In this issue of Blood, Di Buduo et al report an artificial scaffold of the bone marrow niche whereby Bombyx mori silkworm cocoons appeared to coordinate several factors required for megakaryopoiesis and platelet biogenesis.1

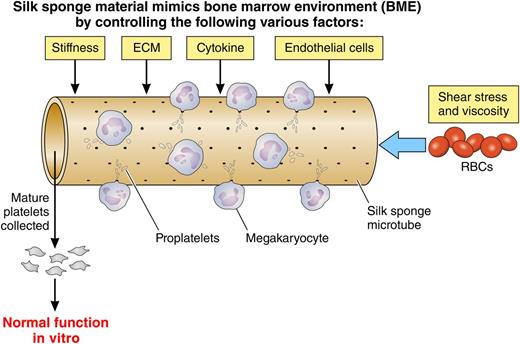

Di Buduo et al demonstrated a combined model to mimic the bone marrow environment to study thrombopoiesis. They previously proposed that silk material-coated microtube structure is capable of recapitulating bone marrow environment, but it failed to obtain a higher rate of mature Mks.8 The improved system included increasing stiffness, extracellular matrix, cytokines, endothelial cells, and modulating shear stress by red blood cells. In this article,1 the authors developed the 3D bioreactor that enhances migration and maturation of Mks, proplatelet generation, and yield of functional platelets. Silk material may be suitable for integration of several factors required for thrombopoiesis ex vivo. Adapted from Figures 5, 6, and 7 in the article by Di Buduo et al beginning on page 2254.

Di Buduo et al demonstrated a combined model to mimic the bone marrow environment to study thrombopoiesis. They previously proposed that silk material-coated microtube structure is capable of recapitulating bone marrow environment, but it failed to obtain a higher rate of mature Mks.8 The improved system included increasing stiffness, extracellular matrix, cytokines, endothelial cells, and modulating shear stress by red blood cells. In this article,1 the authors developed the 3D bioreactor that enhances migration and maturation of Mks, proplatelet generation, and yield of functional platelets. Silk material may be suitable for integration of several factors required for thrombopoiesis ex vivo. Adapted from Figures 5, 6, and 7 in the article by Di Buduo et al beginning on page 2254.

A single bone marrow megakaryocyte (Mk) in the body produces >2000 platelets.2 By recapitulating the chemical and physical signaling that promotes Mk differentiation, maturation, and the release of proplatelets and platelets into the blood stream in vivo, experimental trials ex vivo have tried but failed to achieve similar numbers.3,4 Building on these ex vivo systems have been designs that incorporate switching the culture from 2-dimensional to 3-dimensional (3D) culture environments, for example, using scaffolds made of polyester fabric, hydrogel, or polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) along with cytokines, extracellular matrix, or endothelial cells.5-7 3D environments likely make for more surface area, which could permit more proplatelets to interact with the endothelial wall, increasing the number of platelets acquired.

A series of bioreactor systems that better mimic the bone marrow environment by including extracellular matrix components, surface topography, stiffness, cytokines, and shear stress is also being investigated. Di Buduo et al,1 to obtain higher production efficiency of functional platelets from cultured Mks, prepared a bioreactor that uses a silk sponge, whereby a silk sponge-coated tube structure made by PDMS is also covered by endothelial cells or by vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 on the inside of the tube under the presence of shear stress. The idea of using the silk sponge was previously proposed by the same authors’ group.8 Di Buduo et al added additional factors necessary to fully recapitulate obtaining “functional platelets” through the artificial bone marrow environment (see figure). They previously designed a bioreactor that included both the artificial osteoblast and perivascular niches with the appropriate extracellular matrix proteins and growth factors. However, there were very few Mks displaying proplatelets and producing platelets with impaired function.8 An advance by Di Buduo et al is the incorporation of various factors, ie, composed of stiffness for Mk adhesion, various extracellular matrixes, coated endothelial cells, and an intervention by red blood cells (RBCs) to modulate flow viscosity and shear stress. The subsequent flow by RBCs might influence the conditions of the silk sponge. The silk sponge should control the elements required for mimicking a true bone marrow environment. Thus, the authors concluded that silkworm cocoons contribute to making a comfortable and flexible environment for megakaryopoiesis and platelet biogenesis, which the authors referred to as a “programmable 3D silk bone marrow niche” (see figure).1

Because shear stress has been found to be an important factor in platelet number, Thon et al manufactured a microfluidic bioreactor that also incorporates bone marrow stiffness, the extracellular matrix composition, and other factors modulating shear stress.7 They demonstrated that best rate of shear stress resulted in Mk maturation, as proplatelets were observed within seconds of trapping compared with the several hours seen in static conditions. The shear stress in their system was generated by parallel flows.7 Nakagawa et al found, however, that a confluent system may be more effective, as flow intersecting at 60° achieves a 3.6-fold increase compared with a single-flow system.6 Therefore, a silk-based sponge with PDMS may generate more complicated shear stress conditions by preincubating with RBCs. It has been reported that shear stress increases the expression of RUNX1 in CD41a+ cells,9 also suggesting that shear stress per se facilitates megakaryopoiesis.

Ex vivo platelet production is still far from an industrial scale in transfusion medicine or a drug delivery system, but the bioreactor does offer an excellent model to study megakaryopoiesis from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), as demonstrated by the findings that HSCs and Mks are very close in proximity in the hematopoiesis hierarchy in the bone marrow.10

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal