In this issue of Blood, Branford et al report that the prognosis of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) correlates with the rate of breakpoint cluster region–Abelson (BCR-ABL1) decline.1

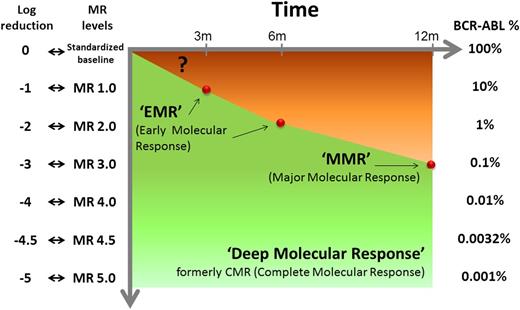

Levels of molecular response and corresponding log-reduction and BCR-ABL1 transcript levels on the International Scale. The molecular response milestones to which TKI therapy currently aims are indicated.

Levels of molecular response and corresponding log-reduction and BCR-ABL1 transcript levels on the International Scale. The molecular response milestones to which TKI therapy currently aims are indicated.

For almost 10 years, the main goal of the treatment of CML with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has been the achievement of the so-called “major molecular response” (MMR; BCR-ABL1 ≤ 0.1% on the International Scale)2 (see figure). Then, the main focus shifted to the so-called “early molecular response” (EMR; BCR-ABL1 ≤ 10% at 3 months) as a predictor of a deeper response and of a better outcome.2 Branford et al report that a dynamic evaluation of EMR may have a greater prognostic value than the value of a single assessment at 3 months. They analyzed 507 consecutive adult patients with newly diagnosed, chronic phase CML. They confirmed that the patients (n = 97, 18%) who did not achieve the 10% level at 3 months had a poorer 4-year progression-free survival (PFS; 86% vs 99%) and overall survival (OS; 87% vs 97%) and were less likely to achieve an MMR and a deeper molecular response. However, they found that the rate of BCR-ABL1 decline from individual patient baseline over the first 3 months—assessed by estimating the number of days over which BCR-ABL1 halved—more precisely identified a subset of very poor EMRs. Of 95 patients with >10% BCR-ABL1 at 3 months, 74 (78%) had a rapid decline of transcripts level (≥50% in ≤76 days), whereas 21 (22%) had a slow or no decline. The former had a 4-year PFS (92%) and OS (95%) similar to the patients who had achieved the 10% response at 3 months, whereas only the latter had a significantly poorer outcome (PFS, 63%; OS, 58%) and a significantly lower probability of achieving an MMR (only 5% vs 54%). The conclusion is that measuring the rate of the decline is more important than a single test and better selects the poor EMRs.

The study by Branford et al was presented at the last 2013 meeting of the American Society of Hematology. At the same meeting, a similar study was presented by the German CML Study Group and is now in press.3 This study reported on 301 patients in which the individual velocity of transcripts elimination was calculated. In the 48 patients (16% of total) with <0.35-fold decrease in 3 months, 5-year PFS and OS were inferior (77% vs 96% and 83% vs 98%, respectively).3 Are these 2 studies, coming from institutions that have marked the progress in CML therapy, sufficient to dismiss the prognostic value of the 3-month EMR (BCR-ABL1 ≤10% vs >10%) that has been introduced and confirmed by several recent studies?4-9 Logic would say yes—because any phenomenon, in this case the response, is better defined by three points and a line rather than by a single point. Moreover, a more precise identification of the truly poor responders would limit the indication to an early therapy switch, with both a clinical and a financial benefit. However, it should not be overlooked that the Australian study reported on patients treated first line with different imatinib doses (400, 600, and 800 mg), as it was also the case in the German study—where patients treated with imatinib plus interferon-α were also included.

It is unclear whether, and to what extent, the rate and amount of decline of BCR-ABL1 would prove to be significant in patients treated with a standard imatinib dose (400 mg) or with second-generation TKIs. Moreover, methodological and standardization problems are of concern, because to measure the decline of BCR-ABL1 transcripts in individual patients, the control gene cannot be ABL1 (the most commonly used worldwide), but must be BCR2 or β-glucuronidase (GUS).4

These new findings will add fuel to an already hot controversy concerning if and when to change the first-line TKI.1-10 Whatever the definition of EMR, we do not yet know whether an early switch from imatinib to a second-generation TKI would be of benefit, and if so, to what extent. A benefit can be expected,10 but the expectation should be supported by data that are still missing.1 In addition, how many patients would take advantage of a TKI change, if the dynamic evaluation of EMR selected a very poor responder subset? Would such patients require another TKI or rather allogeneic stem cell transplantation? Prospective studies will be needed. Nevertheless, one message is clear—that to further improve a treatment that is already excellent, not only new drugs, but also more careful and frequent monitoring, are required. The cost of a real-time polymerase chain reaction test is approximately the same as the cost of 1 day of TKI treatment. More frequent monitoring, as suggested by Branford et al, helps to optimize both treatment results and the use of financial resources.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.B. has received honoraria as a consultant, an advisor, and a lecturer from Ariad, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis Pharma, and Pfizer. S.S. has received honoraria as a consultant and a lecturer from Ariad, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis Pharma.