Key Points

The median posttransformation survival of 5 years suggests improved outcomes for transformed FL in the modern era.

Five-year progression-free and overall survival (66% and 88%) are favorable for patients with evidence of transformation at diagnosis.

Abstract

We assessed the incidence, prognostic features, and outcomes associated with transformation of follicular lymphoma (FL) among 2652 evaluable patients prospectively enrolled in the National LymphoCare Study. At a median follow-up of 6.8 years, 379/2652 (14.3%) patients transformed following the initial FL diagnosis, including 147 pathologically confirmed and 232 clinically suspected cases. Eastern Cancer Oncology Group performance status >1, extranodal sites >1, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, and B symptoms at diagnosis were associated with transformation risk. Relative to observation, patients initiating treatment at diagnosis had a reduced risk of transformation (hazard ratio [HR], 0.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.46-0.75). The risk of transformation was similar in patients treated with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone compared with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (adjusted HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.62-1.42). Maintenance rituximab was associated with reduced transformation risk (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.46-0.97). Five-year survival from diagnosis was significantly worse for patients with vs without transformation (75%, 95% CI, 70-79 vs 85%, 95% CI, 83-86). The median overall survival posttransformation was 5 years. Forty-seven patients with evidence of transformation at the time of diagnosis shared similar prognostic factors and survival rates to those without transformation. Improved outcomes for transformation in the modern era are suggested by this observational study. This trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00097565.

Introduction

Historically, follicular lymphoma (FL) that transformed to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) portended a poor prognosis for most patients, with a median overall survival (OS) of 1 to 2 years.1-5 The prognosis of transformed FL (tFL) presenting at the time of initial diagnosis is uncertain because most of the prior studies of histologic transformation (HT) excluded these patients.3,5-7 Population-based and single institution studies of FL estimate an ∼3% annual incidence of HT.3,5-9 However, the incidence and outcomes of tFL may be changing with modern therapies. An analysis of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) non-Hodgkin lymphoma outcomes database demonstrated 2- and 5-year OS rates of 68% and 49%, respectively, among 118 patients with tFL diagnosed between 2000 and 2011.10 Treatment of the indolent lymphoma prior to HT included regimens containing rituximab (70%) and/or anthracyclines (51%). A smaller subset was observed without treatment (19%). Although the NCCN study highlights current treatment patterns, it does not address whether initial treatment approaches impact the risk of HT. Some older retrospective studies report an increased risk of transformation with either watchful waiting or less intensive chemotherapy approaches, whereas others, including a randomized study, observed no difference.3,7,9,11,12

The large, prospective National LymphoCare Study (NLCS) database of more than 2700 patients, including 80% treated at nonacademic sites, provides a unique opportunity to further characterize the incidence; risk factors, including the impact of initial treatment; and outcomes of patients with tFL treated with modern therapy. Additionally, we detail the outcomes for patients with transformation at the time of initial diagnosis of FL, a subset of patients previously unreported in the current era of chemoimmunotherapy.

Methods

The NLCS is a prospective, multicenter, observational study designed to collect data on disease presentation, treatment patterns, and clinical outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed FL. There were no study-prescribed evaluations, treatments, or interventions. All patients signed informed consent before participation, and the protocol was approved by each of the participating members’ institutional review boards, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were enrolled between 2004 and 2007.

Patients with FL diagnosed within 6 months of informed consent and no prior lymphoma history were eligible for enrollment. Central pathology review was not performed, but entry of World Health Organization definitions of FL in the database was required. Grading of FL was captured; however, there was no distinction among grade 3 (ie, 3A vs 3B). Initial data collection included demographics, clinical data (stage, performance status, and number of nodal and extranodal sites), and routine labs. Serial treatment strategies, response to treatment, and events including transformation, relapse, and death were collected quarterly. For clinical trial participants (6% of study population), details of the investigational treatments were not collected, although treatment responses were captured. Patients were followed from enrollment through June 2014 or until death, withdrawal of consent, or lost to follow up. Additional study details were described previously.13

Patients were categorized as transformed (suspected or confirmed) by site investigators. Guidelines to define HT were not provided. No central review of pathology or pathology reports was performed. Response was collected quarterly on electronic case report forms, and HT was queried if progressive disease was noted. Forms included the options “no,” “suspected,” and “confirmed” HT, with confirmed cases requiring date of pathological transformation. Suspected and confirmed cases were analyzed both individually and collectively. No guidelines were provided to define clinically suspected transformation. Patients with initial suspicion of transformation with subsequent biopsy confirmation were categorized as confirmed cases for the Cox models evaluating risk of confirmed transformation. HT was more clearly defined for the group of patients with evidence of transformation at the time of diagnosis, which consisted of patients with FL and DLBCL in the same biopsy specimen.

Associations between clinical and pathological features at diagnosis including histologic grade and Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) scores and risk of transformation were evaluated using multiple variable Cox regression. The impact of initial treatment approaches, including comparisons of observation vs early treatment and the use of anthracyclines and rituximab on the risk of transformation, was evaluated using the log-rank test and by multiple variable Cox regression adjusted for baseline factors (where missing values of baseline factors were considered as a valid category in the model for all factors except extranodal sites and nodal sites where there were too few patients with missing values), including the FLIPI components14 (with age categorized as <60, 60-69, 70-79, and 80+), presence of B symptoms, extranodal sites, histologic grade, and Eastern Cancer Oncology Group (ECOG) scores.

The baseline evaluation worksheets captured the FL grade, as well as any additional histology. Patients who presented at diagnosis with evidence of FL and DLBCL in the same tissue specimen were excluded from the analyses of HT following diagnosis and analyzed separately under the category “transformation at initial diagnosis.” The initial treatment worksheet included “watch and wait” and various treatment categories (eg, single-agent rituximab, single-agent chemotherapy, and combined chemotherapy with or without rituximab). The quarterly update worksheets collected treatment initiation or subsequent treatment details. The observation and treatment cohorts were categorized based on the intended approach of the investigator at the time of study enrollment. A prespecified duration of watchful waiting was not required for the observation category. Five patients who progressed prior to treatment or decision to watch and wait were excluded from analysis.

Median time to transformation, progression-free survival (PFS), OS, and corresponding 2- to 8-year percentages were estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods. PFS and OS from transformation were calculated from the time of first recorded transformation for patients with a suspected or confirmed transformation. To compare outcomes of suspected vs confirmed cases, suspected cases that were subsequently confirmed by biopsy remained categorized as suspected.

Results

Transformation rates

The study enrolled patients from March 2004 to March 2007 at 265 sites in the United States.13 Of the 2734 evaluable patients, 2652 had FL as the sole histology and no progression prior to initial treatment strategy. Forty-seven patients with evidence of transformation at initial diagnosis and 30 with FL plus an additional lymphoma histology that was not clearly DLBCL were excluded from the primary analysis. At a median follow up of 6.8 years, 379/2652 patients (14.3%) had pathologically confirmed (n = 147; 5.5%) or clinically suspected (n = 232; 8.7%) transformation. The number of assessments, including computed tomography and positron emission tomography scans, obtained at the time of confirmed or suspected transformations were similar between the groups. Of the 232 patients with suspected transformation, 25 were subsequently confirmed. Ten of the 25 patients started a treatment between suspected and confirmed transformation, of whom 8 had confirmed transformation more than 1 year after suspected transformation. The median time from suspected to confirmed transformation was 4.4 months, with 9 cases confirmed within 1 month, 6 within 1 to 6 months, and 10 within >1 year. The overall transformation rates at 2, 4, 6, and 8 years were 6.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.1% to 7.0%), 10.9% (95% CI, 9.6% to 12.23%), 15.3% (95% CI, 13.7% to 16.8%), and 19.4% (95% CI, 17.5% to 21.3%), respectively.

Clinical and disease characteristics associated with transformation risk

Baseline characteristics of patients with suspected or confirmed transformation, transformation at the time of diagnosis, or no transformation are detailed in Table 1. Factors associated with an increased risk of suspected or confirmed transformation by multiple variable Cox regression analysis were as follows: ECOG PS >1 (hazard ratio [HR], 2.12; 95% CI, 1.27-3.55), extranodal sites >1 (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.07-1.81), elevated LDH (HR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.17-2.10), and B symptoms (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.06-1.72) at diagnosis (Table 2). When restricting the analysis to confirmed cases only, similar trends were observed, with the addition of advanced stage being associated with increased risk of confirmed transformation and age 80+ associated with decreased risk of confirmed transformation possibly because of differences in assessment for these populations.

Patient characteristics

| . | Suspected . | Confirmed . | Transformed at time of diagnosis . | No transformation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 232 . | n = 147 . | n = 47 . | n= 2273 . | |

| Extranodal sites | ||||

| ≤1 | 171 (74%) | 100 (68%) | 39 (83%) | 1801 (79%) |

| >1 | 52 (22%) | 43 (29%) | 4 (9%) | 394 (17%) |

| Not done/missing | 9 (4%) | 4 (3%) | 4 (9%) | 78 (3%) |

| Nodal sites | ||||

| ≤4 | 131 (56%) | 86 (59%) | 31 (66%) | 1463 (64%) |

| >4 | 88 (38%) | 58 (39%) | 15 (32%) | 718 (32%) |

| Not done/missing | 13 (6%) | 3 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 92 (4%) |

| Grade | ||||

| I/II | 170 (73%) | 103 (70%) | 9 (19%) | 1632 (72%) |

| III | 37 (16%) | 23 (16%) | 7 (15%) | 428 (19%) |

| Unknown/missing | 25 (11%) | 21 (14%) | 31 (66%) | 213 (9%) |

| ECOG PS | ||||

| 0-1 | 126 (54%) | 89 (61%) | 33 (70%) | 1525 (67%) |

| ≥2 | 11 (5%) | 6 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 70 (3%) |

| Not done/missing | 95 (41%) | 52 (35%) | 12 (26%) | 678 (30%) |

| Hb | ||||

| <12 g/dL | 49 (21%) | 37 (25%) | 10 (21%) | 434 (19%) |

| ≥12 g/dL | 162 (70%) | 101 (69%) | 37 (79%) | 1692 (74%) |

| Not done/missing | 21 (9%) | 9 (6%) | 0 | 147 (6%) |

| LDH | ||||

| Normal | 130 (56%) | 72 (49%) | 25 (53%) | 1393 (61%) |

| >ULN | 37 (16%) | 31 (21%) | 12 (26%) | 358 (16%) |

| Not done/missing | 65 (28%) | 44 (30%) | 10 (21%) | 522 (23%) |

| Stage | ||||

| I/II | 66 (28%) | 35 (24%) | 14 (30%) | 761 (33%) |

| III/IV | 163 (70%) | 111 (76%) | 33 (70%) | 1489 (66%) |

| Not done/missing | 3 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 23 (1%) |

| B symptoms | ||||

| No | 162 (70%) | 103 (70%) | 33 (70%) | 1716 (75%) |

| Yes | 70 (30%) | 44 (30%) | 14 (30%) | 557 (25%) |

| Age | ||||

| <60 | 91 (39%) | 62 (42%) | 18 (38%) | 1028 (45%) |

| 60-69 | 55 (24%) | 46 (31%) | 14 (30%) | 582 (26%) |

| 70-79 | 55 (24%) | 33 (22%) | 6 (13%) | 448 (20%) |

| 80+ | 31 (13%) | 6 (4%) | 9 (19%) | 215 (9%) |

| FLIPI | ||||

| 0-1 | 48 (21%) | 23 (16%) | 12 (26%) | 679 (30%) |

| 2 | 55 (24%) | 38 (26%) | 10 (21%) | 549 (24%) |

| 3-5 | 73 (31%) | 52 (35%) | 17 (36%) | 602 (26%) |

| Missing | 56 (24%) | 34 (23%) | 8 (17%) | 443 (19%) |

| . | Suspected . | Confirmed . | Transformed at time of diagnosis . | No transformation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 232 . | n = 147 . | n = 47 . | n= 2273 . | |

| Extranodal sites | ||||

| ≤1 | 171 (74%) | 100 (68%) | 39 (83%) | 1801 (79%) |

| >1 | 52 (22%) | 43 (29%) | 4 (9%) | 394 (17%) |

| Not done/missing | 9 (4%) | 4 (3%) | 4 (9%) | 78 (3%) |

| Nodal sites | ||||

| ≤4 | 131 (56%) | 86 (59%) | 31 (66%) | 1463 (64%) |

| >4 | 88 (38%) | 58 (39%) | 15 (32%) | 718 (32%) |

| Not done/missing | 13 (6%) | 3 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 92 (4%) |

| Grade | ||||

| I/II | 170 (73%) | 103 (70%) | 9 (19%) | 1632 (72%) |

| III | 37 (16%) | 23 (16%) | 7 (15%) | 428 (19%) |

| Unknown/missing | 25 (11%) | 21 (14%) | 31 (66%) | 213 (9%) |

| ECOG PS | ||||

| 0-1 | 126 (54%) | 89 (61%) | 33 (70%) | 1525 (67%) |

| ≥2 | 11 (5%) | 6 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 70 (3%) |

| Not done/missing | 95 (41%) | 52 (35%) | 12 (26%) | 678 (30%) |

| Hb | ||||

| <12 g/dL | 49 (21%) | 37 (25%) | 10 (21%) | 434 (19%) |

| ≥12 g/dL | 162 (70%) | 101 (69%) | 37 (79%) | 1692 (74%) |

| Not done/missing | 21 (9%) | 9 (6%) | 0 | 147 (6%) |

| LDH | ||||

| Normal | 130 (56%) | 72 (49%) | 25 (53%) | 1393 (61%) |

| >ULN | 37 (16%) | 31 (21%) | 12 (26%) | 358 (16%) |

| Not done/missing | 65 (28%) | 44 (30%) | 10 (21%) | 522 (23%) |

| Stage | ||||

| I/II | 66 (28%) | 35 (24%) | 14 (30%) | 761 (33%) |

| III/IV | 163 (70%) | 111 (76%) | 33 (70%) | 1489 (66%) |

| Not done/missing | 3 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 23 (1%) |

| B symptoms | ||||

| No | 162 (70%) | 103 (70%) | 33 (70%) | 1716 (75%) |

| Yes | 70 (30%) | 44 (30%) | 14 (30%) | 557 (25%) |

| Age | ||||

| <60 | 91 (39%) | 62 (42%) | 18 (38%) | 1028 (45%) |

| 60-69 | 55 (24%) | 46 (31%) | 14 (30%) | 582 (26%) |

| 70-79 | 55 (24%) | 33 (22%) | 6 (13%) | 448 (20%) |

| 80+ | 31 (13%) | 6 (4%) | 9 (19%) | 215 (9%) |

| FLIPI | ||||

| 0-1 | 48 (21%) | 23 (16%) | 12 (26%) | 679 (30%) |

| 2 | 55 (24%) | 38 (26%) | 10 (21%) | 549 (24%) |

| 3-5 | 73 (31%) | 52 (35%) | 17 (36%) | 602 (26%) |

| Missing | 56 (24%) | 34 (23%) | 8 (17%) | 443 (19%) |

Hb, hemoglobin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PS, performance status; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Prognostic features of transformation

| . | Confirmed transformation . | Confirmed/suspected transformation . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | χ2P . | HR . | 95% CI . | χ2P . | |||

| Lower . | Upper . | Lower . | Upper . | |||||

| Extranodal sites | .096 | .015 | ||||||

| ≤1 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| >1 | 1.37 | 0.95 | 1.99 | .096 | 1.39 | 1.07 | 1.81 | .015 |

| Nodal sites | .588 | .167 | ||||||

| <5 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| ≥5 | 1.10 | 0.78 | 1.55 | .588 | 1.18 | 0.93 | 1.50 | .167 |

| Grade | .175 | .502 | ||||||

| I/II | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| III | 0.94 | 0.60 | 1.49 | .801 | 1.02 | 0.75 | 1.38 | .911 |

| Unknown/missing | 1.52 | 0.96 | 2.43 | .077 | 1.23 | 0.87 | 1.72 | .242 |

| ECOG PS | .117 | <.001 | ||||||

| 0-1 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 2+ | 1.74 | 0.79 | 3.85 | .173 | 2.12 | 1.27 | 3.55 | .004 |

| Not done/missing | 1.35 | 0.97 | 1.88 | .079 | 1.62 | 1.30 | 2.03 | <.001 |

| Hb | .274 | .507 | ||||||

| ≥12 g/dL | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| <12 g/dL | 1.32 | 0.91 | 1.93 | .147 | 1.17 | 0.89 | 1.52 | .258 |

| Not done/missing | 0.84 | 0.43 | 1.68 | .626 | 0.97 | 0.63 | 1.50 | .901 |

| LDH | .002 | .003 | ||||||

| Normal | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| >ULN | 2.03 | 1.35 | 3.06 | .001 | 1.57 | 1.17 | 2.10 | .003 |

| Not done/missing | 1.55 | 1.04 | 2.30 | .031 | 1.38 | 1.05 | 1.80 | .020 |

| Stage | .025 | .216 | ||||||

| I/II | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| III/IV | 1.65 | 1.06 | 2.55 | .025 | 1.19 | 0.90 | 1.58 | .216 |

| B Symptoms | .035 | .014 | ||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 1.45 | 1.03 | 2.06 | .035 | 1.35 | 1.06 | 1.72 | .014 |

| Age | .043 | .087 | ||||||

| <60 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 60-69 | 1.32 | 0.92 | 1.89 | .134 | 1.13 | 0.88 | 1.47 | .343 |

| 70-79 | 1.37 | 0.90 | 2.07 | .141 | 1.41 | 1.06 | 1.88 | .017 |

| 80+ | 0.39 | 0.14 | 1.07 | .068 | 1.41 | 0.93 | 2.13 | .104 |

| . | Confirmed transformation . | Confirmed/suspected transformation . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | χ2P . | HR . | 95% CI . | χ2P . | |||

| Lower . | Upper . | Lower . | Upper . | |||||

| Extranodal sites | .096 | .015 | ||||||

| ≤1 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| >1 | 1.37 | 0.95 | 1.99 | .096 | 1.39 | 1.07 | 1.81 | .015 |

| Nodal sites | .588 | .167 | ||||||

| <5 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| ≥5 | 1.10 | 0.78 | 1.55 | .588 | 1.18 | 0.93 | 1.50 | .167 |

| Grade | .175 | .502 | ||||||

| I/II | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| III | 0.94 | 0.60 | 1.49 | .801 | 1.02 | 0.75 | 1.38 | .911 |

| Unknown/missing | 1.52 | 0.96 | 2.43 | .077 | 1.23 | 0.87 | 1.72 | .242 |

| ECOG PS | .117 | <.001 | ||||||

| 0-1 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 2+ | 1.74 | 0.79 | 3.85 | .173 | 2.12 | 1.27 | 3.55 | .004 |

| Not done/missing | 1.35 | 0.97 | 1.88 | .079 | 1.62 | 1.30 | 2.03 | <.001 |

| Hb | .274 | .507 | ||||||

| ≥12 g/dL | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| <12 g/dL | 1.32 | 0.91 | 1.93 | .147 | 1.17 | 0.89 | 1.52 | .258 |

| Not done/missing | 0.84 | 0.43 | 1.68 | .626 | 0.97 | 0.63 | 1.50 | .901 |

| LDH | .002 | .003 | ||||||

| Normal | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| >ULN | 2.03 | 1.35 | 3.06 | .001 | 1.57 | 1.17 | 2.10 | .003 |

| Not done/missing | 1.55 | 1.04 | 2.30 | .031 | 1.38 | 1.05 | 1.80 | .020 |

| Stage | .025 | .216 | ||||||

| I/II | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| III/IV | 1.65 | 1.06 | 2.55 | .025 | 1.19 | 0.90 | 1.58 | .216 |

| B Symptoms | .035 | .014 | ||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 1.45 | 1.03 | 2.06 | .035 | 1.35 | 1.06 | 1.72 | .014 |

| Age | .043 | .087 | ||||||

| <60 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 60-69 | 1.32 | 0.92 | 1.89 | .134 | 1.13 | 0.88 | 1.47 | .343 |

| 70-79 | 1.37 | 0.90 | 2.07 | .141 | 1.41 | 1.06 | 1.88 | .017 |

| 80+ | 0.39 | 0.14 | 1.07 | .068 | 1.41 | 0.93 | 2.13 | .104 |

Statistical analyses were performed using multivariable Cox regression adjusted for induction treatment.

Bold indicates significant findings, P < .05.

Ref, reference.

Initial treatment patterns and associated risk of transformation

At initial diagnosis of FL, 21% of patients were observed; 13% received rituximab alone; 48% were given rituximab in combination with chemotherapy; 5%, 3%, and 3% of patients received radiotherapy, combined modality therapy, or chemotherapy alone; 6% were treated on clinical trials; and 1% received other treatments. Of those treated with rituximab plus chemotherapy, 50% received rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP); 23% received rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CVP); and 17% received fludarabine-containing regimens. Eighty-seven patients (16% of observation patients) in the observation arm initiated treatment within 90 days. Initial treatment approaches were analyzed with respect to time to transformation and adjusted for age, stage, ECOG PS, B symptoms, nodal sites, LDH, histologic grade, and hemoglobin (Table 3).

Initial treatment approaches and risk of transformation

| Factor . | Patients, n (%) . | Overall confirmed transformation rate, % . | Confirmed transformation adjusted HR* (95% CIs) . | Overall confirmed or suspected transformation rate, % . | Confirmed or suspected transformation adjusted HR* (95% CIs) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed patients | 555 (21) | 7.6 | 1 | 17.8 | 1 |

| Treated patients | 2097 (79) | 6.2 | 0.57 (0.39-0.83) | 13.4 | 0.58 (0.46-0.75) |

| R-CVP | 300 (11) | 6.3 | 1 | 13.3 | 1 |

| R-CHOP | 641 (24) | 6.2 | 0.83 (0.46-1.50) | 13.3 | 0.94 (0.62-1.42) |

| Chemotherapy without rituximab | 71 (3) | 8.5 | 1 | 18.3 | 1 |

| Chemotherapy with rituximab | 1284 (48) | 6.5 | 0.82 (0.33-2.07) | 13.4 | 0.61 (0.34-1.11) |

| Observation† | 609 (23) | 4.9 | 1 | 13.0 | 1 |

| Rituximab maintenance† | 529 (20) | 4.5 | 0.87 (0.50-1.52) | 9.2 | 0.67 (0.46-0.97) |

| Factor . | Patients, n (%) . | Overall confirmed transformation rate, % . | Confirmed transformation adjusted HR* (95% CIs) . | Overall confirmed or suspected transformation rate, % . | Confirmed or suspected transformation adjusted HR* (95% CIs) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed patients | 555 (21) | 7.6 | 1 | 17.8 | 1 |

| Treated patients | 2097 (79) | 6.2 | 0.57 (0.39-0.83) | 13.4 | 0.58 (0.46-0.75) |

| R-CVP | 300 (11) | 6.3 | 1 | 13.3 | 1 |

| R-CHOP | 641 (24) | 6.2 | 0.83 (0.46-1.50) | 13.3 | 0.94 (0.62-1.42) |

| Chemotherapy without rituximab | 71 (3) | 8.5 | 1 | 18.3 | 1 |

| Chemotherapy with rituximab | 1284 (48) | 6.5 | 0.82 (0.33-2.07) | 13.4 | 0.61 (0.34-1.11) |

| Observation† | 609 (23) | 4.9 | 1 | 13.0 | 1 |

| Rituximab maintenance† | 529 (20) | 4.5 | 0.87 (0.50-1.52) | 9.2 | 0.67 (0.46-0.97) |

Adjusted for age, stage, ECOG, B symptoms, nodal sites, extranodal sites, LDH, histologic grade, and hemoglobin. Rituximab maintenance comparison additionally adjusted for frontline treatment.

Patients with at least a response of stable disease to an initial rituximab-based regimen who were followed at least 215 days after the end of induction without experiencing progressive disease or starting a subsequent therapy within this time frame were included in analysis.

Observation vs early treatment.

At a median follow-up of 6.8 years, patients initially treated (n = 2097) had an overall transformation rate of 13.4% compared with 17.8% for patients initially observed (n = 555; HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.46-0.75). Results were similar when observation patients who went on to receive treatment within 90 days were classified as initially treated. No clinical factors predicted for the risk of transformation among observation patients in multiple variable Cox regression models.

Anthracycline vs nonanthracycline regimen.

Of patients initially treated, 41% (n = 859) were treated with an anthracycline-containing regimen and had an overall transformation rate of 11.9% compared with 14.4% in the nonanthracycline (n = 1238) arm (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.52-0.91). When restricting the comparison with R-CVP vs R-CHOP, the difference was no longer statistically significant (adjusted HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.62-1.42).

Rituximab vs nonrituximab chemotherapy.

A total of 1284 patients received rituximab plus chemotherapy, and 71 received chemotherapy alone. The overall transformation rates were 13.4% and 18.3% in the rituximab and nonrituximab chemotherapy arms, respectively (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.34-1.11). The length of follow-up was similar between the 2 groups.

Observation vs rituximab maintenance.

A total of 1138 patients (609, observation; 529, rituximab maintenance) with at least a response of stable disease to an initial rituximab-based regimen who were followed for at least 215 days after the end of induction treatment without experiencing progressive disease or starting a subsequent therapy within this time frame were included in the analysis. The HR (additionally adjusted for frontline treatment) for transformation was 0.67 (95% CI, 0.46-0.97) with transformation rates of 9.2% in the rituximab arm compared with 13% in the observation arm.

Survival rates

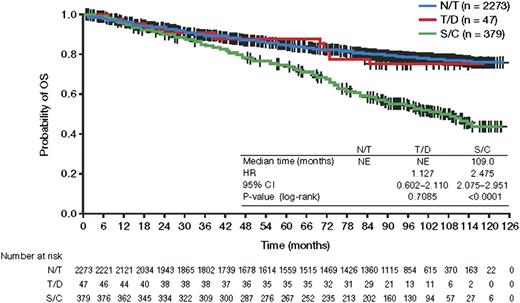

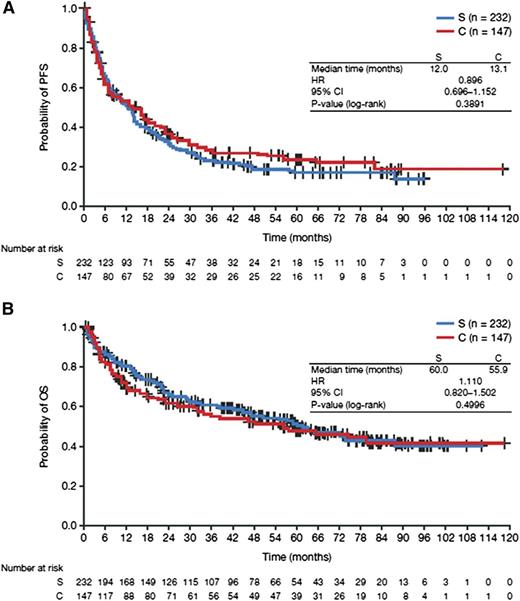

The 5-year OS rate from diagnosis was significantly worse for patients with tFL than for patients without transformation (75%, 95% CI, 70-79 vs 85%, 95% CI, 83-86; Figure 1). The median posttransformation PFS and OS were 1.0 and 4.9 years, respectively. The posttransformation PFS and OS were not significantly different between the confirmed and suspected cases (Figure 2). With respect to the initial treatment approach, a difference in posttransformation OS between the observed and treated groups was not detected (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.87-1.76). Similarly, compared with nonanthracycline-treated patients, anthracycline treatment was not associated with a significant survival difference from time of transformation (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.68-1.37), and rituximab plus chemotherapy vs chemotherapy was not associated with significant survival differences from time of transformation (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.39-1.64).

OS from time of diagnosis. NE, not evaluated; N/T, no transformation; S/C, suspected or confirmed transformation; T/D transformation at diagnosis.

OS from time of diagnosis. NE, not evaluated; N/T, no transformation; S/C, suspected or confirmed transformation; T/D transformation at diagnosis.

Posttransformation survival for confirmed and suspected transformations. (A) PFS and (B) OS. C, confirmed transformation; S, suspected transformation.

Posttransformation survival for confirmed and suspected transformations. (A) PFS and (B) OS. C, confirmed transformation; S, suspected transformation.

Transformation at initial diagnosis

Among the 2734 evaluable FL cases, 77 patients had composite histology. Forty-seven of these had documentation of FL and DLBCL. The 30 additional cases coded as FL plus a second histology were excluded because 23 cases did not specify the other lymphoma histology, 3 cases described presence of large cells but the corresponding grade was missing, 2 had chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL), 1 had marginal zone, and 1 was described as “T- cell rich” but did not specify diffuse large cell. Baseline clinical factors for the 47 patients with tFL at initial diagnosis were similar to the entire cohort (Table 1). A considerably higher percentage of patients with transformation at initial diagnosis were treated with R-CHOP compared with the entire cohort (66% vs 24%). The 5-year PFS from diagnosis was not different for patients with tFL at diagnosis and the cohort without evidence of transformation (66%, 95% CI, 50% to 79% vs 61%, 95% CI, 59% to 63%). Likewise, the 5-year OS for patients with tFL at diagnosis of 88% (95% CI, 74% to 95%) was similar to patients without evidence of transformation (Figure 1).

Treatment patterns of transformed patients

Treatment approaches following suspected or confirmed transformations were quite varied (Table 4). The majority of patients received rituximab, either as a single modality (26%) or with chemotherapy (35%). Only 2% of patients underwent bone marrow transplant.

Initial treatment following transformed lymphoma

| Treatment . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Rituximab + chemotherapy | 131 (34.6) |

| Rituximab monotherapy | 98 (25.9) |

| Radiation | 26 (6.9) |

| Chemotherapy | 25 (6.6) |

| RIT | 16 (4.2) |

| Investigational therapy | 16 (4.2) |

| Stem cell transplantation | 6 (1.8) |

| Combined modality: radiation | 5 (1.3) |

| Other noninvestigational therapy | 1 (0.3) |

| None | 55 (14.5) |

| Treatment . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Rituximab + chemotherapy | 131 (34.6) |

| Rituximab monotherapy | 98 (25.9) |

| Radiation | 26 (6.9) |

| Chemotherapy | 25 (6.6) |

| RIT | 16 (4.2) |

| Investigational therapy | 16 (4.2) |

| Stem cell transplantation | 6 (1.8) |

| Combined modality: radiation | 5 (1.3) |

| Other noninvestigational therapy | 1 (0.3) |

| None | 55 (14.5) |

RIT, radioimmunotherapy.

Discussion

Patient characteristics from the NLCS database are similar to that of the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database and therefore are likely representative of the US population.13 The NLCS database is 4.5 to 10 times larger than all previously described tFL studies, and the number of patients with transformations is nearly twice that of the largest series. In this multi-institutional, prospective, observational study, the 5- and 8-year transformation rates were 12.8% and 19.4%, respectively, which is consistent with the incidence of 9% to 17% at 5 years and 15% to 30% at 10 years observed in retrospective studies.3-7,9 The observation in other series,10,15 as well as our own, that transformation rates are similar in the modern era suggests that chemoimmunotherapy is not impacting the incidence of transformation. Our median follow-up of 6.8 years limits assessment of later transformations, and this study cannot address whether a plateau in the incidence of HT occurs at ∼15 years, which has been seen in prior studies.3,5,7,9 At 4-year follow-up, 8% of patients had either withdrawn consent or were lost to follow-up compared with 12% at 6.8 years. Given this attrition rate, later transformations may have been missed.

The gold standard for diagnosing a transformation in FL is with biopsy,16 and most of the previously published studies required pathological confirmation of transformation.1,6,7,9,17 The Vancouver population-based analysis identified 170 patients with transformation, including 107 confirmed by biopsy and 63 diagnosed clinically based on the presence of at least one of the following: LDH ≥2 times the ULN, rapid localized nodal growth, new involvement of unusual extranodal sites, new B symptoms, or hypercalcemia.3 A key finding in this study was that posttransformation survival among the 2 groups was similar (P = .2). In our series, 45% of the transformations were biopsy proven, which included 25 suspected cases that were subsequently confirmed by biopsy. Criteria leading treating investigators to suspect transformation and clinical characteristics at the time of transformation were not collected, which is a significant limitation of the study. Importantly, however, clinical characteristics at diagnosis and outcomes following transformation were similar between pathologically confirmed and clinically suspected HT, supporting the collective analysis of both groups. The NLCS did not perform central pathology review. Most prior retrospective studies did not examine tumor specimens to confirm histology, and many required reclassification of pathology reports as patients were diagnosed before the adoption of the World Health Organization classification. Given the relative accuracy in diagnosing transformed DLBCL with current pathology techniques, the lack of pathology review is not likely to be a major limitation.

Aside from a United Kingdom study that identified 5/63 (7.9%) patients with tFL at the time of diagnosis,17 the incidence and outcomes of transformation at diagnosis are not well characterized. A French study that reviewed the morphology of 782 patients with DLBCL diagnosed from 1988 to 2000 identified 60 (8%) with simultaneous evidence of a low-grade B-cell lymphoma, including 22 with FL (or 2.8% of all DLBCL cases), 32 with marginal zone lymphoma, and 6 with small lymphocytic lymphoma.18 Of the FL cases, 17 (77%) had FL and DLBCL in the same sample, whereas the remainder had evidence of FL and DLBCL in distinct locations. The 5-year freedom from progression and OS probabilities were 33% and 57%, respectively, for the entire cohort of 60 patients. Generalizations for outcomes of tFL at the time of diagnosis are somewhat limited by the inclusion of various low-grade histologies, as well as discordant lymphoma, which likely represents a different entity.19 Our study features the largest series of patients with tFL at the time of diagnosis and provides a unique opportunity to learn more about the clinical behavior of this population. Patients with tFL at diagnosis had similar clinical characteristics and outcomes (5-year OS of 88%) to those without transformation, lending support to this entity as a distinct population from those who transform following diagnosis.

With the exception of the subset of patients with tFL at diagnosis, patients with transformation had significantly worse OS compared with patients without transformation. The median posttransformation OS of nearly 5 years in the NLCS is similar to recent series of tFL.10,15 Compared with the dismal prognosis described in historical reports, these newer studies raise the question as to whether this change reflects advancements in current treatments. The disparity seen in the relatively short median posttransformation PFS of ∼1 year compared with the longer OS additionally suggests improvements in treatment. The NCCN and University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic studies did not report on PFS posttransformation. Our study did not collect data on whether subsequent recurrences posttransformation were with FL or DLBCL, although the contrasting PFS and OS curves raise the possibility that FL recurrences were more common.

The NLCS highlights important patterns of care following transformation, with a surprisingly low number of patients who underwent autologous stem cell transplant. Perhaps more remarkable is that despite these practice patterns, the outcomes look much better than the historical reports. The role of autologous stem cell transplant for tFL is certainly more controversial in the rituximab era, with recent studies highlighting worse outcomes in patients previously treated with rituximab compared with rituximab-naïve patients.20-23

There are few studies comparing initial treatment regimens and subsequent development of tFL and even fewer that are adjusted based on known clinical risk factors associated with HT. Unfortunately, none of the studies have demonstrated consistency with regard to specific regimens that may alter the risk. Additionally, none of the studies evaluate the risk with the newest regimen of bendamustine and rituximab. Our findings demonstrated no statistically significant difference in HT with rituximab; however, the nonrituximab arm was small, reflective of the use of rituximab in the modern era, which may prevent detecting a difference in risk. Interestingly, a decreased risk of transformation was seen in patients who received rituximab maintenance, and perhaps the lower transformation rate noted in those receiving early treatment compared with observed patients relates to maintenance rituximab. As the decreased risk of transformation was not borne out when comparing patients treated with R-CHOP vs R-CVP, despite an overall decreased risk of HT in the anthracycline- vs nonanthracycline-treated patients, it may be that the anthracycline is not responsible for curbing the risk. Although it is possible that anthracycline-based therapies were not observed to reduce the risk of transformation because of anthracycline administration occurring more commonly in patients with biological high-risk disease, baseline clinical risk factors were adjusted for in multiple variable Cox regression analysis. Perhaps instead, certain nonanthracycline regimens may be associated with an increased risk of transformation as has been hypothesized with purine analogs.24,25 Fludarabine constituted a small portion of the anthracycline- and nonanthracycline-containing regimens in our study, so analysis of this potential scenario was not feasible. In sum, treatment strategies cannot be recommended from this observational data, and the potential role for maintenance rituximab in reducing transformation will require careful attention to final reporting of HT rates in maturing randomized trials of maintenance rituximab.26-29

Our study’s observations are best framed in the context of 2 recent phase 3 studies, which show no OS advantage to anthracycline-based regimens, with the caveat that follow-up is still early and the prevalence of transformation is low.30,31 A relevant finding from our study was the lack of a posttransformation OS difference with up-front treatment. One of the few studies that may successfully address the role of observation vs early treatment is the Ardeshna trial, which demonstrated no difference in HT or OS among observed patients compared with those treated with rituximab at a median follow-up of nearly 4 years.28 Long-term follow-up of the comparative up-front chemoimmunotherapy trials and the Ardeshna study28,30,31 will provide important data on the risk of tFL to best inform treatment decisions.

Presented in part in abstract form at the 51st annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, New Orleans, LA, December 2009.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bokai Xia for statistical programming support.

The NLCS is funded by Genentech Inc. and Biogen Idec.

Authorship

Contribution: N.D.W.-J. and N.L.B. were responsible for study conception and design; B.K.L., J.H., C.R.F., J.W.F., and N.L.B. were responsible for provision of study materials and patients; N.D.W.-J., N.L.B., and M.B. performed collection and assembly of data; and all authors performed data analysis and interpretation, writing the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.K.L. is a member of the advisory committee and receives research funding from Genentech Inc. M.B. and K.L.D. are employees of Genentech Inc. and holds stock options with Roche/Genentech Inc. J.H., C.R.F., and J.W.F. are unpaid members of the NLCS Advisory Committee.

Correspondence: Nina D. Wagner-Johnston, 660 S Euclid, Box 8056, St. Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: nwagner@dom.wustl.edu.