Key Points

Bortezomib-induction/Mel100-ASCT/lenalidomide consolidation-maintenance is effective in elderly patients with excellent performance status.

Deaths related to AEs were higher in patients ≥70 years, suggesting the need of a more careful patient selection.

Abstract

A sequential approach including bortezomib induction, intermediate-dose melphalan, and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), followed by lenalidomide consolidation-maintenance, has been evaluated. Efficacy and safety data have been analyzed on intention-to-treat and results updated. Newly diagnosed myeloma patients 65 to 75 years of age (n = 102) received 4 cycles of bortezomib-pegylated liposomal doxorubicin-dexamethasone, tandem melphalan (100 mg/m2) followed by ASCT (MEL100-ASCT), 4 cycles of lenalidomide-prednisone consolidation (LP), and lenalidomide maintenance (L) until disease progression. The complete response (CR) rate was 33% after MEL100-ASCT, 48% after LP and 53% after L maintenance. After a median follow-up of 66 months, median time-to-progression (TTP) was 55 months and median progression-free survival 48 months. Median overall survival (OS) was not reached, 5-year OS was 63%. In CR patients, median TTP was 70 months and 5-year OS was 83%. Median survival from relapse was 28 months. Death related to adverse events (AEs) occurred in 8/102 patients during induction or transplantation. Rate of death related to AEs was higher in patients ≥70 years compared with younger (5/26 vs 3/76, P = .024). Bortezomib-induction followed by ASCT and lenalidomide consolidation-maintenance is a valuable option for elderly myeloma patients, with the greatest benefit in those younger than 70 years of age.

Introduction

The outcome of multiple myeloma (MM) patients significantly improved after the introduction of novel agents.1 In patients younger than 65 years of age, induction treatment with bortezomib-dexamethasone (VD) showed increased postinduction and posttransplantation with at least very good partial response (VGPR) rates compared with vincristine-doxorubicin-dexamethasone (VAD).2 The addition of a third drug to VD further improved response rates. VD plus thalidomide (VTD) induction therapy before double autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) significantly improved rate of complete or near complete response (CR/nCR) compared with thalidomide-dexamethasone.3 Similarly, VD plus doxorubicin significantly increased pre- and posttransplantation response rate compared with VAD.4

In a randomized trial, high-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared with conventional chemotherapy,5 but patients enrolled in this study did not receive any novel agent up front. A recent randomized study compared full-dose melphalan (melphalan 200 mg/m2 [Mel200]) followed by ASCT (Mel200-ASCT) with melphalan-prednisone-lenalidomide. A significant PFS advantage was reported for patients who received Mel200-ASCT, confirming the role of high-dose chemotherapy and ASCT in the era of novel agents.6 Mel200-ASCT prolonged PFS compared with intermediate-dose melphalan (melphalan 100 mg/m2 [Mel100]) followed by ASCT (Mel100-ASCT) in patients younger than 65 years of age.7 In elderly patients, conflicting results were reported with Mel100-ASCT. One study showed that Mel100-ASCT was as effective as melphalan-prednisone (MP) in patients aged 65 to 75 years.8 In another study, Mel100-ASCT was superior to MP in patients ages 65 to 70 years.9

Two recent studies showed increased PFS for patients who received posttransplantation lenalidomide maintenance compared with patients who did not.10,11 Only in 1 trial did prolonged PFS translated into an OS advantage.10 In elderly MM patients the association of melphalan-prednisone-lenalidomide followed by lenalidomide maintenance improved PFS compared with MP; the PFS improvement could be mainly attributed to maintenance.12 Recently, the association of bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone-thalidomide followed by bortezomib-thalidomide maintenance induced longer PFS and OS than bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone; the major impact on survival was determined by continuous therapy.13

This phase 2 trial investigated the safety and efficacy of a sequential approach including a 3-drug bortezomib-based induction, intermediate-dose melphalan (Mel100), and ASCT followed by a lenalidomide-based consolidation-maintenance treatment in elderly patients eligible for transplantation. After a median follow-up of 66 months, an updated analysis was performed to evaluate long-term efficacy and safety.

Methods

As previously reported, between October 2005 and July 2007, 102 patients were enrolled in 17 Italian centers. Key eligibility criteria included newly diagnosed MM patients, with measurable disease, 65 to 75 years of age or younger but ineligible for high-dose therapy. The institutional review boards of the participating centers approved the study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial was registered on EudraCT registry, identifier 2005-004714-32. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study design and treatment

Study details have been previously reported.14 Briefly, in this multicenter, noncomparative, open-label, phase 2 study, patients received induction with 4 21-day bortezomib-pegylated liposomal doxorubicin-dexamethasone (PAD) cycles (bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11; pegylated liposomal doxorubicin 30 mg/m2 on day 4; and dexamethasone 40 mg on days 1 to 4, 8 to 11, and 15 to 18 in cycle 1 and on days 1 to 4 in cycles 2 to 4). Cyclophosphamide (3 g/m2) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor were used to mobilize stem cells. Melphalan was administered twice at the dose of 100 mg/m2 followed by ASCT (Mel100-ASCT). Patients without progressive disease (PD) at 2 to 4 months after the second ASCT received 4 28-day consolidation cycles with lenalidomide (25 mg/day on days 1 to 21) plus prednisone (LP; 50 mg every other day) followed by lenalidomide alone (L; 10 mg/d on days 1 to 21) as maintenance treatment until disease progression.

Assessment

Efficacy was assessed every 4 weeks. Safety was assessed every 2 weeks during LP consolidation and monthly during maintenance. Treatment response was monitored using the standard International Myeloma Working Group Uniform Response Criteria.15 Time-to-progression (TTP) was defined as time from enrollment until progression or relapse; deaths as a result of causes other than progression were censored. PFS was defined as time from enrollment until the date of progression, relapse, or death from any cause (whichever occurred first). OS was defined as time from enrollment until the date of death or the date the patient was last known to be alive.15 All adverse events (AEs) were assessed at each visit and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 3).16

End points and statistical analysis

The study was designed using Fleming’s method17 with a 1-sided type I error of 0.05 and statistical power of 80%. The expected complete response (CR) rate with the experimental treatment was 25%; the CR rate with standard treatment was 15%. Primary end points were safety (grade 4 neutropenia for >7 days, any other grade 4 hematologic toxicity, and any grade >3 nonhematologic toxicity in <30% of patients) and efficacy (CR rate ≥15% after PAD-MEL100 and >25% after LP-L). Secondary end points were PFS and OS. All patients meeting eligibility criteria who had started the first cycle of PAD therapy were evaluated for toxicity, response, and survival on an intention-to-treat basis. Raw incidence of toxicity according to treatment phase was reported; patients who presented the same type of toxicity in different treatment phases were counted only once. Time-to-event estimates were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method.18 PFS and OS were also analyzed by univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models, comparing the 2 arms by the Wald test and calculating 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The following variables were assessed for potential association with PFS and OS: age at diagnosis (≥70 vs <70 years); International Staging System (ISS) stages combined with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) abnormalities (ISS_FISH group I [ISS stage I/II and absence of t(4;14) and del17] vs ISS_FISH group II [ISS stage I plus presence of t(4;14) or del17; ISS stage III, absence of t(4;14) and del17] vs ISS_FISH group III [ISS Stage II/III plus presence of t(4;14) or del17)]19 ; best response achieved (CR vs VGPR vs partial response [PR] stable disease [SD]). Best response was always treated as a time-dependent variable. All reported P values were 2-sided, at the conventional 5% significance level. Analyses were performed using SAS software, version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R 3.0.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), www.r-project.org. Times of observation were censored on October 15, 2012.

Results

Patients

A total of 102 patients have been enrolled. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were previously reported.14 Median age was 67 years (range 46 to 74 years), 26% of patients were older than 70 years, and 32 patients were younger than 65 years of age but considered not eligible for full-dose melphalan and ASCT. The main reasons for transplant ineligibility were renal impairment (45%), cardiovascular disease (20%), chronic pulmonary disease (10%), previous neoplasia (10%), diabetes (10%), and gastrointestinal disease (5%). Regarding prognostic factors, among patients for whom both ISS and FISH data were available, 61% had ISS I/II and absence of t(4;14)/del17; 22% ISS stage I plus presence of t(4;14)/del17 or ISS stage III and absence of t(4;14)/del17; and 17% ISS stage II/III plus presence of t(4;14) or del17.

At the time of analysis, 10 patients had died during treatment and 30 patients had discontinued therapy (toxicity, n = 22; withdrawal of consent, n = 4; insufficient stem-cell harvest, n = 2; second primary malignancies, n = 2). At the last follow-up, 37 patients had discontinued treatment due to PD, 3 patients were lost at follow-up, and 22 patients were still receiving maintenance. Of 102 patients who started PAD induction, 97 received at least 3 cycles and 92 entered the cyclophosphamide and MEL100 phase. Of these patients, 83 received MEL100-ASCT. Of 80 patients who completed the transplant phase, 73 received at least 3 LP cycles, and 66 patients started maintenance.

Response

In the intention-to-treat analysis, after PAD induction 56/102 patients (55%) achieved at least VGPR, including 12 (12%) in CR; after Mel100-ASCT, 78 patients (76%) obtained at least VGPR, including 34 (33%) in CR. After LP consolidation, 82 patients (80%) achieved at least VGPR, including 49 (48%) in CR. After L maintenance (median duration 27 months), 84 patients (82%) obtained at least VGPR, including 54 (53%) in CR (Table 1). During LP consolidation, 17 patients upgraded their posttransplantation response (1 patient in SD achieved PR, 2 patients in PR achieved VGPR, and 3 patients in PR/VGPR achieved CR). During L maintenance, 7 patients improved their postconsolidation response (2 patients in SD/PR achieved VGPR and 5 patients in VGPR obtained CR). No specific baseline features able to predict CR were observed, and patients with high-risk disease had similar CR rate compared with standard-risk patients.

Best response according to treatment phase (intention-to-treat analysis)

| . | PAD (n = 102) . | PAD-MEL100-ASCT (n = 102) . | PAD-MEL100-ASCT-LP (n = 102) . | PAD-MEL100-ASCT-LP-L (n = 102) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR or VGPR | 56 (55%) | 78 (76%) | 82 (80%) | 84 (82%) |

| CR | 12 (12%) | 34 (33%) | 49 (48%) | 54 (53%) |

| VGPR | 44 (43%) | 44 (43%) | 33 (32%) | 30 (29%) |

| PR | 34 (33%) | 17 (17%) | 14 (14%) | 13 (13%) |

| SD | 11 (11%) | 6 (6%) | 5 (5%) | 4 (4%) |

| PD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NA | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| . | PAD (n = 102) . | PAD-MEL100-ASCT (n = 102) . | PAD-MEL100-ASCT-LP (n = 102) . | PAD-MEL100-ASCT-LP-L (n = 102) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR or VGPR | 56 (55%) | 78 (76%) | 82 (80%) | 84 (82%) |

| CR | 12 (12%) | 34 (33%) | 49 (48%) | 54 (53%) |

| VGPR | 44 (43%) | 44 (43%) | 33 (32%) | 30 (29%) |

| PR | 34 (33%) | 17 (17%) | 14 (14%) | 13 (13%) |

| SD | 11 (11%) | 6 (6%) | 5 (5%) | 4 (4%) |

| PD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NA | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

Percentage may not total 100 because of rounding.

NA, not available; SD, stable disease.

Survival

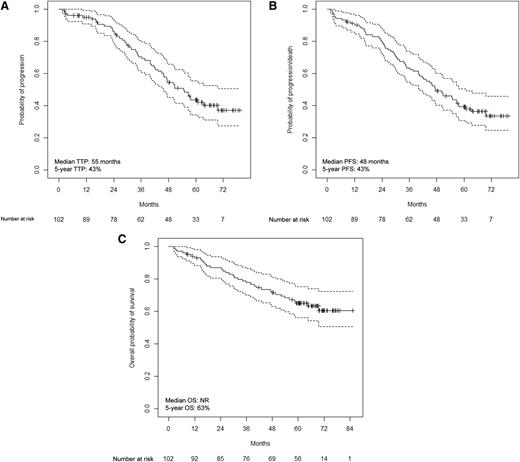

Median follow-up was 66 months. In the intention-to-treat population, median TTP was 55 months and 5-year TTP was 43% (Figure 1A). Median PFS was 48 months and 5-year PFS was 43% (Figure 1B). Median OS was not reached and 5-year OS was 63% (Figure 1C). The discrepancy between TTP and PFS was mainly related to the occurrence of deaths related to AEs.

Survival in all patients. (A) Time to progression; (B) progression-free survival; (C) and overall survival.

Survival in all patients. (A) Time to progression; (B) progression-free survival; (C) and overall survival.

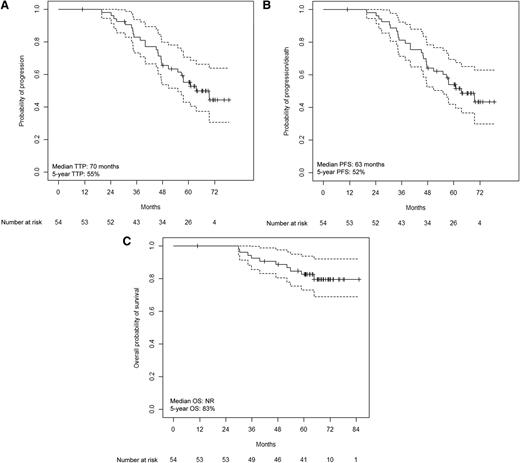

In patients who achieved CR, median TTP was 70 months (Figure 2A) and median PFS was 63 months (Figure 2B), median OS was not reached, and 5-year OS was 83% (Figure 2C).

Survival in CR patients. (A) Time to progression in patients who achieved CR; (B) progression-free survival in patients who achieved CR; (C) and overall survival in patients who achieved CR.

Survival in CR patients. (A) Time to progression in patients who achieved CR; (B) progression-free survival in patients who achieved CR; (C) and overall survival in patients who achieved CR.

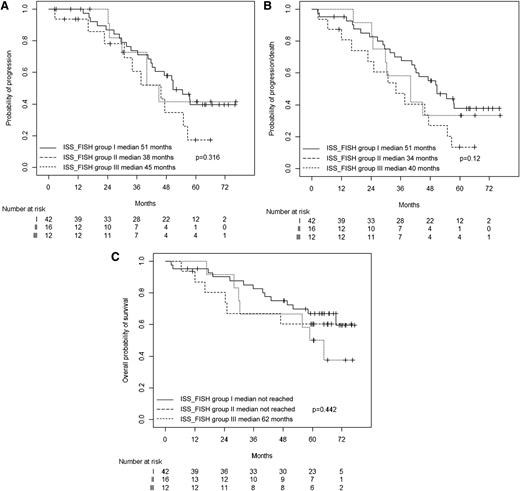

Figure 3 shows TTP (panel A), PFS (panel B), and OS (panel C) for patients included in the 3 ISS_FISH groups.

Combined ISS and FISH. (A) Time to progression; (B) progression-free survival; (C) and overall survival.

Combined ISS and FISH. (A) Time to progression; (B) progression-free survival; (C) and overall survival.

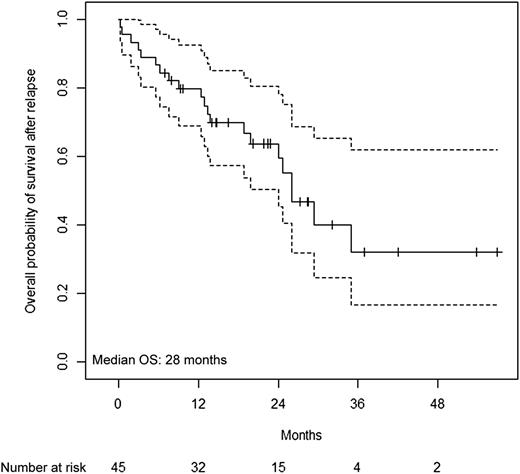

At data cutoff, 52 patients relapsed and 45 patients had received subsequent therapy. Seventeen patients received bortezomib-based therapy, 14 patients received immunomodulatory drugs (lenalidomide, n = 6; thalidomide, n = 7; pomalidomide, n = 1), and 14 patients received chemotherapy or another experimental therapy. At least SD was achieved in 70% of patients, including 48% PR and 19% CR. Median OS from relapse was 28 months (Figure 4).

In multivariate analysis, the ISS_FISH group I was associated with prolonged PFS compared with ISS_FISH II (hazard ratio [HR] 0.43; 95% CI 0.21-0.87, P = .019) as well as compared with ISS_FISH III (HR 0.5, 95% CI 0.21-1.20, P = .118). Achieving CR was associated with significantly prolonged PFS compared with achieving VGPR only (HR 0.06, 95% CI 0.01-0.33, P < .001). No significant association between age and PFS was noticed. Similarly, ISS_FISH group I was associated with prolonged OS compared with ISS_FISH II (HR 0.40; 95% IC 0.15-1.15, P = .007) and compared with ISS_FISH III (HR 0.25, 95% CI 0.09-0.68, P = .81). Achieving CR was associated with significantly prolonged OS compared with achieving VGPR only (HR 0.05, 95% CI 0.01-0.33, P = .003). No association between age and OS was reported.

Safety

Eight patients died resulting from AEs: 3 during the PAD induction (diverticulitis, n = 1; septic shock, n = 1; central nervous system bleeding, n = 1) and 5 during Mel100-ASCT (septic shock, n = 2; pneumonia, n = 2; and pulmonary embolism, n = 1). No death related to AEs has been reported during consolidation or maintenance (1 patient died for an unknown reason and 1 patient died because of PD). The frequency of death related to AEs was significantly higher in patients older than 70 years than in younger patients (19% vs 5%, P = .024) (Table 2).

Discontinuation for adverse events or death related to adverse events in all patients and according to age

| . | All patients (n = 102) . | Patients age < 70 (n = 76) . | Patients age ≥ 70 (n = 26) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discontinuation for AEs or death related to AEs | 30 (29%) | 20 (26%) | 10 (38%) |

| AEs | 22 (22%) | 17 (22%) | 5 (19%) |

| Death related to AEs | 8 (8%) | 3 (5%)* | 5 (19%)* |

| . | All patients (n = 102) . | Patients age < 70 (n = 76) . | Patients age ≥ 70 (n = 26) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discontinuation for AEs or death related to AEs | 30 (29%) | 20 (26%) | 10 (38%) |

| AEs | 22 (22%) | 17 (22%) | 5 (19%) |

| Death related to AEs | 8 (8%) | 3 (5%)* | 5 (19%)* |

P value (Fisher exact test .024).

Table 3 shows the raw incidence of the main grade 3-4 AEs. Hematologic AEs included thrombocytopenia (91%) and neutropenia (90%). Nonhematologic AEs included infections (33%), peripheral neuropathy (18%), gastrointestinal AEs (18%), dermatologic toxicity (10%), and thromboembolism (7%).

Raw incidence of grade 3-4 adverse events according to treatment phase (intention-to-treat analysis)

| . | PAD (n = 102) . | PAD-MEL100-ASCT (n = 102) . | PAD-MEL100-ASCT-LP (n = 102) . | PAD-MEL100-ASCT-LP-L (n = 102) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematological | ||||

| Anemia | 3 (3%) | 16 (16%) | 16 (16%) | 16 (16%) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 17 (17%) | 89 (87%) | 93 (91%) | 93 (91%) |

| Neutropenia | 10 (10%) | 90 (88%) | 91 (89%) | 92 (90%) |

| Nonhematological | ||||

| Infections | 17 (17%) | 30 (29%) | 33 (32%) | 34 (33%) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 16 (16%) | 16 (16%) | 16 (16%) | 18 (18%) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 5 (5%) | 5 (5%) | 7 (7%) | 7 (7%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 10 (10%) | 14 (14%) | 15 (15%) | 18 (18%) |

| Dermatological | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 6 (6%) | 10 (10%) |

| . | PAD (n = 102) . | PAD-MEL100-ASCT (n = 102) . | PAD-MEL100-ASCT-LP (n = 102) . | PAD-MEL100-ASCT-LP-L (n = 102) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematological | ||||

| Anemia | 3 (3%) | 16 (16%) | 16 (16%) | 16 (16%) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 17 (17%) | 89 (87%) | 93 (91%) | 93 (91%) |

| Neutropenia | 10 (10%) | 90 (88%) | 91 (89%) | 92 (90%) |

| Nonhematological | ||||

| Infections | 17 (17%) | 30 (29%) | 33 (32%) | 34 (33%) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 16 (16%) | 16 (16%) | 16 (16%) | 18 (18%) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 5 (5%) | 5 (5%) | 7 (7%) | 7 (7%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 10 (10%) | 14 (14%) | 15 (15%) | 18 (18%) |

| Dermatological | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 6 (6%) | 10 (10%) |

During PAD, the most frequent hematologic grade 3-4 toxicities were thrombocytopenia (16%) and neutropenia (10%); non-hematologic grade 3-4 AEs included peripheral neuropathy (16%), pneumonia (10%), fatigue (5%), constipation (5%), and sepsis (3%). Grade 3-4 pneumonia or sepsis was reported in 34% of patients older than 70 years and in 21% of patients younger than that. During Mel100-ASCT, the most frequent AEs were neutropenia (90%), thrombocytopenia (90%), fever of unknown origin (14%), sepsis (8%), and pneumonia (5%). The incidence of infection was 26% in patients older than 70 years and 20% in younger patients.

During LP consolidation, the most frequent AEs were neutropenia (19%), thrombocytopenia (15%), pneumonia (4%), and cutaneous rash (4%). Two patients (3%) developed deep vein thrombosis despite aspirin prophylaxis. Causes of lenalidomide dose-reduction were neutropenia (6%), cutaneous rash (1%), increased creatinine values (1%), peripheral neuropathy (1%), dyspnea (1%), supraventricular tachycardia (1%), and deep vein thrombosis (1%). Causes of lenalidomide discontinuation included thrombocytopenia (4%), neutropenia (3%), and peripheral neuropathy (1%). The median relative dose-intensity of lenalidomide was 100%, and only 8% of patients received less than 75% of the planned dose intensity.

During L maintenance, the most frequent grade 3-4 AEs were neutropenia (23%), thrombocytopenia (3%), pneumonia (5%), and cutaneous rash (6%). The dose of lenalidomide was reduced for neutropenia (3%), thrombocytopenia (2%), and dermatologic AEs (6%). Lenalidomide was discontinued for neutropenia (6%), neutropenia and thrombocytopenia (2%), thrombocytopenia (2%), infections (5%), and cutaneous rash (2%). The median relative dose-intensity of lenalidomide was 100%, and only 15% of patients received less than 75% of the planned dose intensity.

The incidence of second cancers (other than skin cancer) was 0.5% per year of follow-up. We observed 3 cases of second cancers (2 colon cancers, 1 lung neoplasia). Time from MM diagnosis to occurrence of second cancer was 41, 29, and 41 months, respectively. Duration of lenalidomide therapy in the 3 patients who developed second cancers was 13, 24, and 18 months, respectively. In addition, 2 cases of cutaneous basalioma were reported.

Discussion

This is the first study that has evaluated a sequential approach including bortezomib as induction, intermediate-dose melphalan, and ASCT followed by lenalidomide consolidation-maintenance. The immunofixation-negative CR rate was 12% after PAD, 33% after Mel100-ASCT, 49% after LP consolidation, and 54% after L maintenance. After a median follow-up of 66 months, median TTP was 55 months and 5-year OS was 63%. In CR patients, the median TTP was 70 months and the 5-year OS was 83%. The sequential exposure to different drugs and schedules clearly increased the depth of response. The inclusion of maintenance therapy significantly improved outcome and specifically remission duration. Both achievement of CR and continuous therapy have been associated with a positive impact on PFS and OS in young and elderly patients, regardless of treatment administered.10-12,20,21

The increased life expectancy of the general population and the improved performance status of patients older than 65 years should change the treatment paradigm of MM, and more effective intensive approaches may be adopted in the future. Our analyses suggest that efficacy (high CR rate) and treatment feasibility are both essential to improve patient outcome.

The CR rates we reported after induction (12%) and transplantation (33%) are comparable to those observed with the other PAD or VTD regimens in younger patients (postinduction CR rate 7% to 19%; posttransplantation CR rate 21% to 38%).4,22 Bortezomib-based 3-drug induction regimens increased the rate of CR as compared with 2-drug combinations.2,4,22,23 Whether doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, lenalidomide, or thalidomide should be associated with bortezomib plus dexamethasone remains an open question.

In elderly patients, both melphalan-prednisone-thalidomide and melphalan-prednisone-bortezomib induced superior PFS and OS compared with MP and are now considered standards of care.24-26 Conflicting results have been reported with intermediate-dose melphalan and ASCT compared with MP.8,9 In younger patients, higher doses of melphalan proved to be more effective than lower doses.7 In elderly patients, AEs may limit the clinical benefit.8,9 In this study, the rate of toxic deaths was higher in patients older than 70 years; all deaths occurred during the induction and transplantation phase. These data highlight the need for a better patient selection in this approach. Although biological age may differ from chronological age, Mel100 can be considered a valid alternative option for patients up to age 70 years, without comorbidities and with excellent performance status. The ongoing Deutsche Studiengruppe Multiples Myelom XIII trial, comparing tandem melphalan 140 mg/m2 followed by ASCT vs continuous lenalidomide-dexamethasone treatment in patients 60 to 75 years of age, will shed further light on the role of transplantation in elderly patients.27

Consolidation therapy after induction and transplantation improves outcome. CR rate was 33% after Mel100-ASCT and 49% after LP consolidation. In our trial, response upgrade during consolidation and maintenance was mainly noticed in patients who achieved VGPR after transplantation. Similarly, in the randomized phase 3 GIMEMA trial that evaluated VTD consolidation after transplantation, most of the patients who improved to CR after VTD consolidation had achieved at least VGPR after transplantation.22 In another phase 2 trial including patients in VGPR after transplantation, VTD consolidation increased the molecular response rate from 5% to 21%.28 These data show that intensification with bortezomib and/or immunomodulatory drugs improves response rates mainly in patients with sensitive disease who achieved early VGPR. Of note, CR patients enrolled in this trial had a median TTP of almost 6 years and a 5-year OS of 83%. In multivariate analysis, achievement of CR is the strongest factor associated with a significant improvement in PFS and OS, regardless of baseline features. The frequency of molecular response may vary in patients who achieved a CR and more intensive therapy may significantly increase the depth of response. In the near future, more stringent definition of CR is needed to precisely define the frequency of molecular response among patients with immunofixation negative CR. Patients who obtained a molecular CR had a prolonged survival compared with patients who did not, showing that even in responsive patients, the higher the level of response, the longer the survival.28

Limited results were obtained in the exploratory analysis stratified by combining ISS stage and chromosomal abnormalities detected by FISH because of the small sample size. Despite similar survival in the 3 groups, the multivariate analysis showed that ISS stage 1 plus absence of t(4;14) and del17 was associated with a reduced risk of progression and a reduced risk of death. Larger prospective trials are needed to correctly evaluate the impact of the sequential approach in patients with poor prognosis.

In a recent meta-analysis, thalidomide maintenance was consistently associated with a prolonged PFS; an OS benefit was detected in 3 of 6 studies.29 In 2 recent studies including younger patients, PFS was longer in patients who received posttransplantation lenalidomide maintenance compared with those who did not.10,11 Lenalidomide maintenance induced also a significant OS advantage in 1 of the 2 studies.10 In elderly patients, continuous lenalidomide therapy significantly prolonged PFS in comparison with placebo, without survival advantage.12 Bortezomib-thalidomide maintenance after bortezomib-thalidomide-melphalan-prednisone induction significantly prolonged PFS and OS compared with bortezomib-thalidomide-melphalan-prednisone.30 In our study, in which lenalidomide was given until disease progression (median duration of maintenance was 27 months), median TTP was 53 months and 5-years OS was 66%. These data suggest that continuous treatment prolongs duration of remission.

After exposure to continuous therapy, the possible emergence of more resistant clones at the time of relapse may be a concern. Some studies showed shorter survival after progression in patients who received thalidomide maintenance compared with patients who did not.31,32 In this study, median survival after disease progression was 28 months. This figure compares favorably with the survival after disease progression reported in the Velcade as Initial Standard Therapy in Multiple Myeloma trial (28 months after VMP and 27 months after MP) in which no maintenance was used.25 Similar survival time after first relapse was reported in patients who did not receive maintenance enrolled in the non-intensive arm of the Medical Research Council trial (26 months).33 These data suggest that the sequential approach with bortezomib induction, ASCT, and lenalidomide consolidation-maintenance does not induce chemoresistance.

Most AEs occurred during PAD induction and Mel100-ASCT phase. Infections were the most frequent nonhematologic AEs, and caused 6 of 8 deaths related to AEs. Infections and toxic deaths mainly occurred in patients older than 70 years. A careful monitoring and a gentler induction and transplantation strategies are suggested for elderly patients. Antibiotic prophylaxis and the weekly administration of dexamethasone from the first cycle, not adopted in this study, may reduce the incidence of infections during induction. Grade 3 to 4 peripheral sensory neuropathy was observed in 16% of patients. In the bortezomib, melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide trial, the weekly administration of bortezomib significantly reduced the incidence of neuropathy without negatively impacting efficacy.13 These data suggest that bortezomib on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 every 28 days, rather than on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 every 21 days, is the most appropriate schedule for elderly MM patients because it reduces the incidence of peripheral neuropathy without affecting efficacy.

During consolidation and maintenance, the main toxicities were hematological; in particular, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. Both neutropenia and thrombocytopenia did not increase with time and cumulative toxicity was not reported. Median duration of maintenance was 27 months and only 15% of patients received less than 75% of the planned dose intensity. These data demonstrated that lenalidomide is a feasible maintenance option. In our study, patients received lenalidomide 10 mg/day on days 1 to 21 every 28 days; this schedule seems to be less myelotoxic than the alternative schema with lenalidomide daily at 10 or 15 mg/day.10,11 During maintenance, lenalidomide should be re-started when neutrophil count is >1000/mm3, otherwise a delay of up to 2 weeks and eventually dose reduction should be considered to avoid late occurrence of severe neutropenia. In general, maintenance therapy should be adopted if toxicities are equal or inferior to grade 1, to ensure an acceptable quality of life for a long-term therapy.

In conclusion, bortezomib induction followed by Mel100-ASCT and lenalidomide consolidation-maintenance induced a CR rate of 54%, a median TTP of 55 months and a 5-year OS of 63%. This approach may represent an attractive treatment option for elderly patients without comorbidities and with an excellent performance status. Deaths related to AEs were higher in patient ≥70 years suggesting the need of a more careful patient selection.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in the trial, nurses Pusceddu Karin and Garbossa Stefania, data managers Antonella Bono and Antonella Fiorillo, and editorial assistant Giorgio Schirripa.

Authorship

Contribution: M.B. and A.P. conceived and designed the study; F.G., V.M., C.C., N.P., T.G., F.C., S.P., S.F., A.M.L., S.O., F.P., M.O., P.O., V.M., M.T.P., N.G., G.P., and P.C. provided study materials or patients; F.G., V.M., C.C., S.O., F.C., and P.C. collected and assembled data; F.G, V.M., S.O., R.P., and A.P. provided data analysis and interpretation; F.G. and A.P. wrote the manuscript; and all authors provided final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.B. has served as a consultant for and received research funding from Celgene and Janssen-Cilag. A.P. has served as a consultant for and received honoraria from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Millenium, and Onyx. F.G. has received honoraria from Celgene, Janssen-Cilag, and Byotest. F.C. has received honoraria from Celgene and Janssen-Cilag. F.P. has received honoraria from MDS, Celgene, and Janssen-Cilag. M.O. has received honoraria from Celgene, Janssen-Cilag, and Novartis. M.T.P. has received honoraria from Janssen-Cilag. T.G. has received research funding from Celgene. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Antonio Palumbo, Myeloma Unit, Division of Hematology, University of Torino, Via Genova 3, Torino 10126, Italy; e-mail: appalumbo@yahoo.com.