Abstract

Abstract 516

We have previously shown that sex hormones up-regulate telomerase gene expression and telomerase activity in cultured human peripheral blood leukocytes and bone marrow (BM) CD34 cells (Calado et al. Blood 2009). In the current study, we tested the effects of androgens in the preservation of telomeres in vivo using mouse models. We first confirmed that mouse BM cells in vitro responded to 2–5mM testosterone, a primary androgen, with a 1.3–3.8 fold increase (P<0.05) in telomerase RNA expression in BM cells from mice heterozygous for the telomerase RNA gene deletion (Terc+/−) and in wild type controls but had no effect on BM cells from Terc−/− knockout mice. We then treated normal B6, Terc−/−, and Terc+/− mice with testosterone (in corn oil emulsion, 350 micrograms/mouse once weekly by subcutaneous injection) and found 1.3 – 2.1 fold up-regulation in telomerase mRNA expression in blood leukocytes from Terc+/+ and Terc+/− but not Terc−/− mice, suggesting that androgens can potentially up-regulate telomerase activity in vivo.

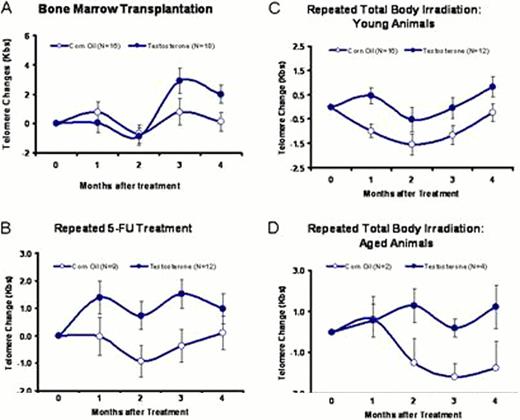

To directly test androgen effect on telomere repair, we injected testosterone (350 micrograms/mouse/week) or corn oil into B6, Terc+/− and Terc−/− mice; there was no testosterone effect on telomere length in either B6 or Terc−/− mice at steady state after six months of treatment. In Terc+/− mice, however, testosterone treatment produced gain of telomere length relative to corn oil controls at four (1.94 ± 1.18 vs 0.49 ± 1.32 Kbs, P<0.4247) and six (2.08 ± 0.52 vs 0.18 ± 0.58 Kbs, P<0.0256) months, indicating that androgen treatment can extend telomeres in vivo under specific conditions. As telomere erosion is minimal under regular conditions in wild-type mice, especially during a short period of time, we hypothesized that androgen effects might be more evident under circumstances of hematopoietic stress and the requirement for accelerated cell replication. Thus, we tested the effect of testosterone on telomere maintenance in three different circumstances. First, we used a BM transplantation model in which we transplanted limiting numbers (5 × 105) of BM cells from Terc+/+, Terc+/−, or Terc−/− donors into lethally-irradiated B6-CD45.1 recipients, and then exposed recipients to weekly injections of testosterone or corn oil for four months. There was no effect of testosterone treatment in recipients of Terc+/+ and Terc−/− BM cells. However, testosterone injection led to telomere gain in recipients of Terc+/− BM cells at three (2.90 ± 0.84 vs 0.79 ± 0.89 Kbs, P<0.0947) and four (2.00 ± 0.61 vs 0.15 ± 0.65 Kbs, P<0.0446) months, respectively (Fig 1A). Second, we used a chemical stress model in which Terc+/− mice received three monthly intraperitoneal injections of 5-fluorouracil at 100 micrograms/gram of body weight; animals were divided into testosterone or corn oil treatment groups. At four months, testosterone treatment resulted in gain of telomere length (1.39 ± 0.60, 0.73 ± 0.50, 1.51 ± 0.62 and 0.97 ± 0.54 Kbs) while telomere attrition occurred in corn oil control animals (−0.03 ± 0.68, −0.93 ± 0.58, −0.37 ± 0.60 and 0.11 ± 0.62 Kbs; Fig 1B), showing a significant overall testosterone effect (P<0.0007) on telomere maintenance. Third, we used repeated irradiation in which Terc+/− mice received three monthly sub-lethal (6 Gys) doses of radiation accompanied by testosterone or corn oil injections. Again, corn oil control mice showed marked telomere attrition (−0.99 ± 0.28, −1.55 ± 0.43, −1.16 ± 0.38 and −0.23 ± 0.36 Kbs) whereas mice that received testosterone had gain or reduced attrition of telomere length (0.46 ± 0.32, −0.51 ± 0.50, −0.03 ± 0.43 and 0.83 ± 0.41 Kbs; P<0.0019; Fig 1C). When the same repeated irradiation protocol was applied to a small group of old Terc+/− mice at 21–26 months of age, telomere attrition was apparent in corn oil control animals at two to four months (−1.50 ± 1.17, −2.68 ± 0.62 and −1.75 ± 1.27 Kbs) but testosterone prevented telomere loss (1.27 ± 0.83, 0.20 ± 0.44 and1.21 ± 1.04 Kbs; P<0.0082; Fig 1D). We conclude that androgens are relatively inactive under normal, steady state conditions, but testosterone at pharmacologic doses can protect telomeres under conditions associated with hematopoietic stress. One implication of these results is the potential utility of sex hormone replacement or pharmacologic administration in patients at risk of secondary hematologic malignancies after chemo- and radiation therapies.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal