Abstract

To investigate the role of Aire in thymic selection, we examined the cellular requirements for generation of ovalbumin (OVA)–specific CD4 and CD8 T cells in mice expressing OVA under the control of the rat insulin promoter. Aire deficiency reduced the number of mature single-positive OVA-specific CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in the thymus, independent of OVA expression. Importantly, it also contributed in 2 ways to OVA-dependent negative selection depending on the T-cell type. Aire-dependent negative selection of OVA-specific CD8 T cells correlated with Aire-regulated expression of OVA. By contrast, for OVA-specific CD4 T cells, Aire affected tolerance induction by a mechanism that operated independent of the level of OVA expression, controlling access of antigen presenting cells to medullary thymic epithelial cell (mTEC)–expressed OVA. This study supports the view that one mechanism by which Aire controls thymic negative selection is by regulating the indirect presentation of mTEC-derived antigens by thymic dendritic cells. It also indicates that mTECs can mediate tolerance by direct presentation of Aire-regulated antigens to both CD4 and CD8 T cells.

Introduction

For many years investigators noted the ectopic expression of tissue-specific antigens (TSAs) in the thymus of normal and transgenic mice1,2 and other species.3,4 Although this observation was a fascinating one, the true impact of thymic expression of TSAs was not fully appreciated until the generation and analysis of Aire-deficient mice.5-7 These studies were prompted by the discovery of a recessive autoimmune disease in humans referred to as autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type I or autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy.8,9 This disease is associated with circulating tissue-specific autoantibodies that contribute to the destruction of target organs, mainly endocrine glands.10-12 The first symptoms that typically appear during early childhood include chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, hypoparathyroidism, and primary adrenocortical failure. In adulthood, patients develop endocrine autoimmune diseases, such as gonadal atrophy, type 1 diabetes, hypothyroidism, and hepatitis. In addition, several ectodermic diseases may arise.10

This disease was mapped to the AIRE locus, where several mutations have now been reported.13 The generation of Aire-deficient mice revealed 2 important observations: first, that many TSAs shown to have ectopic thymic expression were regulated by Aire and, second, that mice deficient in Aire were prone to autoimmune disease.14 The initial report by Anderson et al5 suggested that Aire controlled self-tolerance by enabling ectopic expression of TSAs in the medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs), although not all TSA genes appeared to be controlled by Aire. The ability of Aire to control thymic tolerance by regulating expression of TSAs was formally demonstrated by use of the RIP-HEL transgenic system, where the model antigen hen egg lysozyme (HEL) was expressed under the control of the rat insulin promoter (RIP). Liston et al15 showed that Aire regulated expression of HEL in the thymus and that this was essential to delete HEL-specific thymocytes and limit autoimmunity. Using a transgenic model, Aschenbrenner et al16 have recently provided evidence that Aire-expressing mTECs may also participate in the thymic selection of regulatory T cells, although others have reported no effect.14

The view that AIRE may have functions in addition to the simple regulation of TSA expression was first raised by evidence that tolerance to a model self-antigen was lost in Aire-deficient mice despite a failure of Aire to regulate its thymic expression.7,17 In one of these studies investigators demonstrated that thymic deletion of both CD4 and CD8 T cells specific for a membrane-bound form of ovalbumin (mOVA) was impaired in Aire-deficient mice expressing mOVA under the control of RIP (RIP-mOVA mice), despite equivalent expression of mOVA mRNA in mTECs. To explain these observations, Mathis and colleagues14 provided some evidence that genes associated with antigen presentation were regulated by Aire in mTEC and that Aire-deficient mTECs were inefficient at MHC I–restricted antigen presentation. In a subsequent study, Gray et al18 have shown that Aire also affects the development of mTECs, with increased numbers, and reduced turnover, of this population in Aire-deficient mice. Aire protein is expressed in the most mature form of mTECs, which are likely to be the predominant antigen-presenting population because they express the greatest levels of MHC II and costimulatory molecules. Gray et al18 provided evidence that Aire expression in a cell line was able to promote apoptosis, suggesting that Aire may regulate mTEC numbers by controlling cell death.

The authors of the aforementioned studies suggested several possible roles for Aire in the control of thymic tolerance, and the complexity of this process was further emphasized by the variation in autoimmune phenotypes when Aire deficiency was examined in several different genetic backgrounds.19 To further investigate the role of Aire in self-tolerance, we generated Aire-deficient mice on a pure B6 background using B6 ES cells.20 These mice were crossed to transgenic lines expressing either a secreted or a membrane-bound form of OVA under the control of the rat insulin promoter. We then used OVA-specific TCR transgenic mice to follow thymic selection and to dissect the various contributions of Aire to this process. Our studies highlight a role for Aire in controlling the transfer of antigen from mTECs to dendritic cells (DCs) as well as its role in regulation of antigen expression for direct presentation by mTECs.

Methods

Mice

BM chimeras

BM chimeras were generated as previously described23 and left 6 weeks before analysis.

Epithelial cell and DC purification

TECs were enriched from the thymus as described.24 In brief, 10-12 thymi in MT-RPMI were briefly agitated with a wide-bore glass pipette and then subjected to enzymatic digestion in 5 mL of 0.125% (wt/vol) collagenase D with 0.1% (wt/vol) DNAse I (Boehringer) at 37°C for 15 minutes. Cells released into suspension were removed after larger thymic fragments had settled. This was repeated 3-4 times with fresh media. In the final digest, collagenase D was replaced with trypsin. Each cell isolation was counted and the final 2 or 3 enrichments pooled. A negative depletion was performed to enrich for CD45− cells with the use of CD45 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and the AutoMACS system (Miltenyi Biotec). Purity was > 90%. Cells were stained with Ly51-FITC (clone 6C3), MHC II-PE (clone M5/114.15.2), and CD45-APC (clone 30F11) mAbs, and CD45− MHC IIhigh Ly51lo cells (mTECs) were sorted on a FACSAria instrument (Becton Dickinson). DCs were isolated as previously described.25

Flow cytometric analysis

Fluorescent-labeled thymocyte preparations were analyzed on a LSR I instrument (BD Biosciences). Cells were labeled with anti-CD4 FITC (GK1.5), anti-CD25 PE (PC61.5), anti-Vα2 biotin (1320.1), and anti-CD8 APC (clone 53-6.7), followed by Streptavidin-PerCp5.5. Dead cells were eliminated by the use of Hoechst 33342 staining (Sigma-Aldrich) and cell numbers determined with Sphero beads (BD Biosciences) as previously described.23

DC were stained with mAbs to CD11c (N418-PECy7), CD45RA (14.8-allophycocyanin), CD8 (YTS169.4-PE), and signal regulatory protein-α (p84-biotin), followed by streptavidin-PerCP-Cy5.5. FITC-conjugated mAbs were used to stain MHC II (M5/114.15.2) or CD80 (16-10A1) or CD86 (GL1). DC preparations were analyzed on a LSR II (BD Biosciences).

Quantitative real-time PCR

RNA was extracted from sorted mTECs and DCs by use of the RNeasy Micro Kit, which included an on column DNase digest (QIAGEN). Reverse transcription was performed with SuperScript III RNase H-Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) with random primers (Promega). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed by use of the Roche LightCycler 480 System with the following primers designed by use of the Universal ProbeLibrary assay design center: Hprt: F-tcctcctcagaccgctttt, R-cctggttcatcatcgctaatc, probe #95; Aire: F-tgctagtcacgaccctgttct, R-ggatgccgtcaaatgagtg, probe #109; Ins2: F-gaagtggaggacccacaagt, R-agtgccaaggtctgaaggtc, probe #32; Spna2: F-gctagtcactatgcctcagatgaa R-aagctcccacagctccag, probe #91; and OVA F-gctatgggcattactgacgtg, R-tgctgaggagatgccagac, probe #41. All quantitative RT-PCRs were prepared in 10 μL with final concentrations of 1× LightCycler 480 Probes Master, 200nM forward and reverse primers, and 100nM Universal ProbeLibrary probe, by use of the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 10 minutes, 45 cycles of 95°C (10 seconds) and 60°C (30 seconds), 40°C (1 minute) to cool. Direct detection of PCR products was monitored by measuring the increase in fluorescence by the LightCycler 480 quantification software. Relative expression was calculated by use of the 2–ΔΔCt method. For chemokine qRT-PCR: Crossing-point values were calculated by use of the second derivative maximum method performed by the LightCycler 480 quantification software. Serially diluted cDNA was used to construct a 4-point standard curve for each quantitative RT-PCR assay. The starting quantity (in arbitrary units) of cDNA for each gene was then calculated as a linear function of the logarithmic concentration and crossing point. The starting quantity of each target gene was normalized to the starting quantity of housekeeping gene Hprt for each sample. Results are shown relative to wild-type (WT). Data shown are mean ± SE of 3 biological replicates. Primer sequences are as follows:

Ccl1: tcccctgaagtttatccagtg; cagctttctctacctttgttcagc

Ccl3: tgcaaccaagtcttctcagc; ggaatcttccggctgtagg

Ccl6: ccttgtggctgtccttgg; gcgacgatcttctttttcca

Ccl7: ttctgtgcctgctgctcata; ttgacatagcagcatgtggat

Ccl8: ttctttgcctgctgctcata; gcaggtgactggagccttat

Ccl9: tgggcccagatcacacat; tgtgaaacatttcaatttcaagc

Ccl11: cacggtcacttccttcacct; tggggatcttcttactggtca

Ccl17: tgcttctggggacttttctg; gaatggcccctttgaagtaa

Cxcl4: cggttccccagctcatag; tgacatttaggcagctgatacc

Cxcl13: catagatcggattcaagttacgc; cacacatataactttcttcatcttggt

Cxcl15: tgctcaaggctggtccat; gacatcgtagctcttgagtgtca

Ccl25: gagtgccaccctaggtcatc; ccagctggtgcttactctga

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was evaluated using the 2-tailed Student t test for 2 groups. P values ≤ .05 were considered significant (*P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001).

Illumina BeadChip expression arrays

RNA from Aire+/+ and Aire−/− mTECs was isolated by the use of an RNeasy Minikit (QIAGEN), including an on column DNase digest. Total RNA quality and quantity were ascertained by use of the Agilent Bioanalyser 2100 with of the NanoChip protocol. A total of 50-500 ng of RNA was labeled with the Ambion Total Prep RNA amplification kit. A total of 1.5 μg of labeled cRNA was then prepared for hybridization to the Illumina Mouse-6 Expression Beadchip (Version 1.1) by preparing a probe cocktail (cRNA at 0.05 μg/μL) that included GEX-HYB Hybridization Buffer. A total hybridization volume of 30 μL was prepared for each sample and loaded into a single array on the Illumina Mouse-6 Expression Beadchip (Version 1.1). The chip was hybridized at 58°C for 16 hours in an oven with a rocking platform. After hybridization, the chip was washed by the use of the appropriate protocols as outlined in the Illumina manual. On completion of the washing, the chips were then coupled with Cy3 and scanned in the Illumina BeadArray Reader. The scanner operating software, BeadStudio, converted the signal on the array into a TXT file for analysis.

Microarray analysis used the lumi26 and limma packages of Bioconductor.27 Expression data were background corrected with the use of negative control probes followed by variance stabilizing transformation28 and quantile normalization. Three Aire−/− and 3 WT replicates were analyzed as part of a larger experiment, including 2 other knockout variants on the same cell type. Significant differentially expressed genes were identified as previously described,20 taking into account beadchip and sex effects. All microarray data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE28393 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE28393).

Results

Aire affects the proportion of single-positive thymocytes

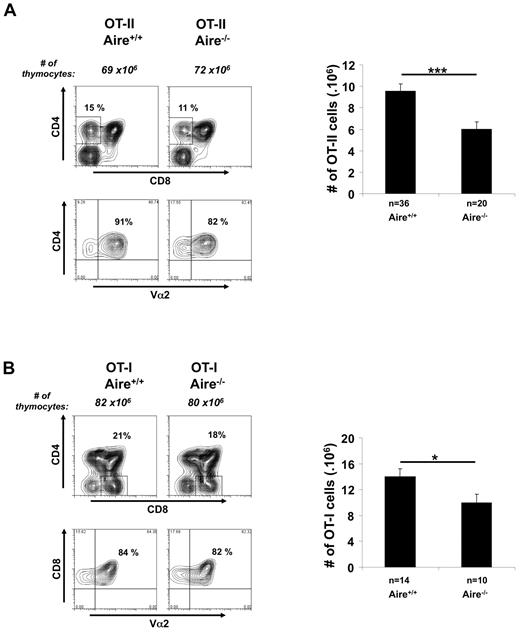

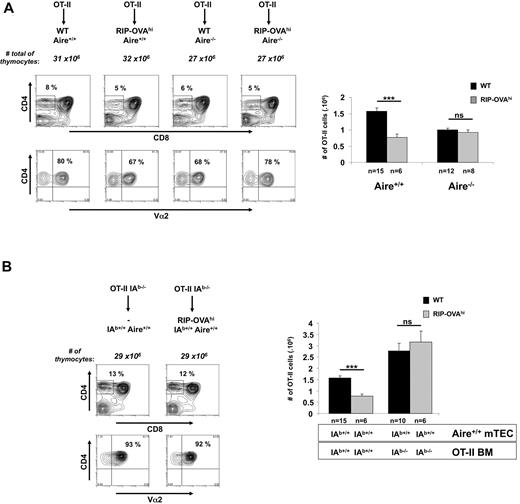

To study the role of Aire in thymic selection, OVA-specific MHC I-restricted OT-I mice and MHC II-restricted OT-II mice were crossed to Aire-deficient mice, and at 3 weeks of age their thymocytes were examined for expression of CD4, CD8, and the transgenic TCR α-chain, Vα2 (Figure 1). Analyzing thymic profiles before weaning reduced mouse housing requirements and any potential effects of Aire-associated autoimmunity. Aire deficiency had little effect on the overall profile of expression of these molecules or on the number of double-negative and double-positive thymocytes, but there was a significant although small reduction in mature single-positive (SP) thymocytes generated for each transgenic. These findings suggest that Aire expression has a mild impact on the number of SP thymocytes normally found in TCR transgenic thymii. This impact may be through effects on positive selection, survival, or migration of SP thymocytes.

Aire affects the number of SP thymocytes. Thymocytes (3-week-old mice) generated by crossing (A) OT-II.Aire+/− or (B) OT-I.Aire+/− mice to nontransgenic Aire+/− mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR, that is, (A) CD4+CD8−Vα2+ cells or (B) CD4−CD8+Vα2+ cells. Contour plots show a representative experiment. Histograms show the mean ± SEM for each group. n = number of mice pooled from several experiments. Significance relative to WT: *P ≤ .05; ***P ≤ .001.

Aire affects the number of SP thymocytes. Thymocytes (3-week-old mice) generated by crossing (A) OT-II.Aire+/− or (B) OT-I.Aire+/− mice to nontransgenic Aire+/− mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR, that is, (A) CD4+CD8−Vα2+ cells or (B) CD4−CD8+Vα2+ cells. Contour plots show a representative experiment. Histograms show the mean ± SEM for each group. n = number of mice pooled from several experiments. Significance relative to WT: *P ≤ .05; ***P ≤ .001.

Both mTECs and DCs have been reported to express Aire, although expression by DCs is vastly inferior.29 To test whether Aire expression by mTEC alone could affect the proportion of SP thymocytes, we generated chimeric mice in which BM from Aire-sufficient OT-I or OT-II mice was injected into lethally irradiated Aire-deficient mice (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). This showed a similar defect in SP cell numbers, indicating that a lack of Aire expression by mTEC alone could cause this effect. A similar outcome in BM chimeras was noted for HEL-specific 3A9 cells (supplemental Figure 2), confirming earlier observations.5,15 These data are consistent with a defect reported for the maturation of SP nontransgenic thymocytes in Aire-deficient mice.30

Aire regulates deletion in RIP-mOVA mice

RIP-mOVA mice were used previously to examine both the role of Aire and the cellular requirements for thymic negative selection.17,21 These mice ectopically express mOVA in the thymus,21 leading to deletion of OT-I and OT-II cells.17 Aire was shown to mediate such deletion by a mechanism that was independent of regulating antigen expression.17 Furthermore, although OT-I cells depended on antigen presentation by mTEC for deletion, OT-II cells were entirely dependent on indirect presentation by DC.31 We have repeated several of these studies using our Aire-deficient mice on a pure B6 background and have come to somewhat different conclusions.

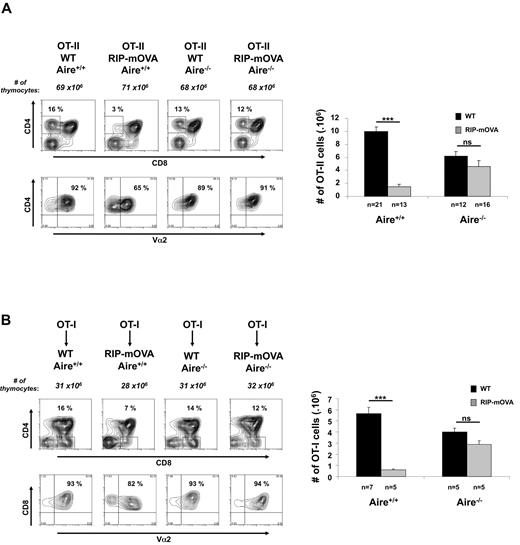

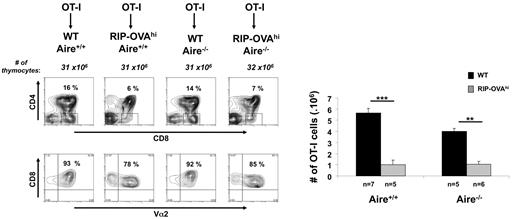

OT-II mice were crossed to RIP-mOVA mice and Aire deficiency introduced by additional crossing. Because of the effect of Aire on the proportion of SP cells (Figure 1), it was essential to examine negative selection in mice that have the same constraints on SP thymocyte numbers. Although RIP-mOVA mice expressing Aire showed efficient thymic deletion of OT-II cells, Aire deficiency almost completely abolished deletion (Figure 2A). These studies confirmed a role for Aire in thymic deletion of T cells specific for TSAs,15 and that in particular OT-II deletion in RIP-mOVA mice was Aire dependent.17

Aire regulates negative selection in RIP-mOVA mice. (A) Thymocytes (3-week-old mice) generated by crossing OT-II.Aire+/− to RIP-mOVA.Aire+/− mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4+CD8−Vα2+ cells, right). (B) Thymocytes (6 weeks postreconstitution) from chimeric mice generated by reconstituting wt.Aire+/+, wt.Aire−/−, RIP-mOVA.Aire+/+, or RIP-mOVA.Aire−/− mice with OT-I BM were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4−CD8+Vα2+ cells, right). Representative contour plots were not all from the same experiment: Aire+/+ groups are matched, as are Aire−/− groups. Histograms show the mean ± SEM for each group. n = number of mice pooled from several experiments. Figures 2B and 6 share the same groups lacking expression of the RIP transgene. Significance relative to WT: ***P ≤ .001; ns indicates not significant.

Aire regulates negative selection in RIP-mOVA mice. (A) Thymocytes (3-week-old mice) generated by crossing OT-II.Aire+/− to RIP-mOVA.Aire+/− mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4+CD8−Vα2+ cells, right). (B) Thymocytes (6 weeks postreconstitution) from chimeric mice generated by reconstituting wt.Aire+/+, wt.Aire−/−, RIP-mOVA.Aire+/+, or RIP-mOVA.Aire−/− mice with OT-I BM were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4−CD8+Vα2+ cells, right). Representative contour plots were not all from the same experiment: Aire+/+ groups are matched, as are Aire−/− groups. Histograms show the mean ± SEM for each group. n = number of mice pooled from several experiments. Figures 2B and 6 share the same groups lacking expression of the RIP transgene. Significance relative to WT: ***P ≤ .001; ns indicates not significant.

To examine the effect of Aire on deletion of OT-I cells, we did not cross OT-I to RIP-mOVA mice because in our colony this combination yielded a reduced proportion of double transgenic mice, even when Aire-sufficient, that is, only 34% (17/50) when the expected Mendelian ratio was 50%, with virtually all double transgenic pups diabetic by weaning, that is, 88% (15/17). This combination was therefore examined by the use of chimeric mice in which OT-I BM was injected into WT or Aire-deficient RIP-mOVA or B6 mice (Figure 2B). Here, OT-I cells were deleted in OT-I→RIP-mOVA chimeras expressing Aire, and deletion was largely impaired in chimeras in which RIP-mOVA were Aire deficient. Identical findings were evident for OT-II→RIP-mOVA chimeras (supplemental Figure 3). These data confirmed that Aire expression was important for the deletion of both OT-I and OT-II cells in RIP-mOVA mice.17 Because all aforementioned BM donors expressed Aire, these results further suggested that regulation of deletion was associated with Aire expression in mTEC.

mOVA expression is partially regulated by Aire

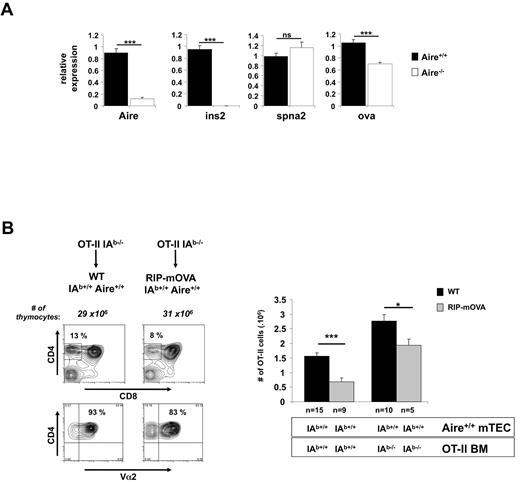

To examine the basis for impaired negative selection in Aire-deficient RIP-mOVA mice, we used real-time PCR to examine expression of mOVA and several other genes in CD45− thymic epithelial cells. Independent experiments showed that our method of preparation strongly enriched for mTEC (63% ± 8% for wild-type mice and 59% ± 6% for Aire-deficient mice; supplemental Figure 4), which are the cell type that express Aire. When normalized to Hprt, mOVA mRNA showed a 30% reduction in Aire-deficient hosts (Figure 3A). This difference is likely because of a reduction in mTEC expression of OVA but could be influenced by expression in non-mTEC. Our observed reduction in mOVA expression in Aire-deficient mice contrasts the lack of Aire regulation of mOVA originally reported by Anderson et al17 but is consistent with more recent findings by some of these authors.32 Insulin and Spna2 gene expression were confirmed as Aire-dependent and -independent, respectively. Autoimmune outcome has been shown to be sensitive to small changes in antigen expression within the thymus in both animal models33-35 and humans.36-38 Thus, a 30% reduction in mOVA mRNA could be responsible for the lack of deletion of both OT-I and OT-II cells in Aire-deficient RIP-mOVA mice, challenging alternative explanations.17

RIP-mOVA mTEC show Aire-dependent regulation of mOVA and directly cause deletion of OT-II cells. (A) Aire regulates mOVA mRNA expression in RIP-mOVA transgenic mice. Relative expression of Aire, Ins2, Spna2, and OVA was determined by quantitative-real time PCR on cDNA prepared from CD45−-enriched thymic cells. Expression values are shown relative to WT after normalization to Hprt. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. A total of 6-10 individual thymi were pooled per experiment. Significance relative to WT: ***P ≤ .001; ns indicates not significant. (B) mTEC are able to present OVA on MHC II. Lethally irradiated 8-week-old B6 or RIP-mOVA mice were grafted with wt or IAb-deficient OT-II BM. Six weeks after reconstitution, thymocytes from the indicated mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4+CD8−Vα2+ cells, right). Contour plots (left) show a representative experiment for recipients of IAb−/− OT-II BM. Histograms (right) show the mean ± SEM for each group. n = number of mice pooled from several experiments. Figure 3B, Figure 5, and supplemental Figure 3 share the same groups lacking expression of the RIP transgene. Significance relative to WT: *P ≤ .05; ***P ≤ .001. In separate experiments, DCs from chimeric mice receiving IAb-deficient were shown to be virtually all derived from donor BM as evidenced by the absence of cells expressing high levels of MHC II and CD11c (data not shown).

RIP-mOVA mTEC show Aire-dependent regulation of mOVA and directly cause deletion of OT-II cells. (A) Aire regulates mOVA mRNA expression in RIP-mOVA transgenic mice. Relative expression of Aire, Ins2, Spna2, and OVA was determined by quantitative-real time PCR on cDNA prepared from CD45−-enriched thymic cells. Expression values are shown relative to WT after normalization to Hprt. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. A total of 6-10 individual thymi were pooled per experiment. Significance relative to WT: ***P ≤ .001; ns indicates not significant. (B) mTEC are able to present OVA on MHC II. Lethally irradiated 8-week-old B6 or RIP-mOVA mice were grafted with wt or IAb-deficient OT-II BM. Six weeks after reconstitution, thymocytes from the indicated mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4+CD8−Vα2+ cells, right). Contour plots (left) show a representative experiment for recipients of IAb−/− OT-II BM. Histograms (right) show the mean ± SEM for each group. n = number of mice pooled from several experiments. Figure 3B, Figure 5, and supplemental Figure 3 share the same groups lacking expression of the RIP transgene. Significance relative to WT: *P ≤ .05; ***P ≤ .001. In separate experiments, DCs from chimeric mice receiving IAb-deficient were shown to be virtually all derived from donor BM as evidenced by the absence of cells expressing high levels of MHC II and CD11c (data not shown).

BM-derived cells are not essential for deletion in RIP-mOVA mice

Evidence from Gallegos and Bevan31 that deletion of OT-II cells was mediated by BM-derived cells suggested that Aire-dependent deletion required transfer of antigen from the mTECs to DCs. This, in conjunction with the data of Anderson and colleagues17 indicating that mOVA expression was unaffected by Aire, yet deletion of OT-II cells was impaired, implied that Aire affected mOVA transfer from mTECs to DCs. However, our finding that the presence of Aire increased mOVA mRNA expression questioned this conclusion because lack of deletion in Aire-deficient mice could now simply be attributed to changes in mOVA expression. The following piece of data also questioned the validity of the aforementioned conclusions. Analysis of chimeric mice in whom BM-derived cells could not present OVA (because of IA-deficiency) revealed a component of OT-II thymic deletion in RIP-mOVA mice that was mediated directly by mTEC (Figure 3B), which calls into question the conclusion of Gallegos and Bevan31 that deletion was entirely dependent on BM-derived cells.

In this experiment, IA-deficient OT-II BM was injected into lethally irradiated B6 or RIP-mOVA mice and selection of SP OT-II cells examined after 6 weeks. This showed a reduction in SP OT-II cells in RIP-mOVA recipients, indicating that even when BM-derived cells could not present OVA, other cells, presumably mTECs, could present MHC II-restricted OVA determinants and cause deletion of OT-II cells. Although our data confirm the experimental groups reported by Gallegos and Bevan,31 these authors were unable to deduce an mTEC-induced component of deletion because their experiments did not include the third experimental group consisting of WT mice given IA−/− BM (column 3), which reveals that more OT-II cells are selected when the BM lacks MHC II (compare columns 1 and 3). Without knowledge of this group, it would seem like all deletion depended on MHC II expression by BM cells, as originally interpreted.31

At first glance, it may seem somewhat surprising that lack of MHC II molecules on BM-derived cells led to an increase in OT-II selection. Our interpretation is that there is a self-peptide that deletes the greatest avidity OT-II cells and that this self-peptide is most efficiently presented by DC. The absence of MHC II on DC therefore allows selection of these greatest avidity cells.

So far, our studies have agreed with earlier findings that OVA-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells could be deleted as a consequence of Aire expression in RIP-mOVA mice,17 but without additional evidence, the simplest explanation of these data was that Aire regulated mOVA expression in mTECs and this was sufficient to impair the extent of presentation by the mTECs themselves.

Aire regulates OT-II deletion in RIP-OVAhi mice

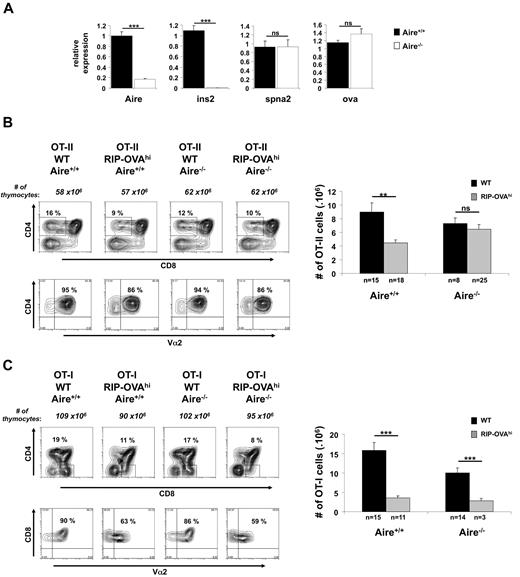

RIP-OVAhi mice are very similar to RIP-mOVA mice but express a secreted form of OVA in the β cells of the pancreas.22 Thus, in RIP-mOVA mice, mOVA is membrane bound, whereas in RIP-OVAhi mice, OVA is secreted. One critical difference between these 2 lines, however, is that, in contrast to RIP-mOVA mice, OVA mRNA expression by thymic CD45− cells in RIP-OVAhi mice was not regulated by Aire (Figure 4A). This line therefore provided us with the opportunity to examine whether Aire could affect negative selection by mechanisms other than regulation of autoantigen expression.

RIP-OVAhi mTEC show Aire-independent regulation of OVAhi and cause deletion of OT-I cells but not the OT-II cells. (A) Relative expression of Aire, Ins2, Spna2, and OVAhi was determined by quantitative RT-PCR on cDNA prepared from CD45−-enriched cells. Expression values are shown relative to WT after normalization to Hprt. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. A total of 6-8 individual thymi were pooled per experiment. Significance relative to WT: ***P ≤ .001; ns indicates not significant. (B) Thymocytes (3-week-old mice) generated by crossing OT-II.Aire+/− to RIP-OVAhi.Aire+/− mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4+CD8−Vα2+ cells, right). (C) Thymocytes (3-week-old mice) generated by crossing OT-I.Aire+/− to RIP-OVAhi.Aire+/− mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4−CD8+Vα2+ cells, right). Contour plots show a representative experiment. Histogram shows the mean ± SEM for each group. n = number of mice pooled from several experiments. Significance relative to WT: **P ≤ .01; ***P ≤ .001; ns indicates not significant.

RIP-OVAhi mTEC show Aire-independent regulation of OVAhi and cause deletion of OT-I cells but not the OT-II cells. (A) Relative expression of Aire, Ins2, Spna2, and OVAhi was determined by quantitative RT-PCR on cDNA prepared from CD45−-enriched cells. Expression values are shown relative to WT after normalization to Hprt. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. A total of 6-8 individual thymi were pooled per experiment. Significance relative to WT: ***P ≤ .001; ns indicates not significant. (B) Thymocytes (3-week-old mice) generated by crossing OT-II.Aire+/− to RIP-OVAhi.Aire+/− mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4+CD8−Vα2+ cells, right). (C) Thymocytes (3-week-old mice) generated by crossing OT-I.Aire+/− to RIP-OVAhi.Aire+/− mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4−CD8+Vα2+ cells, right). Contour plots show a representative experiment. Histogram shows the mean ± SEM for each group. n = number of mice pooled from several experiments. Significance relative to WT: **P ≤ .01; ***P ≤ .001; ns indicates not significant.

To examine thymic selection, RIP-OVAhi mice were crossed to OT-I or OT-II mice and then Aire deficiency introduced by further crossing (Figure 4B-C). RIP-OVAhi mice expressing Aire showed efficient thymic deletion of OT-II cells, and this was abolished by Aire-deficiency (Figure 4B). This Aire-dependent deletion extended to BM chimeras (Figure 5A), but in contrast to RIP-mOVA mice, mTEC from RIP-OVAhi mice did not directly contribute to antigen presentation for deletion of OT-II as chimeras with IA-deficient BM failed to delete OT-II cells (Figure 5B).

Aire expression in mTEC and BM-derived cells are required to cause the deletion of OT-II cells. (A) Thymocytes (6 weeks postreconstitution) from chimeric mice generated by reconstituting wt.Aire+/+, wt.Aire−/−, RIP-OVAhi.Aire+/+, or RIP-OVAhi.Aire−/− mice with OT-II BM were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4+CD8−Vα2+ cells, right). (B) mTECs are not able to present OVA on MHC II. Lethally irradiated 8-week-old B6 or RIP-OVAhi mice were grafted with IAb-deficient OT-II BM. At 6 weeks after reconstitution, thymocytes from the indicated mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4+CD8−Vα2+ cells, right). Contour plots show a representative experiment. Histogram shows the mean ± SEM for each group. n = number of mice pooled from several experiments. Figure 5A and supplemental Figure 3 as well as Figures 5B and 3B share, respectively, the same groups lacking expression of the RIP transgene. Significance relative to WT: ***P ≤ .001; ns indicates not significant.

Aire expression in mTEC and BM-derived cells are required to cause the deletion of OT-II cells. (A) Thymocytes (6 weeks postreconstitution) from chimeric mice generated by reconstituting wt.Aire+/+, wt.Aire−/−, RIP-OVAhi.Aire+/+, or RIP-OVAhi.Aire−/− mice with OT-II BM were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4+CD8−Vα2+ cells, right). (B) mTECs are not able to present OVA on MHC II. Lethally irradiated 8-week-old B6 or RIP-OVAhi mice were grafted with IAb-deficient OT-II BM. At 6 weeks after reconstitution, thymocytes from the indicated mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4+CD8−Vα2+ cells, right). Contour plots show a representative experiment. Histogram shows the mean ± SEM for each group. n = number of mice pooled from several experiments. Figure 5A and supplemental Figure 3 as well as Figures 5B and 3B share, respectively, the same groups lacking expression of the RIP transgene. Significance relative to WT: ***P ≤ .001; ns indicates not significant.

Unlike RIP-mOVA mice, we were able to obtain a small number of RIP-OVAhi × OT-I mice that were Aire deficient (Figure 4C). These mice showed similar deletion to that of their WT (Aire-sufficient) control mice, a finding that was confirmed with the use of chimeric mice (Figure 6). These data indicated that, in contrast to RIP-mOVA mice, Aire did not control deletion of CD8 T cells specific for MHC I-restricted OVA in RIP-OVAhi mice.

Aire is not involved in the deletion of OT-I cells. Thymocytes (6 weeks postreconstitution) from chimeric mice generated by reconstituting wt.Aire+/+, wt.Aire−/−, RIP-OVAhi.Aire+/+, or RIP-OVAhi.Aire−/− mice with OT-I BM were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4−CD8+Vα2+ cells, right). Representative contour plots were not all from the same experiment: Aire+/+ groups are matched, as are Aire−/− groups. Histograms show the mean ± SEM for each group. n = number of mice pooled from several experiments. Figures 6 and 2B share the same groups lacking expression of the RIP transgene. Significance relative to WT: **P ≤ .01; ***P ≤ .001; ns indicates not significant.

Aire is not involved in the deletion of OT-I cells. Thymocytes (6 weeks postreconstitution) from chimeric mice generated by reconstituting wt.Aire+/+, wt.Aire−/−, RIP-OVAhi.Aire+/+, or RIP-OVAhi.Aire−/− mice with OT-I BM were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and Vα2 (representative contour plots, left) and enumerated for SP thymocytes expressing high levels of TCR (CD4−CD8+Vα2+ cells, right). Representative contour plots were not all from the same experiment: Aire+/+ groups are matched, as are Aire−/− groups. Histograms show the mean ± SEM for each group. n = number of mice pooled from several experiments. Figures 6 and 2B share the same groups lacking expression of the RIP transgene. Significance relative to WT: **P ≤ .01; ***P ≤ .001; ns indicates not significant.

In summary, deletion of OT-I cells in RIP-OVAhi mice was not dependent on Aire expression, which paralleled a lack of regulation of OVA mRNA by Aire. In contrast, OT-II deletion was Aire dependent but was not directly mediated by mTEC antigen presentation, instead requiring BM-derived APC, presumably DC. A summary of our data can be found in supplemental Table 1 and the conclusions in Table 1.

Summary of thymic tolerance phenotype for OT-I and OT-II cells in RIP-mOVA and RIP-OVAhi transgenic mice

| Phenotype . | OT-I Deletion . | OT-II Deletion . | OVA expression . |

|---|---|---|---|

| RIP-mOVA | |||

| Aire dependent | Yes | Yes | Partial |

| DC dependent* | No | ||

| RIP-OVAhi | |||

| Aire dependent | No | Yes | No |

| DC dependent* | Yes |

| Phenotype . | OT-I Deletion . | OT-II Deletion . | OVA expression . |

|---|---|---|---|

| RIP-mOVA | |||

| Aire dependent | Yes | Yes | Partial |

| DC dependent* | No | ||

| RIP-OVAhi | |||

| Aire dependent | No | Yes | No |

| DC dependent* | Yes |

DC indicates dendritic cell; OVA, ovalbumin; and RIP-mOVA, rat insulin promoter membrane-bound form of ovalbumin.

For simplicity, we have indicated whether tolerance was DC dependent, but formally we have only proven that it is mediated by BM-derived cell.

Search for a mechanism to explain how Aire regulates thymic selection

The aforementioned studies implied that Aire expression in the mTECs of RIP-OVAhi mice somehow regulated a process required to allow efficient MHC II-restricted antigen presentation by thymic DCs. This might be mediated in several ways, including via control of DC maturation, because MHC II surface expression is up-regulated extensively on maturation.39 However, careful analysis of the maturation state of DCs in wild-type and Aire-deficient mice failed to identify any differences (supplemental Figure 5).

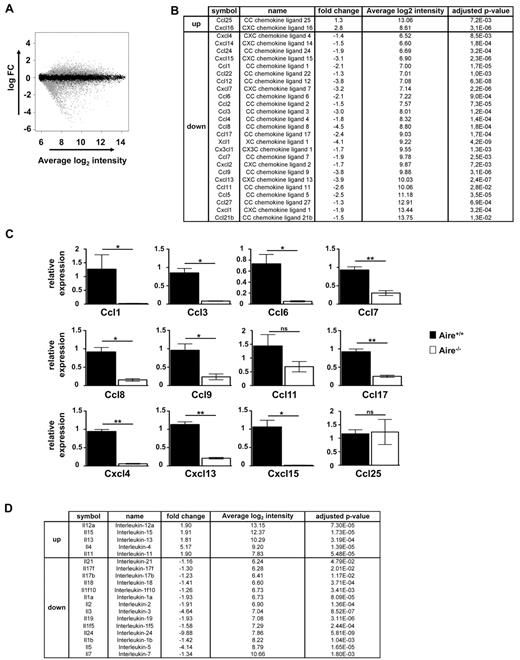

An alternative possibility was that Aire regulated expression of chemokines that might bring DCs and mTECs together. To examine this possibility, microarray analysis was conducted by the use of mRNA from WT and Aire-deficient mTEC (Figure 7). This showed a wealth of chemokines that were significantly affected by Aire (Figure 7B), many confirmed by real-time RT-PCR (Figure 7C). Although these data provide some insight into the potential complexity of thymic maturation, the redundancy of chemokine function together with the multiple points at which chemokines contribute to thymic development, suggest that to gain more specific understanding we will most likely require mTEC-specific chemokine gene deletion.

Aire regulates a plethora of cytokines and chemokines in mTECs. (A) The Fitted model MA plot representing different genes (4002 down and 4366 up) regulated by Aire (gray dots) according to the fold change and average intensity at a 5% FDR using Illumina beadchip. (B) List of chemokine genes whose expression levels differ significantly between Aire+/+ and Aire−/− mTEC according to the Illumina beadchip analysis presented with fold change, average of the intensity, and adjusted P value. (C) Relative expression of Ccl1, Ccl3, Ccl6, Ccl7, Ccl8, Ccl9, Ccl11, Ccl17, Cxcl4, Cxcl13, Cxcl15, and Ccl25 was determined by quantitative real-time PCR on cDNA prepared from thymic CD45−MHC IIhi Ly51− cells. Expression values are shown in relative to WT after normalization to Hprt. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. A total of 6-8 individual thymi were pooled per experiment. Significance relative to WT: *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01; ns indicates not significant. (D) List of cytokine genes whose expression levels differ significantly between Aire+/+ and Aire−/− mTEC according to the Illumina beadchip analysis presented with fold change, average of the intensity, and adjusted P value.

Aire regulates a plethora of cytokines and chemokines in mTECs. (A) The Fitted model MA plot representing different genes (4002 down and 4366 up) regulated by Aire (gray dots) according to the fold change and average intensity at a 5% FDR using Illumina beadchip. (B) List of chemokine genes whose expression levels differ significantly between Aire+/+ and Aire−/− mTEC according to the Illumina beadchip analysis presented with fold change, average of the intensity, and adjusted P value. (C) Relative expression of Ccl1, Ccl3, Ccl6, Ccl7, Ccl8, Ccl9, Ccl11, Ccl17, Cxcl4, Cxcl13, Cxcl15, and Ccl25 was determined by quantitative real-time PCR on cDNA prepared from thymic CD45−MHC IIhi Ly51− cells. Expression values are shown in relative to WT after normalization to Hprt. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. A total of 6-8 individual thymi were pooled per experiment. Significance relative to WT: *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01; ns indicates not significant. (D) List of cytokine genes whose expression levels differ significantly between Aire+/+ and Aire−/− mTEC according to the Illumina beadchip analysis presented with fold change, average of the intensity, and adjusted P value.

Because chemokines and cytokines have also been reported to play a role in positive selection,40,41 it is worth considering that any or several of these changes in chemokines (Figure 7B) or changes in cytokines (Figure 7D) detected for Aire-deficient mTECs may contribute to the defect seen for generation of SP cells (eg, Figure 1).

Discussion

The primary conclusion of this report is that Aire can mediate thymic deletion of CD4 T cells by a mechanism that is independent of the regulation of TSA expression and that relies on the indirect presentation of mTEC-derived TSAs by BM-derived cells. The simplest interpretation is that Aire facilitates transfer of antigen from mTECs to DCs.

A similar conclusion could have been reached by examining the combined data of 2 reports that used the RIP-mOVA model.17,31 However, our study now shows some problems with the data underlying these studies. Thus, although the conclusion may be correct, it was probably reached fortuitously. Anderson et al17 originally claim that Aire does not regulate mOVA expression in the RIP-mOVA thymus, yet our analysis showed a 30% reduction in mOVA expression in the absence of Aire. This level of reduction was recently also discovered by Anderson's group when they used a novel murine model expressing a dominant negative Aire mutation.32 Why the earlier study did not reveal Aire-regulated mOVA expression is unclear but may relate to difficulty in detecting the relatively small change or to their use of a mixed SV/129:B6 background.

Gallegos and Bevan31 provided evidence that OT-II cells were deleted as a consequence of recognition of antigen solely on BM-derived cells, whereas we showed that presentation by non-BM–derived cells was also able to mediate deletion. This discrepancy was simply because Gallegos and Bevan31 did not include what we originally considered to be a trivial control in which MHC II-deficient OT-II BM was introduced into wild-type mice. This control, however, turned out to be important because it revealed that there was increased SP OT-II cells42 in the absence of MHC II expression on BM-derived cells (compare IAb-sufficient and deficient OT-II BM into WT chimeras from Figure 3B, right, black bars). Thus, when the number of SP OT-II cells were compared in wild-type and RIP-mOVA chimeras receiving the same donor BM type, ie MHC II-deficient, a substantial degree of OT-II deletion by non-BM–derived cells was evident. In light of this observation and the noted 30% reduction in mOVA expression in the absence of Aire, the impaired negative selection of both OT-I and OT-II cells in Aire-deficient RIP-mOVA mice reported by Anderson et al17 and confirmed here, could simply be explained by a reduction in available mOVA for direct presentation by mTEC.

It is interesting that mTEC can directly delete OT-II in RIP-mOVA mice yet require DC for deletion in RIP-OVAhi mice. We speculate that mTECs are able to directly negatively selected OT-II cells when expressing the RIP-mOVA transgene because of the membrane-associated nature of mOVA, which may facilitate incorporation into the MHC II processing pathway of mTECs, perhaps by tethering it to the cell. In contrast, soluble secreted OVA may be poorly retained in mTECs and only efficiently captured by DCs.

In contrast to RIP-mOVA mice, RIP-OVAhi mice appear to fulfill the necessary requirements to reach the conclusion that Aire can regulate indirect presentation of mTEC-derived antigens, the conclusion potentially implicated by the earlier studies.17 These mice showed no evidence for Aire regulation of OVA expression in thymic epithelial cells, but deleted OT-II cells in an Aire-dependent manner that required presentation by a BM-derived cell. The Aire-dependence of OT-II deletion by soluble OVA contrasts that reported for human C-reactive protein (hCRP).17,43 hCRP transgenic mice express hCRP in mTEC in an Aire-independent manner and, in contrast to RIP-OVAhi mice, are able to delete specific CD4 T cells in the absence of Aire.17 The lack of Aire-dependence for such deletional tolerance was suggested to relate to the capacity of hCRP to be secreted and indirectly presented by APC. However, no evidence was provided for such indirect presentation and, thus, an alternative possibility is that hCRP is more efficiently presented by mTEC than OVA, and that such direct presentation is not impaired in Aire-deficient mice.

A second conclusion from our studies is that Aire expression can augment the number of SP thymocytes. This effect extends to several different TCR transgenic specificities, suggesting that it is unlikely to reflect changes in specific antigen expression, more likely implicating a general influence on thymocyte development or selection. In an earlier report,20 we observed a trend toward a decrease in SP thymocytes in Aire-deficient mice, although this did not reach significance. Li et al30 also found no apparent difference in SP thymocyte numbers in Aire-deficient mice but, of importance, did report a developmental block from SP3 to SP4, which may underlie our observation. The lack of any significant effect on the number of SP generated from a normal repertoire, yet an effect on transgenic T cells, is consistent with an effect on positive selection rather than survival or migration. Altered positive selection could create a shift of the affinity of those cells selected, which would be unlikely to alter the frequency of cells selected from a diverse (normal) repertoire but could affect the selection of a TCR transgenic.

It is unclear how Aire controls the indirect presentation of OVA by BM-derived cells, though several possibilities have been considered. Our analysis of DC maturation markers excluded possible contributions by Aire to this process because no obvious changes in the maturity of thymic DCs were evident in the absence of Aire. However, it has been suggested that access to mTEC-derived antigen may be compromised by reduced mTEC apoptosis.18 There is a modest increase in the number of mature mTEC in Aire-deficient mice, which may be a consequence of Aire-regulated control of apoptosis.18 Indirect presentation of mTEC-expressed antigens by thymic DCs could therefore be impaired if apoptotic mTECs are the primary source of antigen. Alternatively, Aire may regulate expression of chemokines important for attracting DC or T cells into the vicinity of the mTECs for acquisition or recognition of antigen, respectively. Interestingly, Koble and Kyewski44 describe a constitutive and unidirectional transfer route for self-antigens between mTEC and DC, which is possibly unique to the microenvironment of the thymic medulla.

Anderson et al17 used gene chip analysis of mTEC from wild-type or Aire-deficient mice to show that several chemokines were down- (CCL17, CCL22, and CXCL9) or up-regulated (CCL19, CXCL10, or CCL25) in the thymus of Aire-deficient mice. Laan et al45 also report a reduction of CCL17 and CCL22 and an increase in CCL25 in Aire deficient mice but show reduced levels of CCL5, CCL19, and CCL21. In the present study, we observed that Aire regulated the expression of at least 27 chemokines and 19 interleukins, many of which were validated by quantitative PCR, suggesting many possible candidates for altering cell migration.

Laan et al45 report changes to CCR4 and CCR7 ligands in Aire-deficient mice and provide evidence that these affect thymocyte migration. Many of the chemokines detected in our analysis have also been shown to bind chemokine receptors that regulate T-cell and/or DC migration,40,41,46 supporting this hypothesis. These include and CCL2, 7, 8, and 12, known to signal CCR2; CCL3, 4, and 5, known to signal CCR5; CCL21, known to signal CCR7; and CCL17, known to signal CCR4, which is down 2.4-fold in the absence of Aire and has been implicated in negative selection.47,48 This hypothesis is supported by additional evidence from microarray studies showing that DC from wild-type and Aire-deficient mice express the relevant chemokine receptors eg CCR2, 4, 5, and 7 (data not shown). Interestingly, although we did not observe an obvious redistribution of DC in Aire-deficient thymic medulla (data not shown), during review of this manuscript a subtle affect was reported, with greater confinement of DC to the corticomedullary junction.49 This effect was linked to Xcl1 regulation by Aire (which we had missed in our array analysis but verified on reexamination during review; Figure 7B), as a similar DC redistribution was seen in Xcl1-deficient mice.49

On the basis of previous evidence,17 it was assumed that Aire could regulate the transfer of antigen from mTEC to DC, with speculation that this occurred via the induction of mTEC apoptosis.18 In this report, we provide support for such a model, although we question some of the evidence leading to earlier speculation. The control of thymic negative selection is clearly critical for the safe development of an effective immune system. Aire provides a dominant contribution to the negative selection process primarily by regulating expression of a large array for TSAs, although clearly not all TSAs are regulated by Aire. Negative selection of T cells specific for these TSAs is most likely largely mediated via direct presentation by mTEC themselves, but clearly, some antigens can rely on DCs for efficient indirect presentation.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. Go, P. E. Crewther, M. Hancock, and J. Langley for technical assistance and the Australian Genome Research Facility.

This work was supported by the NHMRC and fellowships from La Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale (FRM) and the 6th FP of the EU, Marie Curie, contract 040998 (F.-X.H.); by Australian Postgraduate Awards (S.A.K.); NHMRC fellowships (171601, 461202, and 461204); NHMRC program grants (257501, 264573, 406700, and 454465); Eurothymaide and EURAPS; 6th FP of the EU; and the Nossal Leadership Award from WEHI (H.S.S.).

Authorship

Contribution: F.-X.H., S.A.K., G.MD, S.N.M., A.L., A.I.P., P.Z.F.C., and S.F. performed research and analyzed data; B.P. and G.K.S. analyzed gene expression arrays; C.C.G., L.W., and F.R.C. assisted in design experiments and reviewed the manuscript; and F.-X.H., H.S.S., and W.R.H. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

The current affiliation for F.-X.H. is Inserm Unité 643, CHU de Nantes, Institut de Transplantation et de Recherche en Transplantation-Urologie-Néphrologie, Université de Nantes, Nantes, France. The current affiliation for B.P. is Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: William R. Heath, Dept of Microbiology and Immunology, The University of Melbourne; Gate 11 Royal Parade, Parkville 3010, Victoria, Australia; e-mail: wrheath@unimelb.edu.au; or Hamish S. Scott, Dept of Molecular Pathology, SA Pathology and Centre for Cancer Biology, PO Box 14 Rundle Mall Post Office, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia; e-mail: hamish.scott@health.sa.gov.au.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal