Abstract

Of all the outcomes of Plasmodium falciparum infection, the coma of cerebral malaria (CM) is particularly deadly. Malariologists have long wondered how some patients develop this organ-specific syndrome. Data from two recent publications support a novel mechanism of CM pathogenesis in which infected erythrocytes (IEs) express specific virulence proteins that mediate IE binding to the endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR). Malaria-associated depletion of EPCR, with subsequent impairment of the protein C system promotes a proinflammatory, procoagulant state in brain microvessels.

Introduction

Malaria is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the developing world. The virulence of Plasmodium falciparum is mediated by parasite proteins on the surface of infected erythrocytes (IEs), which anchor these cells to the microvascular endothelium of virtually every organ and tissue. Proteins of the P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) family mediate this adhesion through specific binding to multiple endothelial cell (EC) receptors, including CD36, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), E-selectin, and CD31 (PECAM-1), and to placental chondroitin sulfate A (CSA).1 Binding to endothelium results in widespread sequestration of IEs and hence their reduced clearance from the bloodstream by the spleen (Figure 1). Adherent IEs also activate ECs, leading to proinflammatory and procoagulant responses, reduced barrier function, and impaired vasomotor tone. Postmortem studies have provided evidence linking organ-specific sequestration of P. falciparum to some forms of clinical disease. Thus, while this parasite promotes local IE-EC interactions for its own survival, these interactions produce the clinical manifestations of malaria.

PfEMP1-endothelial receptor interactions mediate microvascular bed–specific sequestration of P. falciparum IEs. (A) The panel shows a typical microvessel found in a variety of organs and tissues in patients with malaria. In the latter half of their 48-hour life cycle, P. falciparum parasites sequester in microvessels and thus avoid clearance from the bloodstream by the spleen. The parasite shown on the left is clonally expressing a PfEMP1 variant on the IE surface that binds CD36 on ECs. In addition to CD36, ECs may also express EPCR, PECAM-1, and ICAM-1. IE binding to these receptors is encoded by specific PfEMP1 domain cassettes (DCs): DC8 and DC13 bind EPCR, DC5 binds PECAM-1, and DC4 binds ICAM-1. Parasites expressing a PfEMP1 variant containing more than one DC presumably bind more than one receptor on individual ECs. Activation of the endothelium by developing parasites and downstream events such as secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, deposition of fibrin, and loss of barrier integrity, result in microvascular inflammation, obstruction, and perivascular leakage. (B) IE sequestration in four different organs. Pregnancy-associated malaria is an organ-specific syndrome initiated by the expression of the PfEMP1 variant VAR2CSA (ie, DC2), which mediates IE binding to placental CSA expressed by syncytiotrophoblasts. In this case, the expression of a specific PfEMP1 variant causes the organ-specific syndrome. In a new model of pathogenesis, CM is initiated by the expression of a PfEMP1 variant containing DC8 or DC13 (green circles), which mediates IE binding to EPCR on brain endothelium. (This same PfEMP1 variant may also contain DC4 [purple circles], which may strengthen the binding of the IE to the same brain EC by binding ICAM-1.) In this case, malaria-induced shedding of the brain’s constitutively low levels of EPCR and PfEMP1-mediated inhibition of EPCR function cause the organ-specific syndrome of CM. In other organs (eg, lung) these same DC8- and DC13-expressing IEs may contribute to disease but other receptor–DC-binding pairs are proposed to cause organ-specific clinical syndromes (eg, respiratory distress). Like CM, respiratory distress and dyserythropoiesis-associated anemia are organ-specific malaria syndromes that may occur alone or in combination with CM. For these two syndromes, it is not yet known whether specific PfEMP1–endothelial receptor interactions, organ-specific differences in expression of endothelial anti- and procoagulants, or both, contribute to their pathology.

PfEMP1-endothelial receptor interactions mediate microvascular bed–specific sequestration of P. falciparum IEs. (A) The panel shows a typical microvessel found in a variety of organs and tissues in patients with malaria. In the latter half of their 48-hour life cycle, P. falciparum parasites sequester in microvessels and thus avoid clearance from the bloodstream by the spleen. The parasite shown on the left is clonally expressing a PfEMP1 variant on the IE surface that binds CD36 on ECs. In addition to CD36, ECs may also express EPCR, PECAM-1, and ICAM-1. IE binding to these receptors is encoded by specific PfEMP1 domain cassettes (DCs): DC8 and DC13 bind EPCR, DC5 binds PECAM-1, and DC4 binds ICAM-1. Parasites expressing a PfEMP1 variant containing more than one DC presumably bind more than one receptor on individual ECs. Activation of the endothelium by developing parasites and downstream events such as secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, deposition of fibrin, and loss of barrier integrity, result in microvascular inflammation, obstruction, and perivascular leakage. (B) IE sequestration in four different organs. Pregnancy-associated malaria is an organ-specific syndrome initiated by the expression of the PfEMP1 variant VAR2CSA (ie, DC2), which mediates IE binding to placental CSA expressed by syncytiotrophoblasts. In this case, the expression of a specific PfEMP1 variant causes the organ-specific syndrome. In a new model of pathogenesis, CM is initiated by the expression of a PfEMP1 variant containing DC8 or DC13 (green circles), which mediates IE binding to EPCR on brain endothelium. (This same PfEMP1 variant may also contain DC4 [purple circles], which may strengthen the binding of the IE to the same brain EC by binding ICAM-1.) In this case, malaria-induced shedding of the brain’s constitutively low levels of EPCR and PfEMP1-mediated inhibition of EPCR function cause the organ-specific syndrome of CM. In other organs (eg, lung) these same DC8- and DC13-expressing IEs may contribute to disease but other receptor–DC-binding pairs are proposed to cause organ-specific clinical syndromes (eg, respiratory distress). Like CM, respiratory distress and dyserythropoiesis-associated anemia are organ-specific malaria syndromes that may occur alone or in combination with CM. For these two syndromes, it is not yet known whether specific PfEMP1–endothelial receptor interactions, organ-specific differences in expression of endothelial anti- and procoagulants, or both, contribute to their pathology.

EC heterogeneity

ECs demonstrate remarkable heterogeneity in structure and function, space and time, and health and disease.2 Spatial and temporal differences in the structure and function of ECs ultimately reflect differences in messenger RNA and protein expression. In fact, few if any EC-restricted proteins are uniformly expressed across the vascular tree (possible exceptions include VE-cadherin and CD31). ECs from different vascular beds express overlapping but distinct transcriptional profiles and cell surface receptors. These differences have led to the concept of vascular “ZIP codes,” or the notion that each vascular bed possesses a unique molecular signature (or address).3 An important goal in medicine is to use these vascular addresses to develop diagnostic, imaging, and therapeutic strategies. In cerebral malaria (CM), P. falciparum parasites have evolved to take advantage of specific ZIP codes in promoting their survival in different organs.

Malaria and vascular diversity

P. falciparum harbors approximately 60 var genes, each of which encodes a different variant of PfEMP1. Each individual parasite expresses a single var gene at a time, maintaining all other var genes in a transcriptionally silent state. Almost all members of the var family are classified into one of 3 major groups (A, B, and C) based on a combination of chromosomal location, transcription direction, and upstream promoter sequence. Clonal antigenic variation of var modifies the antigenic and binding properties of the IE. In keeping with the theme of EC heterogeneity, each of the host receptors for PfEMP1 has a unique expression pattern in the vasculature. For example, CD36 is expressed in microvascular ECs but is not detectable in ECs from certain large vessels, including muscular arteries and hepatic veins.4 ICAM-1 and E-selectin are differentially expressed in the endothelium under basal conditions and in response to inflammation.2 The ability of PfEMP1 variants to target different endothelial receptors, which themselves are distributed heterogeneously, helps to explain why some patients with malaria present with organ-specific syndromes. For example, in pregnancy-associated malaria, the VAR2CSA variant of PfEMP1 binds placental CSA located in the villous stromal cores of the placenta, which become exposed to maternal blood upon denudation of syncytiotrophoblasts.5,6 For years, investigators have speculated that other PfEMP1 variants will prove to bind receptors that are preferentially expressed in one or another vascular bed, such as those of the brain, lung, kidney, or bone marrow (Figure 1). In the next section, we discuss one such receptor, namely the endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR), whose relatively low expression levels and nonredundant functionality in the brain provide clues toward understanding the focal manifestations of CM.

Severe malaria and EPCR binding

A recent study by Turner et al7 showed that PfEMP1 variants associated with severe malaria, namely DC8 (group B/A hybrid) and DC13 (group A), bind to EPCR. Binding was observed not only to brain ECs but also to ECs derived from other vascular beds. In contrast, group B and C variants of PfEMP1 (which are associated with less severe disease) were found to bind to CD36. Although these studies were carried out under static conditions and in the absence of proinflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), they provide compelling evidence for PfEMP1 variant-specific binding and are consistent with the hypothesis that PfEMP1 proteins have diverged into EPCR- and CD36-binding types.

The identification of EPCR as a receptor for specific PfEMP1 variants was unexpected because EPCR is most widely known as the receptor for (activated) protein C, which binds via a unique N-terminal γ-carboxyglutamic acid domain that is absent in PfEMP1.8 Interestingly, EPCR has also been shown to bind to Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18), and this interaction contributes to monocyte adhesion to ECs.9 Thus, EPCR and ICAM-1 both share the ability to bind to Mac-1 and PfEMP1, and architectural similarities between the interactive surface of CD11b and PfEMP1 may be anticipated. Another recently identified EPCR binding partner is a specific variant of the T-cell receptor present on a subpopulation of γδ T cells.10 Although EPCR is homologous to CD1/major histocompatibility complex molecules, binding of the T-cell receptor to EPCR did not result in T-cell activation unless a secondary stress signal was provided. Interestingly, upregulation of ICAM-1 was identified as a costimulatory ligand that potentiates EPCR-dependent activation of γδ T cells.10 Previous studies suggest that γδ T cells are involved in the initial stage of P. falciparum infection,11 but currently available evidence is insufficient to support a pathogenic role of EPCR-targeting γδ T cells in CM. In any event, the various lines of evidence supporting a functional link between EPCR and ICAM-1 in leukocyte–EC interactions raise the distinct possibility that that these two molecules cooperate in the sequestration of IEs in cerebral microvessels.

Explaining organ specificity in CM

Malariologists have long asked why some patients with malaria present with vascular bed-specific sequestration of IEs in the brain. Many hypotheses have been proposed, including the local expression and/or upregulation of cell surface receptors on blood-brain barrier ECs that bind to IEs, platelet-mediated agglutination of IEs, and platelet-mediated activation of ECs.12 Pathologic studies of brain tissue from children who died of CM have demonstrated not only sequestration of IEs in cerebral blood vessels but also local deposition of microthrombi and fibrin in the absence of disseminated coagulopathy,13,14 as well as platelet accumulation.15 Of the few autopsy studies that have been reported of fatal CM in adults (virtually all from Thailand, Vietnam, or India), none has systematically examined for the presence of fibrin. However, they do universally report the common finding of petechial hemorrhages, which is an indication of coagulopathy.

The vast majority of hypercoagulable states that involve a systemic imbalance of hemostatic factors (eg, antithrombin III deficiency or factor V Leiden [FVL]) are associated with local thrombosis in characteristic sites of the vasculature.16 By analogy, in CM, the systemic distribution of IEs results in organ-specific fibrin deposition in the brain. We have previously argued that the systemic imbalance–local thrombosis paradox is best explained by vascular bed–specific differences in the expression of endothelial anticoagulants and procoagulants.16 In keeping with this hypothesis, a recent study by Moxon et al13 implicates a role for EPCR in localizing the thrombotic manifestations of CM in the brain.

Functionally, EPCR is well known for its involvement in the activation of protein C.17 EPCR is highly expressed in arteries and veins but is present at low levels in many microvascular beds, including the brain.18 Physiologic activation of protein C on the EC surface requires both thrombomodulin (TM) and EPCR. APC mediates important anticoagulant activities via the proteolytic inactivation of cofactors factor Va and VIIIa and reduced APC activity, as occurs in patients with congenital deficiency of protein C or APC resistance (eg, FVL), conveys an increased risk for venous thrombosis.8

Moxon et al13 have shown that the normally low levels of EPCR in brain microvessels are further downregulated in CM, with a negative association between IE sequestration and EPCR staining. In contrast, they were unable to detect TM expression in CM or non-CM control brains. However, TM expression in subcutaneous microvessels, where IE sequestration also occurs, was markedly reduced. The changes in EPCR and TM were associated with increased levels of sEPCR) and soluble TM in the cerebrospinal fluid. While these latter findings suggest that the receptors are shed from the surface of brain ECs, they do not rule out a role for transcriptional and/or posttranslational mechanisms of receptor loss. Interestingly, Turner et al7 reported that EPCR-mediated parasite cytoadhesion may interfere with protein C binding and activation, providing yet another mechanism of attenuated EPCR function.

These two studies suggest a model in which CM triggers shedding of already low levels of TM and EPCR in the brain and inhibits the function of residual EPCR, resulting in reduced protein C activation, unchecked thrombin generation, and increased local fibrin deposition (Figure 2). Previous studies have shown that ECs from CM-susceptible mice or patients with CM are inherently more reactive to TNF-α.19 By extension, perhaps ECs of some individuals have inherent differences in the expression and/or activity of EPCR or TM, which render them more or less vulnerable to developing CM. For example, PROCR haplotype A3, which is associated with increased levels of sEPCR,20 may protect against severe malaria by inhibiting the binding of DC8-/DC13-expressing parasites to ECs.7 Furthermore, TNF-α–mediated phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) secretion from leukocytes and possibly brain ECs may contribute to EPCR encryption and loss of its APC-binding function that results from sPLA2-mediated modification to phospholipid embedded in EPCR while potentially leaving interactions with IEs relatively unaffected.21

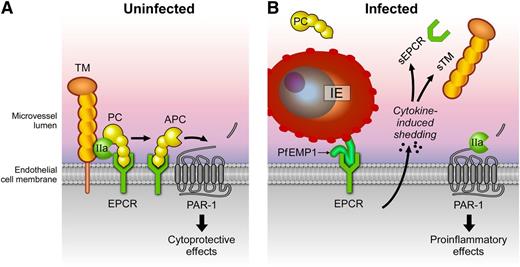

Effects of P. falciparum infection on the protein C system. (A) A normal functional protein C system is depicted in which protein C is activated by thrombin (IIa) bound to TM on the EC membrane. Generation of activated protein C (APC) is enhanced by recruitment of protein C to the cell membrane by binding to EPCR. After activation, APC conveys anticoagulant and cytoprotective responses. APC’s anticoagulant activities involve dissociation from EPCR and binding of APC to negatively charged phospholipid membranes such as those on activated platelets where APC proteolytically inactivates factors Va and VIIIa (not shown). Binding of APC to EPCR facilitates APC-mediated activation of protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR-1) and induction of protective PAR-1 signaling, which contributes to maintaining a quiescent state of the endothelium. (B) During P. falciparum infection, IEs (expressing PfEMP1 variants containing DC8 and/or DC13) bind to EPCR and promote EC activation. Activated ECs release proinflammatory cytokines, which, in turn, induce shedding of TM and EPCR from the cell surface and release of the ectodomains soluble TM and soluble EPCR (sEPCR) in the circulation. In addition, PfEMP1 binding to EPCR inhibits the function of the receptor. Collectively, these changes severely impair the ability of the endothelium to generate APC, setting up a vicious cycle of procoagulant and proinflammatory reactions leading to further endothelial dysfunction augmented by proinflammatory PAR-1 signaling by thrombin.

Effects of P. falciparum infection on the protein C system. (A) A normal functional protein C system is depicted in which protein C is activated by thrombin (IIa) bound to TM on the EC membrane. Generation of activated protein C (APC) is enhanced by recruitment of protein C to the cell membrane by binding to EPCR. After activation, APC conveys anticoagulant and cytoprotective responses. APC’s anticoagulant activities involve dissociation from EPCR and binding of APC to negatively charged phospholipid membranes such as those on activated platelets where APC proteolytically inactivates factors Va and VIIIa (not shown). Binding of APC to EPCR facilitates APC-mediated activation of protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR-1) and induction of protective PAR-1 signaling, which contributes to maintaining a quiescent state of the endothelium. (B) During P. falciparum infection, IEs (expressing PfEMP1 variants containing DC8 and/or DC13) bind to EPCR and promote EC activation. Activated ECs release proinflammatory cytokines, which, in turn, induce shedding of TM and EPCR from the cell surface and release of the ectodomains soluble TM and soluble EPCR (sEPCR) in the circulation. In addition, PfEMP1 binding to EPCR inhibits the function of the receptor. Collectively, these changes severely impair the ability of the endothelium to generate APC, setting up a vicious cycle of procoagulant and proinflammatory reactions leading to further endothelial dysfunction augmented by proinflammatory PAR-1 signaling by thrombin.

The findings by Moxon et al are supported by previous studies in which protein C-null mice or mice carrying FVL demonstrate selective fibrin deposition in brain blood vessels.22,23 These results contrast with those of antithrombin III-null mice, which form fibrin deposits in the heart and liver but not the brain.24 Interestingly, mice deficient in endothelial TM have fibrin deposition in many organs but not the brain.25 These latter findings notwithstanding, the collective findings support a model of vascular bed-specific hemostasis in which the brain relies on a tenuous balance between procoagulant forces and APC-mediated inactivation of factor V to maintain blood fluidity. As outlined in the next section, the role of EPCR/APC in CM is likely to extend well beyond its effects on coagulation and include alterations in cytoprotection.

EPCR in CM: beyond cytoadhesion and coagulation

In addition to its cofactor role in protein C activation, EPCR plays a central role in the protein C cytoprotective pathway by facilitating APC-mediated activation of PAR-1 (Figure 2). EPCR- and PAR-1–dependent direct cytoprotective effects of APC on cells include beneficial alterations in gene expression profiles, activation of anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic responses, and protection of endothelial barrier function.17 Remarkably, imbalances of each of these APC cytoprotective activities have been implicated in CM pathogenesis, such as would be expected from loss of EPCR and consequent loss of the cytoprotective effects of APCs. For example, APC downregulates messenger RNA expression of at least 5 of the 13 previously described PfEMP1 targets, including ICAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, E-selectin, and thrombospondin-1.7,8 APC also inhibits endothelial activation by inhibiting the expression of TNF-α and cell adhesion molecules and by enhancing barrier function through the protective effects of sphingosine-1-phosphate, endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and angiopoietin-1/Tie2 signaling (all proposed targets in CM therapy).17,26 Finally, EPCR-dependent transport of APC across the intact blood-brain barrier allows APC to exert critical neuroprotective and antiapoptotic effects on both sides of the blood-brain barrier.17 The overall importance of EPCR in mediating the cytoprotective effects of APC in the brain was evidenced by a study in which mice expressing low EPCR levels (<10%) demonstrated organ-specific barrier dysfunction in the brain.27 The extent to which impaired EPCR-mediated activation of protein C and/or APC-mediated cytoprotective effects contributes to CM, however, requires additional study.

Summary and future directions

The two recent studies by Turner et al7 and Moxon et al13 have provided important new insights into the role of EPCR in malaria. It would appear that EPCR functions as a two-edged sword. On one hand, it binds IEs, setting the stage for their sequestration and the development of clinical disease. On the other hand, EPCR is required to maintain blood fluidity and endothelial cytoprotection. In the brain, the normally low levels of EPCR may provide relative protection against IE sequestration. At the same time, however, low-level expression of EPCR and TM (both required to activate protein C) render the brain particularly vulnerable to further depletion of these APC-generating receptors. PfEMP1-mediated inhibition of EPCR function and malaria-associated reduction in EPCR and TM expression on the surface of ECs may be just enough to tip the balance toward organ-specific pathology in the brain.

These two studies raise many interesting questions and point to new avenues of basic and translational research. For example, will targeting the PfEMP1–EPCR interaction be a viable approach to curb the sequestration of IEs, improve clearance of IEs in the spleen, and reverse the vicious cycle of vascular deterioration in CM? Can patients with CM benefit from treatment with recombinant APC? If loss of EPCR-mediated cytoprotection plays a critical role in CM, could patients be administered cytoprotective-selective APC variants, which are associated with a lower bleeding risk? Or would such variants be rendered ineffective by the low-level expression of EPCR in CM? Will novel insights into the metabolism of EPCR on the cell surface provide new experimental strategies to mitigate EPCR depletion in CM? Finally, to what extent can the findings of Moxon et al in children be extrapolated to adults with CM?

The new data may also have important implications for the study of malaria pathogenesis and protection in general. Identifying specific interactions between particular PfEMP1 domains and EPCR sets a precedent for the discovery of others, such as the recent identification of PfEMP1 DC4 as the ligand for ICAM-1 and DC5 as the ligand for CD31 (PECAM-1).28,29 Are additional PfEMP1 host–receptor interactions involved in the pathogenesis of other organ-specific malaria syndromes (all of which can occur in isolation) such as respiratory distress, renal failure, and severe anemia? The sickle-cell trait, which provides remarkable protection against CM, has been shown to affect the amount and distribution of PfEMP1 on the surface of IEs, resulting in weakened cytoadherence interactions.30 Is it possible that heterozygosity for hemoglobin S confers its protection by occupying fewer EPCR sites and/or by altering the extent of EPCR shedding? These and other hypotheses can be readily tested in experimental systems that measure the effect of hemoglobin type on in vitro correlates of CM pathogenesis. Exploiting the known CM-protective effects of hemoglobin A/S erythrocytes may help identify the most clinically relevant targets for therapeutic intervention.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Steve Moskowitz for his artwork.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL076540 [W.C.A.] and HL104165 [L.O.M.]); and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R.M.F.).

Authorship

Contribution: W.C.A., L.O.M., and R.M.F. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: William C. Aird, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Molecular and Vascular Medicine, RN-227, 330 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail: waird@bidmc.harvard.edu.

![Figure 1. PfEMP1-endothelial receptor interactions mediate microvascular bed–specific sequestration of P. falciparum IEs. (A) The panel shows a typical microvessel found in a variety of organs and tissues in patients with malaria. In the latter half of their 48-hour life cycle, P. falciparum parasites sequester in microvessels and thus avoid clearance from the bloodstream by the spleen. The parasite shown on the left is clonally expressing a PfEMP1 variant on the IE surface that binds CD36 on ECs. In addition to CD36, ECs may also express EPCR, PECAM-1, and ICAM-1. IE binding to these receptors is encoded by specific PfEMP1 domain cassettes (DCs): DC8 and DC13 bind EPCR, DC5 binds PECAM-1, and DC4 binds ICAM-1. Parasites expressing a PfEMP1 variant containing more than one DC presumably bind more than one receptor on individual ECs. Activation of the endothelium by developing parasites and downstream events such as secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, deposition of fibrin, and loss of barrier integrity, result in microvascular inflammation, obstruction, and perivascular leakage. (B) IE sequestration in four different organs. Pregnancy-associated malaria is an organ-specific syndrome initiated by the expression of the PfEMP1 variant VAR2CSA (ie, DC2), which mediates IE binding to placental CSA expressed by syncytiotrophoblasts. In this case, the expression of a specific PfEMP1 variant causes the organ-specific syndrome. In a new model of pathogenesis, CM is initiated by the expression of a PfEMP1 variant containing DC8 or DC13 (green circles), which mediates IE binding to EPCR on brain endothelium. (This same PfEMP1 variant may also contain DC4 [purple circles], which may strengthen the binding of the IE to the same brain EC by binding ICAM-1.) In this case, malaria-induced shedding of the brain’s constitutively low levels of EPCR and PfEMP1-mediated inhibition of EPCR function cause the organ-specific syndrome of CM. In other organs (eg, lung) these same DC8- and DC13-expressing IEs may contribute to disease but other receptor–DC-binding pairs are proposed to cause organ-specific clinical syndromes (eg, respiratory distress). Like CM, respiratory distress and dyserythropoiesis-associated anemia are organ-specific malaria syndromes that may occur alone or in combination with CM. For these two syndromes, it is not yet known whether specific PfEMP1–endothelial receptor interactions, organ-specific differences in expression of endothelial anti- and procoagulants, or both, contribute to their pathology.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/123/2/10.1182_blood-2013-09-521005/4/m_163f1.jpeg?Expires=1767709114&Signature=OS4gGGsdQY909LMSeV8SlGGyzy7xhKP~9pCdAzbrP1PtGcTnIaUyERBZX-rgeNYTpbnLQVL9o1ob-W~adbYeT29hSthPnU3EyK6ENJEok6faH7RL-N79X0iDWGnZYPs0h9qITWr1whXwWkbBA0MGjQrdQaYynAX8DfPzqAwT0DxO8iAh7EheKC~lOK~rBn9quQS4NeoD--ynOuzu7FrD40j8g~ZzxHHFmEijWPtih1ugAmY~ziCqOCtm9-xlgMarsle8ariqmFxMYr7TYXYq9iCl2acnRYaLizh01LtRyQDViXNaeIzGgLn1eS6r2T-SOsUctXmpjEQS7iDrjZZexA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal