In this issue of Blood, Inamoto et al provide encouragement that we are reaching the time where we have a robust endpoint to use in large, randomized clinical trials testing novel agents in chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).1

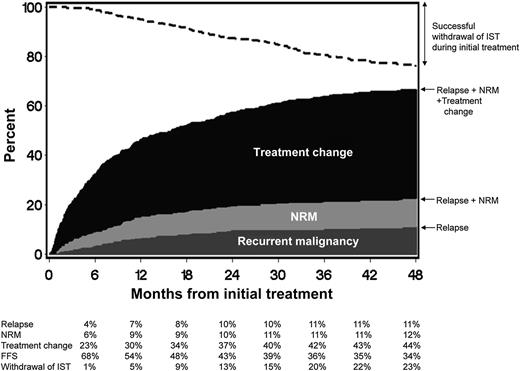

FFS after initial systemic treatment of chronic GVHD. The dark gray area represents treatment failure due to recurrent malignancy. The light gray area represents treatment failure due to NRM, and the black area represents treatment failure due to treatment change. The white area represents FFS. The dashed line represents cumulative incidence of successful withdrawal of all systemic immunosuppressive treatment (IST) during initial treatment. See Figure 1 in the article by Inamoto et al that begins on page 1363.

FFS after initial systemic treatment of chronic GVHD. The dark gray area represents treatment failure due to recurrent malignancy. The light gray area represents treatment failure due to NRM, and the black area represents treatment failure due to treatment change. The white area represents FFS. The dashed line represents cumulative incidence of successful withdrawal of all systemic immunosuppressive treatment (IST) during initial treatment. See Figure 1 in the article by Inamoto et al that begins on page 1363.

A number of randomized phase 3 studies have asked the question of whether adding additional immunosuppression to conventional therapy of chronic GVHD improves outcome.2-5 No studies have shown superiority of the investigational arm. The main issue affecting these trials is that there has been a lack of standardized and validated criteria that adequately measure treatment response. As health care practitioners in bone marrow transplant know, assessing chronic GVHD, particularly in patients with sclerosis, is difficult. What is moveable vs nonmoveable sclerosis? If sclerosis goes from nonmoveable to moveable in part of the body, is that considered a response? How do you know which area of sclerosis represents a fixed deficit that will never respond no matter how intensely you treat the patient? What constitutes a response in a patient with bronchiolitis obliterans? A number of us have grappled with these questions in the last few years, and one of the major problems with clinical trials in this field is precisely that—not all of us may be measuring the same findings, and patients may be graded by different eyes at different follow-up visits. Even with education by specialists on measuring chronic GVHD manifestations, there is still poor inter-rater reliability in the assessment of certain manifestations of chronic GVHD.6 Therefore, trials have been subject to potential bias and problems due to lack of reproducibility of criteria; it has been hard to compare response among trials given the use of home-grown, different criteria.

The last decade has seen an explosion of work done to develop and standardize criteria to diagnose and track response in patients with chronic GVHD.7,8 With the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus for Chronic GVHD came a large body of chronic GVHD criteria that needed to be validated and reduced to clinically relevant and easily reproduced endpoints. Much credit is due to Dr Stephanie Lee, who, with her team of investigators, has been able to validate certain criteria developed by the NIH Consensus, through her prospective natural history study in chronic GVHD. For example, NIH skin score 3 and a high Lee skin symptom score are associated with worse overall survival.9 Worsening of NIH symptom-based lung score over time is associated with higher nonrelapse mortality (NRM) and lower survival.10 Undoubtedly, the refinement of these endpoints will be very useful to measure the burden of disease in individual patients and will be critical in trials looking at agents that are targeting specific areas of chronic GVHD.

The new failure-free survival (FFS) endpoint studied by Inamoto et al takes a very global approach and incorporates objective endpoints (absence of systemic treatment change, NRM, and recurrent malignancy) into 1 composite endpoint (see figure). What is attractive here is the simplicity and the fact that it incorporates elements of response, potential medication toxicities, and blunting of the graft-versus-leukemia effect, which could all occur with immunosuppression. It is a robust and simple endpoint that will likely prove to be very useful in large, randomized blinded studies. This should be attractive to pharmaceutical companies looking to develop immunosuppressants to treat chronic GVHD. An area of concern is that it may not be useful if one incorporates both malignant and nonmalignant patients in chronic GVHD clinical trials unless these patients are stratified, specifically because the composite endpoints include recurrent malignancy. It likely will also need to be validated in the pediatric population. Finally, it may be less useful in nonrandomized studies and studies where there is not a clearly prespecified algorithm defining what should lead to a systemic treatment change.

What the new FFS endpoint does not tell us, however, is how chronic GVHD is impacting a particular patient, what manifestations are affecting them, and exactly in what pattern they are responding. Therefore, it is critical that all the work that has been started by the NIH Consensus and others continue, as we desperately need endpoints in chronic GVHD-related symptoms, activity, damage, and disability. The ultimate goal we all strive for is to see individual patients respond by completely losing their GVHD manifestations and not simply by failing to progress.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal