU). In the case of iC3b and C3dg, processed responses (C; blue) were fit to a 1:1 Langmuir model (C; red) to extract kinetic rate constant and binding affinity (B); the C3b surface did not result in a significant binding response. The binding data are representative of 2 independent experiments with comparable results. (D-F) Evaluation of binding specificity of the CR3-αMI interaction with C3dg. (D) Metal ion dependence was tested by injecting CR3-αMI (500 nM) to C3dg in the presence of either 1 mM MgCl2 or 3 mM EDTA. Binding sites were validated using blocking antibodies against (E) the αMI domain of CR3 (mAb CBRM1/5) and (F) the C3d domain of C3 (mAb 1149).

Interaction between CR3-αMI and C3-derived opsonins in physiologic orientation. (A) Schematic overview of surface opsonization for the SPR study. C3b was covalently deposited via its thioester domain by on-chip formation of the C3 convertase and injection of C3. The resulting C3b surfaces were either left unchanged or converted to iC3b and C3dg by injecting factor I (FI) with cofactors factor H or soluble CR1, respectively (supplemental Methods; supplemental Figure 2A). (B-C) Interaction profile of CR3-αMI toward C3b, iC3b, and C3dg. Recombinant CR3-αMI (0.03-2 µM) was injected over all 3 opsonin surfaces in Mg2+-containing buffer, and the interaction was recorded as change in SPR response in resonance units (RU). In the case of iC3b and C3dg, processed responses (C; blue) were fit to a 1:1 Langmuir model (C; red) to extract kinetic rate constant and binding affinity (B); the C3b surface did not result in a significant binding response. The binding data are representative of 2 independent experiments with comparable results. (D-F) Evaluation of binding specificity of the CR3-αMI interaction with C3dg. (D) Metal ion dependence was tested by injecting CR3-αMI (500 nM) to C3dg in the presence of either 1 mM MgCl2 or 3 mM EDTA. Binding sites were validated using blocking antibodies against (E) the αMI domain of CR3 (mAb CBRM1/5) and (F) the C3d domain of C3 (mAb 1149).

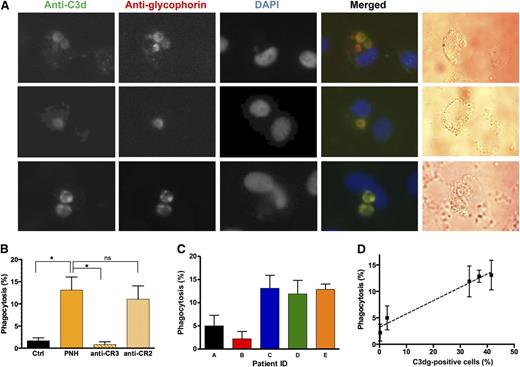

We then asked whether this interaction mediates phagocytosis of PNH erythrocytes. When erythrocytes from PNH patients, which all tested positive for C3dg but negative for C3b/iC3b (supplemental Figure 4), were incubated with activated monocytes, erythrophagocytosis could be observed in a significant fraction of monocytes (Figure 2A). The identity of the internalized structures was confirmed as C3dg-coated PNH erythrocytes by positive staining with anti-glycophorin and anti-C3d antibodies (Figure 2A). Blockage of CR3-αMI essentially stopped phagocytosis, whereas a blocking control antibody against complement receptor 2 had no obvious effect (Figure 2B). Between the samples from 5 PNH patients, the degree of erythrophagocytosis varied significantly (Figure 2C) but showed strong correlation with the percentage of C3dg-positive cells (Figure 2D). These observations support the hypothesis that C3dg acts as ligand for CR3 and as a phagocytic opsonin that may contribute to erythrophagocytosis. Previous reports about C3d binding to monocytes via CR3 have been controversially discussed.7,12,13 The activation state of the monocytes appears to be critical to allow for proper expression of activated CR37 ; indeed, erythrophagocytosis was only observed in PMA-activated adherent monocytes but not in fresh suspension monocytes (data not shown). Recently, residual phagocytosis by THP-1 macrophages was reported for rabbit erythrocytes coated with a plasmin-mediated C3dg-like opsonin.15

Phagocytosis of C3dg-coated PNH erythrocytes by activated human monocytes. (A) Visualization of intracellular erythrocytes by fluorescent microscopy. The processes of phagocytosis and immunostaining are described in Methods. PNH erythrocytes were identified by positive staining with anti-C3d and anti-glycophorin antibodies. (B) Phagocytosis quantification. The results represent the average of 3 independent experiments, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. In each phagocytosis experiment, activated human monocytes were incubated with erythrocytes from a healthy donor (Ctrl) or PNH patient E (panel C). To test whether the phagocytosis is accomplished via CR3, a CR3-specific blocking antibody was preincubated with activated monocytes before adding the PNH erythrocytes, and a blocking anti-CR2 mAb was used as a nonspecific control (n = 3; *P < .05, 1-way analysis of variance). (C-D) Correlation between phagocytosis efficiency by activated human monocytes and C3dg coating of PNH erythrocytes. Phagocytosis experiments were performed with erythrocytes from 5 different PNH patients. The data in C represent the average of 3 independent experiments with error bars indicating the standard deviation. (D) Correlation between the fraction of C3dg-positive cells (supplemental Figure 4) and erythrophagocytosis (C), with error bars indicating the standard deviation (Pearson r = 0.99; P = .002).

Phagocytosis of C3dg-coated PNH erythrocytes by activated human monocytes. (A) Visualization of intracellular erythrocytes by fluorescent microscopy. The processes of phagocytosis and immunostaining are described in Methods. PNH erythrocytes were identified by positive staining with anti-C3d and anti-glycophorin antibodies. (B) Phagocytosis quantification. The results represent the average of 3 independent experiments, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. In each phagocytosis experiment, activated human monocytes were incubated with erythrocytes from a healthy donor (Ctrl) or PNH patient E (panel C). To test whether the phagocytosis is accomplished via CR3, a CR3-specific blocking antibody was preincubated with activated monocytes before adding the PNH erythrocytes, and a blocking anti-CR2 mAb was used as a nonspecific control (n = 3; *P < .05, 1-way analysis of variance). (C-D) Correlation between phagocytosis efficiency by activated human monocytes and C3dg coating of PNH erythrocytes. Phagocytosis experiments were performed with erythrocytes from 5 different PNH patients. The data in C represent the average of 3 independent experiments with error bars indicating the standard deviation. (D) Correlation between the fraction of C3dg-positive cells (supplemental Figure 4) and erythrophagocytosis (C), with error bars indicating the standard deviation (Pearson r = 0.99; P = .002).

Whereas C3b/iC3b-mediated phagocytosis likely prevails in many conditions, PNH patients under anti-C5 treatment face unique circumstances as perpetual C3 deposition without MAC-mediated lysis leads to accumulation of densely C3dg-opsonized erythrocytes.4 High C3d densities were indeed shown to be required for CR3-mediated rosetting of activated monocytes,12 and kinetic aspects during opsonization and clearance likely play a major role. In cold-agglutinin disease, accumulation of C3dg-coated erythrocytes is also observed, but opsonin densities are typically lower due to the presence of CD55, and initial rapid phagocytic elimination of cold-agglutinin disease-type cells was attributed to C3b-mediated effects.16-18 C3dg-mediated clearance in circulation and/or organs may well be slower due to lack of binding to CD35 and CR4, yet previous studies spanning several days showed that opsonized PNH erythrocytes have a reduced half-life and accumulate in the spleen and liver.4 Our data therefore suggest that conversion of opsonins to the C3dg stage does not confer protection from phagocytic removal of diseased cells but rather marks a shift in kinetics and mechanisms. Although analyzed in the context of PNH, C3dg-induced binding to CR3 on immune cells may also play a role in other pathologies in which C3 deposition on tissue is observed (eg, transplantation, atherosclerosis, kidney diseases). While not inducing phagocytosis, C3dg coating on tissues may modulate adherence and activation of immune cells; for example, binding of iC3b to CR3 on macrophages is known to modulate interleukin-12 release, and a similar effect was recently reported for C3dg.15,19

Although the contribution of this route for the in vivo clearance of PNH erythrocytes remains to be determined, our studies show for the first time that C3dg-opsonized cells from PNH patients under anti-C5 treatment can be recognized and internalized by phagocytes, thereby corroborating a mechanism of extravascular hemolysis. This finding also supports efforts to introduce therapeutic options that target C3 as treatment of PNH.1 Indeed, engineered regulators such as TT30 and mini-FH, and derivatives of the C3 inhibitor compstatin, were shown to prevent C3 opsonization of PNH erythrocytes in addition to stopping intravascular hemolysis (supplemental Figure 5).9,10,20 Further investigation of the C3dg-CR3 interaction in phagocytosis, leukocyte activation, and immune modulation will be important to elucidate the role of the C3dg opsonin in disease and therapy.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI068730, AI030040, AI097805 (National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases), EY020633 (National Eye Institute), and GM094447 (National Institute of General Medical Sciences; to J.D.L. and/or D.R.), funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under grant 602699 (DIREKT; to J.D.L.), and a pilot grant from the Penn-Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Blood Center for Patient Care and Discovery (to D.R.).

Authorship

Contribution: Z.L., C.Q.S., A.M.R., J.D.L., and D.R. conceived the study and contributed to the discussion of the data; A.M.R. and P.R. collected and analyzed patient samples; Z.L. and C.Q.S. prepared proteins and performed the biochemical/biophysical experiments; Z.L. performed the cell-based studies with help from S.K.; Z.L., D.R., and J.D.L. wrote the manuscript; and all authors critically revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.R., C.Q.S. and J.D.L. are inventors of patents/patent applications describing complement inhibitors. J.D.L. is the founder of Amyndas Pharmaceuticals, which is developing complement inhibitors for clinical applications. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Daniel Ricklin, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, 401 Stellar Chance, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: ricklin@upenn.edu; or John D. Lambris, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, 401 Stellar Chance, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: lambris@upenn.edu.

References

Author notes

J.D.L. and D.R. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal