In this issue of Blood, Meiler and colleagues report that Pomalidamide, an immunomodulatory drug, stimulates fetal hemoglobin (HbF) production in transgenic sickle mice to a degree similar to that of hydroxyurea, without cytotoxicity and with expanded marrow erythropoiesis, producing 2 therapeutic benefits that address the pathology of sickle cell disease: polymerization of sickle hemoglobin and hemolytic anemia.1 This is a highly encouraging development for a serious disease with only one approved therapeutic.

Sickle cell disease afflicts 80 000-100 000 Americans and is considered a global health burden.2 The pathophysiology of sickle cell disease is initiated by polymerization of deoxy sickle hemoglobin, which results in sickling of red blood cells and hemolytic anemia, reducing the red cell lifespan to an average of 16 days.2,3 The deformed red cells adhere to endothelium and cause a cascade of secondary pathology, including adhesion of other cell types, vaso-occlusion, inflammation, vascular remodeling, and widespread organ damage.3,4 Anemia contributes to cardiomegaly and exercise intolerance.

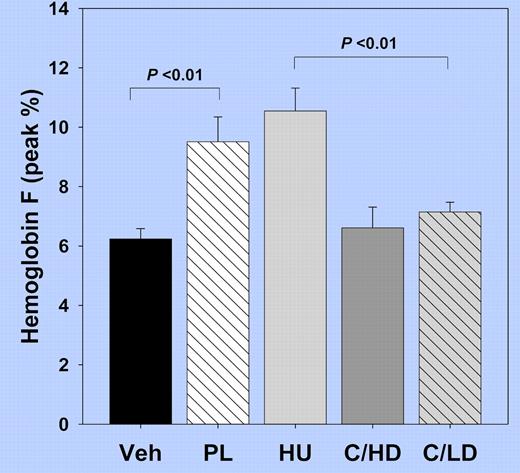

Hbf levels in sickle transgenic mice after 8 weeks of treatment with Vehicle (Veh), Pomalidomide (PL), Hydroxyurea (HU), and in combination with HU at high dose (C/HD) or low dose (C/LD).

Hbf levels in sickle transgenic mice after 8 weeks of treatment with Vehicle (Veh), Pomalidomide (PL), Hydroxyurea (HU), and in combination with HU at high dose (C/HD) or low dose (C/LD).

Decades of work have clearly established that fetal hemoglobin (HbF) and F-cell proportions are the major modifiers and determinants of severity in sickle cell disease (reviewed in Akinsheye et al,2 Perrine,3 and Bunn et al4 ). HbF and tetramers of αβSγ inhibit the polymerization process, and HbF levels > 20% prevent most sickle cell disease clinical events.2-4 Examples of this ameliorating effect include infants with HbSS, who are well until after completion of the fetal to sickle globin gene switch, patients with S-HPFH (who have 70% HbS and 30% HbF), or patients with the Saudi-Indian haplotype (HbF levels > 20%), who are asymptomatic or have only mild disease.2-5 The Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease documented that even incremental increases in HbF reduce clinical events.6

In this report, Pomalidamide treatment of sickle transgenic mice increases HbF to levels equal to those induced by treatment with hydroxyurea (HU; see figure), and comparable to the average response observed in patients on the Multi-Center Study of Hydroxyurea.7 There is reason to anticipate higher HbF induction by Pomalidamide in humans than in mice, because mice normally switch from embryonic to adult globin without a developmental window of fetal globin gene expression. In contrast to the cytotoxicity observed in all hematopoietic lineages in the HU-treated mice, Pomalidamide treatment resulted in a doubling of erythroid cells in the marrow. Total Hb increased by 0.5 g/dL above controls and by 1.5 g/dL above levels in HU-treated mice. These 2 beneficial effects comprise a holy grail for treatment modalities to reduce the primary pathology in sickle cell anemia, a disease for which only 1 drug has ever been approved, more than 15 years ago. Anti-inflammatory effects of Pomalidamide may add a third component. Although there was no additive activity observed with simultaneous administration of HU and Pomalidamide, sequential dosing of the 2 agents might produce higher activity, as intermittent dosing regimens have increased activity of other drugs, such as Butyrate.3

At least half of adult patients in most practices are considered responsive to HU, the only approved therapeutic available, and higher responses occur in children.2,3,8 This is a significant degree of benefit for any drug, as differences in drug metabolism alone render most therapeutics effective in only 25%-60% of patients.9 A recent 17.5-year follow-up study has shown there is still high mortality in sickle cell patients (43%), and prolonged HU therapy (at least 5 years) is needed for a survival benefit.10 Costs of supportive therapy for sickle cell disease are still high: analgesia, hospitalizations, transfusions, chelation, orthopedic surgeries, and diagnostic studies consume billions of health care dollars annually, and these costs do not include the disabilities and compromised lives caused by the disease. Some patients who still suffer some vaso-occlusive crises despite taking HU are wary of long-term use of a drug with a black-box warning regarding carcinogenicity. New HbF-inducing agents, particularly those with distinct mechanisms of action such as Pomalidomide, could make a great impact on the treatment of sickle cell disease as single agents or in a combination chemotherapy approach.11

Trials of therapeutics for sickle cell disease have been challenging, at least partially due to the use of unrealistic end points. No single drug can effectively reduce all disease manifestations in a condition as pathophysiologically complex as sickle cell disease. Furthermore, the phenotypic heterogeneity of this global disease, affected by genetic modifiers only now being elucidated, make study populations diverse (reviewed in Akinsheye et al2 ). Trial end points that are meaningful (such as total Hb and HbF) and achievable within a reasonable time duration, and in patient numbers feasible to enroll for an orphan disease that is frequently confounded by serious clinical events, should be accepted for drug approval. Trial end points that are more relevant to the molecular actions or target of the drug should be considered. For example, drugs that are not designed to affect hemoglobin polymerization and consequent sickling (such as IGA17403 [Senicapoc] or Flocar) should not be held to an end point of reduction in secondary events such as pain crises for approval, when other meaningful, targeted end points were met. Indeed, drugs targeting aspects of sickle disease other than pain crises could be highly beneficial additions to our limited therapeutic repertoire. Surrogate biochemical markers have been accepted by the FDA for other diseases for many years (eg, cholesterol lowering for atherosclerosis), and elevations in HbF should be considered an acceptable surrogate end point for certain sickle cell therapeutic candidates.

Pomalidamide joins a short, sorely needed pipeline of new sickle cell therapeutic candidates, which target HbF, HbS, inflammatory or adhesion molecules. As patients continue to suffer the pain and ravages of this complex condition, approval of new therapeutics cannot come soon enough.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal