Key Points

JAK2R564Q is the first germline JAK2 mutation found to contribute to a familial MPN that involves a residue other than V617.

The kinase activity of JAK2R564Q and JAK2V617F are the same, but only V617F is able to escape regulation by SOCS3 and p27.

Along with the most common mutation, JAK2V617F, several other acquired JAK2 mutations have now been shown to contribute to the pathogenesis of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs). However, here we describe for the first time a germline mutation that leads to familial thrombocytosis that involves a residue other than Val617. The novel mutation JAK2R564Q, identified in a family with autosomal dominant essential thrombocythemia, increased cell growth resulting from suppression of apoptosis in Ba/F3-MPL cells. Although JAK2R564Q and JAK2V617F have similar levels of increased kinase activity, the growth-promoting effects of JAK2R564Q are much milder than those of JAK2V617F because of at least 2 counterregulatory mechanisms. Whereas JAK2V617F can escape regulation by the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 and p27/Kip1, JAK2R564Q-expressing cells cannot. Moreover, JAK2R564Q-expressing cells are much more sensitive to the JAK inhibitor, ruxolitinib, than JAK2V617F-expressers, suggesting that lower doses of this drug may be effective in treating patients with MPNs associated with alternative JAK2 mutations, allowing many undesirable adverse effects to be avoided. This work provides a greater understanding of the cellular effects of a non-JAK2V617F, MPN-associated JAK2 mutation; provides insights into new treatment strategies for such patients; and describes the first case of familial thrombosis caused by a JAK2 residue other than Val617.

Introduction

The discovery that the acquired JAK2 mutation, JAK2V617F, contributes to the Philadelphia chromosome-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) significantly advanced our understanding of these diseases.1,-3 We now know that this mutation in the pseudokinase domain of JAK2 contributes to the origins of about half of all patients with acquired essential thrombocythemia (ET) and primary myelofibrosis (PMF) and nearly all patients with acquired polycythemia vera (PV).4,-6 More recently, other mutations, deletions, or insertions in JAK2,7,-9 MPL,10,11 KIT,12 TET2,13,14 and SH2B3, which encodes LNK,15 have all been shown to contribute to the development of MPNs.

The JAK2 protein is comprised of a 4-point, ezrin, radixin, moesin (FERM) domain at the N terminus, followed by a SRC homology 2 (SH2)-like domain, a JAK homology 2 (JH2) pseudokinase domain, and a JH1 active tyrosine kinase domain (Figure 1E). Occurring in the pseudokinase domain, the crystal structure of which has recently been published,16 the JAK2V617F mutation is commonly thought to interrupt autoinhibitory interactions that would normally facilitate inhibition of the JH1 kinase activity by the JH2 pseudokinase domain. This acquired somatic mutation occurs at the level of the hematopoietic stem cell, giving rise to lineage-specific cells that are hypersensitive to cytokine stimulation. Several mechanisms have been reported to be responsible for mediating these effects. JAK2V617F downregulates p27/Kip1, a cell cycle inhibitor at the G1 to S transition. Direct phosphorylation of p27/Kip1 by JAK2V617F impairs its ability to inhibit the growth-promoting cell cycle kinase Cdk and marks it for proteasomal degradation.17 Activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) by JAK2V617F also leads to increased transcription of Skp2, a subunit of ubiquitin E3 ligase, which further promotes p27/Kip1 degradation.18,19 Moreover, the normal control on overexuberant cell growth, mediated by the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), which acts to regulate JAK2 activity, is also abrogated by JAK2V617F in BaF/3 cells.20 SOCS3 expression, induced several hours after the onset of JAK/STAT signaling, inhibits JAK2 activity either through direct binding to the JH1 catalytic loop or through generation of an E3 ligase that ubiquitinates JAK2 and targets it for degradation. However, in BaF/3 cells, SOCS3 is unable to regulate JAK2V617F and, paradoxically, enhances its activity.20 This effect may be context-dependent, however, as it has also been reported that SOCS3 can inhibit JAK2V617F signaling through proteasomal degradation in HEK cells.21

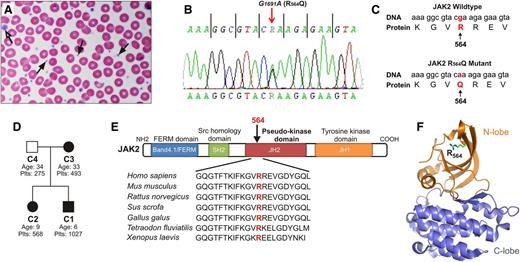

Patient with JAK2R564Q mutation displays MPN. (A) Examination of the index patient's blood smear revealed increased platelet number. Platelet morphology and granulation were normal, and most platelets were of normal size (black arrows). Rarely, however, giant platelets were observed (open arrow). (B) Sequence analysis revealed a novel G-to-A single-point mutation in JAK2 at nucleotide 1691, causing an amino acid substitution of arginine for glutamine at position 564 (C). (D) Pedigree of the studied ET family. Squares represent males, circles represent females. JAK2R564Q-positive family members are shown in black, and the JAK2R564Q-negative member in white. Plts indicates platelet counts of each family member (×103/μL). (E) Alignment of JAK2 sequences from different species shows that the arginine at position 564 in the pseudokinase domain is highly conserved. (F) Three-dimensional model of the JAK2 JH2 pseudokinase domain based on Bandaranayake et al16 with the N lobe colored orange and the C lobe colored blue. Arginine 564 (R564) is located in the 5 stranded β sheet of the N lobe.

Patient with JAK2R564Q mutation displays MPN. (A) Examination of the index patient's blood smear revealed increased platelet number. Platelet morphology and granulation were normal, and most platelets were of normal size (black arrows). Rarely, however, giant platelets were observed (open arrow). (B) Sequence analysis revealed a novel G-to-A single-point mutation in JAK2 at nucleotide 1691, causing an amino acid substitution of arginine for glutamine at position 564 (C). (D) Pedigree of the studied ET family. Squares represent males, circles represent females. JAK2R564Q-positive family members are shown in black, and the JAK2R564Q-negative member in white. Plts indicates platelet counts of each family member (×103/μL). (E) Alignment of JAK2 sequences from different species shows that the arginine at position 564 in the pseudokinase domain is highly conserved. (F) Three-dimensional model of the JAK2 JH2 pseudokinase domain based on Bandaranayake et al16 with the N lobe colored orange and the C lobe colored blue. Arginine 564 (R564) is located in the 5 stranded β sheet of the N lobe.

Although JAK2V617F in exon 14 is the most common mutation of JAK2 associated with MPNs, insertion/deletion events in JAK2 exon 12 are also known contributors.8,9 A screening of blood samples from suspected MPN patients revealed further point mutations in exons 12 to 15,7 although functional studies to confirm their contribution to disease pathogenesis have yet not been performed for many of these mutant kinases. Thus far, nearly every previously identified JAK2 alteration found in patients with MPNs, including JAK2V617F, are somatic, acquired mutations. The single exception is JAK2V617I, recently proposed as a germline mutation associated with hereditary thrombocytosis.22,23 Here we describe for the first time a JAK2 mutation associated with a familial MPN that involves a residue other than Val617. This novel mutation in exon 13 of JAK2 is a single nucleotide substitution, g1691a, which results in an arginine to glutamine change at position 564 (JAK2R564Q). This mutation, present in 3 of 4 of the studied family members, is associated with hereditary thrombocytosis and increased JAK2 activation in platelets. We have further shown that in cell lines, the mutation leads to JAK2 hypersensitivity and increased cell growth resulting from suppression of apoptosis. Despite being localized in the same pseudokinase domain as V617 and generating similar levels of increased JAK2 activity, the effects of JAK2R564Q are distinct from those of JAK2V617F. Similar to the wild-type (WT) kinase, proliferation of JAK2R564Q-Ba/F3-MPL cells is regulated by the cell cycle inhibitor, p27/Kip1, whereas JAK2V617F is able to decrease p27/Kip1 levels and escape this regulation. Furthermore, SOCS3 negatively regulates JAK2R564Q, as for WT kinase but is unable to inhibit JAK2V617F. Finally, we show that the JAK inhibitor, ruxolitinib, is able to effectively reduce the cell growth associated with JAK2R564Q-expressing cells, and much lower concentrations are required than those needed to generate the same effect in JAK2V617F-expressing cells. This work describes the first reported case of familial thrombocytosis caused by a JAK2 mutation other than at position V617, provides valuable insights into the cellular effects of alternative MPN-associated JAK2 mutations, and has clear clinical implications for the treatment of the MPNs arising in mutations other than JAK2V617F.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

Written informed consent was obtained from patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with approval from the Stony Brook University Ethics Committee. X-chromosome inactivation pattern (XCIP) experiments were performed on patient myeloid cells according to Pan and Peng24 and were analyzed on 3% agarose gels. Platelet lysate collection and all other methods are described in the methods section of the supplemental data, found on the Blood Web site.

Results

Case presentation and generation of JAK2R564Q cell lines

A 6-year-old boy with a prolonged, elevated platelet count (800-1300 ×103/µL, monitored over the course of 3 years) who was negative for secondary thrombocytosis such as iron deficiency and inflammatory diseases was diagnosed with ET (the patient was designated C1; Table 1). A blood smear further confirmed an increased platelet number (Figure 1A). Evaluation of the patient for MPN revealed a normal breakpoint cluster region-abelson (BCR-ABL) PCR test and a normal karyotype, 46XY, and assessments for JAK2V617F, MPLW515, and S505 mutations were negative. However, sequence analysis revealed a novel JAK2 G-to-A mutation at nucleotide 1691 in exon 13 (Figure 1B), resulting in an amino acid substitution of arginine to glutamine at position 564 (JAK2R564Q; Figure 1C). In addition, the patient’s sister (C2) and mother (C3) were also thrombocytotic (500-600 ×103/µL platelet counts), and both tested positive for the JAK2R564Q mutation (Figure 1D; Table 1). The father (C4), however, had platelet counts in the normal range and was negative for JAK2R564Q.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the ET family

| Characteristics . | C1 Son . | C2 Daughter . | C3 Mother . | C4 Father . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 6 | 9 | 33 | 34 |

| Sex | Male | Female | Female | Male |

| Palpable splenomegaly | No | No | No | No |

| History of thrombosis | No | No | No | No |

| History of hemorrhage | No | No | No | No |

| WBC count (×103/µL) | 10.2 | 10.2 | 9.2 | 8.1 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.2 | 13.0 | 13.2 | 14.6 |

| Platelet count (×103/µL) | 1027 | 568 | 493 | 275 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 68 | — | — | — |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 6 | 2 | — | — |

| Cytogenetics | 46, XY | — | — | — |

| Peripheral blood BCR-ABL PCR | Negative | — | — | — |

| JAK2 mutations | ||||

| V617F | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| R564Q | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| MPL mutations | ||||

| W515 | Negative | — | — | — |

| S505 | Negative | — | — | — |

| Characteristics . | C1 Son . | C2 Daughter . | C3 Mother . | C4 Father . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 6 | 9 | 33 | 34 |

| Sex | Male | Female | Female | Male |

| Palpable splenomegaly | No | No | No | No |

| History of thrombosis | No | No | No | No |

| History of hemorrhage | No | No | No | No |

| WBC count (×103/µL) | 10.2 | 10.2 | 9.2 | 8.1 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.2 | 13.0 | 13.2 | 14.6 |

| Platelet count (×103/µL) | 1027 | 568 | 493 | 275 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 68 | — | — | — |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 6 | 2 | — | — |

| Cytogenetics | 46, XY | — | — | — |

| Peripheral blood BCR-ABL PCR | Negative | — | — | — |

| JAK2 mutations | ||||

| V617F | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| R564Q | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| MPL mutations | ||||

| W515 | Negative | — | — | — |

| S505 | Negative | — | — | — |

XCIP analysis was performed on myeloid cells from the 2 JAK2R564Q-positive female patients (C2 and C3) to assess clonality in hematopoietic cells. A polyclonal pattern with 57% expression of a single allele was seen in C2, indicating that the JAK2R564Q mutation may be sufficient to drive the thrombocytosis without the acquisition of additional somatic mutations. C3 showed 90% expression of the predominant allele, suggesting myeloid clonality and the possibility that an additional somatic mutation may be contributing to the mild thrombocytosis of this patient. Given the limitations of the assay,25 and without determining clonality in T-cell controls, it is difficult to accurately interpret this imbalanced pattern.

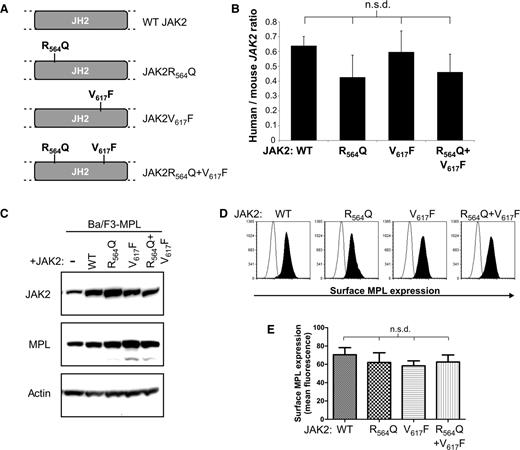

R564 is very highly conserved across species (Figure 1E). It is located in the JH2 pseudokinase domain (Figure 1F), along with the well-characterized JAK2V617F mutation. To determine the functional consequences of JAK2R564Q and compare them with those of JAK2V617F, we generated 4 cell lines expressing WT and mutated forms of human JAK2 (Figure 2A). We previously generated a Ba/F3 cell line, which stably expresses the human thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor c-MPL (Ba/F3-MPL).26 A single Ba/F3-MPL clone was further transfected with 1 of 4 forms of JAK2: WT JAK2, JAK2R564Q, JAK2V617F, and finally a double mutant, JAK2R564Q and V617F, to generate stably expressing pools. The double mutant was studied alongside the 2 single mutants to test whether the effects of the mutations were additive to determine whether distinct or similar mechanisms are used by each mutant. Because no commercially available antibodies can distinguish between human and murine JAK2, expression of human JAK2 mRNA was verified by real-time PCR, using specific primers. Levels of human JAK2 cDNA, normalized by endogenous mouse Jak2 cDNA levels, were quantified, and no significant difference was observed between the 4 cell lines (Figure 2B). Similar levels of both total JAK2 and MPL protein were determined in all 4 cell lines by western blot analysis (Figure 2C). Cell surface expression of MPL was also measured by flow cytometry (Figure 2D), and no significant difference in cell surface MPL expression was found between the cell lines (Figure 2E).

JAK2 mutant Ba/F3-MPL cell line generation. (A) Ba/F3 cell lines that stably express Mpl (BaF-MPL) and 1 of 4 types of human JAK2 (WTJAK2, JAK2R564Q, JAK2V617F, and both JAK2R564Q and JAK2V617F) were generated. (B) No significant difference (n.s.d) is seen in levels of human/mouse JAK2 cDNA levels between the 4 cell lines, measured by real-time PCR. (C) Western blot analysis of total JAK2 and total MPL levels in each of the 4 mutant cell lines compared with Ba/F3-MPL parental cells (first lane from left). (D-E) Cell surface expression of MPL in the Ba/F3-MPL-JAK2 cell lines, analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Examples of overlays of the surface MPL flow cytometry of stained cells (black peak) compared with BaF3 parental controls (unfilled peak) for all 4 cell lines. (E) Histogram representing the combined flow cytometric data from all 3 repeats. No significant difference (n.s.d.) in surface MPL expression was found between the 4 cell lines.

JAK2 mutant Ba/F3-MPL cell line generation. (A) Ba/F3 cell lines that stably express Mpl (BaF-MPL) and 1 of 4 types of human JAK2 (WTJAK2, JAK2R564Q, JAK2V617F, and both JAK2R564Q and JAK2V617F) were generated. (B) No significant difference (n.s.d) is seen in levels of human/mouse JAK2 cDNA levels between the 4 cell lines, measured by real-time PCR. (C) Western blot analysis of total JAK2 and total MPL levels in each of the 4 mutant cell lines compared with Ba/F3-MPL parental cells (first lane from left). (D-E) Cell surface expression of MPL in the Ba/F3-MPL-JAK2 cell lines, analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Examples of overlays of the surface MPL flow cytometry of stained cells (black peak) compared with BaF3 parental controls (unfilled peak) for all 4 cell lines. (E) Histogram representing the combined flow cytometric data from all 3 repeats. No significant difference (n.s.d.) in surface MPL expression was found between the 4 cell lines.

Expression of JAK2R564Q causes increased intracellular signaling

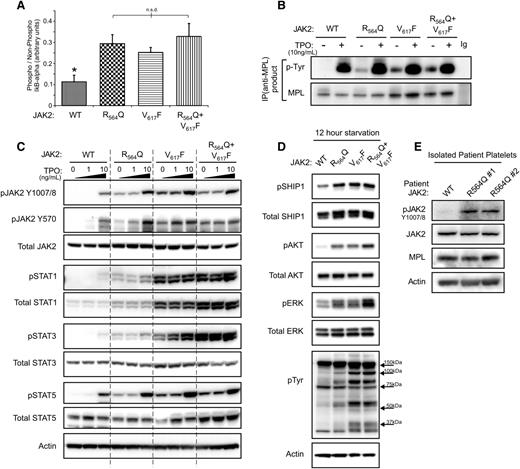

To begin to understand the contribution of JAK2R564Q to the pathogenesis of familial thrombocytosis, we determined the effects of the mutation on JAK2 activity and signaling. The kinase activity of JAK2, JAK2R564Q, JAK2V617F, and the combined mutant kinase were assessed using an in vitro kinase assay (Figure 3A). All 3 mutant forms of JAK2 showed a similar, approximately threefold increase in activity compared with WT. However, there were no significant differences in kinase activity between each of the JAK2 mutants. To confirm the ability of the mutant JAK2s to phosphorylate MPL, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-MPL antibody before probing with an anti-phospho-Tyrosine antibody (Figure 3B). In the absence of TPO, no phosphorylated MPL was observed in WT JAK2 cells, although MPL was phosphorylated in JAK2R564Q, JAK2V617F and the double mutant cells. As expected from the kinase activity results, we confirmed an increase in the levels of the positive regulator, phosphorylated JAK2Tyr1007/8 in both JAK2R564Q- and JAK2V617F-expressing mutants compared with WT in the absence of, and at 1 ng/mL and 10 ng/mL, TPO (Figure 3C). However, we also observed increased phosphorylation of the negative regulatory site JAK2Tyr570, suggesting a general global increase in JAK2 tyrosine phosphorylation. Phosphorylated levels of the downstream signaling proteins STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 were elevated in each of the mutant JAK2 cell lines, especially in the absence of TPO (Figure 3C). We also found higher levels of pSTAT1 and pSTAT3 in cells expressing JAK2V617F compared with JAK2R564Q. Total STAT1 levels were also increased with JAK2R564Q expression compared with WTJAK2, and this effect was even more prominent with JAK2V617F. An overall increase in downstream signaling in mutant JAK2 cells under starved conditions was further demonstrated (Figure 3D). Tyrosine-phosphorylation of proteins was also upregulated in JAK2R564Q-expressing cells compared with WTJAK2, and this was even more robust in the JAK2V617F-expressing mutants (Figure 3D). Furthermore, similar increased signaling was observed in JAK2R564Q-positive patients (Figure 3E). Platelets were isolated from 3 members of the family with the JAK2R564Q mutation and subject to western blot analysis. Phosphorylation of JAK2 was increased in the JAK2R564Q-positive family members (R564Q1 and R564Q2) compared with the father, who is negative for the mutation (WT).

Expression of JAK2R564Q causes increased intracellular signaling in cell lines and patients. (A) JAK2 activity determined by in vitro kinase assay, based on the ability of the kinase to phosphorylate an IκB-α substrate. (B) After starvation overnight and treatment with/without 10 ng/mL TPO for 5 minutes, cells were lysed and proteins subject to MPL pull-down and western blotting with p-Tyr probe to show levels of phosphorylated MPL in the cell lines. In the absence of TPO, MPL is not phosphorylated by WTJAK2 but is phosphorylated by each of the 3 JAK2 mutants. (C) After starvation overnight, western blot analysis shows increased levels of phosphorylated JAK2 and STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 in the mutant cell lines, in the absence of, and at low concentrations of TPO treatment of 5 minutes. (D) Western blot analysis of the phosphorylation status of signaling proteins downstream of JAK2 in starved conditions. (E) Platelets were isolated from 3 members of the family with JAK2R564Q mutation and subject to western blot analysis.

Expression of JAK2R564Q causes increased intracellular signaling in cell lines and patients. (A) JAK2 activity determined by in vitro kinase assay, based on the ability of the kinase to phosphorylate an IκB-α substrate. (B) After starvation overnight and treatment with/without 10 ng/mL TPO for 5 minutes, cells were lysed and proteins subject to MPL pull-down and western blotting with p-Tyr probe to show levels of phosphorylated MPL in the cell lines. In the absence of TPO, MPL is not phosphorylated by WTJAK2 but is phosphorylated by each of the 3 JAK2 mutants. (C) After starvation overnight, western blot analysis shows increased levels of phosphorylated JAK2 and STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 in the mutant cell lines, in the absence of, and at low concentrations of TPO treatment of 5 minutes. (D) Western blot analysis of the phosphorylation status of signaling proteins downstream of JAK2 in starved conditions. (E) Platelets were isolated from 3 members of the family with JAK2R564Q mutation and subject to western blot analysis.

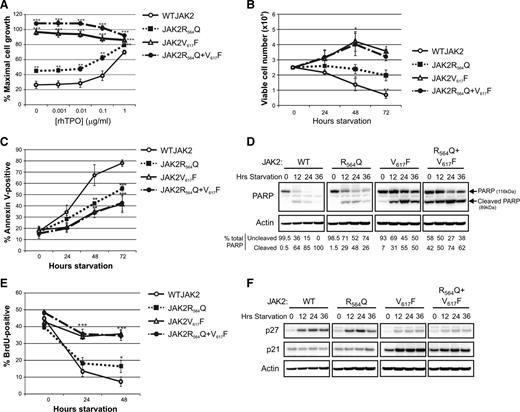

JAK2R564Q-expressing cells exhibit reduced cell growth compared with JAK2V617F-expressing cells in the absence of cytokine

The growth characteristics of the JAK2-expressing cell lines in response to TPO treatment were then determined using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dimethyltetrazolium bromide assays. Cells expressing JAK2V617F, either with or without JAK2R564Q, were factor-independent, and proliferation was significantly increased from WTJAK2-expressing cells in the absence of, and at all concentrations of, TPO (Figure 4A). JAK2R564Q-expressing cells also showed significantly increased proliferation compared with WTJAK2 cells, although cell proliferation was much less striking than with JAK2V617F and was still responsive to cytokine stimulation (Figure 4A). We hypothesized that the mild hyperproliferative phenotype of JAK2R564Q cells compared with WT controls was possibly a result of a decrease in apoptosis in the absence of, or at low concentrations of, TPO.

JAK2R564Q-expressing cells exhibit increased cell growth with a pronounced antiapoptotic effect and a mild proliferative effect. (A) 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dimethyltetrazolium bromide assay to measure proliferation in the 4 mutant JAK2 cell lines with increasing TPO concentration under starved conditions. Each data point is expressed as a percentage of proliferation stimulated by a maximal dose of murine interleukin 3 and represents 6 repeats. All mutant JAK2-expressing cells show significantly increased proliferation compared with WTJAK2-expressing cells in the absence of, and at all concentrations of, TPO. **P < .01; ***P < .001. (B) Viable cell counts every 24 hours under starved conditions, for a total of 72 hours. Data shown are from 3 independent repeats. JAK2V617F and double-mutant cells are able to proliferate in the absence of cytokine and show a significant increase in cell number, compared with 0 hours, at both 48 and 72 hours (*P < .05). The number of viable WTJAK2-expressing cells, compared with starting number, was significantly decreased at all points (*P < .05; **P < .01). No significant difference was seen in the number of viable JAK2R564Q cells, compared with the starting number, for the 72-hour period. (C) Apoptosis measured by Annexin V staining of cells under starved conditions for 72 hours. By 48 hours, the number of apoptotic cells in the mutant JAK2 cell lines was significantly less than the number of WTJAK2-expressing apoptotic cells. (D) Western blot analysis over 36 hours of starvation demonstrates increased levels of uncleaved PARP in all 3 of the JAK2 mutants compared with WTJAK2. (E) BrdU assay to measure proliferation during 48 hours of starvation. Proliferation in both WTJAK2 and JAK2R564Q cells decreased during the 48-hour period, although proliferation in JAK2R564Q cells was significantly increased compared with WTJAK2 controls after 48 hours (*P < .05). Proliferation continued in the cell lines with the JAK2V617F mutation, however, and the percentage of BrdU-positive cells in these cell lines was significantly more than in the WTJAK2 controls after both 24 and 48 hours (***P < .001). (F) Western blot analysis during starved conditions showed an increase in p27/Kip1 protein levels during the starvation period in the WTJAK2 and JAK2R564Q cell lines. p27/Kip1 levels were much reduced in the JAK2V617F-expressing mutants, however. p21CIP/WAF1 levels remained fairly constant in each cell line throughout the starvation period.

JAK2R564Q-expressing cells exhibit increased cell growth with a pronounced antiapoptotic effect and a mild proliferative effect. (A) 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dimethyltetrazolium bromide assay to measure proliferation in the 4 mutant JAK2 cell lines with increasing TPO concentration under starved conditions. Each data point is expressed as a percentage of proliferation stimulated by a maximal dose of murine interleukin 3 and represents 6 repeats. All mutant JAK2-expressing cells show significantly increased proliferation compared with WTJAK2-expressing cells in the absence of, and at all concentrations of, TPO. **P < .01; ***P < .001. (B) Viable cell counts every 24 hours under starved conditions, for a total of 72 hours. Data shown are from 3 independent repeats. JAK2V617F and double-mutant cells are able to proliferate in the absence of cytokine and show a significant increase in cell number, compared with 0 hours, at both 48 and 72 hours (*P < .05). The number of viable WTJAK2-expressing cells, compared with starting number, was significantly decreased at all points (*P < .05; **P < .01). No significant difference was seen in the number of viable JAK2R564Q cells, compared with the starting number, for the 72-hour period. (C) Apoptosis measured by Annexin V staining of cells under starved conditions for 72 hours. By 48 hours, the number of apoptotic cells in the mutant JAK2 cell lines was significantly less than the number of WTJAK2-expressing apoptotic cells. (D) Western blot analysis over 36 hours of starvation demonstrates increased levels of uncleaved PARP in all 3 of the JAK2 mutants compared with WTJAK2. (E) BrdU assay to measure proliferation during 48 hours of starvation. Proliferation in both WTJAK2 and JAK2R564Q cells decreased during the 48-hour period, although proliferation in JAK2R564Q cells was significantly increased compared with WTJAK2 controls after 48 hours (*P < .05). Proliferation continued in the cell lines with the JAK2V617F mutation, however, and the percentage of BrdU-positive cells in these cell lines was significantly more than in the WTJAK2 controls after both 24 and 48 hours (***P < .001). (F) Western blot analysis during starved conditions showed an increase in p27/Kip1 protein levels during the starvation period in the WTJAK2 and JAK2R564Q cell lines. p27/Kip1 levels were much reduced in the JAK2V617F-expressing mutants, however. p21CIP/WAF1 levels remained fairly constant in each cell line throughout the starvation period.

To test this hypothesis, cells were grown in the absence of cytokine, and viable cells were counted every 24 hours (Figure 4B). Viable cell number dropped significantly even after only 24 hours in WTJAK2-expressing cells, whereas a significant increase was seen in the number of cells expressing JAK2V617F, confirming their factor independence. However, the JAK2R564Q-expressing cells exhibited no significant change in cell number during the 72-hour period. These data indicate that although the JAK2R564Q mutation may not stimulate cell proliferation in the absence of cytokine, it inhibits apoptosis.

To confirm this finding, after cytokine starvation we determined the percentage of apoptotic cells every 24 hours by annexin V staining (Figure 4C). The vast majority of WT cells were apoptotic by 48 hours of starvation (approximately 70%), whereas the number of apoptotic cells in JAK2V617F-expressing cell lines was significantly less (approximately 35%). Supporting our previous results, apoptosis was attenuated in JAK2R564Q-positive cells (approximately 42% after 48 hours). Concurrent with these findings, higher levels of uncleaved poly ADP ribose polymerase with prolonged starvation were also observed in cells expressing JAK2R564Q, compared with WTJAK2, by western blot (Figure 4D). However, levels of uncleaved PARP were even higher in the JAK2V617F and double mutants.

Next, we determined whether any of the cell lines were able to proliferate in the absence of cytokine using 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) assays (Figure 4E). JAK2R564Q exhibited only a modest increase in the number of cycling cells compared with control and only after 48 hours. Cell lines with the JAK2V617F mutation, however, continued to actively proliferate for the entire 48 hours, with only a slight decrease compared with cells grown with cytokine. Expression of cell cycle regulators was further examined (Figure 4F). Levels of p27/Kip1, the negative regulator of the G1 to S phase transition, increased in both WTJAK2 and JAK2R564Q-expressing cells with prolonged starvation. However, p27/Kip1 levels remained low in the JAK2V617F-expressing cells throughout the 36-hour period, suggesting a mechanism by which proliferation might be enhanced in these cells compared with those expressing JAK2R564Q. p21/CIP/WAF1 levels remained constant in WTJAK2 and JAK2R564Q-expressing cells throughout the 36-hour period, although they were increased after 12 hours in the JAK2V617F-expressing cells. As p21 is also a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, it may be involved in negative feedback to inhibit JAK2V617F cell proliferation. However, if the effects of p21 are less potent than those of p27, this may explain the differences in proliferation. Therefore, we concluded that the differences in cell cycle behavior between JAK2V617F- and JAK2R564Q-expressing cells were accounted for by p27, and not p21. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that the JAK2R564Q mutation is able to inhibit apoptosis in the absence of cytokines but does not stimulate proliferation.

To determine whether JAK2R564Q can also signal through the erythropoietin receptor (EPOR), rather than MPL, we generated a Ba/F3 cell line that stably expresses the human EPOR (Ba/F3-EPOR) and then further transfected a single Ba/F3-EPOR clone with WTJAK2, JAK2R564Q, or JAK2V617F. Each of the cell lines showed similar levels of both total JAK2 and EPOR (supplemental Figure 1A). As shown by others,1 JAK2V617F-expression was still able to increase cell growth in Ba/F3-EPOR cells compared with WTJAK2 (supplemental Figure 1B). However, JAK2R564Q expression had no effect on cell growth compared with WTJAK2, despite causing a modest increase in the phosphorylation of signaling proteins (supplemental Figure 1C). Therefore, it appears that JAK2R564Q can only exert its proliferation-enhancing effects by signaling through MPL, and not EPOR.

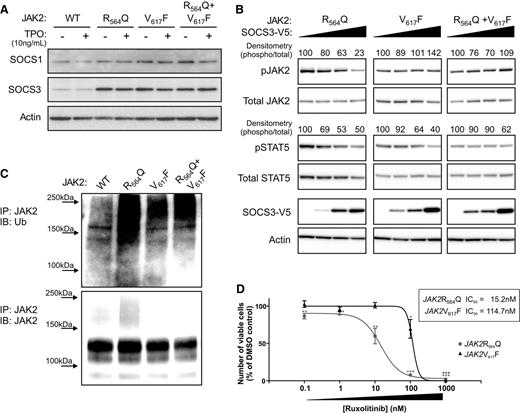

JAK2R564Q is negatively regulated by SOCS3 overexpression

SOCS proteins negatively regulate JAK2 activity, either through direct inhibition or by stimulating the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the kinase. To explore whether SOCS proteins might also account for the differences in cell proliferation between JAK2V617F and JAK2R564Q in BaF-MPL cells, we next determined the endogenous levels of SOCS1 and SOCS3 in the JAK2-expressing cell lines by western blot analysis (Figure 5A). Although SOCS1 expression was largely unaltered between WT and the mutant JAK2-expressing cell lines, SOCS3 levels were increased in all cell lines expressing mutant JAK2 compared with WT JAK2, both with and without TPO stimulation. Therefore, we next investigated the effect of SOCS3 overexpression in these cells (Figure 5B). In JAK2R564Q-expressing cells, the increased concentration of SOCS3 was associated with a decrease in pJAK2. However, this negative feedback was not observed in the JAK2V617F-expressing cells, where pJAK2 levels remained unaltered. Furthermore, we observed more ubiquitinated JAK2 in starved JAK2R564Q-expressing cells compared with starved WTJAK2-expressing cells, as there are more cells still proliferating in the absence of cytokine, and therefore presumably more stimulation of the negative feedback mechanism to unbiquitinate JAK2 and target it for proteasomal degradation (Figure 5C). Conversely, although JAK2V617F-expressing cells also proliferate more robustly than WTJAK2-expressing cells, in the absence of cytokine, ubiquitination levels of JAK2 were much lower in the JAK2V617F-bearing cells compared with those expressing JAK2R564Q. This may be the result of an escape of the negative regulation by JAK2V617F, so that it is not ubiquitinylated for degradation in response to proliferation.

JAK2R564Q is negatively regulated by SOCS3 overexpression and is more sensitive to the JAK2 inhibitor, ruxolitinib, than JAK2V617F. (A) Endogenous levels of SOCS1 and SOCS3 in the JAK2 cell lines, with and without TPO stimulation, shown by western blot. (B) Western blot analysis of protein levels in the JAK2-expressing cells transiently transfected with increasing concentrations of SOCS3 for 24 hours and then starved for a following 4 hours. Numbers represent densitometric quantification of phosphorylated protein levels. (C) JAK2 immunoprecipitation and ubiquitin probe by western blot, after starvation. (D) Cells were grown under starved conditions in the presence of 0 to 1 μM ruxolitinib, a JAK inhibitor. After 48 hours, the number of viable cells was measured as a percentage of the dimethylsulfoxide control. A significant decrease in cell viability, compared with dimethylsulfoxide control, was observed in JAK2R564Q-expressing cells at concentrations of 0.1 nM ruxolitinib and above, whereas cell viability only significantly dropped, compared with the control, in the cells expressing JAK2V617F, with 100 nM and 1 μM ruxolitinib treatment. The IC50 value of JAK2R564Q (15.2 nM) was almost 8 times lower than that of JAK2V617F (114.7 nM).

JAK2R564Q is negatively regulated by SOCS3 overexpression and is more sensitive to the JAK2 inhibitor, ruxolitinib, than JAK2V617F. (A) Endogenous levels of SOCS1 and SOCS3 in the JAK2 cell lines, with and without TPO stimulation, shown by western blot. (B) Western blot analysis of protein levels in the JAK2-expressing cells transiently transfected with increasing concentrations of SOCS3 for 24 hours and then starved for a following 4 hours. Numbers represent densitometric quantification of phosphorylated protein levels. (C) JAK2 immunoprecipitation and ubiquitin probe by western blot, after starvation. (D) Cells were grown under starved conditions in the presence of 0 to 1 μM ruxolitinib, a JAK inhibitor. After 48 hours, the number of viable cells was measured as a percentage of the dimethylsulfoxide control. A significant decrease in cell viability, compared with dimethylsulfoxide control, was observed in JAK2R564Q-expressing cells at concentrations of 0.1 nM ruxolitinib and above, whereas cell viability only significantly dropped, compared with the control, in the cells expressing JAK2V617F, with 100 nM and 1 μM ruxolitinib treatment. The IC50 value of JAK2R564Q (15.2 nM) was almost 8 times lower than that of JAK2V617F (114.7 nM).

JAK2R564Q is more sensitive to ruxolitinib than JAK2V617F

Finally, to determine whether any or all of these cellular differences might affect clinical responses to therapeutic JAK inhibition, we used a commercially available JAK inhibitor, ruxolitinib (Jakafi; Incyte Corporation), to observe the effects of inhibiting JAK activity in mutant JAK2-expressing cells (Figure 5D). Viable cell number was measured after incubation in increasing concentrations of ruxolitinib under starved conditions. The number of viable cells was significantly decreased by concentrations of 100 nM ruxolitinib (P < .05) and above in the JAK2V617F-expressing cell line. However, a significant decrease in cell viability, compared with dimethylsulfoxide controls, was seen in the presence of only 0.1 nM ruxolitinib (P < .01) in JAK2R564Q-expressing cells, and viability continued to decrease as the concentration of the JAK inhibitor was raised. The 50% inhibition/inhibitory concentration (IC50) value for JAK2R564Q (15.2 nM) was approximately 8 times lower than the IC50 value for JAK2V617F (114.7 nM).

Discussion

Here we describe a novel, autosomal dominant mutation that causes familial ET resulting from a single nucleotide substitution, generating the mutant kinase JAK2R564Q. MPNs are commonly associated with somatic mutations acquired by individuals, which disrupt regulation of JAK2 signaling. To date, only a single other inherited JAK2 mutation has been suggested to be responsible for the development of MPN,22,23 and this involved an Ile substitution of the well-studied Val617 residue. Here we describe a novel germline mutation of JAK2 associated with familial ET that does not involve Val617 but, rather, an alternative residue in the same JH2 domain, Arg564. Our data indicate that this mutation may be sufficient to drive thrombocytosis. The phenotype appears highly penetrant and is observed in young family members; screening for other known MPN-associated mutations proved negative, and mild thrombocytosis was observed despite myeloid polyclonality, shown by XCIP analysis in a female family member. Furthermore, increased activation of JAK2 was confirmed in the platelets of JAK2R564Q-positive family members compared with those without the mutation.

To elucidate the cellular effects of JAK2R564Q, we generated Ba/F3-MPL cell lines that expressed WTJAK2, JAK2R564Q, JAK2V617F, or both JAK2R564Q and JAK2V617F mutations. Interestingly, our results showed that despite JAK2R564Q and the well-described JAK2V617F mutation residing within the same region, and causing similar levels of increased JAK2 activity, these 2 mutations have differing effects on cell cycle and proliferation. The JAK2 kinase activity, pMPL, and pJAK2 levels were all significantly increased compared with WTJAK2 controls and were comparable in all of the JAK2 mutants. Downstream signaling was also increased in the JAK2R564Q mutant cells, but not to the same extent as in the JAK2V617F-expressing cells. Concurrent with these findings, JAK2R564Q offered a significant growth advantage over WTJAK2-expressing cells, mediated via a mild proliferative effect, and a much more pronounced anti-apoptotic effect. The proliferative effect of JAK2V617F was even more robust, and cells expressing this mutation were factor-independent.

To establish whether the weaker effects of JAK2R564Q, compared with JAK2V617F, were a result of differences in the levels of JAK2Tyr570 phosphorylation, a negative regulator of JAK2 activity,27,28 we determined the phosphorylation status of this residue in the 4 cell lines. However, Tyr570, similar to Tyr1007/8, was more phosphorylated in JAK2V617F-expressing cells compared with JAK2R564Q, excluding this negative regulation as a possible explanation for the more subtle effects of JAK2R564Q on cell proliferation. However, we did find differences in the expression of cell cycle regulators between the mutant JAK2 cell lines. Although levels of p27/Kip1, the G1-to-S transition cell cycle regulator, were decreased in JAK2V617F-expressing cells, consistent with previous reports,19,29 p27/Kip1 was still present in starved Ba/F3-MPL-JAK2R564Q cells. The JAK2R564Q mutation was able to significantly inhibit apoptosis in the absence of cytokines, as shown by reduced Annexin V staining and decreased PARP cleavage, although it did not cause cytokine-independence, as seen in JAK2V617F-expressing mutants. Overall levels of PARP were increased in JAK2R564Q cells and, to a much greater extent, in JAK2V617F-expressing cells, which may be a result of increased cell division in the JAK2 mutants. Regulation of phosphorylated JAK2R564Q levels by SOCS3 was observed, as well as increased ubiquitination of JAK2 and the targeting of the kinase for proteasomal degradation, although this effect was absent in the JAK2V617F-expressing mutants, which is consistent with previous findings in BaF/3 cells.20 However, it should be noted that SOCS3 regulation of JAK2V617F appears context-dependent and/or dependent on a mutant JAK2 level, as SOCS3 has been shown to inhibit JAK2V617F signaling in HEK cells.21 In all assays, the double-mutant cell line, expressing both JAK2R564Q and JAK2V617F, was phenotypically very similar to the JAK2V617F cell line, indicating that the effects of the JAK2V617F mutation are dominant over those of JAK2R564Q. However, a mildly additive cell growth effect was seen in the double mutant cells, over the JAK2V617F-only expressers (Figure 4A), suggesting there may be potential cellular mechanisms used by JAK2R564Q and not JAK2V617F that we have not yet identified.

It is intriguing that despite the similar localization of the 2 MPN-causing mutations of JAK2, and the fact that they result in the same levels of increased kinase activity in biochemical assays, their effects in a cellular setting are very different; our results indicate this to be a result of differences in the regulation of the kinase. p27/Kip1 levels are reduced in JAK2V617F-expressing cells, but not in JAK2R564Q-expressing cells, indicating that with JAK2V617F expression, the cells can escape cell cycle regulation. In addition, JAK2R564Q is controlled by a negative feedback mechanism involving SOCS3, whereas the JAK2V617F mutant is not. It is conceivable that the patient with the JAK2R564Q mutation developed ET, rather than PV, because of the remaining presence of regulatory mechanisms that can somewhat control the hyperactivity caused by the JAK2 mutation. Recent reports have also shown allelic burden to have an important role in disease phenotype determination.30,31 We predict that the index patient in this study is heterozygous for JAK2R564Q, as his father does not carry the mutation. Our preliminary results also suggest that JAK2R564Q has a much stronger effect on cell viability when signaling through MPL than through EPOR. The panoply of signaling proteins that EPOR recruits is undoubtedly different to those recruited by MPL, and we speculate that the proteins involved in MPL signaling may be more likely to interact with JAK2R564Q. This preference to signal through MPL may also provide a possible explanation of why the patient developed ET, rather than PV, as MPL predominantly drives platelet production.

Our studies further show that JAK2V617F-expressing cells were sensitive to similar concentrations of the JAK inhibitor, ruxolitinib, to those recently described using SET-2/UKE-1 (JAK2V617F-positive leukemia) cells (100 nM),32 with an IC50 of 114.7 nM, which is comparable to a previously reported IC50 of 127 nM for JAK2V617F-positive BaF/3 cells.33 However, consistent with our findings demonstrating tighter control of JAK2 activity, JAK2R564Q-expressing cells were far more sensitive to ruxolitinib treatment, showing significant decreases in viable cell number at 1000-fold lower concentrations (0.1 nM), with an eightfold lower IC50 value. These results indicate that lower doses of ruxolitinib may be used to successfully treat patients with MPNs associated with JAK2 mutations other than JAK2V617F. Low doses are particularly desirable, as ruxolitinib inhibits both mutant and WT JAK2 nondiscriminately, functioning as an adenosine triphosphate-competitive inhibitor of JAK2. Therefore, patients given standard doses of the drug commonly experience adverse effects such as myelosuppression.34 Given that these alternative JAK2 mutations may be germline, as in this case, possibly requiring patients to begin treatment at an early age, and that JAK2 inhibitor therapy does not eradicate the MPN clone, treatment is necessary throughout life, making a low dose additionally advantageous.

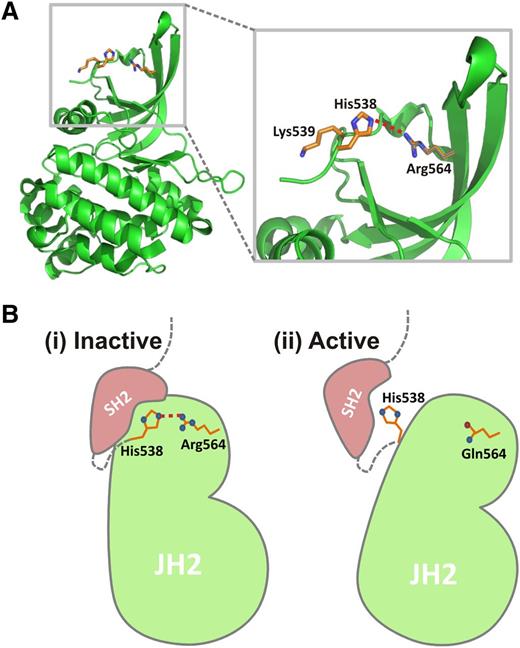

In addition to the JAK2V617F mutation in exon 14, insertion/deletion events in exon 12 have also been shown to contribute to MPNs.8,9 Further mutations involving exons 12 through 15, including Arg564, were identified in a large screening of blood samples from suspected MPN patients,7 although confirmation of their contribution to MPN is now required. As this region encodes the pseudokinase domain, these mutations, similar to JAK2V617F, may interrupt the regulation of JAK2 activity. As well as JAK2R564Q, the mutation JAK2R564L was also discovered in this study, highlighting the importance of Arg564 and suggesting that mutation of this residue has specific consequences. The recently published crystal structure of the JH2 domain16 revealed that the V617F mutation causes the stabilization of α-helix C in the N lobe of JH2, enabling transphosphorylation of the JH1 kinase domain, and therefore, hyperactivation of JAK2. However, the mechanism by which the JAK2R564Q mutation causes JAK2 hypersensitivity remains unclear. One possible explanation, based in the JH2 domain crystal structure,16 is that JAK2R564 may form a hydrogen bond with JAK2H538 (Figure 6A). Both JAK2H538L and JAK2K539I have been described as activating mutations in the SH2-pseudokinase domain linker,35 possibly as a result of H538 and K539 facilitating an inhibitory interaction with the SH2 domain. The R564–H538 hydrogen bond may position H538 for this inhibitory interaction and anchor the rest of the kinase domain relative to the SH2 domain (Figure 6Bi). This hydrogen bond would be broken in the JAK2R564Q mutant, preventing the inhibitory interaction between H538 and the SH2 domain, leading to JAK2 activation (Figure 6Bii). Further studies are now required to determine whether this is indeed the mechanism responsible.

Potential inhibitory role of Arg564. (A) JAK2 pseudokinase domain structure16 showing position of Arg564 and a potential interaction with His538. Given the close proximity of these 2 residues, a hydrogen bond (dashed red line) may form between them. (B) Model to show a potential mechanism for an inhibitory role of Arg564. (i) Both K539I and H538L have been described as activating mutations,35 possibly because of His538 and Lys539 being involved in inhibitory interactions with the SH2 domain (pink). The Arg564–His538 H-bond (dashed red line) may position His538 for this inhibitory interaction and anchor the rest of the kinase domain relative to the SH2 domain, keeping JAK2 in an inactive state. (ii) On mutation of Arg to Gln (R564Q), this interaction would be broken, so that His538 is no longer held in place for the inhibitory interaction with the SH2 domain. Further experiments are now required to determine whether Arg564 is indeed involved in this potential inhibitory mechanism.

Potential inhibitory role of Arg564. (A) JAK2 pseudokinase domain structure16 showing position of Arg564 and a potential interaction with His538. Given the close proximity of these 2 residues, a hydrogen bond (dashed red line) may form between them. (B) Model to show a potential mechanism for an inhibitory role of Arg564. (i) Both K539I and H538L have been described as activating mutations,35 possibly because of His538 and Lys539 being involved in inhibitory interactions with the SH2 domain (pink). The Arg564–His538 H-bond (dashed red line) may position His538 for this inhibitory interaction and anchor the rest of the kinase domain relative to the SH2 domain, keeping JAK2 in an inactive state. (ii) On mutation of Arg to Gln (R564Q), this interaction would be broken, so that His538 is no longer held in place for the inhibitory interaction with the SH2 domain. Further experiments are now required to determine whether Arg564 is indeed involved in this potential inhibitory mechanism.

The precise genetic foundations of familial MPNs have proven difficult to define (reviewed in Cross36 ). Recently, familial thrombocytosis has been associated with a germline MPL mutation37 and a TET2 truncation mutation,38 but evidence so far has shown that JAK2 mutations, particularly JAK2V617F, are acquired independently by individuals. Although 2 recent reports have associated a germline JAK2V617I mutation with familial thrombocytosis,22,23 our study is the first to demonstrate the contribution of a novel germline mutation involving an alternative JAK2 residue to MPN development and to outline the potential mechanisms responsible for causing familial thrombocytosis. We hypothesize that the JAK2R564Q mutation prevents apoptosis in hematopoietic stem cells and megakaryocyte progenitors, giving rise to a moderate increase in platelets. Importantly, even though this mutation is localized to the same JH2 pseudokinase domain, its effects on cell survival and proliferation are significantly different to the JAK2V617F mutation. Our work provides an insight into the functionality of alternative, clinically relevant JAK2 mutations and may aid in the development or modification of therapeutic strategies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Kenneth Kaushansky for helpful discussions and for reading and editing the manuscript. We also thank Dr Dai from Quest Diagnostics for the sequencing data. We thank Jean Wainer and Professor Wadie Bahou (Stony Brook University) for kindly providing the myeloid genomic DNA samples.

The authors were supported by the State University of New York Research Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: All authors have substantially contributed to the content of the paper and have agreed to the submission in its current format. S.L.E. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; M.E.C. and V.S. contributed to study design, study implementation, and writing of the manuscript; L.M.C. and M.E.R. performed research; M.A.S. was responsible for interpreting the location of the mutation within in the 3-dimensional structure, predicting possible interactions, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; E.L.C. completed the patient analysis and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; and I.S.H. designed and performed experiments, interpreted data, supervised the project, and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ian S. Hitchcock, Department of Medicine, Stony Brook University, 101 Nicholls Rd, HSC T15-89, Stony Brook, NY 11794; e-mail: ian.hitchcock@stonybrookmedicine.edu.