Abstract

To migrate efficiently through the interstitium, dendritic cells (DCs) constantly adapt their shape to the given structure of the extracellular matrix and follow the path of least resistance. It is known that this amoeboid migration of DCs requires Cdc42, yet the upstream regulators critical for localization and activation of Cdc42 remain to be determined. Mutations of DOCK8, a member of the atypical guanine nucleotide exchange factor family, causes combined immunodeficiency in humans. In the present study, we show that DOCK8 is a Cdc42-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor that is critical for interstitial DC migration. By generating the knockout mice, we found that in the absence of DOCK8, DCs failed to accumulate in the lymph node parenchyma for T-cell priming. Although DOCK8-deficient DCs migrated normally on 2-dimensional surfaces, DOCK8 was required for DCs to crawl within 3-dimensional fibrillar networks and to transmigrate through the subcapsular sinus floor. This function of DOCK8 depended on the DHR-2 domain mediating Cdc42 activation. DOCK8 deficiency did not affect global Cdc42 activity. However, Cdc42 activation at the leading edge membrane was impaired in DOCK8-deficient DCs, resulting in a severe defect in amoeboid polarization and migration. Therefore, DOCK8 regulates interstitial DC migration by controlling Cdc42 activity spatially.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are specialized APCs that play a critical role in the initiation of adaptive immune responses.1 After antigen exposure, DCs phagocytose antigens in peripheral tissues and migrate via the afferent lymphatic vessels into the draining lymph nodes (LNs) to stimulate T cells.2,3 During this process, DCs switch their sessile sampling behavior to a highly migratory one, which is characterized by the acquisition of a polarized morphology and increased expression of the chemokine receptor CCR7. Whereas CCR7 signals guide DCs to the LN parenchyma,4 DCs must pass through a 3-dimensional (3D) interstitial space composed of fibrillar extracellular matrix (ECM) before reaching their destination. To perform this task efficiently, DCs constantly adapt their shape to the given structure of the interstitial ECM and follow the path of least resistance.5 This amoeboid migration of DCs occurs independently of adhesion to specific substrates and ECM degradation,6,7 yet its regulatory mechanisms are poorly understood.

Cdc42 is a member of the Rho family of small GTPases that function as molecular “switches” by cycling between GDP-bound inactive states and GTP-bound active states.8 Cdc42 exists in the cytosol in the GDP-bound form and is recruited to membranes, where its GDP is exchanged for GTP because of the action of one or more guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs). Once activated, Cdc42 binds to multiple effector molecules and regulates various cellular functions. Cdc42 is known to act as a master regulator of cell polarity in eukaryotic organisms ranging from yeasts to humans.8 In addition, a recent study revealed that Cdc42-deficient DCs are unable to migrate in 3D environments, whereas they exhibit only limited defects in a 2-dimensional (2D) setting.9 This phenotype is totally different from that caused by Rac1 and Rac2 deficiency, which abolishes DC motility itself.10 Therefore, to elucidate the mechanism controlling interstitial DC migration, the identification of upstream regulators and downstream effectors of Cdc42 activity is important. Thus far, deletion of downstream effectors such as Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein, Eps8, or fascin has been shown to affect DC migration in vitro and in vivo.11-14 However, little is known about upstream regulators critical for the localization and activation of Cdc42 during DC migration.

DOCK8 is a member of the evolutionarily conserved DOCK family proteins that function as GEFs for the Rho family of GTPases.15,16 Recently, the signaling and functions of DOCK8 have gained attention because of the discovery of a combined immunodeficiency syndrome caused by Dock8 mutations in humans.17,18 Patients with homozygous inactivating Dock8 mutations exhibit recurrent sinopulmonary infections typical of humoral immunodeficiency and severe viral infections suggestive of T-cell dysfunction. These patients also exhibit hyper IgE and are susceptible to atopic dermatitis.17,18 More recently, N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea–mediated mutagenesis in mice has revealed that DOCK8 plays an important role in B-cell immunologic synapse and long-lasting humoral immunity,19 and also contributes to survival of memory CD8+ T cells.20,21 DOCK8 contains the DHR-2 (also known as CZH2 or Docker) domain that is known to mediate the GTP-GDP exchange reaction.15,16,22,23 However, the substrate specificity of DOCK8 and its functions in DCs are currently unknown.

In the present study, we provide structural, functional, and biochemical evidence that DOCK8 is a Cdc42-specific GEF and critically regulates interstitial DC migration. By generating the knockout mice, we found that in the absence of DOCK8, DCs failed to accumulate in the LN parenchyma for T-cell priming. Although DOCK8 deficiency did not affect global Cdc42 activity, Cdc42 activation at the leading-edge membrane was impaired in DOCK8-deficient (Dock8−/−) DCs, resulting in a severe defect in amoeboid polarization and migration. Our results thus uncover a previously unknown function of DOCK8 and provide mechanistic insight into T-cell dysfunction associated with DOCK8 deficiency in humans.

Methods

Mice

Mice were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions in the animal facility of Kyushu University (Fukuoka, Japan). All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the committee of Ethics of Animal Experiments of Kyushu University.

Immunization, adoptive transfer, and T-cell response

Mice were immunized in the footpads with ovalbumin (OVA; 10 μg per mouse; Sigma-Aldrich) emulsified in complete Freund adjuvant (CFA). Seven days later, CD4+ T cells prepared from the popliteal LNs (1 × 105 cells) were cultured with T cell–depleted, irradiated C57BL/6 spleen cells (1 × 106 cells) in the presence of various concentrations of OVA protein for 72 hours, and 37 kBq of [3H]-thymidine was added during the final 16 hours of the culture. The OVA-specific T-cell response was also assayed by dilution of CFSE dye. For this purpose, CFSE-labeled OT-II transgenic CD4+ T cells (3.5 × 106 cells) were IV injected into mice 1 day before immunization, and flow cytometric analyses were carried out 72 hours after immunization. In some experiments, instead of immunization, OVA323-339 peptide-pulsed BM-derived DCs were given into the footpads 72 hours before the assays.

In vivo DC migration assays

After being labeled with PKH-26 and PKH-67 fluorescent cell linkers (Sigma-Aldrich), equal numbers of BM-derived Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs (1 × 106 cells) were injected subcutaneously into the hind footpads of C57BL/6 mice. Cells were prepared from the spleen and the popliteal and mesenteric LNs 48 hours after injection for flow cytometric analyses. In some experiments, migration of epidermal DCs was induced by applying 200 μL of 1% FITC isomer I (Sigma-Aldrich) in carrier solution (1:1 vol/vol acetone:dibutylphthalate) onto the shaved abdomen, and the frequency of FITC+ MHC II+ DCs was analyzed 24 and 48 hours later.

Ex vivo DC migration assays

The ears of C57BL/6 mice were mechanically split into dorsal and ventral halves, labeled with anti–LYVE-1 Ab, and immobilized with the epidermal side down. The dermis was overlaid with fluorescently labeled BM-derived DCs for 15 minutes at 37°C. After gently washing away noninfiltrated DCs, the ear sheets were imaged in a heated chamber every 2.5 minutes using an M205 FA stereomicroscope (Leica Microsystems). Velocities were calculated by analyzing with the manual tracking feature in MetaMorph Version 7.7.1.0 software (Molecular Devices). For immunofluorescence staining, ear sheets of C57BL/6 or CD45.1 congenic C57BL/6 mice were fixed with methanol for 5 minutes and stained for LYVE-1 with or without anti-CD45.2 Ab. Images were taken with a laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM 510 META; Carl Zeiss).

In vitro DC migration assays

EZ-Taxiscan chemotaxis assays were performed as described previously.24 3D collagen gel chemotaxis assays were performed with μ-Slide Chemotaxis3D (ibidi). For this purpose, cells were mixed with 1.65 mg/mL of collagen type I (BD Biosciences) in RPMI supplemented with 4% FCS and cast in the chamber before assays. After polymerization of the lattice, images were taken in a heated chamber every 2 minutes using an IX-81 inverted microscope (Olympus) equipped with a cooled CCD camera (CoolSNAP HQ; Roper Scientific), an IX2-ZDC laser-based autofocusing system (Olympus), and an MD-XY60100T-Meta automatically programmable XY stage (Sigma KOKI). Images were imported as stacks to ImageJ Version 1.41o software and analyzed with the manual tracking and the chemotaxis and migration tools. Migration of BW5147α−β− transfectants in 3D collagen gels was analyzed by placing collagen-cell mixtures on 35-mm glass-bottomed microwell dishes (MatTek). Images were taken and velocities were calculated with the manual tracking feature in MetaMorph software.

Intravital 2-photon microscopy of popliteal LNs

BM-derived DCs from Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− littermates were labeled with 5-(and-6)-(((4-chloromethyl)benzoyl)amino)tetramethylrhodamine (5μM; Invitrogen) and 7-amino-4-chloromethylcoumarin (20-200μM; Invitrogen), respectively, and vice versa. Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs were mixed at the ratio of 1:3-1:5, and the cells (1.2-1.5 × 106 cells; 20 μL) were injected into the footpads of C57BL/6 mice. At specified times, mice were anesthetized and the cortex side of the popliteal LN was surgically exposed. In some experiments, 30 μL of anti–mouse LYVE-1 eFluor 488 Ab (100 μg/mL) or 5 μL of FITC-dextran (265 000 average molecular weight; 2 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) was injected into the footpads before intravital 2-photon microscopy to identify the subcapsular sinus (SCS). Two-photon imaging was performed and analyzed with Volocity software (Improvision) as described previously.25,26

Pull-down assays

Extracts of human embryonic kidney 293T cells expressing hemagglutinin (HA)–tagged DOCK8, DOCK8 lacking the DHR-2 domain (residues 1638-2062; DOCK8 ΔDHR-2), or DOCK2 were incubated with GST-Cdc42, GST-Rac1, GST-RhoA, or GST immobilized on glutathione beads (50% suspension) in binding buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, 150mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.5) supplemented with 10mM EDTA (buffer E) or with 10mM MgCl2 plus 30μM GTPγS (buffer M) at 4°C for 60 minutes. To assess activation of Cdc42, Rac1, or RhoA, aliquots of the cell extracts were incubated with the GST-fusion Rac/Cdc42-binding domain of PAK1 or RhoA-binding domain of Rhotekin (both from Millipore) at 4°C for 60 minutes.

In vitro GEF assays

GST-Cdc42 and GST-Rac (15μM) were loaded with GDP in the reaction buffer (20mM MES-NaOH, 150mM NaCl, 10mM MgCl2, 0.4 mg/mL of BSA, and 20μM GDP, pH 7.0) on ice for 30 minutes. Recombinant DOCK8 DHR-2 (residues 1633-2071) and DOCK2 DHR-2 (residues 1195-1621) were incubated in the same buffer for 30 minutes at room temperature. GDP-loaded Cdc42 or Rac (100 μL) was mixed with N-methylanthraniloyl (mant)–GTP (3.6μM; Jena Bioscience) and allowed to equilibrate at 30°C for 8 minutes. After equilibration, DOCK8 DHR-2 or DOCK2 DHR-2 (50 μL) was added to the mixtures, and the change of mant-GTP fluorescence (excitation 360 nm, emission 440 nm) was monitored at 30°C using an XS-N spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices).

X-ray structure determination

The genes encoding the DOCK8 DHR-2 lacking lobe A (residues 1787-2067) and Cdc42 (residues 1-188 with T17N mutation) fragments were cloned into the expression vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) and cosynthesized using the large-scale dialysis mode of the Escherichia coli cell-free reaction. The DOCK8 DHR-2·Cdc42 complex crystals were grown at 20°C using the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion method by mixing the protein solution with an equal volume of reservoir solution containing 200mM di-potassium hydrogen phosphate and 20% PEG3350. The data were collected at 100 K at a wavelength of 1.0 Å at beamline NW12A of the Photon Factory (Tsukuba, Japan). The diffraction data were processed with the HKL2000 program.27 The structure of the DOCK8 DHR-2·Cdc42 complex was determined by molecular replacement using the coordinate of the DOCK9 DHR-2·Cdc42 complex (PDB code 2WM9) as a search model. The program PHENIX was used to calculate the initial phases.28 The model was corrected iteratively using the program Coot,29 and was refined using PHENIX.28 The quality of the model was inspected by the program PROCHECK.30 Graphic figures were created using the program PyMOL. The structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.pdb.org) under accession code 3VHL.

FRET-based imaging

Fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET; excitation 440 nm/emission peak 527 nm) and cyan fluorescent protein (CFP; excitation 440 nm/emission peak 475 nm) images were obtained using the Olympus IX-81 inverted microscope. For emission ratio imaging, the following filter sets were used: 440AF21 and 480AF30 for CFP, 440AF21 and 535AF26 for yellow fluorescent protein (YFP; excitation and emission filters; Omega Optical). A 455DRLP dichroic mirror (Omega Optical) was used for CFP and YFP. Cells were illuminated at 440 nm excitation with a CoolLED. After recordings were made, ratio images of FRET/CFP were created with MetaMorph software and were used to represent the efficiency of the FRET.

Supplemental methods

For cell preparation, protein expression and purification, subcellular fractionation, immunofluorescence microscopy, and retroviral transfection, see supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Statistical analysis

Results

Generation of Dock8−/− mice

To better understand the physiologic functions of DOCK8, we generated knockout mice by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells (supplemental Figure 1A-B). Correctly targeted embryonic stem cell clones were microinjected into C57BL/6 blastocysts, and the male chimeras obtained were crossed with C57BL/6 female mice. Heterozygous mutant mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice for more than 9 generations, and Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− littermates were used in this study. The experiments with RT-PCR revealed that insertion of the Neo cassette results in an appearance of a stop codon at the N-terminal portion of DOCK8, leaving only 62 amino acid residues presumably intact. Consistent with this finding, DOCK8 expression was undetectable when spleen cell lysates from the knockout mice were analyzed by immunoblot (supplemental Figure 1C).

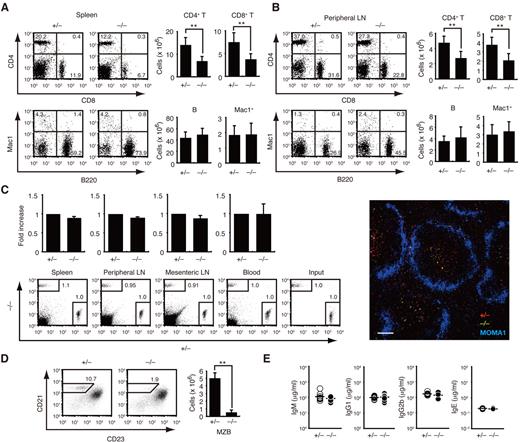

We first compared the number of leukocyte subsets and other immunologic parameters between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− littermates. Although T-cell development occurred normally in the absence of DOCK8 (supplemental Figure 2), the numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen and the peripheral LNs were reduced to 50%-60% of the Dock8+/− levels (Figure 1A-B), as reported in the N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea–induced mutant mice.19-21 This reduction did not result from the defect in T-cell homing, because Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− T cells migrated comparably into the T-cell zone of secondary lymphoid organs when IV injected into C57BL/6 mice (Figure 1C). Dock8−/− mice also exhibited a significant reduction of marginal zone B (MZB) cells (Figure 1D). Conversely, DOCK8 deficiency did not affect the number of mature B cells in secondary lymphoid organs or serum Ig levels under steady-state conditions (Figure 1A-B and E).

Effect of DOCK8 deficiency on leukocyte subsets under the steady state. (A-B) Splenocytes (A; n = 10 mice per group) and peripheral LN cells (B; n = 8 mice per group) from 6- to 7-week-old mice were analyzed for the expression of CD4 and CD8 or Mac1 and B220. The numerals in quadrants indicate the percentage of cells in each. The number of each subset of cells was compared between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− mice. **P < .01. (C) Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− T cells were labeled with different fluorescent dyes and IV injected into C57BL/6 mice at a 1:1 ratio. T-cell homing was analyzed 1 hour after transfer (n = 3 mice per group). Localization of Dock8+/− (red) and Dock8−/− (green) T cells in the spleen was compared 48 hours after transfer. Metallophilic macrophages (blue) were stained with MOMA1 Ab. Scale bar indicates 100 μm. (D) Splenic B220+ B cells were analyzed for the expression of CD21 and CD23 at the age of 10 weeks. The number of CD21+CD23− MZB cells was compared between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− mice (n = 4 mice per group). **P < .01. (E) Serum concentrations of IgM, IgG1, IgG2b, and IgE were compared between 7- to 12-week-old Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− mice (n = 10-11 mice per group). Each symbol represents an individual mouse; small horizontal lines indicate the average. Data are from 9 (A), 8 (B), 3 (C), or 2 (D-E) separate experiments and are expressed as means ± SD with representative flow cytometric profiles.

Effect of DOCK8 deficiency on leukocyte subsets under the steady state. (A-B) Splenocytes (A; n = 10 mice per group) and peripheral LN cells (B; n = 8 mice per group) from 6- to 7-week-old mice were analyzed for the expression of CD4 and CD8 or Mac1 and B220. The numerals in quadrants indicate the percentage of cells in each. The number of each subset of cells was compared between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− mice. **P < .01. (C) Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− T cells were labeled with different fluorescent dyes and IV injected into C57BL/6 mice at a 1:1 ratio. T-cell homing was analyzed 1 hour after transfer (n = 3 mice per group). Localization of Dock8+/− (red) and Dock8−/− (green) T cells in the spleen was compared 48 hours after transfer. Metallophilic macrophages (blue) were stained with MOMA1 Ab. Scale bar indicates 100 μm. (D) Splenic B220+ B cells were analyzed for the expression of CD21 and CD23 at the age of 10 weeks. The number of CD21+CD23− MZB cells was compared between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− mice (n = 4 mice per group). **P < .01. (E) Serum concentrations of IgM, IgG1, IgG2b, and IgE were compared between 7- to 12-week-old Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− mice (n = 10-11 mice per group). Each symbol represents an individual mouse; small horizontal lines indicate the average. Data are from 9 (A), 8 (B), 3 (C), or 2 (D-E) separate experiments and are expressed as means ± SD with representative flow cytometric profiles.

Dock8−/− DCs are defective in T-cell priming

To examine the role of DOCK8 in T-cell immune responses, we immunized Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− mice subcutaneously into the hind footpads with OVA emulsified in CFA. When Dock8+/− CD4+ T cells were prepared from the popliteal LNs at 7 days after immunization, they proliferated vigorously in vitro in response to OVA (Figure 2A). However, such antigen-specific T-cell proliferation was impaired in Dock8−/− mice, resulting in a marked reduction of CD4+ T cells in the popliteal LNs (Figure 2A). Consistent with this finding, OVA-specific IgG Ab production was also impaired in Dock8−/− mice at 14 days after immunization (Figure 2B).

Dock8−/− DCs fail to activate T cells effectively in the draining LNs after subcutaneous injection. (A) Effect of DOCK8 deficiency on T-cell response 7 days after OVA immunization. The number of CD4+ T cells in the popliteal LNs (n = 3 mice per group) and their proliferative response to OVA were compared between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− mice. (B) Serum concentrations of OVA-specific IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgM were compared between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− mice 14 days after immunization (n = 4 mice per group). (C-D) Effect of DOCK8 deficiency in donor T cells (C; n = 8 mice per group) or recipient mice (D; n = 6 mice per group) on proliferation and expansion of the OT-II–transgenic CD4+ T cells was analyzed 72 hours after OVA immunization. PBS was used as a control. (E) Effect of DOCK8 deficiency in BM-derived DCs on proliferation and expansion of the OT-II–transgenic CD4+ T cells was analyzed 72 hours after subcutaneous injection of OVA peptide–pulsed DCs (n = 6 mice per group). In panels C through E, the OT-II–transgenic CD4+ T cells were inoculated 24 hours before immunization or DC transfer. Data are expressed as means ± SD with representative flow cytometric profiles. *P < .05; **P < .01. Data are representative of 4 (A) or 2 (B) independent experiments, and are from 8 (C) or 6 (D-E) separate experiments.

Dock8−/− DCs fail to activate T cells effectively in the draining LNs after subcutaneous injection. (A) Effect of DOCK8 deficiency on T-cell response 7 days after OVA immunization. The number of CD4+ T cells in the popliteal LNs (n = 3 mice per group) and their proliferative response to OVA were compared between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− mice. (B) Serum concentrations of OVA-specific IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgM were compared between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− mice 14 days after immunization (n = 4 mice per group). (C-D) Effect of DOCK8 deficiency in donor T cells (C; n = 8 mice per group) or recipient mice (D; n = 6 mice per group) on proliferation and expansion of the OT-II–transgenic CD4+ T cells was analyzed 72 hours after OVA immunization. PBS was used as a control. (E) Effect of DOCK8 deficiency in BM-derived DCs on proliferation and expansion of the OT-II–transgenic CD4+ T cells was analyzed 72 hours after subcutaneous injection of OVA peptide–pulsed DCs (n = 6 mice per group). In panels C through E, the OT-II–transgenic CD4+ T cells were inoculated 24 hours before immunization or DC transfer. Data are expressed as means ± SD with representative flow cytometric profiles. *P < .05; **P < .01. Data are representative of 4 (A) or 2 (B) independent experiments, and are from 8 (C) or 6 (D-E) separate experiments.

T-cell priming occurs in the draining LNs through interaction with APCs. To determine whether DOCK8 deficiency affects T cells or APCs, we performed transfer experiments using CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells expressing the OVA-specific OT-II TCR. When the transgenic CD4+ T cells with or without DOCK8 expression were IV transferred into C57BL/6 mice, OVA immunization caused only a modest difference between them (Figure 2C). In contrast, the lack of DOCK8 expression in the recipient mice severely impaired the activation and expansion of the transgenic T cells (Figure 2D), suggesting that APC function is primarily affected in the absence of DOCK8. Because DCs are the most potent APCs, we examined DC-mediated T-cell priming directly by injecting OVA peptide–pulsed BM-derived DCs into the footpads. Without immunization, adoptive transfer of Dock8+/− DCs elicited a proliferative response in transgenic CD4+ T cells with up-regulation of CD25 and CD44 expression (Figure 2E and data not shown). However, such T-cell activation was not induced by Dock8−/− DCs, especially when relatively small numbers of DCs were transferred (Figure 2E). These results indicate that DOCK8 expression in DCs is required for T-cell priming during immune responses.

DOCK8 regulates DC trafficking during immune responses

To explore the mechanism through which DOCK8 controls T-cell priming by DCs, we first examined the effect of DOCK8 deficiency on antigen uptake and presentation. Uptake of FITC-labeled OVA and dextran were indistinguishable between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs (Figure 3A). In addition, after incubation with the OVA protein, Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs stimulated OT-II transgenic CD4+ T cells comparably (Figure 3B). These results indicate that neither antigen uptake nor presentation is affected by DOCK8 deficiency.

DOCK8 regulates DC trafficking to the draining LNs during immune responses. (A) Uptake of FITC-OVA and FITC-dextran were compared at 37°C or 4°C between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− BM-derived DCs. (B) After fixation with 1% paraformaldehyde, OVA protein-pulsed Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs were cultured with CD4+ OT-II T cells. (C) Migration of epidermal DCs was induced by applying 200 μL of 1% FITC isomer I onto the shaved abdomen. The frequency of FITC+ MHC class II+ DCs was compared between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− mice. (D) The migration efficiency of Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs to the popliteal LNs was compared 48 hours after injection into footpads of C57BL/6 mice at a 1:1 ratio (n = 3 mice per group). Before assays, DCs were stimulated with or without LPS (200 ng/mL). Data are expressed as means ± SD with representative flow cytometric profiles. **P < .01. Data are representative of 2 (A-B), 4 (C), or 3 (D) independent experiments.

DOCK8 regulates DC trafficking to the draining LNs during immune responses. (A) Uptake of FITC-OVA and FITC-dextran were compared at 37°C or 4°C between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− BM-derived DCs. (B) After fixation with 1% paraformaldehyde, OVA protein-pulsed Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs were cultured with CD4+ OT-II T cells. (C) Migration of epidermal DCs was induced by applying 200 μL of 1% FITC isomer I onto the shaved abdomen. The frequency of FITC+ MHC class II+ DCs was compared between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− mice. (D) The migration efficiency of Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs to the popliteal LNs was compared 48 hours after injection into footpads of C57BL/6 mice at a 1:1 ratio (n = 3 mice per group). Before assays, DCs were stimulated with or without LPS (200 ng/mL). Data are expressed as means ± SD with representative flow cytometric profiles. **P < .01. Data are representative of 2 (A-B), 4 (C), or 3 (D) independent experiments.

We also examined the migration of skin DCs to the draining LNs by painting the skin with FITC. Although the expression level of CCR7 was unchanged between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs (supplemental Figure 3), the number of FITC-positive, MHC class II–expressing DCs were much more reduced in the draining LNs of Dock8−/− mice than in those of Dock8+/− mice (Figure 3C). When Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− BM-derived DCs were labeled with different fluorescent dyes and injected into the footpads of C57BL/6 mice at a 1:1 ratio, the migration efficiency of Dock8−/− DCs to the popliteal LNs was reduced to less than 25% of the Dock8+/− level irrespective of pretreatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Figure 3D). Therefore, DOCK8 plays a key role in DC trafficking to the draining LNs during immune responses.

DOCK8 is required for DC migration in 3D, but not 2D, environments

DC trafficking is a complex process composed of multiple steps, including movement in the dermal interstitium, entry into the lymphatic vessels, and extravasation from the lymphatic system into the LNs.2,3 To determine which step requires DOCK8, we first compared the migration of Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs within dermal tissues. For this purpose, we used “crawl-in” assays in which fluorescently labeled BM-derived DCs were placed on the dermis of ear explants (supplemental Figure 4). After incubation for 90 minutes, the majority of Dock8+/− DCs were localized within the LYVE-1+ lymphatic vessels, whereas Dock8−/− DCs were distributed randomly throughout the tissue (Figure 4A and supplemental Figure 4). Because the perilymphatic basement membrane of initial lymphatics is discontinuous,31 both Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs entered the lymphatic vessel if they could gain access to it (supplemental Videos 1-2). However, single-cell tracking revealed that DOCK8 deficiency reduced the migration velocity of DCs within dermal tissues significantly (Figure 4B), indicating that this step requires DOCK8.

DOCK8 is required for DC migration in 3D, but not 2D, environments. (A) Localization of Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs within the dermis of ear explants after a 90-minute incubation. Scale bar indicates 100 μm. (B) Comparison of the velocity of Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs migrating within the dermis of ear explants. Velocities were determined by analyzing more than 160 cells per group. **P < .01. (C) Migration of LPS-stimulated Dock8+/− (n = 232) and Dock8−/− (n = 194) DCs toward 60 μL of CCL21 source (10 μg/mL) in 3D collagen gels. DC migration was recorded for 120 minutes by time-lapse videomicroscopy. **P < .01. (D) EZ-Taxiscan chemotaxis assay of LPS-stimulated Dock8+/− (n = 47) and Dock8−/− DCs (n = 53) toward 1 μL of CCL21 source (250 μg/mL) on a fibronectin-coated 2D surface. DC migration was recorded for 30 minutes by time-lapse videomicroscopy. (E) Morphology of Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs migrating toward a CCL21 gradient in 3D collagen gels. SYTO12 was used to stain nuclei (green). Elapsed time is presented as minutes:seconds. Scale bar indicates 10 μm. In panels B through D, each box plot exhibits the median (central line within each box), the 25th and 75th percentile values (box ends), and the 10th and 90th percentile values (error bars). Data are representative of 3 (A,C,E) or 2 (D) independent experiments and are from 3 (B) separate experiments.

DOCK8 is required for DC migration in 3D, but not 2D, environments. (A) Localization of Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs within the dermis of ear explants after a 90-minute incubation. Scale bar indicates 100 μm. (B) Comparison of the velocity of Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs migrating within the dermis of ear explants. Velocities were determined by analyzing more than 160 cells per group. **P < .01. (C) Migration of LPS-stimulated Dock8+/− (n = 232) and Dock8−/− (n = 194) DCs toward 60 μL of CCL21 source (10 μg/mL) in 3D collagen gels. DC migration was recorded for 120 minutes by time-lapse videomicroscopy. **P < .01. (D) EZ-Taxiscan chemotaxis assay of LPS-stimulated Dock8+/− (n = 47) and Dock8−/− DCs (n = 53) toward 1 μL of CCL21 source (250 μg/mL) on a fibronectin-coated 2D surface. DC migration was recorded for 30 minutes by time-lapse videomicroscopy. (E) Morphology of Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs migrating toward a CCL21 gradient in 3D collagen gels. SYTO12 was used to stain nuclei (green). Elapsed time is presented as minutes:seconds. Scale bar indicates 10 μm. In panels B through D, each box plot exhibits the median (central line within each box), the 25th and 75th percentile values (box ends), and the 10th and 90th percentile values (error bars). Data are representative of 3 (A,C,E) or 2 (D) independent experiments and are from 3 (B) separate experiments.

The interstitial space of the dermis is dominated by fibrillar arrays of collagen bundles,32 so we used 3D collagen gels to mimic this interstitial microenvironment. When Dock8+/− DCs were exposed to a diffusion gradient of CCL21, they migrated efficiently toward the chemokine source (Figure 4C). However, the chemotactic response of Dock8−/− DCs was also impaired in this setup (Figure 4C). Conversely, DOCK8 deficiency did not affect motility or directionality on 2D surfaces significantly under several conditions tested (Figure 4D and supplemental Figure 5). These results indicate that DOCK8 is selectively required for DC migration in 3D fibrillar environments. To better understand the mechanism by which this occurs, we compared cell morphology by visualizing chemotaxing DCs in 3D collagen gels at high magnification and resolution. Whereas Dock8+/− DCs changed their shape frequently, extending long protrusions in the direction of migration, the majority of Dock8−/− DCs exhibited a round, unpolarized morphology and failed to move effectively in 3D collagen gels (Figure 4E).

DOCK8 is required for DCs to transmigrate through the SCS

LNs are densely packed with lymphocytes and stroma cells, but contain little ECM.33,34 To examine the role of DOCK8 in intranodal DC migration, we injected differently labeled Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs into the footpads of C57BL/6 mice at a 1:3-1:5 ratio and analyzed popliteal LNs using intravital 2-photon microscopy.25,26,35 The migration velocity was unchanged between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs in both the SCS and the parenchyma (Figure 5A). However, 3D reconstitution revealed that, unlike Dock8+/− DCs, Dock8−/− DCs were localized mainly within the 100-μm area from the surface, even at 48 hours after injection (Figure 5B). Because molecules with a molecular weight above 70 kDa are excluded from the parenchyma when injected subcutaneously,36 active cellular movement may be required to pass through the SCS floor. Indeed, Dock8+/− DCs squeezed between the LYVE-1+ sinus lining cells by deforming their shape, whereas such morphological adaptation was impaired in the absence of DOCK8 (Figure 5C and supplemental Video 3). These results indicate that DOCK8 is also required for DCs to enter the LN parenchyma efficiently through the SCS floor.

Dock8−/− DCs fail to effectively transmigrate through the SCS floor. (A-C) Intravital 2-photon microscopy for LPS-stimulated DCs. (A) Velocities in the LN parenchyma and the SCS were compared between Dock8+/− (n = 116 for parenchyma; n = 21 for SCS) and Dock8−/− (n = 48 for parenchyma; n = 20 for SCS) DCs. Each symbol represents an individual DC; small horizontal lines indicate the average. (B) Localization of Dock8+/− (red) and Dock8−/− (blue) DCs in the LNs 48 hours after DC transfer. HEV (green) indicates high endothelial venule. The percentage of cells localized within outer 100 μm was compared between Dock8+/− (n = 658) and Dock8−/− (n = 171) DCs. Data are expressed as means ± SD *P < .05. (C) Morphology of Dock8+/− (green) and Dock8−/− (red) DCs migrating through the SCS floor (light blue). The length of cells located at the SCS floor was compared between Dock8+/− (n = 65) and Dock8−/− (n = 79) DCs. **P < .01. Elapsed time is presented as minutes:seconds. Each box plot exhibits the median (central line within each box), the 25th and 75th percentile values (box ends), and the 10th and 90th percentile values (error bars). In panels A through C, data are from 3 separate experiments.

Dock8−/− DCs fail to effectively transmigrate through the SCS floor. (A-C) Intravital 2-photon microscopy for LPS-stimulated DCs. (A) Velocities in the LN parenchyma and the SCS were compared between Dock8+/− (n = 116 for parenchyma; n = 21 for SCS) and Dock8−/− (n = 48 for parenchyma; n = 20 for SCS) DCs. Each symbol represents an individual DC; small horizontal lines indicate the average. (B) Localization of Dock8+/− (red) and Dock8−/− (blue) DCs in the LNs 48 hours after DC transfer. HEV (green) indicates high endothelial venule. The percentage of cells localized within outer 100 μm was compared between Dock8+/− (n = 658) and Dock8−/− (n = 171) DCs. Data are expressed as means ± SD *P < .05. (C) Morphology of Dock8+/− (green) and Dock8−/− (red) DCs migrating through the SCS floor (light blue). The length of cells located at the SCS floor was compared between Dock8+/− (n = 65) and Dock8−/− (n = 79) DCs. **P < .01. Elapsed time is presented as minutes:seconds. Each box plot exhibits the median (central line within each box), the 25th and 75th percentile values (box ends), and the 10th and 90th percentile values (error bars). In panels A through C, data are from 3 separate experiments.

DOCK8 acts as a Cdc42-specific GEF

DOCK proteins are classified into 4 subfamilies (DOCK-A, DOCK-B, DOCK-C, and DOCK-D) based on their structures, all of which contain the DHR-2 domains to mediate the GTP-GDP exchange reaction for small GTPases.15,22,23 To address the substrate specificity of DOCK8, we expressed DOCK8 in human embryonic kidney 293T cells and analyzed its binding to the Rho family of GTPases. Although DOCK8 did not show any binding to RhoA and Rac1, DOCK8 bound to the nucleotide-free Cdc42 in a manner dependent on the DHR-2 domain (Figure 6A). DOCK2 is a major Rac GEF that controls migration of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasmacytoid DCs.24,37,38 Compared with the Rac GEF activity of DOCK2, the catalytic activity of DOCK8 was less robust; nonetheless, the bacterially expressed DOCK8 DHR-2 clearly mediated the GTP-GDP exchange reaction for Cdc42 (Figure 6B), indicating that DOCK8 functions as a Cdc42-specific GEF.

DOCK8 is a Cdc42-specific GEF. (A) Extracts from human embryonic kidney 293T cells expressing HA-tagged DOCK8, DOCK8 ΔDHR-2, or DOCK2 were pulled down with GST-fusion proteins encoding Cdc42, Rac1, or RhoA. Assays were done in Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20 supplemented with 10mM EDTA (E) or 10mM MgCl2 plus 30μM GTPγS (M). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) Recombinant DOCK8 DHR-2 and DOCK2 DHR-2 proteins were analyzed for their GEF activities toward Cdc42 (top panels) or Rac1 (bottom panels) using mant-GTP. RFU indicates relative fluorescence units. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) Overall structure of the complex between DOCK8 DHR-2 and Cdc42. DOCK8 and Cdc42 are colored salmon and green, respectively; the switch I region of Cdc42 is shown in black. (D-E) Rac1 bound to DOCK2 DHR-2 (Protein Data Bank accession code 3B13) and Cdc42 bound to DOCK9 DHR-2 (Protein Data Bank accession code 2WM9) are superposed onto the Cdc42-binding site of DOCK8 DHR-2. Rac1 is colored yellow; Cdc42 bound to DOCK8 is light green; Cdc42 bound to DOCK9 is dark green; and DOCK8, DOCK9, and DOCK2 are salmon, purple, and blue, respectively. The arrow in panel E indicates the different location of the DHR-2 lobe B in DOCK2 compared with those in DOCK8 and DOCK9.

DOCK8 is a Cdc42-specific GEF. (A) Extracts from human embryonic kidney 293T cells expressing HA-tagged DOCK8, DOCK8 ΔDHR-2, or DOCK2 were pulled down with GST-fusion proteins encoding Cdc42, Rac1, or RhoA. Assays were done in Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20 supplemented with 10mM EDTA (E) or 10mM MgCl2 plus 30μM GTPγS (M). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) Recombinant DOCK8 DHR-2 and DOCK2 DHR-2 proteins were analyzed for their GEF activities toward Cdc42 (top panels) or Rac1 (bottom panels) using mant-GTP. RFU indicates relative fluorescence units. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) Overall structure of the complex between DOCK8 DHR-2 and Cdc42. DOCK8 and Cdc42 are colored salmon and green, respectively; the switch I region of Cdc42 is shown in black. (D-E) Rac1 bound to DOCK2 DHR-2 (Protein Data Bank accession code 3B13) and Cdc42 bound to DOCK9 DHR-2 (Protein Data Bank accession code 2WM9) are superposed onto the Cdc42-binding site of DOCK8 DHR-2. Rac1 is colored yellow; Cdc42 bound to DOCK8 is light green; Cdc42 bound to DOCK9 is dark green; and DOCK8, DOCK9, and DOCK2 are salmon, purple, and blue, respectively. The arrow in panel E indicates the different location of the DHR-2 lobe B in DOCK2 compared with those in DOCK8 and DOCK9.

DOCK-C subfamily proteins (DOCK6-8) partially conserve the Cdc42-interacting residues of DOCK939 and the Rac1-interacting residues of DOCK2.40 To understand the mechanism underlying the Cdc42 specificity of DOCK8, we performed X-crystallographic analysis of the complex between the DOCK8 DHR-2 domain and the dominant-negative T17N mutant of Cdc42 (supplemental Table 1). Two lobes (lobes B and C) of DOCK8 DHR-2 generate a cooperative interface with Cdc42 (Figure 6C) in a manner similar to DOCK9 DHR-2.39 Based on the DOCK6 structural model, it was predicted that Met1932 of DOCK6 would be incompatible with the aromatic side chain at position 56 (Phe, Tyr, or Trp) that is conserved in nearly all of the Rho family of GTPases.40 However, the DOCK8 DHR-2·Cdc42 complex structure revealed that DOCK8 Met1976, corresponding to Met1932 of DOCK6, assumes a bent side-chain conformation and thereby avoids the putative steric hindrance with the Phe56 side chain of Cdc42 (Figure 6D). When the structure of Rac1 was taken from that in complex with DOCK2 DHR-2 and superposed onto that of Cdc42 in complex with DOCK8 DHR-2 (Figure 6D), it was found that Trp56 of Rac1 is larger than Phe and is therefore incompatible with Tyr2043 of DOCK8. Conversely, DOCK8 Ile1820 and DOCK9 Leu1785 interact with Thr43 of Cdc42 in a similar manner, so the DHR-2 lobe B binds properly to the switch I of Cdc42 (Figure 6E and supplemental Figure 6). Therefore, the DOCK8 residues responsible for its specificity for Cdc42, but not Rac1, have been established.

DOCK8 regulates interstitial DC migration by controlling Cdc42 activity spatially

Having found that DOCK8 mediates Cdc42 activation through the DHR-2 domain, we also investigated whether this domain is functionally important for the 3D migration of leukocytes using the BW5147α−β− thymoma cell line that lacks the expression of both DOCK2 and DOCK8.37 Because Rac activation confers the driving force for movement, the expression of DOCK2 improved the motility of BW5147α−β− cells in 3D collagen gels (Figure 7A); more importantly, the migration velocity of BW5147α−β− cells in 3D collagen gels was increased markedly by coexpressing DOCK8 (Figure 7A). However, such a synergistic effect was completely abrogated when the DOCK8 DHR-2 domain was deleted (Figure 7A), suggesting that DOCK8 regulates 3D leukocyte migration as a Cdc42 GEF.

DOCK8 controls Cdc42 activation spatially during DC migration in 3D environments. (A) Migration of BW5147α−β− cells stably expressing DOCK8, DOCK8 ΔDHR-2, and/or DOCK2 in 3D collagen gels was compared (n = 101-128 per group). Each box plot exhibits the median (central line within each box), the 25th and 75th percentile values (box ends), and the 10th and 90th percentile values (error bars). **P < .01. (B) Effect of DOCK8 deficiency on CCL21-induced activation of Cdc42, Rac1, and RhoA in DCs. (C) Localization of HA-tagged DOCK8 and βPIX in BW5147α−β− cells. Concanavalin A (green) and DAPI (blue) were used to stain plasma membrane and nuclei, respectively. Scale bar indicates 5 μm. (D) Subcellular localization of DOCK8 and βPIX in DCs. Membrane (M) and cytosol (C) fractions were analyzed by immunoblot. TCL indicates total cell lysates. (E) Effect of DOCK8 deficiency on localization of activated Cdc42 in DCs migrating in 3D collagen gels. Images were taken every 1 minute and the emission ratio of 527 nm/475 nm (FRET/CFP ratio) was used to represent the FRET efficiency. The FRET/CFP ratios at the plasma membrane (PM) and the cytoplasm (CP) were normalized by dividing by the lowest value in the cells and were compared between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs (n = 10 cells per group). Scale bar indicates 5 μm. Data are expressed as means ± SD. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (A-D) or are from 10 separate experiments (E).

DOCK8 controls Cdc42 activation spatially during DC migration in 3D environments. (A) Migration of BW5147α−β− cells stably expressing DOCK8, DOCK8 ΔDHR-2, and/or DOCK2 in 3D collagen gels was compared (n = 101-128 per group). Each box plot exhibits the median (central line within each box), the 25th and 75th percentile values (box ends), and the 10th and 90th percentile values (error bars). **P < .01. (B) Effect of DOCK8 deficiency on CCL21-induced activation of Cdc42, Rac1, and RhoA in DCs. (C) Localization of HA-tagged DOCK8 and βPIX in BW5147α−β− cells. Concanavalin A (green) and DAPI (blue) were used to stain plasma membrane and nuclei, respectively. Scale bar indicates 5 μm. (D) Subcellular localization of DOCK8 and βPIX in DCs. Membrane (M) and cytosol (C) fractions were analyzed by immunoblot. TCL indicates total cell lysates. (E) Effect of DOCK8 deficiency on localization of activated Cdc42 in DCs migrating in 3D collagen gels. Images were taken every 1 minute and the emission ratio of 527 nm/475 nm (FRET/CFP ratio) was used to represent the FRET efficiency. The FRET/CFP ratios at the plasma membrane (PM) and the cytoplasm (CP) were normalized by dividing by the lowest value in the cells and were compared between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs (n = 10 cells per group). Scale bar indicates 5 μm. Data are expressed as means ± SD. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (A-D) or are from 10 separate experiments (E).

This finding led us to examine how DOCK8 deficiency affects Cdc42 activation during DC migration. Although Cdc42, along with Rac1 and RhoA, were activated in DCs in response to CCL21, the level of the GTP-bound Cdc42 was unchanged between Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs (Figure 7B), probably because of functional compensation by other GEFs such as βPIX.41 When HA-tagged βPIX was expressed in BW5147α−β− cells, it was localized mainly in the intracytoplasmic vesicles (Figure 7C). In contrast, HA-tagged DOCK8 accumulated preferentially at the plasma membrane (Figure 7C). Similar results were obtained when the subcellular localization of DOCK8 in DCs was analyzed biochemically (Figure 7D). To examine whether DOCK8 deficiency alters the site of Cdc42 activation, we retrovirally transduced Dock8+/− and Dock8−/− DCs to express the FRET-based biosensor Raichu-Cdc42, which can be used to monitor Cdc42 activation at the membrane.42 Comparison of FRET efficiency in Dock8+/− DCs migrating in 3D collagen gels revealed that Cdc42 was predominantly activated at the leading-edge membrane (Figure 7E). In the case of Dock8−/− DCs, however, Cdc42 activation was the most prominent in the central, not the peripheral, region (Figure 7E). These results indicate that DOCK8 is important for localized activation of Cdc42 at the plasma membrane.

Discussion

Although DOCK8 plays a key role in long-term memory in B cells and CD8+ T cells,19-21 the role of DOCK8 in DCs was unknown. In the present study, we have shown that DOCK8 critically regulates interstitial DC migration during immune responses. By generating knockout mice, we found that, in the absence of DOCK8, DCs failed to accumulate in the LN parenchyma for T-cell priming. DOCK8 expression was dispensable for DC migration on 2D surfaces. However, Dock8−/− DCs exhibited a migration defect in the fibrillar networks of collagen matrices in vitro and the dermis in vivo. Therefore, our results reveal a previously unknown function of DOCK8 in DCs.

We found that DOCK8 binds specifically to nucleotide-free Cdc42 through the DHR-2 domain and mediates the GTP-GDP exchange reaction for Cdc42. These results indicate clearly that DOCK8 functions as a Cdc42-specific GEF. By inactivating global Cdc42 activity genetically or functionally, it has been reported previously that Cdc42 regulates various cellular functions in DCs, including endocytosis, antigen presentation, and T-cell activation.43-45 However, none of these functions was impaired in the absence of DOCK8, probably because the effect of DOCK8-mediated Cdc42 activation is limited to membrane dynamics at the cell periphery. Consistent with this idea, DOCK8 deficiency did not affect global Cdc42 activity. However, Cdc42 activation at the leading-edge membrane was impaired in Dock8−/− DCs, resulting in their inability to extend long protrusions in the direction of migration. This defect is likely to preclude Dock8−/− DCs from probing the space and squeezing through narrow gaps of fibrillar ECM. The critical role of DOCK8 in morphological adaptation may explain why DOCK8 is required for DC migration in 3D, but not 2D, environments.

Another important feature of Dock8−/− DCs was a defect in transmigrating through the SCS floor. Before entering the LN parenchyma, DCs must pass through the tight layer of sinus-lining cells by deforming their shape. This process was impaired in the absence of DOCK8 and, as a result, considerable numbers of Dock8−/− DCs were retained in the SCS for longer periods of time. This distribution pattern is apparently similar to that of intralymphatically injected CCR7-deficient (Ccr7−/−) DCs.46 However, whereas Ccr7−/− DCs are less motile than wild-type DCs in the LN parenchyma,46 DOCK8 deficiency did not affect the migration velocity of DCs in the same area. The interstitial space of the LN is a cell-packed environment and contains little ECM33,34 ; therefore, the relatively loose environment compared with that of the dermis and the collagen gels would have enabled Dock8−/− DCs to move smoothly within the LN parenchyma. This “mesh size”–dependent effect also shows that DOCK8 is important in morphological adaptation during interstitial DC migration.

In summary, we have shown in the present study that DOCK8 is a Cdc42-specific GEF and regulates interstitial DC migration by controlling Cdc42 activation spatially. Our results define a novel regulatory mechanism for interstitial DC migration, and provide mechanistic insight into the T-cell dysfunction associated with DOCK8 deficiency in humans.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. Matsuda (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) for the plasmid encoding Raichu-Cdc42.

This work was supported by the Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology program (Y.F., T.K., and S.Y.); the Strategic Japanese-Swiss Cooperative Program of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (Y.F. and J.V.S.); the Targeted Proteins Research Project (Y.F. and S.Y.); Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (Y.F. and T.K.); Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Y.F. and Y.T.); the SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation (Y.T.); and the Daiichi-Sankyo Foundation of Life Science (Y.T.).

Authorship

Contribution: Y.H., Y.T., and M.T. performed the functional and biochemical experiments, analyzed the data, and contributed to manuscript preparation; M.P., K.H., T. Katakai, J.V.S., and T. Kinashi performed the 2-photon microscopic analyses; K.H.-S., M.K.-N., T.N., M.S., and S.Y. performed the X-ray crystallographic analysis; X.D., T.U., A.N., and F.S. contributed to functional or biochemical experiments; S.Y., J.V.S., and T. Kinashi interpreted the data; and Y.F. conceived the study, designed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yoshinori Fukui, Division of Immunogenetics, Department of Immunobiology and Neuroscience, Medical Institute of Bioregulation, Kyushu University, Fukuoka 812-8582, Japan; e-mail: fukui@bioreg.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

Y.H. and Y.T. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal