Key Points

Monoallelic STXBP2 mutations affecting codon 65 impair lymphocyte cytotoxicity and contribute to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

Munc18-2R65Q/W mutant proteins function in a dominant-negative manner to impair membrane fusion and arrest SNARE-complex assembly.

Abstract

Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (F-HLH) and Griscelli syndrome type 2 (GS) are life-threatening immunodeficiencies characterized by impaired cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) and natural killer (NK) cell lytic activity. In the majority of cases, these disorders are caused by biallelic inactivating germline mutations in genes such as RAB27A (GS) and PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, and STXBP2 (F-HLH). Although monoallelic (ie, heterozygous) mutations have been identified in certain patients, the clinical significance and molecular mechanisms by which these mutations influence CTL and NK cell function remain poorly understood. Here, we characterize 2 novel monoallelic hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)-associated mutations affecting codon 65 of STXPB2, the gene encoding Munc18-2, a member of the SEC/MUNC18 family. Unlike previously described Munc18-2 mutants, Munc18-2R65Q and Munc18-2R65W retain the ability to interact with and stabilize syntaxin 11. However, presence of Munc18-2R65Q/W in patient-derived lymphocytes and forced expression in control CTLs and NK cells diminishes degranulation and cytotoxic activity. Mechanistic studies reveal that mutations affecting R65 hinder membrane fusion in vitro by arresting the late steps of soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE)-complex assembly. Collectively, these results reveal a direct role for SEC/MUNC18 proteins in promoting SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and suggest that STXBP2 R65 mutations operate in a novel dominant-negative fashion to impair lytic granule fusion and contribute to HLH.

Introduction

Patients harboring germline inactivating mutations in the PRF1,1 UNC13D,2 STX11,3 STXBP2,4,5 and RAB27A6 genes exhibit immunologic abnormalities that most commonly manifest as familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (F-HLH, types 2-5; also known as “primary” hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis [HLH]) or type 2 Griscelli syndrome (GS).7 F-HLH and GS represent fulminant and often-fatal disorders of the immune system typified by the uncontrolled activation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and natural killer (NK) cells, which secrete high levels of proinflammatory cytokines. Although most F-HLH and GS patients harbor biallelic germline mutations, some individuals harbor only a single mutant allele.8 In these latter individuals, it is unclear whether and how heterozygous mutations lead to disease. Consequently, these patients are often classified as having “secondary” or nonfamilial HLH. However, such a classification is problematic because the therapeutic approaches required for primary and secondary HLH are widely divergent, with primary HLH requiring treatment with chemoimmunotherapeutic agents followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and secondary HLH requiring a much less intensive approach or even no therapy.

The STXBP2 gene encodes Munc18-2, a protein belonging to the SEC/MUNC (SM) family of proteins. SM proteins regulate intracellular membrane trafficking in eukaryotic cells9 by functioning in conjunction with soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs), critical components of the universal membrane fusion machinery. One of the most studied members of the SM family is the neuronal protein Munc18-1, which is proposed to have multiple functions. First, Munc18-1 works as a chaperone by binding to syntaxin (STX)1 and facilitating its transport to the plasma membrane.10-12 Second, Munc18-1 promotes membrane fusion in vitro by facilitating SNARE-complex assembly.13,14 Despite these in vitro observations, it has not yet been confirmed whether Munc18-1 actually facilitates membrane fusion in vivo. Previous studies of Munc18-2 suggest that it regulates granule trafficking in epithelial cells, neutrophils, and mast cells15-17 and the release of α/dense granules and lysosomes in platelets.18 The clinical relevance of Munc18-2 is made evident by the fact that biallelic loss-of-function mutations in STXBP2 lead to F-HLH type 5.4,5,19,20 Nonetheless, it is not well understood how STXBP2 mutations contribute to disease.

In this study, we provide novel mechanistic insights into the pathogenesis of HLH by characterizing the cellular and molecular defects leading to disease in a patient carrying a heterozygous STXBP2 mutation (194G>A; R65Q). In contrast to previously described STXBP2 mutations,5,18,19,21 the R65Q mutation does not affect the expression of Munc18-2, nor does it interfere with the Munc18-2/STX11 interaction or stabilization of STX11. However, presence of the Munc18-2R65Q mutant protein severely impairs cell-mediated cytotoxicity and degranulation in primary HLH CTLs and in control CTLs and NK cells transfected to express the mutant protein. In vitro liposome fusion assays reveal that presence of the Munc18-2 R65Q mutant strongly inhibits SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Similar cellular and biochemical effects were observed following examination of a second STXBP2 mutation (193C>T; R65W) that was identified in an unrelated HLH kindred. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that missense mutations affecting codon 65 of Munc18-2 lead to HLH by conferring a dominant-negative mechanism of action and by interfering with the natural function of wild-type (WT) Munc18-2.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

Mouse anti-CD3, anti-perforin, and anti-granzyme A were from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA), and anti–green fluorescent protein (GFP) was from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). Rabbit anti-STX11 and anti-Munc18-2 were from Synaptic Systems (Goettingen, Germany), anti-MUNC13-4 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX), anti-F-actin was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and anti-C-myc was from Covance (Princeton, NJ). Secondary goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase was from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA), goat anti-rabbit-DyLight 488 was from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL), and goat anti-mouse-ATTO 425 was from Rockland Immunochemicals (Gilbertsville, PA). CD107a-PE (clone H4A3), CD56-APC (clone NCAM16.2), CD8-FITC (clone SK1), and CD3-PerCP (clone SK7) were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA).

Cells

Written consent was obtained from the family of P1 using a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Details of the clinical manifestations and laboratory results of P1 are provided in the supplemental Methods, which can be found on the Blood Web site. Control blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes and processed within 24 hours of venipuncture. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained by density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep; Axis-Shield, Dundee, Scotland) and resuspended in complete medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin; all from Invitrogen/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). CTLs were activated and expanded using Dynabeads (Human T-Expander CD3/CD28; Life Technologies) for 5 days in complete medium. After this time, beads were removed using a magnet, and the cells were used for experiments. The human K562 erythroleukemia and murine P815 mastocytoma cell lines were from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Details for lentiviral transduction and transfection of cells are provided in the supplemental Methods.

Cytotoxicity assays

Cytotoxicity was evaluated using a nonradioactive assay (CytoTox 96; Promega, Madison, WI). To evaluate CTL killing, expanded PBMCs were supplemented with 0.5 μg/mL of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies, mixed with 2 × 104 target P815 cells and incubated in quadruplicate for 4 hours at 37°C. Effector to target-cell ratios ranged from 10 to 0.65 in 100 μL of medium in 96-well V-bottom plates. After 4 hours, plates were centrifuged at 250g for 4 minutes, and 50 μL of supernatant was transferred to a new flat-bottom 96-well plate. Fifty microliters of substrate was added to each well, followed by incubation for 30 minutes at room temperature. The reaction was stopped using 50 μL of stop solution per well. Lactate dehydrogenase release was measured at 490 nm using a 96-well spectrophotometer (SpectraMax; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Percent cytotoxicity was calculated as cytotoxicity (%) = (experiment − effector spontaneous − target spontaneous ÷ target maximum − target spontaneous) × 100. To test NK cell killing, freshly isolated control and P1 PBMCs were incubated at different ratios with K562 target cells, and the assay was performed as described previously for CD8+.22 Target-cell lysis was normalized to the number of NK cells in the PBMCs to obtain the percent NK-specific lysis.

Degranulation assay

To assess NK cell degranulation, PBMCs were incubated in the absence or presence of target cells (K562) at a 1:1 ratio for 4 hours at 37C°. Cells were then labeled using anti-CD107a-PE, CD56-APC, CD8-FITC, and CD3-PerCP. Data were acquired using an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). CD3–CD56+ NK cells were gated and assessed for surface expression of CD107a. Degranulation of CD8+ T cells was measured by incubating cells in the presence or absence of target P815 cells and anti-CD3 antibody at a 1:1 ratio for 4 hours at 37°C as previously described.22 Cells were labeled using anti-CD107a-PE, CD56-APC, CD8-FITC, and CD3-PerCP. CD3+CD8+CD56– cells were gated and assessed for surface expression of CD107a.

Liposome fusion assay

A detailed protocol for protein expression, purification, and proteoliposome reconstitution is provided in the supplemental Methods. A mixture of 45 µL of unlabeled target (t)-SNARE liposomes and 5 µL of labeled (7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole-4-yl)-1,2-dipalmitoyl (NBD)-phosphatidylethanolamine and (N-lyssamine rhodamine B sulfonyl)-1,2-dipalmitoyl (rhodamine)-phosphatidylethanolamine) vesicle (v)-SNARE liposomes was used for the fusion assay.23 Fusion was measured in 96-well FluoroNunc PolySorp plates at 37°C based on the increase in NBD-fluorescence at 538 nm every 2 minutes. Before the reaction was stopped at 120 minutes, 10 µL of 2.5% n-dodecylmaltoside was added to the liposomes, and data were collected for an additional 40 minutes to obtain the maximum NBD signal. Raw NBD-fluorescence data were converted into the percentage of maximum NBD signal.13,24 The initial rate of the fusion reaction at 60 minutes from at least 3 independent experiments was used to calculate the fold activation of fusion. For competition experiments, increasing concentrations of Munc18-1R65Q/R65W were coincubated with Munc18-1WT and t-/v-liposomes for 2 hours on ice followed by assessment of the fusion reaction.

Additional details are provided in the supplemental Methods.

Results

The heterozygous STXBP2R65Q mutation impairs CTL and NK cell function

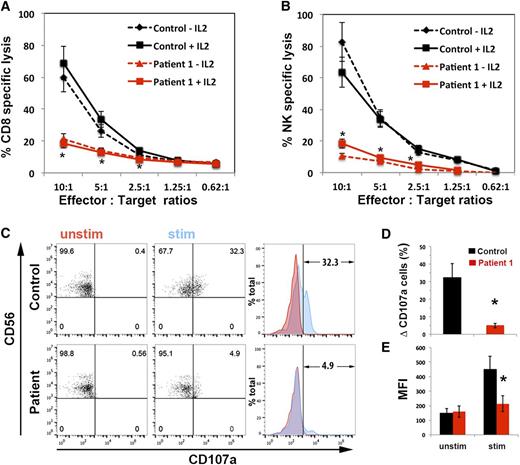

Genetic testing of a 10-year old HLH patient (P1) identified a monoallelic mutation in STXBP2 (194G>A; R65Q). No deletions of the second STXBP2 allele or additional mutations in PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, or RAB27A were identified. To investigate whether the heterozygous STXBP2 R56Q mutation was contributing to the patient’s condition by impairing lymphocyte cytotoxicity, we examined the killing activity of his CTLs and NK cells. In these assays, the cytolytic activity of P1 CTLs and NK cells was significantly reduced (>75%) compared to that of control cells (Figure 1A-B). We also tested whether interleukin (IL)-2 could rescue the cytolytic defect, as has been described for other F-HLH type 5 patients.4,5,20 However, we observed no improvement in killing by P1 CTLs and NK cells despite the presence of IL-2 during the course of the cytotoxicity assay (Figure 1A-B; solid lines). This observation suggested that the STXBP2R65Q mutation was acting in a manner distinct from the previously reported STXBP2 mutations.

CTLs and NK cells expressing the STXBP2R65Q mutation exhibit impaired functions. (A) Cytotoxicity assay to measure CTL-mediated cell killing. PBMCs from control (black) and P1 cells (red) were cultured with CD3/CD28 beads for 5 days and then incubated for 48 hours with (solid line) or without (dashed line) 200 U/mL of IL-2. Equivalent numbers of CD8+ T-cells (Effector) were purified from control and P1 PBMCs and then incubated with anti-CD3 antibody in the presence or absence of P815 target cells (Target) at the indicated cell ratios. The killing assay was run for 4 hours at 37°C, and the amount of lactate dehydrogenase released into the supernatant was quantified using a CytoTox 96 assay. (B) NK cytotoxicity was assessed using control and P1 PBMCs incubated with K562 target cells, as described in panel A. Target-cell lysis was normalized to the number of NK cells in the PBMCs to obtain the percent NK-specific lysis. (C) CD107a assay to measure degranulation. PBMCs from control and P1 were incubated in the presence (stim; blue) or absence (unstim; red) of K562 cells for 4 hours at 37°C. Cells were stained using anti-CD107a-PE, anti-CD56-APC, anti-CD8-FITC, and anti-CD3-PerCP antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD3–CD8–CD56+ cells were gated and analyzed for the appearance of CD107a on the surface after incubation with target cells. Plots are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Graph showing the percentage of cells that increased CD107a staining on stimulation. The term “δ CD107a” reflects the difference between the percentage of NK cells expressing CD107a after K562 stimulation and the percentage of cells expressing surface CD107a after incubation with medium. (E) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values in the CD107a-PE channel of unstimulated (unstim) vs stimulated (stim) cells. Results are the mean ± SD of 3 independent measurements for P1 and 10 different normal controls. *P < .01.

CTLs and NK cells expressing the STXBP2R65Q mutation exhibit impaired functions. (A) Cytotoxicity assay to measure CTL-mediated cell killing. PBMCs from control (black) and P1 cells (red) were cultured with CD3/CD28 beads for 5 days and then incubated for 48 hours with (solid line) or without (dashed line) 200 U/mL of IL-2. Equivalent numbers of CD8+ T-cells (Effector) were purified from control and P1 PBMCs and then incubated with anti-CD3 antibody in the presence or absence of P815 target cells (Target) at the indicated cell ratios. The killing assay was run for 4 hours at 37°C, and the amount of lactate dehydrogenase released into the supernatant was quantified using a CytoTox 96 assay. (B) NK cytotoxicity was assessed using control and P1 PBMCs incubated with K562 target cells, as described in panel A. Target-cell lysis was normalized to the number of NK cells in the PBMCs to obtain the percent NK-specific lysis. (C) CD107a assay to measure degranulation. PBMCs from control and P1 were incubated in the presence (stim; blue) or absence (unstim; red) of K562 cells for 4 hours at 37°C. Cells were stained using anti-CD107a-PE, anti-CD56-APC, anti-CD8-FITC, and anti-CD3-PerCP antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD3–CD8–CD56+ cells were gated and analyzed for the appearance of CD107a on the surface after incubation with target cells. Plots are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Graph showing the percentage of cells that increased CD107a staining on stimulation. The term “δ CD107a” reflects the difference between the percentage of NK cells expressing CD107a after K562 stimulation and the percentage of cells expressing surface CD107a after incubation with medium. (E) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values in the CD107a-PE channel of unstimulated (unstim) vs stimulated (stim) cells. Results are the mean ± SD of 3 independent measurements for P1 and 10 different normal controls. *P < .01.

We next determined whether the defect in killing was due to impaired mobilization of lytic granules. To do so, we measured the expression of CD107a, which serves as a surrogate for degranulation, following exposure of P1 peripheral blood NK cells to K562 target cells25 (Figure 1C). Compared to control NK cells, significantly fewer P1 cells displayed CD107a at the cell surface following stimulation (Figure 1D). Furthermore, the degree of CD107a expression within individual cells was significantly diminished, as evidenced by the reduced mean fluorescence intensity of CD107a after stimulation (Figure 1E). Together, these results confirm that P1, who is heterozygous for the STXBP2R65Q mutation, has a significant and potentially irreversible defect in cytotoxicity that is associated with the impaired release of lytic granules.

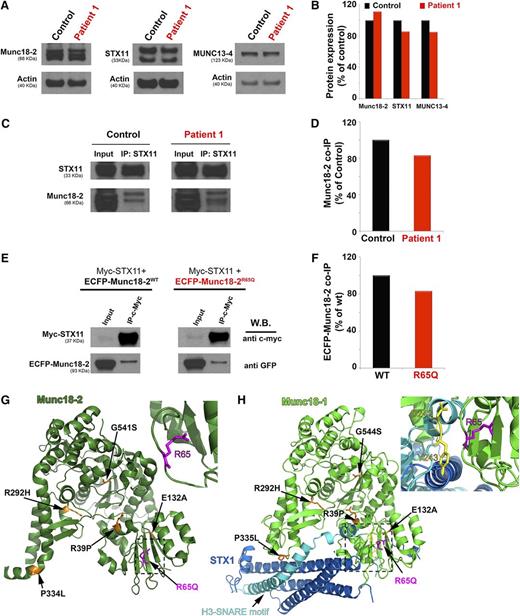

The STXBP2R65Q mutation does not affect FHL protein expression or interfere with the Munc18-2–STX11 interaction

Munc18-2 binds to and stabilizes the expression of STX11. To date, each of the characterized HLH-associated missense STXBP2 mutations reduces Munc18-2 expression and/or impairs the ability of Munc18-2 to interact with and stabilize STX11.4,5,19,21 To better understand why P1 CTLs and NK cells exhibited reduced functions, we evaluated the expression of Munc18-2, STX11, and MUNC13-4 in P1 PBMCs by western blot analysis (Figure 2A). Densitometry analyses revealed that Munc18-2, STX11, and MUNC13-4 were expressed at similar levels in control and patient cells (Figure 2B). To evaluate whether the R65Q mutation affects Munc18-2 binding to STX11, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments in which endogenous STX11 was immunoprecipitated from P1 or control PBMCs, and the amount of associated Munc18-2 was determined by western blot analysis (Figure 2C). In these assays, we observed that Munc18-2 coprecipitated with STX11 equally well in control and P1 cells (Figure 2D). The STXBP2R65Q mutation is monoallelic; therefore, it is possible that the protein observed on western blot analysis and the fraction of Munc18-2 that coimmunoprecipitated with STX11 corresponded to the WT and not the mutant form. To rule out this possibility, we performed immunoprecipitation experiments using HeLa cells that had been transfected to express epitope-tagged versions of WT or mutant Munc18-2. Specifically, HeLa cells were cotransfected with a Myc-tagged STX11 (Myc-STX11), and either enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP)-tagged Munc18-2WT or Munc18-2R65Q. Myc-STX11 was immunoprecipitated using an anti c-Myc antibody, and the amount of ECFP-Munc18-2 that coimmunoprecipitated was evaluated by western blot analysis using an anti-GFP antibody. Again, we observed no difference in the expression or ability of ECFP-Munc18-2WT or ECFP-Munc18-2R65Q to coprecipitate with Myc-STX11 (Figure 2E-F). It was recently proposed that the SNARE protein STX3 can also interact with Munc18-2.21 To assess whether the R65 mutation affects this latter interaction, we completed similar coimmunoprecipitation experiments. Once again, Munc18-2R65Q coimmunoprecipitated STX3 in a manner comparable to Munc18-2WT (supplemental Figure 1B). Thus, the reduced cytotoxicity of P1 cells is not due to diminished expression of Munc18-2 or STX11 or to impaired interaction of Munc18-2 with critical partner proteins such as STX11 and STX3.

The STXBP2 mutation does not influence protein expression or the Munc18-2/STX11 interaction. (A) Western blots showing the expression levels of Munc18-2, STX11, and MUNC13-4 in lysates prepared using PBMCs activated with CD3/28 beads from control (black) or P1 (red). Actin staining of the same membranes was used to assess for equivalent protein loading. (B) Bands in the western blot that corresponded to Munc18-2, STX11, and MUNC13-4 were quantified by densitometry and normalized to the intensity of actin in the same lane. Densitometry results are expressed as the percentage of those obtained using control samples, which were set as 100%. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation experiments using lysates generated from control or P1 PBMCs. Endogenous STX11 was immunoprecipitated (IP) using an anti-STX11 antibody, and the amount of Munc18-2 that coimmunoprecipitated was quantified by western blot analysis. (D) Bands in the western blot that corresponded to the fraction of Munc18-2 that coimmunoprecipitated (co-IP) with STX11 were quantified by densitometry and normalized to the amount of STX11 immunoprecipitated in the same lane. Densitometry results were expressed as the percentage of those obtained in control samples, which were set as 100%. (E) Coimmunoprecipitation experiments using HeLa cells transiently transfected with Myc-STX11 and ECFP-Munc18-2WT (black) or ECFP-Munc18-2R65Q (red). STX11 was immunoprecipitated (IP) using an anti-Myc antibody and the amount of Munc18-2 that coassociated was quantified by western blot analysis using an anti-GFP antibody. (F) Densitometry analysis was performed as described in panel C. In panels A-F, results are representative of 2 independent experiments. (G) Crystal structure of Munc18-2 (Protein Data Bank entry 4CCA) with the R65 residue highlighted in magenta. Previously described HLH-associated Munc18-2 missense mutants are highlighted in orange. (H) The crystal structure of Munc18-1 (green) in complex with STX1 (Habc domain: blue, H3 domain: cyan; Protein Data Bank entry 3C98) reveals that the C-terminal half of the STX1 H3 domain inserts deeply into the Munc18-1 central cavity. The R65 residue (highlighted in magenta) is in proximity to residues D242 and Y243 (yellow) within the STX1 H3 domain but it does not make direct contact with these residues. Munc18-1 residues corresponding to described missense mutations in Munc18-2 are highlighted in orange. The insets in G and H represent a higher magnification of the structure, rotated 90° clockwise in the x-axis.

The STXBP2 mutation does not influence protein expression or the Munc18-2/STX11 interaction. (A) Western blots showing the expression levels of Munc18-2, STX11, and MUNC13-4 in lysates prepared using PBMCs activated with CD3/28 beads from control (black) or P1 (red). Actin staining of the same membranes was used to assess for equivalent protein loading. (B) Bands in the western blot that corresponded to Munc18-2, STX11, and MUNC13-4 were quantified by densitometry and normalized to the intensity of actin in the same lane. Densitometry results are expressed as the percentage of those obtained using control samples, which were set as 100%. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation experiments using lysates generated from control or P1 PBMCs. Endogenous STX11 was immunoprecipitated (IP) using an anti-STX11 antibody, and the amount of Munc18-2 that coimmunoprecipitated was quantified by western blot analysis. (D) Bands in the western blot that corresponded to the fraction of Munc18-2 that coimmunoprecipitated (co-IP) with STX11 were quantified by densitometry and normalized to the amount of STX11 immunoprecipitated in the same lane. Densitometry results were expressed as the percentage of those obtained in control samples, which were set as 100%. (E) Coimmunoprecipitation experiments using HeLa cells transiently transfected with Myc-STX11 and ECFP-Munc18-2WT (black) or ECFP-Munc18-2R65Q (red). STX11 was immunoprecipitated (IP) using an anti-Myc antibody and the amount of Munc18-2 that coassociated was quantified by western blot analysis using an anti-GFP antibody. (F) Densitometry analysis was performed as described in panel C. In panels A-F, results are representative of 2 independent experiments. (G) Crystal structure of Munc18-2 (Protein Data Bank entry 4CCA) with the R65 residue highlighted in magenta. Previously described HLH-associated Munc18-2 missense mutants are highlighted in orange. (H) The crystal structure of Munc18-1 (green) in complex with STX1 (Habc domain: blue, H3 domain: cyan; Protein Data Bank entry 3C98) reveals that the C-terminal half of the STX1 H3 domain inserts deeply into the Munc18-1 central cavity. The R65 residue (highlighted in magenta) is in proximity to residues D242 and Y243 (yellow) within the STX1 H3 domain but it does not make direct contact with these residues. Munc18-1 residues corresponding to described missense mutations in Munc18-2 are highlighted in orange. The insets in G and H represent a higher magnification of the structure, rotated 90° clockwise in the x-axis.

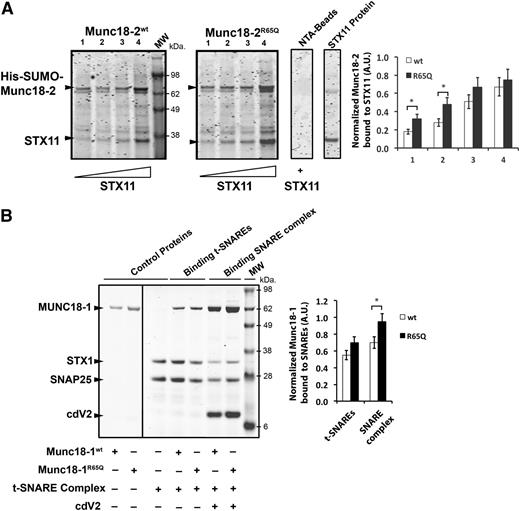

To understand how the R65Q mutation influences Munc18-2 function, we mapped the location of R65 in the crystal structure of Munc18-221 (Figure 2G; magenta residue and arrow) and in the structure of its neuronal homolog, Munc18-126,27 (Figure 2H; magenta residue and arrow). We also compared its location to those of reported HLH-associated mutations (Figures 2G-H; residues in orange). Compared to the previously described mutations, the R65 residue lies within a conserved region located in the central cavity of Munc18-1 where the SNARE motif of STX1 is inserted (Figure 2H). The R65 residue of Munc18-1 is at the interface with STX1; however, it does not make direct contact with any residues of STX1, such as D242 and Y243 (Figure 2H; yellow residues). Notably, R65 of Munc18-2 adopts the same special orientation as R65 of Munc18-1, suggesting that it might not be involved in a direct interaction with STX11. To further investigate this possibility, we performed pull-down experiments using purified recombinant proteins. In line with our coimmunoprecipitation experiments, purified Munc18-2WT and Munc18-2R65Q were able to pull down STX11 (Figure 3A). Quantification of the STX11-bound fractions showed that Munc18-2R65Q has a slightly higher affinity for STX11 than Munc18-2WT (Figure 3A). Moreover, introduction of the R65Q mutation into Munc18-1 did not affect its ability to bind to t-SNAREs (STX1/SNAP25) and assembled SNARE complexes (Vamp2/STX1/SNAP25; Figure 3B). Interestingly, quantification of bound fractions indicated that Munc18-1R65Q has a significantly greater affinity for SNARE complexes than Munc18-1WT. These results were confirmed by coimmunoprecipitation experiments that showed that Munc18-2R65Q and Munc18-2WT interact with STX11, STX3, and SNAP23 to a similar extent (supplemental Figure 1A-B). These biochemical data are consistent with the crystal structure data and show that the R65 mutation exerts no negative effects on the Munc18-2–SNARE interaction. Indeed, these data suggest that the R65Q mutation might even enhance this physical interaction and thus lead to a dominant-negative effect.

The R65Q mutation does not affect binding of Munc18 proteins to syntaxins, t-SNAREs, or SNARE complexes. (A) Pull-down experiments in which equivalent amounts of recombinant His-SUMO-Munc18-2WT or Munc18-2R65Q were bound to nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (NTA-Beads) and increasing concentrations of recombinant STX11 were added to the beads. Bound fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and coomassie blue staining. Plot shows the amount of STX11 bound to the beads normalized by the amount of Munc18-2WT or R65Q present on the beads. (B) Pull-down experiments in which recombinant His-SNAP25/STX1 (t-SNAREs) or His-Vamp2/STX1/SNAP25 (SNARE complex) were immobilized on NTA-Beads and incubated in the presence of equivalent amounts of either untagged Munc18-1WT or Munc18-1R65Q. Bound fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and coomassie blue staining. Plot shows the amount of Munc18-1WT or R65Q bound to t-SNAREs or SNARE complexes normalized by the amount of STX1 present on the beads. Gels and plots are representative of 2 independent experiments. *P < .05. A.U., arbitrary units; cdV2, soluble domain of Vamp2.

The R65Q mutation does not affect binding of Munc18 proteins to syntaxins, t-SNAREs, or SNARE complexes. (A) Pull-down experiments in which equivalent amounts of recombinant His-SUMO-Munc18-2WT or Munc18-2R65Q were bound to nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (NTA-Beads) and increasing concentrations of recombinant STX11 were added to the beads. Bound fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and coomassie blue staining. Plot shows the amount of STX11 bound to the beads normalized by the amount of Munc18-2WT or R65Q present on the beads. (B) Pull-down experiments in which recombinant His-SNAP25/STX1 (t-SNAREs) or His-Vamp2/STX1/SNAP25 (SNARE complex) were immobilized on NTA-Beads and incubated in the presence of equivalent amounts of either untagged Munc18-1WT or Munc18-1R65Q. Bound fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and coomassie blue staining. Plot shows the amount of Munc18-1WT or R65Q bound to t-SNAREs or SNARE complexes normalized by the amount of STX1 present on the beads. Gels and plots are representative of 2 independent experiments. *P < .05. A.U., arbitrary units; cdV2, soluble domain of Vamp2.

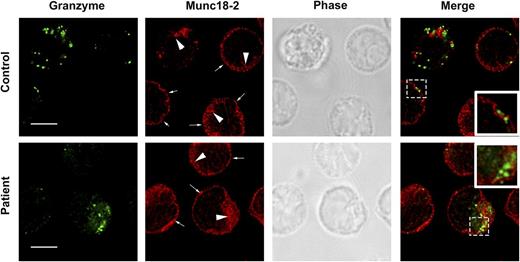

The R65Q mutation does not alter the subcellular localization of STX11 or Munc18-2 or negatively impact lytic granule formation and polarization

One of the proposed functions of Munc18-1 is to act as a chaperone for STX111,28 and facilitate its transport to the plasma membrane. To determine whether the R65Q mutation negatively affects the intracellular distribution of STX11 and Munc18-2, we analyzed the subcellular localization of these proteins using superresolution 2-color stimulated emission depletion microscopy in control and P1 CTLs that were incubated in the presence or absence of anti-CD3-coated P815 target cells. In both control and P1 CTLs, STX11 showed a similar distribution pattern. Specifically, it was primarily localized to intracellular vesicles (Figure 4A; larger arrowheads), whereas a small fraction was found at the plasma membrane (Figure 4A; small arrows). There was no significant colocalization between STX11 and perforin (Figure 4B). The localization of Munc18-2 was also the same in control and P1 cells (Figure 5), where it was diffusely localized throughout the cytoplasm (compatible with the distribution of a soluble protein) and stained internal membrane structures and the plasma membrane.

The R65Q mutation does not affect the subcellular localization of STX11 or the number and polarization of perforin-containing granules. (A) CTLs from a control individual or P1 were incubated in the presence or absence of anti-CD3-coated P815 cells at a 1:1 ratio for 15 minutes at 37°C on polylysine-coated coverslips. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained using mouse anti-perforin-1 antibody, rabbit anti-STX11 antibody and Alexa 633-Phalloidin. Larger arrowheads show the intracellular vesicular pool of STX11. Smaller arrows show the fraction of STX11 localizing at the plasma membrane. Bars represent 5 μm. Insets display a zoomed-in view of the selected area. (B) Pearson’s colocalization coeficient (PCC) between perforin 1 and STX11 in the set of images shown in panel A. Values represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD); n = 15 cells. Quantification of the number of perforin-containing granules per cell (C) and the number of cells containing perforin granules (D) was performed using stimulated emission depletion images (as shown in panel A; nonconjugated). Data represent the mean ± SD; n = 25 cells for panel C and n = 100 cells for panel D. (E) Quantification of the number of CTLs making contact with target cells that display polarized granules. Stimulated emission depletion images (as shown in panel A; conjugated) were used to determine the percentage of CTLs in contact with target cells that exhibited polarized perforin-containing granules at the immunologic synapse among the total number of CTLs containing perforin granules. Data represent the mean ± SD; n = 50 cells.

The R65Q mutation does not affect the subcellular localization of STX11 or the number and polarization of perforin-containing granules. (A) CTLs from a control individual or P1 were incubated in the presence or absence of anti-CD3-coated P815 cells at a 1:1 ratio for 15 minutes at 37°C on polylysine-coated coverslips. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained using mouse anti-perforin-1 antibody, rabbit anti-STX11 antibody and Alexa 633-Phalloidin. Larger arrowheads show the intracellular vesicular pool of STX11. Smaller arrows show the fraction of STX11 localizing at the plasma membrane. Bars represent 5 μm. Insets display a zoomed-in view of the selected area. (B) Pearson’s colocalization coeficient (PCC) between perforin 1 and STX11 in the set of images shown in panel A. Values represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD); n = 15 cells. Quantification of the number of perforin-containing granules per cell (C) and the number of cells containing perforin granules (D) was performed using stimulated emission depletion images (as shown in panel A; nonconjugated). Data represent the mean ± SD; n = 25 cells for panel C and n = 100 cells for panel D. (E) Quantification of the number of CTLs making contact with target cells that display polarized granules. Stimulated emission depletion images (as shown in panel A; conjugated) were used to determine the percentage of CTLs in contact with target cells that exhibited polarized perforin-containing granules at the immunologic synapse among the total number of CTLs containing perforin granules. Data represent the mean ± SD; n = 50 cells.

The R65Q mutation does not affect the subcellular localization of Munc18-2. CTLs from a control or P1 were incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C on polylysine-coated coverslips. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained using mouse anti-granzyme-A or rabbit anti-Munc18-2 antibody. Large arrowheads show the intracellular pool of Munc18-2. Smaller arrows show the fraction of Munc18-2 localizing at the plasma membrane. Insets display a zoomed-in view of the selected area. Bars represent 5 μm.

The R65Q mutation does not affect the subcellular localization of Munc18-2. CTLs from a control or P1 were incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C on polylysine-coated coverslips. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained using mouse anti-granzyme-A or rabbit anti-Munc18-2 antibody. Large arrowheads show the intracellular pool of Munc18-2. Smaller arrows show the fraction of Munc18-2 localizing at the plasma membrane. Insets display a zoomed-in view of the selected area. Bars represent 5 μm.

To determine whether Munc18-2R65Q compromises membrane trafficking and thus impairs the formation of lytic granules, we quantified the number of perforin-containing granules in control and P1 cells. We observed that the number of lytic granules per cell and the percentage of cells containing granules were essentially the same (Figure 4C-D). We also assessed whether Munc18-2R65Q impairs granule movement to the immunologic synapse (IS) in conjugates containing P1 CTLs and P815 cells. As in control CTLs, lytic granules polarized normally to the IS on target-cell contact (Figure 4A; conjugated). Indeed, quantification of the number of conjugated CTLs containing polarized granules among the total number of CTLs with granules revealed no differences between control and P1 cells (Figure 4E). Together, these results indicate that expression of the Munc18-2R65Q mutant does not impair the formation of lytic granules or their polarization to the IS on T-cell activation. On the contrary, the data strongly suggest that Munc18-2R65Q impairs lytic granule secretion at later steps of the exocytic process.

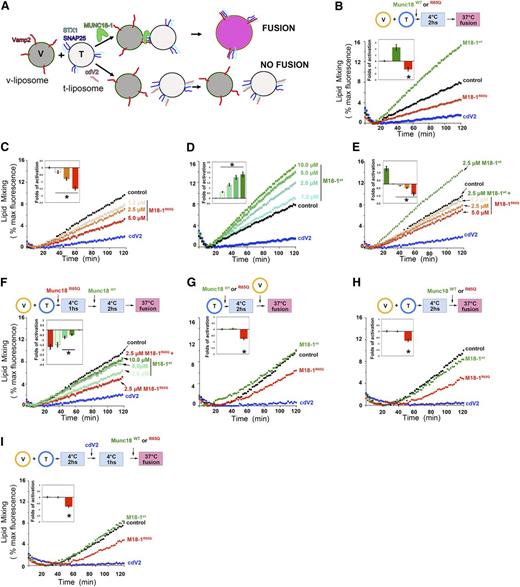

Munc18-2R65Q is a dominant-negative regulator of membrane fusion

SM proteins bind to SNARE complexes through their central cavity and hydrophobic pocket13,24,29-34 and activate membrane fusion in vitro by way of these interactions.13,24,34 MUNCs present differential specificity for SNARE complexes34 ; however, knowledge of the cognate SNARE complexes that cooperate with STX11 and Munc18-2 in CTLs and NK cells is lacking. Currently, there exist no in vitro functional assays with which to test the activity of Munc18-2. Therefore, to determine the effects of the R65Q mutation on membrane fusion, we used a well-established in vitro liposome–liposome fusion assay that incorporates neuronal SNAREs and Munc18-1.23 In this assay, recombinant t-SNARE (STX1, SNAP25) and v-SNARE (Vamp2) proteins are reconstituted into distinct populations of liposomes to generate t- and v-liposomes (Figure 6A). V-liposomes contain fluorescently labeled lipids (NBD- and rhodamine- phosphatidylethanolamine) in such a concentration that fluorescence is quenched. When t- and v-liposomes fuse, fluorescent lipids are diluted and dequench the fluorophores, leading to emission of a fluorescent signal that is directly proportional to the degree of fusion (Figure 6B-I; control).12 Addition of recombinant Munc18-1WT to the reaction resulted in a pronounced induction of fluorescence, indicating strong stimulation of the fusion reaction (Figure 6B).12,13,24,35 In contrast, addition of the soluble domain of Vamp2 (cdV2), a moiety that inhibits membrane fusion by binding to t-SNARE complexes and limiting their ability to interact with v-liposomes, almost completely abolished the fusion reaction (Figure 6B). The addition of Munc18-1R56Q to the liposomes led to a marked reduction in fusion resembling the effect observed using cdV2 (Figure 6B). The magnitude of the inhibitory effect by Munc18-1R56Q was dose dependent (Figure 6C) and highly contrasted with the positive effect of the addition of increasing concentrations of Munc18-1WT (Figure 6D).

The R65Q mutation inhibits membrane fusion in vitro. (A) Schematic depicting the liposome fusion reaction. (B) T- and labeled v-liposomes were preincubated on ice for 2 hours (hs) with control buffer, 2.5 μM Munc18-1WT, 2.5 μM Munc18-1R65Q, or 2.5 μM cdV2. Subsequently, the temperature was increased to 37°C, and the fluorescent signal was read every 2 minutes (min) for a total of 120 minutes. (C) Dose-dependent inhibition of fusion by Munc18-1R65Q. The liposome fusion reaction was performed as in panel B but with increasing concentrations of Munc18-1R65Q. (D) Dose-dependent activation by Munc18-1WT. The liposome fusion reaction was performed as in panel B but with increasing concentrations of Munc18-1WT. (E) Competition experiments using Munc18-1WT and Munc18-1R65Q. T- and v-liposomes were preincubated on ice for 2 hours in the presence of 2.5 μM Munc18-1WT and control buffer or increasing concentrations of Munc18-1R65Q (1.2-5.0 μM). Subsequently, the temperature was increased to 37°C, and the fluorescent signal was read every 2 minutes for a total of 120 minutes. (F) Competition experiments using Munc18-1R65Q and Munc18-1WT. T- and v-liposomes were preincubated on ice for 1 hour in the absence (control) or presence of 2.5 μM Munc18-1R65Q. Munc18-1R65Q-treated liposomes were incubated on ice for 2 hours with increasing concentrations of Munc18-1WT (2.5-10.0 μM). The temperature was increased to 37°C, and fusion was monitored as described above. (G) T-liposomes were incubated in the absence (control) or presence of Munc18-1WT, Munc18-1R65Q, or cdV2 for 2 hours on ice, followed by the addition of v-liposomes. (H) T- and v-liposomes were preincubated for 2 hours on ice to allow the assembly of SNARE complexes, followed by the addition of control buffer, Munc18-1WT, or Munc18-1R65Q. Subsequently, the temperature was raised to 37°C, and lipid mixing was measured. (I) T- and v-liposomes were preincubated 2 hours on ice, and then cdV2 was added to the reaction and incubated for 1 hour on ice. After that, control buffer, Munc18-1WT, or Munc18-1R65Q was added, and the temperature was increased to 37°C to induce lipid mixing. In panels B-I, the blue curve shows the effect when the strong inhibitor cdV2 was added from the beginning of the fusion reaction. Graphs in the insets of panels B-I show the fold activation of at least 3 independent experiments using different liposome preparations. The fold activation was calculated as a ratio of the difference of the initial rate of membrane fusion at 60 minutes in the presence of Munc18-1 minus the initial rate of fusion in the absence of Munc18-1 divided by the initial rate of fusion in the absence of Munc18-1. *P < .05 compared to control level.

The R65Q mutation inhibits membrane fusion in vitro. (A) Schematic depicting the liposome fusion reaction. (B) T- and labeled v-liposomes were preincubated on ice for 2 hours (hs) with control buffer, 2.5 μM Munc18-1WT, 2.5 μM Munc18-1R65Q, or 2.5 μM cdV2. Subsequently, the temperature was increased to 37°C, and the fluorescent signal was read every 2 minutes (min) for a total of 120 minutes. (C) Dose-dependent inhibition of fusion by Munc18-1R65Q. The liposome fusion reaction was performed as in panel B but with increasing concentrations of Munc18-1R65Q. (D) Dose-dependent activation by Munc18-1WT. The liposome fusion reaction was performed as in panel B but with increasing concentrations of Munc18-1WT. (E) Competition experiments using Munc18-1WT and Munc18-1R65Q. T- and v-liposomes were preincubated on ice for 2 hours in the presence of 2.5 μM Munc18-1WT and control buffer or increasing concentrations of Munc18-1R65Q (1.2-5.0 μM). Subsequently, the temperature was increased to 37°C, and the fluorescent signal was read every 2 minutes for a total of 120 minutes. (F) Competition experiments using Munc18-1R65Q and Munc18-1WT. T- and v-liposomes were preincubated on ice for 1 hour in the absence (control) or presence of 2.5 μM Munc18-1R65Q. Munc18-1R65Q-treated liposomes were incubated on ice for 2 hours with increasing concentrations of Munc18-1WT (2.5-10.0 μM). The temperature was increased to 37°C, and fusion was monitored as described above. (G) T-liposomes were incubated in the absence (control) or presence of Munc18-1WT, Munc18-1R65Q, or cdV2 for 2 hours on ice, followed by the addition of v-liposomes. (H) T- and v-liposomes were preincubated for 2 hours on ice to allow the assembly of SNARE complexes, followed by the addition of control buffer, Munc18-1WT, or Munc18-1R65Q. Subsequently, the temperature was raised to 37°C, and lipid mixing was measured. (I) T- and v-liposomes were preincubated 2 hours on ice, and then cdV2 was added to the reaction and incubated for 1 hour on ice. After that, control buffer, Munc18-1WT, or Munc18-1R65Q was added, and the temperature was increased to 37°C to induce lipid mixing. In panels B-I, the blue curve shows the effect when the strong inhibitor cdV2 was added from the beginning of the fusion reaction. Graphs in the insets of panels B-I show the fold activation of at least 3 independent experiments using different liposome preparations. The fold activation was calculated as a ratio of the difference of the initial rate of membrane fusion at 60 minutes in the presence of Munc18-1 minus the initial rate of fusion in the absence of Munc18-1 divided by the initial rate of fusion in the absence of Munc18-1. *P < .05 compared to control level.

To further investigate whether the R65Q mutant functions as a dominant negative, we examined whether Munc18-1R65Q could compete with Munc18-1WT during the membrane fusion reaction. T- and v-liposomes were incubated in the presence of Munc18-1WT (at a nonsaturating concentration) and increasing concentrations of Munc18-1R65Q. We observed that Munc18-1R65Q reduced the positive effect of Munc18-1WT on liposome fusion, again in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6E). Notably, equimolar concentrations of the WT and R65Q mutant proteins resulted in a clear reduction of membrane fusion compared to the control reaction. Although inhibition was partial, it was significant, as shown by the reduction in the fold activation of the rate of the reaction at 60 minutes (Figure 6E; inset). These data provide evidence that Munc18-1R65Q and Munc18-1WT compete for interaction with SNARE complexes during membrane fusion. This conclusion is supported by our coimmunoprecipitation and pull-down experiments, which show that Munc18-1WT and Munc18-1R65Q exhibit enhanced binding to t-SNAREs (STX1/SNAP25) and assembled SNARE complexes (Vamp2/STX1/SNAP25; Figure 3B).

To gain insight into the molecular mechanism of action of the R65Q mutant, we performed experiments in which components of the reaction were added sequentially. First, we tested whether the inhibitory effect of Munc18-1R65Q could be overcome by adding increasing concentrations of Munc18-1WT. The inhibitory effect of Munc18-1R65Q was remarkably strong: a fourfold molar excess of Munc18-1WT was not sufficient to recover fusion levels to those observed in the control reaction (Figure 6F). Second, we investigated whether Munc18-1R65Q might hinder fusion by sequestering t-SNARE proteins in a manner similar to cdV2. To test this hypothesis, we preincubated t-liposomes with Munc18-1WT or Munc18-1R65Q for 2 hours at 4°C. We then added v-liposomes and raised the temperature to 37°C to allow the fusion reaction to proceed. In contrast to Munc18-1WT, which did not affect the level of lipid mixing, Munc18-1R65Q reduced the level of lipid mixing to below the control level (Figure 6G). However, this inhibition was not as strong as that induced by cdV2, suggesting that Munc18-1R65Q might arrest SNARE-complex function at a later stage of the fusion reaction rather than by sequestering t-SNAREs, or it could still be inhibiting SNARE-complex formation but not as potently as cdV2 because of a lower affinity for t-SNAREs. To further investigate these possibilities, we preincubated v- and t-liposomes for 2 hours at 4°C to allow SNARE-complex formation, and then added Munc18-1WT, Munc18-1R65Q, or buffer and increased the temperature. Under these conditions, Munc18-1WT had no effect; however, Munc18-1R65Q inhibited membrane fusion (Figure 6H). This observation suggests that Munc18-1R65Q might interfere with the function of assembled SNARE complexes. Alternatively, Munc18-1R65Q might be inhibiting the assembly of SNARE complexes that are newly formed during the 2-hour incubation. To rule out this latter possibility, we preincubated v- and t-liposomes for 2 hours at 4°C to allow SNARE-complex formation and then added cdV2 for 1 hour at 4°C to titrate away any available t-SNARE proteins and block the formation of new SNARE complexes. Finally, we added Munc18-1WT or Munc18-1R65Q and monitored membrane fusion. These latter studies revealed that Munc18-1R65Q, but not Munc18-1WT, significantly inhibited lipid mixing (Figure 6I). Collectively, the results of these liposome fusion assays indicate that Munc18-1R65Q acts as a dominant negative by arresting SNARE-complex assembly later during the fusion reaction.

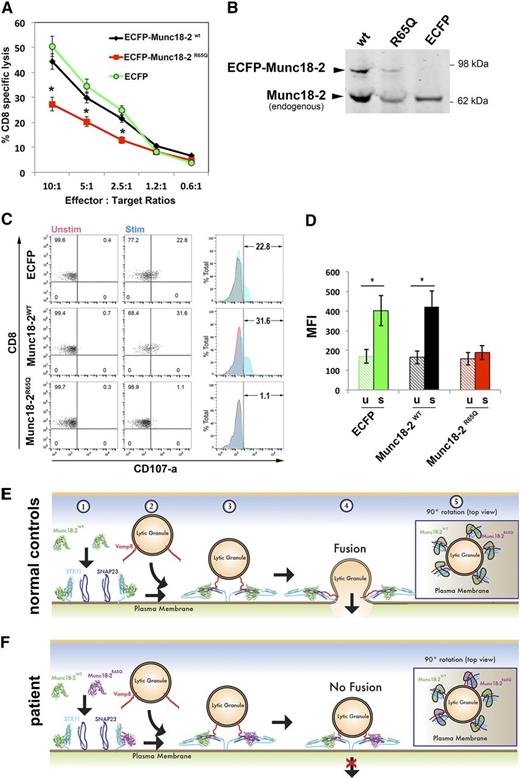

Expression of Munc18-2R65Q in control CTLs reduces target-cell killing

If Munc18-2R65Q were to function in a dominant-negative fashion, we might expect that expression of this mutant in control CTLs would negatively influence cytotoxicity. To test this notion, we transduced control CTLs with lentiviral particles encoding ECFP-Munc18-2WT, ECFP-Munc18-2R65Q, or ECFP alone. The cytotoxic activity of bulk-transfected cells (transduction efficiency of 30% to 40% based on flow cytometric assessment of cyan fluorescent protein expression) was tested against anti-CD3-coated P815 target cells. Consistent with our prior observations, cells expressing ECFP-Munc18-2R65Q exhibited an almost 50% reduction in target-cell killing compared to those expressing ECFP-Munc18-2WT or ECFP (Figure 7A). The expression levels of ECFP-Munc18-2WT and ECFP-Munc18-2R65Q were approximately 20% of endogenous Munc18-2, which when considered in light of our transduction efficiency, suggests that these proteins are expressed comparably (Figure 7B). Therefore, the reduction in cytolytic activity was not due to overexpression of the mutant Munc18-2R65Q protein.

Expression of Munc18-2R65Q in control CTLs reduces cytolytic activity. (A) CD8+ T cells from normal control donors were transduced with lentiviral particles encoding for ECFP-Munc18-2R65Q, ECFP-Munc18-2WT, or ECFP alone. Seven days posttransduction, the cytotoxic activity against anti-CD3-coated P815 cells was tested at the indicated effector to target-cell ratios. (B) Expression levels of ECFP-Munc18-2R65Q and ECFP-Munc18-2wt were compared to endogenous Munc18-2 by western blot analysis using anti-Munc18-2 antibody. (C) CD107a degranulation assay for ECFP-expressing cells. ECFP+ cells were purified by cell sorting and were incubated in the presence (stim; blue) or absence (unstim; red) of CD3-coated P815 cells for 4 hours at 37°C. Cells were stained using anti-CD107a-PE, anti-CD56-APC, anti-CD8-FITC, and anti-CD3-PerCP antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD3+CD8+CD56– cells were gated and analyzed for the appearance of CD107a on the cell surface following incubation with target cells. Plots are representative of 2 independent experiments. (D) Graph showing the percentage of cells that increased CD107a staining after stimulation and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values in the CD107a-PE channel of unstimulated (u) and stimulated (s) cells. Results are the mean ± standard deviation of 2 independent measurements. *P < .01. (E-F) Schematic representation depicting the mode of action of Munc18-2 during lytic granule secretion in a normal control (E) or patient cell carrying the STXBP2R65Q mutation (F). Step 1: soluble Munc18-2WT and Munc18-2R65Q can bind monomeric STX11 on the acceptor membrane (probably the plasma membrane). Step 2: lytic granules approach the plasma membrane on cell activation. Step 3: both Munc18-2WT and Munc18-2R65Q facilitate SNARE-complex assembly between specific v-SNAREs (such as Vamp8) and target-SNAREs (such as STX11 and SNAP23). Step 4: Munc18-2R65Q, but not Munc18-2WT, may arrest some SNARE complexes in a partially zippered state and thus uncouple their coordinated action, which is required for membrane fusion. Step 5: top view of a lytic granule docked at the plasma membrane. The dominant-negative effect of Munc18-2R65Q might result from the fact that it inactivates some of the SNARE complexes involved in the membrane fusion reaction, thereby reducing the energy generated and inhibiting lytic granule fusion with the plasma membrane.

Expression of Munc18-2R65Q in control CTLs reduces cytolytic activity. (A) CD8+ T cells from normal control donors were transduced with lentiviral particles encoding for ECFP-Munc18-2R65Q, ECFP-Munc18-2WT, or ECFP alone. Seven days posttransduction, the cytotoxic activity against anti-CD3-coated P815 cells was tested at the indicated effector to target-cell ratios. (B) Expression levels of ECFP-Munc18-2R65Q and ECFP-Munc18-2wt were compared to endogenous Munc18-2 by western blot analysis using anti-Munc18-2 antibody. (C) CD107a degranulation assay for ECFP-expressing cells. ECFP+ cells were purified by cell sorting and were incubated in the presence (stim; blue) or absence (unstim; red) of CD3-coated P815 cells for 4 hours at 37°C. Cells were stained using anti-CD107a-PE, anti-CD56-APC, anti-CD8-FITC, and anti-CD3-PerCP antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD3+CD8+CD56– cells were gated and analyzed for the appearance of CD107a on the cell surface following incubation with target cells. Plots are representative of 2 independent experiments. (D) Graph showing the percentage of cells that increased CD107a staining after stimulation and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values in the CD107a-PE channel of unstimulated (u) and stimulated (s) cells. Results are the mean ± standard deviation of 2 independent measurements. *P < .01. (E-F) Schematic representation depicting the mode of action of Munc18-2 during lytic granule secretion in a normal control (E) or patient cell carrying the STXBP2R65Q mutation (F). Step 1: soluble Munc18-2WT and Munc18-2R65Q can bind monomeric STX11 on the acceptor membrane (probably the plasma membrane). Step 2: lytic granules approach the plasma membrane on cell activation. Step 3: both Munc18-2WT and Munc18-2R65Q facilitate SNARE-complex assembly between specific v-SNAREs (such as Vamp8) and target-SNAREs (such as STX11 and SNAP23). Step 4: Munc18-2R65Q, but not Munc18-2WT, may arrest some SNARE complexes in a partially zippered state and thus uncouple their coordinated action, which is required for membrane fusion. Step 5: top view of a lytic granule docked at the plasma membrane. The dominant-negative effect of Munc18-2R65Q might result from the fact that it inactivates some of the SNARE complexes involved in the membrane fusion reaction, thereby reducing the energy generated and inhibiting lytic granule fusion with the plasma membrane.

We also examined whether the ECFP-Munc18-2–transduced cells displayed degranulation defects. For this purpose, ECFP+ cells were sorted and assessed for CD107a cell surface appearance after conjugation with anti-CD3-coated P815 target cells. Results showed that degranulation of ECFP-Munc18-2R65Q–expressing cells was almost completely abolished compared to ECFP-Munc18-2WT–expressing and ECFP-expressing cells (Figure 7C-D). Similar results were obtained when YTS NK cells were transfected and used as effectors against EBV-immortalized 721:221 B cells (supplemental Figure 3A-B). Together, these data show that forced expression of Munc18-2R65Q is sufficient to impair cell-mediated cytotoxicity and degranulation despite the presence of endogenous WT Munc18-2.

The STXBP2 R65 mutation is not unique to P1

Interestingly, a search of the HLH database at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center revealed 3 additional unrelated HLH patients with STXBP2 R65 mutations. Two other patients carried the same R65Q mutation in a homozygous (P2) or compound heterozygous (P3) state (Table 1). The third patient (P4) and family harbored a heterozygous 193C>T, R65W mutation. Of note, each of these patients and genetically affected family members exhibited a clinically reportable reduction in NK function, degranulation, or both. To examine whether the R65W mutation also functioned as a dominant negative, we completed biochemical and functional analyses, which revealed that like Munc18-2R65Q, Munc18-2R65W coimmunoprecipitated the same amount of STX11 and STX3 as did Munc18-2WT (supplemental Figure 1A-B). Moreover, Munc18-1R65W inhibited lipid mixing in a dose-dependent manner and functioned in a dominant-negative fashion when incubated in the presence of the WT protein (supplemental Figure 3A-B). Taken together, these results demonstrate that Munc18 proteins containing R65Q/W mutations function to inhibit SNARE-mediated membrane fusion.

Characteristics and laboratory test of F-HLH type 5 patients with Munc18-2 R65 mutations

| Patient . | Age* . | Mutation reported . | NK function† (NR >3.1 LU) . | % CD107a‡ (NR 11-35) . | CD107a-MCF (NR 207-678) . | HLH diagnosis§ . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele 1 . | Allele 2 . | ||||||

| P1 | |||||||

| Proband | 10 y | 194G>A (R65Q) | WT | N/A | 4.8 | 206 | + |

| P2 | 6 y | 194G>A (R65Q) | 194G>A (R65Q) | 0 | N/A | N/A | + |

| P3 | |||||||

| Proband | 3 mo | 194G>A (R65Q) | 1621G>A (G541S) | 0 | N/A | N/A | + |

| Twin brother | 3 mo | 195G>A (R65Q) | WT | 0 | N/A | N/A | − |

| P4 | |||||||

| Proband | 2 y | 193C>T (R65W) | WT | 0 | 7 | 161 | + |

| Mother | 42 y | 193C>T (R65W) | WT | 2.2 | 14 | 446 | − |

| Father | 47 y | WT | WT | 10.6 | 18 | 391 | − |

| Brother | 12 y | 193C>T (R65W) | WT | 2.7 | 16 | 217 | − |

| Sister | 5 y | 193C>T (R65W) | WT | 7.9 | 7 | 75 | − |

| Patient . | Age* . | Mutation reported . | NK function† (NR >3.1 LU) . | % CD107a‡ (NR 11-35) . | CD107a-MCF (NR 207-678) . | HLH diagnosis§ . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele 1 . | Allele 2 . | ||||||

| P1 | |||||||

| Proband | 10 y | 194G>A (R65Q) | WT | N/A | 4.8 | 206 | + |

| P2 | 6 y | 194G>A (R65Q) | 194G>A (R65Q) | 0 | N/A | N/A | + |

| P3 | |||||||

| Proband | 3 mo | 194G>A (R65Q) | 1621G>A (G541S) | 0 | N/A | N/A | + |

| Twin brother | 3 mo | 195G>A (R65Q) | WT | 0 | N/A | N/A | − |

| P4 | |||||||

| Proband | 2 y | 193C>T (R65W) | WT | 0 | 7 | 161 | + |

| Mother | 42 y | 193C>T (R65W) | WT | 2.2 | 14 | 446 | − |

| Father | 47 y | WT | WT | 10.6 | 18 | 391 | − |

| Brother | 12 y | 193C>T (R65W) | WT | 2.7 | 16 | 217 | − |

| Sister | 5 y | 193C>T (R65W) | WT | 7.9 | 7 | 75 | − |

Values below the normal range are in bold type.

LU, lytic units; N/A, not available; NR, normal range at the Clinical Immunology Laboratory, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Age at diagnosis or test.

Cytolytic activity of NK cells.

Percentage of CD107a-expressing cells in degranulation assay.

Patient met (+) or did not meet (−) HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria.

Discussion

In the present work, we identified novel heterozygous mutations in STXBP2 that provide key mechanistic insights into the pathogenesis of HLH and the function of Munc18-2 in CTLs and NK cells. To date, most HLH type 5 patients have harbored biallelic germline STXBP2 mutations, with the majority of these mutations reducing expression of the Munc18-2 protein and/or interfering with its ability to interact with and stabilize STX11.4,5,19,36 To our knowledge, this is the first description and characterization of the Munc18-2R65Q/W mutations, which are unique compared to those previously reported. Specifically, the R65Q mutations do not reduce the levels of Munc18-2 protein, nor do they impair binding to STX11. In contrast, the R65 mutations inhibit the ability of WT Munc18-2 to bind to SNARE complexes and promote membrane fusion. Consistent with this inhibitory effect, CTLs and NK cells from patients harboring the heterozygous Munc18-2R65Q/W mutations exhibited reduced degranulation and cytotoxicity, which could not be restored by the addition of exogenous IL-2. Finally, we observed that forced expression of Munc18-2R65Q in control CTLs or YTS cells significantly reduced degranulation and killing activity. Collectively, these data strongly suggest that these STXBP2 R65 mutations confer a dominant-negative function to the encoded Munc18-2 protein.

The mechanisms by which Munc18-2 orchestrates lytic granule exocytosis have remained poorly understood. Here, we provide direct evidence that Munc18-2 promotes membrane fusion in hematopoietic cells by controlling the final steps of lytic granule release. To understand how the R65Q mutation might lead to HLH, we investigated whether any of the predicted functions for SM proteins might be affected. STX11 is one of the main binding partners of Munc18-2 in immune cells4,5,19 and platelets.18,37 We therefore evaluated the putative chaperone function of Munc18-2 by testing its ability to bind to and localize STX11. Our binding experiments showed a normal binary interaction between the Munc18-2R65Q/W mutants and STX11 or the more recently proposed partner STX3.21 Furthermore, the subcellular distribution STX11 was similar in control and P1 CTLs. Based on these observations, we propose that the R65 mutations do not affect the chaperone function of Munc18-2. Nonetheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that these mutations affect the ability of Munc18-2 to serve as a chaperone for other SNARE proteins.15-17 However, this possibility seems unlikely because microscopic studies revealed no significant alteration in the number of perforin-containing granules or their ability to polarize to the IS in CTLs expressing Munc18-2R65Q.

To probe how heterozygous R65Q mutations might exert their negative effects, we completed in vitro liposome fusion assays. In these assays, mutation of R65 to Q or W in Munc18-1, a highly conserved neuronal homolog of Munc18-2, significantly reduced the ability of WT Munc18-1 to promote lipid mixing, further supporting a dominant-negative mode of action. Consistent with this possibility, the R65 mutants bound normally to monomeric STX11 and STX3, t-SNAREs, and assembled SNARE complexes but impaired the ability of these proteins to mediate membrane fusion. This effect is distinct from those previously reported for SM mutants. For example, an E66A mutation in Munc18-1, which results in reduced lipid mixing in vitro and neurotransmitter release in cultured neurons,31,35 exhibits decreased binding to SNARE complexes but not to STX1. Similarly, mutations in the hydrophobic pocket of Munc18-1 (F115E and E132A), which reduce interaction with the syntaxin N-terminal peptide, disrupt the interaction with SNARE complexes, thereby abolishing activation of membrane fusion in vitro without affecting the binary interaction with STX1.13,21,38,39 Therefore, the codon 65 mutations that we describe represent the first naturally occurring mutations that selectively affect the activating function of an SM protein without affecting interaction with the corresponding monomeric STX or SNARE complexes (Figure 7E-F, steps 1-3). It has been proposed that multiple SNARE complexes (usually 3 to 5) must function cooperatively to generate the energy required to overcome the repulsion forces during membrane fusion.40,41 Therefore, we propose that Munc18-2R65Q/W might function by arresting a variable number of SNARE complexes at a partially assembled intermediate state, which decreases the energy generated by the remaining SNARE complexes and thus hampers the fusion reaction (Figure 7F, steps 4 and 5).

In summary, our data demonstrate that the Munc18-2R65Q/W mutants act as dominant negatives that interfere with the release of lytic granules and thus lead to F-HLH type 5. It is notable that individuals harboring these mutations exhibit a variable age of HLH onset, ranging from 3 months to 10 years (Table 1). Indeed, the mother and brother of P4, who also carry a heterozygous STXBP2R65W mutation, have not yet manifested with HLH despite reduction in NK cell function. Although the reasons for this are not known, it is possible that the degree to which the Munc18-2 mutant proteins inhibit cell function differs depending on expression of the mutant protein (which may vary from cell type to cell type or from one clinical scenario to the next). Alternatively, it is possible that coinheritance of variations in other, as yet unidentified genes modifies the disease phenotype. In conclusion, these studies are the first to highlight the clinical and biological importance of monoallelic STXBP2 mutations and emphasize the importance of in vitro biochemical, microscopic, and cell-based functional assays to investigate the clinical relevance of other known or novel heterozygous HLH-associated genetic alterations.8

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Jingshi Shen (University of Colorado) for providing the sumo-Munc18-1-wt pet28 clone.

This work was supported by a Pew Biomedical Scholar Award (C.G.G.); National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant 1R56AI104872 (C.G.G.); and the Sean Fischel Fund for HLH Research (K.E.N.).

Authorship

Contribution: W.A.S. performed experiments, made the figures, and wrote the manuscript; M.L.S. performed cell culture work, transfections, and immunoprecipitations; M.E.M. assisted with protein purification and cloning; N.P. gathered clinical details on patients and helped write the manuscript; J.V. performed immunologic assays; K.Z. coordinated molecular genetic analyses; K.E.N. recruited P1 and helped with data analysis and writing the manuscript; and C.G.G. designed and interpreted the experiments, performed image acquisition and analysis, edited the figures, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Claudio G. Giraudo, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, 3615 Civic Center Blvd, ARC 816C, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: giraudoc@mail.med.upenn.edu; and Kim E. Nichols, Division of Cancer Predisposition, Department Oncology, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, 262 Danny Thomas Blvd, Memphis, TN 38102; e-mail: kim.nichols@stjude.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal