Abstract

Abstract 3137

In the absence of a matched sibling donor for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), a MUD is the most often used alternative hematopoietic cell source. Unfortunately, many patients do not have a well-matched MUD. For these patients, CBU transplant is a viable alternative donor source. To optimize hematopoietic engraftment in adult recipients two CBU are often required. We offer dCBU transplantation to patients lacking matched sibling and unrelated donors. This report compares outcomes between those treated with dCBU and MUD HCT at our institution.

From 8/7/2009 through 12/2011, 22 hematologic malignancy patients received dCBU transplants using the conditioning regimen and GVHD prophylaxis described by the group at the University of Minnesota (Barker et al, Blood. 105: 1343, 2005). Thus, we treated patients with fludarabine 75mg/m2 D-8 to D-6, cyclophosphamide 120mg/kg D -7 to D -6, and total body irradiation (TBI) 1320 cGy D -4 to D -1. GVHD prophylaxis included cyclosporine and mycophenolate. We then selected 42 patients treated with MUD HCT (40 well-matched, 2 partially matched) for similar diagnoses from our database as a comparator group. Patients with MUD donors were treated with either etoposide 60mg/kg and TBI 1200cGy if they had acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or busulfan 16mg/kg orally (or the equivalent administered intravenously) D -8 to D -4 and cyclophosphamide 120mg/kg D -3 to D -2. GVHD prophylaxis for MUD patients included tacrolimus and methotrexate, except in one case where mycophenolate was substituted for methotrexate.

The median age of the patients was 49 years (range 20–62 years) with no significant difference between treatment groups. Neither were there differences in diagnoses, HCT-comorbidity index, time from diagnosis to transplant, disease status, or CMV status. However, there was a significant difference with regard to race with 24% of dCBU HCT in African-American patients compared to none of the MUD HCT (P<0.001).

Patients with MUD HCT recovered neutrophils and platelets faster (median 16 and 24 days respectively) compared to dCBU HCT (median 27 and 52 days respectively; P<0.001) resulting in shorter length of stay (median 29 versus 49 days; P<0.001) and contributing to a trend toward improved 100 day mortality (17% vs 38%; P=0.06). There was no significant difference in the incidence or severity for either acute or chronic GVHD between the groups. However, the incidence of infection was significantly greater with dCBU HCT (P<0.001). There was also a trend toward greater non-relapse mortality among patients treated with dCBU HCT(P=0.07) all of which occurred within the first 6 months of transplant.

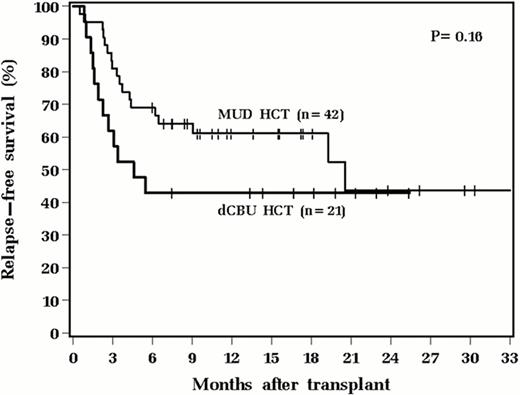

Cox proportional hazards analysis was used to identify univariable and multivariable prognostic factors for overall (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS). Only age (OS: HR1.66; 95% CI 1.08–2.56; P=0.020. RFS: HR1.61; 95% CI 1.07–2.42; P=0.023) and CMV positivity in either donor or recipient (OS: HR 2.61; 95% CI 1.02–6.65; P=0.044. RFS: HR 2.71; 95%CI 1.07–6.86; P=0.035) were significant risk factors. Cell source did not significantly impact either RFS or OS (See figure).

We conclude that although dCBU HCT results in increased early morbidity, there is no significant difference in risk for GVHD, and long-term survival outcomes are similar compared to MUD HCT. dCBU HCT is a useful alternative for patients lacking sibling and MUD donors.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal