Abstract

Background: In Chuvash polycythemia (CP) (Problemi Gematologii I Perelivaniya Krovi 1974, 10:30), impaired degradation of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1α and HIF-2α from a homozygous germline VHLR200W mutation leads to augmented hypoxic responses during normoxia (Nat Genet 2002, 32:614). In addition to elevated hematocrit, CP is marked by leg varices, benign vertebral hemangiomas, decreased systemic blood pressure, increased systolic pulmonary artery pressure, and by the defining phenotypes of thrombosis and early mortality (Blood 2004, 103:3924; Haematologica 2012, 97:193). There is no effective therapy. While phlebotomy has been recommended for idiopathic polycythemia by the British Committee for Standards in Haematology (Br J Haematol 2005, 130:174) and is administered to some CP patients, its benefits are unknown. Phlebotomy-induced iron deficiency inhibits PHD2 enzyme, the principal negative regulator of HIFs, which further augments hypoxic responses. This affects the transcription of many genes (BCMD 2014, 52:35). Hypoxia-regulated IRAK1 is augmented in inflammation and may promote thrombosis (Circ Res. 2013, 112:103).

Methods: 165 patients with CP were enrolled in a registry between 2001 and 2009 after providing written informed consent. Survival analysis was used to examine the predictors of new thrombosis and death during the follow-up period. mRNA from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was profiled by Affymetrix Human Exon 1.0 ST Array in 42 of the subjects.

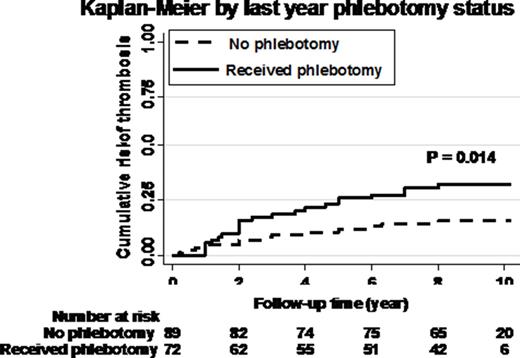

Results: The median age at enrollment was 35 years and 90 participants were females, 25 had a history of one thrombosis, 5 of two thromboses and 3 of three thromboses. In the year prior to study entry, 72 had received phlebotomy therapy (Table 1). In July 2015 the median follow-up was 9.0 years (range 1-14.5). During this follow-up period, 30 (18.2%) participants had one new thrombosis, 6 (3.6%) had two new thromboses and 17 (10.3%) died. The median age of death was 55 years (range 16-76) and deaths were related to thrombotic cerebrovascular accident (n = 4), myocardial infarction (n = 4), mesenteric or portal vein thrombosis (n = 3), other major thromboembolic events (n = 2) and trauma or unknown cause (n = 2). Baseline characteristics of older age, prior thrombosis, pentoxifylline treatment, smoking and splenomegaly were independently associated with greater thrombosis risk during follow-up (P < 0.003). After adjustment for these variables, the estimated probability of new thrombosis at 10 years was 26% in those receiving phlebotomies compared to 12% in those not phlebotomized (log rank P = 0.014) (Figure 1). There was also a trend for increased risk of death with phlebotomy: estimated probability 8.7% versus 3.7% (P = 0.15). Examination of gene transcripts affecting thrombosis by logistic regression identified 12 protective and 16 risk genes at 5% false discovery rate. Upregulation of two mRNAs was of singular significance: 1) IL1RAP, a proximal signaling adaptor of IRAK1 (Immunity 1997, 7: 837) and 2) THBS1, encoding thrombospondin1 (Blood 2015, 125: 399). Both genes have known roles in thrombosis promotion and we previously reported that THBS1 is upregulated in CP (BCMD 2014, 52:35). Further analysis revealed a further upregulation of THBS1 in patients with baseline history of phlebotomy (β=0.41, P=0.046).

Conclusion: These findings underscore a high rate of thrombosis and death in patients with CP and reveal a potential role of increased IRAK1/IL1RAP signaling in these complications. They raise the possibility that phlebotomy therapy has a detrimental rather than beneficial effect, possibly contributed to by increased THBS1 expression.

Baseline characteristics by phlebotomy in the year prior to enrollment. Results in median (interquartile range) or n (%); four without phlebotomy data.

| . | No phlebotomy N=89 . | Received phlebotomy N=72 . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32 (18-48) | 37 (26-49) | 0.08 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 52 (58%) | 34 (47%) | 0.16 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 18 (20%) | 24 (33%) | 0.060 |

| History of thrombosis, n (%) | 20 (23%) | 12 (17%) | 0.4 |

| Splenomegaly, n (%) | 2 (2.3%) | 2 (2.8%) | 0.8 |

| ASA treatment, n (%) | 27 (30%) | 36 (50%) | 0.011 |

| Pentoxifylline, n (%) | 7 (7.9%) | 17 (23.6%) | 0.005 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.4 (18.3-22.9) | 21.6 (19.9-24.6) | 0.010 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 109 (100-123) | 118 (105-124) | 0.6 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 76 (68-84) | 78 (71-83) | 0.8 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 18.1 (16.4-21.0) | 17.9 (16.0-19.8) | 0.5 |

| WBC (per uL) | 5.7 (4.6-7.0) | 5.5 (4.6-6.7) | 0.9 |

| . | No phlebotomy N=89 . | Received phlebotomy N=72 . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32 (18-48) | 37 (26-49) | 0.08 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 52 (58%) | 34 (47%) | 0.16 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 18 (20%) | 24 (33%) | 0.060 |

| History of thrombosis, n (%) | 20 (23%) | 12 (17%) | 0.4 |

| Splenomegaly, n (%) | 2 (2.3%) | 2 (2.8%) | 0.8 |

| ASA treatment, n (%) | 27 (30%) | 36 (50%) | 0.011 |

| Pentoxifylline, n (%) | 7 (7.9%) | 17 (23.6%) | 0.005 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.4 (18.3-22.9) | 21.6 (19.9-24.6) | 0.010 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 109 (100-123) | 118 (105-124) | 0.6 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 76 (68-84) | 78 (71-83) | 0.8 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 18.1 (16.4-21.0) | 17.9 (16.0-19.8) | 0.5 |

| WBC (per uL) | 5.7 (4.6-7.0) | 5.5 (4.6-6.7) | 0.9 |

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This icon denotes a clinically relevant abstract

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal