BCR-ABL overexpression and stem cell quiescence supposedly contribute to the failure of imatinib mesylate (IM) to eradicate chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). However, BCR-ABL expression levels of persisting precursors and the impact of long-term IM therapy on the clearance of CML from primitive and mature bone marrow compartments are unclear. Here, we have shown that the number of BCR-ABL–positive precursors decreases significantly in all bone marrow compartments during major molecular remission (MMR). More importantly, we were able to demonstrate substantially lower BCR-ABL expression levels in persisting MMR colony-forming units (CFUs) compared with CML CFUs from diagnosis. Critically, lower BCR-ABL levels may indeed cause IM insensitivity, because primary murine bone marrow cells engineered to express low amounts of BCR-ABL were substantially less sensitive to IM than BCR-ABL–overexpressing cells. BCR-ABL overexpression in turn catalyzed the de novo development of point mutations to a greater extent than chemical mutagenesis. Thus, MMR is characterized by the persistence of CML clones with low BCR-ABL expression that may explain their insensitivity to IM and their low propensity to develop IM resistance through kinase point mutations. These findings may have implications for future treatment strategies of residual disease in CML.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a clonal disorder of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) caused by the aberrant expression of the breakpoint cluster region-Abelson murine leukemia (BCR-ABL) fusion protein.1,–3 Imatinib mesylate (IM; Glivec, Novartis Pharma) is a selective inhibitor of BCR-ABL and induces high rates of stable complete cytogenetic remissions (CCyRs) in chronic phase of CML.4,5 However, despite long-term IM therapy, BCR-ABL-mRNA and BCR-ABL–positive CFUs remain detectable during CCyR.4,6,7 Stem cell persistence also is supported by clinical evidence showing that IM discontinuation at the time of stable complete molecular remission (CMR) may still result in hematologic relapse.8,,,–12 CML persistence supposedly results from an inherent insensitivity to IM of the CML stem and progenitor cells.13,–15 Various mechanisms may account for CML persistence under IM, including, for example, BCR-ABL overexpression,14,16,17 drug in- and efflux mechanisms,18,–20 and ABL kinase point mutations.21 Alternatively, the number of patients with undetectable BCR-ABL transcripts rises with longer IM treatment duration and approached 52% after 5 years in a subcohort of The International Randomized Study of Interferon and STI571.22 More intriguingly, in a trial with 60 patients in stable CMR, 41% showed an ongoing PCR negativity 18 months after IM discontinuation.10 These clinical results are clearly intriguing in view of the current model that CML precursors and HSCs are essentially IM-insensitive.13,–15 However, the latter hypothesis was derived mainly by short-term in vitro IM exposure experiments using IM-naive CD34+ samples and untreated patients with newly diagnosed CML (CML-Dx).13,–15 Biologic or genetic characteristics of persisting CD34+ CML cells are still largely undefined.

In an attempt to approach mechanisms of CML persistence during major molecular remission (MMR), we sought to track residual disease in different bone marrow fractions of patients in MMR to subsequently genetically analyze individual persisting clones. An intriguing observation resulting from this approach was that IM therapy diminishes CML disease load in all marrow compartments, including the primitive fraction, whereby persistence may result from a selective survival of CML precursors with only low BCR-ABL expression.

Methods

Patient samples and assessment of clinical response

Primary CML progenitor cells were isolated from bone marrow aspirates (30 mL) of patients with initial diagnosis of chronic phase of CML, CML-Dx patients (n = 12; supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), and, in a second cohort of patients during routine cytogenetic follow up biopsies in MMR (including CMR), MMR patients (n = 19; Table 1). Patients were treated within multicenter prospective CML studies and gave written informed consent to the donation in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Marburg. Patients' molecular response was assessed by determining the BCR-ABL to ABL mRNA transcript ratio isolated from the peripheral blood of the patients using quantitative RT-PCR and expressed according to the international scale as described previously.23,24

Selection of CD34+ progenitors

Bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNCs) were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density-gradient centrifugation (density, 1.077 ± 0.001 g/mL; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) for 20 minutes at 2744 rpm. CD34+ cells were enriched from BMMNCs by using CD34+ immunomagnetic column separation (MACS) as per the manufacturer's protocol (Miltenyi Biotech).

Cell sorting

MACS-enriched CD34+ cells from CML-Dx and MMR patients were stained with the following FITC-conjugated antibodies against lineage antigens (all from BD Biosciences) to gate for lin-negative (lin−) cells: CD2 (S5.2), CD3 (HIT3a), CD4 (RPA-T4), CD8 (HIT8a), CD14 (MΦP9), CD19 (ID-3), CD20 (2H7), CD56 (NCAM 16.2), and GPA (HIR2). In addition, cells were stained with PE-Cy7–conjugated anti-CD34 (8G12), PerCP-Cy5.5–conjugated anti-CD38 (HIT2), PE-conjugated anti-CD123 (9F5), and APC-conjugated anti–CD45-RA (HI100) antibodies (all from BD Biosciences) to define a lin−CD34+CD38− population (referred to as HSC) that enriches for HSCs and contained—after live gating—between 4% and 15% of lin−CD34+ cells. Myeloid progenitor subpopulations were sorted from the lin−CD34+CD38+ fraction with antibodies against CD45-RA and IL-3 receptor α (IL-3Rα) that separated 3 distinct populations: common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) as lin−CD34+CD38− IL-3Rαlow CD45RA−, candidate granulocyte macrophage progenitors (GMPs) as lin−CD34+CD38− IL-3RαlowCD45RA+), and megakaryocyte erythroid progenitors (MEPs) as lin−CD34+CD38− IL-3Rα−, CD45RA−. Cells were analyzed and sorted as described previously by MoFlo cytometer (Dako Colorado).25

mRNA isolation and qualitative RT-PCR for BCR-ABL

Messenger RNA (mRNA) was extracted and cDNA was synthesized essentially as described previously.25,26 In particular, mRNA was isolated from sorted bone marrow cells that had been pre-enriched before sorting for CD34+ cells using MACS methodology. Cells were directly sorted (Figure 1A) into RLT lysis buffer of the RNeasy micro kit (QIAGEN).

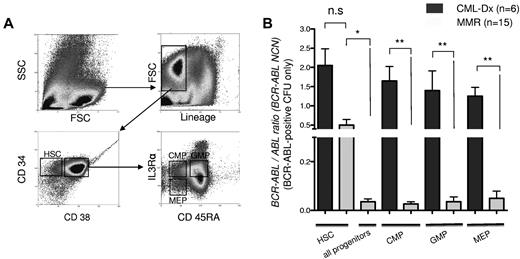

Detection of BCR-ABL mRNA transcripts in bone marrow subpopulations of CML-Dx and MMR patients. (A) Sorting strategy of MACS-enriched CD34+ cells. The lineage-negative subfraction was divided into lin−CD34+CD38− cells, enriching for HSCs, and a lin−CD34+CD38+ fraction that was further gated according to IL-3Rα and CD45RA staining into CMP, GMP, and MEP as indicated. (B) Quantitative real-time BCR-ABL PCR, normalized to ABL. Columns represent mean BCR-ABL NCN ± SEM of sorted subfractions (as indicated) from CML patients at diagnosis (CML-Dx) or during MMR (**P < .01; *P < .05 according to 1-way ANOVA; Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn multiple comparison posttesting).

Detection of BCR-ABL mRNA transcripts in bone marrow subpopulations of CML-Dx and MMR patients. (A) Sorting strategy of MACS-enriched CD34+ cells. The lineage-negative subfraction was divided into lin−CD34+CD38− cells, enriching for HSCs, and a lin−CD34+CD38+ fraction that was further gated according to IL-3Rα and CD45RA staining into CMP, GMP, and MEP as indicated. (B) Quantitative real-time BCR-ABL PCR, normalized to ABL. Columns represent mean BCR-ABL NCN ± SEM of sorted subfractions (as indicated) from CML patients at diagnosis (CML-Dx) or during MMR (**P < .01; *P < .05 according to 1-way ANOVA; Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn multiple comparison posttesting).

Alternatively, one individual CFU, containing ∼ 100 to 200 cells was picked from the CFU agar and transferred into RLT buffer. mRNA was transcribed into 20 μL of cDNA using SuperScript reverse transcriptase (QIAGEN) and random hexamer primers (MBI Fermentas).

Quantitative BCR-ABL PCR

Quantitative PCR analysis for BCR-ABL expression of bone marrow samples was performed using the IPSOGEN kit and protocol (Luminy Biotech Enterprises); this protocol quantifies BCR-ABL copy numbers relative to a total ABL copy number using a real-time TaqMan method and an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detector (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences).

We used 5 μL of cDNA as template in a 25-μL PCR reaction. Any BCR-ABL and ABL real-time PCR for individual CFUs was performed in duplicate, respectively. Cycling conditions were as recommended by the manufacturer: initial denaturation at 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 10 minutes, 50 cycles of amplification at 95°C for 15 seconds, and annealing at 60°C for 1 minute. Raw ct values obtained from the sample analysis were transformed in to an absolute copy number using a plasmid dilution standard curve delivered by the manufacturer: single plasmid standards for BCR-ABL (with 5 serial dilutions ranging from 101 to 106 copies/5 μL) and for ABL (with 4 serial dilutions ranging from 103 to 106 copies/5 μL). Each run included 2 no template controls and a high positive control (mRNA) provided by the kit. BCR-ABL results were reported as the ratio of BCR-ABL to ABL copy number, each representing averaged values of 2 technical replicates (duplicates) per sample and are expressed as the normalized copy number (NCN = bcr/ablCN/ablCN).

CFU assay

CFU assays were performed by plating 500 sorted cells from HSC, CMP, GMP, and MEP into a 35-mm culture dish (Cellstar) using 1 mL of complete methylcellulose agar (MethoCult medium H4435; Stem Cell Technologies) containing all necessary cytokines and reagents for CFU growth. After 14 to 18 days, individual CFUs were picked for mRNA isolation. For assessment of CFU growth of BCR-ABL– or mock-transduced murine progenitors, 1000 green fluorescent protein (GFP)–positive cells were seeded in triplicate Methocult agar in presence of IM at 3μM concentration or solvent (as control). Emerging colonies were counted after 14 days.

Interphase BCR-ABL FISH

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was performed on pooled colonies derived from colony-forming cells that were harvested from 1 methylcellulose agar plate. Cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in hypotonic (0.56%) KCl solution for 20 minutes at 37°C. Cells were then fixed with methanol/acetic acid (3:1) for 1 hour at room temperature. Hybridization using the Vysis LSI BCR/ABL dual-color, dual-fusion probes was performed according to manufacturer's instructions (Abbott Molecular; Abbott). One hundred cells were scored for the presence of a BCR-ABL translocation. Based on laboratory validation studies, a percentage of 5% or less of cells with a BCR-ABL fusion signal was considered as background. Florescent signals were evaluated using an epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss) and a Zeiss Plan-Neofluor 100d×/1.30 oil objective connected to a charge coupled device (CCD) camera controlled by the ISIS image analysis system (MetaSystems).

Retroviral transduction and cell culture

BMMCs were harvested by flushing femur and tibia from 6- to 8-week-old C57Bl/6 mice with a 26-gauge needle. Cells [32Dcl (32D)] were obtained from DSMZ cell culture collection (DSMZ) and maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with IL-3 (supplied as 10% WEHI-conditioned media), 10% FCS (PAA Laboratories), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Biochrom). Infectious viral particles were produced by transient transfection of phoenix eco packaging cells (kind gift of G. Nolan, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA) with the retroviral plasmid Mig210 (kind gift from Dr W. Pear, The University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) encoding the BCR-ABLp210 cDNA and GFP followed by harvesting of virus-containing supernatant after 2 days.

For retroviral transduction, BMMCs but not 32D cells were prestimulated for 48 hours in X-Vivo medium (Lonza Verviers) supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 200 μM l-glutamine (all PAA Laboratories), 6 ng/mL recombinant murine IL-3, 10 ng/mL recombinant murine IL-6, and 50 ng/mL recombinant murine stem cell factor (SCF, all ImmunoTools). Viral transduction of BMMCs and 32D cells was carried out by spinoculation (2500 rpm) for 90 minutes at 32°C in presence of 4 μg/mL polybrene, followed by incubation in presence of the same medium and growth factors. GFP+, that is, BCR-ABL–high expressing and –low expressing populations of BMMC and 32D cells (32D-BAhigh and 32D-BAlow), were sorted for further experimental use. Stable 32D-BA cells were maintained as 32D cells but without supplementation of IL-3.

ENU mutagenesis and cell-based IM resistance screen

The N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)–based mutagenesis screen was performed essentially as described previously.27 ENU was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; both from Sigma-Aldrich) at 50 mg/mL and stored in aliquots at −20°C. IM was kindly provided by Novartis Pharma. ENU was added to 32D-BAhigh and 32D-BAlow cells (5 × 106 cells/mL) at a concentration of 50 μg/mL followed by culturing for 24 hours. After washing 3 times with medium, cells were allowed to expand more than 1 week. 32D-BAlow and 32D-BAhigh cells were transferred into 96-well plates at 1 × 105 cells/well in a culture volume of 200 μL and supplemented with 2μM IM. Cultures were maintained for 4 weeks, replacing half of the medium every 48 hours and IM to yield a final concentration of 2μM. Wells were observed for cell growth by visual inspection under an inverted microscope, and media color change every 2 to 3 days for at least 4 weeks.27

Western blotting

Protein lysates and transfer were performed as described previously.25,28 The following primary antibodies were used for probing membranes: anti-cAbl mouse monoclonal antibody, clone 24-11 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-actin mouse mAb, clone AC-15 (Sigma-Aldrich). The secondary antibody was a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti–mouse antibody (Dako Deutschland). Proteins were visualized using the ECL Western blotting detection kit (GE Healthcare) and BioMax-MR film (Eastman Kodak).

Results

CML persistence in primitive and proliferating precursor compartments during MMR

Stem cell quiescence and BCR-ABL overexpression may contribute to IM insensitivity of CML.13,14,29 As a consequence, persistence is generally expected to occur preferably in the quiescent HSC fraction, and to a lesser extent in the proliferative progenitor compartments.29 To map disease persistence under IM therapy in hematopoiesis, bone marrow samples of patients with primary diagnosis of CML (CML-Dx patients, n = 6) and at the time of MMR (n = 15) were sorted into the HSC- and precursor-containing fractions (CMP, GMP, and MEP; Figure 1A) and analyzed for BCR-ABL expression using a quantitative RT-PCR approach. This revealed that IM treatment led to a significant decline of the mean BCR-ABL copy numbers in the mature precursor (P < .001) but not the HSC compartments (Figure 1B). The BCR-ABL load in MMR HSC fractions was higher than in pooled MMR progenitor compartments (P < .05%); Figure 1B). Thus, IM treatment reduces BCR-ABL–positive disease in all bone marrow fractions but presumably less rapidly in the HSC fraction.

IM reduces the number of BCR-ABL–positive CFUs in primitive and mature precursor fractions

IM treatment led to reduced BCR-ABL transcript levels in various bone marrow compartments (Figure 1B). This may be because of a progressive elimination of Philadelphia chromosome positive (Ph+) precursors but alternatively also an inhibition of BCR-ABL transcript levels in Ph+ clones.

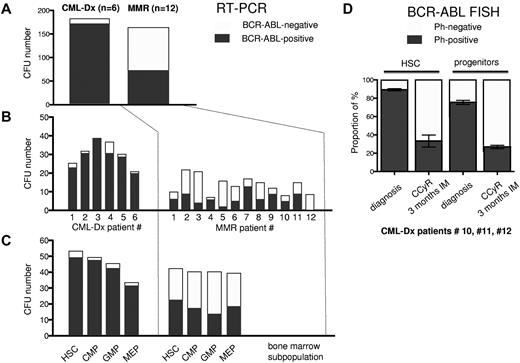

To elucidate this in more detail, we determined the proportion of BCR-ABL–negative and –positive CFUs in bone marrow subpopulations using BCR-ABL–specific RT-PCR. 251 single CFUs from 6 CML-Dx patients (supplemental Table 1) and 247 CFUs from 12 MMR patients (Table 1) were sorted from HSC, CMP, GMP, and MEP compartments and analyzed for BCR-ABL transcription. Only informative CFUs yielding sufficient mRNA were considered. Out of 184 informative CFU obtained from CML-Dx patients, 173 were BCR-ABL–positive (94%). In contrast, only 74 of 165 CFUs (44%) derived from 12 MMR patients were BCR-ABL mRNA-positive (Figure 2A). The proportion of BCR-ABL PCR-positive CFUs among the informative CFUs varied and may have been overestimated in some patients by a selection bias favoring the harvest of bigger and potentially more likely BCR-ABL–positive CFUs (Figure 2B). Nevertheless, compared with primary diagnosis CFUs, there were consistently less BCR-ABL–positive CFUs during MMR in committed (CMP, GMP, and MEP) and HSC fractions (Figure 2C).

MMR patients details

| Patient no. . | Sex, age, y . | Euro risk score . | Dose of imatinib/d, mg . | Y from diagnosis . | Y on imatinib . | Molecular response at the time of sorting (BCR-ABLIS), % . | Most recent molecular response (BCR-ABLIS), % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F, 59 | Low | 400 | 1* | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 831 | 2.3† | 2.3 | |||||

| 2 | F, 39 | Low | 800-400 | 2† | 2 | 0.033 | 0.017 |

| 614 | 3* | 3 | 0.0097 | ||||

| 4† | 4 | 0.019 | |||||

| 3 | M, 73 | Interm | 400 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 911 | 4*† | 4 | |||||

| 4 | M, 57 | Interm | 400 + IFN | 4* | 4 | 0.019 | 0.0076 |

| 1313 | |||||||

| 5 | M, 57 | Interm | 400 | 2.4*† | 2.4 | 0.025 | 0.011 |

| 1118.3 | |||||||

| 6 | M, 71 | Interm | 800-400 | 0.10* | 0.10 | 0 | 0 |

| 870.5 | 1.10† | 1.10 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 7 | M, 31 | Interm | 400 | 1* | 1 | 0.26 | 0.068 |

| 1098.1 | |||||||

| 8 | F, 59 | Unknown | 400 | 2.1* | 2.1 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | M, 58 | Interm | 800 | 2.7* | 2.7 | 0.0025 | 0.023 |

| 1438 | |||||||

| 10 | F, 41 | Low | 400 | 1.9† | 1.9 | 0.014 | |

| 445.3 | 3* | 3 | 0.064 | 0.031 | |||

| 4† | 4 | 0.031 | |||||

| 11 | F, 80 | 1083 | 400 | 1* | 1 | CCyR | |

| Interm | |||||||

| 12 | M, 53 | Interm | 400 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.24 | 0.034 |

| 1432 | 2.7*† | 2.7 | 0.041 | ||||

| 3.8† | 3.8 | 0.034 | |||||

| 13 | M, 38 | Low | 400 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 0.047 | 0.041 |

| 369.1 | |||||||

| 14 | M, 56 | Unknown | 400 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | M, 27 | Low | 400 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 0 | 0 |

| 245.2 | |||||||

| 16 | F, 40 | Low | 800-400 | 1† | 1 | 0.012 | 0.0085 |

| 699.5 | 2.10† | 2.10 | 0.0085 | ||||

| 17 | F, 64 | Interm | 800-400 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.025 | 0.0097 |

| 994.4 | |||||||

| 18 | F, 73 | Interm | 400 | 4.5† | 4.3 | 0.049 | 0.019 |

| 1443.7 | |||||||

| 19 | M, 67 | Low | 800 | 4.5† | 4.5 | 0.012 | 0.027 |

| 749 |

| Patient no. . | Sex, age, y . | Euro risk score . | Dose of imatinib/d, mg . | Y from diagnosis . | Y on imatinib . | Molecular response at the time of sorting (BCR-ABLIS), % . | Most recent molecular response (BCR-ABLIS), % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F, 59 | Low | 400 | 1* | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 831 | 2.3† | 2.3 | |||||

| 2 | F, 39 | Low | 800-400 | 2† | 2 | 0.033 | 0.017 |

| 614 | 3* | 3 | 0.0097 | ||||

| 4† | 4 | 0.019 | |||||

| 3 | M, 73 | Interm | 400 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 911 | 4*† | 4 | |||||

| 4 | M, 57 | Interm | 400 + IFN | 4* | 4 | 0.019 | 0.0076 |

| 1313 | |||||||

| 5 | M, 57 | Interm | 400 | 2.4*† | 2.4 | 0.025 | 0.011 |

| 1118.3 | |||||||

| 6 | M, 71 | Interm | 800-400 | 0.10* | 0.10 | 0 | 0 |

| 870.5 | 1.10† | 1.10 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 7 | M, 31 | Interm | 400 | 1* | 1 | 0.26 | 0.068 |

| 1098.1 | |||||||

| 8 | F, 59 | Unknown | 400 | 2.1* | 2.1 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | M, 58 | Interm | 800 | 2.7* | 2.7 | 0.0025 | 0.023 |

| 1438 | |||||||

| 10 | F, 41 | Low | 400 | 1.9† | 1.9 | 0.014 | |

| 445.3 | 3* | 3 | 0.064 | 0.031 | |||

| 4† | 4 | 0.031 | |||||

| 11 | F, 80 | 1083 | 400 | 1* | 1 | CCyR | |

| Interm | |||||||

| 12 | M, 53 | Interm | 400 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.24 | 0.034 |

| 1432 | 2.7*† | 2.7 | 0.041 | ||||

| 3.8† | 3.8 | 0.034 | |||||

| 13 | M, 38 | Low | 400 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 0.047 | 0.041 |

| 369.1 | |||||||

| 14 | M, 56 | Unknown | 400 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | M, 27 | Low | 400 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 0 | 0 |

| 245.2 | |||||||

| 16 | F, 40 | Low | 800-400 | 1† | 1 | 0.012 | 0.0085 |

| 699.5 | 2.10† | 2.10 | 0.0085 | ||||

| 17 | F, 64 | Interm | 800-400 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.025 | 0.0097 |

| 994.4 | |||||||

| 18 | F, 73 | Interm | 400 | 4.5† | 4.3 | 0.049 | 0.019 |

| 1443.7 | |||||||

| 19 | M, 67 | Low | 800 | 4.5† | 4.5 | 0.012 | 0.027 |

| 749 |

F indicates female; M, male; y, years; IS, international scale; and intern, intermediate.

Analysis of BCR-ABL expression in individual CFUs.

Analysis of BCR-ABL expression in total sorted bone marrow subfractions.

Frequency of BCR-ABL–negative and BCR-ABL–positive CFUs at diagnosis and during MMR. BCR-ABL–specific real-time PCR from individual CFUs was performed to identify the frequency of BCR-ABL–positive versus normal (BCR-ABL–negative) CFUs at the time of CML-Dx and MMR. (A) The sum of BCR-ABL–positive and normal CFUs is illustrated by dark versus gray bars, respectively. (B) The amount of BCR-ABL–positive and normal CFUs is shown for each patient individually. (C) The number of BCR-ABL–positive and normal CFUs is depicted depending on the indicated bone marrow compartment.

Frequency of BCR-ABL–negative and BCR-ABL–positive CFUs at diagnosis and during MMR. BCR-ABL–specific real-time PCR from individual CFUs was performed to identify the frequency of BCR-ABL–positive versus normal (BCR-ABL–negative) CFUs at the time of CML-Dx and MMR. (A) The sum of BCR-ABL–positive and normal CFUs is illustrated by dark versus gray bars, respectively. (B) The amount of BCR-ABL–positive and normal CFUs is shown for each patient individually. (C) The number of BCR-ABL–positive and normal CFUs is depicted depending on the indicated bone marrow compartment.

To rule out that the decline in the proportion of BCR-ABL–positive CFUs (Figure 2A-C) was the consequence of a repression of BCR-ABL transcription, we assessed the content of Ph+ CFUs using BCR-ABL–specific FISH in CML-Dx patients (10, 11, and 12) at diagnosis and 3 months after commencing IM. This confirmed that IM reduces the proportion of Ph+ CFUs in HSC and progenitor compartments. This became evident as early as 3 months after initiation of IM treatment (Figure 2D; Table 2). At this point, patients 10 and 11 had achieved a CCyR and almost an MMR. Patient 12 achieved a CCyR 3 months later.

Longitudinal analysis of imatinib response in bone marrow subfractions

| CML-Dx patient . | Diagnosis . | Remission after 3 mo of IM treatment . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. . | Sex, age, y . | BCR-ABL+ FISH from pooled CFUs, % . | BCR-ABLIS in PB,% . | BCR-ABL + FISH from pooled CFUs, % . | ||||||

| HSC . | CMP . | GMP . | MEP . | . | HSC . | CMP . | GMP . | MEP . | ||

| 10* | F, 39 | 90 | 86 | 81 | 70 | CCyR (0.47) | 30 | 20 | 30 | 25 |

| 11* | M, 48 | 87 | 68 | 72 | 76 | CCyR (0.27) | 46 | 29 | 32 | 30 |

| 12* | M, 48 | 91 | 85 | 72 | 70 | 1/12 Ph+ (n.a.) | 24 | 32 | 28 | 16 |

| CML-Dx patient . | Diagnosis . | Remission after 3 mo of IM treatment . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. . | Sex, age, y . | BCR-ABL+ FISH from pooled CFUs, % . | BCR-ABLIS in PB,% . | BCR-ABL + FISH from pooled CFUs, % . | ||||||

| HSC . | CMP . | GMP . | MEP . | . | HSC . | CMP . | GMP . | MEP . | ||

| 10* | F, 39 | 90 | 86 | 81 | 70 | CCyR (0.47) | 30 | 20 | 30 | 25 |

| 11* | M, 48 | 87 | 68 | 72 | 76 | CCyR (0.27) | 46 | 29 | 32 | 30 |

| 12* | M, 48 | 91 | 85 | 72 | 70 | 1/12 Ph+ (n.a.) | 24 | 32 | 28 | 16 |

IS indicates international scale; PB, peripheral blood; F, female; M, male; n.a., not available; and HSC, lin−CD34+CD38− cells, enriched for stem cells.

CML-Dx patients (see supplemental Table 1) were treated for 3 months with IM.

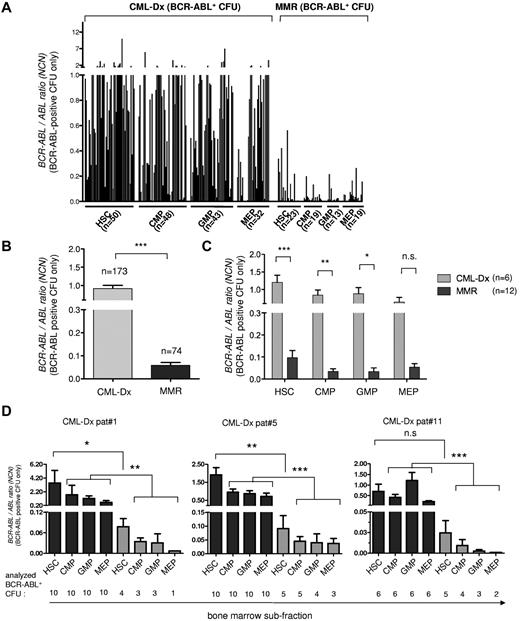

IM treatment selects for the persistence of CML CFUs with low BCR-ABL expression

Lower BCR-ABL expression in total marrow subfractions during MMR (Figure 1B) also would be compatible with reduced BCR-ABL copy number expression in individual persisting CML CFUs. Therefore, we next quantitatively evaluated BCR-ABL transcript levels of the BCR-ABL PCR-positive CFUs identified above (Figure 2A-C). This revealed at first a substantial variability in the repertoire of BCR-ABL expression strength of CML-Dx CFUs (Figure 3A). More intriguingly, BCR-ABL–positive CML-Dx CFU expressed on average significantly more BCR-ABL copies than BCR-ABL–positive CFUs from MMR patients (Figure 3B). This was true irrespective of whether comparing CML-Dx and MMR CFUs from the primitive or committed progenitor compartments (Figure 3C). BCR-ABL expression levels also were longitudinally analyzed in CFUs isolated from different bone marrow compartments of the same CML-Dx patients (1, 5, and 11) before and after IM treatment (Figure 3D; supplemental Table 1). This confirmed that the mean BCR-ABL transcript levels of remission CFU decline under IM therapy. They were significantly lower as early as 3 months after commencing IM (Figure 3D; Table 2).

BCR-ABL expression analysis of individual BCR-ABL–positive CFU using PCR. The BCR-ABL expression levels of BCR-ABL–positive CFU from CML-Dx and during MMR are shown, reported as the normalized copy number ratio of BCR-ABL. (A) Each column represents the BCR-ABL expression value of an individual CFU harvested from the indicated subfraction. (B) BCR-ABL expression of all analyzed BCR-ABL–positive CFUs from CML-Dx (gray) versus MMR (dark). Bars represent means ± SEM (***P < .0001, according to Mann-Whitney t test. (C) Comparison of the BCR-ABL expression level of BCR-ABL–positive CFUs from CML-Dx (gray) versus MMR (dark) sorted from bone marrow compartments as indicated. Bars represent mean values ± SEM (***P < .0001; **P < .01; *P < .05). Statistical significance was assessed using a 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. (D) BCR-ABL mRNA expression in individual BCR-ABL–positive CFUs (means ± SEM) at initial diagnosis (black) and 3 months after initiation of IM treatment (gray) in individual patients (***P < .0001; **P < .001; *P < .05). Statistical significance was assessed using Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn multiple comparison test to adjust for multiple comparisons.

BCR-ABL expression analysis of individual BCR-ABL–positive CFU using PCR. The BCR-ABL expression levels of BCR-ABL–positive CFU from CML-Dx and during MMR are shown, reported as the normalized copy number ratio of BCR-ABL. (A) Each column represents the BCR-ABL expression value of an individual CFU harvested from the indicated subfraction. (B) BCR-ABL expression of all analyzed BCR-ABL–positive CFUs from CML-Dx (gray) versus MMR (dark). Bars represent means ± SEM (***P < .0001, according to Mann-Whitney t test. (C) Comparison of the BCR-ABL expression level of BCR-ABL–positive CFUs from CML-Dx (gray) versus MMR (dark) sorted from bone marrow compartments as indicated. Bars represent mean values ± SEM (***P < .0001; **P < .01; *P < .05). Statistical significance was assessed using a 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. (D) BCR-ABL mRNA expression in individual BCR-ABL–positive CFUs (means ± SEM) at initial diagnosis (black) and 3 months after initiation of IM treatment (gray) in individual patients (***P < .0001; **P < .001; *P < .05). Statistical significance was assessed using Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn multiple comparison test to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Low BCR-ABL expression restricts IM-sensitivity of primary progenitors in vitro

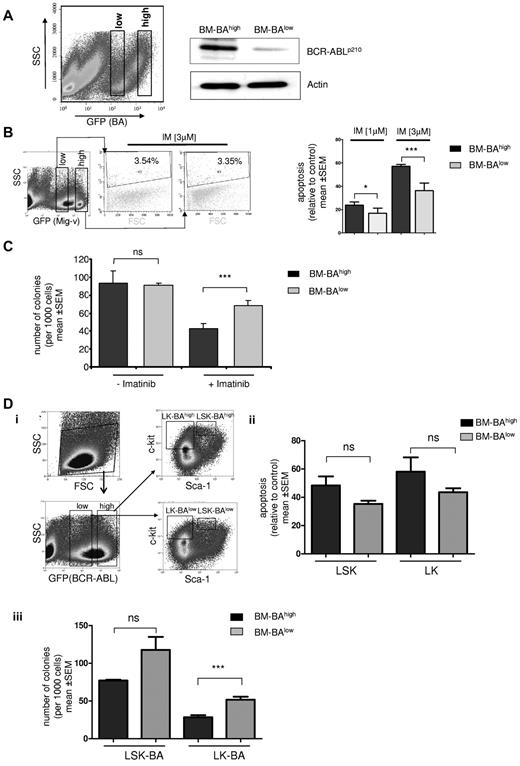

Based on the findings in the previous paragraph, it was tempting to speculate that IM therapy preferably targets clones with higher BCR-ABL expression, resulting in the persistence of IM-insensitive disease with lower BCR-ABL expression. In an attempt to experimentally address this issue in vitro, primary mouse bone marrow cells were transduced with a GFP-expressing BCR-ABL construct. The GFP-positive fraction was sorted into a GFP-high expressing and a GFP-low expressing population to select for low and high levels of BCR-ABL (Figure 4A). The GFP staining intensity correlated with the BCR-ABL protein levels as confirmed by Western blotting (Figure 4A). Sorted BCR-ABL–overexpressing bone marrow cells (BM-BAhigh) and BCR-ABL–low expressing bone marrow cells (BM-BAlow) or GFP-high/low vector-transduced controls were treated with IM at a concentration of 1 or 3μM for 48 hours in presence of serum and growth factors. Intriguingly, whereas IM at 3μM had no effect on apoptosis in empty vector transduced marrow, BM-BAlow underwent significantly less apoptosis than BM-BAhigh with either 1 or 3μM of IM (Figure 4B). In addition, IM inhibited colony formation significantly more potently in BM-BAhigh than in BM-BAlow cells (P = .006; Figure 4C). There was no significant difference in the number of colonies in BM-BAhigh and BM-BAlow in the absence of IM (Figure 4C). Because CFU formation is a measure for proliferative potential of precursor cells in vitro, these results suggested that low BCR-ABL expression level restrict IM sensitivity.

Effect of BCR-ABL expression level on IM sensitivity in primary bone marrow cells. (A) BCR-ABL GFP-transduced murine BMMCs were analyzed by FACS for GFP staining intensity and sorted into GFP-high (BM-BAhigh) and GFP-low (BM-BAlow) fractions using gates as indicated (left); transduced cells were cultured for 72 hours after sorting, and total protein was extracted. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-ABL antibodies. The membrane was reprobed using an anti-actin antibody as a loading control (right). (B) Left: empty vector GFP (Mig-v)–expressing BMMCs were sorted according to the indicated gates into high and low GFP-expressing populations and separately treated with 3μM IM for 48 hours. Apoptosis was assessed using propidium iodide staining as indicated. A representative flow cytometry plot of 2 independent experiments is shown. SSC indicates side scatter; FSC, forward scatter. Right: propidium iodide staining to measure IM-induced apoptosis by flow cytometry in BM-BAhigh– and BM-BAlow–expressing BMMCs. Apoptosis is displayed relative to untreated controls after treatment for 48 hours with IM at 1 or 3μM. Columns and error bars represent means ± SEM (*P < .05; ***P < .0001). (C) We sorted and seeded 1000 BM-BAhigh and 1000 BM-BAlow cells, respectively, in 1 mL of semisolid methylcellulose medium with and without 3μM imatinib, and after 14 days colonies were counted. The data were obtained from 3 independent experiments; columns represent means ± SEM (***P < .001 according to Mann–Whitney t test). (D) Sorting strategy of bone marrow cells transduced with BCR-ABL GFP to BAhigh/lowlin−sca1+c-kit+ (LSK) and lin−c-kit+ (LK) populations (i). Apoptosis assessment in BAhigh/low LK and LSK after treatment with IM at 3μM for 48 hours using propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry (ii). CFU assay as in panel C (iii) using sorted BAhigh/low LK and LSK (***P = .008 according to Mann-Whitney t test; n.s., P > .05).

Effect of BCR-ABL expression level on IM sensitivity in primary bone marrow cells. (A) BCR-ABL GFP-transduced murine BMMCs were analyzed by FACS for GFP staining intensity and sorted into GFP-high (BM-BAhigh) and GFP-low (BM-BAlow) fractions using gates as indicated (left); transduced cells were cultured for 72 hours after sorting, and total protein was extracted. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-ABL antibodies. The membrane was reprobed using an anti-actin antibody as a loading control (right). (B) Left: empty vector GFP (Mig-v)–expressing BMMCs were sorted according to the indicated gates into high and low GFP-expressing populations and separately treated with 3μM IM for 48 hours. Apoptosis was assessed using propidium iodide staining as indicated. A representative flow cytometry plot of 2 independent experiments is shown. SSC indicates side scatter; FSC, forward scatter. Right: propidium iodide staining to measure IM-induced apoptosis by flow cytometry in BM-BAhigh– and BM-BAlow–expressing BMMCs. Apoptosis is displayed relative to untreated controls after treatment for 48 hours with IM at 1 or 3μM. Columns and error bars represent means ± SEM (*P < .05; ***P < .0001). (C) We sorted and seeded 1000 BM-BAhigh and 1000 BM-BAlow cells, respectively, in 1 mL of semisolid methylcellulose medium with and without 3μM imatinib, and after 14 days colonies were counted. The data were obtained from 3 independent experiments; columns represent means ± SEM (***P < .001 according to Mann–Whitney t test). (D) Sorting strategy of bone marrow cells transduced with BCR-ABL GFP to BAhigh/lowlin−sca1+c-kit+ (LSK) and lin−c-kit+ (LK) populations (i). Apoptosis assessment in BAhigh/low LK and LSK after treatment with IM at 3μM for 48 hours using propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry (ii). CFU assay as in panel C (iii) using sorted BAhigh/low LK and LSK (***P = .008 according to Mann-Whitney t test; n.s., P > .05).

The impact of BCR-ABL expression on CFU formation inhibition and apoptosis induction by IM also was investigated in sorted populations of lin−sca1+c-kit+ (LSK; enriching HSCs) and lin−c-kit+ (LK; progenitors) that had been separated into GFP (BA)high / low populations before IM treatment (Figure 4Di). BAhigh LSK and LK were more sensitive to undergo apoptosis compared with BAlow LSK and LK, but this difference did not reach statistical significance after 48 hours of treatment (Figure 4Dii). Colony formation was substantially more inhibited by IM in BAhigh-LK compared with BAlow-LK progenitors (P = .008; Figure 4Diii), and as a trend also in BAhigh compared with BAlow LSK (Figure 4Diii). Together, BCR-ABL expression levels determine IM sensitivity of primary hematopoietic cells. High BCR-ABL expression did not confer IM resistance but rather augmented the antiproliferative, and as a trend also the proapoptotic effects, of IM in vitro. Similar results have been reported previously by Modi et al using BCR-ABLhigh/low–transduced human CD34+ cells.

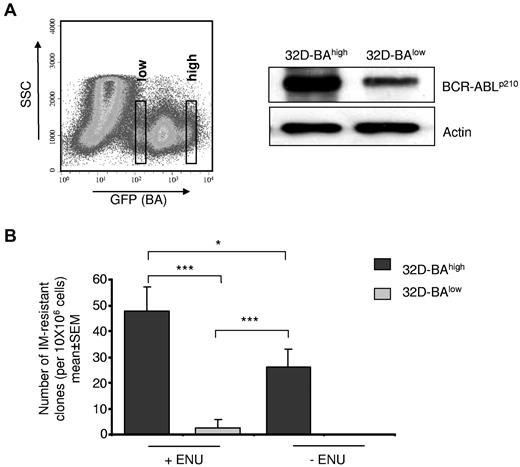

BCR-ABL expression level regulates kinase mutation development

BCR-ABL kinase mutations cause IM resistance30,31 and supposedly mediate persistence under IM.21 We asked to which extent BCR-ABL expression may impact BCR-ABL kinase mutation generation. A cell-based BCR-ABL kinase mutagenesis screen was used that produces BCR-ABL kinase point mutations as the main resistance mechanism.27 The murine myeloid 32D cell line was transduced with a BCR-ABL plasmid also encoding for GFP. Resulting 32D-BA cells were sorted according to their GFP staining intensity into putative 32D-BAhigh– and 32D-BAlow–expressing cell populations (Figure 5A). Western blot analysis confirmed that BCR-ABL expression level correlated with the GFP staining intensity (Figure 5A). Cells (32D-BAlow and 32D-BAhigh) were exposed, respectively, to IM at 2μM, and wells showing outgrowth of viable cells after 21 to 28 days were counted as IM-resistant clones.

Effect of BCR-ABL expression and chemical mutagenesis by ENU on kinase point mutation rates. (A) BA-transduced 32D cells were sorted by flow cytometry on the basis of GFP staining intensity into 32D-BAlow and 32D-BAhigh cells (right). BCR-ABL protein expression was confirmed 72 hours after sorting by Western blotting using anti-Abl antibodies. The blot was reprobed with anti-actin antibodies as a loading control (left). (B) Cell-based BCR-ABL kinase mutation assay. 32D-BAlow and 32D-BAhigh cells were exposed to ENU and 1 week later were exposed for 4 weeks to 2μM IM. The number of outgrowing resistant clones is given relative to the total input cell number per 96-well plate. Data represent means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments (***P < .001; *P < .05 according to 2-way ANOVA, with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons).

Effect of BCR-ABL expression and chemical mutagenesis by ENU on kinase point mutation rates. (A) BA-transduced 32D cells were sorted by flow cytometry on the basis of GFP staining intensity into 32D-BAlow and 32D-BAhigh cells (right). BCR-ABL protein expression was confirmed 72 hours after sorting by Western blotting using anti-Abl antibodies. The blot was reprobed with anti-actin antibodies as a loading control (left). (B) Cell-based BCR-ABL kinase mutation assay. 32D-BAlow and 32D-BAhigh cells were exposed to ENU and 1 week later were exposed for 4 weeks to 2μM IM. The number of outgrowing resistant clones is given relative to the total input cell number per 96-well plate. Data represent means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments (***P < .001; *P < .05 according to 2-way ANOVA, with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons).

Cells (32D-BAhigh) generated significantly more resistant clones compared with 32D-BAlow cells. Intriguingly, the impact of chemical mutagenesis by ENU on the frequency of IM resistance development was significantly weaker than the effect of high BCR-ABL expression, because the number of emerging IM-resistant clones was a multiple fold lower in ENU-treated 32D-BAlow cells than in ENU-naive 32D-BAhigh cells (P = .006; Figure 5B). Hence, persistence of precursors with low BCR-ABL expression would explain the low propensity of kinase mutation development that is clinically observed during MMR.

Discussion

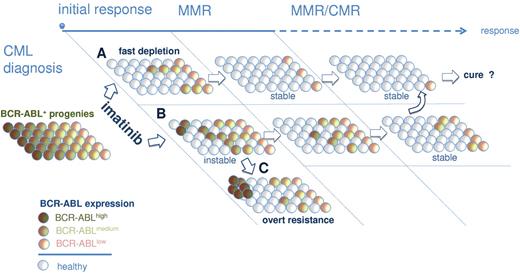

A large body of evidence previously suggested that BCR-ABL overexpression in primitive (lin−CD34+CD38−) and mature (CD34+CD38+) progenitors may contribute to the failure of IM to eradicate CML.14,16,17,32 Recently, Abe et al reported that residual CML disease accumulates in the lin−CD34+CD38− fraction.33 Here, we here showed that BCR-ABL remains detectable at a low level during MMR in primitive and committed bone marrow populations (Figure 1B). However, we also wanted to specifically assess BCR-ABL expression of dormant CML clones under IM therapy. Intriguingly, we found evidence to suggest that persisting primitive and mature BCR-ABL–positive clones (CFUs) isolated from CCyR and MMR patients consistently expressed less BCR-ABL copies than CFUs from primary diagnosis samples (Figure 3). Notably, a preferential survival of BCR-ABLlow–expressing CFU under IM therapy could not only be demonstrated after long-term IM therapy (eg, at the time of MMR) but also as early as 3 months after commencing IM therapy in CML-Dx patients 1, 5, and 11 (Figure 3D). It is therefore tempting to speculate that a rapid and stable eradication of BCR-ABL–overexpressing clones after start of IM treatment is an important requirement for the establishment of MMR, which has an excellent long-term prognosis4,6,34 If, in turn, IM fails to eliminate these supposedly “dangerous” BCR-ABLhigh expresser clones, the odds for evolution of secondary IM resistance emerging from these clones probably increases (Figure 6). Indeed, patients treated in progressed phases of CML overexpress BCR-ABL35,–37 and regularly encounter IM resistance.38,–40 There is also solid evidence for a direct link among BCR-ABL expression, genetic instability, and IM resistance.41,,–44 Using an immortalized BCR-ABL–dependent cell line model resembling blast crisis cells, we also provided such evidence by showing that BCR-ABL overexpression catalyzes mutagenesis and IM resistance development to an even greater extent than chemical mutagenesis by ENU (Figure 5B).

Model for IM-mediated shaping of the BCR-ABL expression repertoire in persisting precursor cells. Immature and mature progenitors express variable levels of BCR-ABL at primary diagnosis of CML (left). BAhigh clones are more sensitive to IM, leading to their preferential depletion from bone marrow compartments in optimal responders (A). A delayed depletion of genetically less stable BAhigh precursors (B) increases the risk for emergence of secondary mutations and IM resistance (C). Depletion of BAhigh and persistence of primarily BAlow progenies would conceivably be required for stable long-term remissions under IM.

Model for IM-mediated shaping of the BCR-ABL expression repertoire in persisting precursor cells. Immature and mature progenitors express variable levels of BCR-ABL at primary diagnosis of CML (left). BAhigh clones are more sensitive to IM, leading to their preferential depletion from bone marrow compartments in optimal responders (A). A delayed depletion of genetically less stable BAhigh precursors (B) increases the risk for emergence of secondary mutations and IM resistance (C). Depletion of BAhigh and persistence of primarily BAlow progenies would conceivably be required for stable long-term remissions under IM.

The mechanisms by which low BCR-ABL expression limits IM sensitivity are not entirely clear but could be related to the induction of weaker oncogenic dependence. Previously, Modi et al made similar observations.45 They transduced normal primary human progenitor cells engineered to express low and high BCR-ABL levels and found a diminished IM sensitivity in the case of lower BCR-ABL expression.45 Importantly, their findings, and our findings, do not contradict previous evidence that BCR-ABL overexpression may cause IM resistance.46,47 However, it must be acknowledged that the cellular context of BCR-ABL expression might decisively control the biologic effects of the oncoprotein during transformation, progression, and drug resistance.

In summary, it is suggested here that IM treatment and achievement of MMR is associated with a uniform shaping of the BCR-ABL expression repertoire characterized by the preferential survival of dormant BCR-ABLlow–expressing clones that are less IM-sensitive and genetically more stable (Figure 6). Although therapeutic strategies targeting BCR-ABL–independent mechanisms of persistence may be rational,24,48,49 the herein proposed model supports the clinical observation that achieving MMR is safe to prevent progression.

A persistence model as illustrated in Figure 6 also would be compatible with the idea that IM therapy may be capable to eliminate CML and thus enable cure as implied from the Stop Imatinib data.10 However, the latter scenario would implicate that BCR-ABLlow dormant cells also maintain a level of BCR-ABL expression sufficient to generate a status of BCR-ABL oncogene dependence.

Presented in part in abstract form at the 51st annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, New Orleans, LA, December 5, 2009.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sonja Tajstra, Thorsten Volkmann, Kathleen Stabla, and Gavin Giel for excellent technical assistance in the isolation, preparation, and sorting of bone marrow samples. They thank Dr T. Lange for helping to assemble patient samples. They also especially thank Prof Dr Koch and Dr Fritz for providing technical and infrastructural assistance in performing BCR-ABL FISH.

This work was supported by Deutsche José Carreras Leukämie-Stiftung e.V. (DJCLS-R 09/04, A.B.; and H 01/03, A.H.); Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Klinische Forschergruppe KFO210 TP1 (A.B.) and TP3 (A.N.); Transregio SFB 17 (A.B. and A.N.); Behring Röntgen Foundation TP51-0057 (A.B.); a research grant from the University Medical Center Gießen and Marburg TP 24/2010 (A.B.); and the LOEWE-consortium “Tumor and Inflammation” (A.B.).

Authorship

Contribution: A.B. designed and coordinated the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; A.K. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, compiled the figures, and helped writing the manuscript; C.B. performed and supervised cell sorting and flow cytometry; and A.H. and A.N. coordinated the research, analyzed and discussed the data, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.B. and A.H. received research funding from Novartis Pharma. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Andreas Burchert, Philipps Universität Marburg, Universitätsklinikum Gießen und Marburg, Standort Marburg, Klinik für Hämatologie, Onkologie und Immunologie, 35043 Marburg, Germany; e-mail: burchert@staff.uni-marburg.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal