Immune defect in ataxia telangiectasia patients has been attributed to either the failure of V(D)J recombination or class-switch recombination, and the chromosomal translocation in their lymphoma often involves the TCR gene. The ATM-deficient mouse exhibits fewer CD4 and CD8 single-positive T cells because of a failure to develop from the CD4+CD8+ double-positive phase to the single-positive phase. Although the occurrence of chromosome 14 translocations involving TCR-δ gene in ATM-deficient lymphomas suggests that these are early events in T-cell development, a thorough analysis focusing on early T-cell development has never been performed. Here we demonstrate that ATM-deficient mouse thymocytes are perturbed in passing through the β- or γδ-selection checkpoint, leading in part to the developmental failure of T cells. Detailed karyotype analysis using the in vitro thymocyte development system revealed that RAG-mediated TCR-α/δ locus breaks occur and are left unrepaired during the troublesome β- or γδ-selection checkpoints. By getting through these selection checkpoints, some of the clones with random or nonrandom chromosomal translocations involving TCR-α/δ locus are selected and accumulate. Thus, our study visualized the first step of multistep evolutions toward lymphomagenesis in ATM-deficient thymocytes associated with T-lymphopenia and immunodeficiency.

Introduction

Ataxia telangiectasia (AT) is an autosomal recessive disorder that is characterized by cerebellar ataxia, telangiectasia, immune defects, and a predisposition to malignancy, particularly leukemia/lymphoma.1,,–4 The immune defects observed in AT patients include fewer than normal T and B lymphocytes and lower serum IgA, IgG2, and IgE levels.5,6 The ATM knockout (ATM−/−) mouse has fewer CD4 and CD8 single-positive (SP) T cells because of a failure to develop from the CD4+CD8+ double-positive (DP) phase to the SP phase has been noted.7,–9

The responsible gene ATM works as a master regulator for maintaining DNA integrity and has crucial role for responding DNA double-strand break (DSB) from extrinsic and intrinsic factors, such as ionizing radiation, free oxygen radicals, unscheduled replicative stimuli, and DSB during V(D)J recombination.1,,–4,10 The role of ATM for V(D)J recombination of lymphocyte antigen receptor gene assembly or immunoglobulin synthesis is relatively well characterized. V(D)J recombination is initiated by the recombination activating genes (RAG)1 and RAG2 endonuclease. RAG protein binds and cleaves the DNA at specific recombination signal sequences (RSSs) that flank each V, D, and J gene segment.11 After cleavage, ATM and other DNA damage response proteins, such as NBS1, 53BP1, and phosphorylated H2AX localize to DSBs.12 Concurrently, classic nonhomologous end-joining complex is recruited.13 Recruitment of these molecules functions directly in the repair of chromosomal DNA DSBs by maintaining DNA ends in repair complexes. These processes promote correct resolution of inversional V(D)J recombination and prevent aberrant antigen receptor locus translocations.14 ATM deficiency leads to inefficient coding end binding after the RAG-dependent DSB generation at immunoglobulin and T-cell antigen receptor loci.15 Transition failure from DP to SP observed in ATM−/− mice has been explained because of decreased efficiency in V-J rearrangement of the T-cell receptor (Tcr) α locus, accompanied by increased frequency of unresolved TcrJα coding end breaks.8,9

Most of thymic lymphomas observed in ATM knockout mouse recapitulate these aspects of human AT and possess chromosome 14 translocations at the Tcrα/δ locus preferentially with chromosome 12 where mouse BCL11b gene located, and mostly express CD4+CD8+ phenotype.7,16 Interestingly, recent finding revealed that recurrent chromosome 14 translocations observed in ATM-deficient thymic lymphomas are associated with V(D)J recombination errors at Tcrδ, as opposed to Tcrα locus. In addition, Eα is completely dispensable for the oncogenic processes leading to these tumors.17

During T-cell development, early T-cell precursors differentiate first into CD4−CD8− double-negative (DN) and then to DP stages. CD4−CD8− DN T-cell subsets are further subdivided into DN1 to DN4 based on their expression of CD25 and CD117.18 Rearrangement of TCR-β, -γ, and -δ genes occurs mainly at the DN3 stage, although TCR-δ and -γ genes are thought to be partially rearranged at DN1 and DN2 stages. Successful rearrangement of TCR genes in DN3 cells drives their further differentiation. DN3 stage is subdivided into DN3a and DN3b depending on the successful TCR-β rearrangement, which is followed by the DN4 stage.19

It has been speculated that immunodeficiency and susceptibility to lymphoma in AT are the result of a defective TCR recombination and/or class switch recombination. Although the chromosome 14 translocations involving the breaks at TCR-δ locus in ATM-deficient T cells suggest these to be early events in T-cell development, in-depth analyses focusing on early T-cell development at DN phase has not been elucidated. Here we show that ATM-deficient thymocytes fail to progress from DN3a to DN3b, and chromosome 14 breaks and translocations involving TCR-α/δ locus concurrently occur during this transitional stage.

Methods

Mice

ATM+/− mice, originally on the129SvJ × C57BL/6 background, were a kind gift from Dr P. J. McKinnon (St Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN).20 The ATM+/− mice were backcrossed for more than 15 generations with C57BL/6 mice. ATM+/+ and ATM−/− mice were analyzed at 6 to 10 weeks of age. The Atm genotype was confirmed by PCR using tail DNA. RAG2−/− mice (BALB/c) and congenic CD45.1 mice (C57BL/6) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. The RAG2−/− mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice. To generate mice deficient for both RAG2 and ATM, RAG2−/− and ATM+/− mice were crossed and the progeny were typed by PCR. All of the mice were bred in the specific pathogen-free unit in the vivarium in Tokyo Medical and Dental University. Animal care was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol no. 0120228B). Sterile anti-CD3ϵ mAb (145-2C11) was injected intraperitoneally (150 μg/mouse).

Antibodies, flow cytometry, sorting, intracellular staining, and apoptosis analysis

Samples from thymi or cultured cells were stained using 5 or 6 antibody color combinations. The data were acquired on a FACSCalibur or FACSAria II (BD Biosciences) flow cytometry and analyzed using CellQuest Version 3.3 or FACSDIVA software. Each differential thymocyte phase was sorted by FACSAria II Version 6.1.3 (BD Biosciences) with more than 99% purity. The following antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences: anti–mouse CD3ϵ NA/LE, PE/Cy7 (145-2C11), CD25 PE, PE/Cy7 (PC61), CD27 PE (LG.3A10), CD44 APC (IM7), CD45 PE/Cy5, PE/Cy7 (30-F11), CD117 APC (2B8), γδ T-cell receptor PE (GL3), TCR-β chain FITC (H57-597), 7-amino-actinomycin D, annexin V, CD3 molecular complex FITC (17A2), CD4 FITC (RM4-5), CD8a FITC, PE (53-6.7), CD11b FITC (M1/70), TER-119 FITC (TER-119), Gr-1 FITC (RB6-8C5), CD19 FITC (1D3), B220 FITC (RA3-6B2), and NK1.1 FITC (PK136). The following antibodies were purchased from BioLegend: CD27 PerCP/Cy5.5 (LG.3A10), CD45.1 PE/Cy7 (A20), CD45.2 APC/Cy7, (104) CD117 APC/Cy7 (2B8), γδ T-cell receptor APC (GL3), TCR-β chain PerCP/Cy5.5, and APC-Cy7 (H57-597). The phospho-histone H2A.X (Ser139) Alexa-647 (20E3) antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling. The following were used as lineage markers: CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, B220, CD11b−, Gr1, NK1.1, and TER119. We measured intracellular TCR-β, TCR-γδ and pH2AX by flow cytometry using the IntraPrep Kit (Beckman Coulter). For apoptosis analysis, the cells were stained with the surface marker for 15 minutes, washed in 1% BSA containing PBS, and then stained with annexin V and 7-amino-actinomycin D in annexin V binding buffer according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences).

Cell-cycle analysis

We used Click-iT EdU flow cytometry assay kits for cell-cycle analysis (Invitrogen). The mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg of EdU in PBS. After 3 hours, single-cell suspensions were prepared from thymi and stained for cell surface markers. DN2, DN3a, DN3b, and DP stage thymocytes were all sorted by FACSAria II. The sorted cells were subjected to EdU detection according to the protocol of the manufacturer and analyzed with the FACSCalibur.

PCR detection for TCR-β V(D)J and DJ rearrangement

TCR gene rearrangement was analyzed as previously described.21 Genomic DNA was extracted from each thymocyte differentiation stage using a QIAamp DNA blood mini-kit (QIAGEN). The reaction volume was 25 μL and contained 10 ng of genomic DNA, 2.5 μL of 10× PCR buffer, 4 μL of 2.5mM dNTPs, 2.5 μL of 25μM MgCl2, 0.4μM of each primer, and 2.5 U of LA Taq polymerase (TaKaRa Biotechnology). The PCR reactions were performed as follows: 5 minutes at 95°C followed by 33 to 35 cycles of 30 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 60°C, and 2 minutes at 68°C, and a final extension for 7 minutes at 72°C with the GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems). The PCR products were analyzed on agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from DN2, DN3a, DN3b, DN4, and DP cells using an RNeasy kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was synthesized using Superscript III (Invitrogen) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green, and the reactions were monitored using a LightCycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics). The reactions were performed in duplicate at 95°C for 5 minutes for denaturation followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 seconds, 60°C for 10 seconds, and 72°C for 10 seconds. The primer sequences used are those described previously for pre–TCR-α,22 BCL11b,23 RAG1, and RAG2.24

Growth factors

Recombinant murine stem cell factor, recombinant murine FMS-like tyrosine kinase ligand (Flt3L), and rmIL-7 were purchased from R&D Systems.

Isolation of adult long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells

Single-cell suspensions of BM cells were prepared from 4- to 8-week-old mice. The cells were incubated with anti-Sca1 and anti-CD105 mAbs for 15 minutes on ice. Next, MACS magnetic beads were used for Sca1+ and CD105+ enrichment in a 2-step process according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Miltenyi Biotec).

In vitro differentiation of long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells

We cultured OP9-DLL1 cells in a 10-cm or 6-well plate with α-MEM medium containing 20% FBS, streptomycin (100 mg/mL), and penicillin (100 U/mL) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Approximately 1 to 3 × 104 long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells per well were cultured on semiconfluent OP9-DLL1 cells in medium containing 5 ng/mL of Flt3L and 1 ng/mL of IL-7. Floating cells were transferred to a fresh monolayer of semiconfluent OP9-DLL1 cells on days 6, 10, 14, and 18. For N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) experiments, the cells were incubated with 100μM or1mM NAC (Sigma-Aldrich). Singly sorted DN3a and DN3b cells from WT and ATM−/− thyme were cultured on OP9-DLL1 cells containing 5 ng/mL Flt3L and 1 ng/mL IL-7 in 96-well plates.

Bone marrow transplantation

Recipient mice (CD45.1) received myeloablative conditioning with 10 Gy of total body irradiation 6 hours before bone marrow transplantation (BMT). Bone marrow cells were harvested from donor mice (CD45.2) on the day of BMT and injected (1 × 107cells) into the tail vein of recipient mice. The mice received ad libitum drinking water containing 1 mg/mL neomycin trisulphate salt hydrate (Sigma-Aldrich) and 100 U/mL polymyxin B sulfate salt (Sigma-Aldrich).

FISH analysis of chromosome 12, chromosome 14, and the TCR-α/δ locus in DN phase thymocytes

To obtain DN2/DN3a cells, long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells were cultured on OP9-DLL1 cells in α-MEM containing 20% FBS, streptomycin (100 mg/mL), penicillin (100 U/mL), and 10 ng/mL of Flt3L, IL-7, and stem cell factor. To generate metaphase spreads, day 15 to 17 DN2/DN3a cells were treated with 25 ng/mL colcemid (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 hours. To collect DN3b/DN4 cells, we continued to cultivate differentiated DN2/DN3a cells in the same medium, but containing 5 ng/mL Flt3L and 1 ng/mL IL-7 for 7 to 10 additional days. After 25 ng/mL colcemid treatment for 2 hours, the DN3b/DN4 cells were sorted using a FACSAria II. DN2/DN3a cells and DN3b/DN4 cells were treated in hypotonic solution containing 0.06M potassium chloride and 0.02% sodium citrate solution for 20 minutes and then fixed in methanol and acetic acid. To perform FISH assays for the TCR-α/δ locus breaks, we used BAC probes for the 5′-end (RP23-204N18; 5′; blue) and 3′-end (RP23-10K20; green) of the TCR-α/δ locus. The BACs were labeled by amine-nick translation using the FISH Tag DNA multicolor kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). Chromosome 12 (green) and 14 (red) paint probes were purchased from Applied Spectral Imaging. The painting probes (10 μL) were mixed with 100 ng of 5′- and 3′-TCR α/δ locus probes and denatured at 80°C for 10 minutes before use. The slides were denatured at 67°C for 90 seconds and dehydrated in a cold ethanol series of 70%, 90%, and 100%. Hybridization was performed for 20 hours in a humidified chamber at 37°C. The slides were stringently washed in 0.4 × saline sodium citrate at 73°C for 4.5 minutes followed by 4 × saline sodium citrate/0.1% Tween-20 for 2 minutes and then mounted in SlowFade Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen) with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories). Images were captured with an FV10i confocal microscope (Olympus). Image acquisition and processing were performed using an Olympus FluoView Version 3.0 Viewer (Olympus).

Data analysis

Data are expressed as mean plus or minus SE. Unpaired t tests or ANOVA were used for statistical analysis. P values less than .05 were considered significant.

Results

Impaired development from DN3a to DN3b in ATM −/− thymus in vivo

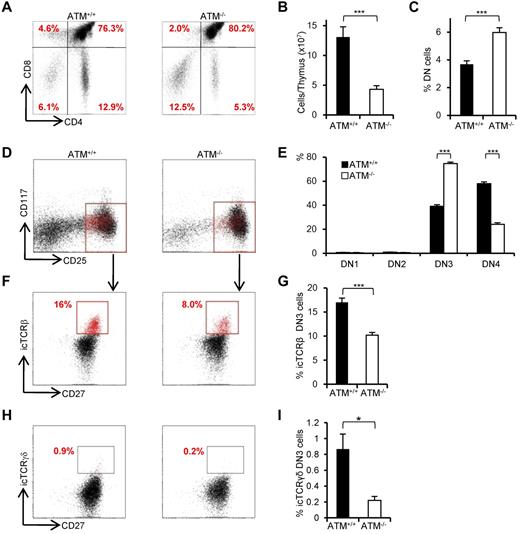

Consistent with previous reports,8,9 the proportion of CD4SP and CD8SP cells was decreased (Figure 1A) and total thymocyte numbers were significantly reduced in ATM−/− mice (Figure 1B). The relative percentage of cells in the DN phase was significantly higher in ATM−/− than in ATM+/+ mice (Figure 1C); and although the relative percentage of cells in DN1 and DN2 was slightly lower in total thymocytes of ATM knockout mice, there was an accumulation of cells in DN3 (Figure 1D-E). Interestingly, DN3b cells, which are characterized by the expression of CD27 and intracellular TCR-β or TCR-γδ, were significantly reduced in ATM−/− mice (Figure 1F-I). Collectively, these data indicate that ATM-deficient thymocytes fail to transit from the DN3a to the DN3b stage in both γδ T-cell and αβ T-cell lineages in vivo.

Developmental failure at the transition step from DN3a to DN3b in ATM−/− thymocytes. (A) Representative dot plots showing CD4 and CD8 profiles from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− mice. (B) Absolute numbers of total thymocytes in ATM+/+ and ATM−/− mice. (C) Relative percentage of lineage-negative cells. (D) Representative dot plots are gated on double-negative (DN) cells from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− mice, when DN3 cells reached at 1 × 104 cells. Red dots indicate DN3b cells that are back-gated from CD27+icTCR-β+ fraction. (E) Bar graph represents DN1, DN2, DN3, and DN4 thymocyte percentages. (F) Dot plots are gated on DN3 cells (CD25 low, indicated in red in the top panels). DN3a cells are shown as CD27low intracellular (ic) TCR-β−. DN3b cells are CD27highicTCR-β+ and are indicated as red dots in red squares. (G) Bar graph represents icTCR-β–positive DN3b thymocyte percentages in the DN3 fraction. (A-G) The data were obtained from 12 ATM+/+ mice and 11 ATM−/− mice at 4 to 8 weeks of age. (H) Dot plot data gated on DN3 cells from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− mice. The icTCR-γδ–positive cells, which are indicated as red dots in the black squares, are CD27+icTCR-γδ+. (I) Percentages of icTCR-γδ–positive DN3b thymocytes in the DN3 fraction. (H-I) Data were obtained from 6 ATM+/+ mice and 5 ATM−/− mice. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments (mean ± SE). *P < .05, ***P < .001.

Developmental failure at the transition step from DN3a to DN3b in ATM−/− thymocytes. (A) Representative dot plots showing CD4 and CD8 profiles from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− mice. (B) Absolute numbers of total thymocytes in ATM+/+ and ATM−/− mice. (C) Relative percentage of lineage-negative cells. (D) Representative dot plots are gated on double-negative (DN) cells from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− mice, when DN3 cells reached at 1 × 104 cells. Red dots indicate DN3b cells that are back-gated from CD27+icTCR-β+ fraction. (E) Bar graph represents DN1, DN2, DN3, and DN4 thymocyte percentages. (F) Dot plots are gated on DN3 cells (CD25 low, indicated in red in the top panels). DN3a cells are shown as CD27low intracellular (ic) TCR-β−. DN3b cells are CD27highicTCR-β+ and are indicated as red dots in red squares. (G) Bar graph represents icTCR-β–positive DN3b thymocyte percentages in the DN3 fraction. (A-G) The data were obtained from 12 ATM+/+ mice and 11 ATM−/− mice at 4 to 8 weeks of age. (H) Dot plot data gated on DN3 cells from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− mice. The icTCR-γδ–positive cells, which are indicated as red dots in the black squares, are CD27+icTCR-γδ+. (I) Percentages of icTCR-γδ–positive DN3b thymocytes in the DN3 fraction. (H-I) Data were obtained from 6 ATM+/+ mice and 5 ATM−/− mice. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments (mean ± SE). *P < .05, ***P < .001.

Transition failure from DN3a to DN3b of ATM−/− thymocyte in vitro

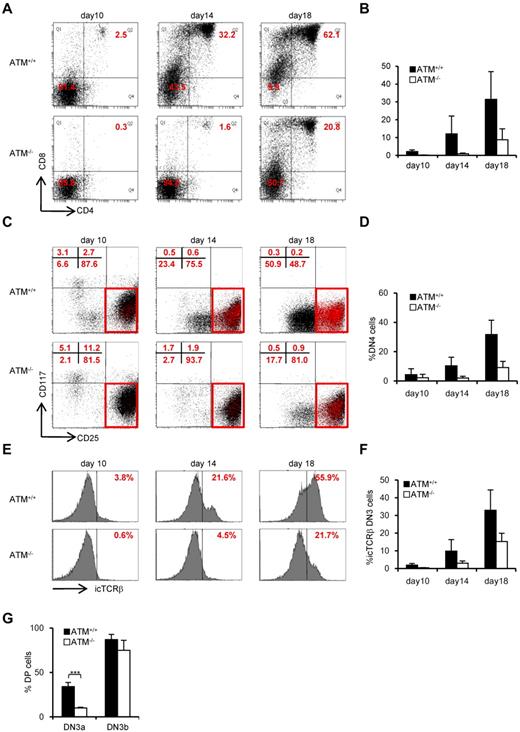

To further evaluate the failure in transition from DN3a to DN3b, we took advantage of an in vitro thymocyte development system. CD105+Sca-1+ BM cells, which represent a progenitor population containing hematopoietic stem cells (hereafter referred to as BM progenitors), from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− mice were cocultured on OP9-Delta like 1 (DLL1) cells with Flt3L and IL-7.25 DP cells began to appear on day 10 in ATM+/+ cell cultures and gradually accumulated. By contrast, DP cell production was not seen until day 14 in the ATM−/− cultures (Figure 2A-B). The DN phase profile gated on a lineage-negative fraction showed a failure in transition from DN3 to DN4 for the ATM−/− BM progenitors (Figure 2C-D). Analysis of intracellular (ic) TCR-β expression in the ATM−/− DN3 population allowed us to focus on the defect in the transition from the DN3a to the DN3b stage (Figure 2E-F). Neither T-cell development nor the transition from DN3a to DN3b in ATM−/− BM progenitors was restored by the treatment with 100μM or 1mM antioxidant NAC (supplemental Figures 1-3, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), ruling out the possibility that oxidative stress is involved in these processes, which was in contrast to the previous findings in the maintenance of HSCs and T-cell development.26,27 To directly demonstrate that the developmental failure of T cells in ATM−/− lies in the transition from DN3a to DN3b, singly sorted DN3a and DN3b cells of wild-type and knockout mice were cultured on OP9-DLL1 and analyzed for their potential to differentiate into DP cells. These clonal assays also confirmed that the DN3a stage cells fail to transit to DP cells in ATM−/− cells (10% ± 0.78% frequency) compared with ATM+/+ cells (34.2% ± 4.59% frequency). However, ATM−/− DN3b cells differentiated into DP cells as efficiently as the ATM+/+ cells (Figure 2G). Thus, the in vivo transitional failure from DN3a to DN3b was recapitulated in an in vitro system.

Transition failure from DN3a to DN3b is recapitulated in in vitro culture. Bone marrow progenitors (1 × 104 cells) from 4- to 8-week-old adult BM were cultured with OP9-DLL1 cells supplemented with 5 ng/mL of Flt3L and 1 ng/mL of IL-7 for 18 days. Differentiated cells were harvested on the indicated days. (A) Representative dot plots showing the surface expression of CD4 and CD8 (top) from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− BM progenitors. (B) Percentages of CD4+CD8+ DP phase cells at the indicated time points. (C) Dot plots are gated on DN phase from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− BM progenitors. Red squares represent DN3 cells. Representative dot plots are shown when DN3 cells reached 1 × 104 cells. Red dots indicate DN3b cells that are back-gated from the CD27+icTCR-β+ fraction. (D) Percentages of DN4 phase at the indicated time points. (E) Representative histograms showing expression of icTCR-β on DN3 cells. (F) Percentages of icTCR-β–positive cells on DN3 cells at the indicated time points. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Bar graphs represent mean ± SE. (G) Singly sorted DN3a and DN3b cells from each ATM+/+ and ATM−/− thymus were cultured on OP9-DLL1. Percentage of cells successfully differentiated to CD4+ and CD8+ (DP) phase were evaluated by flow cytometry on day 4. Bar graph represents mean percentage from 5 independent experiments. Data are mean ± SE. ***P < .001.

Transition failure from DN3a to DN3b is recapitulated in in vitro culture. Bone marrow progenitors (1 × 104 cells) from 4- to 8-week-old adult BM were cultured with OP9-DLL1 cells supplemented with 5 ng/mL of Flt3L and 1 ng/mL of IL-7 for 18 days. Differentiated cells were harvested on the indicated days. (A) Representative dot plots showing the surface expression of CD4 and CD8 (top) from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− BM progenitors. (B) Percentages of CD4+CD8+ DP phase cells at the indicated time points. (C) Dot plots are gated on DN phase from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− BM progenitors. Red squares represent DN3 cells. Representative dot plots are shown when DN3 cells reached 1 × 104 cells. Red dots indicate DN3b cells that are back-gated from the CD27+icTCR-β+ fraction. (D) Percentages of DN4 phase at the indicated time points. (E) Representative histograms showing expression of icTCR-β on DN3 cells. (F) Percentages of icTCR-β–positive cells on DN3 cells at the indicated time points. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Bar graphs represent mean ± SE. (G) Singly sorted DN3a and DN3b cells from each ATM+/+ and ATM−/− thymus were cultured on OP9-DLL1. Percentage of cells successfully differentiated to CD4+ and CD8+ (DP) phase were evaluated by flow cytometry on day 4. Bar graph represents mean percentage from 5 independent experiments. Data are mean ± SE. ***P < .001.

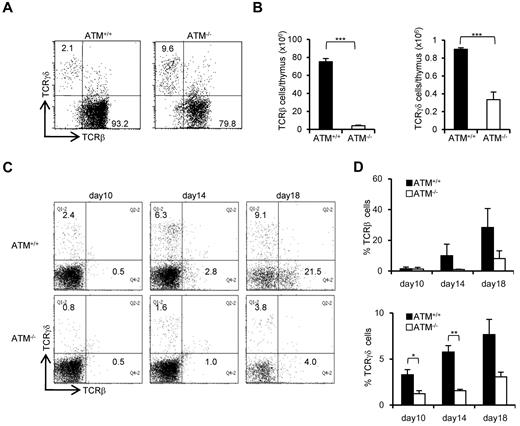

Inefficient TCR-γδ lineage differentiation in ATM−/− mice

The ratio of peripheral TCR-γδ to TCR-αβ T cells (TCR-γδ/TCR-αβ) in AT patients is reportedly relatively higher.28 Consistent with previous reports, the TCR-γδ cell population was relatively higher in ATM−/− mice thymus (Figure 3A). However, the absolute number of TCR-β and TCR-γδ–positive cells was significantly decreased in ATM−/− thymus than ATM+/+ thymus (Figure 3B). Then, in vitro T-cell differentiation system using BM progenitors was used to determine how cell surface TCR-β and γδ expression is deregulated in ATM−/− cells, as reflected by the delay or decrease in numbers of TCR-γδ and TCR-β T cells (Figure 3C-D). Possible involvement of reactive oxygen species was evaluated by NAC treatment, and NAC was shown not to improve the failure of TCR-β and TCR-γδ expression in ATM−/− thymocytes (supplemental Figure 4A-B). Thus, γδ-TCR lineage development is also affected in ATM−/− mice, but this was not reactive oxygen species dependent.

Both αβ and γδ T-cell developments are impaired in the ATM−/− thymus. (A) Dot plots for TCR-β and TCR-γδ expression gated on CD3-positive cells from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− thymi. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Absolute numbers of TCR-β (left) and TCR-γδ (right)–positive T cells from ATM+/+ (n = 4) and ATM−/− (n = 6) thymi. Data are mean ± SE. ***P < .001. (C) BM progenitors were cultured with OP9-DLL1 cells supplemented with 5 ng/mL of Flt3L and 1 ng/mL of IL-7 for 18 days. Differentiated cells were harvested on indicated days and stained for surface TCR-β and TCR-γδ. Dot plots are gated on CD45-positive cells from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− BM progenitors at the indicated time points. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Percentages of TCR-β and TCR-γδ-positive cells at the indicated time points. Data are mean ± SE. *P < .05. **P < .01.

Both αβ and γδ T-cell developments are impaired in the ATM−/− thymus. (A) Dot plots for TCR-β and TCR-γδ expression gated on CD3-positive cells from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− thymi. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Absolute numbers of TCR-β (left) and TCR-γδ (right)–positive T cells from ATM+/+ (n = 4) and ATM−/− (n = 6) thymi. Data are mean ± SE. ***P < .001. (C) BM progenitors were cultured with OP9-DLL1 cells supplemented with 5 ng/mL of Flt3L and 1 ng/mL of IL-7 for 18 days. Differentiated cells were harvested on indicated days and stained for surface TCR-β and TCR-γδ. Dot plots are gated on CD45-positive cells from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− BM progenitors at the indicated time points. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Percentages of TCR-β and TCR-γδ-positive cells at the indicated time points. Data are mean ± SE. *P < .05. **P < .01.

ATM is not involved in differentiation program from DN3 to DP

To confirm that the developmental program occurring from DN3b to DP stages is intact, we examined T-cell development in RAG2−/− mice. In both ATM+/+RAG2−/− and ATM−/−RAG2−/− mice, thymocytes accumulated equally at the DN3 stage, indicating that ATM has no effect on the development up to the β-selection checkpoint (supplemental Figure 5A), which is the gatekeeper for cells with a functional TCR-β chain. The developmental arrest at DN3 in RAG2−/− mice can be bypassed by stimulation of the pre-TCR complex (TCR-β/pTα/CD3) with anti-CD3ϵ antibody, allowing one to analyze the integrity of this signaling pathway in cell differentiation.29 By anti-CD3ϵ stimulation, thymocytes from ATM−/−RAG2−/− mice arrested at the DN3 stage differentiated into the DP stage as efficiently as those from ATM+/+RAG2−/− mice, and there was no difference in cell expansion efficiency (supplemental Figure 5B-C). We further examined the expression profiles of genes essential for early T-cell development, such as BCL11b, pTα, RAG1, and RAG2, in ATM−/− mouse thymocytes and found that they were normally expressed (supplemental Figure 6). These results indicate that the impaired development seen at the DN stage of ATM−/− thymocytes is not the result of the failure of the pre-TCR complex-dependent signaling pathway.

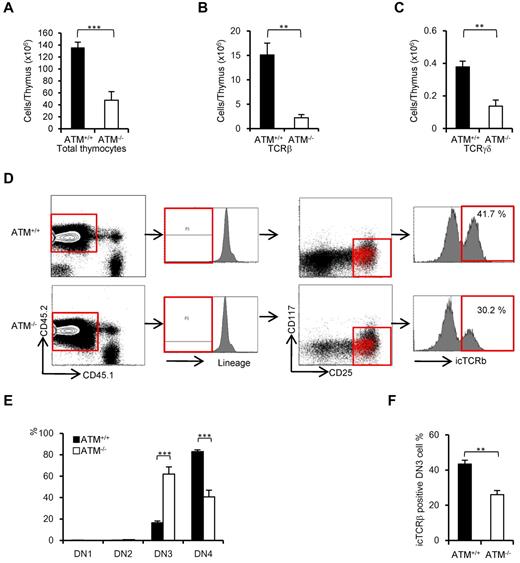

ATM-deficient thymic stroma supports normal transition from DN3a to DN3b

ATM-deficient thymic stromal cells reportedly do not affect the transition failure from DP to SP phase using BMT experiments.30 Recent reports have identified a role for the stromal cell derived factor 1α and its receptor CXC chemokine receptor 4 in β-selection.31,32 The functional role of ATM-deficient thymic stromal cells in β-selection of thymocytes has not been fully elucidated. To determine whether ATM-deficient thymic stromal cells affect thymocyte differentiation during DN phase, BM from ATM+/+ and ATM−/− C57/BL6 Ly5.2 donors was transplanted into lethally irradiated wild-type ATM+/+ C57/BL6 Ly5.1 recipients. Consistent with the result observed in ATM−/− mice, total thymocyte cellularity and absolute number of TCR-β and TCR-γδ T cells gated on CD45.2 were significantly reduced in the ATM−/− donor group (Figure 4A-C). ATM−/− thymocytes (CD45.2) in vivo reconstituted in the wild-type thymus also showed the transitional failure from DN3a to DN3b phase (Figure 4D-F). These findings of in vivo ATM−/− thymocyte differentiation in the thymic environment of ATM+/+ C57/BL6 Ly5.1 corresponded well to the findings in those cultured on OP9-DLL1 in vitro (Figure 2E-F). These results ruled out the possibility that differentiation defect of thymocytes at β-selection checkpoint is caused by thymic environment in the absence of ATM.

Thymic stromal cells of ATM−/− mice support DN3a to DN3b transition normally. Bone marrow cells from ATM+/+ or ATM−/− mice (Ly5.2) were transferred into lethally irradiated ATM+/+ mice (Ly5.1). The thymi were harvested from the reconstituted recipient ATM+/+ (Ly5.1) mice at 4 weeks after BMT. (A-C) Total thymocytes, TCR-β–positive cells, and TCR-γδ–positive cells were calculated on CD45.2-positive cells. For each group, more than 3 mice were analyzed. (D) Flow cytometric data from ATM+/+ thymocytes (Ly5.1) reconstituted with ATM+/+ or ATM−/− BM progenitors (Ly5.2). Cells were gated on CD45.2-positive and lineage-negative fractions and analyzed for CD25 and CD117 marker expression. Histograms show icTCR-β positivity in the DN3 phase. DN3b cells as defined by icTCR-β positivity were back-gated to the DN3 fraction and are indicated as red dots. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (E) Percentages of DN1, DN2, DN3, and DN4 cells in ATM+/+ (Ly5.1) recipient mice that received either ATM+/+ or ATM−/− BM progenitors (Ly5.2). Cells were gated on CD45.2 and analyzed. (F) Percentages of icTCR-β–positive DN3b thymocytes in the DN3 fraction in ATM+/+ (Ly5.1) recipient mice transplanted and gated as in panel E are shown. Data are mean ± SE. **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Thymic stromal cells of ATM−/− mice support DN3a to DN3b transition normally. Bone marrow cells from ATM+/+ or ATM−/− mice (Ly5.2) were transferred into lethally irradiated ATM+/+ mice (Ly5.1). The thymi were harvested from the reconstituted recipient ATM+/+ (Ly5.1) mice at 4 weeks after BMT. (A-C) Total thymocytes, TCR-β–positive cells, and TCR-γδ–positive cells were calculated on CD45.2-positive cells. For each group, more than 3 mice were analyzed. (D) Flow cytometric data from ATM+/+ thymocytes (Ly5.1) reconstituted with ATM+/+ or ATM−/− BM progenitors (Ly5.2). Cells were gated on CD45.2-positive and lineage-negative fractions and analyzed for CD25 and CD117 marker expression. Histograms show icTCR-β positivity in the DN3 phase. DN3b cells as defined by icTCR-β positivity were back-gated to the DN3 fraction and are indicated as red dots. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (E) Percentages of DN1, DN2, DN3, and DN4 cells in ATM+/+ (Ly5.1) recipient mice that received either ATM+/+ or ATM−/− BM progenitors (Ly5.2). Cells were gated on CD45.2 and analyzed. (F) Percentages of icTCR-β–positive DN3b thymocytes in the DN3 fraction in ATM+/+ (Ly5.1) recipient mice transplanted and gated as in panel E are shown. Data are mean ± SE. **P < .01, ***P < .001.

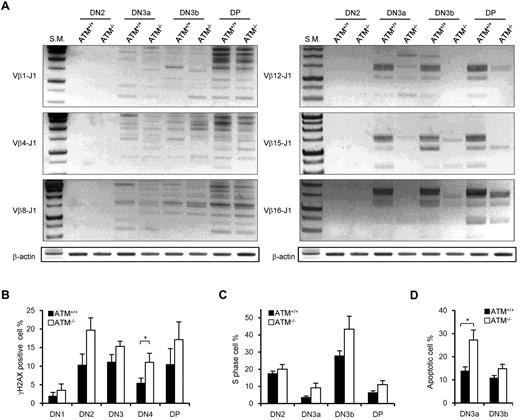

Nonequivalent TCR-β recombination and an increase in DNA DSBs in ATM−/− thymocytes

It has been shown that ATM+/+ and ATM−/− DN thymocytes have nearly equivalent levels of Jδ and Jβ1 signal end joining; however, there are reportedly higher levels of unrepaired Jβ1.1, Jβ1.2, and Jδ1 coding ends in ATM−/− mice.15 PCR analysis of TCR Dβ1-J1, Dβ2-J2, Vβ1-J1, Vβ4-J1, Vβ8-J1, Vβ1-J2, Vβ4-J2, and Vβ8-J2 recombination in DN2, DN3a, DN3b, and DP stage cells showed almost the same extent of polyclonal rearrangement in ATM+/+ and ATM−/− mice (Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 7A-B). However, the Vβ12-J1, Vβ15-J1, Vβ16-J1, Vβ12-J2, Vβ15-J2, and Vβ16-J2 rearrangements were relatively reduced in ATM−/− thymocytes (Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 7B), which is identical to that in thymocytes of mice engineered to express only the RAG2 core protein.33 Then, we speculated that DSBs at TCR-γ, -δ, and -β loci would remain unresolved in DN3a stage thymocytes of ATM−/− mice. Correspondingly, the frequency of γH2AX-positive cells, a marker for DSBs, was analyzed and shown to be higher in DN2 and DN3 and persist until DP in ATM−/− mice (Figure 5B).

Nonequivalent TCR-β recombination and an increase in DNA DSBs in ATM−/− thymocytes. (A) Rearrangement status of TCR Vβ1-Jβ1, Vβ4-Jβ1, Vβ8-Jβ1,Vβ12-Jβ1, Vβ15-Jβ1, and Vβ16-Jβ1 in the DN2, DN3a, DN3b, and DP stages was analyzed by PCR. (B) γH2AX-positive cell percentages in the DN1 to DP phases by flow cytometry. (C) Percentage of cells in S phase determined by flow cytometric analysis for PI and EdU incorporation at the DN2 to DP stages in ATM+/+ (n = 3)and ATM−/− thymocytes (n = 4). (D) Apoptotic cell percentages determined by flow cytometric analysis for annexin V positivity in the DN3a and DN3b stages. Data are mean ± SE. *P < .05.

Nonequivalent TCR-β recombination and an increase in DNA DSBs in ATM−/− thymocytes. (A) Rearrangement status of TCR Vβ1-Jβ1, Vβ4-Jβ1, Vβ8-Jβ1,Vβ12-Jβ1, Vβ15-Jβ1, and Vβ16-Jβ1 in the DN2, DN3a, DN3b, and DP stages was analyzed by PCR. (B) γH2AX-positive cell percentages in the DN1 to DP phases by flow cytometry. (C) Percentage of cells in S phase determined by flow cytometric analysis for PI and EdU incorporation at the DN2 to DP stages in ATM+/+ (n = 3)and ATM−/− thymocytes (n = 4). (D) Apoptotic cell percentages determined by flow cytometric analysis for annexin V positivity in the DN3a and DN3b stages. Data are mean ± SE. *P < .05.

ATM-deficient DN3a cells are defective in cell-cycle regulation and prone to apoptosis

The in vivo cell-cycle profile and level of apoptosis induction were also investigated. Stringent regulation of the timing of gene recombination is crucial for maintaining genomic integrity during normal lymphocyte development. RAG-mediated recombination is limited to the noncycling (G1) phase of the cell cycle; cells preferentially arrest at G1 and undergo RAG-mediated TCR-γ, -δ, or -β recombination in the DN3a stage. Cells that successfully achieved normal TCR-γ, -δ, or -β recombination resume cell-cycle progression toward DN3b. Another wave of transient cell-cycle arrest occurs in the early DP phase when the TCR-α locus begins to recombine. Although the cell-cycle profiles of thymocytes in ATM+/+ and ATM−/− were not significantly different from one another in the DN2 stage, more ATM−/− cells than ATM+/+ cells were observed to be cycling through DN3a into the DP phases (Figure 5C). Furthermore, apoptotic cells were significantly increased in DN3a cells from ATM−/− mice (Figure 5D), corresponding to the previous findings that thymocytes that fail to functionally rearrange the TCR-β chain undergo apoptosis.

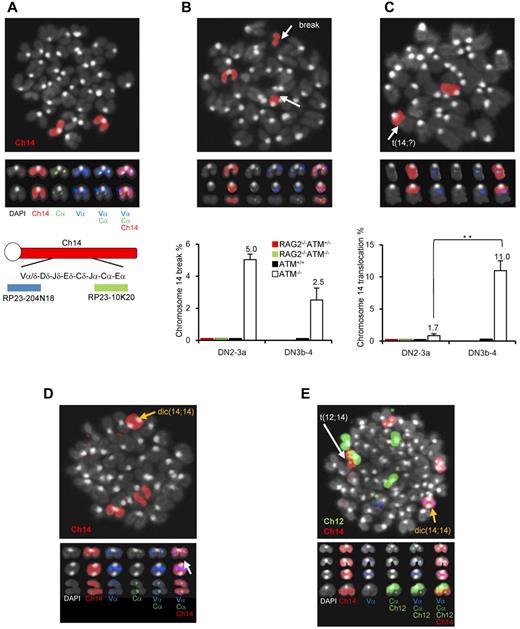

Chromosomal breaks at the TCR-α/δ locus and translocations in T-cell progenitors lacking ATM

ATM−/− lymphocytes and leukemia/lymphoma cells exhibit characteristic intralocus rearrangements involving either the TCR or IGH locus.17,34,–36 Chromosomal translocations with gene amplification involving the TCR-α/δ locus were also observed in ATM-deficient mice.17,37 Based on our findings, we hypothesized that the DN3a to DN3b transition, which is defective in ATM−/− thymocytes, is the window with the highest risk for the formation of chromosome 14 translocations involving TCR-α/δ locus breaks. To monitor chromosome 14 integrity before and after the DN3a phase, an in vitro coculture system, which has been developed by modifying a previously reported system,38 combined with FISH analysis was performed (supplemental Figure 8). Normal chromosome 14, as shown in red, contains colocalized blue and green foci corresponding to the 5′- and 3′-end of the TCR-α/δ loci, respectively (Figure 6A). Chromosome 14 breaks at the TCR-α/δ locus were observed in 5% of ATM−/− DN2/DN3a cells (54 of 1073 metaphase cells) and 2.5% of ATM−/− DN3b/DN4 cells (11 of 437 metaphase cells; Figure 6B; supplemental Tables 1 and 2), but none in the ATM+/+, ATM+/−RAG2−/−, or ATM−/−RAG2−/− cells, indicating that these breaks in ATM−/− thymocytes are RAG-dependent. Chromosome 14 translocations involving the TCR-α/δ locus were occasionally detected in ATM−/− DN2/DN3a cells (1.77%; 19 of 1073 metaphase cells), but not in ATM+/+ (961 metaphase cells), ATM+/−RAG2−/− (985 metaphase cells), or ATM−/−RAG2−/− cells (1034 metaphase cells). Interestingly, the frequency of these chromosomal translocations dramatically increased during the progression to DN3b/DN4 in ATM−/− cell (11.4%; 50 of 437 metaphase cells; Figure 6C; supplemental Tables 1-2). These results suggest that chromosome 14 translocations involving TCR-α/δ locus are mainly generated during DN3a to DN3b transitional stage.

Chromosomal breaks at the TCR-αδ locus and translocations in T-cell progenitors lacking ATM. (A) Normal karyotype; FISH probe hybridized with 5′-TCR-α/δ (blue) and 3′-TCR-α/δ (green). Red represents the chromosomal paint probe for mouse chromosome 14. E indicates defined transcriptional enhancer elements. (B) Representative images of breaks between 5′TCR-α/δ (blue) and 3′TCR-α/δ (green) on chromosome 14 (red; top panel). The percentage of DN2/DN3a cells and DN3b-DN4 cells with a TCR-α/δ locus break is shown in a bar graph (bottom panel). Thymocyte maturation arrests at the DN2/DN3a stage in RAG2−/− mice; thus, DN3b-DN4 phase locus breaks cannot be measured. (C) Representative images of a chromosomal translocations (top panel). The percentage of cells with a chromosome 14 translocations is shown in a bar graph (bottom panel). y-axis indicates change to percentage chromosome 14 breaks and translocations. (D) Representative images of chromosomal abnormalities showing the TCR-α/δ locus on a dicentric chromosome 14 (yellow arrow) and breaks (white arrow). (E) Representative image of a chromosomal 12;14 translocation (white arrow) and a dicentric chromosome 14 (yellow arrow). Data are mean ± SE. **P < .01.

Chromosomal breaks at the TCR-αδ locus and translocations in T-cell progenitors lacking ATM. (A) Normal karyotype; FISH probe hybridized with 5′-TCR-α/δ (blue) and 3′-TCR-α/δ (green). Red represents the chromosomal paint probe for mouse chromosome 14. E indicates defined transcriptional enhancer elements. (B) Representative images of breaks between 5′TCR-α/δ (blue) and 3′TCR-α/δ (green) on chromosome 14 (red; top panel). The percentage of DN2/DN3a cells and DN3b-DN4 cells with a TCR-α/δ locus break is shown in a bar graph (bottom panel). Thymocyte maturation arrests at the DN2/DN3a stage in RAG2−/− mice; thus, DN3b-DN4 phase locus breaks cannot be measured. (C) Representative images of a chromosomal translocations (top panel). The percentage of cells with a chromosome 14 translocations is shown in a bar graph (bottom panel). y-axis indicates change to percentage chromosome 14 breaks and translocations. (D) Representative images of chromosomal abnormalities showing the TCR-α/δ locus on a dicentric chromosome 14 (yellow arrow) and breaks (white arrow). (E) Representative image of a chromosomal 12;14 translocation (white arrow) and a dicentric chromosome 14 (yellow arrow). Data are mean ± SE. **P < .01.

Interestingly, some of the dicentric chromosome 14s carried amplification upstream of the TCRV-α locus (Figure 6D-E), an abnormality that is frequently observed in ATM−/− thymic lymphoma cells (supplemental Figure 9). In this culture system, the other characteristic abnormalities, including aneuploidy, were also identified during the DN2/DN3a and DN3b/DN4 stages (Figure 6D-E; supplemental Table 3). Sister chromatid breaks in chromosome 12 during mitotic phase and subsequent t(12;14) translocations were also observed in a minor fraction of cells at the DN2/DN3a and DN3b/DN4 stages (Figure 6E; supplemental Figure 10). Chromosome 12, which contains the IGH and BCL11b loci, is often a reciprocal chromosome 14 translocation partner in ATM-deficient thymic lymphoma.

Discussion

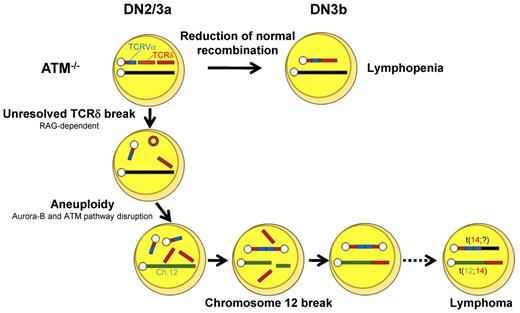

In this study, we have visualized, for the first time, the critical developmental step of TCR-α/δ chromosomal breaks and translocations in ATM-deficient thymocytes and narrowed down the DN3a to DN3b stages to be the window for these events.

DN phase differentiation failure in ATM-deficient thymocytes has been speculated to be the result of faulty V(D)J recombination by in vitro studies.14 Transition failure from DP to SP phase was also reported in in vivo thymus.8,9 However, accurate profiles for T-cell development at DN phase have not been elucidated in ATM-deficient thymocytes. In addition, some other possibilities need to be ruled out that ATM-deficient thymic stromal cell has negative effect for DN phase development, and ATM itself has roles for a differentiation program, such as transcription factor and signal mediator. We find that DN3a and DN3b differentiation failure is only the result of TCR recombination failure, but not defective thymic stromal cells or aberrant differentiation program in ATM-deficient thymocytes. In the absence of ATM, DN2/DN3a thymocytes were demonstrated to be defective in TCR-γδ and TCR-β recombination, as evidenced by a failure of intracellular TCR-γδ and β expression. They were defective in differentiation toward both αβ and γδ-T-cell lineage in vitro, and absolute numbers of αβ and γδ T cells were decreased in ATM−/− thymus. These findings suggest that T-lymphopenia in ATM-deficient mice is caused by differentiation failure of thymocytes at the early stage from DN3a to DN3b before the stage from DP to SP by defective resolution of TCR breaks.

We demonstrated that the recombinations of TCR Vβ12, Vβ15, and Vβ16-DJ were not successful in ATM−/− thymocytes compared with those of Vβ1, Vβ4, and Vβ8-DJ (Figure 5A). This skewed pattern of TCR-β recombination is identical to that in thymocytes of mice engineered to express only the RAG2 core protein (Rag2c/c; ie, the portion of the molecule that, together with core RAG1, is the minimal region required for in vitro V(D)J recombination). RAG2c/c mice show inefficient recombination for Vβ10, Vβ11, Vβ12, and Vβ15 compared with Vb2 and Vb8 because of a different RSS spacer sequence in these groups.33 Our findings and these observations seen in the Rag2c/c mouse suggest that ATM and RAG protein might interact or ATM may modify RAG function by phosphorylation or not during recognition of specific RSS sequence for V(D)J recombination. Furthermore, Rag2c/cp53−/− mice exhibit similar phenotype with ATM-deficient DN profiles and rapidly develop lymphoma with chromosome translocations at the TCR-δ locus.37 The defects of T-cell development in these engineered mice are mainly the result of the loss of interaction between the RAG postcleavage complex with ATM and is compatible with our observation in ATM−/− thymocytes.

RAG1 is expressed throughout the cell cycle, whereas RAG2 is periodically destructed at the G1-to-S transition and is stable only during G0 or G1 phase, which limits V(D)J recombination to occur only at G0 and G1 cell-cycle phases. Thus, coordinated RAG expression and organized cell-cycle checkpoint are indispensable to prevent aberrant chromosome translocation.11,39 Cell-cycle deregulation to enter S-phase was observed in phases through DN2 to DP in ATM−/− thymocytes. Thus, it is probable that the G1-S checkpoint failed to be activated in ATM−/− thymocytes possibly involving or not the failure of Pim2 kinase expression that is mediated by ATM.40 In our analysis, it was also noted that apoptotic cells were significantly increased in DN3a in ATM−/− thymocytes. Together, these findings unresolved coding end joining concomitant with disorganized cell-cycle checkpoint regulation as well as increased DNA breaks associated with apoptotic nuclear events might lead to genomic instability in early developmental stages of T cells in ATM−/− mice.41,42

Our findings led us to propose the following model for the process of generation of chromosome breaks and translocations in ATM deficiency. During DN2/DN3a, RAG-mediated breaks are generated, and they persist beyond the G1 phase because of defective TCR-β V-DJ recombination and cell-cycle progression. These cells are detected as those carrying chromosomal breaks at TCR-δ on chromosome 14 (Figure 6B). After the DN3b stage, some of these chromosomes recombine with unknown partner chromosomes or occasionally with an inappropriately replicated chromosome 14 itself, leading to dicentric chromosome formation. Occasionally, the upstream TCRV-α locus is amplified by multiple cycles of this process (Figure 6D-E). These findings are reflected by those that aurora-B mediated mitotic ATM activation and the spindle checkpoint play essential roles to suppress aneuploidy.43 Genomic instability associated with ATM deficiency may also generate chromatid breaks, including chromosome 12, which were observed in minor fraction compared with RAG-dependent chromosome 14 breaks (supplemental Figure 10). Chromosome 12 is a well-known partner of chromosome 14 translocation in ATM−/− thymic lymphoma. The break sites on chromosome 12 are widely spread on 30-Mb-long from IGH locus to centromeric portion involving BCL11b and TCL1 loci, not always involving cryptic RSS,17 and breaks were detected as chromatid breaks, not as bilateral chromosomal breaks. Taken together, these findings suggest that chromosome 12 breaks presumably occur in RAG-independent manner after completion of sister chromatid synthesis.

These processes, be they random or nonrandom, may lead to chromosome translocations, some of which may somehow get through the checkpoints by successful TCR-γδ or TCR-β recombination and lead to the development of phenotypically normal lymphocytes, yet carrying over oncogenic potentials, after the DN3b/DN4 stages. Loss of genomic guardian systems, such as the ATM-p53 pathway, may enhance additional steps for tumorigenesis.44 Together with these findings, the initial step of multistep evolutions toward lymphomagenesis was visualized in ATM-deficient thymocytes. RAG-dependent failure during TCR recombination and RAG-independent disruption of chromosomal architecture may be intimately involved in the process for tumor formation.

In conclusion, T-cell developmental failure leading to immunodeficiency and chromosomal translocations involving the TCR-α/δ locus derive from mutually integrated events during the DN2/DN3a stages in ATM-deficient T cells (Figure 7). We propose that our in vitro experimental method is also useful for the functional validation of mutation-targeted therapeutic technologies for AT patients in the future.45 In light of the finding that 35% of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias carry chromosomal translocations involving TCR genes,46 our findings also suggest that epigenetic dysregulation of ATM or posttranscriptional deregulation of ATM gene might be involved in the formation of chromosomal translocations involving TCR genes in some T-cell leukemias with an apparently normal ATM gene.

Model for thymocyte development lacking ATM. Schematic illustration for the impaired thymocyte development and creation of a translocation involving the TCR locus.

Model for thymocyte development lacking ATM. Schematic illustration for the impaired thymocyte development and creation of a translocation involving the TCR locus.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank P. J. McKinnon for providing ATM+/− mice; M. F. Greaves, P. D. Burrows, and K. Enomoto for critical reading for manuscript; and Y. Kutami for technical support.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture (Japan) and Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (Japan; M.T. and S.M.).

Authorship

Contribution: T. Isoda, M.T., T.M., H.K., and S.M. conceived the study and wrote the paper; and T. Isoda, J.P., S.N., M.S., K.M., T. Ikawa, and M.A. designed and performed experiments.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Masatoshi Takagi and Shuki Mizutani, Department of Paediatrics and Developmental Biology, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, 1-5-45 Bunkyo-ku, Yushima, Tokyo 113-8519, Japan; e-mail: m.takagi.ped@tmd.ac.jp or smizutani.ped@tmd.ac.jp.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal