Key Points

In T-LGLL, autologous LGL-depleted PBMCs release high levels of IL-6 contributing to the constitutive STAT3 activation in leukemic LGL.

Leukemic LGLs show SOCS3 down-modulation, which is responsible for lack of the negative feedback mechanism controlling STAT3 activation.

The JAK/STAT pathway is altered in T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia. In all patients, leukemic LGLs display upregulation of phosphorylated STAT3 (P-STAT3) that activates expression of many antiapoptotic genes. To investigate the mechanisms maintaining STAT3 aberrantly phosphorylated using transcriptional protein and functional assays, we analyzed interleukin (IL)-6 and suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 (SOCS3), 2 key factors of the JAK/STAT pathway that induce and inhibit STAT3 activation, respectively. We showed that IL-6 was highly expressed and released by the patients' peripheral blood LGL-depleted population, accounting for a trans-signaling process. By neutralizing IL-6 or its specific receptor with specific antibodies, a significant reduction of P-STAT3 levels and, consequently, LGL survival was demonstrated. In addition, we found that SOCS3 was down-modulated in LGL and unresponsive to IL-6 stimulation. By treating neoplastic LGLs with a demethylating agent, IL-6–mediated SOCS3 expression was restored with consequent P-STAT3 and myeloid cell leukemia-1 down-modulation. Methylation in the SOCS3 promoter was not detectable, suggesting that an epigenetic inhibition mechanism occurs at a different site. Our data indicate that loss of the inhibitor SOCS3 cooperates with IL-6 to maintain JAK/STAT pathway activation, thus contributing to leukemic LGL survival, and suggest a role of demethylating agents in the treatment of this disorder.

Introduction

T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia (T-LGLL) is a heterogeneous disorder characterized by chronic expansion of terminally differentiated cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) bearing a CD3+CD8+CD57+ phenotype.1,2 Although the pathogenesis of T-LGLL is still unknown, the hallmark of the disease rests on the abnormal clonal expansion of antigen-primed mature CTLs that successfully escape activation-induced cell death and remain long-term competence.3 Similar to normal activated CTLs, leukemic T-LGLs exhibit activation of multiple survival-signaling pathways.4,5 Among these, the Janus Kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) intracellular pathway has been associated with LGL transformation. Particularly, it was found that signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) protein, a key component of this signaling, is highly expressed and is constitutively activated in leukemic LGLs compared with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of healthy individuals.4,5

STAT3 is a transcription factor activated by tyrosine phosphorylation in response to growth factors and cytokines,6 preferentially by interleukin (IL)-6. On target cells, IL-6 family members first bind to the IL-6 receptor α (IL-6Rα). The complex of IL-6 and IL-6Rα associates with the signal-transducing membrane protein gp130.7 According to the process termed trans-signaling, also a soluble form of the IL-6Rα (sIL-6Rα) can bind to IL-6 to stimulate cells through gp130.8,-10 After formation of the ligand-receptor complex, the phosphorylated form of STAT3 (P-STAT3) dimerizes and translocates into the nucleus, where it triggers the transcription of target genes controlling a number of important biologic responses. Consistent with this model, Epling-Burnette et al found that in LGLL, STAT3 transcriptionally regulates the expression of myeloid cell leukemia-1 (Mcl-1), suggesting its important role in LGL survival.4 A constitutive activation of STAT3 consequentially promotes cell proliferation as an oncogene.11 Accordingly, STAT3 is persistently phosphorylated in many types of human cancer cell lines, primary tumors,12,-14 and several hematologic malignancies.15,-17

Negative regulation of JAK/STAT pathway activation mainly depends on the suppressor of cytokine-signaling (SOCS) family members.18,19 Among these, the suppressive effect of SOCS3 has been shown to be relatively restricted to STAT3.20 In fact, SOCS3 proteins are synthesized after IL-6 induction via P-STAT3 and are able to inhibit IL-6/STAT3 signaling by binding an integral member of the IL-6 signaling complex, thereby turning it off in a classic feedback loop.21,-23 For its crucial role in regulating STAT3 activation, SOCS3 represents a key protein in lymphocyte homeostasis, the degree of SOCS3 inhibition correlating inversely with the levels of T-cell proliferation.24

The aim of this study was to evaluate the factors responsible for the constitutive activation of STAT3 in LGLL. Using transcriptional and protein assays, we evaluated the expression and function of IL-6, a relevant activating factor inducing STAT3 phosphorylation, which, to our knowledge, has not been previously investigated in this disease. Finally, we evaluated whether STAT3 activation might be linked to the presence of some hot-spot mutations on the SH2 region of STAT3, as reported recently.25,26 These data contribute to define the intrinsic and extrinsic factors leading to the persistent activation of STAT3 in leukemic LGLs and suggest the possible use of demethylating agents for the treatment of this disease.

Materials and methods

Patients and control donors

We studied 27 patients affected by T-LGLL (Table 1). Chronic peripheral blood lymphocytosis (lasting more than 6 months) was sustained by at least 2000 LGLs/μL.27 At the time of the study, no patients had received treatment, with a follow-up ranging from 1 to 16 years (mean, 3 ± 4 years). LGL proliferation ranged from 40% to 90% of the lymphocyte pool and was characterized by a homogeneous pattern of reactivity with the CD3+CD8+CD57+CD56+/−CD16+/− phenotype. In all patients, clonality was demonstrated by molecular analysis of T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement, and often a prevalent expression of a discrete TCR Vβ region was established, according to the methods reported previously.28 A total of 18 healthy donors were used as control participants in all experiments performed, which were approved by the Institutional Review Board. All enrolled patients and control participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Laboratory and clinical features of 27 patients with T-LGLL

| Patient no. . | Sex/Age (y) . | WBC (×109/L) . | ANC (×109/L) . | Hb (g/dL) . | Ly (×109/L) . | LGL (% Ly) . | TCR gene analysis . | Relevant Vβ expression . | Clinical course . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M/48 | 5.9 | 1.1 | 11.3 | 4.8 | 70 | C | 5.1 | Indolent |

| 2 | M/72 | 6.1 | 1.0 | 10.1 | 4.5 | 47 | C | 17 | Indolent |

| 3 | M/58 | 9.3 | 2.2 | 11.5 | 6.5 | 40 | C | 3 | Indolent |

| 4 | F/62 | 9.8 | 2.3 | 12.3 | 6.9 | 61 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 5 | M/65 | 7.8 | 1.5 | 11.2 | 5.7 | 59 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 6 | F/53 | 8.5 | 2.1 | 11.5 | 5.3 | 40 | C | 3 | Indolent |

| 7 | F/58 | 7.4 | 1.8 | 10.9 | 5.1 | 67 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 8 | M/74 | 9.5 | 2.7 | 11.6 | 6.2 | 60 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 9 | M/63 | 9.1 | 1.2 | 10.5 | 7.1 | 75 | C | 13.1 | Indolent |

| 10 | F/53 | 6.7 | 1.1 | 11.2 | 4.7 | 60 | C | 17 | Indolent |

| 11 | F/45 | 8.8 | 1.9 | 11.6 | 6.5 | 55 | C | 4 | Indolent |

| 12 | M/53 | 12.9 | 2.2 | 11.7 | 8.9 | 90 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 13 | F/78 | 10.3 | 1.8 | 10.9 | 7.8 | 65 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 14 | F/50 | 9.6 | 2.1 | 11.7 | 6.9 | 71 | C | 17 | Indolent |

| 15 | F/75 | 9.7 | 1.7 | 12.3 | 7.5 | 79 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 16 | M/65 | 9.8 | 1.5 | 11.6 | 7.5 | 60 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 17 | F/69 | 8.4 | 1.0 | 11.9 | 6.8 | 77 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 18 | F/58 | 7.6 | 1.1 | 11.2 | 5.7 | 51 | C | 14 and 8 | Indolent |

| 19 | M/59 | 8.1 | 2.5 | 12.5 | 5.2 | 57 | C | 20 | Indolent |

| 20 | M/66 | 9.6 | 1.3 | 12.3 | 7.4 | 86 | C | 1 | Indolent |

| 21 | M/66 | 9.3 | 1.9 | 10.6 | 6.5 | 52 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 22 | F/57 | 7.5 | 1.8 | 11.1 | 5.1 | 45 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 23 | F/76 | 9.7 | 0.7 | 11.4 | 8.3 | 80 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 24 | M/54 | 8.6 | 1.1 | 12.5 | 7.1 | 80 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 25 | F/70 | 8.4 | 1.5 | 11.3 | 6.1 | 60 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 26 | M/79 | 9.1 | 1.4 | 12.1 | 7.0 | 74 | C | 17 | Indolent |

| 27 | F/62 | 10.2 | 1.0 | 11.7 | 8.8 | 89 | C | 5.3 | Indolent |

| Patient no. . | Sex/Age (y) . | WBC (×109/L) . | ANC (×109/L) . | Hb (g/dL) . | Ly (×109/L) . | LGL (% Ly) . | TCR gene analysis . | Relevant Vβ expression . | Clinical course . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M/48 | 5.9 | 1.1 | 11.3 | 4.8 | 70 | C | 5.1 | Indolent |

| 2 | M/72 | 6.1 | 1.0 | 10.1 | 4.5 | 47 | C | 17 | Indolent |

| 3 | M/58 | 9.3 | 2.2 | 11.5 | 6.5 | 40 | C | 3 | Indolent |

| 4 | F/62 | 9.8 | 2.3 | 12.3 | 6.9 | 61 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 5 | M/65 | 7.8 | 1.5 | 11.2 | 5.7 | 59 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 6 | F/53 | 8.5 | 2.1 | 11.5 | 5.3 | 40 | C | 3 | Indolent |

| 7 | F/58 | 7.4 | 1.8 | 10.9 | 5.1 | 67 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 8 | M/74 | 9.5 | 2.7 | 11.6 | 6.2 | 60 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 9 | M/63 | 9.1 | 1.2 | 10.5 | 7.1 | 75 | C | 13.1 | Indolent |

| 10 | F/53 | 6.7 | 1.1 | 11.2 | 4.7 | 60 | C | 17 | Indolent |

| 11 | F/45 | 8.8 | 1.9 | 11.6 | 6.5 | 55 | C | 4 | Indolent |

| 12 | M/53 | 12.9 | 2.2 | 11.7 | 8.9 | 90 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 13 | F/78 | 10.3 | 1.8 | 10.9 | 7.8 | 65 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 14 | F/50 | 9.6 | 2.1 | 11.7 | 6.9 | 71 | C | 17 | Indolent |

| 15 | F/75 | 9.7 | 1.7 | 12.3 | 7.5 | 79 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 16 | M/65 | 9.8 | 1.5 | 11.6 | 7.5 | 60 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 17 | F/69 | 8.4 | 1.0 | 11.9 | 6.8 | 77 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 18 | F/58 | 7.6 | 1.1 | 11.2 | 5.7 | 51 | C | 14 and 8 | Indolent |

| 19 | M/59 | 8.1 | 2.5 | 12.5 | 5.2 | 57 | C | 20 | Indolent |

| 20 | M/66 | 9.6 | 1.3 | 12.3 | 7.4 | 86 | C | 1 | Indolent |

| 21 | M/66 | 9.3 | 1.9 | 10.6 | 6.5 | 52 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 22 | F/57 | 7.5 | 1.8 | 11.1 | 5.1 | 45 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 23 | F/76 | 9.7 | 0.7 | 11.4 | 8.3 | 80 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 24 | M/54 | 8.6 | 1.1 | 12.5 | 7.1 | 80 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 25 | F/70 | 8.4 | 1.5 | 11.3 | 6.1 | 60 | C | NF | Indolent |

| 26 | M/79 | 9.1 | 1.4 | 12.1 | 7.0 | 74 | C | 17 | Indolent |

| 27 | F/62 | 10.2 | 1.0 | 11.7 | 8.8 | 89 | C | 5.3 | Indolent |

ANC, absolute neutrophil count; C, clonal rearrangement of TCR genes; F, female; Hb, hemoglobin; LGL, large granular lymphocyte; Ly, lymphocytes; M, male; NF, not found; TCR, T-cell receptor; WBC, white blood cell.

Materials

Fluorescin (FITC)-, phycoerythrin (PE)-, and PeCy5-conjugated monoclonal antibodies used were obtained from Becton Dickinson (Sunnyvale, CA) and included anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD16, anti-CD56, and anti-CD57. Human IL-6, human antibodies anti-IL-6 and anti-IL-6Rα, and mouse IgG1 isotype control were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); the demethylation agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (DAC) from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); and 2-cyano-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-N-(benzyl)-2-propenamide (AG490) from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany).

For western blot analysis, the following primary or secondary antibodies were used: polyclonal anti–Mcl-1, anti-STAT3, and anti-phosphospecific STAT3 at tyrosine 705 antibodies from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA); monoclonal mouse anti-SOCS3 antibody from AbD Serotec (Oxford, UK); monoclonal mouse anti-β-actin antibody from Sigma Aldrich; and horseradish peroxidize-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse immunoglobulins from Amersham Biotechnology (Buckingamshire, United Kingdom).

Flow cytometry analysis

The frequency of LGLs positive for the characteristic antigens was assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis using direct or indirect immunofluorescence assay combining 2 or 3 fluorescences, as described previously.29 Cells were scored using a FACSCalibur analyzer (BD Biosciences) and data processed by the Macintosh CELLQuest software program (Becton Dickinson).

Isolation of LGLs from patients with T-LGLL

PBMCs were obtained by Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma Aldrich) gradient centrifugation. The T-LGLs of patients were obtained using magnetic separations over columns (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) with magnetic MicroBeads coated with anti-human CD57 antibodies (isotype: mouse IgM; Miltenyi Biotec). The putative normal counterpart of pathological LGLs, used as control and represented by CD8+CD57+ cells, were obtained from PBMCs by the FACSAria cell sorter (BD biosciences, San Jose CA). Sorted populations were analyzed for purity and viability (both >95%). We performed preliminary experiments to rule out that cells obtained by FACSAria sorting or by magnetic MicroBeads were functionally different.

RT-PCR expression analysis

Total cellular RNA was extracted from cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol and was treated with DNase (Qiagen). Complementary DNA was generated from 1 μg of total RNA using oligo-dT primer and the AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was carried out in an ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). SYBR Green PCR Master Mix was purchased from Applied Biosystems. The primers used were IL-6: forward 5′-GGCACTGGCAGAAAACAACCTG-3′ reverse 5′-TCACCAGGCAAGTCTCCTCATTGAAT-3′; SOCS3: forward 5′-CAGCTCCAAGAGCGAGTACCA-3′ reverse 5′-AGAAGCCGCTCTCCTGCAG-3′; STAT3: forward 5′-AGGAGGAGGCATTCGGAAA-3′ reverse 5′-AGCGCCTGGGTCAGCTT-3′; IL-6Rα: forward 5′-GGCTGAACGGTCAAAGACATTC-3′ reverse 5′-CGTCGTGGATGACACAGTGA-3′; gp130: forward 5′-GTACATGGTACGAATGGCAGCATAC-3′ reverse 5′-TCCTTGAGCAAACTTTGGGGTAG-3′; glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH): forward 5′-AATGGAAATCCCATCACCATCT-3′ reverse 5′-CGCCCCACTTGATTTTGG-3′. The primers were designed in our laboratory, whereas for STAT3 we used the primers as described by Haider et al.30 Standard curves were generated for each gene. The relative amounts of messenger RNA (mRNA) were normalized for GAPDH expression.

Cell cultures

LGLs purified from patients or CTLs purified from control participants were cultured at 2 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI-1640 medium with 2 mM of l-glutamine and 25 mM of N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (EuroClone, Grand Island, NY); supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; EuroClone), 100 U of penicillin, and 100 μg of streptomycin (EuroClone) per mL; and grown in 5% CO2 at 37°C.

The effect of IL-6 triggering on LGL or CTL culture was studied by incubation with 10 ng/mL of IL-6 to observe STAT3 activation and SOCS3 expression after 1 hour, Mcl-1 expression up to 6 hours, and LGL apoptosis up to 7 days. The same analysis was performed after 96 hours of cell treatment with DAC (5 μM). To inhibit STAT3 phosphorylation, LGLs were cultured with AG490 (50 μM), a specific inhibitor of Jak2. To neutralize IL-6 action, PBMCs were cultured in the presence of a neutralizing antibody to IL-6 or IL-6Rα (2 μg/mL); a mouse IgG1 antibody was used as a control (2 μg/mL).

Measurement of IL-6 and IL-6Rα released

Patient LGLs, autologous LGL-depleted PBMCs, and control CTLs and PBMCs were incubated for 24 hours in RPMI supplemented with 0.5% FCS. Supernatants were collected and centrifuged to remove particulate debris. Levels of IL-6 and sIL-6Rα (secreted form) in the supernatants were determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test kit (R&D Systems). The same test was performed on plasma obtained from the blood of patients and control participants by centrifugation at 4°C, frozen and stored at −80 until use.

Western blot analysis

Cells (5 × 105 for each assay) were lysed with Tris 20 mM, NaCl 150 mM, EDTA 2 mM, EGTA 2 mM, Triton X-100 0.5% supplemented with a complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche; Mannheim, Germany), and sodium orthovanadate 1 mM (Calbiochem). Samples were then subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (acrylamide 10% gels), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, immunostained with the specific antibodies and anti-β-actin monoclonal, and revealed using an enhanced chemiluminescent detection system (Amersham Biosciences). The blots were acquired with the CHEMI DOC XRS supply (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Milan, Italy) and analyzed by Image J launcher software. Quantization on target protein/β-actin, expressed as arbitrary units, was normalized on the Jurkat cell line.

Assays for detection of apoptosis

Apoptosis was assessed by annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) staining (BD Pharmingen). Annexin V/PI staining was performed on PBMCs or LGLs after culture in RPMI 0.5% FCS, with or without the following agents: human recombinant IL-6, DAC, anti-IL6 and anti-IL-6Rα antibodies, and AG490. A staining with anti-CD57-FITC was used to identify leukemic LGLs from PBMCs. In the described experiments, cell death was evaluated by analysis of forward/side scatter fluorescence changes. FACS analysis was performed using a FACS-Calibur Cell Cytometer and the CellQuest software (Becton-Dickinson, Italy).

DNA extraction, modification, and MSP

Genomic DNA was extracted from 5-20 × 106 PBMCs using the Genomic DNA Purification kit (Qiagen). DNA was modified by sodium bisulfite, converting only unmethylated cytosines to uracil, as described by Herman et al.31 Briefly, 2 μg of genomic DNA was denatured with 0.2 mol/L of NaOH at 37°C for 10 minutes and treated with 10 mmol/L of hydroquinone and 3M of sodium bisulfite (pH 5.0) at 50°C for 16 hours. The bisulfite-modified DNA samples (2-μL aliquots) were used as a template for methylation-specific PCR (MSP) as described,32 using either a methylation-specific or unmethylation-specific primer set. The sequence amplified was from nucleotides –525 to –384 of the SOCS3 promoter region, defining the start codon ATG is as +1. Methylation-specific primers were forward: 5′-GGAGATTTTAGGTTTTCGGAATATTTC-3′ and reverse: 5′-CCCCCGAAACTACCTAAACGCCG-3′,33 whereas unmethylation-specific primers were forward: 5′-GTTGGAGATTTTAGGTTTTTGGAATATTTT-3′ and reverse: 5′-AAACCCCCAAAACTACCTAAACACCA-3′. PCR products were analyzed in 2% agarose gel stained with Syber Safe (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and were visualized under UV illumination.

Bisulfite sequencing

Bisulfite-modified DNA was amplified using primers recognizing the SOCS3 promoter region from nucleotides –704 to –186 (forward: 5′-GATTTGAGGGGGTTTAGTTTTAAGGA-3′ and reverse: 5′-CCACTACCCCAAAAACCCTCTCCTAA-3′) as reported by Isomoto et al.33 The PCR products were cloned into the PCR II vector in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions using the TOPO-TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNA purified from 5 randomly picked clones using the plasmid miniprep kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) were obtained and prepared for automated DNA sequencing analysis. The reaction conditions were as follows: 96°C for 10 seconds, 50°C for 5 seconds, and 60°C for 4 minutes for 25 cycles. DNA was sequenced using dye terminator technology and an ABI 3130 sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Screening of SOCS3 and STAT3 mutations

To sequence the SOCS3 gene, we used primers designed to cover the entire coding region (678 bp), the upstream primer 5′-CATGCCCTTTGCGCCCTT, and the downstream primer 5′-AGATCCACGCTGGCTCCGT, as reported by Cho-Vega et al.34 For the screening of STAT3 mutations D661V, D661Y, D661H, Y640F, N647I, and K658N, recently described by Koskela et al,25 we constructed the same set of primers25 to amplify the exon 21, where all of the mutations are located, and we analyzed the DNA of purified LGLs and of the remaining autologous PBMCs. As healthy controls, we used DNA both from CD8+CD57+ cells and PBMCs of buffy coats. DNA was sequenced as described in the previous paragraph.

The presence of D661Y and Y640F mutations nondetectable by direct sequencing, because of the low sensitivity of the method (reaching 25% of positive cells; supplemental Figure) was also analyzed by a DNA tetra-primer amplification refractory mutation system assay, as reported by Jerez et al.26

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean plus or minus the standard error (SE), and statistical analysis was performed by the Student t test. A value of P < .05 was accepted as significant.

Results

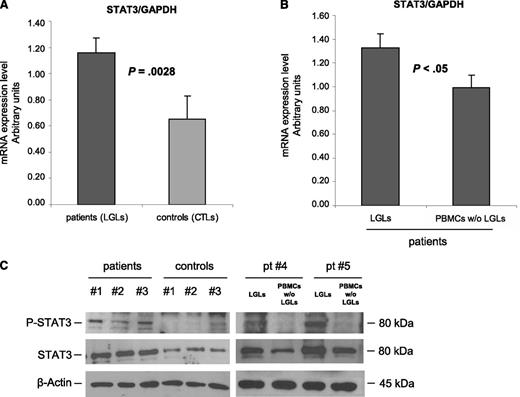

Leukemic LGLs display high expression and activation of STAT3

According to previously published data,4 RT-PCR results showed that STAT3 is overexpressed in purified leukemic T-LGLs compared with normal CTLs (mRNA arbitrary units: 1.16 ± 0.12 and 0.65 ± 0.18, respectively; P = .0028) (Figure 1A). Moreover, by purifying specific LGL subsets, we observed that the highest expression of STAT3 was specifically detected on CD3+CD57+ clonal LGLs, whereas autologous LGL-depleted PBMCs were consistently shown to display significantly lower amounts of STAT3, both by RT-PCR and by western blot analysis (Figure 1B, mRNA arbitrary units: 1.33 ± 0.11 and 0.99 ± 0.10, respectively; n = 10; P < .05; Figure 1C, densitometry: 1.14 ± 0.12 in patients and 0.45 ± 0.10 in control participants; P = .014). Moreover, because STAT3 phosphorylation in tyrosine residue confers the ability of STAT3 to induce transcription of several antiapoptotic genes, we analyzed the tyrosine-phosphorylation status of STAT3 in patients’ LGLs compared with control participants. We observed that leukemic LGLs showed increased, although variable, amounts of activated STAT3, which were very low or even absent in control participants (Figure 1C).

STAT3 expression analysis. (A-B) STAT3 mRNA expression average (± SE) obtained by RT-PCR and normalized on GAPDH. Panel A reports results from patients’ LGLs (n = 27) compared with control participants’ CTL cells (n = 18). Panel B represents patients’ LGLs compared with autologous PBMCs depleted of LGLs (n = 10). The average differences were statistically significant (P = .0028 and P < .05, respectively). (C) Evaluation of P-STAT3 and total STAT3 by western blot analysis. β-Actin served as a loading control. Representative cases for patients’ LGLs, control participants’ CTLs, and autologous LGL-depleted PBMCs (patients #4 and #5) are reported.

STAT3 expression analysis. (A-B) STAT3 mRNA expression average (± SE) obtained by RT-PCR and normalized on GAPDH. Panel A reports results from patients’ LGLs (n = 27) compared with control participants’ CTL cells (n = 18). Panel B represents patients’ LGLs compared with autologous PBMCs depleted of LGLs (n = 10). The average differences were statistically significant (P = .0028 and P < .05, respectively). (C) Evaluation of P-STAT3 and total STAT3 by western blot analysis. β-Actin served as a loading control. Representative cases for patients’ LGLs, control participants’ CTLs, and autologous LGL-depleted PBMCs (patients #4 and #5) are reported.

STAT3 mutations in LGLs

We analyzed whether LGLs in the patients showed any of the hot-spot mutations on the SH2 portion of STAT3, as demonstrated by Koskela et al25 in a recent study where they correlated these mutations with STAT3 activation. We performed sequencing of exon 21 of chromosome 17 where the SH2 domain of STAT3 is located on DNA purified from LGLs (CD57+), from the remaining autologous PBMCs (CD57−), and from the PBMCs and CTLs of control participants. By sequencing, we found the presence of the STAT3 mutation (Y640F position) in only 1 patient (patient #24; supplemental Methods). By amplification refractory mutation system PCR for the Y640F and D661Y STAT3 mutations, accounting for the most frequent mutations reported25,26 with a sensitivity of less than 10% of clones, we found 5 additional mutated cases (patients #9, #20, and #23 for Y640F and patients #12 and #27 for D661Y). Taken together, STAT3 mutations were detected in 6 (22.2%) of 27 patients. Mutations were detected only in purified LGLs. The percentage of mutations found contrasts with STAT3 upregulation, which was shown in all patients analyzed.

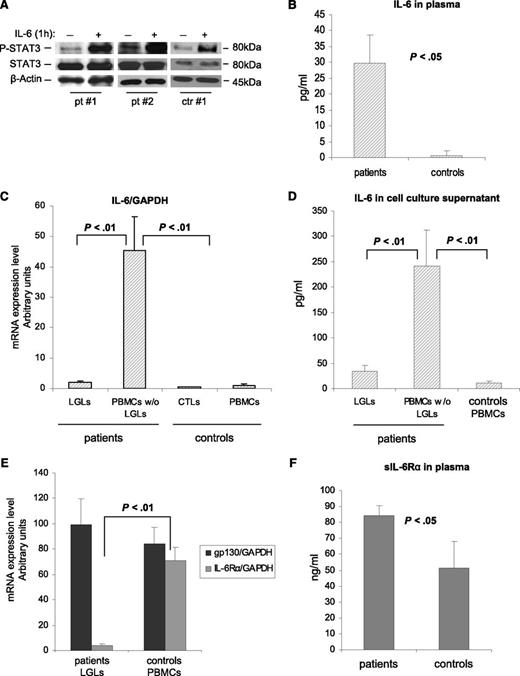

Mononuclear cells of patients produced IL-6 and the soluble form of IL-6Rα

The role of IL-6 in STAT3 upregulation is well known.6 To evaluate the effects of IL-6 on STAT3 activation in leukemic LGLs, we added exogenous IL-6 to purified LGL cultures. We observed that after 1 hour of IL-6 stimulation, P-STAT3 increased both in control participants and in patients, indicating that also in leukemic LGLs, STAT3 is responsive to IL-6 as in physiologic conditions (Figure 2A). Interestingly, on the ELISA test we observed higher levels of IL-6 in the plasma of patients vs that of control participants (Figure 2B; 29.67 ± 8.91 pg/mL and 0.67 ± 1.37 pg/mL, respectively; P < .05). Furthermore, we observed that cells in the patients expressed higher mRNA levels of IL-6 compared with those in the control participants. This increased expression of IL-6 mRNA was restricted to the LGL-depleted PBMC population (Figure 2C; P < .01). Consistent results were obtained by the ELISA test, analyzing IL-6 levels in the supernatants of cell culture after 24 hours of incubation. Patients’ PBMCs depleted of LGLs released high levels of IL-6 compared with autologous purified leukemic LGLs and control PBMCs (Figure 2D; P < .01). Then, we analyzed mRNA expression of the IL-6R system that is composed of 2 functionally different chains: a ligand-binding chain, known as IL-6Rα, and a non–ligand-binding but signal-transducing chain, gpl30. By RT-PCR, we found that IL-6Rα was poorly expressed by the LGLs in the patients compared with the PBMCs in the control participants (mRNA arbitrary units: 3.76 ± 1.44 and 70.86 ± 10.85, respectively; P < .01), whereas gp130 was not differently expressed in the 2 groups (Figure 2E). By the ELISA test, we showed that the loss of IL-6Rα by leukemic LGLs is balanced by a significantly higher level of IL-6Rα in a soluble form in the plasma of patients compared with control participants (Figure 2F; 84.32 ± 6.38 ng/mL and 51.22 ± 16.65 ng/mL, respectively; P < .05). These results suggested that a relevant process of trans-signaling mediating IL-6 activation takes place in LGLL.

IL-6 effect on P-STAT3 and expression and release of IL-6 and its receptors. (A) Evaluation by western blot analysis of P-STAT3 and STAT3 in cell extracts after 1 hour of incubation with or without IL-6 at 10 ng/mL. β-Actin served as a loading control. P-STAT3 increases with IL-6 both in patients and in control participants. (B) Histograms of IL-6 levels in the plasma of patients and control participants measured by the ELISA test. (C) IL-6 mRNA expression and (D) secretion levels in patients (LGLs and LGL-depleted PBMCs, n = 27) and in control participants (CTLs and PBMCs, n = 18). (E) Histograms of IL-6Rα and gp130 mRNA expression levels in patients (LGLs) and in control participants (PBMCs). (F) Histograms of the secreted form of IL-6Rα in plasma measured by the ELISA test. All results are expressed as mean ± SE.

IL-6 effect on P-STAT3 and expression and release of IL-6 and its receptors. (A) Evaluation by western blot analysis of P-STAT3 and STAT3 in cell extracts after 1 hour of incubation with or without IL-6 at 10 ng/mL. β-Actin served as a loading control. P-STAT3 increases with IL-6 both in patients and in control participants. (B) Histograms of IL-6 levels in the plasma of patients and control participants measured by the ELISA test. (C) IL-6 mRNA expression and (D) secretion levels in patients (LGLs and LGL-depleted PBMCs, n = 27) and in control participants (CTLs and PBMCs, n = 18). (E) Histograms of IL-6Rα and gp130 mRNA expression levels in patients (LGLs) and in control participants (PBMCs). (F) Histograms of the secreted form of IL-6Rα in plasma measured by the ELISA test. All results are expressed as mean ± SE.

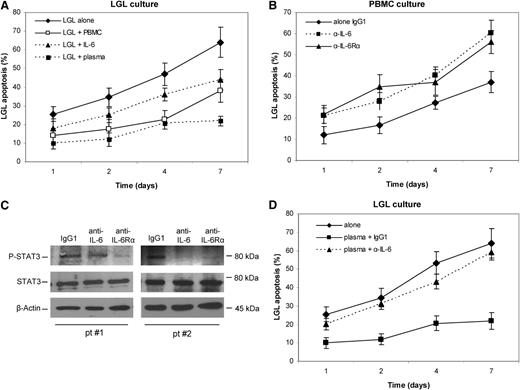

IL-6 is involved in survival cell maintenance and in STAT3 phosphorylation status

As reported in Figure 3A, freshly purified LGLs demonstrated better survival when in culture with the residual autologous PBMCs or alone in the presence of exogen IL-6 stimulation or with autologous plasma (10%). To evaluate whether LGL survival and STAT3 phosphorylation are dependent on IL-6 released by PBMCs in patients, such PBMCs were incubated in the presence of blocking antibodies to IL-6 or IL-6Rα and both P-STAT3 and apoptosis levels after 1, 2, 4, and 7 days of culture were analyzed. Our results indicated that LGL apoptosis statistically increased (Figure 3B) with a concomitant decrease in P-STAT3 (Figure 3C) after incubation with anti-IL-6 or anti-IL-6Rα. Moreover, we observed that the survival rescue obtained in LGL culture with autologous plasma is abrogated with the addition of the neutralizing antibodies, thus confirming that autologous plasma IL-6 mediates LGL survival (Figure 3D). These results suggest that IL-6 is necessary to maintain STAT3 activation, thereby supporting survival of leukemic LGLs.

Evaluation of LGL apoptosis and P-STAT3 level in the presence of neutralizing antibodies against IL-6 and IL-6Rα. Apoptosis was measured after 1, 2, 4, and 7 days of culture in RPMI 0.5% FCS by Annexin V/PI. Staining with anti-CD57-FITC was used to identify leukemic LGLs from PBMCs. (A) Purified LGL apoptosis was analyzed in cells cultured alone or cells cultured with autologous PBMCs, IL-6, or autologous plasma 10%. (B) LGL apoptosis time course and (C) western blot analysis of P-STAT3 and STAT3 in PBMC at 4 hours of culture (2 representative patients) with control IgG1, anti-IL6, and anti-IL-6Rα antibodies. β-Actin served as a loading control. (D) LGL apoptosis in culture alone and with autologous plasma in the presence of an isotype control antibody, anti-IL6 antibody, and anti-IL-6Rα antibody. The apoptosis histograms show the mean results (± SE) from 4 individual experiments.

Evaluation of LGL apoptosis and P-STAT3 level in the presence of neutralizing antibodies against IL-6 and IL-6Rα. Apoptosis was measured after 1, 2, 4, and 7 days of culture in RPMI 0.5% FCS by Annexin V/PI. Staining with anti-CD57-FITC was used to identify leukemic LGLs from PBMCs. (A) Purified LGL apoptosis was analyzed in cells cultured alone or cells cultured with autologous PBMCs, IL-6, or autologous plasma 10%. (B) LGL apoptosis time course and (C) western blot analysis of P-STAT3 and STAT3 in PBMC at 4 hours of culture (2 representative patients) with control IgG1, anti-IL6, and anti-IL-6Rα antibodies. β-Actin served as a loading control. (D) LGL apoptosis in culture alone and with autologous plasma in the presence of an isotype control antibody, anti-IL6 antibody, and anti-IL-6Rα antibody. The apoptosis histograms show the mean results (± SE) from 4 individual experiments.

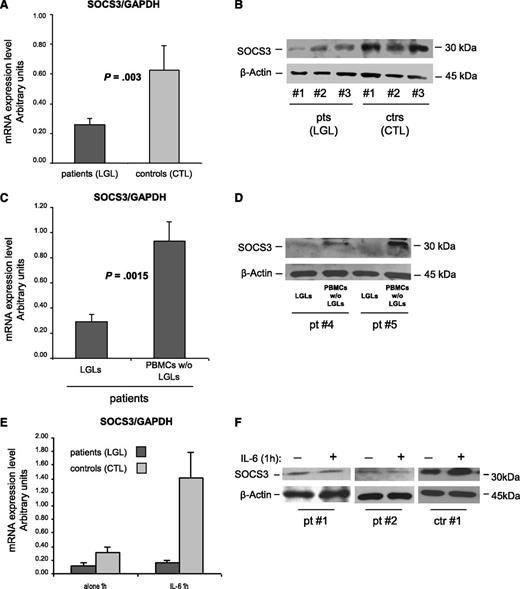

SOCS3 is down-expressed in pathological LGLs

To obtain insight into the mechanism sustaining abnormal STAT3 activation, in patients’ LGLs using RT-PCR and western blot, we analyzed the levels of SOCS3, the physiological inhibitor of STAT3 signaling. Because SOCS3 transcription is induced by IL-6 through P-STAT3 and high levels of P-STAT3 and IL-6 were demonstrated in these leukemic cells, we expected to detect high amounts of SOCS3. Surprisingly, we observed that the amounts of SOCS3 mRNA and protein were significantly lower in patients compared with control participants (Figure 4A; mRNA arbitrary units: 0.26 ± 0.04 in patients and 0.63 ± 0.17 in control participants; P = .003; Figure 4B; western blot: 0.59 ± 0.05 in patients and 0.85 ± 0.10 in control participants; P = .014). In 10 patients, we then evaluated SOCS3 mRNA and protein in LGLs and in the autologous LGL-depleted PBMCs. The results indicated that SOCS3 was specifically down-modulated in LGLs, whereas the remaining cells of patients showed results that are consistent with those of control CTLs (Figure 4C-D; P = .0015).

SOCS3 expression analysis. (A-D) SOCS3 expression average (± SE) obtained by RT-PCR and normalized on GAPDH and western blot analysis of cell extracts for SOCS3 in 3 representative patients (LGLs) and 3 control participants (CTLs). β-Actin served as a loading control. Panel A and B report results from patients’ LGLs (n = 27) compared with control participants’ CTLs (n = 18). Panel C and D report data from patients’ LGLs compared with autologous LGL-depleted PBMCs. The differences were statistically significant (panel A, P = .003 and panel C, P = .0015). (E) Mean results (± SE) of SOCS3 mRNA expression and (F) protein level in 2 representative patients and 1 control participant obtained by cells after culture in medium alone or medium with IL-6 for 1 hour.

SOCS3 expression analysis. (A-D) SOCS3 expression average (± SE) obtained by RT-PCR and normalized on GAPDH and western blot analysis of cell extracts for SOCS3 in 3 representative patients (LGLs) and 3 control participants (CTLs). β-Actin served as a loading control. Panel A and B report results from patients’ LGLs (n = 27) compared with control participants’ CTLs (n = 18). Panel C and D report data from patients’ LGLs compared with autologous LGL-depleted PBMCs. The differences were statistically significant (panel A, P = .003 and panel C, P = .0015). (E) Mean results (± SE) of SOCS3 mRNA expression and (F) protein level in 2 representative patients and 1 control participant obtained by cells after culture in medium alone or medium with IL-6 for 1 hour.

To determine whether the SOCS3 gene mutation was present, the SOCS3 coding region was sequenced, and neither mutation nor alternative splicing of the SOCS3 gene was detected in any of the 27 patients studied.

SOCS3 is unresponsive to IL-6 triggering in pathological LGLs

Provided with the evidence of a high amount of P-STAT3 in the LGLs of patients, the above results suggest that SOCS3 might be unresponsive to P-STAT3 activation in patients with T-LGLL, thus leading to abnormal function of the STAT3/SOCS3 axis. To address this issue, we stimulated in vitro patients’ LGLs or control participants’ CTLs with IL-6 to induce SOCS3 expression through P-STAT3. By western blot and RT-PCR analyses, strikingly different effects on SOCS3 after STAT3 phosphorylation were observed in the 2 study groups. After IL-6 activation, SOCS3 expression became markedly increased only in healthy individuals, whereas in patients’ LGLs, it remained quantitatively unchanged at nearly undetectable levels (Figure 4E-F). These results indicate an aberrant behavior of STAT3/SOCS3 signaling in patients’ LGLs, STAT3 being physiologically able to respond to the IL-6 trigger, whereas SOCS3 does not.

The demethylating agent DAC restores IL-6–mediated SOCS3 expression in patients' LGLs

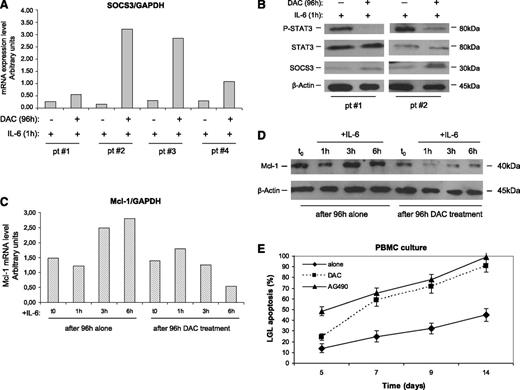

In several tumors where the JAK/STAT pathway is involved, SOCS3 was occasionally found silenced through an epigenetic mechanism.32,33,35,36 To evaluate whether an epigenetic mechanism accounts for SOCS3 inhibition, leukemic LGLs were incubated with DAC. After 96 hours of incubation with this agent, IL-6–treated LGLs showed an increase of SOCS3 expression both at the transcription and protein levels (Figure 5A-B), progressively fading in the next hours (data not shown) because SOCS3 is short-living. On the contrary, LGLs not treated with DAC maintained that SOCS3 down-modulated independently from IL-6 stimulation.

Effect of DAC and IL-6 treatment on SOCS3, STAT3, P-STAT3, and Mcl-1 expression and apoptosis of leukemic LGLs. Results were obtained by LGL cultures treated for 96 hours with or without DAC and then stimulated with IL-6 for 1 hour. (A) SOCS3 expression levels in LGLs obtained by RT-PCR and normalized on GAPDH. The results of 4 representative patients are reported. (B) Western blot analysis of LGL extracts for P-STAT3, total STAT3, and SOCS3. β-Actin served as a loading control. Two representative cases of patients are shown. (C) Mcl-1 expression levels obtained by western blot analysis (D) and by RT-PCR of LGLs from a representative patient with LGLL. (E) Annexin V/PI assay measuring LGL mortality percentage (± SE) in PBMC culture after DAC treatment (4 days of incubation) or with AG490, inhibiting STAT3 signaling. A staining with anti-CD57-FITC was used to identify leukemic LGLs from PBMCs.

Effect of DAC and IL-6 treatment on SOCS3, STAT3, P-STAT3, and Mcl-1 expression and apoptosis of leukemic LGLs. Results were obtained by LGL cultures treated for 96 hours with or without DAC and then stimulated with IL-6 for 1 hour. (A) SOCS3 expression levels in LGLs obtained by RT-PCR and normalized on GAPDH. The results of 4 representative patients are reported. (B) Western blot analysis of LGL extracts for P-STAT3, total STAT3, and SOCS3. β-Actin served as a loading control. Two representative cases of patients are shown. (C) Mcl-1 expression levels obtained by western blot analysis (D) and by RT-PCR of LGLs from a representative patient with LGLL. (E) Annexin V/PI assay measuring LGL mortality percentage (± SE) in PBMC culture after DAC treatment (4 days of incubation) or with AG490, inhibiting STAT3 signaling. A staining with anti-CD57-FITC was used to identify leukemic LGLs from PBMCs.

SOCS3 restoration leads to P-STAT3 and Mcl-1 reduction and LGL apoptosis

To investigate whether, in leukemic LGLs, JAK/STAT signaling was re-established as a consequence of SOCS3 restoration, we tested the modulation of P-STAT3 and Mcl-1 after 1, 3, and 6 hours of LGL culture. We observed that SOCS3, once re-established by DAC and triggered by IL-6, led to a decrease of P-STAT3 after just 1 hour (Figure 5B) and to a progressive decrease of Mcl-1, one of the most important proapoptotic target genes induced by P-STAT3 in LGLL (Figure 5C-D). On the other hand, cells not pretreated with DAC maintained stable or even increased Mcl-1 levels. These data were observed both at the mRNA and protein levels. Moreover, in these experiments, we showed that LGL apoptosis increased after DAC incubation, with a pattern consistent with the addition in the culture of the inhibitor of STAT3 signaling AG490 (Figure 5E).

Methylation analysis of the SOCS3 promoter in leukemic LGLs

To determine whether methylation of the SOCS3 promoter was involved in its expression in leukemic LGLs, we performed MSP of the SOCS3 promoter using genomic DNA isolated from leukemic LGLs and autologous LGL-depleted populations. After total DNA was modified, to discriminate the methylated from the unmethylated promoter sequence, we analyzed a total of 20 samples from patients and an additional 6 samples from healthy individuals by using MSP of the SOCS3 promoter region, comprising nucleotides −525 to −384. The PCR product from the LGLs of patients under study identified only unmethylated sequences in all cases studied. Consistent results were obtained also from the autologous LGL-depleted PBMC population and in control CTLs. Data on 2 representative patients are shown in Figure 6A. These results were confirmed by sequencing assays on 10 patients and 5 control participants (Figure 6B); 44 CpG sites located between nucleotides −678 and −216 of the SOCS3 promoter were tested by bisulfite sequencing. We found that methylation was not detectable in the SOCS3 promoter CpG island of any patient with LGLL.

Methylation of SOCS3 promoter. (A) Methylation-specific PCR of the SOCS3 promoter in LGLs and the autologous LGL-depleted PBMCs of 2 representative patients. M: methylated band and U: unmethylated band. (B) Methylation of CpG dinucleotides. The figure reports the methylation pattern in the promoter region of the SOCS3 gene for 1 representative control participant and 2 representative patients. The filled circles indicate methylated CpG dinucleotides, and the empty circles indicate unmethylated dinucleotides. The numbers indicate the CpG dinucleotide position before the start codon. Analysis of the control participants was performed on the sorted CTLs; in the patients, the analysis was performed on the sorted LGLs. The methylation frequency, for each sequenced clone, was calculated as the number of methylated CpG dinucleotides over the total CpG dinucleotides present in the analyzed sequence. The difference in median methylation frequency was similar both in the patients and in the control participants.

Methylation of SOCS3 promoter. (A) Methylation-specific PCR of the SOCS3 promoter in LGLs and the autologous LGL-depleted PBMCs of 2 representative patients. M: methylated band and U: unmethylated band. (B) Methylation of CpG dinucleotides. The figure reports the methylation pattern in the promoter region of the SOCS3 gene for 1 representative control participant and 2 representative patients. The filled circles indicate methylated CpG dinucleotides, and the empty circles indicate unmethylated dinucleotides. The numbers indicate the CpG dinucleotide position before the start codon. Analysis of the control participants was performed on the sorted CTLs; in the patients, the analysis was performed on the sorted LGLs. The methylation frequency, for each sequenced clone, was calculated as the number of methylated CpG dinucleotides over the total CpG dinucleotides present in the analyzed sequence. The difference in median methylation frequency was similar both in the patients and in the control participants.

Discussion

In our study, we provide evidence that 2 different mechanisms account for the constitutive STAT3 activation in patients with T-LGLL: (1) the high production of IL-6, released by autologous LGL-depleted population of patients' PBMC; and (2) the down-modulation of SOCS3, which is responsible for the lack of the physiological negative feedback mechanism controlling STAT3 activation. An additional finding is represented by the demonstration that in leukemic LGLs, the constitutive activation of STAT3 may be down-modulated by DAC, suggesting a putative role of demethylating agents in LGLL treatment strategies.

The constitutive activation of the JAK/STAT pathway has been claimed to be involved in the development of several human cancers, including hematologic neoplasms (acute myeloid leukemias, Sezary syndrome, multiple myeloma).15,-17 In T-LGLL, Epling-Burnette et al reported that the LGLs from patients constitutively express high levels of activated STAT3 compared with the PBMCs of healthy individuals.4 They also showed that STAT3 activation contributes to Fas resistance, resulting in abnormal survival of leukemic LGLs, and is also responsible for overexpression of the antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1.4 In our study, we confirm that overexpression and activation of STAT3 in T-LGLL is a common feature in all patients with LGLL and extend Epling-Burnette's observation to the comprehension of the mechanisms leading to the constitutive activation of STAT3 in these patients. Interestingly, IL-6 has been demonstrated to play a role in multiple myeloma and in other neoplastic disorders where the JAK/STAT pathway is involved.14,15,37 The evidence that IL-6 is central in inflammatory processes, coupled with the observation that LGLL is often detected in the context of a chronic inflammatory condition, provided the rationale to evaluate whether IL-6 is involved in the pathogenesis of LGLL. Both mRNA expression analysis and the ELISA test indicated that patients’ PBMCs release high amounts of IL-6 compared with healthy individuals, suggesting that activation of STAT3 may result from persistent stimulation of this cytokine. Furthermore, we provided evidence that IL-6 is secreted by a paracrine mechanism, because its production is not the result of leukemic LGLs but of the residual normal autologous LGL-depleted PBMCs. Regarding the source of IL-6, this cytokine is likely released by cells belonging to the monocyte/macrophage lineage. Consistent with this hypothesis, we reported that in the bone marrow of patients with LGLL, dendritic cells and LGLs are in tight contact. Also, it has been suggested that dendritic cells may be the relevant presenting cell that triggers the clonal proliferation and maintains LGL expansion by cytokine production, in particular IL-15.29,38 Taken together, these data highlight the importance of tumor environment39 (ie, ongoing inflammation) in this setting and point out that additional cells, different from the malignant LGL clone, contribute to disease development and maintenance. We also provided evidence that patients’ PBMCs release in vivo high amounts of soluble IL-6Rα, allowing LGLs that do not express IL-6Rα but only gp130, to be responsive to IL-6 through the trans-signaling process.8 This mechanism has been demonstrated in many chronic inflammatory diseases, including chronic inflammatory bowel disease, peritonitis, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, and colon cancer, where IL-6 trans-signaling is critically involved in the maintenance of a disease state by promoting the transition from acute to chronic inflammation.8,-10 The relevant inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation by antibodies against IL-6 or IL-6Rα contributes to the role of IL-6 signaling as one of the central mechanisms in maintaining LGL survival in LGLL.

Interestingly, we found very low expression of SOCS3 in patients’ LGL compared with the CTLs of the control group. Several studies suggested that this feedback loop, which is crucial in controlling the level of STAT3 activation, can be inhibited in some tumors characterized by P-STAT3 overexpression.32,33,36 Comparison between pathological LGLs and the remaining autologous PBMCs indicates that the signaling pattern defined by high P-STAT3 and low SOCS3 expression was a discrete characteristic of leukemic LGsL. This new mechanism in the pathophysiology of LGLs has not been a clear explanation. In fact, sequencing the entire coding region of 27 patients, we excluded the presence of SOCS3 gene mutations and also showed that the promoter was not inactivated via CpG island methylation, as demonstrated in other neoplastic clinical conditions.32,33,36 Consistent with the role of epigenetic gene silencing in LGL disorders, in chronic lymphoproliferative disorders of natural killer (NK) cells, we reported that expression of the inhibitory cytotoxic NK receptors KIR3DL1 was down-modulated by hypermethylation of the promoter.40 This observation supports the possibility that an epigenetic regulatory mechanism may be associated with LGL transformation. In fact, by treating leukemic LGLs with a demethylating agent, SOCS3 expression was restored, with the reappearance of P-STAT3 suppression and inhibition of downstream signals, in particular Mcl-1 expression.41 Although the fine mechanisms tuning out SOCS3 expression have not, up to now, been clarified, for the first time our results demonstrated a link between constitutive STAT3 activation, ultimately resulting in LGL survival, and epigenetic regulatory mechanisms. More interestingly, our data provided evidence of the reversibility of epigenetic inhibition using hypomethylating agents, thus opening the possibility that an epigenetic approach to re-express SOCS3 may be exploited for the treatment of T-LGLL.

It has been recently observed that recurrent somatic missense mutations of STAT3 (more often Y640F and D661Y) might be demonstrated in a fraction (31/77, 40%) of patients with LGLL.25 The same authors updated their case study in more than 100 patients with LGLL, demonstrating that STAT3 mutations were detectable in nearly one third of patients. They reported that the same mutations were also observed in a similar fraction of patients with NK-type LGL lymphoproliferative disease.26 In particular, the Y640F mutation was reported in a human hepatic adenoma causing cytokine-independent tyrosine phosphorylation and cytokine-dependent hyperactivation of STAT3.42 The authors suggested that mutated STAT3 still retains its physiologic ability to stimulate some target genes. However, the putative role of the STAT3 mutation is still controversial. In fact, whereas STAT3 activation is a constitutive mechanism in all patients with T-LGLL,4,25 STAT3 mutations are reported only in nearly one third of cases, despite the presence of monoclonal rearrangement of TCR in all cases.25,26 In addition, considering each patient, STAT3 mutated LGLs have been shown to account for only a fraction of the entire monoclonal LGL population.25 Accordingly, in our series of 27 monoclonal patients analyzed, we found 6 (22.2%) with STAT3 mutations (4 with Y640F and 2 with D661Y). Moreover, in the patients with STAT3 mutations, consistently with the other patients, we observed high expression of P-STAT3 and IL-6, associated with SOCS3 downregulation, ruling out any specific peculiarity in these patients. Several observations might account for the lower number of patients with mutations in our series compared with published series.25,26 The lower number of our patients and different study populations can be taken into consideration. In particular, the more indolent clinical features of our patients compared with those reported by Koskela et al25 and Jerez et al26 represent a plausible explanation. In fact, Jerez et al26 report that patients with indolent features were predominantly grouped with patients without mutation (59 wild-type vs 6 mutant cases), ie, 9% of cases having mutations when only patients with indolent clinical features are being considered, a figure that well compares with that reported in our series (22.2%). In any case, these findings suggest that the acquisition of STAT3 mutations occurs late during the natural history of disease, which is subsequent to establishment of clonality. This event is likely to represent a marker of progression of disease rather than a true pathogenetic process leading to the development of LGLL. Taking together, these results indicate that genomic mutations might only marginally account for in vivo activation of STAT3 in patients with LGLL and further emphasize the heterogeneity of mechanisms sustaining LGLL, highlighting the plasticity of proliferating cells.43

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro, Cariparo, Cariverona, Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca Scientifica, and Lions Club International. A.T., F.Passeri, and E.B. were the recipients of a fellowship from Associazione Italiana contro le Leucemie, Linfomi e Mieloma and the Lions Club, Padua. V.T. received a fellowship from the Venetian Institute of Molecular Medicine and E.A. from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro.

Authorship

Contribution: A.T. designed the research, performed some of the in vitro research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; C.G. performed some of the in vitro research and participated in data analysis; F.Passeri, A.L., G.T., F.F., V.M., and V.T. performed some of the in vitro research; E.A. performed sequencing analysis; A.C. and E.B. performed cytofluorimetry studies; F.Piazza, M.F., and L.T. contributed to data analysis; G.S. provided funding, participated in data analysis, and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript; and R.Z. designed the study, analyzed data, wrote the manuscript, and supervised the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gianpietro Semenzato, Department of Medicine, University of Padua, Hematology and Clinical Immunology Branch, Via Giustiniani 2, 35128 Padova, Italy; e-mail: g.semenzato@unipd.it.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal