Abstract

In recent decades, attention has focused on reducing long-term, treatment-related morbidity and mortality in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). In the present study, we looked for trends in relative survival for all patients diagnosed with HL in Sweden from 1973-2009 (N = 6949; 3985 men and 2964 women; median age, 45 years) and followed up for death until the end of 2010. Patients were categorized into 6 age groups and 5 calendar periods (1973-1979, 1980-1986, 1987-1994, 1994-2000, and 2001-2009). Relative survival improved in all age groups, with the greatest improvement in patients 51-65 years of age (P < .0005). A plateau in relative survival was observed in patients below 65 years of age during the last calendar period, suggesting a reduced long-term, treatment-related mortality. The 10-year relative survival for patients diagnosed in 2000-2009 was 0.95, 0.96, 0.93, 0.80, and 0.44 for the age groups 0-18, 19-35, 36-50, 51-65, and 66-80, respectively. Therefore, despite progress, age at diagnosis remains an important prognostic factor (P < .0005). Advances in therapy for patients with limited and advanced-stage HL have contributed to an increasing cure rate. In addition, our findings support that long-term mortality of HL therapy has decreased. Elderly HL patients still do poorly, and targeted treatment options associated with fewer side effects will advance the clinical HL field.

Introduction

Over the past 40 years, major advances have been made in the management of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). These include the introduction of more accurate radiotherapy, effective multiagent chemotherapy, immunotherapy, improved staging procedures, and important developments in supportive measures for myelosuppression and infectious and other complications.1 Therefore, HL has gone from being an invariably fatal disorder to one of the few malignancies that are now highly curable. This is particularly true for patients with early-stage disease, but today disease control rates also exceed 70% in patients presenting with high-risk features.2 This therapeutic success has unfortunately been darkened by elevated risks of secondary primary cancers, cardiovascular disease (CVD), cerebrovascular disease, and infections in long-term HL survivors.3-16

CVD has been reported to be the most important cause of excess mortality after HL and second malignancies.10,11,13,14 During the last 2-3 decades, treatment strategies have been and are being adapted based on increased knowledge of treatment-related morbidity and mortality. Awaiting novel and less toxic targeted therapies of HL, the largest potential for improving survival and health-related quality of life in long-term survivors17 is by reducing the excess morbidity and mortality from causes other than HL. To evaluate progress in long-term outcome, we studied patient survival among all 6949 HL patients diagnosed in Sweden between 1973 and 2009 and followed up for death to the end of 2010. Our aim was to assess trends in patient survival and long-term excess mortality in the entire population during this 37-year period starting when curative treatment principles were well-established.

Methods

Central registers and patients

Information regarding patients diagnosed with a malignant disorder in Sweden is reported to a population-based nationwide Swedish Cancer Register that was established in 1958. The register contains information on diagnosis, sex, date of birth, date of diagnosis, and the hospital where the diagnosis was made,18,19 but does not contain detailed clinical information such as symptoms, routine laboratory tests, treatment, or comorbidities.

In Sweden, every physician and pathologist/cytologist is obliged by law to report each occurrence of cancer to the registry. All deaths are recorded in the nationwide causes of death register. Each person in Sweden is given a unique national registration number used to index all health registers used in this study. We obtained aggregate-level information on the total number of allogeneic and autologous stem cell transplantations (SCTs) performed in HL patients in Sweden during the study period from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) register, which was established in 1974. The Swedish Cancer Registry classifies all cases using International Classification of Diseases Version 7 (ICD-7). We identified all patients diagnosed with HL (ICD-7 201) between January 1, 1973 and December 31, 2009 in the Swedish Cancer Register. For the 16 individuals registered as having multiple primary HL, we only considered the first diagnosis. We did not otherwise exclude patients on the basis of previous cancer diagnoses. HL patients diagnosed incidentally at autopsy or whose diagnosis was not verified microscopically were excluded from the analyses. In a re-evaluation of 251 tumor biopsies from patients ≥ 15 years of age diagnosed with HL in Sweden from 1985-1994, the diagnosis of HL was confirmed in 89% of the tumors.20

All patients were followed from the date of diagnosis until death, emigration, or end of follow-up (December 31, 2010), whichever occurred first. The choice to include patients from 1973 was because, by then, the Swedish Cancer Register had reached a high coverage18,21 and because treatment with MOPP (mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone) had been introduced as standard induction treatment for most patients with advanced disease judged eligible for aggressive treatment.22,23 The study was approved by the Stockholm Ethics Review Board.

Treatment principles of HL during the study period

During the entire study period (1973-2009), treatment principles for HL in Sweden have followed those of the international Western medical community. In the beginning of this period, most patients with limited disease (stages I-IIA, sometimes stages IIB/IIIA) received radiotherapy (mantle/para-aortic/inverted Y field/total nodal irradiation). After the report by de Vita et al,22 MOPP chemotherapy was introduced for patients with advanced disease (stages IIIB-IV). The Stockholm Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group was established in 197323 and national Swedish treatment recommendations for HL were introduced in 1985 and have been updated over the years.24-26 In 1975, the successful use of the combination ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) was reported,27 and since the early 1980s, a variety of chemotherapy combinations other than conventional MOPP, including ABVD, MOPP/ABVD, MOPP/ABV (for younger patients), and ChLVPP (chlorambucil, vinblastine, procarbazine, prednisolone), LVPP/OEPA (chlorambucil, vinblastine, procarbazine, vincristine, etoposide, prednisone, doxorubicin), and CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; mostly elderly patients) were used in previously untreated patients with stage IIB-IV disease.28-32 Since the 1980s patients with advanced disease reaching a complete remission after 2 cycles traditionally received a total of 6 cycles of chemotherapy.29,33 Very few HL patients with advanced disease and high-risk features received BEACOPP chemotherapy (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone) during the study period.2,34 Combined modality treatment for patients with limited-stage disease became increasingly common during the 1980s.35 Irradiation for previously bulky disease in patients with stage III-IV disease was also widespread during the 1980s and 1990s. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous SCTs for patients with refractory/relapsing disease was started in the mid-1980s with BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) as the prevailing high-dose regimen.36,37 Staging during the period 1972-1988 often included laparotomy and splenectomy.38,39 The management of frail elderly patients has been more varied.32,40,41 During recent years, treatment of HL has been increasingly influenced by the goal of minimizing late therapy-related complications. Therefore, a more tailored treatment has become an important concept to offer the best chance of cure with reduced risk of toxicity. As an example, a common Nordic protocol for patients with stage I-IIA disease based on risk-adjusted treatment was initiated in 1999.42

Survival analysis

Relative survival ratios (RSRs) were computed as measures of HL survival.43,44 An important advantage of using relative survival is that it does not rely on the accurate classification of cause of death. Instead, it provides a measure of total excess mortality associated with a diagnosis of HL irrespective of whether the excess mortality is directly or indirectly because of the cancer. As such, the RSR captures excess mortality because of, for example, treatment-related CVD or secondary malignancies, which is not possible when using cause-specific survival. The RSR is defined as the observed survival in the patient group (where all deaths are considered as events) divided by the expected survival of a comparable group from the general population free from the cancer in question. One-year, 5-year, and 10-year RSRs can be interpreted as the proportion of HL patients who survive 1, 5, and 10 years, respectively, in the hypothetical scenario where HL is the only possible cause of death. Expected survival was estimated using the Ederer II method45 from Swedish population life tables stratified by age, sex, and calendar period. RSRs were calculated for patients diagnosed during 5 calendar periods, 1973-1979, 1980-1986, 1987-1994, 1994-2000, and 2001-2009, and 6 age categories, 0-18, 19-35, 36-50, 51-65, 66-80, and ≥ 80 years. Poisson regression was used to model excess mortality46 to estimate the effects of the factors described above while controlling for potential confounding factors. The parameter estimates from this model are interpreted as excess mortality ratios; an excess mortality ratio of 1.5, for example, for males/females indicates that males experience 50% higher excess mortality (the difference between observed and expected mortality) than females. All calculations were performed using Stata Version 11.2 software (StataCorp).

Results

A total of 6949 HL patients, 3985 men (57%) and 2964 women (43%) with a median age of 45 years (range, 2-99 years) were included in the study (Table 1). The male predominance was more marked in early calendar periods, but persisted throughout the study period (Table 1 and supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The age-standardized overall incidence rate decreased until the early to mid-1990s and then remained essentially stable (supplemental Figure 1). The decline in incidence is driven primarily by the pattern among males 50 years of age or older, and there is evidence of a slight increase in incidence among children and younger adults (≤ 34 years; supplemental Figures 2 and 3).

Characteristics of patients diagnosed with HL in Sweden from 1973 to 2009

| . | 1973-1979 . | 1980-1986 . | 1987-1993 . | 1994-2000 . | 2001-2009 . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 1006 (61) | 729 (57) | 702 (57) | 684 (57) | 864 (55) | 3985 (57) |

| Female | 643 (39) | 558 (43) | 534 (43) | 512 (43) | 717 (45) | 2964 (43) |

| Total | 1649 | 1287 | 1236 | 1196 | 1581 | 6949 |

| Age at diagnosis, y, n (%) | ||||||

| 0-18 | 92 (5.6) | 98 (7.6) | 146 (11.8) | 146 (12.2) | 172 (10.9) | 654 (9.4) |

| 19-35 | 362 (21.9) | 338 (26.3) | 374 (30.3) | 441 (36.9) | 557 (35.2) | 2072 (29.8) |

| 36-50 | 243 (14.7) | 224 (17.4) | 220 (17.8) | 183 (15.3) | 253 (16.0) | 1123 (16.2) |

| 51-65 | 389 (23.6) | 230 (17.9) | 189 (15.3) | 173 (14.5) | 272 (17.2) | 1253 (18.0) |

| 66-80 | 463 (28.1) | 318 (24.7) | 248 (20.1) | 199 (16.6) | 246 (15.6) | 1474 (21.2) |

| 81 or older | 100 (6.1) | 79 (6.1) | 59 (4.8) | 54 (4.5) | 81 (5.1) | 373 (5.4) |

| Median age, y | 57 | 49 | 41 | 36 | 39 | 45 |

| SCTs, n | ||||||

| Allogeneic | NI | 0* | 0† | 1 | 37 | 38 |

| Autologous | NI | 2* | 49† | 96 | 163 | 310 |

| . | 1973-1979 . | 1980-1986 . | 1987-1993 . | 1994-2000 . | 2001-2009 . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 1006 (61) | 729 (57) | 702 (57) | 684 (57) | 864 (55) | 3985 (57) |

| Female | 643 (39) | 558 (43) | 534 (43) | 512 (43) | 717 (45) | 2964 (43) |

| Total | 1649 | 1287 | 1236 | 1196 | 1581 | 6949 |

| Age at diagnosis, y, n (%) | ||||||

| 0-18 | 92 (5.6) | 98 (7.6) | 146 (11.8) | 146 (12.2) | 172 (10.9) | 654 (9.4) |

| 19-35 | 362 (21.9) | 338 (26.3) | 374 (30.3) | 441 (36.9) | 557 (35.2) | 2072 (29.8) |

| 36-50 | 243 (14.7) | 224 (17.4) | 220 (17.8) | 183 (15.3) | 253 (16.0) | 1123 (16.2) |

| 51-65 | 389 (23.6) | 230 (17.9) | 189 (15.3) | 173 (14.5) | 272 (17.2) | 1253 (18.0) |

| 66-80 | 463 (28.1) | 318 (24.7) | 248 (20.1) | 199 (16.6) | 246 (15.6) | 1474 (21.2) |

| 81 or older | 100 (6.1) | 79 (6.1) | 59 (4.8) | 54 (4.5) | 81 (5.1) | 373 (5.4) |

| Median age, y | 57 | 49 | 41 | 36 | 39 | 45 |

| SCTs, n | ||||||

| Allogeneic | NI | 0* | 0† | 1 | 37 | 38 |

| Autologous | NI | 2* | 49† | 96 | 163 | 310 |

NI indicates no information available.

No information was available for 1980-1985.

No information was available for 1987.

A total of 348 SCTs in HL, 38 allogeneic and 310 autologous, were reported to the EBMT registry during the study period. Of these, more than half (57%) were carried out during the last calendar period, with autologous SCT dominating (Table 1).

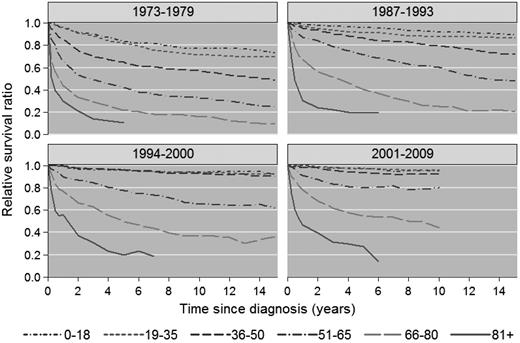

There was significant improvement in 1-, 5-, and 10-year RSR across the study period in all age groups (Figure 1A-C), although the most pronounced improvements in 5- and 10-year RSR were seen among patients 36-50, 51-65, and 66-80 years of age, respectively, and was most conspicuous among patients 51-65 years of age (Figure 1B-C). This is also illustrated in Figures 2 and 3, which show the cumulative relative survival stratified by age at diagnosis and calendar period. During the last calendar period, there seems to be a plateau in relative survival after 5 years in patients up to 65 years of age. A plateau in the cumulative relative survival curve indicates that the patients experience the same mortality as the general population—that is, that there is no evidence of HL-related excess mortality.

Relative survival of HL patients in Sweden diagnosed from 1973-2009. Estimates of 1-year (A), 5-year (B), and 10-year (C) relative survival among HL patients stratified by age category and calendar period of diagnosis.

Relative survival of HL patients in Sweden diagnosed from 1973-2009. Estimates of 1-year (A), 5-year (B), and 10-year (C) relative survival among HL patients stratified by age category and calendar period of diagnosis.

Cumulative relative survival among HL patients in Sweden stratified by age at diagnosis and calendar period of diagnosis.

Cumulative relative survival among HL patients in Sweden stratified by age at diagnosis and calendar period of diagnosis.

Cumulative relative survival among HL patients in Sweden stratified by calendar period of diagnosis and age at diagnosis. Data for 1980-1986 are not shown.

Cumulative relative survival among HL patients in Sweden stratified by calendar period of diagnosis and age at diagnosis. Data for 1980-1986 are not shown.

Excess mortality rates during the first 10 years after diagnosis were significantly lower in later calendar periods (P < .0005) and in younger patients (P < .0005; Table 2). Females had a 19% lower excess mortality compared with males during the first 10 years after diagnosis (P < .0005; Table 2).

Excess mortality rate ratios and 95% CIs during the first 10 years after HL diagnosis by calendar period, sex, region, and age at diagnosis

| . | Excess mortality rate ratio . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|

| Calendar period of HL diagnosis (P < .0005) | ||

| 1973-1979 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 1980-1986 | 0.67 | (0.59-0.74) |

| 1987-1994 | 0.49 | (0.43-0.55) |

| 1995-2000 | 0.32 | (0.28-0.38) |

| 2001-2009 | 0.28 | (0.24-0.33) |

| Sex (P < .0005) | ||

| Male | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Female | 0.81 | (0.74-0.88) |

| Health-care region of diagnosis (P = .18) | ||

| Stockholm/Gotland | 0.92 | (0.82-1.04) |

| Other | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Age at HL diagnosis, y (P < .0005) | ||

| 0-18 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 19-35 | 1.36 | (1.01-1.83) |

| 36-50 | 2.41 | (1.79-3.24) |

| 51-65 | 6.13 | (4.63-8.12) |

| 65-80 | 13.10 | (9.94-17.28) |

| ≥ 80 | 25.17 | (20.13-36.66) |

| . | Excess mortality rate ratio . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|

| Calendar period of HL diagnosis (P < .0005) | ||

| 1973-1979 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 1980-1986 | 0.67 | (0.59-0.74) |

| 1987-1994 | 0.49 | (0.43-0.55) |

| 1995-2000 | 0.32 | (0.28-0.38) |

| 2001-2009 | 0.28 | (0.24-0.33) |

| Sex (P < .0005) | ||

| Male | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Female | 0.81 | (0.74-0.88) |

| Health-care region of diagnosis (P = .18) | ||

| Stockholm/Gotland | 0.92 | (0.82-1.04) |

| Other | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Age at HL diagnosis, y (P < .0005) | ||

| 0-18 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 19-35 | 1.36 | (1.01-1.83) |

| 36-50 | 2.41 | (1.79-3.24) |

| 51-65 | 6.13 | (4.63-8.12) |

| 65-80 | 13.10 | (9.94-17.28) |

| ≥ 80 | 25.17 | (20.13-36.66) |

All variables are simultaneously adjusted for all other variables in the table. P values are provided for the likelihood ratio test comparing the model without the specific factor with the model with all factors.

Discussion

Based on the analysis of this large nationwide cohort of 6949 HL patients, there has been a significant gradual improvement in prognosis over the last 3 decades. The better outcome was observed in 1-, 5-, and 10-year relative survival, and was most conspicuous in patients 36-80 years of age at diagnosis. However, 5- and 10-year relative survival improved significantly in all age categories except in the very old (> 80 years). Although the age-related differences in survival are decreasing, age at diagnosis remains a strong predictor of prognosis.30,40,47 A recent analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database of the United States National Cancer Institute showed a particular improvement in 10-year relative survival of HL patients 45-59 years of age and those 60 years of age and older.48 This is consistent with our findings, although we also observed improvements in patients 65-80 years of age at diagnosis.

In the 4 youngest age categories (up to 65 years) a plateau in relative survival was observed after 5 years during the last calendar period, indicating that patients surviving 5 years experience the same mortality as the general population and suggesting that long-term treatment mortality has decreased drastically. In the SEER-based study, relative survival did not reach a clear plateau for any age group.48 Even though long-term follow-up information was not available for the majority of our patients in the last calendar period, we believe that these findings are important. The results reflect an improved tumor control, but also confirm that the goal to reduce late therapy–related fatal complications has been successful. Therefore, a more tailored treatment has become an important concept to offer the best chance of cure with reduced risk of toxicity, particularly in younger patients. The introduction of combined modality treatment in patients with localized disease, which has allowed reduced irradiation fields and abbreviated chemotherapy35 and ABVD chemotherapy for advanced disease,28 has probably contributed the most to this improvement. However, even if the results of the present study favor the concept that lower doses of radiation will reduce the risk of late fatal toxicities, we still lack long-term detailed follow-up data.49 Moreover, high-dose chemotherapy with autologous SCT for patients with refractory/relapsing disease was an important addition to the therapeutic armamentarium.36

During the study period of 1973-2009, the incidence of HL decreased significantly in people more than 40 years of age, and this pattern was more pronounced in men. This is also reflected in a decreasing median age of patients in our study. Although the reasons for this decline are obscure, Hjalgrim et al noticed a significantly decreased incidence of non-nodular sclerosis subtypes and unspecified HL in the age group of 40 years and above during 1978-1997, and suggested that changes in diagnostic procedures may have contributed to the observed decline.50 Concomitantly, there was a smaller slow but significant increase in incidence among adolescents and young adults, which was reported to occur primarily for HL of the nodular sclerosis subtype.50 In good agreement with previous observations, the age-adjusted HL incidence was higher in men51 and we also found a significantly better survival for women when adjusted for age and calendar period.30

In the present study, when calculating RSR estimates, we compared survival among all Swedish HL patients with the total Swedish population as a reference group. In contrast, Brenner et al used SEER data for patients diagnosed from 1973-2004 covering a population of about 30 million people and compared HL survival with that of the total United States population.48 Another difference between our study and the study by Brenner et al is that they used a period analysis, whereas in the present study, we used a cohort approach.48 Cohort estimates represent the actual survival experience of a well-defined cohort of patients, which is not the case for period estimates. Although not directly comparable because of minor differences in age categories and calendar period, relative survival appears overall to be somewhat better in the Swedish population during the latest calendar period under study for patients up to 45 years of age at diagnosis. This was also confirmed when, to facilitate a direct comparison, we estimated 5-year relative survival using a period approach (period window 2000-2004) with the same age categories as Brenner et al.48 The estimated 5-year relative survival ratios (with the estimates from Table 2 in Brenner et al48 given in parentheses) were: 15-24 years, 0.95 (0.94); 25-34 years, 0.98 (0.93); 35-44 years, 0.97 (0.89); 45-59 years, 0.86 (0.83); and 60 years and over, 0.59 (0.59). Even if survival of patients aged 60+ is the same in the 2 countries, we believe that the proportion of very elderly is higher in Sweden. For readers interested in predictions of survival for recently diagnosed patients, we present results from a period analysis using the most up-to-date available data (period window 2007-2010) in supplemental Figure 4. There are several potential explanations for the higher survival in Sweden. First, an important difference between the 2 studies relates to the inherent differences in the medical healthcare systems between the United States and Sweden. Sweden has a well-established government-funded public health-care system in which all residents by law are entitled to equal access to health services. Second, patients with HL are almost exclusively diagnosed, treated, and followed clinically by physicians at nonprivate, hospital-based hematology/oncology units. As a consequence, treatment decisions, including autologous (and allogeneic) SCTs, are based solely on patient- and disease-related factors independent of financial considerations. Third, in the mid-1980s, national Swedish guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of HL were introduced and updated on a regular basis. Notwithstanding the better outcome of Swedish patients, an impressive improvement in relative survival over time has clearly been documented in both studies. It is possible that some of the improvements in survival can be explained by changes in disease characteristics (with a more a favorable distribution of prognostic factors in recent years). Detailed information on clinical prognostic factors is not available on a national level for the entire study period, but we obtained data from 2 clinical registers spanning the study period to identify potential changes in disease characteristics. We obtained information from the Stockholm HL group for patients diagnosed in the Stockholm area from 1973-1994 and from the Swedish National Lymphoma Register for all patients diagnosed in Sweden from 2000-2008. We saw no evidence that the distribution of stage or presence of B-cell symptoms changed during the course of the study (supplemental Table 1). There was evidence that the proportion of patients with nodular sclerosing subtype has increased over time, but the trends in subtype are difficult to interpret because of changes in how subtype is classified and improvements in diagnostics (supplemental Table 2).

In the present study, we used a register-based cohort design that ensured a population-based setting and generalization of our findings. We computed RSR estimates as measures of HL survival, which is in contrast to reports on survival from clinical trials. A major advantage of using RSR as the measure of survival is that information on cause of death is not required and the measure captures excess mortality both directly and indirectly because of HL (eg, treatment-related mortality). The crucial assumption in working with RSR estimates is that one can accurately estimate expected survival. For most cancers (including HL), patients are representative of the general population of the same age and sex, so their expected survival can be estimated using general-population survival rates and subsequent estimates of relative survival can be interpreted as a measures of excess mortality because of the cancer.44 In contrast to reports based on patients treated in clinical trials, the large majority of patients in this study (> 95%) were treated in routine clinical practice. Therefore, elderly patients and patients not treated with curative intent were included in the analysis. This study therefore supplies a more complete picture of the survival of HL patients in the population.

Limitations of the present study include lack of clinical data for individual patients and detailed changes in diagnostic practices/accuracy over time. Conversely, it is not likely that the observed improved survival is influenced by an increased access to healthcare and earlier detection of the disease over time (ie, lead-time bias). Most probably, a combination of factors related to diagnostics, staging, and treatment have contributed to the observed improvements in HL survival. In parallel to specific HL treatment strategies that have developed over time, important developments in supportive measures for myelosuppression, infections, and other complications have been introduced. Despite this progress, survival remains substantially lower in elderly patients, especially those above 80 years of age. Many elderly patients are not fit for intensive chemotherapy or radiotherapy because of comorbidities and poor performance status, leading to low complete remission rates and inferior survival.

In summary, in the present study, we found that HL patients younger than 80 years have gained significantly from the developments in management of the disease during a 37-year period. However, age still remains an important predictor of prognosis, which is why innovative agents and procedures suitable for the older patient are needed. More individualized management based on accurate risk stratification will hopefully further improve the outlook for the whole HL patient population. In addition, continued analysis of late effects associated with newer treatment for HL will be imperative for today's and tomorrow's patients.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the EBMT for providing information regarding the SCTs.

This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society (CAN 2009/1203), the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet (SLL 20090201), and the Karolinska Institutet Foundations (2009Fobi0072).

Authorship

Contribution: J.S., C.H., P.W.D., and M.B. wrote the manuscript; C.H., U.A.N., J.S., P.W.D., and M.B. collected the data; C.H. and P.W.D. performed the statistical analyses; P.W.D. and M.B. designed the study; and all authors analyzed the data and read, commented on, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Magnus Björkholm, MD, PhD, Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology, Karolinska University Hospital Solna, SE-171 76 Stockholm, Sweden; e-mail: magnus.bjorkholm@karolinska.se.

References

Author notes

J.S. and C.H. contributed equally to this work.

P.W.D. and M.B. are co–senior authors.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal