Key Points

Hundreds of lineage-specific lncRNAs are expressed during mouse and human erythropoiesis.

Most mouse erythroid lncRNAs are not expressed in human erythroblasts and vice versa, yet some appear to be functional.

Abstract

Mammals express thousands of long noncoding (lnc) RNAs, a few of which are known to function in tissue development. However, the entire repertoire of lncRNAs in most tissues and species is not defined. Indeed, most lncRNAs are not conserved, raising questions about function. We used RNA sequencing to identify 1109 polyadenylated lncRNAs expressed in erythroblasts, megakaryocytes, and megakaryocyte-erythroid precursors of mice, and 594 in erythroblasts of humans. More than half of these lncRNAs were unannotated, emphasizing the opportunity for new discovery through studies of specialized cell types. Analysis of the mouse erythro-megakaryocytic polyadenylated lncRNA transcriptome indicates that ∼75% arise from promoters and 25% from enhancers, many of which are regulated by key transcription factors including GATA1 and TAL1. Erythroid lncRNA expression is largely conserved among 8 different mouse strains, yet only 15% of mouse lncRNAs are expressed in humans and vice versa, reflecting dramatic species-specificity. RNA interference assays of 21 abundant erythroid-specific murine lncRNAs in primary mouse erythroid precursors identified 7 whose knockdown inhibited terminal erythroid maturation. At least 6 of these 7 functional lncRNAs have no detectable expression in human erythroblasts, suggesting that lack of conservation between mammalian species does not predict lack of function.

Introduction

Long noncoding (lnc) RNAs, defined as a subclass of noncoding RNAs that exceeds 200 nucleotides, are highly diverse, with thousands identified in many cell types and species.1,2 LncRNAs play a variety of roles in eukaryotic development by regulating gene expression transcriptionally and posttranscriptionally. However, the vast majority of lncRNAs remain uncharacterized, and there is debate over what proportion of expressed lncRNAs actually has biological function.3 This issue is fueled by observations that orthologous lncRNAs expressed across species typically exhibit low nucleotide sequence conservation and that some lncRNAs transcribed in 1 species are not transcribed in others.

LncRNAs in hematopoiesis are just beginning to be defined.4,5 The human lncRNAs EGO and HOTAIRM1 regulate eosinophil granule protein expression and myeloid differentiation genes, respectively.6,7 LincRNA-EPS promotes the survival of mouse erythroblasts by suppressing Pycard, a pro-apoptotic gene.8 Imprinting of the lncRNA H19 regulates mouse hematopoietic stem cell quiescence, at least in part via its processing into the microRNA miR-675.9 Loss of Xist, an lncRNA that coordinates X chromosome inactivation in females, causes hematologic cancers in mice.10 A recent study defined lncRNAs expressed during murine erythropoiesis and used RNA interference (RNAi) to identify 12 with potential functions.11 However, comprehensive identification and analyses of lncRNAs expressed during all stages of hematopoiesis and in multiple species are lacking.

The current study uses deep sequencing of polyA+ RNA to examine lncRNA expression in purified murine megakaryocyte-erythroid precursors (MEPs), megakaryocytes, and erythroblasts as well as in human erythroblasts. We defined hundreds of lncRNAs unique to each cell type and focused on the erythroid lineage to investigate several questions related to lncRNA biology. First, do erythroid precursors express novel and/or lineage-specific lncRNAs? Second, how are erythroid lncRNAs regulated and to what extent is their transcription conserved between species? Finally, does conserved lncRNA expression (or lack thereof) predict whether they are biologically active? Our findings identify distinct populations of lncRNAs in mouse and human erythroblasts, very few of which have cross-species orthologs, and suggest developmental roles for multiple lncRNAs in terminal mouse erythropoiesis despite this lack of conservation.

Materials and methods

Cell purification

Animal studies were performed under approved ethical protocols at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and The National Institutes of Health. Murine hematopoietic populations were derived from embryonic day 14.5 day CD-1 fetal livers and bone marrow of C57BL/6 adult animals as described in supplemental Methods on the Blood Web site and Pimkin et al, 2013.12 G1E-ER4 cells were cultured as described previously,13 and RNA was extracted at 0, 3, 7, 14, 24, and 30 hours. Cultured human cord blood erythroblasts at distinct maturational stages were isolated by flow cytometry, as described.14 Total RNA was extracted using Qiagen RNeasy Kits.

RNA-sequencing analysis

Construction of complementary DNA libraries, sequencing, and bioinformatic analyses including lncRNA pipelines are provided in supplemental Methods.

ChIP-seq

The chromatin immunoprecipitation and massively parallel DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq) assay was performed as described.12

Mouse strain RNA-seq comparison

BAM files for mouse splenic erythroblast RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) from 8 different strains were obtained from the authors of Hosseini et al15 and the Cuffdiff tool was run to compute gene expression.

Mouse-human transcriptome comparisons

University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) pslMap tools16 were used to map mouse annotations to the human genome and transcriptome (and vice versa), as described in supplemental Methods.

RNAi studies

Embryonic day 14.5 fetal livers from CD-1 embryos were dissociated and immunodepleted of cells expressing mature lineage markers, as described.17 The progenitor cells were infected with retroviruses encoding short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) against lncRNAs and cultured as described in supplemental Methods.

To assess erythroid maturation, retrovirally infected cells were stained with H33342, Near-IR LiveDead stain, Ter119-PerCP-Cy5.5, and CD44-AF647 and analyzed on a Fortessa LSR flow cytometer. To optimize signal-to-noise ratios, cells infected with shRNA retrovirus were gated on a mid-high range of green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression that produced no phenotypes with the negative controls (vector only and shLuciferase) and maximal phenotype with positive controls (shGATA1, shFOG1) (supplemental Figure 4A). The shRNA sequences for the 7 functional lncRNAs are listed in supplemental Table 5. Antibodies and cell staining reagents are detailed in supplemental Methods.

Data access

Results

Novel cell-specific lncRNAs are expressed during mouse erythro-megakaryopoiesis

We used RNA-seq to identify and compare lncRNAs in primary murine E14.5 fetal liver erythroblasts, megakaryocytes cultured from murine fetal liver progenitors, and MEPs from mouse bone marrow. Strand-specific, paired-end, deep sequencing was performed on polyA+ RNA from biological replicates of each sample (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1A). We assembled the transcriptomes using the TopHat and Cufflinks packages18 and generated a high-confidence transcriptome of 13 131 genes expressed in at least 1 the 3 cell types. Appropriate expression patterns of lineage specific protein coding genes confirmed the purity of input cells (supplemental Figure 1B).

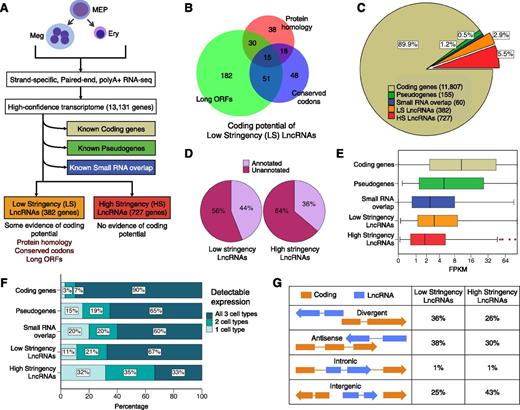

Identification and characterization of mouse erythro-megakaryocytic lncRNAs. (A) Bioinformatic pipeline for identification of lncRNAs. See “Materials and methods” for details. (B) Venn diagram showing protein coding potential of low-stringency lncRNAs as assessed by 3 different bioinformatic tools. Note that bioinformatic tools, even after calibration with test datasets (supplemental Figure 1C), show limited correlation with each other in determining coding potential. (C) Pie chart showing composition of the mouse erythro-megakaryocytic polyA+ transcriptome; 8.4% of genes are candidate lncRNA genes (low + high stringency). (D) Most erythromegakaryocytic lncRNAs are not annotated in RefSeq, UCSC, or Ensembl datasets. (E) Expression measured as FPKM for gene categories. LncRNA genes have overall lower expression than coding genes. (F) Cell specificity of RNAs according to type. Note that approximately one-third of high-stringency lncRNAs are detectable in only 1 of the cell types indicated at the top of panel A, as compared with 90% of coding genes, most of which are detectable in all 3 types. (G) Percentage of lncRNA genes in orientations relative to nearby coding genes. ORF, open reading frame.

Identification and characterization of mouse erythro-megakaryocytic lncRNAs. (A) Bioinformatic pipeline for identification of lncRNAs. See “Materials and methods” for details. (B) Venn diagram showing protein coding potential of low-stringency lncRNAs as assessed by 3 different bioinformatic tools. Note that bioinformatic tools, even after calibration with test datasets (supplemental Figure 1C), show limited correlation with each other in determining coding potential. (C) Pie chart showing composition of the mouse erythro-megakaryocytic polyA+ transcriptome; 8.4% of genes are candidate lncRNA genes (low + high stringency). (D) Most erythromegakaryocytic lncRNAs are not annotated in RefSeq, UCSC, or Ensembl datasets. (E) Expression measured as FPKM for gene categories. LncRNA genes have overall lower expression than coding genes. (F) Cell specificity of RNAs according to type. Note that approximately one-third of high-stringency lncRNAs are detectable in only 1 of the cell types indicated at the top of panel A, as compared with 90% of coding genes, most of which are detectable in all 3 types. (G) Percentage of lncRNA genes in orientations relative to nearby coding genes. ORF, open reading frame.

We identified coding genes, pseudogenes, and potential small RNA precursors based on genomic overlap with existing annotations. We investigated the coding potential of the remaining genes using 3 independent algorithms: (1) protein database homology with BlastX19 and Pfam20 ; (2) codon conservation with PhyloCSF21 ; and (3) presence of long open reading frames >100 amino acids with EMBOSS GetORF22 (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1C and supplemental Methods). Genes that had no evidence of coding potential based on all 3 criteria were classified as “high-stringency lncRNA” candidate genes and those that failed any 1 or more of them were classified as “low-stringency lncRNA” candidate genes. The coding potential tools had limited correlation with each other (Figure 1B), with numerous false positives and negatives occurring. For example, our pipeline assigned several known lncRNAs, including Xist, Tug1, Malat1, and LincRNA-EPS into the low-stringency group. This group likely represents a mixture of coding and lncRNA genes, reflecting the limitations of current bioinformatic tools in distinguishing between coding and noncoding genes. In total, we identified 1109 potential lncRNA genes (high + low stringency) transcribed during murine erythro-megakaryopoiesis (683 transcribed in erythroblasts), which constitute about 8.4% of genes producing polyA+ RNA transcripts in these cell types (Figure 1C). More than half of the identified lncRNAs were not annotated in public databases, including noncoding transcripts listed in RefSeq, UCSC, and Ensembl annotations16 (Figure 1D). Coding messenger RNAs (mRNAs) were expressed at higher levels than lncRNAs, as reflected by median fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads (FPKM) values (Figure 1E). As with coding mRNAs, lncRNAs showed clustered expression based on cell of origin (supplemental Figure 1D). However, ∼30% of high-stringency lncRNAs were detectable in just 1 of the 3 cell types examined, contrasting with coding mRNAs, of which ∼90% were detected in all 3 lineages (Figure 1F). This suggests that lncRNAs are more lineage-restricted than coding mRNAs and that RNA-seq analysis of previously uncharacterized cell types will identify unappreciated lncRNAs. The hematopoietic lncRNAs defined in this study segregated roughly equally into divergent transcripts with transcription start sites (TSS) within 300 bp of a coding gene TSS, antisense transcripts to coding genes, and intergenic transcripts (Figure 1G).

Because the erythroid RNA-seq was performed in mouse fetal liver erythroblasts, we compared lncRNA expression between fetal and adult erythropoiesis. Using a custom microarray with probes against the standard coding transcriptome and erythroid lncRNAs identified in this study, we profiled gene expression in adult mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors purified by fluorescent-activated cell sorting (supplemental Figure 2A). More than 85% of fetal liver erythroid lncRNAs were detected in adult erythroblasts. This rose to more than 90% when transcripts at the lowest quartile of expression (FKPM < 1) were excluded (supplemental Figure 2B). Thus, most mouse erythroid lncRNAs are expressed in both fetal liver and adult bone marrow erythroblasts. Moreover, these lncRNAs are coexpressed with protein-coding mRNAs that have defined roles in erythropoiesis (supplemental Figure 2B; supplemental Table 1). Alvarez-Dominguez et al show that lncRNAs are expressed at different levels in mouse fetal and adult erythroblasts11 ; however, our studies are consistent with theirs in that most lncRNAs are expressed at detectable levels in both cell types.

Most mouse erythro-megakaryocytic lncRNAs are transcribed from conventional gene promoters regulated by key hematopoietic transcription factors

It is unclear whether most lncRNAs are transcribed from genes with conventional promoters or whether they are transcribed from enhancers.23 We investigated this by performing genome-wide ChIP-seq for H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K36me3 histone marks on fetal liver erythroblasts and megakaryocytes (see Pimkin et al12 and Mouse ENCODE Consortium, manuscript in revision) and mapped these chromatin signatures to the genomic loci of coding and lncRNA genes. We classified gene TSSs with H3K4me3-high/H3K4me1-low signatures as promoters and those with H3K4me1-high/H3K4me3-low signatures as enhancers (Figure 2A).24 About 25% of the high-stringency lncRNA TSSs exhibited enhancer-like signatures, which was significantly greater (P = 10−12 for erythroblasts, 10−14 for megakaryocytes by Fisher’s exact test) than coding genes (<10%) (Figure 2B). Nonetheless, ∼75% of erythro-megakaryocytic lncRNAs were transcribed from regions with promoter-like signatures. Low-stringency lncRNAs arose from enhancers less frequently than high-stringency lncRNAs, but more frequently than coding genes, consistent with our interpretation that this group contains a mixture of protein coding and lncRNA genes.

Most mouse polyA+ erythro-megakaryocytic lncRNAs arise from conventional promoters and are regulated by key transcription factors. (A) Histone modifications H3K36me3, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 were determined globally by ChIP-seq and analyzed at gene TSSs. Composite profiles are shown for promoter signatures (H3K4me3-high/H3K4me1-low) and enhancer signatures (H3K4me3-low/H3K4me1-high). The x-axis shows distance from TSS; y-axis shows average peak score for the indicated modifications. (B) Relative proportions of enhancer and promoter signatures at the TSSs of erythro-megakaryocytic coding and lncRNA genes. (C) Transcription factor (TF) occupancy at erythro-megakaryocytic coding and lncRNA genes measured by ChIP-seq. The genes are subclassified according to whether they are up- or downregulated in erythroblasts or megakaryocytes compared with MEPs, as measured by RNA-seq. (D) The expression of erythroid coding and noncoding genes in the Gata1– mouse erythroblast line G1E-ER4 after activation of an estradiol-induced form of GATA1. (E) Model for megakaryocytic developmental priming. Genes with binding of a heptad of TFs in stem/progenitor cells are “primed” for megakaryocytic differentiation, and are activated during megakaryopoiesis and repressed during erythropoiesis. (F) Percentage of genes in each expression group showing occupancy by the TF heptad in the HPC-7 cell line. For both coding genes and lncRNAs, genes that are upregulated during megakaryopoiesis and either downregulated or unchanged during erythropoiesis show higher levels of genomic locus heptad occupancy in progenitor cells. Dn, downregulated; N, no change; Up, upregulated.

Most mouse polyA+ erythro-megakaryocytic lncRNAs arise from conventional promoters and are regulated by key transcription factors. (A) Histone modifications H3K36me3, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 were determined globally by ChIP-seq and analyzed at gene TSSs. Composite profiles are shown for promoter signatures (H3K4me3-high/H3K4me1-low) and enhancer signatures (H3K4me3-low/H3K4me1-high). The x-axis shows distance from TSS; y-axis shows average peak score for the indicated modifications. (B) Relative proportions of enhancer and promoter signatures at the TSSs of erythro-megakaryocytic coding and lncRNA genes. (C) Transcription factor (TF) occupancy at erythro-megakaryocytic coding and lncRNA genes measured by ChIP-seq. The genes are subclassified according to whether they are up- or downregulated in erythroblasts or megakaryocytes compared with MEPs, as measured by RNA-seq. (D) The expression of erythroid coding and noncoding genes in the Gata1– mouse erythroblast line G1E-ER4 after activation of an estradiol-induced form of GATA1. (E) Model for megakaryocytic developmental priming. Genes with binding of a heptad of TFs in stem/progenitor cells are “primed” for megakaryocytic differentiation, and are activated during megakaryopoiesis and repressed during erythropoiesis. (F) Percentage of genes in each expression group showing occupancy by the TF heptad in the HPC-7 cell line. For both coding genes and lncRNAs, genes that are upregulated during megakaryopoiesis and either downregulated or unchanged during erythropoiesis show higher levels of genomic locus heptad occupancy in progenitor cells. Dn, downregulated; N, no change; Up, upregulated.

LncRNA genes are likely regulated by cell-type–specific TFs, similar to coding genes,25 although this has yet to be demonstrated on a transcriptome-wide level in primary differentiated cells. We performed genome-wide ChIP-seq for GATA1 and TAL1 in erythroblasts and for GATA1, GATA2, TAL1, and FLI1 in megakaryocytes (see Pimkin et al,12 Wu et al,26 and Mouse ENCODE Consortium, in revision). We compared the binding of these TFs with genomic loci of coding and lncRNA genes that were up- or downregulated during erythroid and megakaryocytic development (Figure 2C). Overall, the genomic loci of all 3 sets of genes were occupied by key hematopoietic TFs at similar frequencies, indicating shared modes of transcriptional regulation. High-stringency lncRNA genes downregulated during erythropoiesis showed a higher level of GATA1 and TAL1 occupancy compared with coding genes. The biological significance of this is unclear and will require further investigation.

To investigate further whether GATA1 regulates erythroid lncRNA genes directly, we examined their expression in G1E-ER4 cells, an immortalized Gata1− erythroblast line expressing an estrogen-activated form of GATA1.13 Treatment of G1E-ER4 cells with β-estradiol triggers a GATA-1–regulated program of gene expression and terminal erythroid maturation. We performed RNA-seq at 0, 3, 7, 14, 24, and 30 hours after β-estradiol treatment and assessed the expression kinetics of genes that were upregulated in erythroblasts as compared with MEPs. Both coding and lncRNA genes whose loci are bound by GATA1 in primary erythroblasts had significantly induced expression by GATA1 activation in G1E-ER4 cells (Figure 2D). In contrast, genes of either type that were upregulated during primary erythropoiesis without being bound by GATA1 were not induced after β-estradiol treatment in G1E-ER4 cells.

We recently demonstrated that megakaryocyte-enriched coding genes, but not erythroid ones, are “primed” in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs).12 Specifically, these genes are occupied in HSPCs by a TF heptad (Gata2, Runx1, Tal1, Fli1, Lmo2, Ldb1, Lyl1, and Erg)27 that facilitates low-level expression. These genes are subsequently activated during megakaryopoiesis and repressed during erythropoiesis, with concomitant lineage-specific alterations in TF occupancy (Figure 2E and Pimkin et al12 ). To determine whether this mechanism applies to hematopoietic lncRNAs, we grouped them according to their expression patterns (megakaryocyte vs MEP and erythroblast vs MEP) and assessed occupancy of the TF heptad at the corresponding genes in the HSPC-like cell line HPC-7.12 For both coding genes and lncRNAs, the highest frequency of heptad occupancy occurred in those that are induced during megakaryopoiesis and either repressed or unchanged during erythropoiesis (Figure 2F). Thus, the model that some megakaryocyte-enriched genes are specifically primed in HSPCs extends to lncRNA loci, emphasizing common regulatory mechanisms with coding genes.

Overall, our findings demonstrate that most erythroid and megakaryocytic polyA+ lncRNAs are transcribed from H3K4me3-rich gene promoters and are regulated by the same key TF networks as coding genes.

Mouse erythroid lncRNAs are poorly conserved in nucleotide sequence and expression in humans

LncRNAs expressed in multiple species are less conserved in primary nucleotide sequence than coding genes.28 We compared the erythroid transcriptome to a phastCons annotation of 5% of the mouse genome most conserved in vertebrates.29 More than half of the spliced mRNA length of coding genes overlapped with phastCons elements (Figure 3A). The degree of overlap for spliced lncRNAs was much lower, although still greater than random, consistent with observations that lncRNAs can have small conserved domains despite low overall interspecies sequence conservation.1 Antisense lncRNAs tended to have relatively higher overlap with phastCons elements, likely reflecting nucleotide conservation of the coding gene on the opposite strand (Figure 3B).

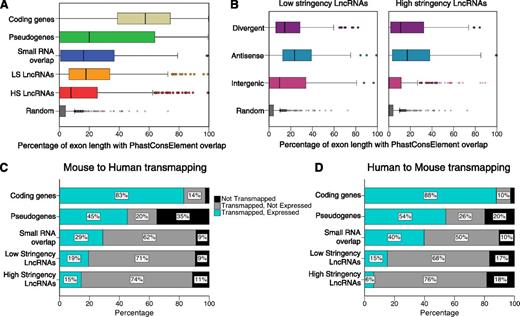

Most lncRNA erythroid genes are not cross-expressed in mice and humans. (A) Boxplots showing the extent to which mature RNAs overlap with PhastConsElements, reflecting DNA sequence conservation in multispecies alignments. The degree of overlap for lncRNA genes is greater than random, but lower than for coding genes. (B) PhastConsElement overlap of lncRNA genes subclassified by orientation relative to coding genes (see Figure 1G). (C) Percentages of mouse erythroid genes transmapping to the human genome and expressed in the human erythroblasts (combined transcriptomes of 5 maturational stages, as detailed in the text). Less than 20% of murine erythroid lncRNA genes are expressed in humans despite identified transmapping orthologous regions for most. (D) Percentages of human erythroid genes transmapping to the mouse genome and expressed in mouse erythroblasts showing low levels of conserved lncRNA expression. HS, high stringency; LS, low stringency.

Most lncRNA erythroid genes are not cross-expressed in mice and humans. (A) Boxplots showing the extent to which mature RNAs overlap with PhastConsElements, reflecting DNA sequence conservation in multispecies alignments. The degree of overlap for lncRNA genes is greater than random, but lower than for coding genes. (B) PhastConsElement overlap of lncRNA genes subclassified by orientation relative to coding genes (see Figure 1G). (C) Percentages of mouse erythroid genes transmapping to the human genome and expressed in the human erythroblasts (combined transcriptomes of 5 maturational stages, as detailed in the text). Less than 20% of murine erythroid lncRNA genes are expressed in humans despite identified transmapping orthologous regions for most. (D) Percentages of human erythroid genes transmapping to the mouse genome and expressed in mouse erythroblasts showing low levels of conserved lncRNA expression. HS, high stringency; LS, low stringency.

Some specific lncRNA genes are noted to not be transcribed across species,30 but few groups have examined this issue globally by comparing transcriptomes.31 To investigate this during erythropoiesis, we performed polyA+ RNA-seq of human umbilical cord blood erythroblasts at defined maturational stages, assembled the combined transcriptome (supplemental Figure 3A), and identified clusters of human coding and lncRNA genes with specific expression kinetics (supplemental Figure 3B). Correlation of human erythroid lncRNA expression with key hematopoietic coding genes may reflect unappreciated regulatory networks. For instance, we identified distinct human lncRNA clusters whose expression kinetics parallel those of mRNA clusters containing GATA1, KLF1, or MYC. These specific lncRNA clusters likely contain candidate effectors for the corresponding TF programs.

Using multispecies genome alignments (UCSC pslMap tool and chain alignments), we identified human orthologous regions for mouse-expressed genes and analyzed human erythroid transcripts produced from these regions. We identified human orthologous regions for >95% of all transcribed mouse genes. As expected, most (∼85%) coding genes expressed in mouse erythroblasts were also expressed in humans. In contrast, <20% of erythroid lncRNA genes expressed in mouse erythroblasts were expressed in matched human cells, even though orthologous regions were identified for ∼90% of these genes (Figure 3C). Transmapping of the human erythroid transcriptome to the mouse genome showed similar results, with most lncRNA genes expressed in humans not being transcribed in mice (Figure 3D). To investigate the possibility that this discrepancy between coding and noncoding genes is due to the low abundance of lncRNA transcripts compared with coding mRNAs, we separately assessed cross-species expression of transcripts with high or low abundance (supplemental Figure 3C-D). Even the most highly expressed lncRNAs (FKPM > 8 in 1 species) were largely not detected in the other species, even though orthologous loci could be identified. These findings demonstrate that most mouse erythroid lncRNA genes are not transcribed in human erythroblasts, and vice versa.

Murine erythroid lncRNAs are conserved between different mouse strains

We investigated the evolution of murine erythroid lncRNAs further by comparing RNA-seq data from splenic erythroblasts of 8 different mouse strains (A/J, AKR/J, BALBc/J, C3H/HeJ, C57BL/6J, CBA/J, DBA/2J, LP/J).15 We quantified the erythroid transcriptome of each strain and examined the cross-strain expression of coding and lncRNAs. Most lncRNAs (>75%) were present in all mouse strains examined, though at a lower percentage than coding genes (>90%) (Figure 4A). On excluding transcripts with the lowest quartile of expression, more than 95% of high-stringency lncRNAs were expressed across mouse species, similar to that of coding genes (Figure 4B). In addition, the expression levels of all transcript types were highly concordant between different mouse strains (Figure 4C) (2-tailed Spearman’s R >0.95 for coding mRNAs, >0.89 for low-stringency lncRNAs, and >0.80 for high-stringency lncRNAs).

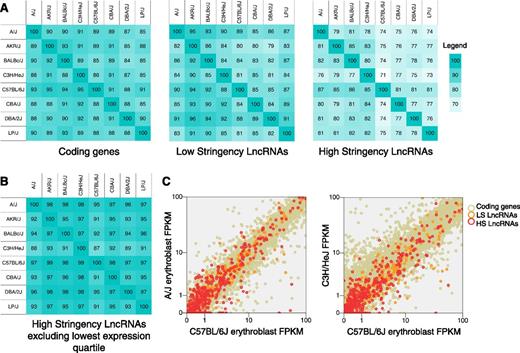

Murine erythroid lncRNAs are largely conserved between different mouse strains. (A) Cross-expression of coding and lncRNA genes in splenic erythroblasts of 8 different mouse strains. Note that lncRNA expression is generally conserved between strains, although at a slightly lower level than coding genes. (B) Similar analysis as in panel A, with lowest expression quartile of lncRNAs excluded, shows more than 95% conserved lncRNA expression between most strains. (C) Comparisons of coding and lncRNA gene expression levels in 2 representative pairs of mouse strains. Note that the expression levels of both lncRNA and coding genes are conserved (2-tailed Spearman’s R >0.95 for coding mRNAs, >0.89 for low-stringency lncRNAs, and >0.80 for high-stringency lncRNAs).

Murine erythroid lncRNAs are largely conserved between different mouse strains. (A) Cross-expression of coding and lncRNA genes in splenic erythroblasts of 8 different mouse strains. Note that lncRNA expression is generally conserved between strains, although at a slightly lower level than coding genes. (B) Similar analysis as in panel A, with lowest expression quartile of lncRNAs excluded, shows more than 95% conserved lncRNA expression between most strains. (C) Comparisons of coding and lncRNA gene expression levels in 2 representative pairs of mouse strains. Note that the expression levels of both lncRNA and coding genes are conserved (2-tailed Spearman’s R >0.95 for coding mRNAs, >0.89 for low-stringency lncRNAs, and >0.80 for high-stringency lncRNAs).

Potential roles for lncRNAs in murine erythroblast maturation

We used RNAi to assess the functions of murine erythroid lncRNAs during in vitro maturation of primary murine erythroblasts.17 We examined candidate lncRNAs that were abundant (FKPM > 4) and erythroid-enriched (at least 4-fold greater expression in fetal liver erythroblasts than MEPs). We included low-stringency lncRNAs as candidates because this group contains some known lncRNAs. We selected 11 conserved (orthologous transcripts detected in human erythroblasts) and 16 nonconserved (orthologous transcripts not detected) lncRNA candidates (supplemental Table 2). Expression analysis using a custom microarray (supplemental Figure 2A-C, above) confirmed that these genes were also enriched in adult bone marrow erythroblasts and upregulated a median of 41-fold (range: 2- to 2054-fold) relative to multipotent progenitors (Figure 5). Thus, the candidate lncRNAs selected for further study are abundant and erythroid-enriched.

Mouse lncRNAs selected for RNAi studies. Twenty-seven lncRNAs were selected according to criteria described in the text. The relative expression of these lncRNAs in purified hematopoietic lineages from adult mouse bone marrow was determined using a custom oligonucleotide array and is shown graphically. “Conserved” refers to the presence of assembled orthologous transcripts detected in human erythroblasts (Figure 3C). Candidate erythroid lncRNAs shown here are upregulated 2- to 2054-fold (median 41-fold) in erythroblasts compared with multipotent progenitors. Names assigned to lncRNAs that potentially function in erythropoiesis according to RNAi studies in Figure 6 are indicated. Lnc051 was previously named “Lincred1.”32 Ggnbp2os was not detectable in primary human erythroblasts, but transcription cannot be ruled out in human K562 erythroleukemia cells (supplemental Figure 8). CMP, common myeloid progenitor; EE, early erythroblast; Expr, absolute expression level by microarray; GMP, granulocyte macrophage progenitor; GR, granulocyte; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; LE, late erythroblast.

Mouse lncRNAs selected for RNAi studies. Twenty-seven lncRNAs were selected according to criteria described in the text. The relative expression of these lncRNAs in purified hematopoietic lineages from adult mouse bone marrow was determined using a custom oligonucleotide array and is shown graphically. “Conserved” refers to the presence of assembled orthologous transcripts detected in human erythroblasts (Figure 3C). Candidate erythroid lncRNAs shown here are upregulated 2- to 2054-fold (median 41-fold) in erythroblasts compared with multipotent progenitors. Names assigned to lncRNAs that potentially function in erythropoiesis according to RNAi studies in Figure 6 are indicated. Lnc051 was previously named “Lincred1.”32 Ggnbp2os was not detectable in primary human erythroblasts, but transcription cannot be ruled out in human K562 erythroleukemia cells (supplemental Figure 8). CMP, common myeloid progenitor; EE, early erythroblast; Expr, absolute expression level by microarray; GMP, granulocyte macrophage progenitor; GR, granulocyte; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; LE, late erythroblast.

We designed 4 shRNAs against each candidate lncRNA (supplemental Table 3) and cloned them into a retroviral vector that co-expresses GFP. Primary murine fetal liver erythroblasts (embryonic day 14.5) were isolated by immunomagnetic bead selection, infected with the shRNA retroviruses, and cultured for 2 days in medium that supports progenitor expansion. After 48 hours, the cells were switched to an erythropoietin-containing medium that supports terminal maturation to the anucleate reticulocyte stage.33 For 21 of the 27 targeted lncRNAs, at least 1 shRNA was identified that suppressed target expression by more than 40% (supplemental Table 4). Nonetheless, the expression of only 10 lncRNAs could be suppressed by more than 75%, demonstrating a limitation of RNAi in the study of lncRNAs. We performed functional analyses on the 21 lncRNAs with at least 40% knockdown of expression.

We assessed the maturation of lncRNA-deficient erythroblasts into reticulocytes by flow cytometry analysis after staining with Hoechst 33342, a cell-permeable DNA dye. During pilot studies, we observed that infection of erythroblasts with control retroviruses at high multiplicity of infection >2-3) could produce nonspecific maturation defects (not shown). Therefore, we infected progenitors at a multiplicity of infection of 1-2, resulting in 30% to 70% GFP+ cells. We assessed maturation of erythroblasts into reticulocytes in infected cells by flow cytometry using a gating strategy that was optimized for sensitivity and specificity through the use of multiple positive (Gata1 or Fog1 shRNAs) and negative (vector or luciferase shRNA) controls (supplemental Figure 4A-B). We identified 1 low-stringency and 6 high-stringency lncRNAs whose knockdown by at least 2 different shRNAs inhibited enucleation by >25% (Figure 6A-B, supplemental Figure 4C). Of these, Lnc051 was annotated previously as “Lincred1,”32 whereas the others were either unannotated or unnamed transcripts. We named the other 6 genes with potential function as described in Figure 5 and supplemental Methods. Erythroid development is accompanied by downregulation of surface CD44 and reduced cell size (assessed by forward scatter).34 At 48 hours, knockdown of 2 lncRNAs (Erytha and Scarletltr) showed reduced proportions of late stage (CD44low forward scatterlow) erythroblasts consistently using 2 different shRNAs that target different regions of the same transcript (Figure 6C-D; supplemental Figure 5). Thus, we have identified 7 previously uncharacterized lncRNAs with potential roles in terminal erythroid maturation.

RNAi of multiple mouse lncRNA genes inhibits erythroblast maturation. (A) Mouse fetal liver erythroid progenitors were infected with retroviruses encoding shRNAs against lncRNAs, cultured for 48 hours in an expansion medium to maintain the immature state, and then switched to a medium that facilitates terminal maturation. Representative flow cytometry plots quantifying the proportion of anucleate reticulocytes (black rectangles) after 48 hours of maturation are shown. Hoechst 33342 is a cell permeable nuclear dye. Ter119 is an erythroid maturation marker. (B) Summary of multiple experiments showing percentage of reticulocytes in shRNA-expressing erythroid cultures after 48 hours of maturation, performed as shown in panel A. Vector-only and shLuciferase shRNAs are negative controls; shGATA1 and shFOG1 shRNAs are positive controls used to suppress expression of the essential erythroid TFs. The results of 2 different shRNAs used to knockdown each candidate are shown as pairs of bars for each lncRNA. n = 3 biological replicates. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots assessing the maturation stages of nucleated (Hoechsthigh) erythroblasts at 48 hours of maturation, using the immature erythroblast marker CD44 and forward scatter (FSC), which reflects cell size. Gates (from highest to lowest) mark early-, middle-, and late-stage erythroblasts; the percentage of cells in the late stage gate is listed. (D) Summary of multiple experiments showing maturation stage distribution of nucleated erythroblasts in shRNA-expressing erythroid cultures at 24 and 48 hours, performed as shown in panel C. Knockdown of 2 lncRNAs (Erytha and Scarletltr, dotted black rectangles) reduced the proportion of mature erythroblasts by >25% at 48 hours by 2 different shRNAs. n = 3 biological replicates. (E) Single molecule RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) on primary mouse fetal liver erythroblasts for Cyclin A2 mRNA and for lncRNAs Bloodlinc, Galont, Redrum, and Lincred1. Single-slice images depict subcellular localization; composite images depict overall lncRNA abundance. Each composite image represents a maximum projection of a stack of z-slices taken through the volume of the cell. The nucleus is labeled blue with 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole, and single RNA molecules are visible as white punctate spots.

RNAi of multiple mouse lncRNA genes inhibits erythroblast maturation. (A) Mouse fetal liver erythroid progenitors were infected with retroviruses encoding shRNAs against lncRNAs, cultured for 48 hours in an expansion medium to maintain the immature state, and then switched to a medium that facilitates terminal maturation. Representative flow cytometry plots quantifying the proportion of anucleate reticulocytes (black rectangles) after 48 hours of maturation are shown. Hoechst 33342 is a cell permeable nuclear dye. Ter119 is an erythroid maturation marker. (B) Summary of multiple experiments showing percentage of reticulocytes in shRNA-expressing erythroid cultures after 48 hours of maturation, performed as shown in panel A. Vector-only and shLuciferase shRNAs are negative controls; shGATA1 and shFOG1 shRNAs are positive controls used to suppress expression of the essential erythroid TFs. The results of 2 different shRNAs used to knockdown each candidate are shown as pairs of bars for each lncRNA. n = 3 biological replicates. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots assessing the maturation stages of nucleated (Hoechsthigh) erythroblasts at 48 hours of maturation, using the immature erythroblast marker CD44 and forward scatter (FSC), which reflects cell size. Gates (from highest to lowest) mark early-, middle-, and late-stage erythroblasts; the percentage of cells in the late stage gate is listed. (D) Summary of multiple experiments showing maturation stage distribution of nucleated erythroblasts in shRNA-expressing erythroid cultures at 24 and 48 hours, performed as shown in panel C. Knockdown of 2 lncRNAs (Erytha and Scarletltr, dotted black rectangles) reduced the proportion of mature erythroblasts by >25% at 48 hours by 2 different shRNAs. n = 3 biological replicates. (E) Single molecule RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) on primary mouse fetal liver erythroblasts for Cyclin A2 mRNA and for lncRNAs Bloodlinc, Galont, Redrum, and Lincred1. Single-slice images depict subcellular localization; composite images depict overall lncRNA abundance. Each composite image represents a maximum projection of a stack of z-slices taken through the volume of the cell. The nucleus is labeled blue with 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole, and single RNA molecules are visible as white punctate spots.

We investigated the cellular localization of lncRNAs with the strongest knockdown phenotypes using RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization. Probe sets against 4 of 5 lncRNAs examined (Bloodlinc, Galont, Redrum, Lincred1) produced unambiguous signals in primary mouse fetal liver erythroblasts (Figure 6E). Single-slice confocal images were used to identify subcellular localization and composite images to assess overall lncRNA abundance. Probes against CyclinA2 mRNA used as a positive control showed cytoplasmic localization. Redrum RNA was largely cytoplasmic, whereas Bloodlinc and Galont were pancellular. Lincred1 was largely nuclear and displayed occasional bright sites of active transcription or accumulation. Our observation that individual lncRNAs exhibit distinct localization patterns suggests different mechanisms of action.

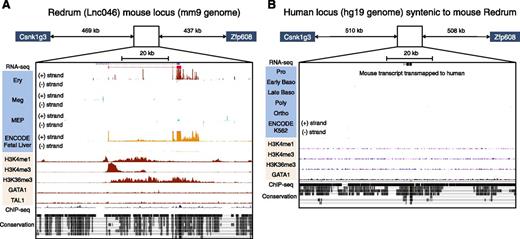

Functional mouse erythroid lncRNAs are not expressed in human erythroblasts

Six of the 7 erythroid lncRNAs with potential functions identified by RNAi were not expressed in human erythroblasts, even though orthologous genomic loci were identified by transmapping. We compared the transcriptional and epigenetic features at these loci in mouse and human erythroid cells (Figure 7; supplemental Figures 6-8). The mouse loci were marked by robust RNA-seq signals, indicating gene expression both by our erythroblast RNA-seq and ENCODE mouse fetal liver RNA-seq.37 They also showed marks of active chromatin and, in 5 of 7 cases, GATA1/TAL1 occupancy. In contrast, for 6 of these loci, no RNA-seq transcripts were evident in the mapped orthologous human loci by de novo RNA-seq assembly or by visual inspection of mapped reads of 5 distinct stages of human erythroblasts defined by flow cytometry.14 In some of these transcriptionally silent human loci, no marks of active chromatin were observed (see Figure 7A-B for Redrum, supplemental Figure 6A-B for Galont), whereas for others, histone marks and TF occupancy peaks were present without any mapped RNA-seq reads (see supplemental Figure 6C-D for Erytha, supplemental Figure 7A-B for Lincred1, supplemental Figure 7C-D for Scarletltr, and supplemental Figure 8A-B for Bloodlinc). For Ggnbp2os (antisense to the coding gene Ggnbp2), no assembled transcript was identifiable in human erythroblasts, although human K562 RNA-seq tracks showed some reads mapping to the strand antisense to Ggnbp2, so human transcription cannot be ruled out. Thus, for 6 of 7 lncRNAs with potential functions in erythropoiesis indicated by RNAi, we found no evidence for expression of the orthologous human loci multiple RNA-seq datasets derived from primary human erythroblasts, K562 erythroleukemia cells, or any other nonerythroid cell line or primary tissue analyzed by ENCODE (not shown). Our mouse and human RNA-seq datasets were of similar depth (more than 100 million reads per sample), and the lncRNAs were expressed relatively robustly in mouse erythroblasts (median FPKM 13, range 4 to 312). Therefore, failure to detect orthologous human transcripts cannot be attributed to differences in the depth of sequencing or low abundance.

The mouse erythroid lncRNA Redrum is not expressed in human erythroblasts. UCSC Genome browser35 images of the mouse Redrum (Lnc046) locus (A) and the orthologous human region (B). Images for RNA-seq studies, histone modifications, and TF binding in erythroid cells are indicated. Note that active transcription (RNA-seq) and histone H3 chromatin marks occur in mice, but not humans. H3K4me3 marks the active promoter and H3K36me3 marks DNA polymerase II elongation. Mouse RNA-seq tracks are from primary fetal liver (Ter119+) erythroblasts, CD41+ megakaryocytes cultured from primary fetal liver erythroblasts, fluorescent-activated cell sorting–purified MEPs (all from this study), and mouse fetal liver erythroblasts analyzed by ENCODE. Mouse ChIP-seq tracks are from fetal liver (Ter119+) erythroblasts. Human RNA-seq tracks are from umbilical cord blood CD34+-derived erythroid cultures fractionated by flow cytometry into 5 different stages (pro, early basophilic, late basophilic, polychromatophilic, and orthochromatic erythroblasts).14 Histone modifications tracks are from ENCODE K562 erythroleukemia cells36 ; the GATA1 track is from ENCODE peripheral blood–derived erythroblasts.35

The mouse erythroid lncRNA Redrum is not expressed in human erythroblasts. UCSC Genome browser35 images of the mouse Redrum (Lnc046) locus (A) and the orthologous human region (B). Images for RNA-seq studies, histone modifications, and TF binding in erythroid cells are indicated. Note that active transcription (RNA-seq) and histone H3 chromatin marks occur in mice, but not humans. H3K4me3 marks the active promoter and H3K36me3 marks DNA polymerase II elongation. Mouse RNA-seq tracks are from primary fetal liver (Ter119+) erythroblasts, CD41+ megakaryocytes cultured from primary fetal liver erythroblasts, fluorescent-activated cell sorting–purified MEPs (all from this study), and mouse fetal liver erythroblasts analyzed by ENCODE. Mouse ChIP-seq tracks are from fetal liver (Ter119+) erythroblasts. Human RNA-seq tracks are from umbilical cord blood CD34+-derived erythroid cultures fractionated by flow cytometry into 5 different stages (pro, early basophilic, late basophilic, polychromatophilic, and orthochromatic erythroblasts).14 Histone modifications tracks are from ENCODE K562 erythroleukemia cells36 ; the GATA1 track is from ENCODE peripheral blood–derived erythroblasts.35

Discussion

RNA profiling of cell lines and primary tissues has discovered thousands of mammalian lncRNAs.38 We identified 1109 candidate lncRNAs in erythroblasts, megakaryocytes, and MEPs, more than half of which were not annotated in gene databases. Given the exquisite lineage specificity of lncRNAs (this report and Calibi et al39 ), it is likely that additional new ones will be discovered through transcriptome analysis of other specialized cell types. Our current findings identify a cohort of lncRNAs that potentially regulate erythropoiesis and also generate new insights into lncRNA biology in general.

Orthologous lncRNA genes that are expressed in multiple species are known to have less conservation of primary nucleotide sequence compared with coding genes.1 By directly comparing transcriptomes, we demonstrate an even more radical lack of evolutionary conservation. Specifically, more than 80% of mouse erythroid lncRNAs, including the most highly expressed ones, are not detected in human erythroblasts of similar developmental and maturational stages, and most human erythroid lncRNAs are not detected in mice. This feature of lncRNA evolution is noted in a few studies,30,31 but not generally appreciated or tested systematically. Moreover, our findings are consistent with findings from the Mouse ENCODE Consortium (manuscript in revision) that lncRNAs are far more species-specific than coding genes. The ENCODE group compared RNA-seq datasets predominantly derived from murine primary cells against human cell lines. Our approach refines and extends these general comparisons by focusing on a set of matched cell types generated from primary tissues and demonstrates that human and mouse tissues produce largely distinct repertoires of lncRNAs.

Few studies compare the transcriptomes of matched cells from different species to investigate the actual expression of orthologous lncRNA genes. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to perform de novo assembly of lncRNAs in matched hematopoietic cell types (erythroblasts) of mice and humans, compare the transcriptomes, and demonstrate lack of cross-species transcription definitively for most lncRNAs.

It is possible that different lncRNAs have converged in evolution to regulate common sets of genes in different species. However, recent studies reveal a surprising number of differences in the levels and stage specificity of protein-coding mRNAs between human and mouse erythroblasts (Patrick Gallagher, X.A., and N.M., manuscript submitted January 2014). These findings may arise at least partly from interspecies differences in lncRNAs that regulate gene expression. It should be possible to test this as sets of murine and human lncRNA regulated genes become defined in the future.

There is lively debate over what proportion of the lncRNA transcriptome mediates biological functions as opposed to representing inert “transcriptional noise.”3 Our finding that knockdown of 7 lncRNAs impairs the maturation of primary erythroblasts provides preliminary evidence that at least a subset may have biological functions, in agreement with recent studies.8,11 Indeed, 4 of the lncRNAs implicated in erythroid maturation by our RNAi studies (Bloodlinc, Galont, Redrum, Lincred1; Figure 6) were also found by Alvarez-Dominguez et al to be functional using independent sets of shRNAs in a similar assay.11 These well-controlled RNAi experiments identify overlapping sets of candidate lncRNAs that may facilitate erythropoiesis. However, their biological functions must now be determined definitively through additional investigations, including in vivo gene ablation and identification of relevant interacting genes and/or proteins.

Six of the 7 lncRNAs identified by the current study to have potential roles in erythropoiesis showed no evidence of transcription in human erythroblasts, indicating that conserved interspecies expression of lncRNAs does not necessarily correlate with function. In agreement, Braveheart, an lncRNA required for cardiac development in mice, is not expressed in rats or humans.30 We extend this example by reporting multiple other lncRNAs that potentially function in tissue development and yet are not expressed across mammalian species. New RNAs form constantly during evolution40 and can arise even from a single nucleotide replacement.41 The evolution of novel proteins from these transcripts likely requires a relatively stringent set of criteria to allow the formation of a functional peptide chain. In contrast, functional lncRNAs likely evolve relatively rapidly through the formation of nucleotide permutations that form protein- and nucleic acid–interacting motifs.42 Our data, if combined with RNA-seq from appropriately matched erythroblasts of other mammals, may illuminate further the evolution of these lncRNAs and stratify their ancestry along the 70-million-year timeline since human and mouse ancestors diverged.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Moran Cabili for custom PfamAnalysis scripts, Doug Higgs for helpful discussions and access to unpublished data, Mike Lin for assistance with PhyloCSF, Merav Socolovsky for guidance with flow cytometry analysis, and Harvey Lodish and members of his laboratory, Wenqian Hu and Juan Alvarez-Dominguez, for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the American Society of Hematology (ASH) Research Training Award for Fellows (V.R.P.); ASH Scholar Award (V.R.P.); UPenn Measey Fellowship Award (V.R.P.); National Institutes of Health Common Fund, New Innovator (1DP2OD008514) (M.D., A.R.); Burroughs-Wellcome Fund Career Award at the Scientific Interface (M.D., A.R.); National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK32094) (N.M.); National Institutes of Health, National Human Genome Research Institute Intramural funds (D.M.B.); National Institutes of Health, National Human Genome Research Institute (1RC2HG005573) (R.C.H.); National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK065806) (R.C.H.) and (DK092318-01 and P30DK090969) (M.J.W.); The Roche Foundation for Anemia Research (M.J.W.); and the National Science Foundation (OCI-0821527, for instrumentation).

Authorship

Contribution: V.R.P., T.M., D.M.B., R.C.H., and M.J.W. designed the research; V.R.P., J.L., Y.Y., D.S., and N.K. performed experiments; T.M., M.P., R.C.H., X.A., and N.M. performed high-throughput sequencing; V.R.P., T.M., and A.V.K. analyzed bioinformatic data; M.G. wrote a script for bioinformatic analysis; S.M.A. and D.M.B. performed cell sorting; M.D. and A.R. performed RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization and imaging; V.R.P., T.M., and M.J.W. wrote the manuscript; and M.P., N.M., D.M.B., and R.C.H. edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mitchell J. Weiss, Division of Hematology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, The Abramson Research Center 316B, 3615 Civic Center Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104-4318; e-mail: weissmi@email.chop.edu.