Key Points

Acute GVHD predisposes to autoimmune chronic GVHD, but it is currently unclear how autoimmunity is linked to antecedent alloimmunity.

Loss of central tolerance induction that occurs via functional compromise of thymic epithelial cells may provide such a pathogenic link.

Abstract

Development of acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) predisposes to chronic GVHD with autoimmune manifestations. A characteristic of experimental aGVHD is the de novo generation of autoreactive T cells. Central tolerance is dependent on the intrathymic expression of tissue-restricted peripheral self-antigens (TRA), which is in mature medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTEChigh) partly controlled by the autoimmune regulator (Aire). Because TECs are targets of donor T-cell alloimmunity, we tested whether murine aGVHD interfered with the capacity of recipient Aire+mTEChigh to sustain TRA diversity. We report that aGVHD weakens the platform for central tolerance induction because individual TRAs are purged from the total repertoire secondary to a decline in the Aire+mTEChigh cell pool. Peritransplant administration of an epithelial cytoprotective agent, fibroblast growth factor-7, maintained a stable pool of Aire+mTEChigh, with an improved TRA transcriptome despite aGVHD. Taken together, our data provide a mechanism for how autoimmunity may develop in the context of antecedent alloimmunity.

Introduction

Self-tolerance of the nascent T-cell receptor repertoire is attained through negative selection in the thymus.1 Essential for clonal deletion is the exposure of thymocytes to self-antigens, including those with highly restricted tissue expression. Within the thymus, the ectopic expression of many tissue-restricted peripheral self-antigens (TRAs) is a distinct property of mature medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTEChigh).2,3 TRA expression is controlled partly by the transcription factor autoimmune regulator (Aire).3 Deficits in Aire and/or TRA expression (independent of their causes) impair negative selection and can consequently cause autoimmune disease.2-5

Acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD and cGVHD, respectively) remain the primary complications of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT).6 aGVHD is initiated by alloreactive donor T cells and targets a restricted set of tissues, including the thymus.7,8 The development of human aGVHD predisposes to cGVHD, whose autoimmune manifestations are integral components of disease.9 It remains uncertain, however, whether and how autoimmunity is linked to antecedent alloimmunity. A hallmark of murine aGVHD is the de novo generation of autoreactive T cells from donor HSC10,11 which can mediate the evolution from acute to chronic GVHD.12,13 Because the thymic epithelium is a target of donor T-cell alloimmunity,7,8,14 we hypothesized that thymic aGVHD interferes with the mTEChigh capacity to sustain TRA diversity, thus decreasing the platform for central tolerance. In this context, interventions directed at epithelial cytoprotection are expected to maintain posttransplantation mTEChigh integrity and function. To test these 2 interrelated hypotheses, we used murine allo-HSCT models and investigated the effects of fibroblast growth factor-7 (Fgf7), which boosts thymopoiesis through its mitogenic action on TEC.15,16

Study design

Female C57BL/6 (B6;H-2b), (C57BL/6xDBA/2)F1 (BDF1;H-2bd), Balb/c (H-2d), CBy.PL(B6)-Thy1a/ScrJ (Balb/c-Thy1.1;H-2d), 129/Sv (H-2b), and B6.SJL-PtprcaPep3b/BoyJ (B6.CD45.1;H-2b) mice were kept in accordance with federal regulations. Thymic aGVHD was induced in unirradiated or total body–irradiated recipients14 (supplemental Figure 1). Recombinant human Fgf7 (palifermin, Kepivance, Biovitrum, Sweden) was injected intraperitoneally from day −3 to day +3 after allo-HSCT at a dose of 5 mg/kg per day.15,16

Confocal microscopy of thymic sections was performed using a Zeiss LSM510 (Carl-Zeiss AG, Switzerland).17 The TEC compartment was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSAria, Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). mTEChigh were identified as cells with a CD45-EpCam+Ly51-UEA1+MHCIIhigh phenotype17-19 (supplemental Figure 2). Global gene expression profiling was used to establish TRA diversity in transplant recipients. Microarray data of triplicate samples of pure mTEChigh preparations (Mouse Gene 1.0 ST Array, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA; data available under accession number E-MEXP-3745 at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) were verified by quantitative polymerase chaine reaction. Gene expression data from multiple published sources20,21 and from MOE430 and GNF1M gene atlases (http://biogps.org) were combined for identification of Aire-dependent and Aire-independent TRA (supplemental Methods). Bioinformatics was implemented using software from “The R Project for Statistical Computing” (http://www.r-project.org).

Results and discussion

Total numbers of mTEChigh declined over time in untransplanted adult BDF1 and B6 mice, confirming age-dependent changes of the thymic stroma22 (Figure 1A-B). We then investigated 4 mouse models of age-matched allo-HSCT. In unconditioned recipients of haploidentical HSCT (H-2b→H-2bd; b→bd), the induction of thymic aGVHD14,15 (supplemental Figures 1 and 2) progressively reduced total mTEChigh numbers to ≤103 cells/mouse in animals surviving aGVHD (Figure 1A). This observation was mirrored in allo-HSCT that included total body–irradiated before MHC-identical, MHC-disparate, or haploidentical transplantation (Figure 1B). In these models, the conditioning initially reduced mTEChigh numbers independently of aGVHD, but cell loss was either more pronounced (b→bd) or more protracted (d→b; b→b) in the presence of disease. Hence, reduction in mTEChigh compartment size is a universal manifestation of thymic aGVHD,7 and radiation injury is not mandatory. Contraction of the total mTEChigh pool in unconditioned b→bd recipients corresponded to progressive decreases in the subset that expresses Aire5,23 (Figure 1C-E). In 12-week-old recipients, residual Aire+mTEChigh were low in numbers (<300 cells/thymus) and later became virtually undetectable, owing to the smaller than normal frequencies of Aire-expressing cells among declining mTEChigh numbers.

Acute GVHD impairs mTEChigh compartment size. The mTEChigh compartment was analyzed as a function of recipient age in 4 different murine models of allo-HSCT, as detailed in supplemental Figures 1 and 2. (A) Acute GVHD was induced in 8-week-old unconditioned BDF1 recipients (b→bd, black circles). Untransplanted BDF1 mice (gray squares) or syngeneically transplanted mice (bd→bd, open circles) served as controls. In 1 group, Fgf7 was administered (b→bd + Fgf7, triangles) as described.15 A total of 6 experiments were performed, with 3 to 5 mice per group and experiment. (B) Acute GVHD (TCD+T group, black circles) was induced in irradiated 8-week-old BDF1 recipients (b→bd, left panel), 9-week-old B6 recipients (d→b, middle panel) or 8-week-old B6 recipients (b→b, right panel) as described in supplemental Figures 1 and 2. Untransplanted BDF1 or B6 mice (gray squares) and recipients of TCD bone marrow (TCD group, open circles) were used as controls without disease in all models. A total of 3 experiments were performed. The line graphs show total numbers (mean ± SD) of mTEChigh cells in thymi from individual mice. *P < .05, analysis of variance (ANOVA), aGVHD versus transplanted mice without aGVHD. TCD, T-cell–depleted; n.d., not done. (C-E) Qualitative and quantitative analysis of thymic Aire expression, as described in supplemental Methods. Immunohistochemistry and confocal microscope analysis (C) was performed on thymic frozen sections taken from unconditioned transplant recipients at ages 10, 12, and 15 weeks (ie, 2, 4, and 7 weeks after transplantation; [i-iii] bd→bd, [iv-vi] b→bd, [vii-ix] b→bd + Fgf7). Cytokeratin-18 (CK18, blue) and CK14-positive cells (red) denote cTEC and mTEC, respectively.14,17 Aire+ cells are yellow in color and localize to the thymus medulla. Syngeneically transplanted mice (bd→bd: 18 ± 4 Aire+mTEC/0.04 mm2 medulla) were not different from age-matched untransplanted control mice (data not shown5 ). The flow cytometry plots in (D) depict Aire and MHC class II expression of DAPI–CD45–EpCam+Ly51–UEA1+ mTECs. Numbers represent frequencies (%) of cells (mean ± SD). Total numbers of Aire+mTEChigh in thymi from individual recipient mice (E) was calculated from flow cytometry data (mean ± SD). Groups are the same as in panel (A). A total of 5 experiments were performed, with 3 to 5 mice per group. *P < .05, ANOVA, aGVHD vs transplanted mice without aGVHD.

Acute GVHD impairs mTEChigh compartment size. The mTEChigh compartment was analyzed as a function of recipient age in 4 different murine models of allo-HSCT, as detailed in supplemental Figures 1 and 2. (A) Acute GVHD was induced in 8-week-old unconditioned BDF1 recipients (b→bd, black circles). Untransplanted BDF1 mice (gray squares) or syngeneically transplanted mice (bd→bd, open circles) served as controls. In 1 group, Fgf7 was administered (b→bd + Fgf7, triangles) as described.15 A total of 6 experiments were performed, with 3 to 5 mice per group and experiment. (B) Acute GVHD (TCD+T group, black circles) was induced in irradiated 8-week-old BDF1 recipients (b→bd, left panel), 9-week-old B6 recipients (d→b, middle panel) or 8-week-old B6 recipients (b→b, right panel) as described in supplemental Figures 1 and 2. Untransplanted BDF1 or B6 mice (gray squares) and recipients of TCD bone marrow (TCD group, open circles) were used as controls without disease in all models. A total of 3 experiments were performed. The line graphs show total numbers (mean ± SD) of mTEChigh cells in thymi from individual mice. *P < .05, analysis of variance (ANOVA), aGVHD versus transplanted mice without aGVHD. TCD, T-cell–depleted; n.d., not done. (C-E) Qualitative and quantitative analysis of thymic Aire expression, as described in supplemental Methods. Immunohistochemistry and confocal microscope analysis (C) was performed on thymic frozen sections taken from unconditioned transplant recipients at ages 10, 12, and 15 weeks (ie, 2, 4, and 7 weeks after transplantation; [i-iii] bd→bd, [iv-vi] b→bd, [vii-ix] b→bd + Fgf7). Cytokeratin-18 (CK18, blue) and CK14-positive cells (red) denote cTEC and mTEC, respectively.14,17 Aire+ cells are yellow in color and localize to the thymus medulla. Syngeneically transplanted mice (bd→bd: 18 ± 4 Aire+mTEC/0.04 mm2 medulla) were not different from age-matched untransplanted control mice (data not shown5 ). The flow cytometry plots in (D) depict Aire and MHC class II expression of DAPI–CD45–EpCam+Ly51–UEA1+ mTECs. Numbers represent frequencies (%) of cells (mean ± SD). Total numbers of Aire+mTEChigh in thymi from individual recipient mice (E) was calculated from flow cytometry data (mean ± SD). Groups are the same as in panel (A). A total of 5 experiments were performed, with 3 to 5 mice per group. *P < .05, ANOVA, aGVHD vs transplanted mice without aGVHD.

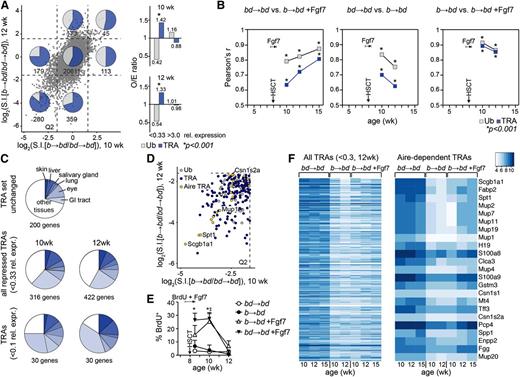

Given the intimate associations among Aire-deficiency, TRA repression, and autoimmunity,3 we determined whether aGVHD interfered with TRA transcription. Development of thymic GVHD (b→bd) altered global gene expression profiles in total residual mTEChigh cell pools isolated at 2 to 4 weeks after transplantation (Figure 2A, supplemental Table 1). Using a special algorithm (supplemental Methods: “Bioinformatics”), we discriminated between TRA and ubiquitously expressed transcripts (Ub) in mTEChigh. Several hundred transcripts were expressed at reduced levels (>3-fold change) in mice with aGVHD (Figure 2A). Notably, the TRA/Ub ratios for repressed transcripts were significantly higher than would have been expected to be observed by chance (O/E ratio >1.0 TRA; <1.0 Ub; P < .001; Figure 2A, right panel)). A low correlation coefficient between TRA expression in b→bd vs bd→bd mice (Pearson’s r = 0.700 and r = 0.625 in 10- and 12-week-old recipients, respectively) indicated a sizable number of TRAs being reduced during lethal aGVHD (Figure 2B, supplemental Figure 3). We interpreted these data such that a contraction in TRA diversity during aGVHD was caused by cellular loss of mTEChigh, in particular Aire-positive mTEC. This explanation was based on the fact that ectopic TRA expression is a stochastic process in which only a limited number of mTEChigh express a given TRA.2,18 A comprehensive coverage of TRA expression is therefore only achieved by a sufficiently large mTEChigh pool, which is, however, missing under conditions of aGVHD. The most substantially reduced TRAs were found to be enriched for genes that are characteristically expressed in tissues known to be targets of cGVHD9 (Figure 2C). Many of these genes belonged to the subset of Aire-dependent TRAs20 (Figure 2D,F, supplemental Figure 3).

Peritransplant administration of Fgf7 sustains a more diverse TRA transcriptome in mTEChigh during aGVHD. Acute GVHD (b→bd) was induced in 8-week-old unconditioned recipient BDF1 mice as in Figure 1A. Global gene expression was analyzed in entire residual mTEChigh cell pools isolated from individual recipients at 10, 12, and 15 weeks of age (ie, 2, 4, and 7 weeks after transplantation). The figure reflects data from 5 independent experiments, with 2 to 4 mice per group and experiment. (A) Left panel: gene expression profiling of mTEChigh in transplant recipients using Mouse Gene 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix). The x- and y-axes represent relative expression of individual genes (given as log2 values of signal intensity ratios, S.I.) in mice with aGVHD (b→bd) vs syngeneically transplanted recipients without disease (bd→bd). Data were plotted as a function of recipient age (10 vs 12 weeks). Genes whose expression levels were enhanced or decreased more than threefold relative to the control group (corresponding to relative expression values given by the S.I. ratios of <0.33 and >3.0, respectively, or <−1.6 and >+1.6 on the log2 scale) were considered to be significantly altered in consequence of aGVHD (threshold is indicated by dashed lines). Q2 is the lower left quadrant, denoting genes whose expression levels were depressed at both 2 and 4 weeks after allo-HSCT (10- and 12-week-old recipients). The inserted numbers denote the absolute numbers of genes in the respective quadrants. Transcripts from a total of 21 759 genes were analyzed. An annotated list of the genes most affected by aGVHD is given in supplemental Table 1. Ub (ubiquitously expressed genes, gray squares) and TRA (dark blue squares). (Right panel) O/E performance analysis (O, observed number of events; E, expected number of events) of the presence of TRA vs Ub among the genes with relative expression <0.33 and >0.3. O/E ratio >1.0 for TRA and <1.0 for Ub; *P < .001 using hypergeometric statistical analysis. A value of O/E = 1.0 represents a distribution among TRA and Ub according to expectations (that is sequestration according to the relative frequencies of TRA and Ub in adult mice without disease). (B) The linear relationship between 2 experimental groups was tested for Ub and TRA using a correlation matrix, as detailed in supplemental Figure 3. The variation of each gene was calculated using the interquartile range, a measure of statistical dispersion. Pearson’s correlation coefficient r is shown as a function of age and time after transplantation. The asterisk (*) symbol indicates a statistical P value for the quality of each measured r at any given time point for TRA and Ub, respectively; *P < .001 of Pearson’s r. (C) Tissue representation of TRA repressed during aGVHD (<0.1 and <0.33 relative expression, respectively, vs mice without GVHD at 10 and 12 weeks of age). As control, a random set of 200 TRAs was used that remained unchanged in the course of GVHD (relative expression ∼1). Many repressed TRAs were specific for tissues of the gastrointestinal tract, skin, and eye. Changes in expression of these genes in response to Fgf7 are given in supplemental Figure 4. (D) Aire dependency of TRA repressed in mTEChigh during aGVHD in 10- and 12-week-old recipients (quadrant Q2; the axes are the same as in panel A). Examples shown are the following: Scgb1a1, secretoglobin; Csn1s2a, casein γ, Mup1, major urinary protein 1; Spt1, salivary protein 1 (see supplemental Table 1). Aire-dependent TRA (yellow circles), Aire-independent TRA (dark blue circles), and Ub (gray circles). (E) Analysis of TEC proliferation in response to Fgf7. Eight-week-old BDF1 mice were left untreated or were treated with Fgf7 from days −3 to +3 after allo-HSCT. All mice simultaneously received 0.8 mg/mL BrdU in their drinking water. mTECs were analyzed for BrdU incorporation at the indicated ages after transplantation. BrdU+ cells (%) ± SD, *P < .001, ANOVA, aGVHD vs mice without aGVHD. (F) Expression levels of individual genes expressed in mTEChigh is given in a heatmap as color-coded log2 value of signal intensities. (Left panel) The map was sorted according to relative expression of genes in mTEChigh (b→bd vs bd→bd mice; 12 weeks old) and contains all TRA with a relative expression of <0.3 during aGVHD in age-matched mice. Enhancement of TRA expression in response to Fgf7 was detectable by higher signal intensities of individual genes. (Right panel) Aire-dependent TRAs were sorted as listed before.

Peritransplant administration of Fgf7 sustains a more diverse TRA transcriptome in mTEChigh during aGVHD. Acute GVHD (b→bd) was induced in 8-week-old unconditioned recipient BDF1 mice as in Figure 1A. Global gene expression was analyzed in entire residual mTEChigh cell pools isolated from individual recipients at 10, 12, and 15 weeks of age (ie, 2, 4, and 7 weeks after transplantation). The figure reflects data from 5 independent experiments, with 2 to 4 mice per group and experiment. (A) Left panel: gene expression profiling of mTEChigh in transplant recipients using Mouse Gene 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix). The x- and y-axes represent relative expression of individual genes (given as log2 values of signal intensity ratios, S.I.) in mice with aGVHD (b→bd) vs syngeneically transplanted recipients without disease (bd→bd). Data were plotted as a function of recipient age (10 vs 12 weeks). Genes whose expression levels were enhanced or decreased more than threefold relative to the control group (corresponding to relative expression values given by the S.I. ratios of <0.33 and >3.0, respectively, or <−1.6 and >+1.6 on the log2 scale) were considered to be significantly altered in consequence of aGVHD (threshold is indicated by dashed lines). Q2 is the lower left quadrant, denoting genes whose expression levels were depressed at both 2 and 4 weeks after allo-HSCT (10- and 12-week-old recipients). The inserted numbers denote the absolute numbers of genes in the respective quadrants. Transcripts from a total of 21 759 genes were analyzed. An annotated list of the genes most affected by aGVHD is given in supplemental Table 1. Ub (ubiquitously expressed genes, gray squares) and TRA (dark blue squares). (Right panel) O/E performance analysis (O, observed number of events; E, expected number of events) of the presence of TRA vs Ub among the genes with relative expression <0.33 and >0.3. O/E ratio >1.0 for TRA and <1.0 for Ub; *P < .001 using hypergeometric statistical analysis. A value of O/E = 1.0 represents a distribution among TRA and Ub according to expectations (that is sequestration according to the relative frequencies of TRA and Ub in adult mice without disease). (B) The linear relationship between 2 experimental groups was tested for Ub and TRA using a correlation matrix, as detailed in supplemental Figure 3. The variation of each gene was calculated using the interquartile range, a measure of statistical dispersion. Pearson’s correlation coefficient r is shown as a function of age and time after transplantation. The asterisk (*) symbol indicates a statistical P value for the quality of each measured r at any given time point for TRA and Ub, respectively; *P < .001 of Pearson’s r. (C) Tissue representation of TRA repressed during aGVHD (<0.1 and <0.33 relative expression, respectively, vs mice without GVHD at 10 and 12 weeks of age). As control, a random set of 200 TRAs was used that remained unchanged in the course of GVHD (relative expression ∼1). Many repressed TRAs were specific for tissues of the gastrointestinal tract, skin, and eye. Changes in expression of these genes in response to Fgf7 are given in supplemental Figure 4. (D) Aire dependency of TRA repressed in mTEChigh during aGVHD in 10- and 12-week-old recipients (quadrant Q2; the axes are the same as in panel A). Examples shown are the following: Scgb1a1, secretoglobin; Csn1s2a, casein γ, Mup1, major urinary protein 1; Spt1, salivary protein 1 (see supplemental Table 1). Aire-dependent TRA (yellow circles), Aire-independent TRA (dark blue circles), and Ub (gray circles). (E) Analysis of TEC proliferation in response to Fgf7. Eight-week-old BDF1 mice were left untreated or were treated with Fgf7 from days −3 to +3 after allo-HSCT. All mice simultaneously received 0.8 mg/mL BrdU in their drinking water. mTECs were analyzed for BrdU incorporation at the indicated ages after transplantation. BrdU+ cells (%) ± SD, *P < .001, ANOVA, aGVHD vs mice without aGVHD. (F) Expression levels of individual genes expressed in mTEChigh is given in a heatmap as color-coded log2 value of signal intensities. (Left panel) The map was sorted according to relative expression of genes in mTEChigh (b→bd vs bd→bd mice; 12 weeks old) and contains all TRA with a relative expression of <0.3 during aGVHD in age-matched mice. Enhancement of TRA expression in response to Fgf7 was detectable by higher signal intensities of individual genes. (Right panel) Aire-dependent TRAs were sorted as listed before.

Because efficient central tolerance requires the full scope of TRA, we next asked whether mTEChigh compartment size and heterogeneity is sustained by using strategies for epithelial cytoprotection. Peritransplant administration of the TEC mitogen Fgf715,16 failed to prevent initial mTEChigh cell loss in b→bd recipients (Figure 1A). However, Fgf7 maintained stable numbers of mTEChigh, including the subset expressing Aire (∼3000 cells/mouse during aGVHD; Figure 1C-E). Consistent with reports that mTEC are continuously replaced in adulthood,18,22 ∼5% of mTECs underwent cell division within 1 week in the b→bd and bd→bd transplant groups (Figure 2E). This frequency increased to ∼15% in mice with aGVHD but that treated with Fgf7. Label retention analyses indicated high turnover of mTEC in response to Fgf7 in b→bd recipients (Figure 2E). Rescue of mTEChigh numbers was therefore the consequence of enhanced proliferation within the entire mTEC compartment. During early aGVHD, the TRA spectrum was not preserved by Fgf7 (Pearson’s r = 0.635 vs bd→bd mice; Figure 2B, supplemental Figure 3). However, a broader array of TRA was expressed by 7 weeks after allo-HSCT as indicated by an expression profile that was closer to that of age-matched bd→bd controls (r = 0.807). Hence, peritransplant administration of Fgf7 sustained a more diverse TRA transcriptome during aGVHD. Individual TRA expression patterns were differentially affected by aGVHD and Fgf7 as some but not all Aire-dependent TRA returned to nearly normal expression in the observation period (Figure 2F, supplemental Figures 3 and 4). However, the molecular mechanism for this biased profile remains to date unknown.

Taken together, our data provide a mechanism for how autoimmunity may develop in the context of aGVHD (supplemental Figure 5). Because thymic-negative selection is sensitive to small changes in TRA expression,4,5 approaches for mTEC cytoprotection may prevent the emergence of thymus-dependent autoreactive T cells12 and thus alter autoimmune outcome. The identification in cGVHD of the yet undefined specificities of autoreactive effector T cells24 will allow to test this argument directly in experimental systems and ultimately in clinical allo-HSCT.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Philippe Demougin (Life Sciences Training Facility, LSTF, Biocenter, University of Basel) for DNA microarray analyses, and Dr Gabor Szinnai (University Children’s Hospital, Basel) for critically reviewing our manuscript.

This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation grants 310030-129838 (W.K.) and 310010-122558 (G.A.H.), and by a grant from the Hematology Research Foundation, Basel, Switzerland (W.K.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.D., G.N., and M.M.H.-H. designed and performed work; R.I. implemented bioinformatics and statistics; and W.K. and G.A.H. share senior authorship and both designed the work and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Werner Krenger, Department of Biomedicine, University of Basel, Mattenstrasse 28, 4058 Basel, Switzerland; e-mail: werner.krenger@unibas.ch.

References

Author notes

G.A.H. and W.K. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 1. Acute GVHD impairs mTEChigh compartment size. The mTEChigh compartment was analyzed as a function of recipient age in 4 different murine models of allo-HSCT, as detailed in supplemental Figures 1 and 2. (A) Acute GVHD was induced in 8-week-old unconditioned BDF1 recipients (b→bd, black circles). Untransplanted BDF1 mice (gray squares) or syngeneically transplanted mice (bd→bd, open circles) served as controls. In 1 group, Fgf7 was administered (b→bd + Fgf7, triangles) as described.15 A total of 6 experiments were performed, with 3 to 5 mice per group and experiment. (B) Acute GVHD (TCD+T group, black circles) was induced in irradiated 8-week-old BDF1 recipients (b→bd, left panel), 9-week-old B6 recipients (d→b, middle panel) or 8-week-old B6 recipients (b→b, right panel) as described in supplemental Figures 1 and 2. Untransplanted BDF1 or B6 mice (gray squares) and recipients of TCD bone marrow (TCD group, open circles) were used as controls without disease in all models. A total of 3 experiments were performed. The line graphs show total numbers (mean ± SD) of mTEChigh cells in thymi from individual mice. *P < .05, analysis of variance (ANOVA), aGVHD versus transplanted mice without aGVHD. TCD, T-cell–depleted; n.d., not done. (C-E) Qualitative and quantitative analysis of thymic Aire expression, as described in supplemental Methods. Immunohistochemistry and confocal microscope analysis (C) was performed on thymic frozen sections taken from unconditioned transplant recipients at ages 10, 12, and 15 weeks (ie, 2, 4, and 7 weeks after transplantation; [i-iii] bd→bd, [iv-vi] b→bd, [vii-ix] b→bd + Fgf7). Cytokeratin-18 (CK18, blue) and CK14-positive cells (red) denote cTEC and mTEC, respectively.14,17 Aire+ cells are yellow in color and localize to the thymus medulla. Syngeneically transplanted mice (bd→bd: 18 ± 4 Aire+mTEC/0.04 mm2 medulla) were not different from age-matched untransplanted control mice (data not shown5). The flow cytometry plots in (D) depict Aire and MHC class II expression of DAPI–CD45–EpCam+Ly51–UEA1+ mTECs. Numbers represent frequencies (%) of cells (mean ± SD). Total numbers of Aire+mTEChigh in thymi from individual recipient mice (E) was calculated from flow cytometry data (mean ± SD). Groups are the same as in panel (A). A total of 5 experiments were performed, with 3 to 5 mice per group. *P < .05, ANOVA, aGVHD vs transplanted mice without aGVHD.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/122/5/10.1182_blood-2012-12-474759/4/m_837f1.jpeg?Expires=1769150801&Signature=yyeFBlss0Z7CeO7Y6TLW5~rItx6fZUpeFpQuWsVMpVqEKm6udl4Wmgt7ll9qg01z1Ai4XaW2EZn8Wm26lRdP01Da9oSN1oq80tGuceMFAoyFcjAmpHkKbGRSN3VvTapk04fRzfYkLozea8ozUziIw-XLTwzCIfEY-pPsiO8kNHWbAZgVmSvCRmU5gQPP9TwtutitS66x9V57D7~YoCPSTWIrRHnELcIJ2JBQMrPZcPAdVkoTwrQc55EF6sWRdD1Nav0TcngBR7KpwpGPILFBdOf427Faj4gI1dxvIvgf5tFz~6xar66-RwC9CqdzDRAEXX~Gp3XXUR0MifhgKSiV2w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal