Abstract

Platelets survey blood vessels, searching for endothelial damage and preventing loss of vascular integrity. However, there are circumstances where vascular permeability increases, suggesting that platelets sometimes fail to fulfill their expected function. Human inflammatory arthritis is associated with tissue edema attributed to enhanced permeability of the synovial microvasculature. Murine studies have suggested that such vascular leak facilitates entry of autoantibodies and may thereby promote joint inflammation. Whereas platelets typically help to promote microvascular integrity, we examined the role of platelets in synovial vascular permeability in murine experimental arthritis. Using an in vivo model of autoimmune arthritis, we confirmed the presence of endothelial gaps in inflamed synovium. Surprisingly, permeability in the inflamed joints was abrogated if the platelets were absent. This effect was mediated by platelet serotonin accumulated via the serotonin transporter and could be antagonized using serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitor antidepressants. As opposed to the conventional role of platelets to microvascular leakage, this demonstration that platelets are capable of amplifying and maintaining permeability adds to the rapidly growing list of unexpected functions for platelets.

Introduction

Platelets patrol blood vessels seeking vascular injuries. When damage to the endothelium is detected, platelets promptly aggregate and release mediators to prevent blood loss and promote wound repair.1 In addition to their role in primary hemostasis, platelets also protect the vasculature against leakage.2 Indeed, although basal levels of vascular permeability is necessary to allow the passage of small molecules, such as nutrients, ions, and water, the ultrastructural changes to the endothelium that accompany thrombocytopenia prompt vasculature leakage and can lead to edema or uncontrolled bleedings.2-6 Further, induction of thrombocytopenia engenders hemorrhages localized at the site of inflammation during Arthus reaction, stroke, sunburn, and endotoxin-induced lung inflammation,7,8 pointing to a critical role of platelets in maintenance of blood vessels in inflammatory conditions.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common autoimmune inflammatory disorder that affects the joints.9 The presence of microvascular injuries in joints of patients with RA has long been appreciated.10,11 Transcellular fenestrations and interstices between endothelial cells, called gaps, are frequently observed in RA synovium vasculature and contribute to the enhanced permeability of the diseased joint.10,12-16 Importantly, the permeability that preferentially arises in joints during experimental arthritis has been proposed to contribute to the organ preference of autoimmune inflammatory arthritis.17,18

During murine autoimmune arthritis, platelets are activated through collagen receptor glycoprotein VI (GPVI) and release platelet microparticles (MPs), submicron vesicles shed from platelet surface.19 These MPs are enriched in the inflammatory cytokine IL-1 and can exacerbate inflammation by stimulating resident fibroblast and potentially other cells. Notwithstanding the role of platelets in inflammation, the permeability that prevails in the joint vasculature during arthritis evidences the inability of platelets to preserve the vessel wall integrity during this disease. Herein, we aimed to specifically scrutinize the role of platelets in the maintenance of the endothelial barrier function in arthritis disease while the inflammation is in place. We observed that, rather than preserving vascular integrity during arthritis, platelets enhance the formation of interendothelial cell gaps in joints via serotonin.

Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Fluorescent Sky Blue and Nile Red polystyrene microspheres were obtained from Spherotech. Various sizes were used: 0.04 to 0.09 μm (mean, 0.09 μm), 0.1 to 0.3 μm (mean, 0.22 μm), 0.4 to 0.6 μm (mean, 0.45 μm), 0.7 to 0.9 μm (mean, 0.84 μm), 2.5 to 4.5 μm (mean, 3.2 μm), and 10.0 to 14.0 μm (mean, 10.2 μm). Antibody preparation for mouse platelet depletion (a mixture of purified rat monoclonal antibodies directed against mouse GPIb [CD42b]) and polyclonal nonimmune rat immunoglobulins were obtained from Emfret Analytics. Purified Rat Anti-Mouse Ly-6G and Ly-6C and Purified Rat IgG2b (Isotype Control) were obtained from BD Biosciences. The cross-linked form of collagen-related peptide (CRP, Gly-Cys-Hyp-(Gly-Pro-Hyp)10-Gly-Cys-Hyp-Gly) was generated as described.20 Serotonin hydrochloride was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Mouse recombinant IL-1β was obtained from Cedarlane. Dextran-fluorescein 40 000 molecular weight was obtained from Life Technologies.

Human SF

Human knee synovial fluids (SFs) were obtained as discarded material from patients with various arthritides undergoing diagnostic or therapeutic arthrocentesis. Arthritis diagnosis was ascertained by an American Board of Internal Medicine–certified rheumatologist and/or by review of laboratory, radiologic, and clinic notes and by applying ACR classification criteria. All studies received Laval University Institutional Review Board approval.

Mice

We used 6- to 9-week-old mice for all of our studies. Guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care were followed in a protocol approved by the Animal Welfare Committee at Laval University. C57BL/6J, Slc6a4 (solute carrier family 6 member 4; also called serotonin transporter [SERT]) null mice (backcrossed to C57BL/6J > 10 times) and KitW-sh mutant mice (87% C57BL/6J genetic background) and their age- and sex-matched controls were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. BALB/c mice were obtained from Charles River. LysM-eGFP breeders were obtained from Dr Gregory Dekaban (Robarts Institute, London, ON), with authorization from Dr Thomas Graf (Barcelona, Spain). LysM-eGFP mice showed specific green fluorescence in macrophages and neutrophil granulocytes.21 When microspheres were used, 1 μg of the microspheres was injected intravenously (100 μL/mice). Platelet depletion was achieved by injecting 4 μg/g of depleting antibody or matched isotype antibody to mice as described by the manufacturer (Emfret). These antibodies were administrated one hour before K/BxN injection and at day 3 for arthritis experiments or 18 hours before K/BxN injection in flare experiments. When mouse recombinant IL-1β was administrated, it was injected intraperitoneally in mice receiving the platelet-depleting antibody 4 hours before K/BxN injection and on day 1 and 2 (2 μg per injection). Gr1 cell depletion was achieved by intraperitoneal injection of 100 μg isotype control or Ly-6G and Ly-6C antibody to arthritic mice in combination with 2.5 μg IL-1β at day 7 after K/BxN injection for arthritis experiments or 18 hours before K/BxN injection for flare experiments. Efficient Gr1 cell depletion was confirmed by leukocyte counts in experimental animals. For the GPVI stimulation in vivo, CRP-XL (40 μg/kg) was injected intravenously 30 minutes before microsphere injection. Serotonin was dissolved in normal sterile saline and was administrated at 20 mg/kg intravenously 5 minutes before microsphere injection. Dextran-fluorescein was dissolved in normal saline and was administrated at 40 mg/kg intravenously 2 minutes before the microsphere injection.

Serum transfer protocol and arthritis scoring

Arthritogenic K/BxN serum was transferred to recipient C57BL/6J, LysM-eGFP, and BALB/c mice via intraperitoneal injection (125, 125, and 75 μL K/BxN serum, respectively) on experimental day 0 and day 2 to induce arthritis as described.19 Ankle thickness was measured at the malleoli with the ankle in a fully flexed position, using a spring-loaded dial caliper (DGI Supply). For flare experiments, the K/BxN serum was transferred to recipient mice via intravenous injections (100 μL/mouse).

Pharmacologic inhibition of SERT

When fluoxetine was used in vivo, the drug was dissolved at 160 mg/L in drinking water and changed once per week for 3 weeks before the administration of K/BxN serum. When bolus administration of fluoxetine was used, the drug was administrated by intraperitoneal injection (2.5 mg/kg) in arthritic mice one hour before the microsphere injection.

Determination of serotonin content

Mouse blood was drawn by cardiac puncture using acid citrate dextrose anticoagulant (0.085M sodium citrate, 0.0702M citric acid, 0.111M dextrose, pH 4.5). Blood was diluted by addition of 300 μL Tyrode buffer, pH 6.5 (134mM NaCl, 2.9mM KCl, 0.34mM Na2HPO4, 12mM NaHCO3, 20mM HEPES, 1mM MgCl2, 5mM glucose, 0.5 mg/mL BSA) and centrifuged at 600g for 3 minutes. The platelet-rich plasma was further centrifuged for 2 minutes at 400g to pellet contaminating RBCs. The platelet-rich plasma was thereafter centrifuged for 5 minutes at 1300g to pellet platelets. Platelets were lysed by addition of buffer (20mM Tris HCl, pH 7.8, 1.25mM EDTA, 120mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40, 0.5% Triton; Complete Protease inhibitor, Roche; PhosSTOP Phosphatase inhibitor, Roche; and 0.5mM PMSF). The serotonin content in platelet lysates and in mouse whole blood was measured using serotonin ELISA Kit (Fitzgerald Industries International). The serotonin content in SF of human patients affected by RA and osteoarthritis (OA) was measured using serotonin (ultrasensitive) ELISA Kit (Fitzgerald Industries International).

Fluorescence imaging

Mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane in O2 and placed inside an in vivo imaging system Xenogen IVIS200 (Xenogen) 2 to 45 minutes after the injection of microspheres. The excitation filter was 615 to 665 nm, the emission filter was 695 to 770 nm, and the acquisition time was 2 seconds. The images were analyzed using Living Image Version 4.0 software. A Region of Interest tool was used to measure the radiant efficiency from each ankle and compared with control ankles in conditions where the highest specific signal-to-background ratio was achieved. The radiant efficiency was also examined in externalized harvested heart, kidney, liver, spleen, and lung in all animal groups.

Electron microscopy analysis

RA patients underwent a Parker-Pearson needle biopsy of the synovium. Specimens were immediately placed into half-strength Karnovsky paraformaldehyde-glutaraldehyde fixative for electron microscopy. Specimens were postfixed in cold Palade osmium-veronal and embedded in epoxy resin. Thick sections were obtained, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined on a Zeiss EM 10 electron microscope under a 50-kV beam.

Multiphoton microscopy

Arthritic and nonarthritic control LysM-eGFP mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and immobilized in the supine position, and a midline incision was performed along the malleolus of the ankle. A 6-0 silk suture (Ethicon) was used to gently spread the skin to maximize the imaging area. The whole setup was placed on the stage underneath the objective, and a 0.9% saline solution was applied over the region to be imaged. Dextran conjugated with fluorescein and Nile Red polystyrene microspheres (size 0.4-0.6 μm) were injected 5 minutes before the beginning of the imaging session to visualize blood vessels and blood vessel permeability, respectively. Body temperature was recorded through a rectal probe connected to a temperature controlling device (RWD Life Science Co), and the temperature was maintained at 37°C during all procedures.

All images were acquired on an Olympus FV1000 MPE 2-photon microscope dedicated to intravital imaging. The 2-photon Mai Tai DeepSee laser (Spectra-Physics, Newport Corp) was tuned at 950 nm for all experiments. Tissues were imaged using an Olympus Ultra 25x MPE water immersion objective (1.05 NA), with filter set bandwidths optimized for CFP (460-500 nm), YFP (520-560 nm), and Texas Red/DsRed (575-630 nm) imaging. Detector sensitivity and gain were set to achieve the optimal dynamic range of detection. Using Olympus Fluoview Version 3.0a software, images with a resolution of 256 × 256 pixels were acquired at different zoom factors (2-4×) at 2.5 frames per second with auto-HV option enabled, and exported as 24-bit RGB TIF files, whereas metadata for subsequent automatic setting-detection were exported in a TXT file. No Kalman filter was used to avoid slowing down the acquisition speed.

Statistical analysis

Results of mouse arthritis experiments are presented as mean plus or minus SEM. The statistical significance for comparisons between groups was determined using 2-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni correction. Statistical significance for experiments using radiant efficiency and ELISA was determined using unpaired Student t test. All statistical analysis was done using Prism software package Version 4.00 (GraphPad Software).

Results

Vascular permeability occurs in joints during arthritis

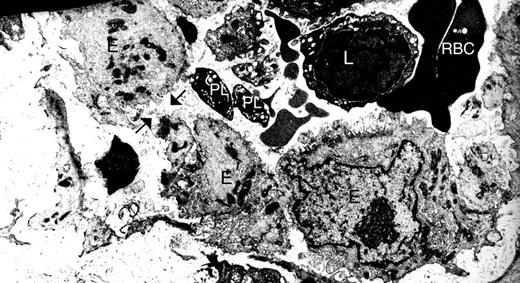

For this study, we aimed to examine platelets in a context where increased vasculature permeability and inflammation are present. Gaps are found between endothelial cells in the synovial vasculature from patients with RA,10 and our electron microscopic analyses of synovial tissues from these patients also reveal platelets in the vicinity of these gaps10 (Figure 1). Thus, autoimmune inflammatory arthritis appeared to us as an ideal condition to investigate the role of platelets in the context of enhanced vasculature permeability.

Gaps are present between endothelial cells in the synovium vasculature from patients with RA. Synovium from RA patients was scrutinized by electron microscopy. Black arrows indicate one gap between endothelial cells. E indicates endothelial cells; PL, platelets; L, lymphocytes; and RBC, red blood cells. Original magnification ×48 400.

Gaps are present between endothelial cells in the synovium vasculature from patients with RA. Synovium from RA patients was scrutinized by electron microscopy. Black arrows indicate one gap between endothelial cells. E indicates endothelial cells; PL, platelets; L, lymphocytes; and RBC, red blood cells. Original magnification ×48 400.

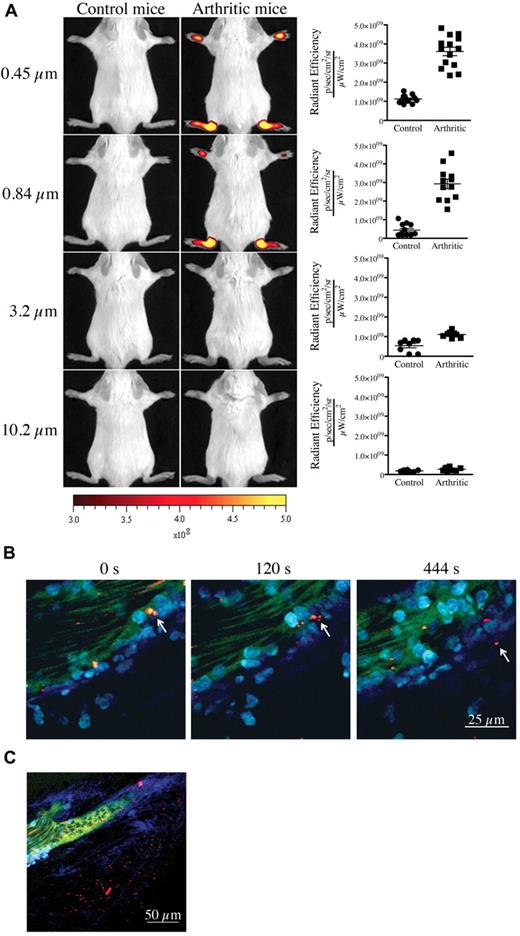

We first confirmed the presence of vasculature leakage in joints during active arthritis. We used the K/BxN serum transfer model of inflammatory arthritis for our studies. In this model, arthritis can be induced by passive transfer of autoantibody-containing serum from K/BxN mice into wild-type mice.22 To visualize the formation of interendothelial cell gaps and to obtain an estimate of their width during arthritis in vivo, we injected fluorescent microspheres of various diameters (0.09-10.2 μm) intravenously into control mice and mice at the peak of arthritis disease (day 7 after K/BxN serum injection) and monitored their localization using in vivo imaging. Although none of the microspheres could reach the joints of control nonarthritic mice, microspheres of diameter 0.84 μm, 0.45 μm (Figure 2A), 0.22 μm and 0.09 μm (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) promptly and preferentially localized to arthritic joints (supplemental Figure 2A). Entry was direct and not via attachment to migrating neutrophils (supplemental Figure 2B-C). Using intravital 2-photon microscopy, we further validated the microsphere egress from blood vessels and their concomitant accumulation within the collagen mesh where the inflammation culminated (Figure 2B-C; full resolution video available at http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/content/early/2012/04/27/blood-2012-02-413047/suppl/DC1). Importantly, those microspheres having diameters of 3.2 μm and 10.2 μm failed to reach the arthritic joints (Figure 2A), showing that gaps in joint vasculature during arthritis enable passive influx only of particles of submicron dimension.

Presence of vasculature permeability during autoimmune arthritis in vivo. (A) Nonarthritic control (left) and arthritic (right) mice (day 7 after K/BxN serum injection) were injected intravenously with 0.45-, 0.84-, 3.2-, or 10.2-μm-diameter microspheres and visualized 5 minutes later using a Xenogen IVIS in vivo imaging system. Control and arthritic mice received the same concentration of fluorescent microspheres. Radiant efficiency quantifications in the ankle joints for control and arthritic mice for all microsphere sizes are presented at right. (B-C) In vivo 2-photon imaging of the vasculature permeability in the arthritic ankle joint. LysM-eGFP arthritic mice injected intravenously with dextran-fluorescein and 0.45 μm Nile-Red-conjugated microspheres, and ankle joints were imaged to visualize the microsphere egress from the blood circulation and accumulation in the subendothelial collagen-rich matrix. (B) Two-photon images from time-lapse recordings taken at 0, 120, and 444 seconds demonstrating a microsphere leaving the blood circulation independently of transportation by a neutrophil or a monocyte. (C) Representative image evidencing the accumulation of microspheres outside the vasculature in an arthritic joint. Red represents microspheres; green, blood vessels; cyan blue, leukocytes; and Indigo blue, collagen (second-harmonic generation). Scale bar represents 25 μm (panel B), and 50 μm (panel C).

Presence of vasculature permeability during autoimmune arthritis in vivo. (A) Nonarthritic control (left) and arthritic (right) mice (day 7 after K/BxN serum injection) were injected intravenously with 0.45-, 0.84-, 3.2-, or 10.2-μm-diameter microspheres and visualized 5 minutes later using a Xenogen IVIS in vivo imaging system. Control and arthritic mice received the same concentration of fluorescent microspheres. Radiant efficiency quantifications in the ankle joints for control and arthritic mice for all microsphere sizes are presented at right. (B-C) In vivo 2-photon imaging of the vasculature permeability in the arthritic ankle joint. LysM-eGFP arthritic mice injected intravenously with dextran-fluorescein and 0.45 μm Nile-Red-conjugated microspheres, and ankle joints were imaged to visualize the microsphere egress from the blood circulation and accumulation in the subendothelial collagen-rich matrix. (B) Two-photon images from time-lapse recordings taken at 0, 120, and 444 seconds demonstrating a microsphere leaving the blood circulation independently of transportation by a neutrophil or a monocyte. (C) Representative image evidencing the accumulation of microspheres outside the vasculature in an arthritic joint. Red represents microspheres; green, blood vessels; cyan blue, leukocytes; and Indigo blue, collagen (second-harmonic generation). Scale bar represents 25 μm (panel B), and 50 μm (panel C).

Platelets promote vascular permeability in inflamed vasculature

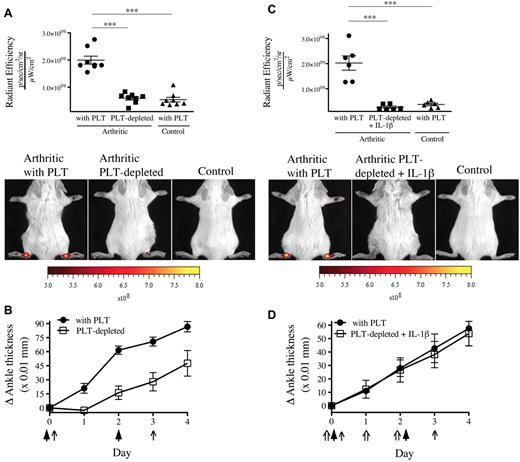

Because one function of platelets is to maintain microvascular integrity, platelet depletion would be expected to exacerbate vascular permeability. We therefore evaluated the contribution of platelets to the prevention of endothelial gap formation during arthritis using thrombocytopenic mice. We found a complete abrogation of gaps in the absence of platelets (Figure 3A). Given that platelet MPs can provide IL-1 and so exacerbate arthritis,19 this reduction in gap production could have resulted from an overall diminution of inflammation (Figure 3B). However, in opposition to the striking blockade of vascular leakage, the arthritis severity in absence of platelets was only partially reduced, pointing to the uncoupling of inflammation and permeability. To maintain inflammation despite platelet depletion, we thus injected recombinant IL-1β concurrently to the K/BxN serum and monitored gap formation.23,24 Surprisingly, we observed that the permeability in joints remained suppressed in mice lacking platelets, even in experimental conditions where severe inflammation is maintained (Figure 3C-D).

The presence of gaps in the inflamed arthritic joint vasculature depends on platelets. (A) The platelet-depleting antibody or the isotype control antibody was injected to mice on day 0 and day 3. Arthritis was induced by injection of 75 μL of K/BxN serum on day 0 and day 2. On day 4, the 0.45-μm microspheres were intravenously injected in platelet (PLT)–depleted mice and control mice (with PLT), and the fluorescence was measured in ankle joints 5 minutes later. Nonarthritic mice were used as controls. Representative results are presented. ***P < .0001. (B) The signs of arthritis were monitored daily and presented as mean ± SEM. Arrow indicates parenteral administration of platelet-depleting antibody or isotypic control; and arrowheads, K/BxN serum administration. (C) Antibody injection, arthritis induction, microsphere injection, fluorescence measurements, controls, and results presentation were performed as in panel A. Mouse recombinant IL-1β was injected on days 0, 1, and 2 in mice receiving the platelet-depleting antibody. ***P = .0002 (top). ***P = .0001 (bottom). (D) The signs of arthritis were monitored as in panel B. Arrow indicates parenteral administration of platelet-depleting antibody or isotypic control; arrowheads, K/BxN serum administration; and double arrow, IL-1β administration.

The presence of gaps in the inflamed arthritic joint vasculature depends on platelets. (A) The platelet-depleting antibody or the isotype control antibody was injected to mice on day 0 and day 3. Arthritis was induced by injection of 75 μL of K/BxN serum on day 0 and day 2. On day 4, the 0.45-μm microspheres were intravenously injected in platelet (PLT)–depleted mice and control mice (with PLT), and the fluorescence was measured in ankle joints 5 minutes later. Nonarthritic mice were used as controls. Representative results are presented. ***P < .0001. (B) The signs of arthritis were monitored daily and presented as mean ± SEM. Arrow indicates parenteral administration of platelet-depleting antibody or isotypic control; and arrowheads, K/BxN serum administration. (C) Antibody injection, arthritis induction, microsphere injection, fluorescence measurements, controls, and results presentation were performed as in panel A. Mouse recombinant IL-1β was injected on days 0, 1, and 2 in mice receiving the platelet-depleting antibody. ***P = .0002 (top). ***P = .0001 (bottom). (D) The signs of arthritis were monitored as in panel B. Arrow indicates parenteral administration of platelet-depleting antibody or isotypic control; arrowheads, K/BxN serum administration; and double arrow, IL-1β administration.

Platelet-derived serotonin triggers gap formation

Platelets play a crucial role in hemostasis by preserving the integrity of the vasculature.2 Therefore, how could the platelets contribute to the increased joint permeability during arthritis? Given its abundance in platelets, serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) was initially detected in blood,25 and studies have examined its function(s) in vascular permeability26,27 and joint edema.17 A pioneering electron microscopic investigation showed that local injection of serotonin in the cremaster muscle induced the formation of gaps, 0.1 to 0.8 μm in width, between endothelial cells.26 Interestingly, the authors frequently observed the presence of platelets, sometimes bridging these gap, sometimes plugging them, and also noticed disintegrating platelets near these gaps.26 Given the striking similarities between the gaps observed in RA synovium10 (Figure 1A) and those observed after serotonin injection,26 we hypothesized that platelets may promote the gap formation via serotonin.

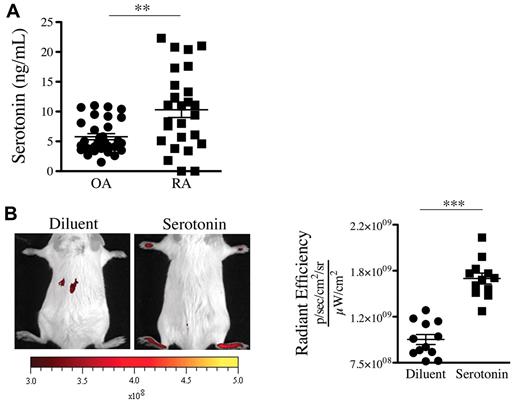

We thus sought to determine the presence of serotonin in joint fluids where platelets are present. In contrast to the SF of patients with OA, the SF of patients with RA contains platelet MPs,19 a hallmark of platelet activation. Consistent with presence of MPs in RA SF, we measured an average of 10.3 ng/mL serotonin in SF from RA patients (Figure 4A). Interestingly, lower levels of serotonin were measured in the SF of patients with OA (Figure 4A). We next evaluated whether serotonin could promote the formation of gaps in mouse joints. We found that a single systemic injection of serotonin to nonarthritic mice sufficed to promote formation of gaps in joint vasculature (Figure 4B), independently of neutrophils (supplemental Figure 2D).

Serotonin is present in the SF of patients with RA and can promote the gap formation in joint vasculature. (A) Serotonin concentrations were measured in SF of RA and OA patients using an ELISA serotonin kit (n = 27). **P = .0012. (B) Serotonin suffices to promote prompt formation of gaps in joints. Diluent (PBS) or serotonin (20 mg/kg) was injected intravenously in mice before administration of 0.45-μm-diameter fluorescent microspheres. The fluorescence was portrayed using an in vivo imaging system 45 minutes after the microsphere injection (left). The radiant efficiency quantifications in the ankle joints for control (diluent) and serotonin injections are presented on the right. ***P < .0001; *P = .024.

Serotonin is present in the SF of patients with RA and can promote the gap formation in joint vasculature. (A) Serotonin concentrations were measured in SF of RA and OA patients using an ELISA serotonin kit (n = 27). **P = .0012. (B) Serotonin suffices to promote prompt formation of gaps in joints. Diluent (PBS) or serotonin (20 mg/kg) was injected intravenously in mice before administration of 0.45-μm-diameter fluorescent microspheres. The fluorescence was portrayed using an in vivo imaging system 45 minutes after the microsphere injection (left). The radiant efficiency quantifications in the ankle joints for control (diluent) and serotonin injections are presented on the right. ***P < .0001; *P = .024.

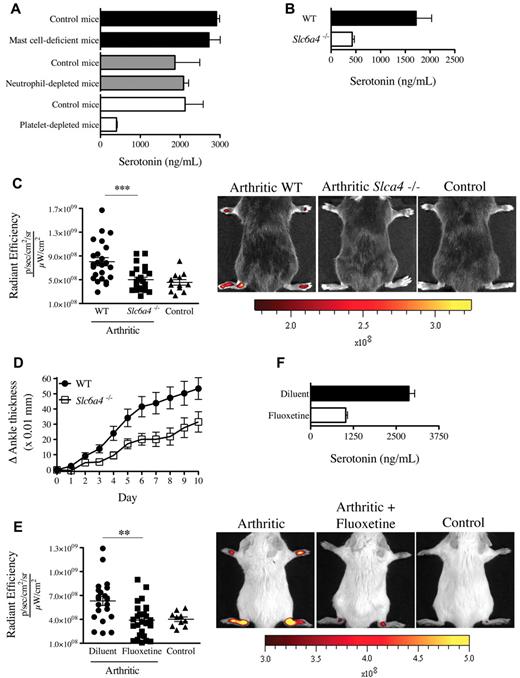

Although the enterochromaffin cells in the gastrointestinal tract are the main biosynthetic source of serotonin,28 the expression of SERT enables platelets to store serotonin.29 We thus validated the role of platelets in serotonin transport and used neutrophil-depleted mice and mast cell-deficient mice (KitW-sh) for comparison. We find that, in contrast to blood from mast cell-deficient mice and neutrophil-depleted mice, blood from platelet-depleted mice contained no detectable serotonin (Figure 5A). Further, although the production of serotonin by the intestine is intact in SERT deficient mice (Slc6a4−/−),30 the platelets isolated from these mice contained only minimal serotonin levels (Figure 5B). Thus, compatible with the existing literature on platelet serotonin,29 our results confirm that platelets require the expression of SERT to operate as serotonin's main vehicle in blood.

Mice deficient in platelet-derived serotonin have reduced gap formation. (A) Serotonin concentrations were measured in whole blood from mast cell-deficient mice (KitW-sh), neutrophil-depleted mice, platelet-depleted mice, and their corresponding control mice using an ELISA serotonin kit. (B) Serotonin concentration was measured in platelet isolated from WT and Slc6a4−/− mice. (C) WT and Slc6a4−/− arthritic mice were injected intravenously with 0.45-μm-diameter fluorescent microsphere, and the fluorescence was visualized 5 minutes later using an in vivo imaging system. Control mice (WT nonarthritic) and WT and Slc6a4−/− arthritic mice all received the same concentration of fluorescent microspheres. The radiant efficiency quantifications in the ankle joints for all mice are presented, and representative results are presented at right. ***P = .004. (D) Mice (17/group) sufficient and deficient in SERT expression were injected with 125 μL K/BxN serum at day 0 and day 2 and the signs of arthritis monitored daily. The mouse arthritis experiment is presented as mean ± SEM. P < .01. (E) SERT pharmacologic inhibition was performed in C57BL/6J mice by treating the mice with fluoxetine for 21 days before administration of K/BxN serum. Arthritic (treated or not with fluoxetine) and control (nonarthritic) mice were injected intravenously with 0.45-μm-diameter fluorescent microsphere, and the fluorescence was visualized 5 minutes later using an in vivo imaging system. The radiant efficiency quantifications in the ankle joints for all mice are presented, and representative results are presented at right. **P = .0092. (F) Serotonin concentrations in platelets isolated from mice treated or not with fluoxetine were measured by ELISA.

Mice deficient in platelet-derived serotonin have reduced gap formation. (A) Serotonin concentrations were measured in whole blood from mast cell-deficient mice (KitW-sh), neutrophil-depleted mice, platelet-depleted mice, and their corresponding control mice using an ELISA serotonin kit. (B) Serotonin concentration was measured in platelet isolated from WT and Slc6a4−/− mice. (C) WT and Slc6a4−/− arthritic mice were injected intravenously with 0.45-μm-diameter fluorescent microsphere, and the fluorescence was visualized 5 minutes later using an in vivo imaging system. Control mice (WT nonarthritic) and WT and Slc6a4−/− arthritic mice all received the same concentration of fluorescent microspheres. The radiant efficiency quantifications in the ankle joints for all mice are presented, and representative results are presented at right. ***P = .004. (D) Mice (17/group) sufficient and deficient in SERT expression were injected with 125 μL K/BxN serum at day 0 and day 2 and the signs of arthritis monitored daily. The mouse arthritis experiment is presented as mean ± SEM. P < .01. (E) SERT pharmacologic inhibition was performed in C57BL/6J mice by treating the mice with fluoxetine for 21 days before administration of K/BxN serum. Arthritic (treated or not with fluoxetine) and control (nonarthritic) mice were injected intravenously with 0.45-μm-diameter fluorescent microsphere, and the fluorescence was visualized 5 minutes later using an in vivo imaging system. The radiant efficiency quantifications in the ankle joints for all mice are presented, and representative results are presented at right. **P = .0092. (F) Serotonin concentrations in platelets isolated from mice treated or not with fluoxetine were measured by ELISA.

We therefore explored the contribution of SERT to gap formation during arthritis using Slc6a4−/− mice. Interestingly, we found that these mice exhibited a profound defect in gap formation and a consistent, yet modest, reduction in arthritis severity (Figure 5C-D). Serotonin modulates a diversity of neuropsychologic processes, and there exist a variety of drugs used in psychiatry that target its uptake.31 Mice pretreated with the antidepressant SERT inhibitor fluoxetine exhibited a significant decrease in gap formation in the course of arthritis (Figure 5E), compatible with the reduced serotonin levels in platelets from these mice (Figure 5F). Consistent with platelet half-life (4-5 days) and their constant storage of serotonin, a single administration of fluoxetine was not sufficient to affect the production of gaps in arthritic mice and the serotonin level in platelets (supplemental Figure 3A-B). Taken together, these results point to a role of platelet serotonin in the formation of gaps during arthritis.

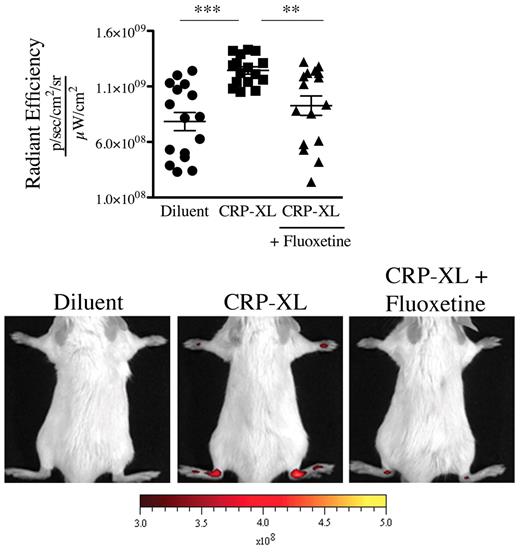

GPVI is a platelet collagen receptor, and its stimulation is reported to promote release of serotonin and MPs from platelets.19,32 We aimed to determine whether GPVI activation could promote vasculature leakage in mouse distal joints. We therefore stimulated GPVI by intravenously injecting the specific GPVI agonist, the CRP-XL,33 to mice and monitored the joint localization of the microspheres. We found that this in vivo stimulation of platelet GPVI sufficed to trigger the gap formation in joints (Figure 6). Importantly, no gaps were produced when the GPVI stimulation was carried out in mice treated with fluoxetine (Figure 6), demonstrating that platelet GPVI stimulation induces the formation of gaps in joints via release of serotonin.

GPVI activation induces the formation of gaps in joints via release of serotonin. Nonarthritic mice (treated or not with fluoxetine for 21 days) were injected intravenously with CRP (40 μg/kg) or its diluent PBS. Thirty minutes after the CRP injection, the 0.45-μm fluorescent microspheres were injected. Two minutes after the microsphere injections, the fluorescence in ankle joints was evaluated using an in vivo imaging system. The radiant efficiency quantifications in the ankle joints for all mice and representative results are presented. ***P < .0001; **P = .0019.

GPVI activation induces the formation of gaps in joints via release of serotonin. Nonarthritic mice (treated or not with fluoxetine for 21 days) were injected intravenously with CRP (40 μg/kg) or its diluent PBS. Thirty minutes after the CRP injection, the 0.45-μm fluorescent microspheres were injected. Two minutes after the microsphere injections, the fluorescence in ankle joints was evaluated using an in vivo imaging system. The radiant efficiency quantifications in the ankle joints for all mice and representative results are presented. ***P < .0001; **P = .0019.

Discussion

Maintenance of vasculature integrity and prevention of fluid leakage in interstitial tissue are a defined function of circulating platelets. To our surprise, we revealed a counterintuitive role for platelets in arthritis, namely, that platelets are the major cause of joint vasculature permeability via serotonin release, potentially serving to promote disease.17,18

Herein, we aimed to study the role of platelets in leakage of the inflamed vasculature. Despite the absence of detectable vasculature permeability in joints of IL-1β–injected thrombocytopenic mice and SERT-deficient mice, the arthritis persisted in these animals, as measured via evaluation of the ankle thickness (an indication of inflammation and tissue remodeling). This suggests that the endothelial gaps in the joint vasculature may not be a prerequisite for progression to inflammation where the concentrations of inflammatory cytokines are excessively elevated. Indeed, neutrophils are capable of migrating through the endothelial barrier in the absence of permeability,34 and many effector cells, such as synovial fibroblasts35 and mast cells,23,36 are already localized in the joints. We thus exploited this conditional independence of inflammation and vasculature permeability to delineate the role of platelets in vascular leakage while severe inflammation is present. We revealed that platelets could induce vascular leak via serotonin, a process inhibited by serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitor antidepressants.

The critical role of platelets in vasculature leakage may not be unique to inflammatory arthritis. In models of lung inflammation induced by acid or abdominal sepsis, platelet depletion prevents both inflammation and vascular leakage,37-39 pointing to a potential role of platelets in vascular permeability during lung inflammation. However, it remains unclear whether leakage occurring in lungs is mediated directly by a platelet-derived mediator or via the overall enhancement of inflammation by platelets. Importantly, we identified serotonin as a platelet-derived mediator able to initiate the formation of gaps in the vasculature during inflammation. In addition to its function in the joint vasculature, serotonin also promotes leakage of endothelial cells in culture and of the vasculature in vivo when locally injected in the cremaster muscle, the footpad, or the cerebral ventricular system,26,40-45 suggesting that serotonin may indeed initiate the formation of gaps between endothelial cells elsewhere, not solely in the synovial vasculature during arthritis.

How did platelets evolve to enhance vasculature permeability? There is a growing appreciation of the immune functions of platelets.46 In contrast to leukocytes, platelets cannot actively exit the vasculature to fight an infection. Our work described herein demonstrates the capability of platelets to open in the vasculature gaps of dimensions compatible with the extravasation of platelet MPs.47 Lacking any notable migratory activity, a platelet could open the endothelial wall and infuse its mediators and MP cargo through the gaps. However, the gaps formed in joint vasculature during autoimmune arthritis may be detrimental to the joint. Like the IL-1–rich platelet MPs,19 immune complexes, the etiologic agent in RA, are also of submicron dimensions, with diameters varying between 0.1 μm and approximately 1 μm.47 It is thus plausible that the gaps produced by platelets contribute to joint invasion by both immune complexes and MPs, supporting a dual contribution to joint inflammation.

Thereby, our demonstration that serotonin uptake by platelets is a prerequisite for the promotion of joint permeability implies that medications used to treat depression by targeting SERT may also target vasculature permeability in RA disease. A clinical observation supporting this notion in exists,48 although whether the drug regimen followed by the arthritic, depressed patient suffices to efficiently deplete serotonin from platelets and impact the severity of arthritis remains to be explored.

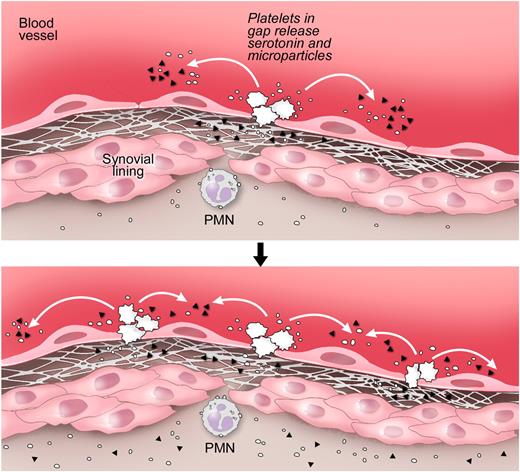

An earlier report showed that the rapid microvasculature permeability, also called flare, which occurs immediately (within minutes) after K/BxN serum injection and goes on approximately 7 minutes, relies on neutrophils and mast cells.17,49 Our findings are complementary to this report. Indeed, we found that this initial event is independent of the presence of platelets and expression of SERT (supplemental Figure 4A-B). Because mast cells also require the expression of SERT to store serotonin,30 our observations that SERT is dispensable during the flare rule out the contribution of mast cell-derived serotonin to the initial gap production that occurs rapidly after K/BxN serum injection. We also examined the role of mast cells in gap formation in the course of arthritis disease (day 7 after K/BxN serum injection). We found that the mast cell-deficient mice showed no defect in gap formation during arthritis (supplemental Figure 5), precluding an obligate function for mast cell SERT in gap production. These results indicate that platelets, not mast cells, fulfill a role in the continuous vasculature permeability that occurs once the disease has been well established (Figure 7, schematic representation).

Proposed pathway for the formation of gaps and amplification of the vasculature permeability by platelets during arthritis. Top panel: Gaps between endothelial cells in arthritic joints are formed. The GPVI-expressing platelets are activated by the newly exposed subendothelial matrix rich in GPVI ligands, such as collagen and laminin. Bottom panel: Stimulated platelets produce copious amounts of IL-1–rich microparticles and release serotonin. Platelet-derived serotonin promotes the production of additional gaps; thus, more platelets can be activated. Serotonin at the site of inflammation promotes the vasculature leakage during disease. Note that the precise anatomic location of platelet activation and the route by which microparticles enter the joint remain speculative. ▴ represents serotonin; and ○, platelet microparticle. Illustration courtesy of Steve Moskowitz, Advanced Medical Graphics.

Proposed pathway for the formation of gaps and amplification of the vasculature permeability by platelets during arthritis. Top panel: Gaps between endothelial cells in arthritic joints are formed. The GPVI-expressing platelets are activated by the newly exposed subendothelial matrix rich in GPVI ligands, such as collagen and laminin. Bottom panel: Stimulated platelets produce copious amounts of IL-1–rich microparticles and release serotonin. Platelet-derived serotonin promotes the production of additional gaps; thus, more platelets can be activated. Serotonin at the site of inflammation promotes the vasculature leakage during disease. Note that the precise anatomic location of platelet activation and the route by which microparticles enter the joint remain speculative. ▴ represents serotonin; and ○, platelet microparticle. Illustration courtesy of Steve Moskowitz, Advanced Medical Graphics.

The mechanism(s) by which platelet activation can either prevent or promote permeability of the vasculature is intriguing: (1) vasculature composition, (2) the different mediators present in situ, and (3) the platelet receptor(s) engaged may govern whether platelets play anti- or pro-permeability roles. Indeed, platelet-neutrophil and platelet-endothelial cell interactions are suggested to participate to leakage of vasculature in lungs and brain.37-39,50-52 In addition, the 13 different receptor subtypes for serotonin are capable of mediating distinct functions.53 Thus, the cell combination present in the vasculature and a unique pattern of expression of the various serotonin receptors might conceivably result in prevention versus promotion of vascular permeability. Further, the local concentrations of mediators, such as platelet-activating factor, sphingosine-1-phosphate, thromboxane A2, and prostacyclin, to name only a few, could influence platelet function and vascular leakage.37,50,54-61 Thromboxane A2 and prostacyclin in particular are counterbalancing mediators, the former stimulating platelet aggregation and the latter inhibiting it.58-60 Prostacyclin is present in mouse and human arthritic joints,62,63 and we have demonstrated that platelets produce prostacyclin with synoviocytes using a transcellular mechanism during arthritis.19,62,64 The balance between such mediators may thus impact platelet functions and guide the fate of the vasculature: its leakage or its preservation. Finally, arthritis is dependent on platelet GPVI activation and independent of GPIb.19 Platelets in the inflamed joint stimulated by this unique stimulus may sort particular granules, enriched with pro-permeability rather than anti-permeability factors. Indeed, the growing appreciation of platelet's capability to make available certain type of granule's mediators under different conditions is in agreement with this hypothesis.65,66

In conclusion, we revealed an unpredicted role for platelets in vasculature during inflammatory arthritis. Platelet serotonin coordinates the formation of gaps between endothelial cells in the joint microvasculature, of dimensions compatible with those of platelet MPs and immune complexes, and with their extrusion into the synovial space. The permeability created by the platelet-derived serotonin in the joint vasculature may thus contribute to the joint inflammation induced by MPs and to the joint-preference of arthritis disease mediated by immune complexes. In contrast to its accepted role in the maintenance of vascular integrity, the capacity of the platelet to contribute to permeability in vasculature, demonstrated here, adds to the rapidly growing list of unexpected functions for platelets.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Jasna Kriz (CRCHUQ, Université Laval) for the generous access to the Xenogen in vivo imaging system and Dr Denis Soulet (Assistant Professor, Département de Psychiatrie et Neurosciences de l'Université Laval) for his assistance with the cover image.

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Arthritis Society, the Canadian Arthritis Network, and the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec (all E.B.), the British Heart Foundation (R.W.F.), and the Cogan Family Foundation (P.A.N.).

Authorship

Contribution: N.C. conceived and designed the study, acquired, analyzed, and interpreted data, performed statistical analyses, and prepared the manuscript; A.P. and H.R.S. acquired, analyzed, and interpreted data and prepared the manuscript; R.W.F. generated critical reagents and prepared the manuscript; P.A.N. contributed critical reagents, analyzed and interpreted data, and prepared the manuscript; S.L. analyzed and interpreted data and prepared the manuscript; and E.B. conceived and designed the study, acquired, analyzed, and interpreted data, and prepared the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Eric Boilard, Centre de Recherche en Rhumatologie et Immunologie, Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier universitaire de Québec, 2705 Laurier Boulevard, Room T1-49, Québec, QC, G1V 4G2, Canada; e-mail: eric.boilard@crchuq.ulaval.ca.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal