Key Points

Drug-induced modulation of antibody specificity appears to explain the binding of drug-dependent mAbs to αIIb/β3 integrin.

Drug-dependent platelet antibodies differ greatly from classic hapten-specific antibodies and may be induced by a quite different mechanism.

Abstract

Drug-dependent antibodies (DDAbs) that cause acute thrombocytopenia upon drug exposure are nonreactive in the absence of the drug but bind tightly to a platelet membrane glycoprotein, usually αIIb/β3 integrin (GPIIb/IIIa) when the drug is present. How a drug promotes binding of antibody to its target is unknown and is difficult to study with human DDAbs, which are poly-specific and in limited supply. We addressed this question using quinine-dependent murine monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), which, in vitro and in vivo, closely mimic antibodies that cause thrombocytopenia in patients sensitive to quinine. Using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis, we found that quinine binds with very high affinity (KD ≈10−9 mol/L) to these mAbs at a molar ratio of ≈2:1 but does not bind detectably to an irrelevant mAb. Also using SPR analysis, GPIIb/IIIa was found to bind monovalently to immobilized mAb with low affinity in the absence of quinine and with fivefold greater affinity (KD ≈2.2 × 10−6) when quinine was present. Measurements of quinine-dependent binding of intact mAb and fragment antigen-binding (Fab) fragments to platelets showed that affinity is increased 10 000- to 100 000-fold by bivalent interaction between antibody and its target. Together, the findings indicate that the first step in drug-dependent binding of a DDAb is the interaction of the drug with antibody, rather than with antigen, as has been widely thought, where it induces structural changes that enhance the affinity/specificity of antibody for its target epitope. Bivalent binding may be essential for a DDAb to cause thrombocytopenia.

Introduction

At least 7 distinct mechanisms appear to be capable of causing drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia (DITP).1-3 A major form of DITP, often characterized by acute, sometimes life-threatening thrombocytopenia and bleeding following drug exposure, is caused by a unique type of antibody that recognizes its target on a platelet membrane glycoprotein, usually αIIb/β3 integrin (GPIIb/IIIa), only when the sensitizing drug is present in soluble form.1 Patients treated with quinine or its diastereoisomer, quinidine, are most likely to produce this type of antibody but antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, sedatives, anticonvulsants, and many other agents, including substances in food4,5 and herbal preparations5,6 have also been implicated as triggers.1,7-10 Although platelets are targeted most often, red cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and possibly myeloid precursors in the bone marrow can be similarly affected.11-16

Studies conducted over more than 50 years17-25 have failed to provide a satisfactory explanation for how a small molecule like a drug can promote tight binding of an otherwise harmless antibody to platelets and induce thrombocytopenia. This question is difficult to study using drug-dependent antibodies (DDAbs) from patients who experienced DITP since they are poly-specific,23,26 polyclonal, and usually available only in limited quantities. We recently produced several quinine-dependent murine monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that recognize epitopes located at the amino (N) terminus of the GPIIb β propeller domain only in the presence of quinine, and closely resemble antibodies that cause thrombocytopenia in patients taking quinine in their drug-dependent reactions with platelets in vitro27 and their ability to cause destruction of human platelets in nonobese diabetic/severe combine immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mice given quinine.28 Here, we describe studies of the mechanism by which quinine enables them to react with their target integrin.

Methods

Reagents

Unless otherwise stated, reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Other reagents were protein G sepharose, CM3, CM5, and Amine Coupling Kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 633 (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA), and papain-coated beads (Thermo Scientific, Banockburn, IL).

mAbs

Quinine-dependent, platelet-reactive immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 κ mAbs 314.1 and 314.3 recognizing epitopes at the N terminus of the GPIIb β propeller domain27 and non–drug-dependent mAbs 290.5, 312.8, and AP3 specific for epitopes on the GPIIb/IIIa “head domain”29 were previously described. mAb 10E5, mapped by crystallography to an epitope at the N terminus of GPIIb30 was a gift from Dr Barry Coller of Rockefeller University. Irrelevant, IgG1, κ from murine myleoma clone 21 (MOPC) was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). For flow cytometric experiments, mAb 314.1 and its fragment antigen-binding (Fab) fragment were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 633, respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Fab preparation

Fab fragments were prepared from mAb 314.1 by digestion with papain beads according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Scientific). A 50% slurry of beads suspended in digestion buffer (20 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM EDTA, and 20 mM cysteine pH 7.0) was combined with an equal volume of 314.1 (20 mg/mL) at 37°C for 18 hours. The beads were drained and washed with 10 mM Tris 60 mM iodoacetamide pH 7.5. Supernatants were combined and dialyzed in 20 mM Tris pH 8.0. The mixture was applied to a HiTrap Q HP column (GE Healthcare Uppsala, Sweden) and flow-through containing the Fab was collected and then dialyzed in 50 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid pH 6.0. The solution containing the Fab was applied to a HiTrap SP HP column (GE Healthcare) and the 314.1 Fabs were eluted with 0.2 M NaCl in 50 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid pH 6.0.

Binding of quinine to mAbs 314.1 and 314.3

Control antibody MOPC and mAbs 314.1 and 314.3 were coupled to CM5 sensor chips by amine coupling using the manufacturer’s protocol (Biacore 3000, GE Healthcare). The number of mAb molecules immobilized on a chip was estimated from the change in surface plasmon resonance (SPR) signal produced by the mass of immobilized mAbs at the end of the immobilization process relative to the signal at the start of the process, assuming that 1.0 pg of immobilized mAb increases the SPR signal by 1.0 resonance unit (Biacore 3000 instruction manual, GE Healthcare). All studies were performed with a Biacore 3000 analyzer using Tris-buffered saline (TBS)/0.05% Tween 20 running buffer at 30 μl/min unless otherwise indicated. Quinine at indicated concentrations was injected for 3 minutes followed by buffer alone for 5 minutes. Flow cells were regenerated by increasing the flow rate to 100 μl/min for 5 minutes. The SPR signal produced by the reaction of quinine with mAbs 314.1 and 314.3 minus the signal obtained with MOPC was used for analysis. KD and Bmax for quinine binding were determined using BIAevaluation software (GE Healthcare). The molar ratio of quinine to mAb at saturation was estimated by dividing the number of quinine molecules corresponding to Bmax by the number of mAb molecules immobilized on the chip.

Purification of GPIIb/IIIa

GPIIb/IIIa was purified as described by Fitzgerald et al31 with minor modifications. Platelets were lysed in TBS containing 1% triton X-100 and 1 mM CaCl2. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was added to Concanavalin A beads (GE Healthcare) and bound GPIIb/IIIa was eluted with methyl glucopyranoside. The eluate was added to a column of cyanogen bromide-activated beads (Sigma) coupled to mAb AP2, specific for the GPIIb/IIIa complex.32 GPIIb/IIIa was eluted with Gentle Elute (Pierce/Thermo) and stored in buffer containing 0.1% triton X-100. The resulting material produced two bands of the appropriate size in sodium dodecyl sulfate gels stained with Coomassie blue but no other detectable bands.

Binding of GPIIb/IIIa to mAb 314.1

Control antibody MOPC and mAb 314.1 were coupled to CM3 sensor chips as described earlier. All studies were performed in TBS/1 mM CaCl2/0.1% triton/0.05% Tween 20 running buffer. Quinine 0.1 mM was added to the running buffer as indicated. GPIIb/IIIa at various concentrations was injected for 3 minutes followed by dissociation for 5 minutes. Regeneration was accomplished by perfusion with 10 mM HCl for 30 seconds. SPR signal obtained with mAb 314.1 minus signals obtained with control mAb MOPC were used for analysis.

Flow cytometry

Platelets were isolated from blood of normal group O donors using acidified acid-citrate-dextrose anticoagulant and prostaglandin E1 to minimize activation.28 mAb 314.1 labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 or its Fab fragments labeled with Alexa Fluor 633 were added to 2.4 × 105 platelets in the presence or absence of quinine (0.1 mM) in a final volume of 0.1 mL to produce indicated final concentrations. After 90 minutes at room temperature and without any further dilution, platelet-bound IgG was analyzed by flow cytometry (LSRII; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Platelets were gated by forward vs side scatter and median fluorescence intensity (MFI) was recorded. Specific binding was calculated by subtracting the MFI value obtained in the absence of quinine from the value obtained when the drug was present.

Data analysis

BIAevaluation software (GE Healthcare) was used to generate binding isotherms for analysis of data generated in Biacore studies. Using the BIAevaluation software, data were fit within a 1:1 Langmuir binding model for determination of rate constants. Values in a 10-second window near the end of the Biacore injections were averaged and imported into Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) for nonlinear analysis and into Excel (Microsoft) to develop the Scatchard plots and linear fit of the data points. Results of flow cytometric studies were similarly analyzed using nonlinear regression analysis and Scatchard plots.

Research approvals

Human studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin. Written informed consent was obtained from human participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Results

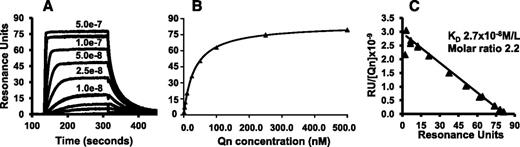

Quinine binds to mAbs 314.1 and 314.3 with high affinity and molar ratio ∼2:1

mAbs 314.1 and 314.3 were linked covalently to CM5 chips as described in “Methods.” Relatively large quantities of mAbs ( ∼3 × 1010 molecules) were immobilized on each chip so that the small ligand quinine (molecular mass, 324 gm/mol) would produce significant SPR signals upon binding. Similar amounts of the irrelevant mAb, MOPC were immobilized on control surfaces. Quinine was perfused over the chips at concentrations ranging from 1.0 nM to 0.5 μM. As shown in Figure 1A, quinine reacted with mAb 314.1 in a dose-dependent manner and rapidly dissociated when the drug was omitted from the perfusate. Binding isotherms and Scatchard plots are shown in Figure 1B-C. KD values obtained in replicate studies are listed in Table 1. The mean KD calculated for binding of quinine to mAb 314.1 (1:1 Langmuir binding model) was 2.7 × 10−8 mol/L. The comparable value for mAb 314.3 was 3.2 × 10−8 mol/L. In 3 independent studies, the calculated ratios of quinine bound to mAb at saturation were 2.2 (range, 2.1 to 2.3) for mAb 314.1 and 1.6 (range, 1.4 to 1.7) for mAb 314.3. The ratio of 2.2 obtained for mAb 314.1 is close to the value of 2.0 expected if quinine binds to the antigen-combining site of antibody. Previously reported sequencing studies showed that mAb 314.3 differs from mAb 314.1 in having an arginine residue at position 107 of the heavy chain complementarity-determining regions (CDR)3.27 The lower ratio (1.6) obtained for binding of quinine to mAb 314.3 could result from chemical linkage of a subset of 314.3 molecules to the chip through the free amino group of R107, thereby denying access of quinine to the CDR and explaining the lower value obtained for binding of quinine to this mAb. By flow cytometry, we compared reactions of Alexa Fluor 488 labeled and unlabeled 314.1 and 314.3 mAbs with intact platelets and found that, at equal mAb concentrations, binding of labeled 314.3 was about 30% lower than that of unlabeled 314.3, indicating that about 30% of the labeled molecules were incapable of bivalent interaction. No such difference was found with mAb 314.1. For this reason, and because quinine-dependent reactions of the two antibodies in vitro and in vivo were very similar,27,28 only mAb 314.1 was used in subsequent studies.

Quinine binds to mAb 314.1 with high affinity. mAb 314.1 and control antibody MOPC were immobilized by amine coupling to a CM5 chip for SPR analysis. Quinine at the indicated concentrations was flowed over the chip surfaces. Specific binding of quinine to mAb 314.1 was calculated as described in “Methods.” (A) Representative sensorgrams illustrating dose-dependent binding of quinine to mAb 314.1. (B) Binding isotherm derived from dose-response curves illustrated in (A). Values shown depict duplicate determinations that were nearly superimposable. (C) Scatchard plot analysis. Line shown is the linear fit for data points obtained in duplicate studies. In the experiment shown, KD for binding of quinine to mAb 314.1: 2.7 × 10−8 mol/L and molar ratio of quinine: mAb at saturation was 2.2. Qn, quinine; RU, resonance unit.

Quinine binds to mAb 314.1 with high affinity. mAb 314.1 and control antibody MOPC were immobilized by amine coupling to a CM5 chip for SPR analysis. Quinine at the indicated concentrations was flowed over the chip surfaces. Specific binding of quinine to mAb 314.1 was calculated as described in “Methods.” (A) Representative sensorgrams illustrating dose-dependent binding of quinine to mAb 314.1. (B) Binding isotherm derived from dose-response curves illustrated in (A). Values shown depict duplicate determinations that were nearly superimposable. (C) Scatchard plot analysis. Line shown is the linear fit for data points obtained in duplicate studies. In the experiment shown, KD for binding of quinine to mAb 314.1: 2.7 × 10−8 mol/L and molar ratio of quinine: mAb at saturation was 2.2. Qn, quinine; RU, resonance unit.

Affinity constants derived from Biacore and flow cytometric studies

| Method . | Ligand . | Receptor . | KD values (mol/L) . | Mean KD (mol/L) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biacore | Quinine | mAb 314.1 | 2.8, 2.5, 2.7 (× 10−8)* | 2.7 × 10−8 |

| Biacore | Quinine | mAb 314.3 | 2.5, 3.6, 3.6 (× 10−8)* | 3.2 × 10−8 |

| Biacore | GPIIb/IIIa - Qn | mAb 314.1 | 8.6, 8.2, 17 (× 10−6)* | 1.1 × 10−5 |

| Biacore | GPIIb/IIIa + Qn | mAb 314.1 | 2.9, 2.9, 1.2, 1.7 (× 10−6)* | 2.2 × 10−6 |

| Flow cytometry | 314.1 Fab + Qn | Platelet GPIIb | 1.9, 2.2, 1.8, 1.7 (× 10−5) | 1.9 × 10−5 |

| Flow cytometry | 314.1 IgG + Qn | Platelet GPIIb | 1.4, 1.4, 1.4, 1.7, 1.6 (× 10−10) | 1.5 × 10−10 |

| Method . | Ligand . | Receptor . | KD values (mol/L) . | Mean KD (mol/L) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biacore | Quinine | mAb 314.1 | 2.8, 2.5, 2.7 (× 10−8)* | 2.7 × 10−8 |

| Biacore | Quinine | mAb 314.3 | 2.5, 3.6, 3.6 (× 10−8)* | 3.2 × 10−8 |

| Biacore | GPIIb/IIIa - Qn | mAb 314.1 | 8.6, 8.2, 17 (× 10−6)* | 1.1 × 10−5 |

| Biacore | GPIIb/IIIa + Qn | mAb 314.1 | 2.9, 2.9, 1.2, 1.7 (× 10−6)* | 2.2 × 10−6 |

| Flow cytometry | 314.1 Fab + Qn | Platelet GPIIb | 1.9, 2.2, 1.8, 1.7 (× 10−5) | 1.9 × 10−5 |

| Flow cytometry | 314.1 IgG + Qn | Platelet GPIIb | 1.4, 1.4, 1.4, 1.7, 1.6 (× 10−10) | 1.5 × 10−10 |

Values shown are the means of replicate determinations performed with the same flow cell.

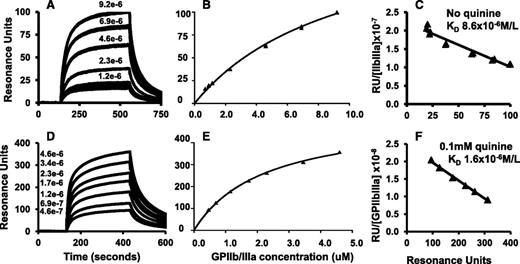

GPIIb/IIIa binds weakly to mAb 314.1 in the absence of quinine, but more tightly when the drug is present

Monoclonal 314.1 and control mAb MOPC were linked to a CM3 chip by amine coupling. GPIIb/IIIa isolated from human platelets was perfused at various concentrations with and without 0.1 mM quinine, at which concentration the quinine-binding sites on 314.1 were saturated based on KD values shown in Table 1. SPR signals obtained with the control mAb MOPC were subtracted from those obtained with mAb 314.1. Because GPIIb/IIIa is free in solution, net SPR signals are the result of monovalent binding of the integrin to the 314.1 antigen-binding sites. Sensorgrams, binding curves, and Scatchard plots are shown in Figure 2A-F. In the absence of quinine, there was a dose-dependent increase in the SPR signal when GPIIb/IIIa at concentrations up to 9.2 μM was perfused over the chip (Figure 1A-B). When the studies were repeated using 0.1 mM quinine in the perfusate, dose-dependent binding was again seen, but SPR signals were significantly stronger (Figure 2D-E). Mean KD values for binding of GPIIb/IIIa to mAb 314.1 without and with quinine were 1.10 × 10−5 mol/L and 2.18 × 10−6 mol/L, respectively. Values obtained in replicate studies are listed in Table 1.

GPIIb/IIIa binds to immobilized mAb 314.1 with low affinity in the absence of the drug and more tightly when the drug is present (monovalent interaction). mAb 314.1 and control antibody MOPC were immobilized by amine coupling to a CM3 chip for SPR analysis. GPIIb/IIIa at various concentrations was perfused over the chip surfaces in the absence (A-C) or presence of 0.1 mM quinine (D-F). (A,D) Representative sensorgrams illustrating dose-dependent binding of GPIIb/IIIa to mAb 314.1 without quinine (A) and with 0.1 mM quinine (D). (B,E) Binding isotherms derived from dose-response curves illustrated in (A) and (D), respectively. (C,F) Scatchard plot analysis. Line shown is the linear fit for data points obtained in duplicate studies. In the experiments shown, KD values for binding of GPIIb/IIIa to immobilized mAb 314.1 were 8.6 × 10−6 and 1.6 × 10−6 mol/L in the absence and presence of quinine, respectively.

GPIIb/IIIa binds to immobilized mAb 314.1 with low affinity in the absence of the drug and more tightly when the drug is present (monovalent interaction). mAb 314.1 and control antibody MOPC were immobilized by amine coupling to a CM3 chip for SPR analysis. GPIIb/IIIa at various concentrations was perfused over the chip surfaces in the absence (A-C) or presence of 0.1 mM quinine (D-F). (A,D) Representative sensorgrams illustrating dose-dependent binding of GPIIb/IIIa to mAb 314.1 without quinine (A) and with 0.1 mM quinine (D). (B,E) Binding isotherms derived from dose-response curves illustrated in (A) and (D), respectively. (C,F) Scatchard plot analysis. Line shown is the linear fit for data points obtained in duplicate studies. In the experiments shown, KD values for binding of GPIIb/IIIa to immobilized mAb 314.1 were 8.6 × 10−6 and 1.6 × 10−6 mol/L in the absence and presence of quinine, respectively.

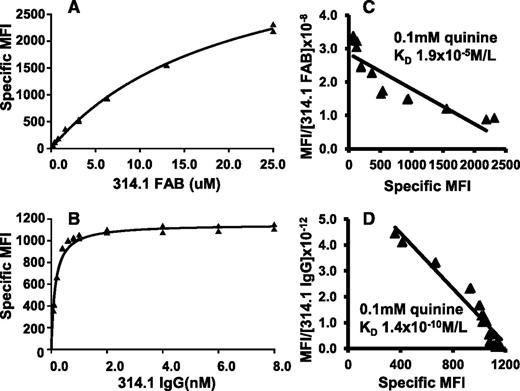

Quinine-dependent reactions of mAb 314.1 and its Fab fragment with intact platelets

Findings shown in Figure 2 demonstrate that mAb 314.1 binds weakly to GPIIb/IIIa in the absence of quinine (monovalent interaction) and more strongly when quinine is present. Previous studies with mAbs33 and human antibodies specific for the human platelet antigen 1a (HPA-1a) carried on GPIIIa34 show that the roughly 80 000 GPIIb/IIIa molecules expressed on the surface of each resting platelet are present at sufficient antigen density to enable ∼40 000 IgG antibodies specific for an epitope on the integrin to react bivalently with this target. To compare bivalent and monovalent, quinine-dependent reactions of mAb 314.1 with the GPIIb/IIIa complex expressed on platelets, labeled 314.1 IgG and its Fab fragments were incubated with resting platelets at various concentrations for 90 minutes. After incubation, platelet-bound fluorescence was analyzed directly by flow cytometry without washing, in order to minimize antibody dissociation resulting from dilution of the reaction mixture. MFI measured in the absence of quinine was subtracted from the value obtained when quinine was present. In preliminary studies in which platelet-bound Alexa Fluor 488 labeled and nonlabeled antibody was detected with an IgG-specific secondary probe, it was found that binding curves obtained with nonlabeled and labeled mAb 314.1 were indistinguishable.

Binding isotherms and Scatchard plots are shown in Figure 3, where it can be seen that quinine-dependent binding of both 314.1 Fab and 314.1 IgG was observed. However, Fab fragments failed to reach saturation at a concentration of about 2.5 × 10−5 M, whereas 314.1 IgG approached saturation at 10−9 M. KD values obtained in replicate studies are listed in Table 1. Effective KD values calculated for quinine-dependent binding of 314.1 Fab and 314.1 IgG were 1.9 × 10−5 mol/L and 1.5 × 10−10 mol/L, respectively.

Bivalent interaction is essential for high avidity, quinine-dependent binding of mAb 314.1 to platelets. mAb 314.1 Fab and IgG, labeled with Alexa Fluor 633 and Alexa Fluor 488, respectively, were incubated with platelets at the indicated concentrations in the presence and absence of 0.1 mM quinine. After incubation, platelet-bound Fab and IgG were measured by flow cytometry without an intermediate washing step. Specific MFI values were obtained by subtracting the signal obtained without the drug from that obtained with the drug. Binding isotherms obtained with (A) mAb 314.1 Fab and (B) 314.1 IgG in a representative study. (C,D) Corresponding Scatchard plots. Lines shown are the linear fit for data points obtained in replicate studies shown in panels A and B. In the experiments shown, KD values for quinine-dependent binding of 314.1 Fab and IgG were 1.9 × 10−5 and 1.4 × 10−10 mol/L, respectively.

Bivalent interaction is essential for high avidity, quinine-dependent binding of mAb 314.1 to platelets. mAb 314.1 Fab and IgG, labeled with Alexa Fluor 633 and Alexa Fluor 488, respectively, were incubated with platelets at the indicated concentrations in the presence and absence of 0.1 mM quinine. After incubation, platelet-bound Fab and IgG were measured by flow cytometry without an intermediate washing step. Specific MFI values were obtained by subtracting the signal obtained without the drug from that obtained with the drug. Binding isotherms obtained with (A) mAb 314.1 Fab and (B) 314.1 IgG in a representative study. (C,D) Corresponding Scatchard plots. Lines shown are the linear fit for data points obtained in replicate studies shown in panels A and B. In the experiments shown, KD values for quinine-dependent binding of 314.1 Fab and IgG were 1.9 × 10−5 and 1.4 × 10−10 mol/L, respectively.

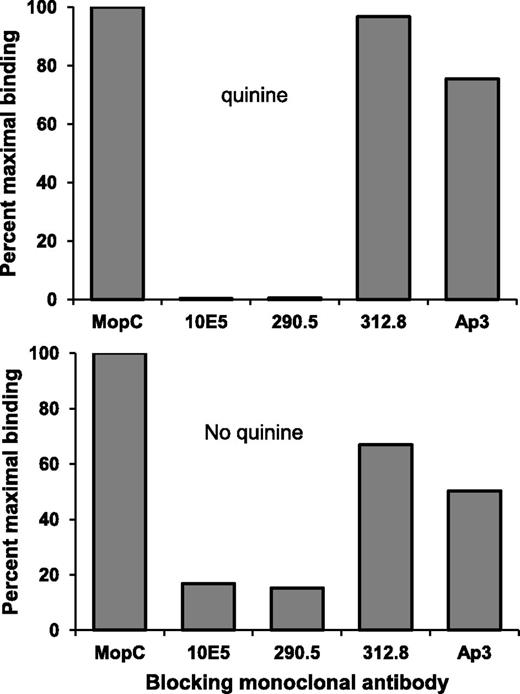

The epitope on GPIIb recognized by mAb 314.1 in the absence of quinine is identical or very similar to the one recognized when quinine is present

Findings shown in Figure 2 leave open the question of whether the epitope on GPIIb/IIIa recognized by mAb 314.1 in the absence of quinine is the same as the one targeted when quinine is present. We previously characterized binding sites for a family of mAbs that recognize various epitopes on the GPIIb/IIIa “head structure.”29 Saturating quantities of four of these mAbs (10E5, 290.5, 312.8, and AP3) were incubated with platelets and the ability of each mAb to block binding of mAb 314.1 subsequently added in the presence and absence of quinine was determined. Figure 4 shows that mAbs 10E5 and 290.5 blocked both quinine-dependent and quinine-independent binding of 314.1, whereas mAbs 312.8 and AP3 had only a minor effect. mAbs 10E5 and 290.5 block each other and their footprint on GPIIb occupies the N terminus of the β propeller domain, the site targeted by mAb 314.1, whereas mAbs 312.8 and AP3 bind elsewhere on the β propeller and on the GPIIIa hybrid domain, respectively.29 Strong inhibition of 314.1 binding only by the former pair of mAbs indicates that 314.1 targets the same epitope or a very similar one on GPIIb, both in the absence and presence of quinine.

mAb 314.1 recognizes the same, or a very similar epitope on GPIIb, in the absence and presence of quinine. Saturating quantities of the mAbs listed on the abscissa were added to platelets and binding of Alexa Fluor 488 labeled mAb 314.1 in the presence (top) and absence (bottom) of quinine was then measured. Both quinine-dependent and quinine-independent binding of mAb 314.1 was blocked by mAbs 10E5 and 290.5, known to be specific for the N terminus of the GPIIb β propeller domain recognized by mAb 314.1. In contrast, binding of mAb 314.1 was relatively unaffected by mAbs 312.8 and AP3, which bind elsewhere on GPIIb and GPIIIa, respectively. Irrelevant mAb MOPC had no effect. Findings shown are representative of 3 independent studies that yielded similar results.

mAb 314.1 recognizes the same, or a very similar epitope on GPIIb, in the absence and presence of quinine. Saturating quantities of the mAbs listed on the abscissa were added to platelets and binding of Alexa Fluor 488 labeled mAb 314.1 in the presence (top) and absence (bottom) of quinine was then measured. Both quinine-dependent and quinine-independent binding of mAb 314.1 was blocked by mAbs 10E5 and 290.5, known to be specific for the N terminus of the GPIIb β propeller domain recognized by mAb 314.1. In contrast, binding of mAb 314.1 was relatively unaffected by mAbs 312.8 and AP3, which bind elsewhere on GPIIb and GPIIIa, respectively. Irrelevant mAb MOPC had no effect. Findings shown are representative of 3 independent studies that yielded similar results.

Discussion

As noted, mAbs 314.1 and 314.3 closely mimic the behavior of antibodies found in patients with DITP in their quinine-dependent reactions with platelets in vitro27 and in their ability to promote drug-dependent destruction of human platelets in a mouse model.28 Even differential reactions of the two mAbs with platelets in the presence of the quinine structural analogs cinchonidine, cinchonine, and quinidine, mirror the behavior of antibodies from patients with quinine-associated DITP,27 the major difference being that the mAbs recognize their targets at lower drug concentrations than their human counterparts. Parallel behavior of the human and murine antibodies in vitro and in vivo favors the likelihood that findings made with the mAbs are relevant to mechanisms responsible for DITP in patients sensitive to quinine.

It is widely thought that drugs or their reactive metabolites usually initiate idiosyncratic sensitivity reactions by binding to an autologous protein and modifying it in such a way that it becomes capable of inducing an immune response.35-39 Quinine does bind weakly to platelets in vitro, probably the result of nonspecific interactions with membranes and membrane proteins, but platelets treated with high doses of quinine and then washed, never bind antibody.18,40 We previously identified a relatively small region in the GPIIIa hybrid domain that is a favored target for antibodies from patients with quinine-induced thrombocytopenia but found that there was no sequence homology between this domain and regions similarly targeted on GPIX and GPIbα by quinine-dependent antibodies, as might be expected if quinine initiated an antibody-target interaction by binding to a structural motif common to these proteins.41 In addition, SPR analysis failed to demonstrate binding of quinine to this region of GPIIIa.41 The most convincing evidence that DDAb binding does not start with binding of quinine to the target protein was provided by Zhu et al who soaked 0.2 mM quinine into crystals of the GPIIb/IIIa headpiece and, in crystallographic studies, were unable to identify any density representing quinine in domains targeted by the “314” mAbs or by human DDAbs.42

Failure to demonstrate an interaction between quinine and protein structural domains recognized by quinine-dependent antibodies suggested an unconventional explanation for binding of DDAbs to their targets: that the drug might react first with the antigen-combining site of a DDAb and modify it, so that it acquires specificity for an epitope on a platelet glycoprotein. When quinine was perfused over chips coated with mAbs 314.1 and 314.3 and the reaction was analyzed by SPR, we found that the drug binds with very high affinity to these mAbs (Figure 1; Table 1). Values calculated for the molar ratio of quinine to mAb at saturation are subject to uncertainty in estimating the number of target mAb molecules bound to a chip on the basis of the increase in SPR signal caused by immobilization of the mAb. Considering this limitation, the mean ratio of 2.2 obtained with mAb 314.1 is a reasonable approximation to the value of 2.0 expected if quinine binds to the antigen-combining site of the mAb. The ratio of 1.6 obtained for binding of quinine to mAb 314.3 is consistent with the same type of interaction, considering that quinine may not have access to about 30% of the antigen-combining sites on this mAb. Failure to detect any interaction between quinine and an irrelevant mAb of the same isotype (MOPC) indicates that binding of quinine to mAbs 314.1 and 314.3 is highly specific. In light of the absolute dependence of these mAbs on quinine for binding to GPIIb/IIIa in standard serologic reactions27 and a previous report showing that tritiated quinine is trapped at the antibody-antigen interface when human quinine-dependent antibodies bind to platelets,19 the most likely explanation for these findings is that quinine recognizes the CDR of mAbs 314.1 and 314.3, and induces structural changes that enhance binding to the epitopes they recognize on GPIIb. High affinity, specific binding of the drug to the two mAbs and failure to demonstrate even a weak interaction between the drug and the domain on GPIIb recognized by antibody, implies that the first step in the quinine-dependent binding of these mAbs to GPIIb/IIIa is binding of quinine to antibody rather than to the targeted integrin.

We next studied monovalent binding of soluble GPIIb/IIIa to immobilized mAb 314.1 in the presence and absence of quinine. Weak but consistent binding of GPIIb/IIIa to this target was observed in the absence of quinine with KD ∼10−5 mol/L. When 0.1 mM quinine was present, the KD decreased to about 2 × 10−6 mol/L, indicating a fivefold increase in affinity. Blockade of both drug-dependent and drug-independent binding of mAb 314.1 by mAbs 10E5 and 290.5 but not by mAbs that bind elsewhere on the GPIIb/IIIa head structure (Figure 4) provide strong evidence that quinine increases the affinity of mAb 314.1 for an epitope that it recognizes weakly in the absence of the drug. Findings made with the “314” mAbs are consistent with the previous suggestion that DDAbs are derived from a pool of naturally occurring antibodies that are weakly reactive with sites on autologous proteins, and that drug increases the affinity of this interaction.1,43

To examine how the avidity of mAb 314.1 is affected by its ability to react with its target bivalently, we compared interactions of directly labeled mAb 314.1 and its Fab fragment with GPIIb/IIIa on the platelet surface. Quinine-dependent binding of 314.1 Fab fragments was detectable but the KD for this interaction was only 2 × 10−5 mol/L, 10× larger than the KD calculated for quinine-dependent monovalent binding of GPIIb/IIIa to mAb 314.1 (Table 1). The reason for this difference is unclear, but could be related to quite different experimental conditions under which the two measurements were made. In either case, the values reflect weak binding typical of most monovalent antibody-target interactions. In contrast, the effective KD for quinine-dependent bivalent-binding of mAb 314.1 was about 1.5 × 10−10, an increase in affinity of about 100 000-fold relative to the value for binding of the 314.1 Fab to intact platelets, and about 10 000-fold relative to the value obtained for monovalent binding of GPIIb/IIIa to immobilized mAb 314.1. Comparative studies of the binding of Fab and intact IgG to cell membrane antigens have shown that bivalent interaction can increase avidity up to 20 000-fold relative to monovalent binding.44 However, numerous variables govern how the valency of antibody binding influences avidity45 and the ternary antibody-drug-antigen complex involved in DDAb binding introduces additional complexity that could favor bivalent interaction. A requirement for bivalent interaction to achieve strong binding of DDAbs to their targets could explain why platelet-specific DDAbs identified in patients with DITP nearly always target GPIIb/IIIa or GPIb/IX, the two most abundant platelet membrane glycoproteins.1,26

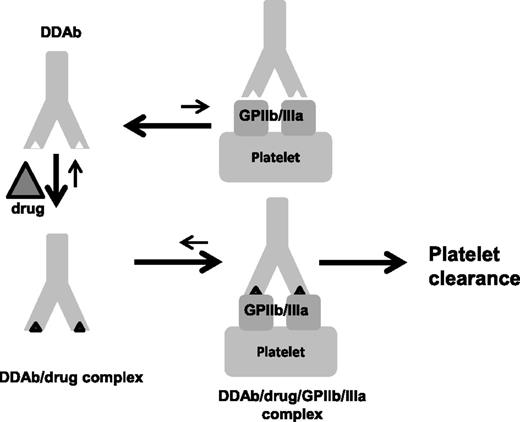

Together, our findings provide evidence that binding of platelet-specific, DDAbs to a target antigen is a two-step process that starts with recognition of antibody by the drug and ends with high-affinity antibody binding to an epitope on a platelet glycoprotein with which the antibody is weakly autoreactive in the absence of the drug (Figure 5). The roughly 2:1 stoichiometry of drug-antibody interaction and other evidence indicating that the drug likely recognizes antibody CDR favors the possibility that drug-binding leads to a structural rearrangement of the CDR that modifies antibody affinity.

A model for DDAb binding. DDAbs of the type induced by quinine and other drugs are weakly autoreactive with a glycoprotein (in this case GPIIb/IIIa) expressed on platelets but the KA for this interaction is too small to be of clinical consequence. When the drug is present, it binds to antibody CDR and induces a structural change that significantly increases KA. When binding occurs, the drug is trapped at the antibody-antigen interface. Under conditions where bivalent antibody binding is possible, the effective KA is increased by orders of magnitude, leading to accumulation of sufficient antibody on the platelet surface to promote platelet clearance.

A model for DDAb binding. DDAbs of the type induced by quinine and other drugs are weakly autoreactive with a glycoprotein (in this case GPIIb/IIIa) expressed on platelets but the KA for this interaction is too small to be of clinical consequence. When the drug is present, it binds to antibody CDR and induces a structural change that significantly increases KA. When binding occurs, the drug is trapped at the antibody-antigen interface. Under conditions where bivalent antibody binding is possible, the effective KA is increased by orders of magnitude, leading to accumulation of sufficient antibody on the platelet surface to promote platelet clearance.

Our findings raise interesting questions about the mechanism(s) by which antibodies of the type that cause thrombocytopenia in patients sensitive to quinine and other drugs are induced. Mice that produced the “314” mAbs were immunized with a combination of GPIIb/IIIa, free quinine, and GPIIb/IIIa linked covalently to C9 of quinine by a succinate bridge27 and were exposed to free quinine in drinking water. In addition to the “314” mAbs, other mAbs specific for: (1) unmodified GPIIb/IIIa, (2) GPIIb/IIIa covalently linked to quinine, and (3) quinine alone were cloned from spleens of these mice. The latter two types of antibody recognize protein to which quinine is chemically linked and their reactions with this target are inhibited by 0.1 mM quinine. However, they fail to recognize unmodified GPIIb/IIIa when soluble quinine is present at any concentration. Thus, they behave like classical “hapten-specific” antibodies.46,47 In contrast, the “314” mAbs bind avidly to GPIIb/IIIa when soluble quinine is present at concentrations as low as 10−8 M and bind equally well at high concentrations of quinine.27 Interestingly, patients sensitive to quinine who make drug-dependent, platelet-reactive antibodies, also produce quinine-specific antibodies that react with quinine-conjugated albumin but do not react with platelets when soluble quinine is present.43 Quinine can undergo various cytochrome p450-dependent structural modifications that could result in reactive intermediates capable of linking to protein and acting as haptens to trigger an immune reaction.48-50 A response to quinine-conjugated proteins could explain hapten (quinine)-specific antibodies typically found in patients with quinine-induced thrombocytopenia.43 The striking difference in serologic behavior of these antibodies, and those that bind to platelets and cause thrombocytopenia, suggests that the two types of antibodies may be induced in quite different ways. Further studies with the mouse model may lead to an understanding of the mechanism that underlies induction of platelet-reactive DDAbs, capable of causing thrombocytopenia in sensitized individuals.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL-13629).

Authorship

Contribution: D.W.B., with the help of J.P. designed the experiments; D.W.B. and M.R. performed the experiments; R.H.A. and D.W.B. wrote the manuscript and supervised the study; and all authors aided in the analysis of the data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Daniel W. Bougie, Blood Research Institute, BloodCenter of Wisconsin, PO Box 2178, Milwaukee, WI 53201; e-mail: daniel.bougie@bcw.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal