The use of rituximab in the treatment of acquired autoimmune thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) has increased, becoming a standard of care for patients with relapsed TTP or patients who do not achieve a stable remission with plasma exchange therapy (PEX) plus steroids. In this issue of Blood, Scully et al report their findings that rituximab as an adjunct to PEX and steroids for initial therapy of acquired TTP significantly reduced the risk of relapse compared with historical controls.1 These findings suggest that rituximab may be beneficial when used as an adjunct to PEX in the initial therapy of acquired TTP.

Acquired TTP is often an autoimmune disorder, characterized by the development of an autoantibody against the ADAMTS13 protease, with a resulting deficiency of protease function. Severely deficient ADAMTS13 activity (< 10%) at presentation has been previously been associated with an increased risk for relapse compared with those with more than 10% ADAMTS13 activity (34% vs 4%, P < .001).2 It has been hypothesized that the early initiation of an effective immune modulating therapy targeting the antibody inhibitor of ADAMTS13 would reduce the PEX procedures to achieve remission, but could also decrease both early (exacerbation) and distant (relapse) recurrences of TTP. Scully et al demonstrate that the decreased relapse rate in the rituximab cohort correlated with suppression of the antibody inhibitor of ADAMTS13 and improvement in ADAMTS13 activity. While there was a small difference in the number of PEX to achieve remission between the rituximab cohort and historical controls, it was not statistically significant. Therapy with rituximab was well tolerated, with no excess infections or serious adverse events. Despite the limitations with using historical controls as the comparator arm, the large number of patients studied strengthens the conclusions of the study.

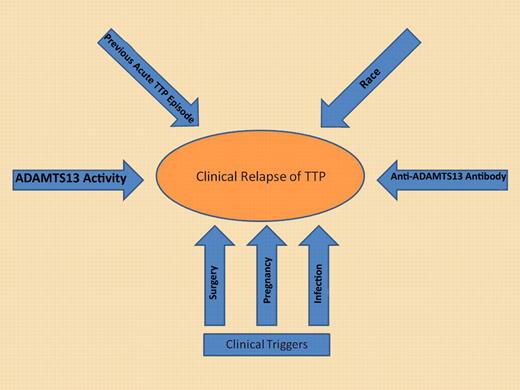

While severely deficient ADAMTS13 activity in remission may be a significant risk factor, additional potential risk factors must also be considered to determine the risk for relapse. It is likely the cumulative effect of all risk factors rather than the just ADAMTS13 activity alone that will accurately estimate the risk of relapse for an individual patient.

While severely deficient ADAMTS13 activity in remission may be a significant risk factor, additional potential risk factors must also be considered to determine the risk for relapse. It is likely the cumulative effect of all risk factors rather than the just ADAMTS13 activity alone that will accurately estimate the risk of relapse for an individual patient.

Increased attention has been focused on improving our ability to identify patients at greatest risk of relapse after achieving remission. In theory, this could identify patients who should be monitored closely, and in whom the risk of relapse may justify the potential risks of prophylactic therapy to prevent relapse. In this report from Scully et al, the rituximab-treated patients were followed for at least 12 months, but it is not clear if these patients should be considered cured, or rather could still be at risk for relapse. While one-half of relapses have been reported to occur in the first year of follow-up,2 the number of subjects who relapse would be expected increase with longer follow-up.3 There is mounting evidence that ADAMTS13 biomarkers measured in remission may identify those at greatest risk for relapse. Peyvandi et al measured ADAMTS13 activity and antibodies in 109 patients during remission, with samples obtained > 30 days from their last PEX.4 ADAMTS13 < 10% was found in 32% of patients in remission, and was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of relapse (odds ratio 2.9). Similarly, Jin et al measured the same ADAMTS13 biomarkers prospectively every 3 months in 24 patients (157 samples) during clinical remission, with an average follow-up of 23 months.5 Using logistic regression modeling, decreasing ADAMTS13 activity was associated with a greater risk of relapse in the following 3 months. Even more interesting was the marked variability in ADAMTS13 activity seen during follow-up that included the development of severely deficient ADAMTS13 activity (< 10%) in 5 of 19 subjects who did not experience a relapse, suggesting that an individual patient's risk of relapse may not be static during clinical remission. This same phenomenon was also reported previously by Kremer Hovinga et al.2 These data underscore the fact that although the risk of relapse with severely deficient ADAMTS13 activity may be increased, relapse is by no means uniform (see figure).4-6 The finding of severely deficient ADAMTS13 activity in a TTP patient in clinical remission should not be considered an absolute indication to initiate prophylactic immune suppressive therapy.

In this report by Scully et al, normalization of B-cell numbers occurred in 75% of subjects by 12 months. The regeneration of B cells was not associated with relapse of TTP or a significant increase in anti-ADAMTS13 IgG antibodies, but follow-up evaluations of anti-ADAMTS13 antibodies were not reported beyond 12 months. In the 4 relapses from the rituximab cohort, the median time to relapse was 27 months with all 4 patients having < 5% ADAMTS13 activity at relapse. Longer-term follow-up of all rituximab-treated subjects with serial monitoring of ADAMTS13 biomarkers will be required to ultimately determine whether there will be a recurrence of the anti-ADAMTS13 antibody and severely deficient ADAMTS13 activity.

It is also interesting to note in this report from Scully et al that nonwhites treated with rituximab required a greater number of PEX procedures to achieve remission. While TTP presents with increased frequency in African Americans compared with other races, these are among the first data to suggest there may be a biologic difference in nonwhites compared with whites in terms of response to therapy. The 6 subjects in this report who required more than 4 weekly rituximab treatments because of abnormal ADAMTS13 activity or persistently detectable anti-ADAMTS13 antibodies were all nonwhites, suggesting that acquired TTP in nonwhites may be more resistant or require more intense therapy. This would also be consistent with a previous report in which African American race was associated with an increased risk for exacerbation, or recurrence in the first 30 days after the last PEX procedure.7 Taken together these data support the hypothesis that nonwhite/African American race may be associated with a disease biology that may be more resistant to treatment and more susceptible to relapse.

This report by Scully et al is a significant step forward in the treatment of acquired TTP, but even more importantly these data add to our understanding of the factors important for both achieving a sustained remission and relapse of TTP. The recognition that the decrease in relapse rates in the rituximab-treated cohort correlate with suppression of anti-ADAMTS13 antibodies, and the differential response to rituximab in nonwhites put together additional pieces to the puzzle of the factors involved in remission and relapse of TTP.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■