Abstract

To understand more specific abnormalities of humoral autoimmunity, we studied 31 spleens from immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) patients and 36 control spleens. Detailed analysis identified at least 2 different splenic structures accommodating proliferating B cells, classic germinal centers (GCs), and proliferative lymphoid nodules (PLNs). PLNs were characterized by proliferating Ki67+ B cells close to follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) and lacked polarization into dark and light zones. As opposed to cells in GCs, proliferating B cells in PLN lacked expression of Bcl6. In both PLNs and GCs of ITP spleens, the density of T cells was significantly reduced. Both T follicular helper cells (TFH) and regulatory T cells were reduced within PLNs of ITP spleens suggesting a defect of tolerance related to a loss of T-cell control. Within PLNs of ITP, but not controls, abundant platelet glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa autoantigens was found in IgM containing immune complexes tightly bound to FDCs and closely approximated to proliferating B cells. GPIV was found less often, but not in the same PLNs as GPIIb/IIIa. Autoantigens were not found in the GCs of ITP or controls indicating that PLNs are the sites of autoantigen stimulation in ITP potentially related to a lack of control by T cells and/or the present autoantigen.

Introduction

Autoimmunity arises when there is a breakdown of tolerance and the development of antibody (Ab) production directed to self-antigens (Ag). Many putative mechanisms have been suggested to explain the loss of tolerance, including abnormalities in B-cell responses, increases in the function of T follicular helper cells (TFH), reduced number of regulatory T cells (Tregs), abnormal cytokine or chemokine production, and exaggerated Th1 responses, as well as stimulation by exogenous factors that signal through Toll-like receptors (TLRs).1,2 Despite this wealth of information, the fundamental factors controlling the emergence of autoimmunity remain unknown. Moreover, whether autoimmunity arises in T cell–dependent germinal centers3 (GCs), T cell–dependent or –independent extrafollicular responses,4,5 or as a result of TLR costimulation during T cell–independent responses6 remains to be fully delineated.

In humans, antibody production has largely been studied in vitro, ex vivo in available secondary lymphoid tissue, such as tonsil, or after transfer of human cells or tissue into immunodeficient mice. Each of these studies has implicit shortcomings and has not yielded unambiguous data about the control of autoantibody production. Secondary lymphoid tissues, such as spleen, have not frequently been studied because of the difficulty of obtaining them reliably. It is clear, however, that the structure of human spleen is considerably different from the murine counterpart,7 making it essential to gain more information about the nature of the human splenic architecture so as to interpret the relevance of murine experiments, and fully understand the origin of human autoimmunity.

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP)8 is a human autoimmune disease in which autoantibodies mediate the opsonization, loss of platelets from the circulation,9 and abnormalities of T helper cells10-12 and Tregs.13 The most common autoantibodies in ITP serum target the platelet glycoproteins (GP) GPllb/llla, GPIb/lX, and to a lesser extent GPIV and GPla/lla.14 These autoantibodies are directed to Ag on the platelet surface and lead to increased destruction of circulating platelets, resulting in thrombocytopenia and possibly hemorrhagic complications. Because subjects with ITP refractory to standard therapy may require splenectomy,15 samples of spleen tissues are available for study. Importantly, it is thought that the autoimmune response to platelet antigens arises in the spleen,11 making study of this tissue ideal to determine the nature of the immune response that underlies this autoimmune disease.

The current study investigated 67 human spleens and analyzed their splenic B-cell structures. Nonpolarized aggregates of proliferating B cells distinct from classic GCs were identified in both ITP and normal spleens, but in ITP spleens platelet autoantigen immune complex (IC) bound to FDCs were frequently observed in these structures suggesting that they are sites of autoantigenic stimulation.

Methods

A detailed description of spleen specimens and methods is available as supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Patients and patient samples

A collection of 31 splenic specimens from patients (42.4 ± 17.8 years old) with ITP requiring splenectomy and 36 splenic specimens obtained from subjects undergoing splenectomy because of trauma (42.0 ± 18.9 years old) were analyzed in this study. The patients' characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The study has been approved by the institutional review board at Charité University Hospitals (Berlin, Germany) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Demographic of ITP and control patients

| Variable . | ITP patients, n = 31 . | Control, n = 36 . |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 42.4 (17.8) | 42.0 (18.9) |

| Infections | 3 | 2 |

| Cancer | None | 3 |

| Autoimmune diseases | 6 | 0 |

| Variable . | ITP patients, n = 31 . | Control, n = 36 . |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 42.4 (17.8) | 42.0 (18.9) |

| Infections | 3 | 2 |

| Cancer | None | 3 |

| Autoimmune diseases | 6 | 0 |

ITP indicates immune thrombocytopenia.

Characteristics of the ITP patients enrolled in the study

| Age, y . | Duration of disease, y . | Associated diseases . | Treatment before splenectomy . | Platelet count before (after) splenectomy, 109/mL . | Infection upon splenectomy . | Absolute number of lymphoid nodules (GCs)/3.7 cm2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 19 | Evans syndrome | IvIg, MMF, Prednisol | 2 (22) | None | 42 (0) |

| 64 | 2 | None | Prednisol, azathioiprine, IvIg | 17 (204) | None | 112 (1) |

| 56 | < 1 | Autoimmunodermatitis | Prednisol, IvIg, HC | 21 (110) | None | 46 (0) |

| 77 | < 1 | Colitis ulcerosa | Prednisol, MMF | 29 (443) | Staphylococcal aureus sepsis | 31 (0) |

| 65 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 44 (0) |

| 39 | 20 | None | Prednisol, IvIg | 18 (123) | NA | 48 (8) |

| 43 | 8 | None | IvIg, MMF | 3 (410) | S aureus sepsis | 63 (0) |

| 27 | < 1 | Autoimmune thyroidtis | Prednisol, IvIg | 15 (617) | None | 59 (0) |

| 70 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 45 (0) |

| 49 | 1 | None | Prednisol, IvIg | 10 (512) | None | 37 (0) |

| 38 | 3 | Evans syndrome | Prednisol | 12 (170) | None | 41 (1) |

| 23 | < 1 | None | Prednisol | 4 (54) | NA | 63 (1) |

| 27 | < 1 | None | Prednisol | 25 (133) | None | 59 (27) |

| 27 | < 1 | None | Prednisol, IvIg | 52 (212) | None | 112 (38) |

| 41 | 13 | Evans syndrome | Prednisol | 13 (78) | None | 43 (0) |

| 44 | < 1 | None | NA | NA | HIV | 33 (1) |

| 39 | 4 | None | Prednisol | 10 (208) | NA | 45 (8) |

| 22 | < 1 | None | Prednisol, IvIg | 11 (74) | None | 38 (0) |

| 24 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 26 (0) |

| 18 | < 1 | None | Prednisol | 11 (60) | None | 73 (2) |

| 26 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 52 (0) |

| 68 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 61 (0) |

| 53 | < 1 | None | Prednisol, vincristin | 2 (500) | None | 57 (0) |

| 69 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 54 (2) |

| 31 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 64 (16) |

| 22 | 1 | None | Prednisol, IvIg, vincristin azathioprine | 5 (636) | None | 72 (18) |

| 43 | 25 | None | IvIg, anti-D, azathioprine, platelet transfusion | NA (164) | Recurrent infections | NA |

| 71 | 7 | Multiple sclerosis | Mycophenolate, prednisol | < 10 (191) | None | NA |

| 52 | 1 | None | IvIg, anti-D, platelet transfusion | NA (< 10) | None | NA |

| 32 | 3 | None | IvIg, Prednisol, anti-D | NA (320) | None | NA |

| 24 | 2 | None | IvIg, Prednisolone, anti-D, dexamethasone, azathioprine | NA (295) | None | NA |

| Age, y . | Duration of disease, y . | Associated diseases . | Treatment before splenectomy . | Platelet count before (after) splenectomy, 109/mL . | Infection upon splenectomy . | Absolute number of lymphoid nodules (GCs)/3.7 cm2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 19 | Evans syndrome | IvIg, MMF, Prednisol | 2 (22) | None | 42 (0) |

| 64 | 2 | None | Prednisol, azathioiprine, IvIg | 17 (204) | None | 112 (1) |

| 56 | < 1 | Autoimmunodermatitis | Prednisol, IvIg, HC | 21 (110) | None | 46 (0) |

| 77 | < 1 | Colitis ulcerosa | Prednisol, MMF | 29 (443) | Staphylococcal aureus sepsis | 31 (0) |

| 65 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 44 (0) |

| 39 | 20 | None | Prednisol, IvIg | 18 (123) | NA | 48 (8) |

| 43 | 8 | None | IvIg, MMF | 3 (410) | S aureus sepsis | 63 (0) |

| 27 | < 1 | Autoimmune thyroidtis | Prednisol, IvIg | 15 (617) | None | 59 (0) |

| 70 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 45 (0) |

| 49 | 1 | None | Prednisol, IvIg | 10 (512) | None | 37 (0) |

| 38 | 3 | Evans syndrome | Prednisol | 12 (170) | None | 41 (1) |

| 23 | < 1 | None | Prednisol | 4 (54) | NA | 63 (1) |

| 27 | < 1 | None | Prednisol | 25 (133) | None | 59 (27) |

| 27 | < 1 | None | Prednisol, IvIg | 52 (212) | None | 112 (38) |

| 41 | 13 | Evans syndrome | Prednisol | 13 (78) | None | 43 (0) |

| 44 | < 1 | None | NA | NA | HIV | 33 (1) |

| 39 | 4 | None | Prednisol | 10 (208) | NA | 45 (8) |

| 22 | < 1 | None | Prednisol, IvIg | 11 (74) | None | 38 (0) |

| 24 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 26 (0) |

| 18 | < 1 | None | Prednisol | 11 (60) | None | 73 (2) |

| 26 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 52 (0) |

| 68 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 61 (0) |

| 53 | < 1 | None | Prednisol, vincristin | 2 (500) | None | 57 (0) |

| 69 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 54 (2) |

| 31 | < 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 64 (16) |

| 22 | 1 | None | Prednisol, IvIg, vincristin azathioprine | 5 (636) | None | 72 (18) |

| 43 | 25 | None | IvIg, anti-D, azathioprine, platelet transfusion | NA (164) | Recurrent infections | NA |

| 71 | 7 | Multiple sclerosis | Mycophenolate, prednisol | < 10 (191) | None | NA |

| 52 | 1 | None | IvIg, anti-D, platelet transfusion | NA (< 10) | None | NA |

| 32 | 3 | None | IvIg, Prednisol, anti-D | NA (320) | None | NA |

| 24 | 2 | None | IvIg, Prednisolone, anti-D, dexamethasone, azathioprine | NA (295) | None | NA |

ITP indicates immune thrombocytopenia; GC, germinal center; NA, not available; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; HC, healthy control; and prednisol, prednisolon.

Quantification of GCs in spleen sections

All paraffin-embedded spleen biopsies were stained routinely with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and the numbers of total lymphoid nodules in the white pulp, including GCs and other proliferative B-cell nodules were enumerated using an Olympus BX70 microscope (magnification ×50).

Immunohistochemical staining of paraffin-embedded spleen sections

To analyze the difference between GCs and PLNs, serial paraffin-embedded sections from control spleens and ITP spleens were stained with anti-CD23 monoclonal Ab (mAb; 1B12; Novocastra Laboratories Ltd), anti-CD21 mAb (1F8; DAKO Deutschland GmbH), anti-Bcl6 mAb (PG-B6p; DAKO Deutschland GmbH), anti-Ki67 mAb (MiB-1; DAKO Deutschland GmbH), anti-GPIV (3H1265; LifeSpan BioSciences), and anti-IgM polyclonal Ab (pAb; DAKO Deutschland GmbH). For further analyses, splenic sections from 6 controls and 6 ITP patients were stained with anti–PD-1 mAb (192106; R&D Systems GmbH) and anti-CD3 mAb (F7.2.38; DAKO Deutschland GmbH). Finally, splenic sections from 3 controls and 3 ITP patients were stained with anti-Foxp3 mAb (PCH101; eBioscience). Details of the staining antibodies used for immunohistochemistry are summarized in Table 3.

Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry in paraffin sections

| Antibody . | Targets . | Dilution . | Antigen retrieval treatment . | Detection System from DAKO . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti–PD-1 | TFH cells | 1:5 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 2 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6 | Strept. AP system |

| Anti-CD3 | T cells | 1:100 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 2 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6 | APAAP system |

| Anti-CD21 | FDCs and MZ analog B cells | 1:50 | 20 minutes with Pronase at 37°C | APAAP system |

| Anti-BCl6 | TFH cells and GC B cells | 1:50 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 5 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6 | Strept. AP system |

| Anti-Ki67 | Proliferating cells | 1:2000 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 2 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6 | APAAP system |

| Anti-CD23 | FDCs and MZ analog B cells | 1:20 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 2 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6 | APAAP system |

| Anti-IgM | Plasma cells and B cells i | 1:1000 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 5 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6 | Strept. AP system |

| Anti-GPIV | Platelet glycoprotein IV: a target of autoantibody in ITP patients. | 1:200 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 1 minute in EDTA | Strept. AP system |

| Anti-Foxp3 | T(reg) | 1:50 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 2 minutes in sodium citrate buffer pH6 and 10 minutes 3% H2O2 blocking for endogenic peroxidase | EnVision+ System |

| Antibody . | Targets . | Dilution . | Antigen retrieval treatment . | Detection System from DAKO . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti–PD-1 | TFH cells | 1:5 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 2 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6 | Strept. AP system |

| Anti-CD3 | T cells | 1:100 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 2 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6 | APAAP system |

| Anti-CD21 | FDCs and MZ analog B cells | 1:50 | 20 minutes with Pronase at 37°C | APAAP system |

| Anti-BCl6 | TFH cells and GC B cells | 1:50 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 5 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6 | Strept. AP system |

| Anti-Ki67 | Proliferating cells | 1:2000 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 2 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6 | APAAP system |

| Anti-CD23 | FDCs and MZ analog B cells | 1:20 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 2 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6 | APAAP system |

| Anti-IgM | Plasma cells and B cells i | 1:1000 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 5 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6 | Strept. AP system |

| Anti-GPIV | Platelet glycoprotein IV: a target of autoantibody in ITP patients. | 1:200 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 1 minute in EDTA | Strept. AP system |

| Anti-Foxp3 | T(reg) | 1:50 | Heated in high-pressure cooker for 2 minutes in sodium citrate buffer pH6 and 10 minutes 3% H2O2 blocking for endogenic peroxidase | EnVision+ System |

TFH indicates T follicular helper; FDC, follicular dendritic cell; MZ, marginal zone; GC, germinal center; and ITP, immune thrombocytopenia.

Quantification of cells in splenic lymphoid nodules

Quantification of Ki67+, CD3+, PD-1+, and Foxp3+ cells was performed as follows: ITP and control spleen sections were stained with anti-Ki67, anti-CD3, anti-Foxp3, or anti–PD-1 Abs. All slides were screened using the Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 (×200 magnification; Carl Zeiss).

Immunofluorescence staining of frozen spleen samples

To identify B-cell subsets and FDCs, 3 frozen splenic tissue specimens from patients with ITP were stained and analyzed using dual immunofluorescence as previously described16 and using a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Rabbit anti-CD20 pAb (Neomarkers; Thermo Fisher Scientific GmbH) revealed by Rhodamine Red X (RRX)–donkey anti–rabbit Ig antibody (Jackson Research/Dianova GmbH) was combined with either: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–anti-Ki67 mAb (MiB-1; DAKO Deutschland GmbH), FITC–anti-CD3 mAb (UCHT1; BD Biosciences), FITC–anti-IgM mAb (G20-127; BD Biosciences), anti-CD1c mAb (C4445; Lifespan BioSciences), FITC–anti-CD27 mAb (M-T271; BD Biosciences), FITC–anti-IgD mAb (IA6-2; BD Biosciences), or with anti-GPIIb/IIIa mAb (2B3A; Enzyme Research Laboratories) and anti-GPIV mAb (3H1265; Lifespan BioSciences). All mAbs were detected with FITC-goat anti–mouse Ig (DAKO Deutschland GmbH). The sections were visualized using a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscope (×200 magnification; Carl Zeiss). Rabbit anti-IgM pAb (DAKO Deutschland GmbH) or anti-CD20 pAb (Neomarkers) was detected with RRX-donkey anti–rabbit Ig and combined with FITC–anti-CD35 mAb (E11; BD Biosciences) or anti-GPIIb/IIIa mAb detected with FITC-goat anti–mouse Ig Ab (DAKO Deutschland GmbH). The sections were visualized by Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscopy (×200 magnification; Carl Zeiss) and analyzed with Zen 2009 light edition (Carl Zeiss). The proportion of total PLNs to GPIIb/IIIa-reactive PLNs was analyzed by costaining with anti-IgM and anti-GPIIb/IIIa on 5 frozen spleens. Details of the Abs used for dual immunofluorescence are summarized in Table 4.

List of antibodies used in dual immunofluorescence experiments

| . | Targets . | Clone . | Dilution . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal antibodies | |||

| Anti-CD1c | B cells in particular MZ analog B cells | C4445 | 1/20 |

| FITC–anti-CD27 | T cells, plasma cells and B cells in particular MZ analog and memory B cells | M-T271 | 1/20 |

| FITC–anti-CD3 | T cells | UCHT1 | 1/50 |

| FITC–anti-IgM | Plasma cells and B cells | G20-127 | 1/20 |

| FITC–anti-IgD | B cells in particular mantle and memory B cells | IA6-2 | 1/20 |

| Anti-GPIIb/IIIa | Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa: a main target of autoantibody in ITP | 2B3A | 1/100 |

| FITC–anti-Ki67 | Proliferating cells | MiB-1 | 1/20 |

| FITC–anti-CD35 | B cells and FDCs | E11 | 1/20 |

| Polyclonal antibodies | None | ||

| Rabbit anti–human CD20 | B cells | pAbs | 1/200 |

| Rabbit anti–human IgM | Plasma cells and B cells | pAbs | 1/400 |

| FITC-goat anti–mouse Ig | pAbs | 1/30 | |

| FITC-donkey anti–rabbit Ig | pAbs | 1/100 | |

| RRX-donkey anti–rabbit Ig | pAbs | 1/100 | |

| RRX-donkey anti–mouse Ig | pAbs | 1/100 |

| . | Targets . | Clone . | Dilution . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal antibodies | |||

| Anti-CD1c | B cells in particular MZ analog B cells | C4445 | 1/20 |

| FITC–anti-CD27 | T cells, plasma cells and B cells in particular MZ analog and memory B cells | M-T271 | 1/20 |

| FITC–anti-CD3 | T cells | UCHT1 | 1/50 |

| FITC–anti-IgM | Plasma cells and B cells | G20-127 | 1/20 |

| FITC–anti-IgD | B cells in particular mantle and memory B cells | IA6-2 | 1/20 |

| Anti-GPIIb/IIIa | Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa: a main target of autoantibody in ITP | 2B3A | 1/100 |

| FITC–anti-Ki67 | Proliferating cells | MiB-1 | 1/20 |

| FITC–anti-CD35 | B cells and FDCs | E11 | 1/20 |

| Polyclonal antibodies | None | ||

| Rabbit anti–human CD20 | B cells | pAbs | 1/200 |

| Rabbit anti–human IgM | Plasma cells and B cells | pAbs | 1/400 |

| FITC-goat anti–mouse Ig | pAbs | 1/30 | |

| FITC-donkey anti–rabbit Ig | pAbs | 1/100 | |

| RRX-donkey anti–rabbit Ig | pAbs | 1/100 | |

| RRX-donkey anti–mouse Ig | pAbs | 1/100 |

MZ indicates marginal zone; ITP, immune thrombocytopenia; and FDC, follicular dendritic cell.

RT-PCR on sections of human spleen

Frozen splenic sections obtained from autoimmune thrombocytopenia (AITP) patients were stained using the HistoGene LCM staining kit (Arcturus). Subsequently, mRNA from the 8 sections was prepared using the PicoPure RNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instruction (Arcturus). Commercial cDNA from normal human spleen (Promega GmbH) and H2O, respectively, were used as positive and negative controls. RT-PCR for Bcl6, Bcl2, and activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AIDCA) mRNA was performed as described previously.11

Statistical analysis

Unpaired datasets were compared using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test and the Fisher exact test, respectively (GraphPad Prism 4 software). P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All values are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise specified.

Results

Reduced numbers of classic GCs but normal numbers of lymphoid nodules in spleens from ITP patients

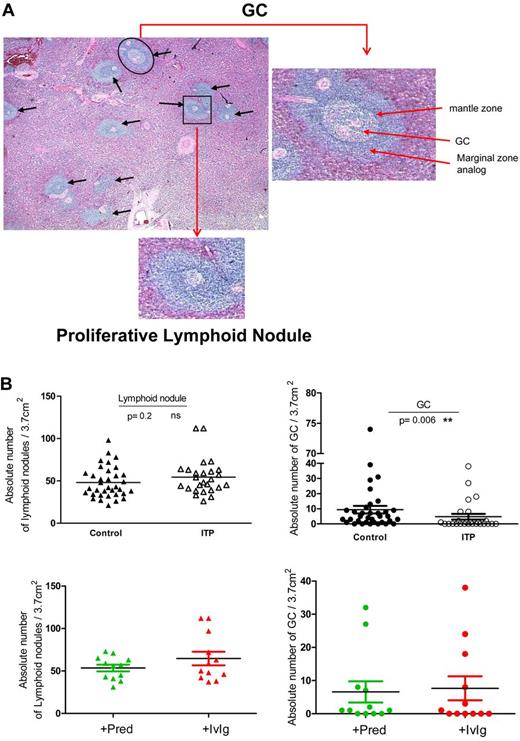

A total of 26 spleens from ITP patients and 35 control spleens were initially examined by standard histology to compare the frequency of GCs (Figure 1A). After H&E staining, densely packed lymphocyte aggregates were identified as shown in Figure 1A (black arrows). GCs were defined as aggregates of cells within lymphoid nodules that were not uniformly basophilic, comprising both light zone (LZ) and dark zone (DZ). The density of GCs (marked by a black circle in Figure 1A) in the white pulp from both groups was assessed microscopically. Notably, the absolute density of GC was significantly decreased in spleens from ITP patients compared with controls (4.7 ± 9.6 vs 9.4 ± 14.7 GCs/3.7cm2; P = .006, Figure 1B). Interestingly, 14 (53%) of 26 of the spleens from ITP patients did not have any detectable GCs in the sections analyzed, whereas only 6 of 35 spleen sections obtained from controls had no identifiable GCs (17.1%; P = .005 compared with ITP spleens, Fisher exact test, 2-sided). Although GCs were substantially reduced in ITP spleens, it should be noted that the few GCs found in ITP spleen had a normal histologic appearance. Separate analysis of primary and secondary ITP did not show significant differences between the frequency of GCs and PLNs (supplemental Figure 1). However, the number of secondary ITP spleens examined was low (n = 6).

Microscopic quantification of GCs and other lymphoid nodules in human spleens. (A) Representative photomicrograph of an H&E-stained section of an ITP spleen with GCs within a lymphoid nodule identified as an aggregate of nonhomogeneously basophilic cells with distinct DZ and LZ (black circle). An enlargement of a characteristic GC is shown on the right. Black arrows indicate lymphoid nodules and the black square indicates a typical PLN within the white pulp. An enlargement of a characteristic PLN is shown underneath. (B) The number of GCs and lymphoid nodules was counted within spleen sections from 26 patients with ITP and 35 controls. ITP patients were grouped according to the underlying treatment before splenectomy as those treated with prednisone (+Pred) or with IvIg in combination with others medications (+IvIg). Each spleen section was normalized to 3.7 cm2 as described in “Quantification of GCs in spleen sections” and visualized with an Olympus BX70 microscope (×50 magnification).

Microscopic quantification of GCs and other lymphoid nodules in human spleens. (A) Representative photomicrograph of an H&E-stained section of an ITP spleen with GCs within a lymphoid nodule identified as an aggregate of nonhomogeneously basophilic cells with distinct DZ and LZ (black circle). An enlargement of a characteristic GC is shown on the right. Black arrows indicate lymphoid nodules and the black square indicates a typical PLN within the white pulp. An enlargement of a characteristic PLN is shown underneath. (B) The number of GCs and lymphoid nodules was counted within spleen sections from 26 patients with ITP and 35 controls. ITP patients were grouped according to the underlying treatment before splenectomy as those treated with prednisone (+Pred) or with IvIg in combination with others medications (+IvIg). Each spleen section was normalized to 3.7 cm2 as described in “Quantification of GCs in spleen sections” and visualized with an Olympus BX70 microscope (×50 magnification).

The significant reduction of GCs in ITP spleens was not related to a reduction in the total number of lymphoid nodules in the white pulp as there was no significant difference between controls and ITP (48.1 ± 18.2 vs 54.5 ± 21.0, P = .2). Importantly, no significant influence of therapy was detected because the number of GCs or lymphoid nodules was not different between patients receiving prednisone alone or IvIg combined with other medications (Figure 1B).

Because ITP spleens contained decreased numbers of GCs but normal numbers of total lymphoid nodules, a detailed analysis of the nature of the non-GC aggregates within the white pulp that did not contain LZ and DZ was undertaken (Figure 1A black square).

Characteristics of PLNs

Of central importance, we observed foci of proliferating cells within the white pulp distinct from GCs in control and ITP spleens. These aggregates of proliferating cells were designated PLNs (Figure 1A black square) and were further characterized.

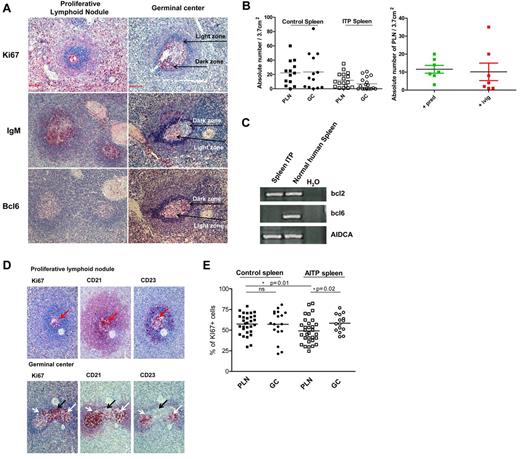

PLNs contained homogenously distributed Ki67+ proliferating cells in both ITP and control spleens (Figure 2A,D) and differed from GCs in which Ki67+ cells were not homogeneously distributed in either ITP or control spleens. GCs, but not PLNs, exhibited notable segregation of cells into regions containing Ki67+ DZ and Ki67− LZ cells. Another striking difference between GCs and PLNs was the distribution of IgM. In both ITP and control spleens, IgM was detectable in PLNs, whereas IgM staining was mostly absent in GCs and when present it was restricted to the LZ (Figure 2A). Thus, the distribution of Ki67 and IgM expression in the lymphoid nodules permitted a clear discrimination between GCs and PLNs. Of note, we never found lymphoid follicles containing both GCs and PLNs.

Characterization of PLNs in human spleen. (A) Representative photograph of Ki67 staining of spleens from 7 controls and 7 ITP patients showing GCs with LZ/DZ polarization and PLNs with a homogeneous distribution of proliferating cells. Representative photograph of IgM staining of spleens from 8 controls and 8 ITP patients showing GCs mostly lacking the expression of IgM and PLNs exhibiting the dense presence of IgM. Sections of 9 ITP and 10 control spleens were stained for expression of Bcl6, which was mostly limited to the DZ of the GCs and absent in PLNs. Visualization with a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscope (×200 magnification). The photomicrographs shown here are from ITP spleens. (B) GCs and PLNs were identified by either Ki67 or IgM stains and the total number of these structures/3.7 cm2 of spleen sections was determined by counting 9 spleen sections from ITP and 11 sections from control. Samples of ITP spleens were divided into those who had received prednisone (Pred) and those who received IvIg just before splenectomy and the number of PLN determined. (C) Comparison of the expression of bcl6, AIDCA, and bcl2 mRNA in spleen from ITP sections versus normal spleen. Distilled water (H2O) was used as a negative control of PCR. Representative RT-PCR of 8 sections from ITP spleen is shown. Each of these sections lacked identifiable GCs. (D) Serial sections of 10 ITP and 10 controls spleens were stained to evaluate the expression of Ki67, CD21, and CD23 in both PLNs (top panels) and GCs (bottom panels). The black arrows mark the dark zone (Ki67+, CD21+/−, and CD23−) and the white arrows indicate the light zone (Ki67+/−, CD21+, CD23+) of a GC. Visualization with Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscope (×200 magnification). The photomicrographs shown here are from ITP spleens. (E) Comparison of the frequency of proliferating cells in splenic GC and PLN after staining with Ki67. Data are expressed as percentage of Ki67+ cells.

Characterization of PLNs in human spleen. (A) Representative photograph of Ki67 staining of spleens from 7 controls and 7 ITP patients showing GCs with LZ/DZ polarization and PLNs with a homogeneous distribution of proliferating cells. Representative photograph of IgM staining of spleens from 8 controls and 8 ITP patients showing GCs mostly lacking the expression of IgM and PLNs exhibiting the dense presence of IgM. Sections of 9 ITP and 10 control spleens were stained for expression of Bcl6, which was mostly limited to the DZ of the GCs and absent in PLNs. Visualization with a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscope (×200 magnification). The photomicrographs shown here are from ITP spleens. (B) GCs and PLNs were identified by either Ki67 or IgM stains and the total number of these structures/3.7 cm2 of spleen sections was determined by counting 9 spleen sections from ITP and 11 sections from control. Samples of ITP spleens were divided into those who had received prednisone (Pred) and those who received IvIg just before splenectomy and the number of PLN determined. (C) Comparison of the expression of bcl6, AIDCA, and bcl2 mRNA in spleen from ITP sections versus normal spleen. Distilled water (H2O) was used as a negative control of PCR. Representative RT-PCR of 8 sections from ITP spleen is shown. Each of these sections lacked identifiable GCs. (D) Serial sections of 10 ITP and 10 controls spleens were stained to evaluate the expression of Ki67, CD21, and CD23 in both PLNs (top panels) and GCs (bottom panels). The black arrows mark the dark zone (Ki67+, CD21+/−, and CD23−) and the white arrows indicate the light zone (Ki67+/−, CD21+, CD23+) of a GC. Visualization with Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscope (×200 magnification). The photomicrographs shown here are from ITP spleens. (E) Comparison of the frequency of proliferating cells in splenic GC and PLN after staining with Ki67. Data are expressed as percentage of Ki67+ cells.

As shown in Figure 1, GCs were rare and often absent in ITP spleens by conventional histologic analysis. Therefore, to analyze the differences between GCs and PLNs in greater detail, specimens of spleens from 10 ITP and 11 control spleens were analyzed after staining for Ki67 and IgM. This analysis (Figure 2B) confirmed that the number of GCs was substantially reduced in ITP versus control spleens (7.0 ± 8.6 vs 23.5 ± 25.7 per 3.7cm2, P = .04). In contrast, the density of PLNs was not significantly decreased in ITP spleens (11.9 ± 10.2 vs 22.2 ± 17.3 per 3.7cm2, P = .08). Of note, no significant influence of therapy was detected, because the number of PLN was not different between patients receiving prednisone alone or IvIg combined with others medications (Figure 2B).

To further assess the nature of PLN, we stained for Bcl6 expression in spleens from 10 controls and 9 ITP patients. Bcl6 is the master transcriptional regulator of GC reactions.17 Interestingly, we observed that the PLNs did not express Bcl6 (Figure 2A), whereas Bcl6 was readily detectable in GCs in both ITP and control spleens. In none of the 37 ITP PLNs and 23 control PLNs examined was Bcl6 staining detected. To confirm this finding, mRNA from frozen sections was prepared from 1 ITP spleen, which contained no identifiable GCs but abundant PLNs. Bcl6 mRNA was not found in any of the 8 sections analyzed, whereas mRNAs of Bcl-2 (member of the Bcl-2 family of apoptosis regulator proteins) and transcripts of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AIDCA),18 were detectable (Figure 2C).

Subsequent experiments analyzed the presence and distribution of FDCs in PLNs and GCs (Figure 2D) from 10 control and 10 ITP spleens. FDCs were defined by the expression of CD23 and CD21 and could be found in both GCs and PLNs. However, the network of FDCs was not polarized in PLNs as characteristically found in GCs in both ITP and control spleens. In PLNs from both ITP and control spleens, the network of FDCs was diffusely distributed within the structure and the FDCs were located in close proximity to proliferating Ki67+ cells (Figure 2D red arrows). In contrast, FDCs within GCs were predominately found in the LZ that contained only a few Ki67+ B cells, but not in the DZ that contained numerous Ki67+ B cells (Figure 2D).

In the context of the Ki67 staining, we evaluated and compared the proliferative status of these splenic structures in greater detail. Within control spleens, the frequency of Ki67+ cells in the PLNs (57.4 ± 12.4%) was not significantly different from in GCs (57.0% ± 17.7%, P = .7). In contrast, PLNs from ITP spleens contained a substantially lower frequency of Ki67-expressing cells (49.0% ± 15.2%) than GC (58.4% ± 10.7%, P = .02) or PLNs of control spleens (P = .01; Figure 2E).

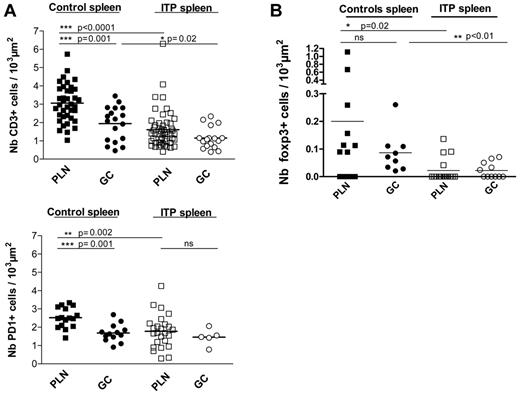

Analysis of T-cell density in PLNs

Because T-cell help as well as the production of certain cytokines and the FDC network are crucial for primary and secondary T-cell dependent B-cell responses,12 we assessed the density of T cells, PD-1+, and Foxp3+ cells within PLNs and GCs in 6 ITP spleens as well as 6 control spleens. The number of CD3+ T cells, PD-1+, and Foxp3+ cells normalized per 103 μm2 (as the mean area) of GCs (51.8 ± 34.7 103 μm2) was significantly larger than that of the PLNs (10.5 ± 7.5 103 μm2). The density of CD3+ T cells was significantly greater in PLNs compared with GCs in control spleens (P = .001), whereas the CD3+ T-cell density was the same in both structures in ITP spleens. However, the density of CD3+ T cells in PLNs of ITP spleens (1.6 ± 1.0 T cells CD3+/103 μm2) was significantly lower (P < .0001) than that found within PLNs of control spleens (3.0 ± 1.0 T cells CD3+/103 μm2; Figure 3A). Within GCs of ITP spleens, the density of T cells was also significantly reduced compared with controls (1.2 ± 0.6 vs 1.9 ± 0.9 T cells CD3+/103 μm2, P = .02). Thus, T cells occurred at substantially lower frequencies in PLNs as well as GCs in ITP versus control spleens, but T cells were not totally excluded from either structure.

Quantitative analysis of CD3+ T cells, PD-1+ TFH, and Foxp3+ cells within PLNs and GCs of ITP and control spleens. The density of CD3+ T cells, PD-1+ TFH, and Foxp3+ cells in the PLNs and GCs were determined by counting the total number of (A) CD3+ T cells, (B) PD-1+ cells, and (C) Foxp3+ cells and normalizing to the respective area of PLNs or GCs (per 103 μm2 as described in “Quantification of cells in splenic lymphoid nodules”). At least 3 ITP and 3 control spleens were analyzed. Visualization with Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscope (×200 magnification).

Quantitative analysis of CD3+ T cells, PD-1+ TFH, and Foxp3+ cells within PLNs and GCs of ITP and control spleens. The density of CD3+ T cells, PD-1+ TFH, and Foxp3+ cells in the PLNs and GCs were determined by counting the total number of (A) CD3+ T cells, (B) PD-1+ cells, and (C) Foxp3+ cells and normalizing to the respective area of PLNs or GCs (per 103 μm2 as described in “Quantification of cells in splenic lymphoid nodules”). At least 3 ITP and 3 control spleens were analyzed. Visualization with Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscope (×200 magnification).

Subsequent studies addressed the expression of PD-1 as a marker of TFH. The TFH density was significantly higher in PLNs compared with GCs of control spleens (Figure 3B), whereas the frequency of PD-1+ cells within the PLNs was significantly lower than in GCs in ITP spleens (P = .002). Interestingly, a striking reduction of PD-1+ cells was observed between GCs and PLNs in control spleens (P = .001), whereas the density of PD-1+ TFH was comparable between GCs and PLNs in ITP spleens.

Further experiments addressed the presence of Foxp3+ Tregs in different splenic structures. Interestingly, the density of Foxp3+ cells was significantly reduced in GCs (P < .01) and PLNs (P < .02) in ITP spleens in comparison to controls (Figure 3C). Notably, about 75% of the PLNs in ITP spleens did not have any Tregs compared with only 30% in controls. Similarly, about 55% of the GCs in ITP spleens did not have any Tregs, while in the controls, no GCs were found without Tregs.

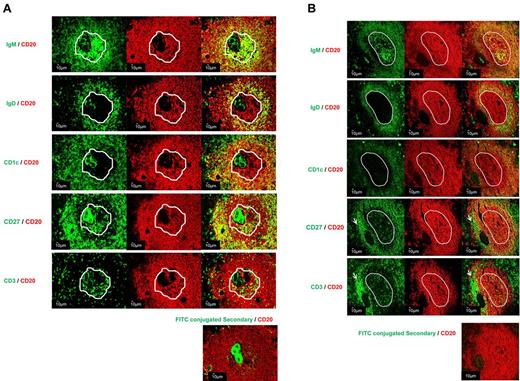

Characterization of B-cell subpopulations in PLNs

To characterize the organization of B cells in PLNs, double immunofluorescence staining was carried out on sections from 3 ITP spleens and 1 control spleen. IgM staining was used to discriminate between GCs and PLNs as shown in Figure 2. In the splenic tissues analyzed, PLNs and GCs contained CD20+IgD−CD27−CD1c− B cells (Figure 4A). As previously noted, IgM was diffusely present in PLNs, although there was only partial overlap with CD20, whereas in GCs the IgM expression was patchy in the LZ. The PLNs and GCs were surrounded by IgM+IgD+CD27− follicular mantle B cells. However, the follicular mantle B cells surrounding GCs and PLNs differed with regard to CD1 expression, with the former being routinely negative whereas the latter expressed CD1c (Figure 4). A narrow marginal zone analog (MZA) region composed of CD20+CD27+CD1c+ B cells was observed surrounding the mantle zone in follicles containing GCs and follicles containing PLNs. No significant difference was noted in the area of the MZA surrounding GCs and PLNs (85.1 ± 36.2 and 86.0 ± 29.7 103μm2, P = .98, data not shown). In MZA, both IgM+ and IgM− memory B cells were identified, although there appeared to be enrichment for IgM− memory B cells in the MZA surrounding PLN-containing follicles.

Detailed characterization of PLNs within spleens from ITP patients. Sections from 4 spleens (3 ITP and 1 control) were examined by double immunofluorescence staining: CD20 (red) with IgD (green), CD1c (green), CD27 (green), or IgM (green). (A) PLN (ITP) and (B) GC (control). The white outline indicates the location of the structures, PLNs and GCs, determined by IgM staining. The presence of T cells in PLNs was analyzed by CD3 (green) and CD20 staining. The arrows designated a T-cell area (B). Control for nonspecific binding was performed on spleen sections using FITC-secondary antibodies and CD20 (red). The sections were analyzed by confocal microscopy using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal or a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscope (×200 magnification; Carl Zeiss).

Detailed characterization of PLNs within spleens from ITP patients. Sections from 4 spleens (3 ITP and 1 control) were examined by double immunofluorescence staining: CD20 (red) with IgD (green), CD1c (green), CD27 (green), or IgM (green). (A) PLN (ITP) and (B) GC (control). The white outline indicates the location of the structures, PLNs and GCs, determined by IgM staining. The presence of T cells in PLNs was analyzed by CD3 (green) and CD20 staining. The arrows designated a T-cell area (B). Control for nonspecific binding was performed on spleen sections using FITC-secondary antibodies and CD20 (red). The sections were analyzed by confocal microscopy using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal or a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscope (×200 magnification; Carl Zeiss).

Detection of ICs bound to the FDC network in PLNs

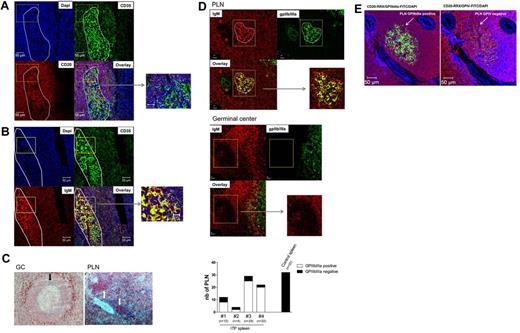

To examine the nature of FDCs, double immunofluorescence staining was performed combining the FDC marker CD35 with CD20 or IgM staining (Figure 5). Confocal microscopic examination of ITP spleen showed no overlap of CD35 and CD20 in the PLNs; nevertheless, CD20+ B cells and CD35+ FDCs were found in close proximity diffusely throughout PLNs as shown in the overlay (Figure 5A). Thus, even though CD20+ B cells and CD35+ FDCs were closely approximated, overlap was only noted between CD35 and IgM, suggesting that the IgM might be bound to FDCs (Figure 5B). In contrast, IgM was barely present in GCs, and when present, IgM was only present in the LZ and also bound by FDCs (Figures 2A,D, 4B, 5C). To delineate whether autoantigen is present in PLNs or GCs, we initially stained for platelet surface antigen, GPIV. Most noteworthy, this autoantigen was not detectable in splenic GCs of either control or ITP spleen as shown Figure 5C. By contrast, ITP splenic PLNs were positive for the GPIV. Of 45 PLNs analyzed for GPIV, 6 PLNs were found to be positive (data not shown). Notably, in these PLNs, GPIV colocalized with IgM. To further analyze the localization of platelet antigens in ITP PLNs, we sought to analyze expression of GPIIb/IIIa. We could not detect this autoantigen in fixed tissue, but we were able to detect it in frozen sections: GPIIb/IIIa was abundantly expressed in most ITP PLNs. Moreover, IgM and GPIIb/IIIa costaining was detected in PLNs (Figure 5D). Notably, all 4 ITP spleens analyzed contained GPIIb/IIIa-positive PLNs, with 73.5 ± 18.9% of PLNs positive for this autoantigen and exhibiting colocalization of IgM with GPIIb/IIIa (Figure 5D). No GPIIb/IIIa positive PLNs (n = 32) or GCs (n = 6) were observed in the control spleens analyzed. Of note, PLNs are specific for one autoantigen or the other, in that no PLNs were identified that were positive for both GPIIb/IIIa and GPIV as representatively shown in Figure 5E. These data strongly suggest the presence of autoantigen, predominantly GPIIb/IIIa, containing ICs on the surface of FDCs uniquely within the PLNs of ITP spleens.

Detection of IgM-ICs bound to the FDC network in PLNs identified in ITP spleens. Sections from 2 ITP spleens were analyzed by immunofluorescence to examine the distribution of (A) DAPI to stain nuclei, CD20 (red), and CD35 (green), and (B) DAPI, IgM (red) and CD35 (green). After staining, the sections were analyzed by confocal microscopy using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal (×200 magnification; Carl Zeiss). The white ellipse designed using Zen 2010 software represents a proliferating lymphoid nodule identified with IgM staining. (C) Detection of GPIV in ITP spleens: PLN (white arrow) and GC (black arrows); ×200 magnification. (D) The proportion of PLNs identified as containing GPIIb/IIIa was analyzed in 4 ITP spleens versus a control spleen and representative GC and PLN. At least 3 sections of 3 different spleens were analyzed from each specimen; n corresponds to the number of PLN analyzed. (E) DAPI to stain nuclei, CD20 (red), and GPIIb/IIIa (green) on the left or GPIV (green) on the right of the figure. The arrow designated 1 PLN positive from ITP spleen.

Detection of IgM-ICs bound to the FDC network in PLNs identified in ITP spleens. Sections from 2 ITP spleens were analyzed by immunofluorescence to examine the distribution of (A) DAPI to stain nuclei, CD20 (red), and CD35 (green), and (B) DAPI, IgM (red) and CD35 (green). After staining, the sections were analyzed by confocal microscopy using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal (×200 magnification; Carl Zeiss). The white ellipse designed using Zen 2010 software represents a proliferating lymphoid nodule identified with IgM staining. (C) Detection of GPIV in ITP spleens: PLN (white arrow) and GC (black arrows); ×200 magnification. (D) The proportion of PLNs identified as containing GPIIb/IIIa was analyzed in 4 ITP spleens versus a control spleen and representative GC and PLN. At least 3 sections of 3 different spleens were analyzed from each specimen; n corresponds to the number of PLN analyzed. (E) DAPI to stain nuclei, CD20 (red), and GPIIb/IIIa (green) on the left or GPIV (green) on the right of the figure. The arrow designated 1 PLN positive from ITP spleen.

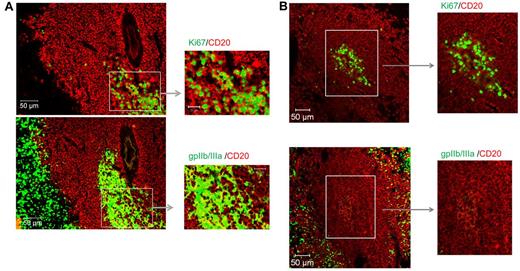

The final studies addressed whether proliferating B cells in proximity to autoantigen can be detected in PLNs of ITP spleens. To examine this, we stained serial sections with CD20/Ki67 and CD20/GPIIb/IIIa. Of importance, Ki67+ proliferating B cells were found in the same PLNs of ITP spleens containing autoantigen GPIIb/IIIa (Figure 6A), but not in the PLNs of control spleens (Figure 6B). Some overlap between CD20 and GPIIb/IIIa was observed in PLNs, suggesting that some of the autoantigen was directly bound to proliferating B cells.

Detection of proliferating B cells and autoantigen within PLNs of ITP spleens. Sections from (A) 2 ITP spleens and (B) 1 control were stained for CD20 (red), Ki67 (green), or GPIIb/IIIa (green) and assessed for the presence of proliferating B cells and B cells in proximity to GPIIb/IIIa. Visualization was carried out with a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscope (×200 magnification).

Detection of proliferating B cells and autoantigen within PLNs of ITP spleens. Sections from (A) 2 ITP spleens and (B) 1 control were stained for CD20 (red), Ki67 (green), or GPIIb/IIIa (green) and assessed for the presence of proliferating B cells and B cells in proximity to GPIIb/IIIa. Visualization was carried out with a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscope (×200 magnification).

Discussion

This study provides evidence of at least 2 different splenic white pulp structures accommodating proliferating B cells, classic GCs, and PLNs. PLNs were identified by the presence of a homogeneous aggregate of proliferating B cells expressing CD20 but not Bcl6 associated with FDCs that lacked polarization. In contrast, GCs contained proliferating Bcl6+ B cells in the DZ and polarized FDCs. In ITP spleens, but not in control spleens, autoantigen-containing ICs bound to FDCs and adjacent to proliferating B cells were found in PLNs but not in GCs. Because GCs were not found to contain autoantigen-containing ICs, PLNs appeared to be a critical structure for the induction and/or maintenance of autoimmunity in ITP. The data are consistent with the conclusion that PLNs in ITP spleen might be the site of chronic autoantigen stimulation. The reduced density of T cells, in particular Tregs, and lack of Bcl6 expression along with the abundance of autoantigen-containing ICs bound to FDCs suggest a unique pathway of B-cell activitation and regulation in PLNs that may be different from that characteristic of GC reactions and could contribute to the persistent autoantibody production in ITP.

An initial finding was that the absolute numbers of GCs was significantly decreased in ITP spleens compared with controls. In contrast, Tavassoli et al found a large number of lymphoid nodules in ITP spleens and nearly all of them were reported to contain GCs.19 Nevertheless, no absolute numbers were provided and the cohort was smaller (n = 12), younger (mean age = 38), and the duration of the disease was shorter than in our cohort. Importantly, this finding could not be confirmed by Hayes et al who found that expanded numbers of GC-like structures were not consistently found in spleens of more long-standing ITP patients.20 Similar to the current finding, GCs could not be identified in 33 (45%) of 73 of ITP spleens examined.

The decrease in the density of GCs in ITP spleens was unlikely to have resulted from immunosuppressive therapy because no significant difference was observed between spleens of patients treated with only prednisone or with IvIg in combination with other medications consistent with an earlier report by Hayes et al.20 Rather, it is more likely that autoimmune responses against platelet surface antigens in ITP are focused in structures that could not be identified as classic GCs.

Ki67 staining clearly defined the second unique site of proliferating B cells in splenic white pulp. These PLNs differed from GC in several important characteristics. First, GCs were polarized into DZ with a large fraction of Ki67+ B cells versus LZ with only a few Ki67+ B cells. This well-known feature of typical GCs21,22 differentiated them from PLNs, which contained homogeneously distributed Ki67+ B cells. With regard to the different sites of B-cell proliferation, a recent study of human spleens23 reported that 7 of 8 normal human spleens contained aggregates of Ki67+ B cells without DZ and LZ that could be similar to the PLNs reported here.

Moreover, FDCs in PLNs were in close contact with proliferating B cells in contrast to GCs, implying that the function of FDCs in PLNs versus GCs may be somewhat different. It is known that human FDCs produce B-cell activating factor (BAFF)24 and that BAFF is necessary for B-cell survival in GCs.25 Whether BAFF promotes B-cell survival in PLNs is currently not known. However, it is possible that the close association of FDCs and proliferating B cells in these structures promotes B-cell responsiveness as BAFF has been shown to enhance activation of B cells from ITP patients26 and is found in large amounts in ITP sera.27

A major function of FDCs in LZ is to display antigen in ICs to LZ B cells that re-express surface Ig.3 In PLNs, the close association of FDCs with proliferating B cells suggests that FDCs may play the additional role of promoting ongoing proliferation of antigen-specific B cells. In addition, FDCs in the PLNs displayed IgM-containing ICs on their surface, whereas this was found less frequently in GCs and then only in LZ. Although ICs containing IgG can bind to FDCs via the Fcγ receptor, IgM-containing ICs have known functions in B-cell biology, including the transportation of antigen to FDCs and thereby promoting GC formation.28 Victoratos and Kollias showed that the deposition of ICs on FDCs provides niches for sustained autoantigen engagement that promoted Bcl6 expression, GC formation, and B-cell differentiation.29 Thus, FDC-bearing ICs appear to be decisive for the direction of B-cell reactivity.

It is important to emphasize that the FDC-bound ICs in ITP spleen frequently contained platelet autoantigens, and especially GPIIb/IIIa. Other platelet autoantigens, including GPIV, were found less frequently, but it is important to note that we did not find PLNs that contained both GPIIb/IIIa and GPIV, suggesting that each PLNs might be specific for a unique autoantigen. Because the autoantigen was found as part of an ICs, this finding suggests that locally produced antibody might play an essential role in the development of these structures. However, the findings that PLNs are largely specific for a particular autoantigen and that not all PLNs are positive strongly suggest that local antibody production might arm the FDCs with the autoantibody involved in specific autoantigen capture and presentation to autoreactive B cells. Notably, platelets expressing CD15430,31 may be able to interact with B cells within PLNs and thereby permit a potential self-perpetuating activation loop. Thus, maintenance of autoimmunity could be explained by persistence of autoantigen at the site of platelet clearance and related to local antibody production in the spleen within PLNs.

One major difference between PLNs and GCs relates to the expression of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Whereas Bcl6 is essential for GC formation32 and is detectable in GCs, PLNs lacked expression of this regulator of GC function. Some levels of B-cell responses are permitted in the absence of Bcl6, but generation of fully functional GCs requires Bcl6.33 T-cell expression of Bcl6 is also required for differentiation of TFH, and a complex interplay of B cells and TFH is involved in the full GC responses. Bcl6 expression appears to be reinforced in TFH cells after contact with pre-GC cells34 and TFH cells provide various functions for induction of the memory B-cell program.35 Because we only had the opportunity to examine Bcl6 expression at a single point in time, it cannot be said with certainty that cells in these structures never express Bcl6. However, a large number of PLNs were examined and expression of Bcl6 was uniformly absent, suggesting that these structures represent B-cell responses in the absence of Bcl6 expression in either B cells or TFH. It is notable that we could detect TFH-expressing PD-1, suggesting that partial differentiation of TFH had occurred. Whether the absence of Bcl6 expression results from ineffective signaling, overexpression of counterregulatory molecules, or immature/pre TFH development is unknown, but the result is a specific B-cell response characterized by proliferation and no polarization of the FDC network loaded with ICs.

The density of T cells within GCs and PLNs of ITP spleens compared with controls was reduced. Interesting, Olsson et al found that the frequency of T cells was identical in the white pulp in ITP and control spleens.36 The differences observed here could be explained because we focused specifically within the proliferating B-cell zones: GCs and PLNs, but not in the entire white pulp. Therefore, the reduction of T cells within GCs or PLNs could be the result of a default of T-cell migration into these B-cell zones instead of the total reduction of T cells in the ITP spleen.

Moreover, we found reduced Treg cells in GCs and PLNs in ITP as has been described by Audia et al.13 In this study, CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ cells were reduced in ITP spleens. Another study showed that 36% of the Treg-deficient mice spontaneously developed autoantibody-mediated thrombocytopenia, and these Tregs were able to prevent the disease.37 In humans, the reduced splenic Tregs could be involved in the emergence of GPIIb/IIIa-reactive T and B cells in the blood of ITP patients that declined in responders to splenectomy.11

The precise nature of PLNs and their relationship to sites of B-cell responsiveness remains to be fully delineated. It should be noted that non-GC aggregates of activated B cells have been described previously in mice usually after vaccination with T-independent antigens and denoted as extrafollicular structures4,38,39 or ectopic lymphoid tissue.40,41 While vaccination protocols preferentially using 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl were used as exogenous antigen, the data are limited to such conditions. However, as suggested previously,38,42 T cell–dependent responses within the white pulp may involve both GC and non-GC structures, thereby permitting a division of labor during antigenic responses. These different structures may reflect different degrees of T-cell dependency as well as differences in the nature and dosage of antigen.42 Jacob et al reported that anatomically isolated GC versus B-cell foci after immunization might have independent founding events.38 They suggested that GCs seem to reflect sites of predominantly intraclonal competition for antigen among sister cells whereas non-GC foci may be sites of interclonal competition between unrelated B cells. As long as there is sufficient BCR cross-linking by the presence of large amounts of autoantigen, in this case presented as FDC-bound ICs, less T-cell signaling via CD40 or CD28 may be required.42 Moreover, platelet-expressed CD15430,31 may partially substitute for TFH in PLNs in ITP. Because antiplatelet antibodies often correlate with disease activity in ITP43 and are usually produced by short-lived plasma cells,44 the involvement of PLNs in the autoimmune response of ITP may also explain this observation, because the differentiation of long-lived plasma cells is considered to be restricted to fully developed GCs.

Together, this study identified nonpolarized PLNs in control and ITP spleens accommodating proliferating Ki67+ B cells adjacent to FDCs that lacked expression of Bcl6. In ITP spleens, these structures contained autoantigen-containing IC bound by FDCs and in close proximity to proliferating B cells. The data suggest that there might be distinct pathways of activated B cells in the spleen leading to anatomically different GC versus PLN structures which may be defined by the nature and/or dosage of the antigen and underlying T-cell dependency.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through grants SFB650/TP16 (T.D., A.S., G.R.B.) and DFG project Do491/7-2 (T.D.).

Authorship

Contribution: C.D., P.E.L., and T.D. designed the study; C.D., S.S., and A.A.K. performed research; C.D., C.L., P.E.L., and T.D. analyzed results; C.D., P.E.L., and T.D. discussed results and wrote the manuscript; and A.A.K., A.S., and G.R.B. evaluated and discussed results, provided critical help, and were involved in final drafting of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Thomas Dörner, MD, Charité–University Medicine Berlin, Berlin, Germany; e-mail: thomas.doerner@charite.de.