Abstract

Soluble immune complexes (ICs) are abundant in autoimmune diseases, yet neutrophil responses to these soluble humoral factors remain uncharacterized. Moreover, the individual role of the uniquely human FcγRIIA and glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI)–linked FcγRIIIB in IC-mediated inflammation is still debated. Here we exploited mice and cell lines expressing these human neutrophil FcγRs to demonstrate that FcγRIIIB alone, in the absence of its known signaling partners FcγRIIA and the integrin Mac-1, internalizes soluble ICs through a mechanism used by GPI-anchored receptors and fluid-phase endocytosis. FcγRIIA also uses this pathway. As shown by intravital microscopy, FcγRIIA but not FcγRIIIB-mediated neutrophil interactions with extravascular soluble ICs results in the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in tissues. Unexpectedly, in wild-type mice, IC-induced NETosis does not rely on the NADPH oxidase, myeloperoxidase, or neutrophil elastase. In the context of soluble ICs present primarily within vessels, FcγRIIIB-mediated neutrophil recruitment requires Mac-1 and is associated with the removal of intravascular IC deposits. Collectively, our studies assign a new role for FcγRIIIB in the removal of soluble ICs within the vasculature that may serve to maintain homeostasis, whereas FcγRIIA engagement of tissue soluble ICs generates NETs, a proinflammatory process linked to autoimmunity.

Introduction

Immune complexes (ICs) are constantly produced in the presence of foreign antigens. Under normal conditions, circulating ICs are rapidly cleared from the bloodstream by mononuclear phagocytes in the liver and spleen and are of little pathologic significance. However, excessive circulating soluble ICs can lodge within the vasculature and eventually accumulate in the extravascular space. The tissue deposition of IgG-ICs is a hallmark of several autoimmune diseases and is considered a key trigger of inflammation in these disorders.1 However, the mechanisms underlying internalization of soluble ICs and the downstream physiologic consequences of this process remain largely unexplored.

Cell surface receptors for IgG-ICs, known as FcγRs, play essential roles in IC-induced inflammation in mice. A deficiency in the Fc common γ-chain (γ−/−), required for the expression of the all murine activating FcγRs, protects mice from tissue injury in a number of autoimmune models as well as the Reverse Passive Arthus (RPA) reaction, a prototypic model of soluble IC-mediated inflammation induced by the passive transfer of antibody and antigen.2 Murine neutrophils express 2 low-affinity activating FcγRs, FcγRIII and FcγRIV, which rely on the ITAM-containing γ-chain for expression and signaling.3 In contrast, human neutrophils express a unique GPI-anchored FcγRIIIB and a single polypeptide ITAM-containing FcγRIIA for which there are no genetic equivalents in mice or other mammals.4 The in vivo roles of these 2 uniquely human neutrophil FcγRs have been recently explored. Expression of human FcγRIIA selectively on neutrophils, and a fraction of monocytes (but not macrophages) restores neutrophil recruitment and susceptibility to glomerulonephritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and the skin RPA reaction in mice lacking their endogenous FcγRs (γ−/−).5,6 Mice expressing either FcγRIIA (FcγRIIA/γ−/−) or FcγRIIIB (FcγRIIIB/γ−/−) at comparable levels elicit neutrophil accumulation, but only FcγRIIA is responsible for tissue injury,5 probably through its ability to promote phagocytosis, reactive oxygen species generation, degranulation, and leukotriene production.4,7 Thus, neutrophils can be recruited via either of their human FcγRs, but FcγRIIA links IgG to organ damage. FcγRIIIB is expressed at 4- to 5-fold higher levels compared with FcγRIIA in human neutrophils.8 Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that FcγRIIIB may alone contribute to tissue injury if expressed at levels seen in human neutrophils.

The physiologic role of FcγRIIIB remains enigmatic. In vitro, crosslinking of FcγRIIIB in human neutrophils induces Ca2+ mobilization,9 promotes actin assembly to prime FcγRIIA effector responses,10 recruits FcγRIIA to lipid rafts to promote ITAM-based signaling11 and induces degranulation, but is unable to signal a respiratory burst and phagocytosis.4 FcγRIIIB's cytotoxic functions described to date rely on FcγRIIA and/or the CD18 integrin Mac-1, which physically associate with and may serve as signaling partners for the GPI-linked FcγRIIIB.4,12 Neutrophil FcγRIIIB alone can tether to immobilized soluble ICs under physiologic flow conditions13,14 and in vivo predominates over FcγRIIA in interacting with soluble ICs that deposit strictly within the vessel wall.5 On the other hand, FcγRIIA is principally required for neutrophil recruitment when soluble ICs formed both within the vasculature and extravascular space lead to overt inflammation.5 These, along with an association of a low copy number of FCGR3B with predisposition to lupus,15,16 led us to postulate that FcγRIIIB may participate in the removal of soluble ICs. A previous study demonstrated a correlation between FCGR3B copy number polymorphisms and IgG binding, but IC uptake was not specifically measured.15

Here, using mice expressing the human FcγRs in the absence of murine activating FcγRs, and the same deficient in Mac-1, allowed us to dissect the contribution of, and the pathways engaged by each of the human neutrophil FcγRs and Mac-1 in the uptake of soluble ICs. Moreover, we provided evidence that engagement of these uniquely human FcγRs by soluble ICs in vivo results in physiologic outcomes that have potential consequences for tissue homeostasis and autoimmunity.

Methods

Intravital microscopy

Soluble ICs were prepared by mixing BSA and anti-BSA antibody at 4-6 times antigen excess as previously described.17 Leukocyte recruitment in the cremaster muscle venules was evaluated in mice 60 minutes after intravenous injection of preformed soluble ICs or BSA. For RPA, anti-BSA antibody (200 μg/300 μL) was injected intrascrotally, followed by the intravenous injection of BSA (300 μg/100 μL). Leukocyte recruitment was evaluated 3 hours later. The procedures for preparation of the cremaster of anesthetized mice and subsequent intravital microscopy were as previously described.17

For confocal intravital microscopy, circulating blood neutrophils were labeled with an intravenous injection of 5 μg AlexaFluor 488-labeled mAb to Gr-1 (RB6-8C5). ICs were labeled in vitro with Cy3-labeled anti–rabbit IgG (1:40) for 20 minutes, and then intravenously injected. Postcapillary venules were selected for analysis of leukocyte-IC interactions. At the end of the experiments, peripheral blood was obtained from the retro-orbital plexus. After RBC lysis, Gr-1–positive neutrophils were analyzed for Cy-3 signal by flow cytometry.

Z-stacks of images were captured by an Olympus Fluo View FV 1000 high-speed, multichannel confocal intravital microscope with a 40× water-dipping objective. Images were acquired at a final magnification of 40× by sequential scanning of the 473-nm green channels and 559-nm red channels. Stacks of images of 1-μm-thick optical sections were acquired, yielding 3-dimensional confocal images of venules.

Image stacks were subsequently analyzed off-line with Imaris (Bitplane). First, adherent neutrophils and deposited ICs were rendered as 3D surfaces based on pixel fluorescence-intensity thresholding for FITC (green) and Cy-3 (red), respectively. The neutrophil objects were then used to create a new fluorescent channel consisting solely of Cy-3–labeled ICs present on or inside of the neutrophil surface. A new surface object was created based on intensity thresholding for the channel containing only neutrophil-associated IC (red surface within neutrophils). Data were analyzed on a per-image basis as total volume of neutrophil-associated ICs divided by total volume of neutrophils in the image defined by FITC-anti–Gr-1 signal as regions of interest.

For analysis of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in vivo, 3 hours after RPA induction, mice were injected with Sytox Green (25 nmol) intravenously, and the cremaster muscle was prepared for intravital confocal microscopy. For each mouse, Sytox Green-positive single NET fibers were counted in 4-7 fields (317.1 μm × 317.1 μm) in the cremaster preparation and averaged. Data are presented as the average number of fibers (± SEM) per millimeter squared of tissue. Signals coming from Sytox Green-positive intact cells were excluded from this analysis. For neutrophil depletion, 100 μg Gr-1 antibody was injected intravenously 24 hours before RPA induction. Neutrophil depletion was confirmed by Gr-1 antibody staining followed by flow cytometric analysis as well as hemavet 950Fs analysis.

Adoptive transfer of BMNs

Bone marrow–derived neutrophils (BMNs) were isolated from femurs and tibias of donor animals using Percoll-gradient centrifugation and stained using the fluorophore 5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate (CMFDA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. A total of 2.0 × 107 stained cells were treated with murine TNF-α (200 ng/mL for 15 minutes), washed and injected intravenously into recipient mice after injection of soluble ICs as previously described.18

In vitro analysis of immune complex uptake by neutrophils and HEK293 cells expressing human FcγRs

For analysis by confocal microscopy, Alexa-488–conjugated Gr-1 antibody–labeled BMNs were incubated with BSA/anti-BSA IC labeled with Cy3 secondary antibody at 37°C. After incubation for 1 hour and extensive washing, the BMNs were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, placed on slides, and subjected to analysis by confocal microscopy. Serials of Z slices were acquired by confocal microscopy and used to reconstruct 3D images of neutrophils and internalized ICs.

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with FcγRIIIB or FcγRIIA cDNA by lipofectamine. After 24 hours, they were trypsinized, placed on poly-L-lysine–coated coverslips, and incubated with BSA/anti-BSA ICs labeled with Cy3 secondary antibody and Alexa-488–conjugated human transferrin (10 μg/mL) or 70-kDa FITC dextran (1 mg/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells were then washed and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and cover-slipped. All samples were analyzed by an Olympus Fluo View FV 1000 high-speed, multichannel confocal microscope with a 60× oil-dipping objective.

For flow cytometric analysis of IC internalization, soluble ICs were prepared by mixing DQ-BSA and anti-BSA antibody. BMNs were incubated with DQ-BSA alone or DQ-BSA/anti-BSA (DQ-sIC) at 4°C for 1 hour, and were further incubated for 1 hour at 4°C or 37°C to promote IC uptake. Cells were then incubated with allophycocyanin-conjugated Gr-1 antibody for 15 minutes. Fluorescence associated with Gr-1–positive gated neutrophils was evaluated by flow cytometry. BMNs were incubated in the presence of 5mM methyl β cyclodextrin, 20μM cytochalasin D, or 80μM dynasore before their incubation with DQ-sIC. For the study of murine FcγRIIB, γ−/− BMNs expressing human FcγRs or γ−/− macrophages were preincubated with 2.4G2 (anti-CD16/CD32) antibody or its isotype control and further incubated with DQ-BSA/anti-BSA ICs at 4°C or 37°C or FITC-BSA–anti-BSA sIC at 4°C for the measurement of IC endocytosis and IC binding, respectively, as detected by flow cytometry.

Stable cell line construction and analysis

HEK293 cell lines stably transfected with FcγRIIIB or FcγRIIA were obtained via single-cell cloning by serial dilution in 96-well plates in the presence of G418 (800 μg/mL). Single-cell clones were examined by flow cytometry, and positive clones were then expanded. For the analysis of Cdc42, stable cell lines were transiently transfected with GFP, GFP-Cdc42 L61 (constitutively active), or GFP-Cdc42 N17 (dominant negative)19 by lipofectamine. After 24 hours, cells were incubated with BSA/anti-BSA ICs labeled with Cy5 secondary antibody for 1 hour and acid washed with 0.2N acetic acid to remove external bound ICs before subjecting samples to flow cytometric analysis of GFP+ cells. For the analysis of Rac1, stable cell lines were transiently transfected with Flag-Epac (control), myc-Rac1 L61 (constitutively active), or myc-Rac1 N17 (dominant negative).20 After 24 hours, cells were incubated with labeled ICs and acid washed. Cells were then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.3% saponin, and stained with anti-flag or anti-myc antibody followed by Alexa-488 conjugated anti–mouse secondary antibody. Flag+ or myc+ cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry. For the analysis of the role of Rho, cells were pretreated with a Rho inhibitor called CT04 (1 μg/mL) for 5 hours and then analyzed for IC internalization by flow cytometry as described for the analysis of cdc42.

Analysis of NETs in human and murine peripheral blood neutrophils

For analysis of NETs in human neutrophils, anticoagulated whole blood was collected from normal donors under a protocol approved by the Human Use Committee Board of Brigham and Women's Hospital. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Human neutrophils were isolated as previously described.21 A total of 2 × 106 neutrophils, resuspended in HBSS without calcium and magnesium, were seeded into each well of 24-well tissue culture plates and incubated with BSA, BSA/anti-BSA ICs, RBCs, IgG coated RBCs, dextran sulfate (0.1 mg/mL), or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; 25 ng/mL) for 3 hours at 37°C with 5% CO2. For experiments with bound BSA/anti-BSA ICs, glass coverslips were coated as previously described5 and placed into each well of 24-well tissue culture plate. For inhibitor studies, neutrophils were preincubated with 25μM DPI (reactive oxygen species inhibitor), 5mM MβCD (lipid raft inhibitor), 20μM cytochalasin D (cytoD; inhibitor of actin polymerization), 10μM PP2 (Src inhibitor), 30μM piceatannol (Syk inhibitor), 20μM LY29004 (PI3K inhibitor), 1μM PI103 (PI3K inhibitor), 5μM UO126 (ERK inhibitor), or DMSO (vehicle control) for 30 minutes before their incubation with BSA/anti-BSA ICs. For antibody blocking experiments, neutrophils were preincubated with functional blocking antibodies to FcγRIIA (10 μg/mL, IV.3) and/or FcγRIIIB (10 μg/mL, 3G8) for 20 minutes before an additional 15-minute incubation with BSA/anti-BSA ICs. At the end of the incubation, supernatant was collected, centrifuged to remove detached cells, and incubated with Sytox Green, at a final concentration of 10nM to detect DNA. The plates were read in a fluorescence plate reader (Wallac victor 1420 multilabel counter; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences) with a filter setting of 485 (excitation)/535(emission). For each experiment, fluorescence values were averaged from 2 replicates after the background was subtracted.

For analysis of NETs released by murine neutrophils, anticoagulated whole blood was collected from mice. Murine peripheral neutrophils were isolated by red blood cell lysis followed by percoll gradient centrifugation. Cells were incubated with ionomycin (4μM), BSA- or BSA/anti-BSA in 96 well, glass-bottom plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 2 hours. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium citrate on ice. After washing and blocking with 3% BSA, cells were incubated for 16 hours at 4°C in 0.3% BSA with 0.5 μg/mL rabbit polyclonal anti-CitH3 followed by AlexaFluor-488–conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Fluorescence images were acquired by a Nikon Eclipse inverted wide-field fluorescence microscope. The percentage of neutrophils with released chromatin was calculated as the ratio of neutrophils with citrullinated histone 3 (CitH3)–positive NET structures to CitH3-positive cells.

Statistical analysis

All data obtained are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were analyzed with the unpaired t test. P < .05 was considered significant.

For further details regarding materials and mice, see supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Results

Characterization of FcγRIIA- and FcγRIIIB-mediated IC internalization in neutrophils in vitro

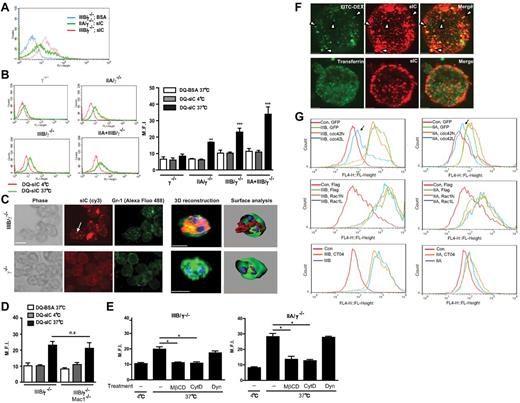

Neutrophils isolated from FcγRIIA/γ−/−, FcγRIIIB/γ−/−, FcγRIIA+FcγRIIIB/γ−/−, and γ−/− mice were evaluated for their ability to bind soluble ICs composed of FITC-BSA and rabbit–anti-BSA. We used rabbit IgG because its binding to FcγRIIA versus FcγRIIIB followed a similar trend to that of human IgG and therefore could serve as a faithful surrogate of human IgG (supplemental Figure 1). We observed that FcγRIIIB binding capacity exceeded that of FcγRIIA (Figure 1A) despite similar expression levels of both receptors at the mRNA level.5 Next, the uptake of ICs was assessed using ICs prepared with anti-BSA antibody and BODIPY-conjugated BSA (DQ-BSA). BODIPY only fluoresces after proteolytic digestion in endocytic compartments, thus allowing measurement of IC endocytosis, which was monitored by flow cytometry (Figure 1B). No IC uptake was observed in γ−/− BMNs, whereas γ−/− BMNs expressing FcγRIIIB or FcγRIIA alone exhibited significant IC internalization that was increased in neutrophils expressing both FcγRs (Figure 1B). DQ-BSA/anti-BSA fluorescence remained in FcγRIIIB neutrophils treated with trypan blue, suggesting that the observed increase in fluorescence was the result of IC internalization (supplemental Figure 2A). IC endocytosis was further confirmed by an approach that exploits the fact that fluorescently labeled secondary antibody has access to surface bound but not internalized ICs when incubated with cells at 4°C (supplemental Figure 2B). Further confirmation of the result that FcγRIIIB can internalize ICs without FcγRIIA was obtained by laser scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy after incubation of FcγRIIIB/γ−/− or γ−/− BMN with fluorophore-conjugated Gr-1 antibody to delineate the plasma membrane surface, and fluorophore-labeled ICs (Figure 1C). Thus, as shown by 3 different methods, FcγRIIIB can endocytose soluble ICs. The inhibitory FcγRIIB on neutrophils may potentially support IC uptake by FcγRIIIB. However, blocking antibody to murine FcγRIIB had no effect on IC internalization by either human FcγR (supplemental Figure 3A), whereas the same blocked the binding of ICs by γ−/− macrophages (supplemental Figure 3B). This is consistent with the very low level of FcγRIIB mRNA in neutrophils versus macrophages (data not shown) and the largely undetectable FcγRIIB protein on the surface of murine neutrophils.22 Next, the possibility that the integrin Mac-1 supports FcγRIIIB-mediated IC uptake was pursued. Neutrophils isolated from FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice lacking this integrin (FcγRIIIB/γ−/−;Mac1−/−) retained their ability to internalize ICs (Figure 1D). Thus, neither FcγRIIB nor Mac-1 supports FcγRIIIB-mediated IC uptake.

FcγRIIIB- and FcγRIIA-expressing neutrophils internalize immune complexes in vitro. (A) Mature neutrophils isolated from the bone marrow of γ−/− mice expressing FcγRIIA (IIA/γ−/−) or FcγRIIIB (IIIB/γ−/−) were incubated with FITC-BSA or FITC-BSA/anti-BSA IC (sIC) at 4°C. Fluorescence associated with samples was evaluated by flow cytometric analysis of Gr-1–positive gated neutrophils, a representative histogram of which is shown. (B) BMNs from indicated mice incubated with DQ-BSA alone or DQ-BSA/anti-BSA (DQ-sIC) at 4°C for 1 hour were further incubated for 1 hour at 4°C, or at 37°C to promote IC uptake. Fluorescence associated with samples was evaluated by flow cytometric analysis of Gr-1–positive gated neutrophils, representative histograms of which are shown (left panel). The average mean fluorescence intensities (M.F.I) obtained by flow cytometry are shown for each mouse strain (right panel). **P < .01, ***P < .001, compared with DQ-BSA alone within each genotype. (C) FITC-anti–Gr-1–labeled BMNs (green) from indicated mice were incubated with ICs labeled with Cy3 secondary antibody (red) at 37°C and subjected to analysis by laser scanning confocal microscopy. Serials of Z slices were acquired by confocal microscopy (left panels) followed by 3D reconstruction and surface analysis (right panels). IC-positive intracellular puncta (arrow) in FcγRIIIB-positive neutrophils were also positive for Gr-1, another GPI-anchored protein. (D) BMNs from FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice or FcγRIIIB/γ−/− lacking Mac1−/− (IIIB/γ−/−/Mac-1) were incubated with DQ-BSA/anti-BSA and assessed as described in panel B. n.s. indicates not significant. (E) Internalization of DQ-BSA/anti-BSA sIC by FcγRIIIB (left panel) and FcγRIIA (right panel) expressing neutrophils pretreated with DMSO (−), cytochalasin D (cytD), MβCD, or dynasore (Dyn) was analyzed as in panel B. *P < .05, compared with DMSO control. (F) FcγRIIIB was transiently expressed in HEK293A cells. Transfected cells incubated with soluble ICs labeled with cy3 secondary antibody (red) combined with FITC-dextran (70 kDa, green, top panel) or Alexa-488–transferrin (green, bottom panel), were evaluated by laser scanning confocal microscopy. Intracellular ICs colocalized with Dextran-containing (arrowheads) but not transferrin-containing intracellular compartments. (G) FcγRIIA or FcγRIIIB stably expressing HEK293A cells were transfected with GFP or GFP-cdc42N (dominant negative) or GFP-cdc42L (constitutive active; top panels), flag-Control or myc-Rac1N (dominant negative), or myc-Rac1L (constitutively active; middle panels) constructs or pretreated with a Rho inhibitor CT04 (bottom panels). Cells were incubated with cy5-labeled sICs. Top panels: GFP-positive cells were analyzed for sIC uptake by flow cytometry. Middle panels: Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-myc or anti-flag antibody followed by Alexa488 anti–mouse antibody. Cells positive for myc or flag were analyzed for sIC uptake by flow cytometry. Bottom panels: Cells were directly analyzed by flow cytometry. Of all the treatments, only constitutively active cdc42 (arrows) decreased sIC uptake by FcγRIIIB and FcγRIIA. N = 3 or 4 independent experiments for panels A-E and G. N = 2 independent experiments for panel F.

FcγRIIIB- and FcγRIIA-expressing neutrophils internalize immune complexes in vitro. (A) Mature neutrophils isolated from the bone marrow of γ−/− mice expressing FcγRIIA (IIA/γ−/−) or FcγRIIIB (IIIB/γ−/−) were incubated with FITC-BSA or FITC-BSA/anti-BSA IC (sIC) at 4°C. Fluorescence associated with samples was evaluated by flow cytometric analysis of Gr-1–positive gated neutrophils, a representative histogram of which is shown. (B) BMNs from indicated mice incubated with DQ-BSA alone or DQ-BSA/anti-BSA (DQ-sIC) at 4°C for 1 hour were further incubated for 1 hour at 4°C, or at 37°C to promote IC uptake. Fluorescence associated with samples was evaluated by flow cytometric analysis of Gr-1–positive gated neutrophils, representative histograms of which are shown (left panel). The average mean fluorescence intensities (M.F.I) obtained by flow cytometry are shown for each mouse strain (right panel). **P < .01, ***P < .001, compared with DQ-BSA alone within each genotype. (C) FITC-anti–Gr-1–labeled BMNs (green) from indicated mice were incubated with ICs labeled with Cy3 secondary antibody (red) at 37°C and subjected to analysis by laser scanning confocal microscopy. Serials of Z slices were acquired by confocal microscopy (left panels) followed by 3D reconstruction and surface analysis (right panels). IC-positive intracellular puncta (arrow) in FcγRIIIB-positive neutrophils were also positive for Gr-1, another GPI-anchored protein. (D) BMNs from FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice or FcγRIIIB/γ−/− lacking Mac1−/− (IIIB/γ−/−/Mac-1) were incubated with DQ-BSA/anti-BSA and assessed as described in panel B. n.s. indicates not significant. (E) Internalization of DQ-BSA/anti-BSA sIC by FcγRIIIB (left panel) and FcγRIIA (right panel) expressing neutrophils pretreated with DMSO (−), cytochalasin D (cytD), MβCD, or dynasore (Dyn) was analyzed as in panel B. *P < .05, compared with DMSO control. (F) FcγRIIIB was transiently expressed in HEK293A cells. Transfected cells incubated with soluble ICs labeled with cy3 secondary antibody (red) combined with FITC-dextran (70 kDa, green, top panel) or Alexa-488–transferrin (green, bottom panel), were evaluated by laser scanning confocal microscopy. Intracellular ICs colocalized with Dextran-containing (arrowheads) but not transferrin-containing intracellular compartments. (G) FcγRIIA or FcγRIIIB stably expressing HEK293A cells were transfected with GFP or GFP-cdc42N (dominant negative) or GFP-cdc42L (constitutive active; top panels), flag-Control or myc-Rac1N (dominant negative), or myc-Rac1L (constitutively active; middle panels) constructs or pretreated with a Rho inhibitor CT04 (bottom panels). Cells were incubated with cy5-labeled sICs. Top panels: GFP-positive cells were analyzed for sIC uptake by flow cytometry. Middle panels: Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-myc or anti-flag antibody followed by Alexa488 anti–mouse antibody. Cells positive for myc or flag were analyzed for sIC uptake by flow cytometry. Bottom panels: Cells were directly analyzed by flow cytometry. Of all the treatments, only constitutively active cdc42 (arrows) decreased sIC uptake by FcγRIIIB and FcγRIIA. N = 3 or 4 independent experiments for panels A-E and G. N = 2 independent experiments for panel F.

The internalization of GPI-anchored proteins occurs via a lipid raft–dependent, actin polymerization–dependent and dynamin-independent endocytic mechanism.23-25 Whether FcγRIIIB engaged a similar pathway was evaluated first using well-characterized pharmacologic inhibitors.26 The lipid raft inhibitor methyl β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), and an inhibitor of actin polymerization, cytochalasin D, abolished FcγRIIIB-dependent IC uptake (Figure 1E) at a dose that had no effect on FcγRIIIB expression, neutrophil viability, or IC binding per se (data not shown). However, a specific dynamin inhibitor dynasore that inhibited zymosan phagocytosis (data not shown) failed to affect FcγRIIIB-mediated IC uptake (Figure 1E). The aforementioned inhibitors had similar effects on IC endocytosis by FcγRIIA-expressing murine neutrophils (Figure 1E).

To further characterize IC uptake, we used molecular biologic approaches in a human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cell line transfected with FcγRIIA or FcγRIIIB. Internalization of GPI-anchored proteins is not clathrin or caveolae dependent but parallels those described for fluid-phase uptake.25,27 Cells expressing either FcγRIIIB or FcγRIIA internalized ICs into endocytic vesicles that cosegregated with a fluid-phase component 70-kDa dextran but not with transferrin, a marker of clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Figure 1F). Small Rho GTPases are key players in endocytic processes.28 Their role was assessed in FcγRIIA or FcγRIIIB stably expressing HEK293 cells (supplemental Figure 4) additionally transfected with constitutively active or dominant negative forms of cdc42 or Rac1, or treated with the specific Rho inhibitor CT04. Only the constitutively active form of cdc42 inhibited FcγRIIIB- and FcγRIIA-mediated endocytosis (Figure 1G). The results are consistent with a previous study showing that persistent activation of cdc42 leads to alterations in the actin architecture that are incompatible with GPI-anchored receptor-mediated endocytosis, whereas Rac1 and Rho do not participate in this process.24

Together, the data suggest that FcγRIIIB and FcγRIIA share a common IC-induced lipid raft–dependent, dynamin-independent, and cdc42-regulated uptake mechanism described for delivery of GPI-anchored proteins to endocytic vesicles.

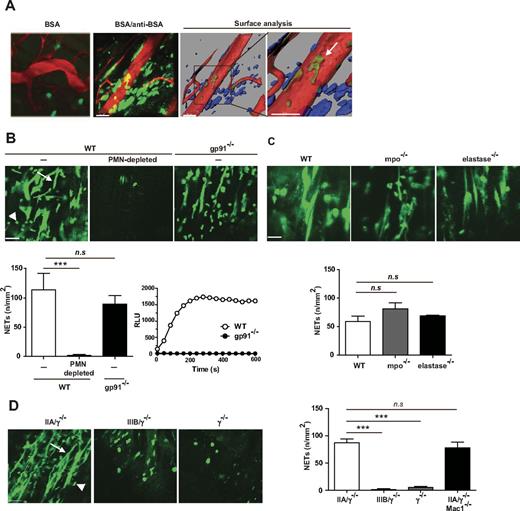

In vivo, FcγRIIA-mediated contact with soluble ICs results in formation of NETs

The physiologic consequence of FcγR-mediated endocytosis was explored in vivo in the RPA reaction in the cremaster muscle induced by the intravenous delivery of BSA and the intrascrotal injection of anti-BSA. The RPA elicits a robust inflammatory response associated with deposition of soluble ICs in the intravascular and extravascular space.1 NETs are DNA fibers released by neutrophils on their interaction with microbes, platelets, or systemic lupus erythematosus ICs.29,30 Here we assessed in real-time whether soluble ICs formed in the RPA reaction triggered the formation of NETs in vivo and the role of FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB in the generation of these structures. Mice were subjected to the RPA, given fluorophore-conjugated anti–Gr-1 antibody to label neutrophils and Sytox Green, a fluorescent nucleic acid stain impermeant to living cells, and their cremaster tissue was prepared for intravital microscopy. Robust Sytox Green-positive NETs were observed in the extravascular space of wild-type mice, with a small fraction also localizing within vessels (Figure 2A). These structures were largely absent in wild-type mice injected with BSA alone (Figure 2A). In addition to neutrophils, mast cells and eosinophils can form DNA extracellular traps.31,32 However, the observed NET structures originated from neutrophils and possibly monocytes, as they were absent in wild-type mice immunodepleted of these leukocyte subsets (Figure 2B). Reactive oxygen species–, myeloperoxidase- and neutrophil elastase–dependent pathways of NET formation have been previously described.33 RPA-induced NET formation was comparable in mice lacking the NADPH oxidase component gp91phox and wild-type counterparts (Figure 2B). Similarly, NET formation was comparable in mice lacking myeloperoxidase or neutrophil elastase, and wild-type animals (Figure 2C), indicating that these pathways were not essential for NETosis.

Engagement of FcγRs results in the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps in vivo. Requirement for FcγRIIA but not the NADPH oxidase, myeloperoxidase (mpo), or neutrophil elastase. The RPA was induced in the cremaster of mice. After 3 hours, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized for intravital microscopy, and the mice were given an intravenous injection of Sytox Green, a DNA binding dye, and tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC) conjugated Dextran (70 kDa), which delineates blood vessels. (A) Left panel: NET-like structures (green) were observed in wild-type (WT) mice subjected to the RPA (BSA/anti-BSA) but not in mice given BSA alone that localized primarily to the extravascular space. Scale bar represents 50 μm. Middle and right panels: The image (BSA/anti-BSA) was subjected to surface analysis of blood vessels (red) and extravascular (blue) and intravascular (green) NET structures. The analysis confirmed the presence of NET-like structures mostly in the extravascular space with a very small fraction present within blood vessels (arrow). (B) Top panels: NET-like structures (arrow) were visible in the cremaster muscle of WT mice (WT, −), although they were absent in WT mice treated with neutrophil-depleting Gr-1 antibody (WT, PMN-depleted). NET-like structures were visible in gp91−/− mice 3 hours after RPA. Scale bar represents 50 μm. Bottom left panel: A graph of the average ± SEM of the number of NETs per millimeter squared of cremaster tissue (n/mm2) for each genotype/condition is shown. N = 3 independent experiments. ***P < .001. n.s. indicates not significant. Bottom right panel: Neutrophils isolated from wild-type and gp91−/− mice were treated with PMA, and ROS generation was evaluated in real-time using a luminol-based assay. (C) Top panels: NET-like structures were visible in the cremaster muscle of WT, mpo−/−, and elastase −/− mice subjected to the RPA. Bottom panel: The quantification of NETs was conducted as described in panel B. N = 3 or 4 mice per genotype. (D) NETosis was evaluated in FcγRIIA/γ−/−, FcγRIIIB/γ−/−, γ−/− mice, and FcγRIIA/γ−/−/Mac-1−/− mice subjected to the RPA. Left panels: NET-like structures were present in the cremaster muscle of FcγRIIA/γ−/−, but not FcγRIIIB/γ−/− or γ−/− mice. In FcγRIIIB/γ−/− and γ−/− mice, Sytox Green was present within cells, which probably reflect the presence of permeable neutrophils. Scale bar represents 50 μm. Right panels: The quantification of NETs for indicated animals was conducted as described in panel B. n = 3 mice per group. ***P < .001. (B-D) Signals coming from Sytox Green-positive intact cells (arrowhead), excluded from this analysis, were similar in all groups.

Engagement of FcγRs results in the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps in vivo. Requirement for FcγRIIA but not the NADPH oxidase, myeloperoxidase (mpo), or neutrophil elastase. The RPA was induced in the cremaster of mice. After 3 hours, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized for intravital microscopy, and the mice were given an intravenous injection of Sytox Green, a DNA binding dye, and tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC) conjugated Dextran (70 kDa), which delineates blood vessels. (A) Left panel: NET-like structures (green) were observed in wild-type (WT) mice subjected to the RPA (BSA/anti-BSA) but not in mice given BSA alone that localized primarily to the extravascular space. Scale bar represents 50 μm. Middle and right panels: The image (BSA/anti-BSA) was subjected to surface analysis of blood vessels (red) and extravascular (blue) and intravascular (green) NET structures. The analysis confirmed the presence of NET-like structures mostly in the extravascular space with a very small fraction present within blood vessels (arrow). (B) Top panels: NET-like structures (arrow) were visible in the cremaster muscle of WT mice (WT, −), although they were absent in WT mice treated with neutrophil-depleting Gr-1 antibody (WT, PMN-depleted). NET-like structures were visible in gp91−/− mice 3 hours after RPA. Scale bar represents 50 μm. Bottom left panel: A graph of the average ± SEM of the number of NETs per millimeter squared of cremaster tissue (n/mm2) for each genotype/condition is shown. N = 3 independent experiments. ***P < .001. n.s. indicates not significant. Bottom right panel: Neutrophils isolated from wild-type and gp91−/− mice were treated with PMA, and ROS generation was evaluated in real-time using a luminol-based assay. (C) Top panels: NET-like structures were visible in the cremaster muscle of WT, mpo−/−, and elastase −/− mice subjected to the RPA. Bottom panel: The quantification of NETs was conducted as described in panel B. N = 3 or 4 mice per genotype. (D) NETosis was evaluated in FcγRIIA/γ−/−, FcγRIIIB/γ−/−, γ−/− mice, and FcγRIIA/γ−/−/Mac-1−/− mice subjected to the RPA. Left panels: NET-like structures were present in the cremaster muscle of FcγRIIA/γ−/−, but not FcγRIIIB/γ−/− or γ−/− mice. In FcγRIIIB/γ−/− and γ−/− mice, Sytox Green was present within cells, which probably reflect the presence of permeable neutrophils. Scale bar represents 50 μm. Right panels: The quantification of NETs for indicated animals was conducted as described in panel B. n = 3 mice per group. ***P < .001. (B-D) Signals coming from Sytox Green-positive intact cells (arrowhead), excluded from this analysis, were similar in all groups.

Next, the contribution of the human FcγRs in IC-induced NET formation was evaluated. NETs were absent in γ-chain–deficient mice albeit Sytox Green did colocalize with Gr-1–positive cells in these animals that may reflect cell permeabilization because of loss of cell viability. FcγRIIA/γ−/− mice subjected to the RPA exhibited extensive NET formation in tissues. In addition to neutrophils, monocytes may contribute to NETosis as FcγRIIA is expressed on 25% of monocytes in the humanized animals.5 However, because FcγRIIA is not present on tissue macrophages of FcγRIIA/γ−/− mice5 and NETs are primarily observed in the tissue (Figure 2A), macrophages probably do not contribute to NETs induced by ICs in our model. In contrast to results with FcγRIIA, FcγRIIIB/γ−/− did not exhibit extracellular chromatin fibers but did exhibit Sytox Green within intact neutrophils as also observed in γ−/− mice (Figure 2D). Notably, the number of transmigrated cells in FcγRIIA/γ−/− is twice that observed in FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice in the RPA.5 Thus, in FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice, we specifically examined areas with Gr-1–positive neutrophils for the presence of NETs. There was no increase in NET-like structures in FcγRIIA+IIIB/γ−/− mice compared with FcγRIIA/γ−/− mice (data not shown). Together, our results suggest that FcγRIIIB alone, expressed at the same level as FcγRIIA in our transgenic mice,5 is not sufficient to induce NETosis. Albeit we cannot rule out the possibility that at much higher expression levels, as that observed in human neutrophils, FcγRIIIB may contribute to NETosis. Finally, neither FcγRIIA mediated neutrophil accumulation (data not shown) nor NET formation (Figure 2D) was affected in FcγRIIA/γ−/− lacking Mac-1 compared with FcγRIIA/γ−/− animals, suggesting that Mac-1 is not required for either of these FcγRIIA functions.

Together, our results suggest that soluble ICs in tissues promote NET formation through a process that does not require the NADPH oxidase, myeloperoxidase, or neutrophil elastase and demonstrate that FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB on neutrophils differ in their ability to generate NETs in vivo.

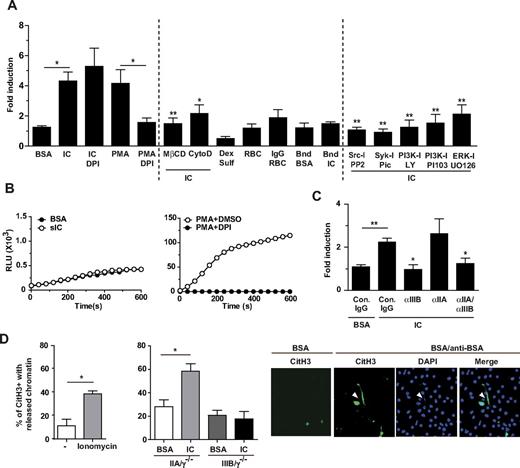

In vitro, endocytosis of soluble ICs by human neutrophils induces NET formation

IC-induced NET formation was further characterized in vitro after incubation of human peripheral blood neutrophils with soluble ICs of BSA and anti-BSA and quantitation of DNA released in the supernatant using Sytox Green (Figure 3A) as previously described.34 Soluble ICs induced significant NET formation in neutrophils after 3 hours that was comparable to that observed with PMA at 6 hours.35 Pretreatment of cells with Diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), a flavoprotein inhibitor of the NADPH oxidase, had no effect on soluble IC-induced NET formation but abolished PMA-induced NET formation (Figure 3A) as reported.33 This is in agreement with the relative lack of reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced after soluble IC endocytosis versus the robust ROS generation after PMA treatment that is inhibited by DPI (Figure 3B). FcγR-mediated endocytosis of ICs was necessary for NET formation as pretreatment with cytochalasin D or MβCD blocked NETs (Figure 3A), whereas these had no effect on PMA-induced NET formation (data not shown). On the other hand, fluid-phase endocytosis per se was not sufficient, as dextran sulfate did not induce NETs (Figure 3A). NETosis also appears to be selective for IC endocytosis as neither phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized RBC nor interaction with plate immobilized ICs (“frustrated phagocytosis”) promoted NET formation (Figure 3A). Insights into the mechanisms of NET formation were gained using inhibitors of signaling molecules potentially engaged by the ITAM-containing FcγRIIA. Syk and Src inhibitors blocked IC endocytosis and therefore NETs. On the other hand, PI3K inhibitors did not block endocytosis but inhibited NET formation after IC stimulation (Figure 3A). Thus, the PI3K pathway may link to NETosis downstream of FcγR internalization.

Soluble ICs induce NETs in vitro in human neutrophils that is dependent on endocytosis and is NADPH oxidase independent. (A) Freshly isolated human peripheral blood neutrophils were incubated without or with BSA, BSA/anti-BSA ICs, RBCs, rabbit IgG-opsonized RBCs, plate-bound BSA (Bnd BSA), plate-bound BSA/anti-BSA ICs (Bnd IC), or dextran sulfate for 3 hours at 37°C in the presence or absence of indicated inhibitors. Neutrophils were incubated with PMA for 6 hours as a positive control. For inhibitor studies, cells were pretreated with DMSO (−), diphenylene iodonium (DPI, ROS inhibitor), MβCD (lipid raft inhibitor), cytochalasin D (cytoD; inhibitor of actin polymerization), PP2 (Src inhibitor), piceatannol (Syk inhibitor), LY29004 (PI3K inhibitor), PI103 (PI3K inhibitor), or UO126 (ERK inhibitor) for 30 minutes before incubation with BSA/anti-BSA IC for 3 hours. Sytox Green was added to the supernatant of cells to detect DNA. The fold increase in fluorescence in samples compared with that detected in neutrophils incubated with buffer alone was calculated. IC-treated neutrophils released more DNA than those treated with BSA. Inhibitors of endocytosis blocked NETs. IgG-coated RBCs, bound BSA/anti-BSA ICs, and dextran sulfate failed to induce NETs. N = 3-20 independent experiments. For cells treated with IC alone, *P < .05 compared to cells treated with BSA. For cells treated with PMA and DPI, *P < .05 compared to cells treated with PMA alone. For cells treated with IC and inhibitors, *P < .05, **P < .01 compared to cells treated with IC alone. (B) Human neutrophils were incubated with BSA alone or sICs (left panel), or PMA in the presence and absence of DPI (right panel). Real-time generation of ROS generation was monitored using a luminol-based assay, representative profiles of which are shown. N = 2 independent experiments. (C) Human neutrophils were preincubated with functional blocking antibody to FcγRIIA (αIIA), and/or FcγRIIIB (αIIIB) or their isotype IgG control antibodies for 20 minutes before an additional 15-minute incubation with sICs. NET formation was inhibited in samples containing an FcγRIIIB blocking antibody. N = 3 independent experiments. For cells treated with IC and control IgG, **P < .01 compared to cells treated with BSA and control IgG. For cells treated with IC and blocking antibodies, *P < .05 compared to cells treated with IC and control IgG. (D) Left panel: Murine peripheral blood wild-type neutrophils were incubated with RPMI or ionomycin (positive control) for 2 hours at 37°C. Middle panel: Indicated transgenic murine neutrophils were incubated with BSA or BSA/anti-BSA ICs for 2 hours at 37°C. Fixed and permeabilized cells were stained for CitH3 and DAPI. The percentages of CitH3-positive cells with released chromatin (ie, number of neutrophils with NET structures divided by the total number of CitH3-positive cells × 100) were determined after the indicated treatments. N = 3 independent experiments. Right panel: Representative pictures of FcγRIIA expressing neutrophils treated with BSA or BSA/anti-BSA. Released chromatin (arrowhead) colocalized with DAPI-positive extracellular DNA.

Soluble ICs induce NETs in vitro in human neutrophils that is dependent on endocytosis and is NADPH oxidase independent. (A) Freshly isolated human peripheral blood neutrophils were incubated without or with BSA, BSA/anti-BSA ICs, RBCs, rabbit IgG-opsonized RBCs, plate-bound BSA (Bnd BSA), plate-bound BSA/anti-BSA ICs (Bnd IC), or dextran sulfate for 3 hours at 37°C in the presence or absence of indicated inhibitors. Neutrophils were incubated with PMA for 6 hours as a positive control. For inhibitor studies, cells were pretreated with DMSO (−), diphenylene iodonium (DPI, ROS inhibitor), MβCD (lipid raft inhibitor), cytochalasin D (cytoD; inhibitor of actin polymerization), PP2 (Src inhibitor), piceatannol (Syk inhibitor), LY29004 (PI3K inhibitor), PI103 (PI3K inhibitor), or UO126 (ERK inhibitor) for 30 minutes before incubation with BSA/anti-BSA IC for 3 hours. Sytox Green was added to the supernatant of cells to detect DNA. The fold increase in fluorescence in samples compared with that detected in neutrophils incubated with buffer alone was calculated. IC-treated neutrophils released more DNA than those treated with BSA. Inhibitors of endocytosis blocked NETs. IgG-coated RBCs, bound BSA/anti-BSA ICs, and dextran sulfate failed to induce NETs. N = 3-20 independent experiments. For cells treated with IC alone, *P < .05 compared to cells treated with BSA. For cells treated with PMA and DPI, *P < .05 compared to cells treated with PMA alone. For cells treated with IC and inhibitors, *P < .05, **P < .01 compared to cells treated with IC alone. (B) Human neutrophils were incubated with BSA alone or sICs (left panel), or PMA in the presence and absence of DPI (right panel). Real-time generation of ROS generation was monitored using a luminol-based assay, representative profiles of which are shown. N = 2 independent experiments. (C) Human neutrophils were preincubated with functional blocking antibody to FcγRIIA (αIIA), and/or FcγRIIIB (αIIIB) or their isotype IgG control antibodies for 20 minutes before an additional 15-minute incubation with sICs. NET formation was inhibited in samples containing an FcγRIIIB blocking antibody. N = 3 independent experiments. For cells treated with IC and control IgG, **P < .01 compared to cells treated with BSA and control IgG. For cells treated with IC and blocking antibodies, *P < .05 compared to cells treated with IC and control IgG. (D) Left panel: Murine peripheral blood wild-type neutrophils were incubated with RPMI or ionomycin (positive control) for 2 hours at 37°C. Middle panel: Indicated transgenic murine neutrophils were incubated with BSA or BSA/anti-BSA ICs for 2 hours at 37°C. Fixed and permeabilized cells were stained for CitH3 and DAPI. The percentages of CitH3-positive cells with released chromatin (ie, number of neutrophils with NET structures divided by the total number of CitH3-positive cells × 100) were determined after the indicated treatments. N = 3 independent experiments. Right panel: Representative pictures of FcγRIIA expressing neutrophils treated with BSA or BSA/anti-BSA. Released chromatin (arrowhead) colocalized with DAPI-positive extracellular DNA.

Receptor-mediated endocytosis, rather than events secondary to IC uptake, is responsible for NETs as these DNA structures were observed within 15 minutes of incubation with ICs and inhibited with functional blocking antibodies to both FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB (Figure 3C). Antibody to FcγRIIIB alone blocked NET formation, whereas anti-FcγRIIA failed to do so (Figure 3C). This correlated with the ability of only anti-FcγRIIIB to significantly block IC binding36 (and data not shown), and the subsequent endocytosis (supplemental Figure 5). Incubation of neutrophils with either antibody alone did not induce NETosis (data not shown). NETosis in the presence of functional blocking antibody to FcγRIIA may be explained by the reported ability of IC ligation of FcγRIIIB alone to drive FcγRIIA phosphorylation and its recruitment to lipid rafts.37,38 The individual roles of FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB in IC-induced NET formation were further assessed in murine neutrophils expressing FcγRIIA or FcγRIIIB alone. Despite the advances in analyzing NETosis in human neutrophils, assay systems to study this process in murine neutrophils in vitro have not been widely reported. NETosis in murine neutrophils was not observed using the DNA release assay, even after PMA treatment for 6 hours (data not shown). Importantly, PMA-induced NET formation in murine and human neutrophils differs39,40 as the kinetics are much slower and the process is much less efficient in murine (10-16 hours treatment gives 25% NETosis) versus human neutrophils. Thus, the assays used in human neutrophils may lack the sensitivity to detect mouse NETs in vitro and were the rationale for establishing a different assay system. Several groups have reported citrullinated histone C3 immunostaining in human neutrophils and the HL60 granulocyte cell line after stimulation with calcium ionophore.41-43 We adopted this assay to detect NETosis in murine neutrophils, using the calcium ionophore ionomycin as our positive control (Figure 3D). PMA failed to give a consistent response (data not shown) and may reflect the inefficiency of PMA in inducing NETosis in mouse neutrophils39,40 and/or the fact that PMA and ionomycin induce NETosis through different mechanisms.44 Next, we stimulated murine neutrophils expressing either FcγRIIA or FcγRIIIB with ICs. We found that FcγRIIA, but not FcγRIIIB, induced the extracellular release of citrullinated histone 3–labeled chromatin upon IC stimulation in vitro (Figure 3D), which is consistent with our in vivo results (Figure 2D). Together, our data in human and murine neutrophils suggest that, although FcγRIIIB alone fails to induce NET formation, FcγRIIIB may play a supportive role in FcγRIIA-induced NET formation that we speculate may be through its ability to capture ICs and subsequently activate FcγRIIA.

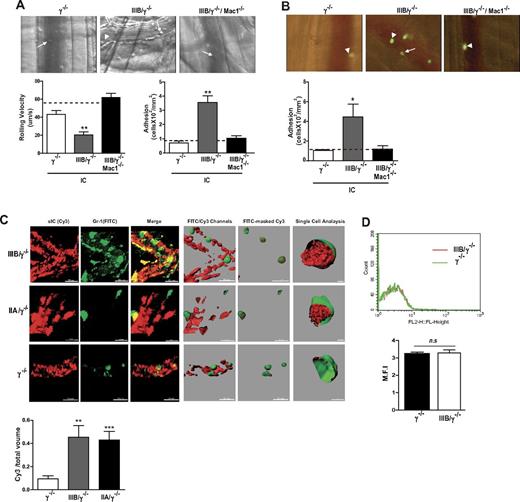

FcγRIIIB-mediated neutrophil tethering to intravascular ICs in vivo is dependent on neutrophil Mac-1

A major objective of our study was to test the hypothesis that FcγRIIIB-mediated neutrophil recruitment results in the removal of soluble ICs deposited within the vessel wall. First, the requirements for FcγRIIIB-mediated neutrophil recruitment were evaluated. FcγRIIIB tethers to intravascularly deposited IC to promote slow neutrophil rolling and adhesion to the vessel wall and predominates over FcγRIIA in this function.5 In this model, preformed soluble ICs injected intravenously rapidly deposit in the postcapillary venules of the cremaster muscle on changes in permeability associated with cremaster exteriorization.17 Unlike the RPA, IC deposition is largely intravascular in this model and neutrophil recruitment occurs in the absence of detectable endothelial activation, platelet deposition, pertussis toxin-sensitive chemokine receptors, mast cells, or complement function.5,17 We examined whether FcγRIIIB-mediated neutrophil tethering in this model requires Mac-1. A deficiency of Mac-1 in mice expressing FcγRIIIB (FcγRIIIB/γ−/−/Mac1−/−) completely abolished neutrophil slow rolling and adhesion (Figure 4A) despite comparable FcγRIIIB expression in these and FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice (supplemental Figure 6). To exclude the possibility that Mac-1 expressed on leukocytes other than neutrophils supports neutrophil FcγRIIIB activity, TNF-primed and CMFDA-labeled γ−/−, FcγRIIIB/γ−/−, or FcγRIIIB/γ−/−/Mac1−/− BMNs were adoptively transferred into wild-type recipients. TNF priming of adoptively transferred BMNs is required for them to interact with deposited ICs.18 We found that FcγRIIIB/γ−/− BMN adhered to intravascular IC in wild-type recipient mice, whereas FcγRIIIB/γ−/−/Mac1−/− BMNs failed to adhere (Figure 4B). Thus, Mac-1 on neutrophils supports FcγRIIIB-dependent neutrophil tethering to intravascular ICs in vivo.

The leukocyte integrin Mac-1 promotes FcγRIIIB-mediated neutrophil recruitment to intravascular ICs and FcγRIIIB mediates IC uptake from within the vessel wall. (A-B) Mice were injected intravenously with preformed soluble ICs, and the rolling velocity and adhesion of leukocytes in the cremaster venules were evaluated. (A) Representative pictures of postcapillary venules from indicated mice with rolling (arrow) and adherent (arrowhead) neutrophils. In FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice, IC deposition slowed the velocity of rolling neutrophils and increased their adhesion compared with γ−/− mice, and FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice without soluble ICs (dotted line). Neutrophils of FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice additionally deficient in Mac-1 no longer supported slow rolling and adhesion. N = 5 mice per group. (B) Wild-type mice were given soluble ICs intravenously and TNF-primed bone marrow–derived, CMFDA-labeled neutrophils from FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice or the same lacking Mac-1 (IIIB/γ−/−/Mac1−/−) were adoptively transferred via the jugular vein. IC deposition increased adhesion of FcγRIIIB-positive neutrophils, although this was not observed with FcγRIIIB-expressing neutrophils that lacked Mac-1. N = 4 mice per group. (C) Soluble ICs generated with BSA and anti-BSA and incubated with Cy3-secondary antibody (sIC, Cy3; red) were injected intravenously together with FITC-labeled Gr-1 antibody, which labels peripheral blood neutrophils (Gr-1, FITC; green). The cremaster of anesthetized animals was exteriorized, and neutrophil-vessel wall interactions were examined by intravital confocal microscopy. Left 3 panels: Slices along the Z-axis were acquired and reconstructed into 3-D Z stacks. The merges of the 2 images are also shown. The images were subjected to surface analysis with Imaris ×64 Version 7.4.2 Software (Bitplane Scientific). Right 3 panels: Surfaces were created from Cy3 (red) and FITC channels (green). sIC (red) within the cell was visualized by creating a surface object from FITC-masked Cy3 channel in 50% transparent neutrophils. Rightmost panel: Neutrophils were cut with a clipping surface through the FITC channel to visualize Cy3 signal only within the cells. IC internalization was determined by calculating the volume ratio between the 2 surfaces objects created by FITC-masked Cy3 (red) and FITC-anti–Gr-1 (green) channels, respectively. There was an increase in the amount of ICs present within FcγRIIIB- or FcγRIIA-positive neutrophils compared with that in γ−/− neutrophils. N = 3 or 4 mice per group. **P < .01. ***P < .001, compared with IC uptake in γ−/− neutrophils. (D) Fifteen minutes after injection of BSA–anti-BSA soluble ICs, peripheral blood was collected. Gr-1–positive neutrophils were analyzed for Cy3 signal by flow cytometry. Minimal fluorescence was associated with these cells, suggesting that IC uptake did not occur in circulating neutrophils. N = 3 mice per group. n.s. indicates not significant.

The leukocyte integrin Mac-1 promotes FcγRIIIB-mediated neutrophil recruitment to intravascular ICs and FcγRIIIB mediates IC uptake from within the vessel wall. (A-B) Mice were injected intravenously with preformed soluble ICs, and the rolling velocity and adhesion of leukocytes in the cremaster venules were evaluated. (A) Representative pictures of postcapillary venules from indicated mice with rolling (arrow) and adherent (arrowhead) neutrophils. In FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice, IC deposition slowed the velocity of rolling neutrophils and increased their adhesion compared with γ−/− mice, and FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice without soluble ICs (dotted line). Neutrophils of FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice additionally deficient in Mac-1 no longer supported slow rolling and adhesion. N = 5 mice per group. (B) Wild-type mice were given soluble ICs intravenously and TNF-primed bone marrow–derived, CMFDA-labeled neutrophils from FcγRIIIB/γ−/− mice or the same lacking Mac-1 (IIIB/γ−/−/Mac1−/−) were adoptively transferred via the jugular vein. IC deposition increased adhesion of FcγRIIIB-positive neutrophils, although this was not observed with FcγRIIIB-expressing neutrophils that lacked Mac-1. N = 4 mice per group. (C) Soluble ICs generated with BSA and anti-BSA and incubated with Cy3-secondary antibody (sIC, Cy3; red) were injected intravenously together with FITC-labeled Gr-1 antibody, which labels peripheral blood neutrophils (Gr-1, FITC; green). The cremaster of anesthetized animals was exteriorized, and neutrophil-vessel wall interactions were examined by intravital confocal microscopy. Left 3 panels: Slices along the Z-axis were acquired and reconstructed into 3-D Z stacks. The merges of the 2 images are also shown. The images were subjected to surface analysis with Imaris ×64 Version 7.4.2 Software (Bitplane Scientific). Right 3 panels: Surfaces were created from Cy3 (red) and FITC channels (green). sIC (red) within the cell was visualized by creating a surface object from FITC-masked Cy3 channel in 50% transparent neutrophils. Rightmost panel: Neutrophils were cut with a clipping surface through the FITC channel to visualize Cy3 signal only within the cells. IC internalization was determined by calculating the volume ratio between the 2 surfaces objects created by FITC-masked Cy3 (red) and FITC-anti–Gr-1 (green) channels, respectively. There was an increase in the amount of ICs present within FcγRIIIB- or FcγRIIA-positive neutrophils compared with that in γ−/− neutrophils. N = 3 or 4 mice per group. **P < .01. ***P < .001, compared with IC uptake in γ−/− neutrophils. (D) Fifteen minutes after injection of BSA–anti-BSA soluble ICs, peripheral blood was collected. Gr-1–positive neutrophils were analyzed for Cy3 signal by flow cytometry. Minimal fluorescence was associated with these cells, suggesting that IC uptake did not occur in circulating neutrophils. N = 3 mice per group. n.s. indicates not significant.

FcγRIIIB and FcγRIIA mediate the clearance of IC in vivo

Next, we evaluated in real-time whether FcγRIIIB-recruited neutrophils internalized intravascular IC deposits in vivo. FcγRIIIB/γ−/− and γ−/− mice were given an intravenous injection of Cy3-labeled preformed ICs together with fluorophore-conjugated Gr-1 antibody, which labels neutrophils, and the cremaster was prepared for confocal intravital microscopy. Z-stack reconstruction of 3D images together with image analysis software revealed that adherent FcγRIIIB-positive neutrophils had significant amount of internalized ICs (Figure 4C). ICs were not observed within circulating neutrophils as assessed by FACS analysis, which indicates that IC uptake occurs at the site of IC deposition (Figure 4D). In FcγRIIA/γ−/− mice, neutrophils failed to be appreciably recruited to primarily intravascular ICs as previously described.5 However, the few interacting neutrophils observed had significant levels of intracellular ICs (Figure 4C). Thus, both FcγRIIIB and FcγRIIA can internalize intravascular ICs in vivo, but FcγRIIIB predominates in this process as this receptor plays the major role in recruitment of neutrophils to intravascular ICs.5 Interestingly, NETs were not observed in this model of largely intravascular ICs (data not shown), which may be the result of plasma DNase activity. The relative absence of inflammation after injection of preformed soluble ICs compared with the RPA, and/or location of the ICs, may be key determinants of IC induced NET formation, a fruitful area for future investigation.

Discussion

Soluble ICs, a hallmark of many autoimmune diseases, are considered key triggers of inflammation-induced tissue damage. Yet, unlike IgG-opsonized targets, endocytosis of complexed IgG in vitro has not been reported to trigger cytotoxic responses typically associated with tissue injury, such as a vigorous NADPH oxidase-mediated oxidative burst and degranulation. Our data demonstrate that FcγRIIIB, in the absence of FcγRIIA and Mac-1, promotes endocytosis through a common pathway engaged by GPI-anchored proteins and fluid-phase pinocytosis. In vivo, FcγRIIIB interaction with soluble ICs deposited primarily within the vasculature promoted IC uptake, suggesting a potentially novel homeostatic function for FcγRIIIB in removal of soluble ICs lodged in blood vessels. On the other hand, in vivo, on exposure to predominantly tissue localized soluble ICs, FcγRIIA but not FcγRIIIB induced NETs, albeit it is possible that at higher levels of FcγRIIIB, as seen in human neutrophils, this GPI-linked receptor may also promote NETosis. Unlike other stimuli,33 soluble IC-induced NETosis in wild-type mice unexpectedly did not require the NADPH oxidase, myeloperoxidase, or neutrophil elastase, suggesting that the requirement for these components is stimulus dependent. The deficiency in these molecules was in the context of wild-type mice expressing murine rather than human FcγRs. Thus, the importance of these pathways to NETosis triggered specifically by the human FcγRs remains to be addressed.

The mode of internalization of IgG via phagocytosis or endocytosis depends on the size of the opsonized complex. Although FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB-expressing murine neutrophils differ in their ability to phagocytose IgG-opsonized particles, and spread on plate-bound IgG complexes (frustrated phagocytosis),5 with only FcγRIIA contributing to these processes, both were equally capable of internalizing soluble ICs. Previous in vitro studies have suggested that GPI-linked FcγRIIIB relays signals into cells via its association with FcγRIIA, integrin Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18), and/or lipid rafts.10,37,38,45,46 The ability of FcγRIIIB to endocytose ICs in the absence of FcγRIIA or Mac-1 suggests, for the first time, that this receptor is capable of transducing signals independent of its previously described signaling partners. FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB follow a dynamin-independent, cdc42-regulated actin-driven pinocytic pathway that does not use the coat proteins, clathrin and caveolin, which is analogous to pathways described for GPI-anchored proteins and fluid-phase endocytosis.47 This is consistent with FcγRIIIB being a GPI-linked protein present in lipid rafts8 and the described translocation of FcγRIIA to lipid rafts on binding of IgG-containing targets or FcγRIIIB crosslinking.11,48,49

Although both FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB share a common endocytic pathway, FcγRIIA, but not FcγRIIIB, expressed at the same level, promoted the formation of NETs in vivo, a proinflammatory event that contributes to host defense but may also be deleterious to the host as it supports thrombosis and autoimmunity.29,50 In vitro, the discrepancy between human and mouse studies in FcγRIIIB's contribution to NETosis is probably the result of the approaches used to achieve a loss of function of FcγRIIA. In human studies, FcγRIIA functional blocking antibody was used while in mouse studies murine neutrophils with or without FcγRIIA were compared. In human neutrophils, even though the ectodomain of FcγRIIA is blocked, the intracellular ITAM motif may still be capable of relaying signals from FcγRIIIB engagement.51 Together, these data suggest that FcγRIIIB may play a supportive role in NETosis but on its own is unable to induce NETosis. Studies in vitro suggested that PI3K downstream of FcγR-mediated endocytosis engages signals necessary specifically for NETosis. Our data (that small soluble ICs with predicted size in the nanometer range48 leads to NET formation, whereas uptake of the larger IgG-RBC (> 3.0μM) or spreading on ICs does not) suggest that the size of the target and/or IC valency matters. The selectivity of soluble IC uptake for DNA release suggests that distinct FcγR-dependent cellular processes trigger NET formation, whereas the occurrence of NETs in the absence of the NADPH oxidase both in vitro and in vivo challenges the paradigm that the oxidative burst is a prerequisite for this process.52

Although the 2 human FcγRs share a similar route of endocytosis, raft-dependent IC uptake by FcγRIIA versus FcγRIIIB may lead to different cellular outputs because lipid rafts are not created equal and can be targeted to different intracellular sites.53 On the other hand, the inflammatory environment may dictate whether FcγRIIIB or FcγRIIA predominate in endocytosis and thus the subsequent cellular response. FcγRIIIB is 4- to 5-fold more abundant and has a higher affinity for IgG than FcγRIIA,36 has a GPI anchor that permits it to protrude further than FcγRIIA, is highly mobile in the membrane bilayer,8 and is present on the microvilli of human neutrophils.13 Thus, FcγRIIIB rather than FcγRIIA is probably preferentially engaged by ICs. It is also well suited for removing ICs under homeostatic function as its engagement does not trigger cytotoxic responses. On the other hand, inflammatory mediators may lead to shedding of FcγRIIIB and favor FcγRIIA interactions with, and subsequent endocytosis of, ICs.6,54 Notably, FcγRIIIB's role in IC clearance may be relevant only in the context of soluble ICs. Indeed, in the case of ICs immobilized to host tissue as in antiglomerular basement membrane nephritis, FcγRIIIB may collaborate to increase neutrophil recruitment and tissue damage.5 This is consistent with the finding that, although copy number polymorphisms leading to lower FcγRIIIB expression increase the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus, a disease associated with soluble ICs, a higher copy number characterizes antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated systemic vasculitis,15,16,55 a disease associated with in situ ICs.

By demonstrating a novel role for neutrophil FcγRIIIB in internalization and removal of soluble ICs deposited in the vasculature, our studies have revealed a previously unappreciated mechanism for clearing soluble ICs. The FcγRIIIB-mediated IC and neutrophil-dependent clearance pathway seems to be supplementary rather than redundant with the known complement-mediated IC clearance by mononuclear phagocytes because FcγRIIIB specializes in clearing ICs trapped within the vasculature, which have probably escaped from complement-dependent clearance in the spleen and liver.56 A role for leukocytes in clearing ICs in renal capillaries has been suggested by early observations that neutrophil depletion delayed removal of IC deposits in peritubular capillaries by several hours57 and clearance of glomerular ICs and restoration of glomerular architecture was preceded by leukocyte recruitment.58 Notably, FcγRIIIB-dependent recruitment to soluble ICs deposited in the vasculature required neutrophil Mac-1 in cis with FcγRIIIB. Thus, although IC uptake in vitro does not require Mac-1, FcγRIIIB-mediated tethering to ICs under physiologic flow conditions requires this integrin.

The relative roles of FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB in human neutrophils have been previously probed. As both FcγRIIA and Mac-1 are present under these conditions, whether FcγRIIIB alone can generate intracellular signals that link to a specific effector response was difficult to ascertain. Our genetic approach allowed us to assign roles for neutrophil FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB in specific functions after endocytosis of soluble ICs and provide an explanation for why neutrophils express 2 FcγRs that differ in their membrane anchor and signaling capacity.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (HL065095 and AR050800, T.N.M.; HL102101, D.D.W.) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad; H.N.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: K. Chen, H.N, R.T., and N.T. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; K.M. and D.D.W. developed the ionomycin-induced NETosis assay in mouse neutrophils; R.S., T.N.M., and K. Croce conceived the experiments; K. Chen and T.N.M. analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the paper and had full access to all original data; and all authors revised the paper for important intellectual content.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tanya N. Mayadas, Center for Excellence in Vascular Biology, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital & Harvard Medical School, 77 Avenue Louis Pasteur, NRB 752O, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: tmayadas@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.