In this issue of Blood, Pidala et al add a missing piece of information on the impact of amino acid substitutions (AASs) at specific peptide positions of class I antigens.1

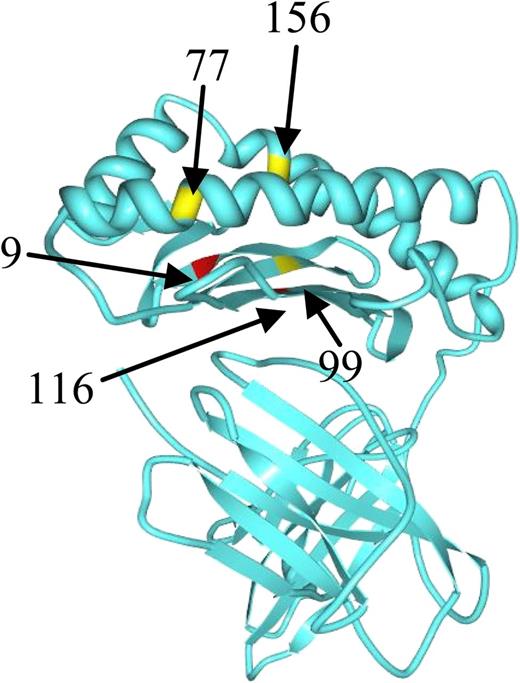

Position of studied amino acid residues with the class I HLA molecule. See the complete Figure 1 in the article by Pidala et al that begins on page 3651.

Position of studied amino acid residues with the class I HLA molecule. See the complete Figure 1 in the article by Pidala et al that begins on page 3651.

Identifying the optimal unrelated donor (UD) for hemopoietic stem cell transplantation has been a moving target over the last few decades.2-6 As shown in the figure, the side view from the paper of Pidala et al shows specific positions of the HLA class I molecule, at which AASs were studied. In multivariate analysis, they find that a mismatch at HLA-C position 116 predicts an increased risk of severe acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD; hazard ratio [HR], 1.45) and mortality (HR, 1.20); a mismatch at HLA-C position 99 is associated with increased transplant-related mortality (TRM; HR, 1.37); and a mismatch at HLA-B position 9 is associated with increased chronic GVHD (HR, 2.28). No substitution at the HLA-A locus is significantly associated with outcome.6 The largest number of patients were in the C116 and C99 mismatched groups.

The issue has been evaluated in the past,4,7 and it is interesting that those reports also were leading in the same direction: some mismatches should be avoided, because they predict GVHD and/or mortality and should be classified as nonpermissive.

There are conceptual and clinical consequences that derive from the findings of Pidala and coworkers.1 Among the first is the biologic and functional role of AASs in key positions of the HLA class I molecule, which had been shown in the past to be crucial for peptide binding and allorecognition8 : the increased risk of severe acute GVHD and/or death, when these mismatches are present, proves the correlation between allorecognition and T-cell activation in vivo. In addition, it is possible that different peptides, or a different peptide presentation, may be driving the acute or chronic variants of GVHD. The increased risk of GVHD was seen in univariate analysis and also after adjusting for patient, disease, and transplant variables including GVHD prophylaxis and T-cell depletion.

The most striking result is that 7/8 allele-matched UD grafts, when the single mismatch lacks AASs at position C116, C99, or B9, have outcomes very similar, if not identical, to 8/8 matched donors: the clinical consequence is obvious. This report expands our ability to select a suitable donor when only 7/8 matched, and this is very important. If one takes substitutions in position C116, the paper tells us that 453 patients (or 7% of the entire population) received a 7/8 mismatched UD graft, lacking the C116 substitution, and their risk of severe acute GVHD was the same as 5274 patients with 8/8 matched donors. The number of UD searches worldwide per year exceeds 40 000 (World Marrow Donor Association report 2011; www.wmda.org): the finding of Pidala and coworkers is thus relevant for >2500 patients/year, finding a 7/8 permissive mismatched donor. The paper also tells us that 9% of the patients had a C116 nonpermissive mismatch; accordingly, >3000 patients/year should decide and/or be counseled of whether to proceed with the transplant, despite a higher risk of complications, or continue the UD donor search to find a better match. This will be based on the clinical conditions of the patient, especially the phase of the disease.

Whatever the decision, we have come a step closer to the definition of a permissive mismatch, and we may now use these definitions to select a 7/8 permissive mismatched UD, with data showing the outcome will be the same as with an 8/8 match. With the large number of UD transplants per year worldwide, it should not be difficult to validate these results prospectively.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal