Abstract

In the present study, we used a knockout murine model to analyze the contribution of the Ca2+-dependent focal adhesion kinase Pyk2 in platelet activation and thrombus formation in vivo. We found that Pyk2-knockout mice had a tail bleeding time that was slightly increased compared with their wild-type littermates. Moreover, in an in vivo model of femoral artery thrombosis, the time to arterial occlusion was significantly prolonged in mice lacking Pyk2. Pyk2-deficient mice were also significantly protected from collagen plus epinephrine-induced pulmonary thromboembolism. Ex vivo aggregation of Pyk2-deficient platelets was normal on stimulation of glycoprotein VI, but was significantly reduced in response to PAR4-activating peptide, low doses of thrombin, or U46619. Defective platelet aggregation was accompanied by impaired inside-out activation of integrin αIIbβ3 and fibrinogen binding. Granule secretion was only slightly reduced in the absence of Pyk2, whereas a marked inhibition of thrombin-induced thromboxane A2 production was observed, which was found to be responsible for the defective aggregation. Moreover, we have demonstrated that Pyk2 is implicated in the signaling pathway for cPLA2 phosphorylation through p38 MAPK. The results of the present study show the importance of the focal adhesion kinase Pyk2 downstream of G-protein–coupled receptors in supporting platelet aggregation and thrombus formation.

Key Points

The tyrosine kinase Pyk2 regulates a p38MAPK-cPLA2 pathway required for thrombin-induced thromboxane A2 production and platelet aggregation.

Pyk2 deletion in mice confers protection against pulmonary thromboembolism and arterial thrombosis.

Introduction

Pyk2, also known as RAFTK or CADβ, is a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase that is highly homologous to the focal adhesion kinase FAK and is predominantly expressed in the CNS and hematopoietic cells.1-3 Like FAK, Pyk2 does not possess SH2 or SH3 domains, but has a centrally located catalytic domain flanked by an N-terminal FERM domain and a C-terminal focal adhesion targeting FAT domain. Pyk2 can be tyrosine phosphorylated and activated by a variety of different cellular stimuli, including cytokines, growth factors, agonists of G-protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs), integrin ligands, and stress stimuli.3-6 Typically, Pyk2 activation is mediated by both Src kinase- and cytosolic Ca2+-dependent pathways. Src kinases phosphorylate Pyk2 at Tyr579, Tyr580, and Tyr881, increasing the catalytic activity of the kinase and promoting autophosphorylation on Tyr402 in the FERM domain.5,6 Even in the absence of Src-mediated phosphorylation, Pyk2 can be activated on increase of the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration.4-7 It has been shown that Ca2+ and calmodulin bind to the N-terminal FERM domain of Pyk2, triggering Pyk2 dimerization, activation, and autophosphorylation at Tyr402.8 Phosphorylated Tyr402 is a binding site for the SH2 domain of Src.5,6 Therefore, Pyk2 is a kinase that can link Ca2+-based signaling pathways to protein tyrosine phosphorylation.

Some observations reported over the past 2 decades have implicated Pyk2 in platelet activation. Pyk2 is highly expressed in megakaryocytes and platelets and is rapidly phosphorylated on stimulation with several platelet agonists, including thrombin, collagen, ADP, estrogens, and VWF.9-13 Phosphorylation of Pyk2 downstream of integrin αIIbβ3 and α2β1 engagement has also been reported.10,14 In thrombin- and VWF-activated platelets, Pyk2 interacts with the actin-based cytoskeleton.9,11 Other studies have documented its association with PI3K, Cas, Shc, and Hic-5.15-18 Thrombin-induced Pyk2 activation was found to be regulated by Ca2+ and protein kinase C, as well as by cytoskeleton reorganization.9,10,18 Because there is such a limited amount of available information, the role of Pyk2 in platelet function remains unknown.

Pyk2-knockout (Pyk2-KO) mice have provided important clues on the function of this kinase in inflammation, atherosclerosis, and angiogenesis. For example, Pyk2 has been demonstrated to play a crucial role in macrophage adhesion and migration by regulating multiple signaling events triggered by chemokine stimulation, including activation of Rho GTPase, phospholipase C, and PI3K.19 Moreover, endothelial cell migration and tube formation promoted by VEGF was found to be strongly impaired in the absence of Pyk2.20 A recent study also showed that Pyk2 is implicated in reactive oxygen species generation and reactive oxygen species–mediated proinflammatory events involved in atherosclerosis.21 These previous observations clearly point to a relevant role for Pyk2 in the cardiovascular system.

In the present study, Pyk2-KO mice were used to unravel the function of this kinase in platelet activation and in vivo thrombus formation. We show that Pyk2 is an important mediator of thrombin-induced platelet aggregation and demonstrate that Pyk2-deficient mice are protected against arterial thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism. These results show an essential role of Pyk2 in the signaling pathways regulating the function of platelets in hemostasis and thrombosis.

Methods

Materials

Thrombin, U46619, and ADP were from Sigma-Aldrich. Convulxin was provided by Dr K. J. Clemetson (Theodor Kocher Institute, University of Berne, Switzerland). AYPGKF was synthesized by PRIMM. Collagen was from Hormon-Chemie. Epinephrine and arachidonic acid were from Mascia Brunelli. FITC-conjugated anti–mouse P-selectin (M130-1) and PE-JON/A (M023-2) were from Emfret Analytics. VX-702 was from Tocris. FITC-labeled fibrinogen was from Molecular Probes. Anti–phospho-cPLA2(Ser505), anti–phospho-ERK1/2(Thr202/Thr204), and anti–phospho-p38 MAPK Abs were from Cell Signaling Technology. The rabbit polyclonal Abs against Pyk2 (N-19), FAK (A17), p38 MAPK (C-20), and ERK (C-14) and the mAb antitubulin (DM1A) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Appropriate peroxidase-conjugated anti-IgG Abs were from Bio-Rad. SB203580 was from Calbiochem. The thromboxane B2 EIA kit was from DRG Diagnostic. Pyk2-KO mice generation was described previously.19 All of the procedures involving the use of C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) and Pyk2-KO mice were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Pavia, by the Committee on Ethics of Animal Experiments of the University of Perugia, and by the Italian Ministry of Public Health (authorization numbers 230/2010-231/2010-B and 232/2010-B).

Preparation of washed mouse platelets

Blood was withdrawn from the abdominal vena cava of anesthetized animals in syringes containing ACD/3.8% sodium citrate (2:1) as anticoagulant. Anticoagulated blood was diluted with HEPES buffer (10mM HEPES, 137mM NaCl, 2.9mM KCl, 12mM NaHCO3, pH 7.4) up to 2 mL and centrifuged for 7 minutes at 180g to obtain platelet-rich-plasma (PRP). PRP was then transferred to new tubes and the remaining RBCs were diluted with HEPES buffer to a final volume of 2 mL and centrifuged again at 180g for 7 minutes. The upper phase was added to the previously collected PRP and 0.02 U/mL apyrase, and 1μM PGE1 were added before centrifugation at 550g for 10 minutes. The supernatant platelet-poor plasma was removed and the platelet pellet was resuspended in 500 μL of HEPES buffer.

Platelet and WBC count in whole blood

Immunoblotting analysis

Platelet samples (0.1 mL, 5 × 108 platelets/mL) were incubated at 37°C and stimulated with different doses of thrombin or treated with an equivalent volume of HEPES buffer for increasing times. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 0.05 mL of SDS-sample buffer 3× (37.5mM Tris, 288mM glycine, pH 8.3, 6% SDS, 1.5% DTT, 30% glycerol, and 0.03% bromophenol blue). Samples were heated at 95°C for 5 minutes and proteins from aliquots of identical volume were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed by immunoblotting with the Abs indicated in the text and in the figure legends at a 1:500 dilution, as described previously.24 Images of reactive bands were acquired using a Chemidoc XRS apparatus (Bio-Rad) and quantification of band intensity was performed using QuantityOne Version 4.6.7 software.

Platelet aggregation

Washed platelets from WT and Pyk2-KO mice (0.25 mL, 3 × 108 platelets/mL) were stimulated under constant stirring with thrombin, AYPGKF, U46619, ADP (in the presence of fibrinogen), or convulxin at the concentrations indicated in the figure in a Chronolog Aggregometer (Mascia Brunelli). Platelet aggregation was monitored continuously over 5 minutes.

Measurement of TxA2 generation

Platelets (0.05 mL, 4 × 108platelets/mL) were stimulated with increasing concentrations of thrombin for 15 minutes at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 2.5mM EDTA and 1mM aspirin. Cells were removed by centrifugation and supernatants were collected and used for the determination of the stable, nonenzymatic hydration product of thromboxane A2 (TxA2), TxB2, with a commercial enzyme immunoassay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Flow cytometry

Samples of washed platelets (106 cells in 0.05 mL of HEPES buffer containing 1mM CaCl2, 1mM MgCl2, and 0.2% BSA), untreated or activated with different doses of thrombin, AYPGKF, or convulxin, were labeled for 10 minutes at room temperature with different specific Abs: PE-conjugated JON/A, FITC-conjugated anti–P-selectin, or FITC-conjugated fibrinogen. Samples were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur instrument equipped with CellQuest Pro Version 4.0.2 software (BD Biosciences). Data analyses were performed using the FlowJo Version 7.6.1 software (TreeStar).

Measurement of [14C]-serotonin secretion

Agonist-induced release of [14C]-serotonin from metabolically labeled platelets was performed as described previously.25

Platelet pulmonary thromboembolism

Collagen plus epinephrine-induced pulmonary thromboembolism was carried out in Pyk2-KO and in WT mice essentially as described previously.26,27 Briefly, mice were challenged with 0.1 mL of a mixture containing 200 μg/mL of collagen and 1.2 μg/mL of epinephrine rapidly injected into one of the tail veins. The mortality of mice in each group was monitored over 15 minutes and data are presented as percentage of animals dead over the total number of animals tested. At the end of each experimental session, surviving animals were killed by an overdose of anesthesia.

Lung histology

Two minutes after the thrombotic challenge, mice were rapidly killed by an overdose of anesthesia and the chest was opened, the trachea was cannulated, and the lungs were perfused with a fixing solution (10% formalin buffered with calcium carbonate). The trachea was then ligated and removed together with the lungs, which were rinsed in cold saline and then fixed in 10% formalin for at least 24 hours. The right-lower lobe was embedded in paraffin and several sections, 5- to 6-μm thick, were cut and stained with H&E to reveal platelet thrombi. The specimens were examined under a light microscope (Axio LAb A.1, Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) by a pathologist unaware of the experimental groups. At least 10 fields, at a magnification of 100×, were observed for every specimen. The total number of identifiable lung vessels per field was counted and the percentage of them occluded by platelet thrombi was annotated.26,27

Femoral artery thrombosis

Photochemical-induced femoral artery thrombosis was induced in anesthetized mice by a method described previously.23,27,28 Briefly, mice were anaesthetized by xylazine (5 mg/kg IP) and ketamine (60 mg/kg IP) and placed on a heated operating table. A 25G needle venous butterfly was inserted in one of the tail veins for the infusion of rose bengal. The left femoral artery was carefully exposed and a laser Doppler probe (Transonic Systems) was positioned onto the branch point of the deep femoral artery distal to the inguinal ligament for monitoring blood flow. The exposed artery was irradiated with green light (wavelength, 540 nm) of a Xenon lamp (L4887; Hamamatsu Photonics) equipped with a heat-absorbing filter via a 3-mm-diameter optic fiber attached to a manipulator. Light irradiation was protracted for 20 minutes; the infusion of rose bengal (20 mg/kg) was started 5 minutes after the beginning of irradiation and lasted for 5 minutes. The end point was set as the cessation of blood flow for > 30 seconds; if no occlusion occurred after 30 minutes, the time was recorded as 30 minutes.

Tail bleeding time

Mice were positioned in a special immobilization cage that keeps the tail of the animal steady and immersed in saline thermostated at 37°C. After 2 minutes, the tip of the tail was transected with a razor blade at 2 mm from its end. The tail was immediately reimmersed in thermostated saline and the time taken to stop bleeding was measured; the end point was the arrest of bleeding lasting for more than 30 seconds. Bleeding was recorded for a maximum of 900 seconds.

Electron microscopy

Resting gel-filtered platelets were fixed for 4 hours at 4°C using cacodylate 0.1N-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 4% wt/vol of glutaraldehyde. The samples were then washed, maintained in cacodylate buffer for a further 4 hours, and then placed in 1% osmium tetroxide and pelleted by centrifugation at 10 000g for 30 seconds. Ultrathin sections of the platelet pellets were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and observed with a Phillips Optic EM208 transmission electron microscope (Philips Electron Optics) at 80 kv.27 For the measurement of platelet size and granule content, micrographs of 50 platelets from WT and Pyk2-KO mice were analyzed from 5 different slides for each strain. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Data and statistical analysis

All of the reported figures are representative of at least 3 different experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism Version 4 software (GraphPad) and the data were compared by unpaired t test.

Results

Mice lacking Pyk2 are protected from thrombosis

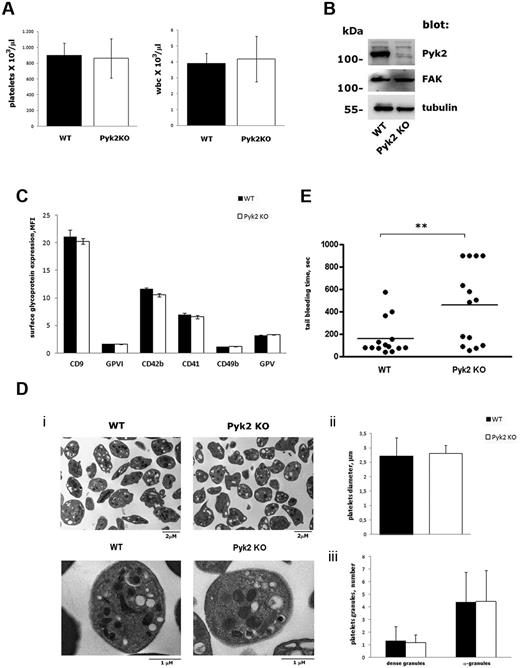

Pyk2-KO mice were viable and fertile and did not manifest any evident bleeding tendency or thrombotic events over their lifespans. No significant differences in the number of circulating platelets or WBCs were observed between WT and Pyk2-KO mice (Figure 1A). Immunoblotting analysis revealed that the absence of Pyk2 in platelets was not compensated for by an altered expression of the related focal adhesion kinase FAK (Figure 1B). No significant differences in the surface expression of some major platelet glycoproteins, including CD9, glycoprotein VI (GPVI), CD42b (GPIbα), CD41 (αIIb subunit), CD49b (α2 subunit), and GPV, were observed between WT and Pyk2-KO mice (Figure 1C). Platelet size and morphology were comparable in WT and Pyk2-KO mice, as revealed by flow cytometry (data not shown) and electron microscopy (Figure 1Di). The average diameter of platelets from Pyk2-deficient mice was very similar to that of platelets from WT mice (WT: 2.55 ± 0.35 μm; Pyk2-KO: 2.61 ± 0.47 μm; Figure 1Dii), and the number of α- and dense granules was comparable in both genotypes (Figure 1Diii). The tail bleeding time was slightly prolonged in Pyk2-KO mice, but only 4 mice of 14 examined had a bleeding time longer than 15 minutes (Figure 1E), indicating that Pyk2 plays a significant but not essential role in primary hemostasis.

Characterization of platelets from Pyk2-KO mice. (A) Platelets and WBC count in whole blood from WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) mice. Results are the means ± SD of determination performed in 10 different mice. (B) Analysis of Pyk2, FAK, and tubulin expression in platelets from WT and Pyk2-KO mice by immunoblotting with specific Abs as indicated on the right. (C) Surface expression of different glycoproteins on WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) mice determined by flow cytometric analysis with specific Abs. Data are expressed as the mean fluorescence intensity ± SD of 3 different experiments performed in duplicate. (D) Electron microscopy analysis of WT and Pyk2-deficient (Pyk2-KO) platelets. Representative images at different magnitudes (7000× and 22 000×, respectively) are reported in panel Di. Measurement of the mean platelet diameter is reported in panel Dii and quantification of α- and dense-granules is shown in panel Diii. Data have been obtained from the analysis of 50 platelets from 5 different slides for each genotype and are expressed as means ± SEM. (E) Tail bleeding time determined in groups of 13 WT and 14 Pyk2-KO mice. Each symbol represents 1 animal. Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference between the 2 groups of animals (P < .01).

Characterization of platelets from Pyk2-KO mice. (A) Platelets and WBC count in whole blood from WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) mice. Results are the means ± SD of determination performed in 10 different mice. (B) Analysis of Pyk2, FAK, and tubulin expression in platelets from WT and Pyk2-KO mice by immunoblotting with specific Abs as indicated on the right. (C) Surface expression of different glycoproteins on WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) mice determined by flow cytometric analysis with specific Abs. Data are expressed as the mean fluorescence intensity ± SD of 3 different experiments performed in duplicate. (D) Electron microscopy analysis of WT and Pyk2-deficient (Pyk2-KO) platelets. Representative images at different magnitudes (7000× and 22 000×, respectively) are reported in panel Di. Measurement of the mean platelet diameter is reported in panel Dii and quantification of α- and dense-granules is shown in panel Diii. Data have been obtained from the analysis of 50 platelets from 5 different slides for each genotype and are expressed as means ± SEM. (E) Tail bleeding time determined in groups of 13 WT and 14 Pyk2-KO mice. Each symbol represents 1 animal. Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference between the 2 groups of animals (P < .01).

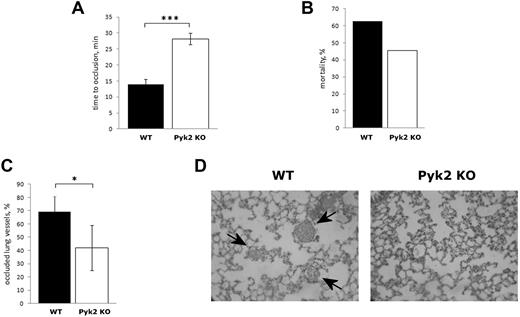

To investigate the possible involvement of Pyk2 in thrombus formation in vivo, we analyzed a model of photochemical-induced femoral artery thrombosis in mice infused with rose bengal. The formation of an occlusive thrombus was monitored by measuring the blood flow on the exposed artery with a laser Doppler probe. In WT mice, blood flow stopped within 15 minutes (14.00 ± 1.58 minutes, n = 5; Figure 2A). In contrast, in Pyk2-KO mice, the time required for artery occlusion was significantly prolonged up to approximately 30 minutes (28.20 ± 1.79, n = 5, P < .001), indicating that Pyk2 plays an important role in arterial thrombosis (Figure 2A).

Analysis of thrombus formation in Pyk2-KO mice. (A) Photochemical-induced arterial thrombosis assesses as time required for occlusion of femoral artery measured by laser Doppler in WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) mice. Data are the means ± SD of measurements performed on 5 animals for both genotypes. ***P < .001. (B) Pulmonary thromboembolism–associated mortality caused by injection of epinephrine plus collagen in WT (black bars, 10 animals analyzed), and Pyk2-KO (white bars, 11 animals analyzed) mice. (C) Percentage of vessels occluded by platelet thrombi in the lungs of WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) mice on injection of collagen and epinephrine as determined by count in 10 microscopic fields for each lung section. Data are reported as the means ± SD. *P < .05. (D) Representative histology images (100×) of lungs from WT and Pyk2-KO mice after collagen plus epinephrine injection. Staining is with H&E. Arrows indicate the platelet-rich thrombi.

Analysis of thrombus formation in Pyk2-KO mice. (A) Photochemical-induced arterial thrombosis assesses as time required for occlusion of femoral artery measured by laser Doppler in WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) mice. Data are the means ± SD of measurements performed on 5 animals for both genotypes. ***P < .001. (B) Pulmonary thromboembolism–associated mortality caused by injection of epinephrine plus collagen in WT (black bars, 10 animals analyzed), and Pyk2-KO (white bars, 11 animals analyzed) mice. (C) Percentage of vessels occluded by platelet thrombi in the lungs of WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) mice on injection of collagen and epinephrine as determined by count in 10 microscopic fields for each lung section. Data are reported as the means ± SD. *P < .05. (D) Representative histology images (100×) of lungs from WT and Pyk2-KO mice after collagen plus epinephrine injection. Staining is with H&E. Arrows indicate the platelet-rich thrombi.

The reduced thrombotic phenotype of Pyk2-KO mice was confirmed in a pulmonary thromboembolism model. On injection of a mixture of collagen plus epinephrine, the mortality of Pyk2-KO mice was lower compared with their WT littermates (Figure 2B). Histologic analysis of slices of isolated lungs collected 2 minutes after the injection of collagen plus epinephrine showed that the percentage of vessels occluded by platelet thrombi was significantly lower in Pyk2-KO than in WT mice (Figure 2C-D). These results indicate that Pyk2 plays a relevant role in thrombus formation in vivo.

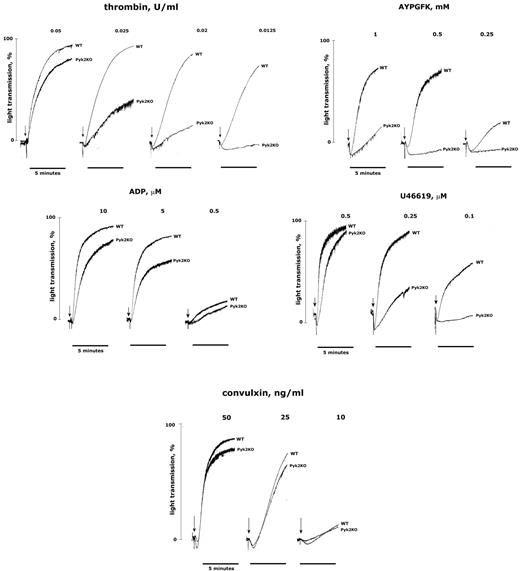

Impaired platelet activation and aggregation in the absence of Pyk2

To characterize the molecular mechanism for the implication of Pyk2 in thrombosis, we analyzed the aggregation of washed platelets from Pyk2-KO mice. Figure 3 shows that aggregation induced by low doses of thrombin was strongly impaired in Pyk2-deficient platelets, but this effect was overcome by increasing the concentration of the agonist. Accordingly, aggregation in response to the weaker but selective PAR4-stimulating peptide AYPGFK was almost completely abolished even when relatively high doses of agonist were used. A defective platelet aggregation in the absence of Pyk2 was also observed on stimulation with low doses of the TxA2 analog U46619 and, to a lesser extent, ADP (Figure 3). In contrast, aggregation triggered by convulxin was not significantly different between WT and Pyk2-deficient platelets (Figure 3) and it was normal on stimulation with collagen or collagen-related peptide (data not shown). These results indicate that Pyk2 may not be essential for GPVI-induced platelet aggregation, but certainly plays a relevant role downstream of GPCRs, including the thrombin receptor PAR4. For this reason, our subsequent investigations were mainly focused on thrombin-stimulated platelets.

Aggregation of Pyk2-deficient platelets. Washed platelets from WT and Pyk2-KO mice were stimulated in an aggregometer with different concentrations of thrombin, AYPGFK, ADP, U46619, or convulxin, as indicated in each panel. For ADP-induced aggregation, 200 μg/mL of fibrinogen was added to the platelet suspension before stimulation with the agonist. Aggregation was monitored as the increase of light transmission up to 5 minutes. Tracings in the figure are representative of at least 3 different experiments.

Aggregation of Pyk2-deficient platelets. Washed platelets from WT and Pyk2-KO mice were stimulated in an aggregometer with different concentrations of thrombin, AYPGFK, ADP, U46619, or convulxin, as indicated in each panel. For ADP-induced aggregation, 200 μg/mL of fibrinogen was added to the platelet suspension before stimulation with the agonist. Aggregation was monitored as the increase of light transmission up to 5 minutes. Tracings in the figure are representative of at least 3 different experiments.

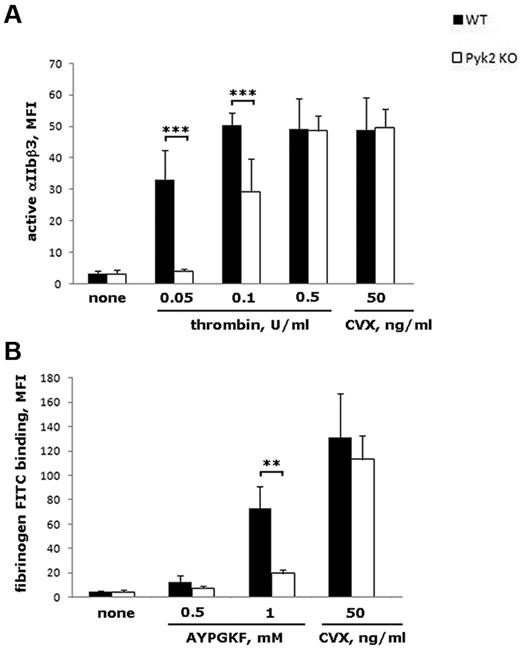

We first analyzed whether the reduced aggregation observed in the absence of Pyk2 was associated with an impaired activation of integrin αIIbβ3 by measuring binding of the conformational-dependent Ab JON/A. Figure 4A shows that JON/A binding to Pyk2-deficient platelets stimulated with 0.05 or 0.1 U/mL of thrombin was strongly reduced compared with platelets from WT mice (by approximately 90% and 40%, respectively). In our experimental conditions, lower doses of thrombin were unable to produce detectable JON/A binding (data not shown), whereas a higher dose of thrombin (0.5 U/mL) caused normal integrin αIIbβ3 activation even in the absence of Pyk2 (Figure 4A). Moreover, platelet stimulation with the GPVI agonist convulxin promoted inside-out activation of integrin αIIbβ3 independently of Pyk2 (Figure 4A). In addition, JON/A binding induced by ADP or U46619, alone or in combination, was not significantly altered in Pyk2-deficient platelets (data not shown). The role of Pyk2 in integrin αIIbβ3 inside-out activation downstream of PAR4, but not of GPVI, was confirmed by measuring the binding of FITC-fibrinogen to AYPGFK- or convulxin-stimulated platelets (Figure 4B).

Analysis of integrin αIIbβ3 inside-out activation. Flow cytometric analysis of PE-JON/A binding (A) or FITC-labeled fibrinogen binding (B) to WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) platelets stimulated with the indicated doses of thrombin, AYPGKF, or convulxin (CVX). Data are expressed as means ± SD of 3-8 different experiments. ***P < .001; **P < .01

Analysis of integrin αIIbβ3 inside-out activation. Flow cytometric analysis of PE-JON/A binding (A) or FITC-labeled fibrinogen binding (B) to WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) platelets stimulated with the indicated doses of thrombin, AYPGKF, or convulxin (CVX). Data are expressed as means ± SD of 3-8 different experiments. ***P < .001; **P < .01

Pyk2 regulates cPLA2 phosphorylation and TxA2 production in thrombin-stimulated platelets

It is known that platelet aggregation by low doses of agonists relies on autocrine stimulation by platelet-released messengers such as ADP or TxA2. Therefore, we compared granule secretion and TxA2 production in WT and Pyk2-deficient platelets stimulated with thrombin. Analysis of P-selectin exposure revealed a modest, albeit statistically significant, reduction of platelet α-granules secretion in the absence of Pyk2, especially at the lowest dose of the agonist analyzed (Figure 5A) that was not observed on stimulation of GPVI (data not shown). Similarly, thrombin-induced release of serotonin from dense granules was only slightly impaired in Pyk2-deficient platelets (Figure 5B). In contrast, measurement of accumulation of the stable metabolite TxB2 in the supernatant of stimulated platelets revealed that thrombin-induced production of TxA2 was dramatically impaired in the absence of Pyk2 (Figure 5C). These results demonstrate that Pyk2 has a minor role in platelet secretion, but is an important regulator of TxA2 synthesis in thrombin-stimulated platelets.

Analysis of platelet secretion and TxA2 production. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of P-selectin exposure in platelets stimulated with the indicated doses of thrombin. Data are expressed as mean fluoresce intensity and are the means ± SD of 4 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .005. Black bars are WT platelets; white bars are Pyk2-deficient platelets. (B) Analysis of thrombin-induced release of [14C]-serotonin from WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) platelets. The release of serotonin in the supernatant of platelets stimulated with the indicated doses of thrombin for 1 minute is expressed as a percentage of the total incorporated radioactivity on subtraction of the values measured in the supernatant of resting platelets. Data are expressed as means ± SD of 3 different experiments. *P < .05; ***P < .005. (C) Accumulation of TxB2 in the supernatant of WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) platelets stimulated with the indicated doses of thrombin for 15 minutes. Data are expressed as means ± SD of 3 different experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01

Analysis of platelet secretion and TxA2 production. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of P-selectin exposure in platelets stimulated with the indicated doses of thrombin. Data are expressed as mean fluoresce intensity and are the means ± SD of 4 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .005. Black bars are WT platelets; white bars are Pyk2-deficient platelets. (B) Analysis of thrombin-induced release of [14C]-serotonin from WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) platelets. The release of serotonin in the supernatant of platelets stimulated with the indicated doses of thrombin for 1 minute is expressed as a percentage of the total incorporated radioactivity on subtraction of the values measured in the supernatant of resting platelets. Data are expressed as means ± SD of 3 different experiments. *P < .05; ***P < .005. (C) Accumulation of TxB2 in the supernatant of WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) platelets stimulated with the indicated doses of thrombin for 15 minutes. Data are expressed as means ± SD of 3 different experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01

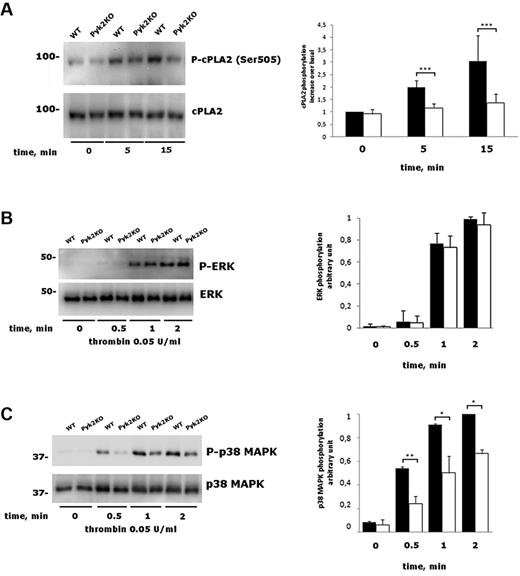

Synthesis of TxA2 is initiated with the release of arachidonic acid by cPLA2, which is activated by intracellular Ca2+ and by phosphorylation on Ser505.29,30 In platelets, cPLA2 phosphorylation is mainly mediated by p38 MAPK.31-34 Figure 6A shows that thrombin-induced cPLA2 phosphorylation on Ser505 was significantly reduced in Pyk2-deficient platelets compared with those from WT littermates. In agreement with previous findings, we confirmed that cPLA2 phosphorylation in thrombin-stimulated platelets was mediated by p38 MAPK, because it was prevented by the specific inhibitor SB203580 (data not shown). In nucleated cells, a functional link between Pyk2 and different MAPKs has been very well documented.7,35-39 Therefore, we analyzed thrombin-induced phosphorylation of both p38 MAPK and ERK1/2. Although the kinetics and extent of ERK1/2 phosphorylation were comparable in WT and Pyk2-deficient platelets, phosphorylation of p38 MAPK was significantly reduced in the absence of Pyk2 at all of the time points analyzed (Figure 6B-C). These results indicate that p38 MAPK links Pyk2 to cPLA2 activation in thrombin-stimulated platelets.

Analysis of cPLA2, ERK, and p38 MAPK phosphorylation. (A) Washed platelets from WT and Pyk2-KO mice were stimulated with 0.05 U/mL of thrombin for 0, 5, or 15 minutes as indicated. The phosphorylation of cPLA2 was evaluated by immunoblotting with a phosphospecific Ab, followed by a subsequent immunoblotting with anti cPLA2, as indicated on the right. Quantification of cPLA2 phosphorylation was performed by densitometric analysis of the immunoblots. Data are reported in the histogram as means ± SD of 4 different experiments. ***P < .001. (B-C) Phosphorylation of ERK (B) and p38 MAPK (C) in platelets from WT and Pyk2-KO mice (Pyk2-KO) stimulated with 0.05 U/mL of thrombin for 0.5, 1, and 2 minutes was analyzed by immunoblotting with phosphospecific Abs as indicated on the right. Blotting with anti-p38 MAPK or anti-ERK was performed as a control for equal loading. Quantitative evaluation of protein phosphorylation is reported in the histograms as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01

Analysis of cPLA2, ERK, and p38 MAPK phosphorylation. (A) Washed platelets from WT and Pyk2-KO mice were stimulated with 0.05 U/mL of thrombin for 0, 5, or 15 minutes as indicated. The phosphorylation of cPLA2 was evaluated by immunoblotting with a phosphospecific Ab, followed by a subsequent immunoblotting with anti cPLA2, as indicated on the right. Quantification of cPLA2 phosphorylation was performed by densitometric analysis of the immunoblots. Data are reported in the histogram as means ± SD of 4 different experiments. ***P < .001. (B-C) Phosphorylation of ERK (B) and p38 MAPK (C) in platelets from WT and Pyk2-KO mice (Pyk2-KO) stimulated with 0.05 U/mL of thrombin for 0.5, 1, and 2 minutes was analyzed by immunoblotting with phosphospecific Abs as indicated on the right. Blotting with anti-p38 MAPK or anti-ERK was performed as a control for equal loading. Quantitative evaluation of protein phosphorylation is reported in the histograms as the means ± SD of 3 different experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01

The defective p38 MAPK-cPLA2 pathway is responsible for the impaired platelet aggregation of Pyk2-deficient platelets

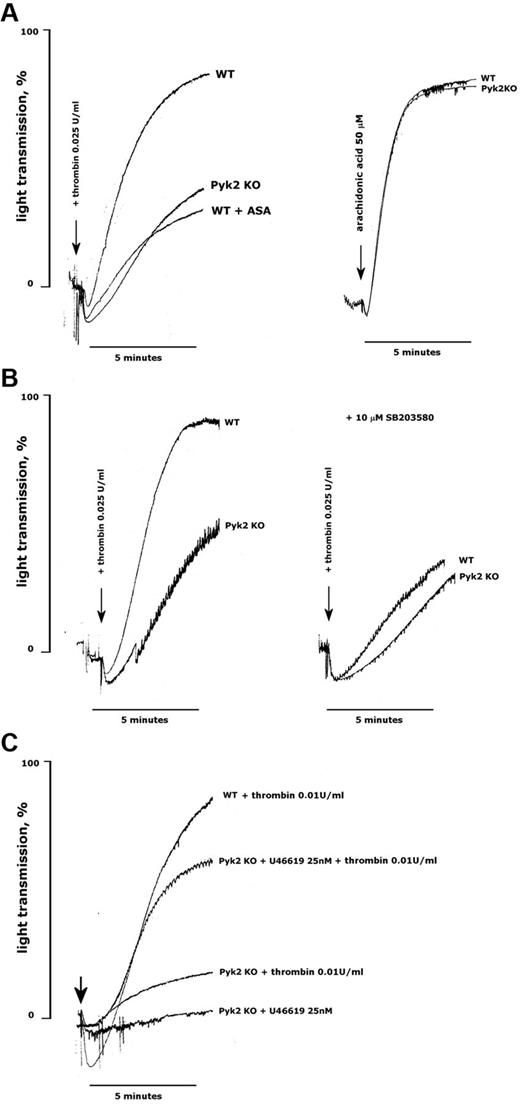

We hypothesized that the reduced production of TxA2 could explain the impaired aggregation of Pyk2-deficient platelets stimulated with thrombin. In support of this possibility, we found that the extent of thrombin-induced aggregation of WT platelets was reduced to a level comparable to that seen in Pyk2-deficient platelets when TxA2 production was blocked by preincubation with aspirin (Figure 7A). However, Pyk2-deficient platelets aggregated normally on direct stimulation with arachidonic acid (Figure 7A). Aggregation of WT platelets with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 was comparable to that of untreated Pyk2-deficient platelets, but SB203580 caused only a minimal and not significant further reduction of aggregation of platelets lacking Pyk2 (Figure 7B). Finally, we observed that the defect of thrombin-induced aggregation caused by the absence of Pyk2 could be significantly, albeit not completely, overcome by the addition of a subthreshold dose of the TxA2 mimetic U46619. Figure 7C shows that 25nM U46619 was unable to trigger aggregation of Pyk2-deficient platelets, but when added together with a low dose of thrombin, it allowed platelets to aggregate to an extent comparable to that induced by thrombin alone on WT platelets.

Reduced TxA2 production is responsible for the defective aggregation of Pyk2-deficient platelets. Aggregation of platelets from WT and Pyk2-KO mice was monitored as an increase of light transmission up to 5 minutes on stimulation with thrombin, arachidonic acid, or U46619, as indicated in each panel. When indicated, platelets were preincubated with aspirin (ASA, 1mM, 30 minutes) or SB203580 (10μM, 10 minutes). Equivalent volumes of DMSO as vehicle were added to control samples. The arrows indicate the addition of the agonists. Traces in the figures are representative of at least 3 different experiments.

Reduced TxA2 production is responsible for the defective aggregation of Pyk2-deficient platelets. Aggregation of platelets from WT and Pyk2-KO mice was monitored as an increase of light transmission up to 5 minutes on stimulation with thrombin, arachidonic acid, or U46619, as indicated in each panel. When indicated, platelets were preincubated with aspirin (ASA, 1mM, 30 minutes) or SB203580 (10μM, 10 minutes). Equivalent volumes of DMSO as vehicle were added to control samples. The arrows indicate the addition of the agonists. Traces in the figures are representative of at least 3 different experiments.

Discussion

In the present study, we used a knockout model to investigate the role of the focal adhesion kinase Pyk2 in platelet function in vivo and ex vivo. Our results show that Pyk2 is an important regulator of platelet aggregation triggered by mild stimulation of GPCRs, including the thrombin receptor PAR4. At the molecular level, our results reveal the involvement of Pyk2 in the signaling pathway for thrombin-induced activation of p38 MAPK and phosphorylation of cPLA2, leading to TxA2 production. Moreover, we have demonstrated that Pyk2 is involved in thrombus formation in vivo.

The activation of Pyk2 in platelets on stimulation by a variety of agonists was reported shortly after the discovery of this kinase almost 15 years ago.9-11 Since then, however, our knowledge on the role of this kinase in platelet function has not advanced significantly, mainly because of the lack of suitable tools and inhibitors. Some peculiar properties of Pyk2, however, suggest that this kinase may represent an important element in many signaling pathways for platelet activation. For example, Pyk2 is unique in that it can be activated by intracellular Ca2+4-8 and therefore may link G-protein–mediated phospholipase C activation and stimulation of protein tyrosine phosphorylation. In this context, we demonstrated herein that Pyk2 is critically involved in platelet activation by thrombin. It was previously shown that thrombin induces a rapid and robust, Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation and activation of Pyk2.9 In the present study, we found that platelets from Pyk2-KO mice show a defective aggregation in response to low, but not high, concentrations of thrombin and to PAR4-activating peptide. This effect was likely the consequence of an impaired integrin αIIbβ3 inside-out activation, because a reduced binding of fibrinogen and of the conformational dependent Ab JON/A was observed in Pyk2-deficient platelets. Although the effect on thrombin-induced aggregation was definitively more pronounced, an impaired aggregation in the absence of Pyk2 was also detected on stimulation with low concentration of other agonists, including ADP and U46619, allowing us to extend the importance of Pyk2 in platelet response to different GPCRs-stimulating agonists. We observed that stimulation of GPVI with collagen, convulxin, or collagen-related peptide caused normal aggregation of Pyk2-deficient platelets, suggesting that this kinase does not play a central role in ITAM-based signaling in platelets. This conclusion is also supported by the observation that inside-out activation of integrin αIIbβ3 in Pyk2-deficient platelets was reduced on stimulation with thrombin, but occurred normally in response to convulxin.

We found that Pyk2 deficiency impaired thrombin-induced secretion of both α-granules and dense granules, but that this effect, albeit statistically significant, was rather modest and therefore is unlikely to contribute to the defective aggregation. In contrast, our results indicate that Pyk2 is a major regulator of TxA2 production in thrombin-stimulated platelets. We propose that the strongly reduced production of TxA2 in Pyk2-deficient platelets is responsible for the defective platelet aggregation in response to thrombin. This conclusion is supported by the evidence that pharmacologic inhibition of TxA2 production in WT platelets reduces the extent of aggregation induced by thrombin to a level comparable to that seen in the absence of Pyk2. Moreover, the defective thrombin-induced aggregation of Pyk2-deficient platelets can be almost completely rescued by the addition of subthreshold amounts of the TxA2 analog U46619.

The production of TxA2 is initiated by the action of cPLA2, which releases arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids. In this study, we report evidence indicating that cPLA2 is actually regulated through Pyk2 in thrombin-stimulated platelets. cPLA2 is typically activated by an increase of intracellular Ca2+ and by phosphorylation on Ser505, which is mediated by different MAPKs.29,30 In platelets, phosphorylation of cPLA2 has been documented to occur in response to several different agonists, including thrombin, and to be mainly mediated by p38 MAPK rather than ERK1/2.31-34 In the present study, we confirmed that thrombin-induced phosphorylation of cPLA2 in mouse platelets is prevented by the specific p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (data not shown) and also documented that cPLA2 phosphorylation is significantly reduced in platelets lacking Pyk2. In addition we found that in thrombin-stimulated platelets, the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, but not ERK1/2, was reduced in the absence of Pyk2. Our results are consistent with many previous studies in different nucleated cells that have consolidated the role of Pyk2 as a major regulator of several MAPKs, including p38 MAPK.7,35-39 Moreover, we found that the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 inhibited thrombin-induced aggregation of WT, but not of Pyk2-deficient platelets. A previous study by Kuliopulos et al reported that a novel, isoform-specific inhibitor of p38 MAKP-α, VX-702, does not prevent platelet aggregation.40 Moreover, considering that VX-702 did not affect collagen-induced aggregation, which is sensitive to aspirin, the role of p38 MAPK in TxA2 generation was questioned.40 We confirmed that, unlike SB203580, VX-702 did not inhibit thrombin-induced aggregation (data not shown). Although SB203580 has been shown to inhibit p38 MAPK in several studies, this observation opens the possibility that, in addition to the p38 MAPK-cPLA2 pathway, Pyk2 deficiency may impair platelet aggregation by targeting additional steps in TxA2 production and action. The observation that in Pyk2-deficient platelets, cPLA2 phosphorylation and TxA2 generation stimulated by thrombin are almost completely prevented, whereas p38 MAPK activation is reduced only by approximately 50%, seems consistent with this possibility. Therefore, although our findings clearly delineate a novel signaling pathway linking Pyk2 to cPLA2 activation in thrombin-stimulated platelets through the regulation of p38 MAPK, additional targets for Pyk2 alone in this pathway may also be involved and remain to be identified.

The reduced ex vivo aggregation of platelets from Pyk2-KO mice in response to low doses of thrombin and to other GPCR agonists suggests that Pyk2, which is currently considered as a promising target in cancer,41 may also represent a novel molecular target for antithrombotic agents. This possibility is strengthened by the findings of the present study demonstrating an important role for Pyk2 in thrombosis in vivo. Using a model of laser-induced arterial thrombosis in Pyk2-KO mice, we have shown a significant contribution of this kinase in vessel occlusion. Moreover, we also found that Pyk2-KO mice were significantly protected against thromboembolism on injection of a mixture of collagen plus epinephrine and a significantly lower number of occlusive platelet thrombi in the lungs were also observed. This model of collagen plus epinephrine-induced platelet pulmonary thromboembolism represents a system in which in vivo platelet activation, in addition to vasoconstriction and/or endothelial damage, plays a central role. This model is sensitive to antiplatelet drugs and in particular to agents that suppress the synthesis or action of TxA2.42-44 The observation that Pyk2-KO mice, in which platelet TxA2 synthesis is impaired, are partially protected from the lethal effects of the injection of collagen plus epinephrine is actually consistent with these previous pharmacologic studies. Moreover, the reduction of the number of histologically detected platelet-rich thromboemboli in lung vessels of Pyk2-deficient mice points to a primary action of Pyk2 in regulating in vivo platelet function. Similarly, the chemical method adopted in this study to trigger arterial thrombosis in mice and based on the intravenous injection of the photoreactive substance rose bengal represents an experimental system known to be sensitive to the pharmacologic inhibition of TxA2.45,46 This model therefore appears to be especially suitable for testing the function of Pyk2, which modulates GPCR-stimulated platelet responses and TxA2 production. Therefore, our results are compatible with a model in which Pyk2 contributes to the activation of platelets with a mechanism that could become crucial in vivo in transforming a normal hemostatic response to a mild vessel wall damage into a thrombotic response.47 In a recent study, we have also found that ex vivo thrombus formation under flow conditions on a collagen matrix was strongly reduced in the absence of Pyk2.14 Our findings also indicate that Pyk2 is relevant, but not essential, for hemostasis because the bleeding time was mildly increased in Pyk2-KO mice. However, we observed a high variability in the time required to stop bleeding in the absence of Pyk2, and a clear bleeding tendency was observed in only approximately one-third of the analyzed mice.

In conclusion, the results of the present study have documented that the Ca2+-dependent focal adhesion kinase Pyk2 plays an important role in platelet activation induced by thrombin and is implicated in thrombus formation in vivo. These observations indicate that Pyk2 may represent a novel target to modulate GPCR-stimulated platelet responses. Moreover, the regulation of mechanisms that contribute to amplifying the platelet response during activation, but do not contribute significantly to the primary response to strong agonists, may represent a way to obtain an antithrombotic effect without significantly impairing hemostasis.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Mario Umberto Mondelli (Department of Infectious Diseases, Fondazione Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy) for collaboration and assistance in the cytofluorimetric analysis.

This work was supported by the Cariplo Foundation (grant 2011-0436), Regione Lombardia and the University of Pavia (project REGLOM16 to I.C.), and the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Perugia (protocols 2010.020.161 and 2009.010.0478). M.F. is supported by the British Heart Foundation (grant PG/06/022/20348).

Authorship

Contribution: I.C., L.C., and A.C. designed and performed the experiments and analyzed the data; S.M. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; G.G. and B.O. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; M.F. contributed vital new reagents, analyzed and interpreted the data, and helped draft the output; M.O. contributed vital new reagents and edited the manuscript; C.B. and P.G. analyzed the data and edited the manuscript; and M.T. designed the research, analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, and guided the overall direction of the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mauro Torti, Department of Biology and Biotechnology, Division of Biochemistry, University of Pavia, via Bassi 21, 27100 Pavia, Italy; e-mail: mtorti@unipv.it.

References

Author notes

I.C. and L.C. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 5. Analysis of platelet secretion and TxA2 production. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of P-selectin exposure in platelets stimulated with the indicated doses of thrombin. Data are expressed as mean fluoresce intensity and are the means ± SD of 4 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .005. Black bars are WT platelets; white bars are Pyk2-deficient platelets. (B) Analysis of thrombin-induced release of [14C]-serotonin from WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) platelets. The release of serotonin in the supernatant of platelets stimulated with the indicated doses of thrombin for 1 minute is expressed as a percentage of the total incorporated radioactivity on subtraction of the values measured in the supernatant of resting platelets. Data are expressed as means ± SD of 3 different experiments. *P < .05; ***P < .005. (C) Accumulation of TxB2 in the supernatant of WT (black bars) and Pyk2-KO (white bars) platelets stimulated with the indicated doses of thrombin for 15 minutes. Data are expressed as means ± SD of 3 different experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/121/4/10.1182_blood-2012-06-438762/4/m_zh89991201190005.jpeg?Expires=1767702639&Signature=Uo6tl1i54Zv8GOYQR5YehaX6cDCdmBEYWbCbqLF2Dhr2MkR2s~4HjzotIkWU9q1fk0v9Qsj9UJMDJH4EQ79LWoOVFqiEQWGyFFFFf8hpxvMchlTyLF9~V6qHab4PPGa1INdm~Wr1Qu45SJ~-063ar7AJEbGyuAVC2L0MVigm4SdZZrZDhY5p92sMd7lAcfUGimJimCqG7OriyTj8j1l~qjQOsFllN1pmf3tXRMIjge2yZ0e6tPegzT0vCB7ux8me2fyJtRNwGmUWRBKalShRG2dHKFID2lmN28oBzOiY9X4e3Umzx8~4dbdLDfHEJkCeEGtwB~IAkfoQbqx~bIjq7Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal