Abstract

Nonhuman primate natural hosts for simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIV) develop a nonresolving chronic infection but do not develop AIDS. Mechanisms to explain the nonprogressive nature of SIV infection in natural hosts that underlie maintained high levels of plasma viremia without apparent loss of target cells remain unclear. Here we used comprehensive approaches (ie, FACS sorting, quantitative RT-PCR, immunohistochemistry, and in situ hybridization) to study viral infection within subsets of peripheral blood and lymphoid tissue (LT) CD4+ T cells in cohorts of chronically SIV-infected rhesus macaques (RMs), HIV-infected humans, and SIVsmm-infected sooty mangabeys (SMs). We find: (1) infection frequencies among CD4+ T cells in chronically SIV-infected RMs are significantly higher than those in SIVsmm-infected SMs; (2) infected cells are found in distinct anatomic LT niches and different CD4+ T-cell subsets in SIV-infected RMs and SMs, with infection patterns of RMs reflecting HIV infection in humans; (3) TFH cells are infected at higher frequencies in RMs and humans than in SMs; and (4) LT viral burden, including follicular dendritic cell deposition of virus, is increased in RMs and humans compared with SMs. These data provide insights into how natural hosts are able to maintain high levels of plasma viremia while avoiding development of immunodeficiency.

Introduction

Simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) belong to the group of lentiviruses that in the wild infect nonhuman primates (NHPs). The lentiviruses that cause immunodeficiencies in humans and Asian macaques originated from cross-species transmission of viruses that naturally infect NHPs in Africa.1 Despite persistent infection, SIV-infected natural hosts generally do not progress to AIDS but live healthy life spans despite continual viral replication and high levels of plasma SIV viremia. In contrast, SIV infection of Asian macaques and HIV-1 infection of humans result in chronic infection, and the majority of infected persons progress to AIDS. Dissecting the mechanisms underlying the nonprogressive nature of natural SIV infection will lead to a better understanding of the aspects of HIV infection responsible for the progressive nature of the disease in humans.2,3 Previous studies have demonstrated that natural hosts do not avoid disease progression by immunologic control of the virus because SIV-infected natural hosts can maintain high levels of viremia.4-6 Moreover, experimental depletion of CD8+ T cells does not affect plasma viremia,7,8 and natural hosts do not exhibit more stringent cellular8 or humoral9 control of viremia compared with HIV-infected humans or SIV-infected rhesus macaques (RMs). The lentiviruses that infect African green monkeys (AGMs) and sooty mangabeys (SMs), 2 prototypic natural SIV host species studied, have been shown to be cytopathic to CD4+ T cells from these species with short life spans of infected cells in vivo.10-12 Finally, these viruses can be pathogenic when used to infect other NHPs. Specifically, SIVagm isolates, which naturally infect AGMs, can be used to infect pigtail macaques that subsequently manifest simian AIDS,13 and isolates of SIVsmm can also cause progressive infection in RMs.14-16

The mechanism underlying the natural hosts' maintenance of high levels of plasma viremia without progression to AIDS are unclear, but modulation of viral receptors to protect the critical central memory CD4+ T cell population appears to be part of the answer.17,18 Recent studies have demonstrated that CD4+ T cells from AGMs down-regulate the CD4 receptor19 as CD4+ T cells enter the memory pool and that CCR5 is differentially expressed by SM CD4+ T cells compared with CD4+ T cells from Asian macaques.20,21 Modulation of receptors for SIV by CD4+ T cells in natural hosts suggests that cellular targets for viral replication may differ between natural hosts and non-natural hosts of primate immunodeficiency lentiviruses and that natural hosts have adapted to resist disease in part by shifting the infection to cell populations that may be less essential to the survival of the host.21

Here we have used in situ hybridization with immunohistochemistry, flow cytometric sorting, and quantitative, real-time PCR to study the infection frequencies of carefully defined subsets of naive and memory CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood and lymph nodes (LNs) of chronically SIV-infected RMs and SMs and compared the anatomic distribution of these cells in lymphoid tissues with HIV-infected humans. Our data identify the cellular substrates for SIV infection in natural hosts and non-natural hosts and describe putative mechanisms by which natural hosts are able to maintain high levels of SIV viremia without dying of AIDS.

Methods

Study animals and human cohort

Ten chronically SIVmac239-infected RMs, 9 chronically SIVsmE543-infected RMs, 13 chronically SIVsmm-infected SMs, 8 SIV-uninfected RMs, and 2 SIV-uninfected SMs were used for this study (Table 1). PBMCs were isolated by density centrifugation and LN biopsies were processed to single-cell suspensions or fixed in formalin as previously described.22 Animals were housed and cared in accordance with American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care standards in American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care–accredited facilities, and all animal procedures were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Cancer Institute, or Yerkes Primate Facility, Emory University. Inguinal or axillary LNs (depending on which were palpable) were surgically removed from RMs or SMs. Inguinal LNs that had been obtained from HIV-1–infected persons from previous studies were used in this study (Table 2).23-27 Inguinal LNs were obtained from HIV-1–infected persons who had provided informed consent, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of the University of Colorado.

Animal characteristics

| Animal . | Species . | Viral infection . | wpi or disease stage . | Viral load . | CD4+ T-cell count* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 595 | RM | None | — | 0 | 685 |

| DBM6 | RM | None | — | 0 | 692 |

| DB7H | RM | None | — | 0 | 526 |

| 769 | RM | None | — | 0 | 465 |

| 495 | RM | None | — | 0 | 574 |

| DB9Z | RM | None | — | 0 | 2623 |

| 634 | RM | None | — | 0 | 798 |

| DA6A | RM | None | — | 0 | 465 |

| 591 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 42 | 2.5 × 105 | 186 |

| 594 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 39 | 8.0 × 103 | 292 |

| 597 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 44 | 1.6 × 103 | 484 |

| 759 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 39 | 6.0 × 102 | 526 |

| 760 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 39 | 5.0 × 103 | 296 |

| 762 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 21 | 5.2 × 104 | 625 |

| 764 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 43 | 2.2 × 105 | 134 |

| 767 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 23 | 1.6 × 105 | 163 |

| 768 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 23 | 1.1 × 105 | 265 |

| DB07 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 33 | 5.0 × 105 | 255 |

| DB92 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 33 | 1.0 × 105 | 194 |

| RCo8 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 34 | 2.7 × 105 | 75 |

| RCm6 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 25 | 4.9 × 105 | 153 |

| RCq6 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 13 | 9.7 × 105 | 573 |

| REi9 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 52 | 1.1 × 105 | 168 |

| RHk8 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 50 | 1.8 × 105 | NA |

| RJl9 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 32 | 6.0 × 106 | 706 |

| RUf9 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 5 | 3.4 × 105 | 590 |

| RZz8 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 52 | 1.0 × 106 | NA |

| FEa1 | SM | None | — | 0 | NA |

| FOz | SM | None | — | 0 | 863 |

| FAv | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 1.0 × 104 | 811 |

| FAy | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 5.7 × 105 | 443 |

| FCy | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 5.2 × 105 | 544 |

| FEy | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 2.8 × 105 | 929 |

| FHw | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 5.9 × 104 | 661 |

| FKn | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 1.2 × 105 | 468 |

| FMl | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 3.3 × 105 | 531 |

| FQg | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 6.6 × 104 | 1019 |

| FSs | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 8.5 × 104 | 533 |

| FTr | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 4.2 × 104 | 427 |

| FVs | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 6.7 × 104 | 327 |

| FWv | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 2.7 × 104 | 357 |

| FYm | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 7.6 × 104 | 589 |

| Animal . | Species . | Viral infection . | wpi or disease stage . | Viral load . | CD4+ T-cell count* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 595 | RM | None | — | 0 | 685 |

| DBM6 | RM | None | — | 0 | 692 |

| DB7H | RM | None | — | 0 | 526 |

| 769 | RM | None | — | 0 | 465 |

| 495 | RM | None | — | 0 | 574 |

| DB9Z | RM | None | — | 0 | 2623 |

| 634 | RM | None | — | 0 | 798 |

| DA6A | RM | None | — | 0 | 465 |

| 591 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 42 | 2.5 × 105 | 186 |

| 594 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 39 | 8.0 × 103 | 292 |

| 597 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 44 | 1.6 × 103 | 484 |

| 759 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 39 | 6.0 × 102 | 526 |

| 760 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 39 | 5.0 × 103 | 296 |

| 762 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 21 | 5.2 × 104 | 625 |

| 764 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 43 | 2.2 × 105 | 134 |

| 767 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 23 | 1.6 × 105 | 163 |

| 768 | RM | Experimental SIVsmmE543 | 23 | 1.1 × 105 | 265 |

| DB07 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 33 | 5.0 × 105 | 255 |

| DB92 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 33 | 1.0 × 105 | 194 |

| RCo8 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 34 | 2.7 × 105 | 75 |

| RCm6 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 25 | 4.9 × 105 | 153 |

| RCq6 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 13 | 9.7 × 105 | 573 |

| REi9 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 52 | 1.1 × 105 | 168 |

| RHk8 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 50 | 1.8 × 105 | NA |

| RJl9 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 32 | 6.0 × 106 | 706 |

| RUf9 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 5 | 3.4 × 105 | 590 |

| RZz8 | RM | Experimental SIVmac239 | 52 | 1.0 × 106 | NA |

| FEa1 | SM | None | — | 0 | NA |

| FOz | SM | None | — | 0 | 863 |

| FAv | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 1.0 × 104 | 811 |

| FAy | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 5.7 × 105 | 443 |

| FCy | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 5.2 × 105 | 544 |

| FEy | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 2.8 × 105 | 929 |

| FHw | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 5.9 × 104 | 661 |

| FKn | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 1.2 × 105 | 468 |

| FMl | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 3.3 × 105 | 531 |

| FQg | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 6.6 × 104 | 1019 |

| FSs | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 8.5 × 104 | 533 |

| FTr | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 4.2 × 104 | 427 |

| FVs | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 6.7 × 104 | 327 |

| FWv | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 2.7 × 104 | 357 |

| FYm | SM | Natural SIVsmm | Chronic | 7.6 × 104 | 589 |

wpi indicates weeks postinfection; —, not applicable; and ND, not determined.

At the time of LN biopsy during chronic SIV infection.

Patient characteristics

| Subject no. . | Sex . | Race/ethnicity . | Age, y . | Risk factors . | Viral load* . | CD4+ T-cell count* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-1 | M | White | 50 | IVDU | 4.4 × 103 | 215 |

| 23-2 | M | White | 32 | MSM | 1.0 × 103 | 726 |

| 8-1 | M | Black | 24 | MSM | 1.3 × 104 | 412 |

| 19-1 | M | White | 37 | IVDU | 2.2 × 104 | 705 |

| 10 | M | White | 32 | MSM/IVDU | 2.9 × 104 | 342 |

| 5-1 | M | White | 24 | IVDU/MSM | 3.5 × 104 | 282 |

| 13-1 | M | White | 38 | MSM/IVDU | 4.6 × 104 | 107 |

| 24 | M | Hispanic | 23 | MSM | 4.9 × 104 | 478 |

| 1-1 | M | White | 37 | MSM | 7.4 × 104 | 169 |

| 3-1 | M | Black | 43 | MSM | 1.5 × 105 | 464 |

| Subject no. . | Sex . | Race/ethnicity . | Age, y . | Risk factors . | Viral load* . | CD4+ T-cell count* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-1 | M | White | 50 | IVDU | 4.4 × 103 | 215 |

| 23-2 | M | White | 32 | MSM | 1.0 × 103 | 726 |

| 8-1 | M | Black | 24 | MSM | 1.3 × 104 | 412 |

| 19-1 | M | White | 37 | IVDU | 2.2 × 104 | 705 |

| 10 | M | White | 32 | MSM/IVDU | 2.9 × 104 | 342 |

| 5-1 | M | White | 24 | IVDU/MSM | 3.5 × 104 | 282 |

| 13-1 | M | White | 38 | MSM/IVDU | 4.6 × 104 | 107 |

| 24 | M | Hispanic | 23 | MSM | 4.9 × 104 | 478 |

| 1-1 | M | White | 37 | MSM | 7.4 × 104 | 169 |

| 3-1 | M | Black | 43 | MSM | 1.5 × 105 | 464 |

IVDU indicates intravenous drug user; and MSM, men having sex with men.

At the time of LN biopsy during chronic HIV infection.

Cell-associated SIV DNA quantification

For flow cytometric studies, PBMCs or LN mononuclear cells (LNMCs) were stained with the live dead exclusion dye Aqua blue (Invitrogen) and then with antibodies to CD3 (clone SP34-2; BD Biosciences PharMingen), CD4 (clone L200; BD Biosciences PharMingen), CD279/PD-1 (clone J105; eBioscience), CD278/ICOS (clone C398.4A; BioLegend), CD95 (clone DX2; BD Biosciences PharMingen), CD197/CCR7 (clone 3D12; BD Biosciences PharMingen), CD195/CCR5 (clone 3A9; BD Biosciences PharMingen), and CD28 (clone CD28.2; Beckman Coulter). Cells were then washed, permeabilized (Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer; BD Biosciences PharMingen), and stained intracellularly with fluorescent-conjugated monoclonal antibodies to CD152/CTLA-4 (clone BNI3; BD Biosciences PharMingen) and Ki-67 (clone B56; BD Biosciences PharMingen).

The SIV infection frequency of naive, central memory, TFH, and effector memory CD4+ T cells was determined by real-time PCR analysis of flow cytometrically sorted subsets. Naive CD4+ T cells were defined as live, CD3+CD4+CD28+CCR7+CD95− lymphocytes; central memory CD4+ T cells were defined as live, CD3+CD4+CCR7+CD95+ lymphocytes; effector memory CD4+ T cells were defined as live, CD3+CD4+CCR7−CD95+/− lymphocytes; and LN-resident TFH cells were defined as live, CD3+CD4+CD95+CCR7−PD1+CTLA4+ICOS+.

CD4+ T-cell subsets were sorted using a FACSAria II using FACSDiva Version 6.1.3 software (BD Biosciences PharMingen). Sorted cells were then lysed using 25 μL of a 1:100 dilution of proteinase K (Roche Diagnostics) in 10mM Tris buffer. Quantitative PCR was performed using 5 μL of cell lysates per reaction. Reaction conditions were as follows: 95°C holding stage for 5 minutes, and 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds followed by 60°C for 1 minute using the Taq DNA polymerase kit (Invitrogen). The sequence of the forward primer for SIVmac239 is GTCTGCGTCATYTGGTGCATTC. The reverse primer sequence is CACTAGYTGTCTCTGCACTATRTGTTTTG. The probe sequence is CTTCRTCAGTYTGTTTCACTTTCTCTTCTGCG. The sequence of the forward primer for SIVsm (used to detect SIVsmE543 or SIVsmm) is GGCAGGAAAATCCCTAGCAG, the reverse primer sequence is GCCCTTACTGCCTTCACTCA, and the probe sequence is AGTCCCTGTTCRGGCGCCAA. Sorted cells were then lysed and quantitative real-time PCR was performed. For cell number quantitation, monkey albumin was measured as previously described.28 The PCR machine used was the StepOne Plus (Applied Biosystems), and the analysis was performed using StepOne software (Applied Biosystems). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Version 5 using the Mann-Whitney t test.

HIV-1 and lineage-specific SIV in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and quantitative image analysis

HIV-1 in situ hybridization was performed as previously described.29,30 To ensure optimal detection of productively infected cells from both SIVsmm- and SIVsmE543-infected SMs and RMs, respectively, and SIVmac239-infected RMs; and because lineage 1 SIVsmm viruses infected the highest proportion of the SMs (4 of 10) in our cohort and SIVsmE543 was generated from cross-species transmission of SIVsmm lineage 1 into a rhesus macaque,31 we designed a new set of SIVsmm lineage 1 (designed from the transmitted/founder SIVsmE660 full-length infectious clone SIVsmE660_CG7G) and SIVmac239 specific in situ hybridization riboprobes for these experiments. These newly designed SIVsmmE660 and SIVmac239 riboprobes were generated using the same strategy to ensure comparable SIV gene coverage and probe synthesis methodology. These riboprobes yielded an ∼ 10-fold increased sensitivity in detection of SIV vRNA+ cells compared with previously used and commercially available riboprobe cocktails.32 All SIV riboprobes were generated by PCR-based cloning of target regions in gag, pro, pol, vif/vpx/vpr, env, and nef (9 riboprobes) of roughly equal size (∼ 600 bp) allowing for equal stochiometric molar equivalent riboprobes in our riboprobe cocktail, using primers with either phage T3 (sense) or T7 (antisense) promoter sequences cloned upstream of the viral sequence.

SIV in situ hybridization was modified from previously published lentiviral in situ hybridization procedures.29 In brief, 5-μm tissue sections were mounted on Superfrost Plus Microscope Slides (Fisher Scientific), dewaxed in xylenes, rehydrated through graded ethanol, and placed in HyPure molecular biology grade H2O (Hyclone, Thermo Scientific). Slides were immersed in 0.2N HCI for 30 minutes, 0.15M triethanolamine (pH 7.4) for 15 minutes, and 0.005% digitonin for 5 minutes, all at room temperature. Slides were then incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C in 20mM Tris-HCL containing 2mM CaCI2 and proteinase K (5 μg/mL). After the slides were removed and washed in HyPure molecular biology grade H2O, they were acetylated (0.25% acetic anhydride) for 20 minutes and then placed in 0.1M triethanolamine (pH 8.0) until hybridization. The sections were then covered with hybridization solution (50% deionized formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 0.6M NaCI, 0.4 mg/mL yeast RNA, Ambion Inc; and 1 × Denhardt medium in 20mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.2, with 1mM EDTA) containing 0.4-0.l ng/μL pooled SIVsmE660 or SIVmac239 riboprobes and hybridized for 18 hours at 48°C. After hybridization, slides were washed in 5 × saline sodium citrate (SSC) at 42°C for 20 minutes, 2 × SSC in 50% formamide at 50°C for 20 minutes, 1 × riboprobe wash buffer (RWB; 0.1 M TRIS-HCL pH 7.5, 0.4M NaCl, 0.05M EDTA pH 8.0) at 37°C with ribonuclease A (25 μg/mL), and T1 (25 units/mL) for 30 minutes. After washing in RWB, 2 × SSC, and 0.1 × SSC at 37°C for 15 minutes each, sections were transferred to 1 × Tris-buffered saline (TBS; Boston BioProducts) containing 0.05% Tween-20 (TBS-Tween). Tissues were blocked in sheep block (TBS containing 2% sheep serum and 0.5% casein) for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated with sheep Fab antidigoxigenin conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Roche Applied Science) at 1:500 and mouse anti-CD20 (clone L26; Dako North America) 1:200 in sheep block overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed in TBS-Tween and incubated with a biotin-free polymer anti–mouse HRP system (Mouse Polink-1; Golden Bridge International) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Slides were washed in TBS-Tween and incubated ImmPACT NovaRED Peroxidase Solution (SK-4805; Vector Laboratories) for 10-15 minutes and washed in TBS-Tween. Slides were then incubated with the alkaline phosphatase substrate NBT/BCIP containing levamisole (Roche Applied Science) for 4-18 hours and placed into double-distilled H2O, covered in Clear-Mount (Electron Microscopy Systems), dried, cleared in xylenes, and coverslipped with Permount (Fisher). Immunohistochemistry was performed using a biotin-free polymer approach (Mouse Polink-1 AP; Golden Bridge International) on 5-μm tissue sections mounted on glass slides, which were dewaxed and rehydrated with double-distilled H2O. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating sections in 0.01% citraconic anhydride with 0.05% Tween-20 (pH 7.4; Sigma-Aldrich) in a pressure cooker set at 122°C for 30 seconds. Slides were incubated with protein blocking buffer (TBS with 0.05% Tween-20 and 0.5% casein) for 10 minutes. Mouse anti-SIVmac251 p17 Gag monoclonal (clone KK59; obtained through the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health from Dr Karen Kent and Ms Caroline Powell) with known cross-reactivity to SIVmac and SIVsmm lineages33 or HIV-1 p24 Gag (clone Kal-1, Dako North America) were diluted 1:100-1:500 in blocking buffer and incubated overnight at 4°C. Tissue sections were washed and incubated with the Mouse Polink-1 AP reagent (Golden Bridge International) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Sections were developed with Warp Red (Biocare Medical) for 10-15 minutes, counterstained with hematoxylin, and mounted in Permount (Fisher Scientific). All stained slides were scanned at high magnification (×200-400) using the ScanScope CS System (Aperio Technologies) yielding high-resolution data for the entire tissue section. Each high-resolution whole LN section and anatomic compartment of interest (ie, B-cell follicles and paracortical T-cell zone) was outlined with the Aperio Imagescope pen tool and the respective surface area and fraction of each compartment per LN area determined using values extracted from Imagescope (Aperio Technologies). Within each LN anatomic compartment, the SIV vRNA+ cells were manually counted and the fraction per compartment and per millimeter squared was calculated.

Results

Infection frequencies of peripheral blood CD4+ T-cell subsets

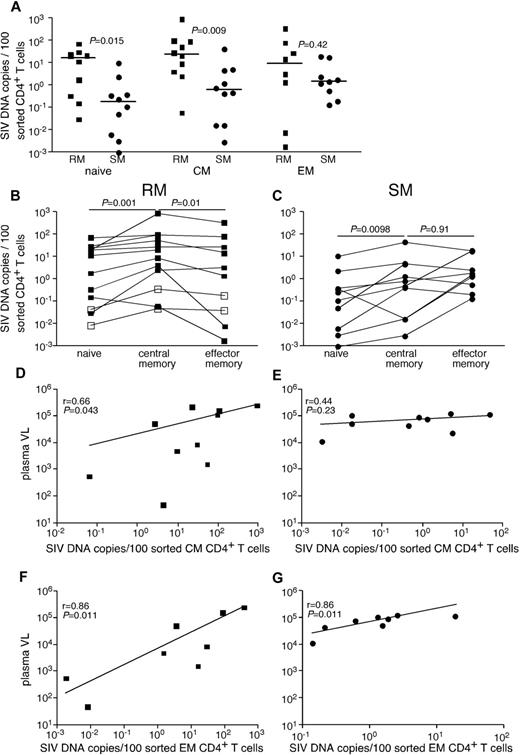

Given the genetic similarities between SIVsmE543 and SIVsmm, we were able to develop a quantitative real-time PCR assay that could detect SIV from both SIVsmm-infected SMs and SIVsmE543-infected RMs. Initially, we compared infection frequencies among subsets of CD4+ T cells, which we flow cytomterically sorted from peripheral blood of chronically SIVsmE53-infected RMs and SIVsmm-infected SMs (Figure 1A). Specifically, we examined infection frequencies of naive CD4+ T cells, CD4+ central memory (TCM) cells, and CD4+ effector memory (TEM) cells. Although cells from each subset of CD4+ T cells were infected by SIV in vivo, the frequency of infected cells was greater in RMs than SMs for naive and TCM CD4+ T cells (Figure 1A). RMs had on average a 30-fold higher frequency of infected TCM CD4+ T cells and similar infection frequencies among TEM CD4+ T cells compared with SMs. In both RMs (Figure 1B) and SMs (Figure 1C), naive CD4+ T cells were significantly less infected by SIV than TCM cells. However, consistent with previous reports,21 while at steady state, CD4+ TCM cells were more frequently infected than CD4+ TEM cells in RMs (Figure 1B), in SMs TCM and TEM CD4+ T cells were infected at similar frequencies (Figure 1C). Interestingly, infection frequencies of both TCM and TEM cells correlated with plasma viremia in RMs, but infection frequencies of only the TEM cells correlated with plasma viremia in SMs (Figure 1D-G). This is of particular interest given the similar plasma viremia between our cohorts of SIV-infected RMs and SMs.

SIV infection of CD4+ T-cell subsets in peripheral blood of RMs and SMs. Naive (CD28dullCCR7+CD95−), TCM (CCR7+CD95+), and TEM (CCR7−CD95+) CD4+ T cells were flow cytometrically sorted from peripheral blood of SIVsmmE543-infected RMs (■), SIVmac239-infected RMs (□), and SIVsmm-infected SMs (●), and infection levels of individual subsets were determined by quantitative PCR. Infection frequencies of individual subsets are compared between RMs and SMs (A). Infection frequencies of different subsets are compared within RMs (B) and SMs (C). Horizontal lines represent the median. P values are based on the Mann-Whitney test (A) or the Wilcoxon matched pairs test (B-C). Correlation between plasma viral loads and infection frequencies of TCM (D-E) and TEM (F-G) in peripheral blood of SIV-infected RM (D,F) and SIV-infected SM (E,G). Lines are based on linear regression and r and P values are based on Spearman rank correlation coefficient.

SIV infection of CD4+ T-cell subsets in peripheral blood of RMs and SMs. Naive (CD28dullCCR7+CD95−), TCM (CCR7+CD95+), and TEM (CCR7−CD95+) CD4+ T cells were flow cytometrically sorted from peripheral blood of SIVsmmE543-infected RMs (■), SIVmac239-infected RMs (□), and SIVsmm-infected SMs (●), and infection levels of individual subsets were determined by quantitative PCR. Infection frequencies of individual subsets are compared between RMs and SMs (A). Infection frequencies of different subsets are compared within RMs (B) and SMs (C). Horizontal lines represent the median. P values are based on the Mann-Whitney test (A) or the Wilcoxon matched pairs test (B-C). Correlation between plasma viral loads and infection frequencies of TCM (D-E) and TEM (F-G) in peripheral blood of SIV-infected RM (D,F) and SIV-infected SM (E,G). Lines are based on linear regression and r and P values are based on Spearman rank correlation coefficient.

LN compartmentalization of viral replication

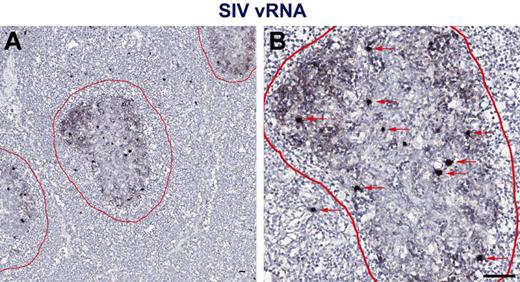

While measuring plasma viremia by quantitative RT-PCR represents a convenient approach for assessing viral replication in vivo, several studies have shown that active viral replication primarily occurs within secondary lymphoid tissues.29 Therefore, to assess individual anatomic niches important for viral replication in vivo in HIV-1 infected persons with progressive HIV-1 infection and progressive SIV infection in RMs and nonprogressive SIV infection in SMs, we performed in situ hybridization for HIV/SIV RNA in paraffin-embedded LNs from chronically HIV-infected humans and SIV-infected RMs and SMs (Figure 2). To ensure optimal detection of productively infected cells from both SIVsmm- and SIVsmE543-infected SM and RM, respectively, and SIVmac239-infected RMs, and because lineage 1 SIVsmm viruses infected the highest proportion of the SMs (4 of 10) in our cohort and SIVsmE543 was generated from cross-species transmission of SIVsmm lineage 1 into a rhesus macaque,31 we designed a new set of SIVsmm lineage 1 (designed from the transmitted/founder SIVsmE660 full-length infectious clone SIVsmE660_CG7G) and SIVmac239 specific in situ hybridization riboprobes for these experiments. Performing in situ hybridization assays using HIV-1, SIVsmm lineage 1, and SIVmac239 specific riboprobes, we were easily able to distinguish vRNA from follicular dendritic cell (FDC)–trapped virons and vRNA from productively infected cells (Figure 2). We quantified the number of SIV RNA+ cells within the LNs and found that consistent with our analysis based on flow cytometry sorted cells showing increased infection frequencies of CD4+ T-cell subsets in SIVsmE543-infected RMs compared with SIVsmm-infected SMs (Figure 1), LNs from SIV-infected RMs harbored on average 4.9-fold higher numbers of productively infected cells (per millimeter squared) compared with SIVsmm-infected SM (Figure 3A). RMs also had higher numbers of productively infected cells compared with HIV-1–infected humans (Figure 3A), consistent with higher average plasma viremia in RMs (median = 222 000) compared with humans and SMs (medians = 32 000 and 98 000, respectively; Tables 1 and 2).

In situ hybridization vRNA patterns in secondary lymphoid tissues in chronically SIV-infected RMs. In situ hybridization signal at (A) low magnification and (B) high magnification within the secondary lymphoid tissue shows 2 distinct and distinguishable patterns: (1) FDC-trapped virions showing a typical “lattice-like” diffuse vRNA pattern, and (2) productively infected vRNA+ T cells showing a strong intense spherical staining pattern. Follicles are outlined in red. Red arrows indicate productively infected SIV vRNA+ cells. Scale bars represent 50 μm.

In situ hybridization vRNA patterns in secondary lymphoid tissues in chronically SIV-infected RMs. In situ hybridization signal at (A) low magnification and (B) high magnification within the secondary lymphoid tissue shows 2 distinct and distinguishable patterns: (1) FDC-trapped virions showing a typical “lattice-like” diffuse vRNA pattern, and (2) productively infected vRNA+ T cells showing a strong intense spherical staining pattern. Follicles are outlined in red. Red arrows indicate productively infected SIV vRNA+ cells. Scale bars represent 50 μm.

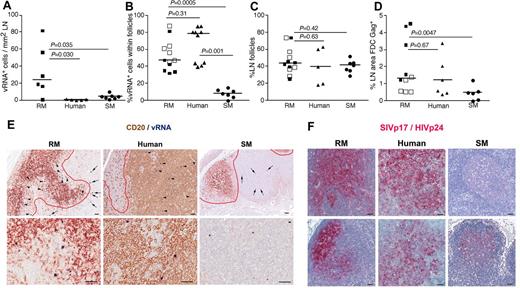

LN anatomic distribution of productively infected cells in RMs, humans, and SMs. (A) Quantitation of the number of SIV/HIV vRNA+ cells/mm2 in LNs of chronically infected RMs, humans, and SMs. (B) Frequency of SIV/HIV vRNA+ cells located within B-cell follicles in LNs of chronically infected RMs, humans, and SMs. (C) The percentage of LN area that consists of B-cell follicles. (D) The percentage LN area of Gag+ (SIVp17+ or HIVp24+) FDCs in chronically infected RMs, humans, and SMs. (E) Combination SIV/HIV in situ hybridization and CD20 IHC showing the relative frequency of SIV/HIV vRNA+ cells located within B-cell follicles (arrowheads) and in the extrafollicular T-cell zone (arrows) in a representative RM, human, and SM at low magnification (top panels) and high magnification (bottom panel). Scale bars represent 50 μm. (F) SIVp17/HIVp24 Gag IHC showing the relative amount of FDC trapped SIV/HIV from 2 chronically infected RMs, humans and SMs. Note the dramatic variability in FDC trapping in SM compared with RM and human. Scale bars represent 50 μm. Horizontal lines represent the median. P values are based on the Mann-Whitney test.

LN anatomic distribution of productively infected cells in RMs, humans, and SMs. (A) Quantitation of the number of SIV/HIV vRNA+ cells/mm2 in LNs of chronically infected RMs, humans, and SMs. (B) Frequency of SIV/HIV vRNA+ cells located within B-cell follicles in LNs of chronically infected RMs, humans, and SMs. (C) The percentage of LN area that consists of B-cell follicles. (D) The percentage LN area of Gag+ (SIVp17+ or HIVp24+) FDCs in chronically infected RMs, humans, and SMs. (E) Combination SIV/HIV in situ hybridization and CD20 IHC showing the relative frequency of SIV/HIV vRNA+ cells located within B-cell follicles (arrowheads) and in the extrafollicular T-cell zone (arrows) in a representative RM, human, and SM at low magnification (top panels) and high magnification (bottom panel). Scale bars represent 50 μm. (F) SIVp17/HIVp24 Gag IHC showing the relative amount of FDC trapped SIV/HIV from 2 chronically infected RMs, humans and SMs. Note the dramatic variability in FDC trapping in SM compared with RM and human. Scale bars represent 50 μm. Horizontal lines represent the median. P values are based on the Mann-Whitney test.

Moreover, comparison of the SIV vRNA+ cells in LNs of SIV-infected RMs and SMs revealed that not only were the numbers of SIV+ cells lower in SIV-infected SMs, but the localization of SIV+ cells within the LNs appeared to be different between RMs and SMs. In chronically SIV-infected RMs, ∼ 50% of the virus-producing SIV+ cells within the LNs were located within B-cell follicles, defined morphologically by CD20 staining, whereas only ∼ 10% of the SIV+ cells in chronically SIV-infected SM were within lymphoid follicles (P = .0005, Figure 3B-E). Importantly, even though HIV-infected persons had lower numbers of infected cells within LNs compared with SIV-infected RMs and similar numbers to SMs, the localization and proportion of infected cells within the lymphoid tissue anatomic compartments (ie, within and outside of B-cell follicles) were similar between humans and RM, with both having a majority of the productively infected cells located within B-cell follicles (average, 54.70% ± 17.84% for RMs and 76.0% ± 7.33% for humans; Figure 3B). In striking contrast, SMs had on average only 7.55% ± 5.24% of the productively infected cells located within B-cell follicles (Figure 3B). Importantly, the differences between anatomic localization of productively infected cells within LNs of RMs and humans and SMs were not attributable to SIV-infected RMs or HIV-infected humans having a greater proportion of B-cell follicles per LN area compared with SIV-infected SMs (Figure 3C). Although the exact reasons for the differential localization and number of productively infected vRNA+ cells in lymphoid tissues from RMs and humans compared with SMs is unknown, the increased frequency of productively infected cells within B-cell follicles of LNs in SIV-infected RMs and HIV-infected humans may be related to the increased trapping of SIV/HIV by follicular FDCs in RMs and humans compared with SMs (Figure 3D,F).

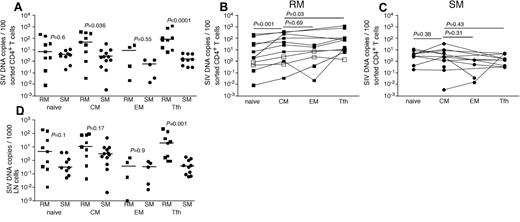

Infection frequencies of LN CD4+ T-cell subsets

Given the clearly higher numbers of productively infected cells in LNs of RMs compared with SMs and the differential anatomic distribution of productively infected vRNA+ cells seen for RMs and humans compared with SMs, we next sought to further characterize the infected cells in LNs. We used flow cytometric cell sorting to separate CD4+ T cells from LNMCs from RMs and SMs into naive (CD28dullCCR7+CD95−), TCM (CD95+CCR7+), TEM (CD95dullCCR7−PD1+ICOSdullCTLA4−), and T follicular helper (TFH, CD95+PD1−ICOS+CCR7−CTLA4+) subsets. We specifically sorted the TFH CD4+ T cells given their proximity to FDCs where we found high levels of trapped virions in LNs of SIV-infected RM (Figure 3B,F). Comparing LN samples from SIV-infected RMs and SIV-infected SMs, we found higher frequencies of SIV-infected TCM and TFH CD4+ T cells in RMs but comparable frequencies of infection of naive and TEM memory CD4+ T cell (Figure 4). Among the LN CD4+ T-cell subsets we examined in RMs, CD4+ TCM cells were more frequently infected than naive CD4+ T cells (Figure 4B), similar to the pattern we observed in peripheral blood (Figure 1B); however, TCM and TEM CD4+ T cells were infected at similar frequencies in LNs (Figure 4B). Among CD4+ T-cell subsets within RM LNs, TFH cells were consistently more frequently infected than any other CD4+ T-cell subset (P = .03 compared with infection of CD4+ TCM cells), and TFH cells were 55-fold more frequently infected in RMs than SMs, consistent with our in situ hybridization evaluation (Figure 4B). Although TCM cells were infected 15-fold more frequently in RMs compared with SMs, in SIVsmm-infected SMs, we found no differences between infection frequencies of the different subsets of LN-resident CD4+ T cells (Figure 3C). Indeed, TFH cells in LNs of SIVsmm-infected SMs were infected at frequencies similar to other LN-resident CD4+ T cells.

SIV infection of CD4+ T-cell subsets in LNs of RMs and SMs. Naive (CD28dull,CCR7+CD95−), TCM (CCR7+CD95+), TEM (CCR7−CD95+), and TFH (CCR7−PD-1+ICOS+CTLA-4+CD95+) CD4+ T cells were flow cytometrically sorted from LNs of SIVsmmE543-infected RMs (■), SIVmac239-infected RMs (□), and SIVsmm-infected SMs (●), and infection levels of individual subsets were determined by quantitative PCR. Infection frequencies of individual subsets are compared between RMs and SMs (A). Infection frequencies of different subsets are compared within RMs (B) and SMs (C). Numbers of CD4+ T cells in each subset containing viral DNA per 1000 total LNMCs. Horizontal lines represent the median. P values are based on the Mann-Whitney test (A,D) or the Wilcoxon matched pairs test (B-C).

SIV infection of CD4+ T-cell subsets in LNs of RMs and SMs. Naive (CD28dull,CCR7+CD95−), TCM (CCR7+CD95+), TEM (CCR7−CD95+), and TFH (CCR7−PD-1+ICOS+CTLA-4+CD95+) CD4+ T cells were flow cytometrically sorted from LNs of SIVsmmE543-infected RMs (■), SIVmac239-infected RMs (□), and SIVsmm-infected SMs (●), and infection levels of individual subsets were determined by quantitative PCR. Infection frequencies of individual subsets are compared between RMs and SMs (A). Infection frequencies of different subsets are compared within RMs (B) and SMs (C). Numbers of CD4+ T cells in each subset containing viral DNA per 1000 total LNMCs. Horizontal lines represent the median. P values are based on the Mann-Whitney test (A,D) or the Wilcoxon matched pairs test (B-C).

We next assessed the total number of infected cells belonging to each CD4+ T-cell subset per 1000 LNMCs in RMs and SMs. Even though CD4+ T cells are progressively depleted from lymphoid tissues of SIV-infected RM (hence, RM have fewer total numbers of CD4+ T cells), there were as many SIV-infected naive, TCM, and TEM CD4+ T cells per 1000 LNMCs in SIV-infected RM as in SIV-infected SMs (Figure 4D). Consistent with the increased frequency of SIV infection of TFH cells in RMs compared with SMs, there were higher numbers of SIV-infected TFH cells/1000 LN cells in RMs (Figure 4D). Although among CD4+ T-cell subsets, TFH cells were infected at the highest frequency in SIV-infected RMs (Figure 4), numbers of CD4+ TFH were actually increased in chronically SIV-infected RMs compared with SIV-uninfected RMs (Figure 5A).

Phenotype of LN-resident CD4+ T-cell subsets of RMs and SMs. Frequencies of TFH (CCR7−PD-1+ICOS+CTLA-4+CD95+) CD4+ T cells among memory (CD28brightCD95+) T cells was determined in SIV-uninfected RMs (▵), SIVsmmE543-infected RMs (■), SIVmac239-infected RMs (□), SIV-uninfected SMs (○), and SIVsmm-infected SMs (●) by flow cytometry (A). Expression of Ki-67 (B) and CCR5 (C) by subsets of LN CD4+ T cells. Horizontal lines represent the median. P values are based on the Mann-Whitney test.

Phenotype of LN-resident CD4+ T-cell subsets of RMs and SMs. Frequencies of TFH (CCR7−PD-1+ICOS+CTLA-4+CD95+) CD4+ T cells among memory (CD28brightCD95+) T cells was determined in SIV-uninfected RMs (▵), SIVsmmE543-infected RMs (■), SIVmac239-infected RMs (□), SIV-uninfected SMs (○), and SIVsmm-infected SMs (●) by flow cytometry (A). Expression of Ki-67 (B) and CCR5 (C) by subsets of LN CD4+ T cells. Horizontal lines represent the median. P values are based on the Mann-Whitney test.

To understand potential mechanisms underlying the observed high frequency of infection of TFH CD4+ T cells in SIV-infected RMs, we performed phenotypic analysis of TFH cells in LNs of SIV-infected and uninfected RMs and SMs (Figure 5B-C). Specifically, we determined whether or not TFH cells may be more prone to SIV infection in vivo because of higher proliferation (based on expression of Ki-67, Figure 5B) or because of higher expression of CCR5 (Figure 5C). Whether we compared TFH cells with non-TFH cells in SIV-infected or uninfected SMs or RMs, we did not observe evidence of increased proliferation or expression of CCR5 by TFH cells. Indeed, in SIV-infected RMs and SMs, the TFH cells showed lower levels of Ki-67 expression than non-TFH memory CD4+ T cells (Figure 5B), and fewer of the TFH cells expressed CCR5 (Figure 5C).

Discussion

The mechanisms underlying the benign nature of SIV infection of natural hosts as opposed to the progressive and ultimately fatal nature of SIV infection in the experimental RM host and in HIV-infected humans are probably complex and multifactorial. Although much recent research has focused on the contributions of the absence of chronic immune activation and the relatively lower levels of CD4+ TCM infection34 seen in SIV infection of natural hosts to the lack of disease, many aspects of the nonpathogenic phenotype of SIV-infected SM remain poorly understood. Furthermore, the complexity of understanding the potential role of differential in vivo viral dynamics in natural hosts that do not progress to disease is highlighted by several inconsistent findings from early studies and differences in viral replication kinetics between natural host species.35-39

Here we have used complementary approaches (ie, in situ hybridization, with immunohistochemistry, flow cytometric sorting, and quantitative, real-time PCR) to characterize the frequencies of infected CD4+ T-cell subsets in blood and LNs of chronically infected RM, humans and SM documenting differences in the frequency and subset distribution of infected cells between the SIV natural host (SM) and experimental SIV pathogenic host (RM) and pathogenic HIV infection in humans. Specifically, we demonstrate: (1) the frequency of SIV-infected CD4+ TCM cells is ∼ 15- to 30-fold higher in RMs compared with SMs in LNs and PBMCs, respectively; (2) the frequency of SIV-infected CD4+ TFH cells is dramatically higher in RMs compared with SMs; (3) increased infection of the TFH cells in RMs and humans is associated with increased viral trapping by FDCs; and (4) LN viral burden is substantially greater in RMs and humans compared with SMs. These results suggest that one of the mechanisms contributing to the nonprogressive nature of natural SIV infection may involve viral infection in SMs of CD4+ T-cell subsets, which are more dispensable for maintaining immunocompetence in contrast to infection of other CD4+ T-cell subsets that may contribute to progressive pathogenic infection in RMs and humans.

Progression to AIDS in HIV/SIV infections is inevitably linked to a compromised immune system resulting from depletion of CD4+ T cells. Given the numerous functional subsets of memory CD4+ T cells, development of AIDS in progressively infected persons, manifested clinically by opportunistic infections, probably is multifactorial, involving depletion and/or functional compromise of multiple cellular immune subsets. Indeed, progressive HIV/SIV infection has been associated with decreased functionality of memory Th1 CD4+ T cells40 and CD8+ T cells,41 decreased frequencies of mucosal Th17 CD4+ T cells,42-44 and alterations in the frequencies of memory Treg CD4+ T cells.44-46 Humoral immunity, aspects of which depend on help provided by CD4+ T cells, is also dysfunctional in progressively infected persons.47-49 The importance of these immunologic phenomena in leading to an immunocompromised state is highlighted by their absence in chronically SIV-infected natural hosts for SIV, even though natural hosts for SIV can maintain high levels of viral replication in the chronic phase of infection. The mechanisms that allow natural hosts to maintain high levels of viral replication without developing progressive immunodeficiency and ultimately dying of opportunistic consequences of immunodeficiency are of critical importance to understand the progression to an immunocompromised state in HIV/SIV-infected non-natural hosts.3

Our data are consistent with several studies suggesting that one of the mechanisms underlying the nonprogressive nature of SIV infection in natural hosts is the selective targeting of the virus toward lymphocyte subsets that are relatively more dispensable for the immune system.19,21,50 Indeed, consistent with a previous report, we find that, during chronic infection with SIVsmmE543 and SIVmac239, there is frequent infection of CD4+ TCM cells in peripheral blood of RMs, whereas CD4+ TEM cells are infrequently infected by comparison. In SMs, we found that CD4+ TCM cells were not infected at increased frequency by SIVsmm compared with CD4+ TEM cells in peripheral blood. Given that central memory CD4+ T cells appear to be a critical source of long-term memory, are important for homeostatic maintenance of the memory CD4+ T-cell subset,17 and (based on the markers we use to identify CD4+ TCM cells) contain the newly identified stem cell memory subset (CD45RA+CD28+CD27+CCR7+CD62L+CD127+CD45RO−CD95+),51 sparing CD4+ TCM cells from infection within SMs may be an important factor for the nonprogressive nature of the infection.

Although the mechanism underlying the differential infection of CD4+ TEM cells in SMs compared with RMs appears to involve altered expression patterns of the HIV/SIV coreceptor CCR5 by CD4+ TEM cells,21 this does not appear to explain the differential infection frequencies of TFH cells we observe in RMs compared with SMs. Our data demonstrating increased frequencies of infection of TFH in LNs from RMs and humans compared with SMs are consistent with previous findings by Hufert et al52 and Folkvord et al,27 which found that germinal center T cells from HIV-infected subjects demonstrated an ∼ 10-fold higher frequency of HIV infection than other CD4+ lymphocytes and that these same cells possessed a higher rate of virus expression than other CD4+ T cells. Given that FDCs in humans and RMs trap infectious virions in vivo and that FDCs have been demonstrated to contribute important signals to the immunologic functions of germinal centers,30,53 the B-cell follicles appear to represent an ideal microenvironment that brings together infectious virus and highly susceptible target cells in the form of TFH cells in progressive lentiviral infections.

TFH cells are of particular importance for normal humoral immune responses. Indeed, this subset of germinal center resident CD4+ T cells provides signals that lead to memory B-cell development, antibody affinity maturation, and isotype switching.54 Hence, the lower frequency of infection of TFH cells in SM could contribute to the preserved B-cell responses and an overall immunocompetent state characteristic of SIV infection in natural hosts. The lower frequency of infection of TFH cells in SM appears to be associated with very limited FDC trapping of SIV-immune complexes in the follicles of LN, which is in line with earlier studies that did not detect FDC-trapped SIV in SMs or AGMs.35,37 The differential level of FDC-viral trapping and infected TFH cells in RMs and humans may also be associated with the relative activation status of the follicular environment and the immunopathology that is associated with this microenvironment in pathogenic lentiviral infections. Even though we did not see differences in the total area of the LN that consisted of B-cell follicles, both RMs and humans had abundant evidence of hyperplastic irregularly shaped follicles, whereas SMs had normal follicular morphology and structure. The mechanism underlying decreased FDC trapping of virions could be multifaceted and could involve lower viral replication in B-cell follicles of LN, altered expression of Fc or complement receptors by SM FDCs, and/or increased clearance of immunocomplexes containing SIV in SMs.

Taken together, our data suggest that one of the key mechanisms by which natural hosts for SIV avoid disease progression involves differential rates of infection of different key subsets of CD4+ T cells. In SMs, we document infection of CD4+ TEM cells and lack of FDC trapping of SIV immune complexes in SMs, associated with lower frequencies of infection of TFH cells. That central memory CD4+ T cells and TFH cells are less frequently infected in SMs than in RMs or humans suggests that relative preservation of these critical CD4+ T-cell subsets may contribute to maintenance of immunologic competence. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying this differential viral targeting of distinct cellular subsets in SM could lead to novel therapeutic interventions to alter cellular substrates for viral replication in non-natural hosts for HIV/SIV and improve the prognosis of progressively, HIV-infected persons.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Pathology/Histotechnology Laboratory at the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD, for expert support, and the Cleveland Immunopathogenesis Consortium (CLIC/BBC) for advice and helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Intramural National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health program, and the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (contract HHSN261200800001E and R01 AI-084836, M.P.).

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: J.M.B. and J.D.E. conceived and designed the study, provided material support, acquired and interpreted data, supervised the study, and wrote manuscript; C.V., B.T., and X.P.H. acquired data; E.C., M.P., and G.S. provided critical material support, interpreted data, and assisted with manuscript revisions; and J.D.L. interpreted data and assisted with manuscript revisions.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jason M. Brenchley, Program in Barrier Immunity and Repair and Immunopathogenesis Unit, Laboratory of Molecular Microbiology, NIAID, NIH, 4 Center Dr, Rm 201, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: jbrenchl@mail.nih.gov; and Jacob D. Estes, AIDS and Cancer Virus Program, SAIC-Frederick Inc, Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, 1050 Boyles St, Bldg 535, Rm 411, Frederick, MD 21702; e-mail: estesj@mail.nih.gov.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal