Key Points

Pegylated IFNα induces hematologic and molecular remission in CALR-mutated ET patients.

The analysis of additional mutations highlights the presence of subclones with variable evolutions during IFNα therapy.

Abstract

Myeloproliferative neoplasms are clonal disorders characterized by the presence of several gene mutations associated with particular hematologic parameters, clinical evolution, and prognosis. Few therapeutic options are available, among which interferon α (IFNα) presents interesting properties like the ability to induce hematologic responses (HRs) and molecular responses (MRs) in patients with JAK2 mutation. We report on the response to IFNα therapy in a cohort of 31 essential thrombocythemia (ET) patients with CALR mutations (mean follow-up of 11.8 years). HR was achieved in all patients. Median CALR mutant allelic burden (%CALR) significantly decreased from 41% at baseline to 26% after treatment, and 2 patients even achieved complete MR. In contrast, %CALR was not significantly modified in ET patients treated with hydroxyurea or aspirin only. Next-generation sequencing identified additional mutations in 6 patients (affecting TET2, ASXL1, IDH2, and TP53 genes). The presence of additional mutations was associated with poorer MR on CALR mutant clones, with only minor or no MRs in this subset of patients. Analysis of the evolution of the different variant allele frequencies showed that the mutated clones had a differential sensitivity to IFNα in a given patient, but no new mutation emerged during treatment. In all, this study shows that IFNα induces high rates of HRs and MRs in CALR-mutated ET, and that the presence of additional nondriver mutations may influence the MR to therapy.

Introduction

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are clonal hematologic malignancies characterized by deregulated hematopoietic progenitor proliferation leading to erythrocytosis and thrombocytosis in polycythemia vera (PV) and essential thrombocythemia (ET), respectively. MPNs are linked to the somatic acquisition of genetic alterations targeting genes involved in intracellular signaling pathways, the most frequent being the JAK2V617F mutation, found in ∼95% of PV, 60% of ET, and 50% of patients with primary myelofibrosis (PMF), respectively.1,2 However, monoclonal patterns of hematopoiesis were observed in some ET patients with the wild-type JAK2 gene, suggesting the existence of other mutations.3 Indeed, activating mutations in the MPL gene have been identified in 5% to 10% of patients with JAK2V617F-negative ET or PMF.4 More recently, the presence of mutations in the calreticulin (CALR) gene has been reported in the majority of ET or PMF patients with unmutated JAK2 and MPL.5,6 Many different mutations were described in exon 9 of CALR, the most frequent being a deletion of 52 bp (type 1 mutation) found in ∼50% of patients and an insertion of 5 bp (type 2 mutation) in ∼30% of patients. These CALR mutations probably contribute to the MPN phenotype because they induce unregulated cell growth in the absence of cytokine in vitro,5 and they also represent a novel molecular marker that will improve the accuracy of ET and PMF diagnosis.7

The main goal of cytoreductive treatment in PV and ET is currently to prevent severe thrombohemorrhagic complications.8,9 However, a proportion of patients transform to secondary myelofibrosis (MF), myelodysplastic syndrome, or acute myeloid leukemia (AML). No therapy has been shown to prevent such life-threatening evolutions, although the recent development of Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors improved the outcome of PMF patients.10 Interferon-α (IFNα) therapy is highly efficient at reducing blood cell counts in MPN patients11-13 and was shown to restore polyclonal hematopoiesis or eradicate cytogenetic abnormalities in selected patients, suggesting a targeted action on the malignant clone.14 In a phase 2 study of pegylated IFNα (peg-IFNα) in PV patients, we showed a targeted action of peg-IFNα on JAK2-mutant cells as deep molecular responses (MRs) were observed in these patients,15 an effect also reported later in JAK2V617F-mutated ET patients.13

However, the mutational landscape of MPN is complex, and many additional mutations in genes involved in the regulation of epigenetics (TET2, EZH2, ASXL1, DNMT3A, IDH1/2) or messenger RNA splicing (SRSF2, U2AF1, SF3B1) or in oncogenes (TP53, NRAS, KRAS) have been subsequently identified.16-18 These additional mutations may accumulate in individual patients either in 1 or in different subclones.19-21 The prognosis of MPN patients has been found to be dependent on the presence and the number of some of these additional mutations, such as ASXL1, SRSF2, IDH1, or IDH2,22,23 whereas TP53 mutations are highly correlated to the development of acute transformation.21,24,25 Interestingly, particular combinations of mutations could better define subgroups of patients with different outcomes.26 Such molecular complexity could also affect the response to treatment. For example, we found that a TET2-mutated clone could persist after IFNα therapy, whereas JAK2-mutated cells were eradicated in the same patient.27

A preliminary study in 2 ET patients showed that peg-IFNα therapy resulted in a drastic reduction in the CALR mutant allele burden, suggesting that this drug could also target CALR-mutated cells.27 In the present study, we scrutinized the hematologic responses (HRs) and MRs of 31 CALR-mutated ET patients treated with peg-IFNα. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed to detect the presence of additional mutations in a series of genes of prognostic value in MPNs, and we analyzed their evolution during peg-IFNα therapy to gain insight into the response of molecularly defined subclones to IFNα in vivo.

Methods

Patients and inclusion criteria

Five institutions participated in the study: Saint-Louis Hospital, Paris, France; Brest University Hospital, Brest, France; Henri Mondor Hospital, Creteil, France; Nimes Hospital, Nimes, France; and Hamad General Hospital, Doha, Qatar. Inclusion criteria in this study were as follows: ET diagnosed according to World Health Organization criteria; presence of a CALR mutation; treatment with peg-IFNα for at least 3 months; at least 3 sequential blood samples available, including 1 taken before peg-IFNα therapy (the third sample being required for confirmation of MR after an interval of at least 6 months); and written informed consent for molecular analyses, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In this observational study, off-label treatment with IFNα was decided by the physicians in agreement with local, national, and international guidelines in patients with resistance to or intolerance of standard therapy, or patients younger than 40, or for pregnancy.28 As controls, we studied the evolution of CALR mutations in a series of patients fulfilling the same inclusion criteria but treated either with aspirin only (n = 12) or with hydroxyurea (HU; n = 14). The study has been approved by local institutional review boards.

Response criteria

Clinical responses and HRs were assessed according to the European LeukemiaNet criteria.29 For quantitative changes in CALR mutant allele burden, we used the following definitions: complete MR (CMR) when CALR mutation was reduced to undetectable levels, partial MR (PMR) when the CALR mutant allele burden decrease was >50%, and minor MR (mMR) when a 25% to 49% reduction in the mutant CALR level was observed.

CALR mutation analysis

Total DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples using Qiagen blood DNA minikits. Patient’s DNAs were centralized in Saint-Louis Hospital, Paris, and the CALR gene mutations were searched using direct Sanger sequencing of exon 9. CALR mutant allele burden was evaluated by high-resolution sizing of fluorescent dye-labeled polymerase chain reaction amplification of exon 9, allowing us to determine the peak area ratio between mutant and wild-type alleles (GeneMapper software; Life Technologies). Both sequencing and fragment analysis were performed on a 3500xL DX Genetic Analyzer (Life Technologies) with a sensitivity of ∼1%. MR categories were assigned according to results from fragment analysis where linearity was determined by dilution range of wild-type and CALR mutant DNA mix.

NGS analysis

We designed a targeted resequencing strategy using the TruSeq Custom Amplicon method (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA) to design oligo probes specific for the targeted regions of TET2, ASXL1, EZH2, SRSF2, TP53, IDH1 and IDH2 genes using Illumina DesignStudio v1.5 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Our TruSeq Custom Amplicon library comprised 174 amplicons for a panel size of 23 kb simultaneously amplified in a single-tube reaction. Total blood DNA was quantified using a Qubit instrument. We used 250 ng whole blood DNA as input for amplicon library preparation according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This multiple-sample sequence library pool was loaded on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina) with a molarity of 10 pM as verified by real-time quantitative–polymerase chain reaction, and run was performed using a MiSeq Reagent Kit v2 (500 cycles) (Illumina). Obtained sequences were aligned to the reference genome (GRCh37/hg19) using MiSeq Reporter (Illumina). Variants were called in each sample using the samtools-picard-GATK-VEP pipeline, which detected discrepancies determining their type, such as deletions, insertions, and single-nucleotide polymorphisms. The variant allele frequency (VAF) was also determined using these tools.

Statistical analyses

Peg-IFNα treatment efficiency has been analyzed by paired Student t test comparing %CALR before and after treatment. The impact of additional mutations on the MR to peg-IFNα was analyzed by comparing patients with and without additional mutation in the 4 distinct MR subgroups (CMR, PMR, mMR, and no response) using a χ2 test.

Results

Identification of CALR mutations and characteristics of the patients

We performed a direct sequencing of the CALR exon 9 in all 67 JAK2- and MPL-nonmutated ET patients treated with peg-IFNα in our departments who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. A CALR mutation was identified in 31 patients (46%). All these mutations were frameshift mutations resulting from somatic insertions, deletions, or complex insertion/deletions. In 15 of these 31 patients (49%), a type 1 mutation (52-bp deletion, p.L367fs*46) was observed, whereas in 10 patients (32%), a type 2 mutation (5-bp insertion, p.K385fs*47) was identified. As shown in Table 1, 5 less frequent CALR mutations were detected in 6 (19%) patients (p.A382fs*48, E364fs*55, E383fs*48, and K375fs*49 and p.Q365fs*50 in 2 patients).

Clinical and biological characteristics of the 31 ET patients included in the study

| Patient . | Age at diagnosis . | Sex . | CALR mutation . | %CALR at initiation of IFNα . | %CALR at lowest . | Additional mutations . | Best HR . | IFNα treatment duration (mo) . | MR . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 48 | M | Type 1 | 46 | 3 | CHR | 30 | PMR | |

| #2 | 29 | F | Type 2 | 50 | 5 | CHR | 97 | PMR | |

| #3 | 52 | F | Type 2 | 43 | 14 | CHR | 37 | PMR | |

| #4 | 43 | M | Type 1 | 33 | 38 | CHR | 19 | No | |

| #5 | 14 | F | Type 1 | 49 | 42 | CHR | 12 | No | |

| #6 | 25 | F | Type 1 | 50 | 44 | CHR | 38 | No | |

| #7 | 54 | F | Q365fs*50 | 44 | 26 | IDH2 p.R140Q | CHR | 19 | mMR |

| #8 | 45 | M | Type 1 | 20 | 10 | CHR | 22 | PMR | |

| #9 | 55 | M | Type 2 | 35 | 17 | CHR | 46 | PMR | |

| #10 | 39 | F | Q365fs*50 | 47 | 47 | PHR | 36 | No | |

| #11 | 53 | F | Type 1 | 33 | 27 | PHR | 14 | No | |

| #12 | 52 | F | Type 2 | 13 | 5 | CHR | 13 | PMR | |

| #13 | 37 | M | Type 2 | 35 | 36 | CHR | 14 | No | |

| #14 | 44 | M | K375fs*49 | 51 | 48 | CHR | 24 | No | |

| #15 | 32 | F | Type 2 | 41 | 3 | CHR | 30 | PMR | |

| #16 | 33 | F | Type 1 | 32 | 16 | CHR | 6 | PMR | |

| #17 | 26 | M | Type 2 | 44 | 56 | ASXL1 p.R628fs*; IDH2 p.R140Q | CHR | 52 | No |

| #18 | 35 | F | p.E364fs*55 | 19 | 26 | TET2 p.I1160N | PHR | 67 | No |

| #19 | 42 | F | p,E383fs*48 | 17 | 0 | CHR | 20 | CMR | |

| #20 | 49 | F | Type 1 | 55 | 35 | ASXL1 p.Q778* | CHR | 30 | mMR |

| #21 | 38 | F | Type 1 | 33 | 23 | CHR | 51 | mMR | |

| #22 | 19 | F | Type 1 | 58 | 43 | CHR | 30 | mMR | |

| #23 | 28 | F | Type 2 | 41 | 28 | TP53 H365Y | CHR | 67 | mMR |

| #24 | 22 | F | A382fs*48 | NA | NA | PHR | 57 | ND | |

| #25 | 50 | F | Type 1 | 37 | 18 | CHR | 48 | PMR | |

| #26 | 30 | F | Type 1 | 40 | 0 | CHR | 8 | CMR | |

| #27 | 54 | F | Type 2 | 22 | 15 | ASXL1 p.G646fs*12 | CHR | 35 | mMR |

| #28 | 27 | M | Type 2 | 40 | 20 | CHR | 53 | PMR | |

| #29 | 49 | M | Type 1 | 45 | 49 | PHR | 72 | No | |

| #30 | 58 | M | Type 1 | 32 | 31 | PHR | 5 | No | |

| #31 | 46 | M | Type 1 | 46 | 22 | PHR | 19 | PMR |

| Patient . | Age at diagnosis . | Sex . | CALR mutation . | %CALR at initiation of IFNα . | %CALR at lowest . | Additional mutations . | Best HR . | IFNα treatment duration (mo) . | MR . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 48 | M | Type 1 | 46 | 3 | CHR | 30 | PMR | |

| #2 | 29 | F | Type 2 | 50 | 5 | CHR | 97 | PMR | |

| #3 | 52 | F | Type 2 | 43 | 14 | CHR | 37 | PMR | |

| #4 | 43 | M | Type 1 | 33 | 38 | CHR | 19 | No | |

| #5 | 14 | F | Type 1 | 49 | 42 | CHR | 12 | No | |

| #6 | 25 | F | Type 1 | 50 | 44 | CHR | 38 | No | |

| #7 | 54 | F | Q365fs*50 | 44 | 26 | IDH2 p.R140Q | CHR | 19 | mMR |

| #8 | 45 | M | Type 1 | 20 | 10 | CHR | 22 | PMR | |

| #9 | 55 | M | Type 2 | 35 | 17 | CHR | 46 | PMR | |

| #10 | 39 | F | Q365fs*50 | 47 | 47 | PHR | 36 | No | |

| #11 | 53 | F | Type 1 | 33 | 27 | PHR | 14 | No | |

| #12 | 52 | F | Type 2 | 13 | 5 | CHR | 13 | PMR | |

| #13 | 37 | M | Type 2 | 35 | 36 | CHR | 14 | No | |

| #14 | 44 | M | K375fs*49 | 51 | 48 | CHR | 24 | No | |

| #15 | 32 | F | Type 2 | 41 | 3 | CHR | 30 | PMR | |

| #16 | 33 | F | Type 1 | 32 | 16 | CHR | 6 | PMR | |

| #17 | 26 | M | Type 2 | 44 | 56 | ASXL1 p.R628fs*; IDH2 p.R140Q | CHR | 52 | No |

| #18 | 35 | F | p.E364fs*55 | 19 | 26 | TET2 p.I1160N | PHR | 67 | No |

| #19 | 42 | F | p,E383fs*48 | 17 | 0 | CHR | 20 | CMR | |

| #20 | 49 | F | Type 1 | 55 | 35 | ASXL1 p.Q778* | CHR | 30 | mMR |

| #21 | 38 | F | Type 1 | 33 | 23 | CHR | 51 | mMR | |

| #22 | 19 | F | Type 1 | 58 | 43 | CHR | 30 | mMR | |

| #23 | 28 | F | Type 2 | 41 | 28 | TP53 H365Y | CHR | 67 | mMR |

| #24 | 22 | F | A382fs*48 | NA | NA | PHR | 57 | ND | |

| #25 | 50 | F | Type 1 | 37 | 18 | CHR | 48 | PMR | |

| #26 | 30 | F | Type 1 | 40 | 0 | CHR | 8 | CMR | |

| #27 | 54 | F | Type 2 | 22 | 15 | ASXL1 p.G646fs*12 | CHR | 35 | mMR |

| #28 | 27 | M | Type 2 | 40 | 20 | CHR | 53 | PMR | |

| #29 | 49 | M | Type 1 | 45 | 49 | PHR | 72 | No | |

| #30 | 58 | M | Type 1 | 32 | 31 | PHR | 5 | No | |

| #31 | 46 | M | Type 1 | 46 | 22 | PHR | 19 | PMR |

F, female; M, male; ND, not determined; No, absence of MR.

In this cohort of 31 patients, there were 20 women (65%), and mean age at diagnosis of ET was 39.6 years (range 14-58), representative of the population usually selected to receive peg-IFNα therapy (Table 1). Five patients (16%) received peg-IFNα as first therapy, 17 (55%) as second-line therapy after HU (n = 16) or anagrelide (n = 1), and 9 (29%) patients had received >2 lines of therapy before peg-IFNα. At diagnosis, mean platelet count was 1402 × 109/L (range 604-2241), mean white blood cell count was 9.87 × 109/L (range 4.7-15.7), and mean hemoglobin was 13.8 g/dL (range 9.5-15.3). Five patients had palpable splenomegaly, and the mean spleen size by echography (available in 19 patients) was 11.8 cm (range 8-17).

Peg-IFNα treatment induced a decrease in the CALR mutant allele burden

Mean follow-up from diagnosis of ET in this cohort was 142 months (range 23-407), and mean peg-IFNα treatment duration was 34.5 months (range 5-97). The mean starting dose of peg-IFNα therapy was 496 mcg/mo, reduced to 230 mcg/mo during the maintenance phase. At last follow-up, 19 patients (61%) were still treated with peg-IFNα, whereas 12 patients had stopped after having received the drug for a mean time of 29 months (range 5-57). Toxicity led to treatment discontinuation in 6 of these 12 patients, and 6 additional patients stopped after achievement and maintenance of complete clinical response and HR. Adverse events were reported in 16 patients (51%), including positive autoantibodies (n = 3), mood changes (n = 3), asthenia (n = 3), muscle pain (n = 2), headache (n = 2), peripheral neuropathy (n = 2), flulike symptoms (n = 1), neutropenia (n = 1), skin rash (n = 1), and exacerbation of diabetes (n = 1) and sarcoidosis (n = 1).

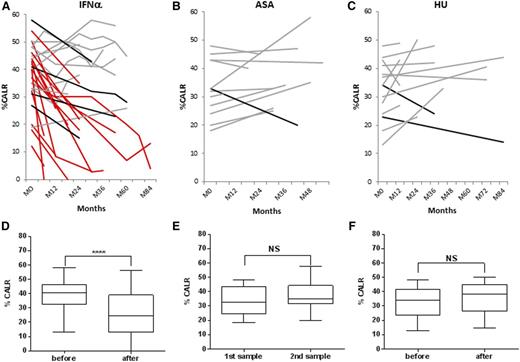

HR to peg-IFNα therapy (European LeukemiaNet criteria) was reached in all the 31 patients, including 24 (77%) complete HR (CHR) and 7 (23%) partial HR (PHR) (Table 1). Considering 5 additional patients who were not included in the molecular analysis because they received peg-IFNα therapy for <3 months, the overall HR rates in our cohort of CALR-mutated ET on intent-to-treat basis were 24/36 (67%) CHR, 7/36 (19%) PHR, and 5/36 (14%) nonresponders. No difference appeared in the HR rate according to the CALR mutation subtype. Taking advantage of a fragment analysis assay,27 we were able to quantify the mutant CALR allele burden (%CALR) in samples taken before and during treatment with peg-IFNα in all but 1 of the patients. In the latter patient, the presence of a very small deletion (1 bp) impeded accurate quantification. Pretreatment %CALR was close to 50% (median %CALR was 41%; range 13-58) in the majority of patients. A significant decrease of the mutant CALR allele burden was observed in the sequential analysis of the patients samples during treatment (Figure 1A), with a median %CALR decrease to 26% (range 0-49) in the last sample (P < .0001) (Figure 1D). In detail, the %CALR decreased in 21 (65%) patients, including 2 CMR, 11 PMR, and 6 mMR. In contrast, in a series of 12 ET patients treated with aspirin only, %CALR remained stable over time, and median %CALR did not change after 34 months of median follow-up (Figure 1B,E). Similarly, in a cohort of 14 patients treated with HU for a median duration of 36 months, %CALR remained stable, from a median of 34% before HU to 38% in the last follow-up sample (Figure 1C,F).

Evolution of CALR mutant allele burden (%CALR) with time. Evolution of %CALR in each patient at different time points during treatment with peg-IFNα (A), aspirin only (B), or HU (C). Patients with CMR or PMR are depicted in red, and patients with no response or mMR are depicted in gray and black, respectively. Median %CALR before treatment and at the last time point during follow-up for patients treated with peg-IFNα (D), aspirin only (E), or HU (F). ASA, aspirin.

Evolution of CALR mutant allele burden (%CALR) with time. Evolution of %CALR in each patient at different time points during treatment with peg-IFNα (A), aspirin only (B), or HU (C). Patients with CMR or PMR are depicted in red, and patients with no response or mMR are depicted in gray and black, respectively. Median %CALR before treatment and at the last time point during follow-up for patients treated with peg-IFNα (D), aspirin only (E), or HU (F). ASA, aspirin.

Treatment duration had no influence on the MR, with a mean time on peg-IFNα therapy of 35, 36.4, and 33.9 months in patients who achieved PMR, mMR, and no MR, respectively. The 2 patients who achieved CMR received peg-IFNα for 20 and 8 months, respectively (Table 1), and in one of them with a type 1 CALR mutation (#26), we observed an extremely rapid MR to peg-IFNα therapy starting from 40% before treatment and dropping down to an undetectable level only 3 months after peg-IFNα therapy initiation. Of note, in these 2 patients who achieved CMR, a second sample confirmed the durable reduction of %CALR to an undetectable level. The mean dose of peg-IFNα received was not higher in patients who achieved PMR or mMR compared with those who had no MR, being respectively 403, 477, and 528 mcg/mo during the induction phase, and 218, 194, and 375 mcg/mo during maintenance, in these 3 categories of patients.

Impact of additional mutations on the MR to peg-IFNα and evolution of the different clones during therapy

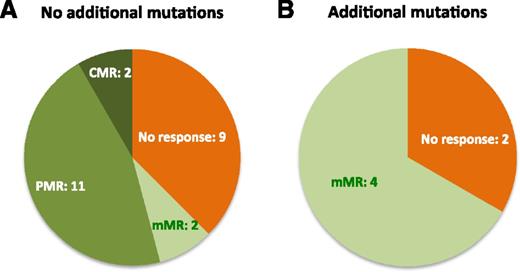

To further investigate the differential decrease of %CALR during peg-IFNα that could be explained by the presence of additional mutations at the clonal level, we analyzed ASXL1, EZH2, IDH1, IDH2, SRSF2, TP53, and TET2 genes in pretreatment samples using a targeted NGS approach. Altogether, 6/31 (19%) of CALR-mutated patients had at least 1 additional mutation affecting TET2 (n = 1), ASXL1 (n = 3), IDH2 (n = 2), or TP53 (n = 1) genes (Table 1). One patient had 2 additional mutations in ASXL1 and IDH2 genes (#17). Patients with additional mutations had a higher rate of no response or mMR compared with patients with CALR mutation alone (Figure 2; P = .026), whereas all the patients with either PMR or CMR had no additional mutations. Furthermore, a small increase in %CALR during peg-IFNα therapy was observed in 2/6 (33%) patients with additional mutations (patients #17 and #18; Table 1), whereas such evolution was observed in only 2/25 (8%) patients with CALR mutation only (patients #4 and #29; Table 1).

Distribution of MRs among patients with or without additional mutations. (A) Patients without additional mutations (N = 24). (B) Patients with additional mutations (N = 6).

Distribution of MRs among patients with or without additional mutations. (A) Patients without additional mutations (N = 24). (B) Patients with additional mutations (N = 6).

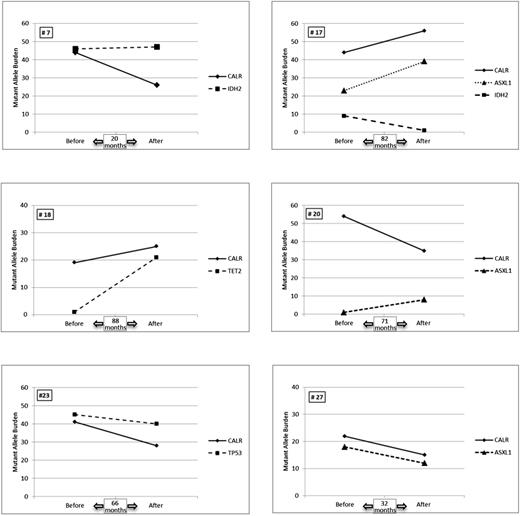

We then compared the evolution of the mutant allele burden of the additional mutations during treatment with that of CALR mutations. Several patterns could be observed (Figure 3). In 2 patients (#23 and #27), a parallel decrease of both %CALR and the additional mutant allele burden (TP53 and ASXL1, respectively) was observed, suggesting that the same clone carried both mutations. In 1 patient (#7), the allele frequency of the additional mutant (IDH2) remained stable, whereas %CALR decreased from 44% to 26% suggesting the existence of 1 CALR-mutated clone that was targeted by peg-IFNα while an IDH2-mutated clone was not. In 2 patients (#18 and #20), we identified a small amount of the additional mutant allele burden (1% for TET2 and 1.5% for ASXL1, respectively) at the time of peg-IFNα treatment initiation. The mean number of reads per amplicon in these samples were very high (2363 and 3186 for #18 and #20, respectively) allowing us to validate each variant: 80 reads for TET2 p.I1160N out of 8142 total reads and 131 reads for ASXL1 p.Q778* out of 7971 total reads. In both patients, the mutant allele burden increased during treatment to 21% and 8.5% for TET2 and ASXL1, respectively, whereas the %CALR remained almost unchanged in patient #18 and decreased from 55% to 35% in patient #20. Different scenarios may explain such evolution in these 2 patients. In patient #18, 2 options are plausible: (1) a very small TET2-mutated/CALR wild-type clone expands during peg-IFNα therapy, whereas a CALR-mutated clone does not vary; and (2) a very small TET2-mutated/CALR-mutated clone expands, whereas a TET2 wild-type/CALR-mutated clone decreases. Similarly, in patient #20: (1) a very small ASXL1-mutated/CALR wild-type clone expands, whereas a CALR only mutated clone decreases; and (2) a very small ASXL1-mutated/CALR-mutated clone expands, whereas an ASXL1 wild-type/CALR-mutated clone dramatically decreases. Altogether, in these 3 patients (#7, #18, and #20), opposing variations of mutant allele frequencies suggest that different clones coexisted in each patient and that they evolved independently during treatment.

Mutant allele frequency evolution in the 6 patients with additional nondriver mutations. The results of the allelic frequencies for each mutation before treatment and at the last time point during follow-up are represented.

Mutant allele frequency evolution in the 6 patients with additional nondriver mutations. The results of the allelic frequencies for each mutation before treatment and at the last time point during follow-up are represented.

In patient #17 with 2 additional mutations in ASXL1 and IDH2 genes, the mutant allele frequencies of CALR and ASXL1 increased in parallel (Figure 3), suggesting the existence of a doubly mutant clone. On the contrary, the mutant allele frequency of IDH2 dramatically decreased in the follow-up sample suggesting the existence of an additional clone harboring only this mutation that was targeted by peg-IFNα treatment. Of note, in this cohort of 31 ET patients with CALR mutations, we did not observe the emergence of new mutations in any patient during peg-IFNα therapy.

Discussion

This study investigated the dynamic evolution of several molecular markers in a cohort of ET patients treated with peg-IFNα.

First, we show that peg-IFNα induces high rates of HRs in CALR-mutated patients whatever the type of CALR mutation (our cohort comprised 7 different mutants). This is an important observation because wild-type CALR protein has been involved in resistance to IFNα therapy in viral hepatitis patients.30 Adverse events reported in this cohort were not different from those observed in JAK2V617F-mutated ET or PV patients, and only 19% of patients discontinued therapy because of toxicity while the exact same proportion stopped for efficacy and sustained HR.

The present study further shows that peg-IFNα is able to reduce CALR mutant malignant clones, as demonstrated by a significant decrease in the %CALR during treatment, including a >50% decrease in %CALR (CMR plus PMR) in 13/31 (42%) patients. Such decrease was not found in patients treated with aspirin only, as well as in patients treated with HU. It was recently reported that ruxolitinib or imetelstat, a telomerase inhibitor, may significantly reduce the %CALR in very small numbers of patients with ET or MF and CALR mutations.31-33

The majority of patients in our study had an elevated CALR mutant allele burden at baseline, in contrast to JAK2V617F-mutated ET patients who frequently carry low levels of mutated cells.34 This high mutant allele burden did not influence the HR rate to peg-IFNα. However, we observed an interpatient variability in the MR with a rapid achievement of CMR in some patients, whereas %CALR remained stable or even increased despite several years of peg-IFNα in others. No predictive factor for MR could be identified in this study. Peg-IFNα can also decrease JAK2V617F allele burden in PV patients with varying intensity.15 The reasons for such heterogeneous responses are still poorly understood, but there is evidence to suggest that the presence of additional mutations might be involved. Indeed, in some patients with both JAK2V617F and TET2 mutations, we observed that TET2-mutated cells persisted, whereas JAK2-mutated cells were dramatically reduced.27 Quintás-Cardama and colleagues also observed a difference in the MR rate according to the presence or absence of TET2 mutations in a cohort of MPN patients treated with peg-IFNα.35 In the present study, we observed a poorer MR rate on CALR mutant clones in patients harboring additional mutations, suggesting that molecular alterations in pathways such as epigenetics may hamper the efficacy of IFNα therapy. The presence of additional mutations such as ASXL1 has been reported to hinder the clinical response to ruxolitinib in MF patients,36 an effect not observed in our cohort of ET patients treated with IFNα.

Evolution of additional mutations during peg-IFNα treatment provided novel information on disease evolution. The first observation is that the different clones can evolve independently and in an unforeseeable way during treatment. For example, the same IDH2 P140L mutation was found in 2 patients. In 1 patient, the mutant allele burden did not change during treatment, whereas in the other, the IDH2 mutant clone significantly decreased. In both cases, the IDH2 mutant allele frequency evolved independently of the %CALR suggesting that IDH2 mutations can be found in CALR wild-type clones. We also observed different evolution patterns in 3 patients with mutations in the ASXL1 gene. In 2 patients, CALR and ASXL1 mutations behaved similarly suggesting that they were present in the same clone. In the third patient, CALR and ASXL1 mutations probably arose in different clones as %CALR decreased whereas the VAF of the ASXL1 mutant increased during follow-up. These results clearly show a differential IFNα targeting on mutated clones. This clonal analysis is, however, inferred from the NGS quantitative data, which is not strictly equivalent to clonal architecture analyses based on genotyping of progenitor colonies grown in vitro. Such a prospective study of clonal architecture is ongoing to confirm these NGS findings and better define the effects of IFNα at the single pluripotent-progenitor level.

Of note, the acquisition of new mutations was not observed during peg-IFNα treatment. This is in accordance with the very low rate of mutation acquisition reported in ET patients.20 However, the appearance of mutations in TET2, ASXL1, and DNMT3a during peg-IFNα treatment has been reported in JAK2-mutated patients using Sanger sequencing (a technique that is known to be usually limited in terms of sensitivity to 10%).35 In our study using NGS, we detected in 2 patients very small clones (∼1%) with mutations in TET2 or ASXL1 in the first sample that reached a VAF of 10% or more after treatment. Therefore, it is possible that the mutations that seemed to appear ex nihilo in the study by Quintás-Cardama et al35 were in fact preexisting in small clones that became detectable using Sanger sequencing when they reached a VAF superior to 10%. However, JAK2V617F mutation may induce genetic instability favoring the appearance of new mutations.37 Such impact on the genome has not been shown for CALR mutations so far.

Myeloid malignancy-associated mutations such as TET2 or ASXL1 mutations have been recently described even in the absence of an overt hematopoietic disease in the general population.38-41 Furthermore, ASXL1 mutations have recently been shown to present similar VAF during the chronic phase and at the time of AML transformation24 suggesting that they were not involved in the emergence of the leukemic clone. On the contrary, 2 studies reported a considerable increase in the VAF of TP53 mutants at the time of AML transformation suggesting that these mutations are fully involved in the leukemic transformation.20,24 Regarding the patient harboring a TP53 mutation in our study, the VAF did not increase (and even slightly decreased) over time during 67 months of peg-IFNα treatment, and no clinical evolution was noticed.

In conclusion, our study is the first to report on clonal evolution of CALR-mutated ET patients treated with IFNα, showing the possible coevolution of several subclones. The presence of additional nondriver mutations affects the response to IFNα therapy, a finding that deserves further investigation to understand the underlying molecular mechanisms and possible impact on clinical outcome.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the genomic platform, Institut Universitaire d'Hématologie (Saint-Louis Institute), Paris-Diderot University, and more particularly to Antonio Alberdi for technical help with NGS equipment.

Authorship

Contribution: B.C., J.-J.K., and C.C. wrote the manuscript; B.C. and J.-J.K. designed research; E.V., B.C., A.C., M.-H.S., N.A.-D., V.U., S.G., and S.C. performed research; J.-C.I., M.A.Y., E.L., C.D., C.C., S.G., and J.-J.K. provided clinical data; E.V., M.-H.S., B.C., and J.-J.K. analyzed data; and all authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jean-Jacques Kiladjian, Centre d’Investigations Cliniques, Hopital Saint-Louis, 1 avenue Claude Vellefaux, 75010 Paris, France; e-mail: jean-jacques.kiladjian@aphp.fr.

References

Author notes

E.V. and B.C. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal