Abstract

Transplantation with 2-5 × 106 mobilized CD34+cells/kg body weight lowers transplantation costs and mortality. Mobilization is most commonly performed with recombinant human G-CSF with or without chemotherapy, but a proportion of patients/donors fail to mobilize sufficient cells. BM disease, prior treatment, and age are factors influencing mobilization, but genetics also contributes. Mobilization may fail because of the changes affecting the HSC/progenitor cell/BM niche integrity and chemotaxis. Poor mobilization affects patient outcome and increases resource use. Until recently increasing G-CSF dose and adding SCF have been used in poor mobilizers with limited success. However, plerixafor through its rapid direct blockage of the CXCR4/CXCL12 chemotaxis pathway and synergy with G-CSF and chemotherapy has become a new and important agent for mobilization. Its efficacy in upfront and failed mobilizers is well established. To maximize HSC harvest in poor mobilizers the clinician needs to optimize current mobilization protocols and to integrate novel agents such as plerixafor. These include when to mobilize in relation to chemotherapy, how to schedule and perform apheresis, how to identify poor mobilizers, and what are the criteria for preemptive and immediate salvage use of plerixafor.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has revolutionized the curative approach to a number of malignancies and BM failure syndromes by providing hematopoietic and immune rescue after high-dose cytoreductive therapy and, in allogeneic transplantations, graft-versus-tumor effect.1-4

The term “mobilization” was first used to describe a 4-fold increase of circulating myeloid progenitors (granulocyte macrophage CFU [CFU-GM]) after the administration of endotoxin to healthy volunteers in 1977.5 High levels of CFU-GM after recovery from myelosuppressive chemotherapy in humans was first described in 1976.6 However, it was not until the 1980s that the use of chemotherapy-mobilized HSCs for transplantation was established.7-9 Subsequently, a single high-dose cyclophosphamide was developed as a generic mobilizer.10

Prof Metcalf led the study that showed the potential of G-CSF in mobilization.11 Subsequently, 2 Australian centers in Melbourne and Adelaide showed for the first time the use of G-CSF–mobilized HSCs for transplantation,12 and reports of combined G-CSF and chemotherapy mobilization soon followed.13 Now, virtually all autologous and three-quarters of allogeneic transplantations are performed with mobilized HSCs (CIBMTR reports).14,15

The cell dose effect of HSCT describes a threshold of HSCs that, when transplanted, is associated with rapid and sustained blood count recovery.16 The benefits of rapid recovery are reduced hospitalization, blood product usage, and infections.12,17 The minimum threshold for autologous transplantation is currently defined as 2 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg body weight (BW).18 Many centers use a minimum of 3 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg BW for myeloablative and nonmyeloablative allogeneic and matched unrelated transplantations. Furthermore, > 5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg BW is associated with even lower resource use and faster and more complete platelet engraftment19 and better survival in allogeneic transplantations,20 and it is probable that higher cell doses (eg, ≥ 5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg BW) may be similarly beneficial in mismatched transplantations. In haplotype mismatched transplantations doses of ≥ 10 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg BW are often used.21 With the extension of transplantation to selected elderly patients,22 the improved safety is vital.

G-CSF–based mobilization regimens have a 5%-30% failure rate among healthy donors and patients, but ≤ 60% in high-risk patients such as those exposed to fludarabine.23-25 A conservative estimate of the number of patients who failed mobilization annually on the basis of the number of transplantations globally and the rate of failed mobilization is 5000-10 000 each year. Poor mobilization has significant consequences for the patient with potential loss of the transplant as a treatment option. Repeated attempts at mobilization increase resource use, morbidity, and patient/donor inconvenience. There is thus much interest in the prevention and salvage of mobilization failure with novel strategies.

Understanding the mechanism of mobilization is fundamental to develop novel strategies. The first reports of mobilization of HSCs in humans were empirical observations, and the hypothesis, untested, was that mobilization was a result of HSC proliferation. Mechanistic understanding of mobilization emerged when animal studies started.26 A number of pathways have been described, so it is timely to evaluate the risk factors for failed mobilization and how optimized protocols involving conventional and new agents could be developed.

This article will not cover the mobilization of other cells such as endothelial and mesenchymal progenitors, dendritic, or other immune or malignant cells.

Current mobilization regimens

G-CSF–based mobilization protocols

G-CSF with or without myelosuppressive chemotherapy has been the most commonly used mobilization protocols since the 1990s.12,13 When used alone, in both autologous12 and allogeneic transplantations,27 G-CSF is given at 10 μg/kg per day subcutaneously with apheresis beginning on the fifth day until the yield target is reached. There is no compelling evidence that twice daily administrations give a higher yield than a once-daily schedule.28

Combining G-CSF with chemotherapy achieves the twin aims of mobilization and antitumor activity and has been shown to result in a higher CD34+ cell yield than G-CSF alone.29 Regimens such as cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone/dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin or cyclophosphamide 1-5 g/m2 have been used with G-CSF that starts 1-3 days after cyclophosphamide. Apheresis is usually started when leukocyte count reaches > 2 × 109/L. The benefit of higher mobilization yield with higher doses of chemotherapy needs to be balanced against more red cell and platelet transfusions, and, frequently, hospitalization for febrile neutropenia,30 and it is more justified when significant antitumor effects exist.

A prospective study that compared 5 versus 10 μg/kg per day after standard chemotherapy was inconclusive.31 G-CSF 5 μg/kg per day is used in most units for combined G-CSF/chemotherapy mobilization.

The pegylated form of G-CSF (pegfilgrastim) showed similar kinetics of mobilization as filgrastim.32 A phase 1/2 study in healthy donors reported suboptimal mobilization with a dose of 6 mg but satisfactory yield with 12 mg.33 Such dose dependence was not seen when pegfilgrastim was used with cyclophosphamide.34

Lenograstim is a glycosylated form of G-CSF, whereas filgrastim is nonglycosylated. Several prospective studies have shown higher mobilization yield with lenograstim.35,36 Posthoc analysis indicated that this was because of better mobilization with lenograstim in males.36 In contrast to healthy donors, CD34+ cell yield appears similar in patients receiving either lenograstim or filgrastim after chemotherapy.37 The efficacy of biosimilar G-CSF is still to be confirmed.

SCF (ancestim) exists as a soluble form as well as a surface molecule on BM stromal cells. It binds to c-kit on HSCs and modulates proliferation and adhesion. As a single agent SCF has limited efficacy in HSC mobilization; however, synergy between SCF and G-CSF has been noted in animal models38 and in human subjects.39 SCF at 20 μg/kg subcutaneously was started 4 days before the start of G-CSF and continued with the G-CSF until the end of apheresis. Antihistamine and anti–5-hydroxytryptamine blocking agents should be administered concurrently to reduce the risks of anaphylactic reactions. In failed mobilizers SCF plus G-CSF with or without chemotherapy enabled adequate mobilization in ∼ 50% of patients.40 In prior fludarabine-exposed patients SCF with high-dose G-CSF resulted in a 63% success rate, almost doubling that in historical controls that used G-CSF alone.23 It is not available in many countries, including the United States.

Sargramostim, GM-CSF, is not more effective than G-CSF alone, has no synergy with G-CSF, and is limited by dose-related toxicities.41 Now, GM-CSF is rarely used.

Plerixafor

Plerixafor,42 a CXCR4 antagonist, reduces the binding and chemotaxis of HSCs to the BM stroma. It is used at 240 μg/m2 subcutaneously the evening before the scheduled apheresis because it generates peak CD34+ levels 6-9 hours after administration.43-45 It synergizes with G-CSF and chemotherapy. Plerixafor is the latest addition to the list of mobilizing agents and the first driven by understanding how mobilization occurs.

How HSC mobilization occurs

HSC niche and microvascular recirculation

The HSC niche.

HSCs reside within specific BM niches, anchored by adhesive interactions, and supported by stromal niche cells that provide ligands for adhesion as well as signals for HSC functions such as quiescence, proliferation, and self-renewal. Two anatomical HSC niches have been described in mouse BM: a vascular niche in which HSCs are in contact with perivascular mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and sinusoidal endothelial cells,46,47 and an endosteal niche in which HSCs are located within 2 cell diameters from osteoblasts covering endosteal bone surfaces48-50 and MSCs. An emerging model is that active HSCs that proliferate to renew the hematopoietic system are preferentially located in perivascular niches, whereas dormant HSCs that maintain a reserve are preferentially located in poorly perfused, hypoxic endosteal niches.51-53

The “players” in the HSC niche

The physical niche:

Perivascular pluripotent MSC and their osteogenic progenies form the physical niche in which the HSC resides.54

The adhesive and chemotactic interactions:

Perivascular MSCs, sinusoidal endothelial cells, and osteoprogenitors express adhesion molecules such as (1) VCAM-1/CD106 that binds its receptor integrin α4β1 expressed by HSCs, and (2) transmembrane SCF (kit ligand) that binds its receptor c-Kit (CD117) on HSCs. Another essential interaction is the chemotactic factor stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1/CXCL12) secreted by niche cells and its receptor CXCR4 on HSCs. Inducible deletion of any of these genes,55,56 or blockade of the relevant proteins with antagonists,44,57 induces HSC mobilization in the mouse.

Cells supporting the niche cells:

A population of CD68+ CD169+ phagocytic macrophages are adjacent to MSCs and osteoblasts that form the HSC niche. These macrophages are necessary for niche cells to express hematopoietic cytokines and CXCL1258,59 and are critical for the functional integrity of niches. Ablation of these macrophages disrupts niche function, resulting in a dramatic down-regulation of VCAM-1, SDF-1, and SCF expression and concomitant HSC mobilization58,59 (Figure 1).

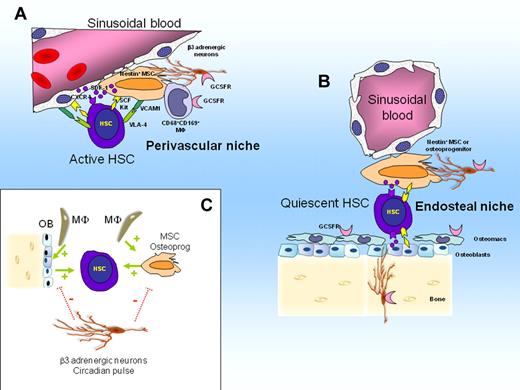

Model of HSC niche regulation in steady state. (A) Perivascular niches harboring active HSCs that regenerate the hematopoietic system. Active HSCs are in contact with perivascular nestin+ MSCs and sinusoidal endothelial cells. Both MSCs and sinusoidal endothelial cells express SDF-1, transmembrane SCF, and VCAM-1 that retain HSCs within the niche via adhesive and chemotactic interactions. (B) Endosteal niches harboring quiescent HSCs. Quiescent HSCs are in contact with nestin+ MSCs or osteoprogenitors or both. (C) Interactions between niches cells, HSCs, and adrenergic neurons. CD68+ CD169+ macrophages and osteomacs forming support function of nestin+ MSCs, osteoprogenitors and osteoblasts which in turn maintain HSCs in steady state (stimulating feed-back illustrated by green arrow). Sympathetic β3 adrenergic nerves inhibit SDF-1 secretion by MSCs and osteoblasts after a circadian pulse (negative pulse illustrated by dotted red bars).

Model of HSC niche regulation in steady state. (A) Perivascular niches harboring active HSCs that regenerate the hematopoietic system. Active HSCs are in contact with perivascular nestin+ MSCs and sinusoidal endothelial cells. Both MSCs and sinusoidal endothelial cells express SDF-1, transmembrane SCF, and VCAM-1 that retain HSCs within the niche via adhesive and chemotactic interactions. (B) Endosteal niches harboring quiescent HSCs. Quiescent HSCs are in contact with nestin+ MSCs or osteoprogenitors or both. (C) Interactions between niches cells, HSCs, and adrenergic neurons. CD68+ CD169+ macrophages and osteomacs forming support function of nestin+ MSCs, osteoprogenitors and osteoblasts which in turn maintain HSCs in steady state (stimulating feed-back illustrated by green arrow). Sympathetic β3 adrenergic nerves inhibit SDF-1 secretion by MSCs and osteoblasts after a circadian pulse (negative pulse illustrated by dotted red bars).

Mechanisms of mobilization

Mobilization is the iatrogenic augmentation of HSC recirculation that occurs at low levels in steady state. Murine experiments within the past decade have identified several pathways that lead to HSC mobilization.

G-CSF

The role of proteases:

Chemotherapy and G-CSF produce alterations in the composition of the HSC niches, including a marked down-regulation of adhesion and chemokine processes such as VCAM-1, SDF-1, and SCF.58,60,61 Initial investigations suggested that granulocytes and their progenitors release large amounts of proteases such as neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in the mobilized BM, which in concert with other proteases such as CD26 (expressed at the surface of HSCs62 ) complement cascade proteins C3 and C563,64 and the plasmin activation cascade,65 cleave and inactivate VCAM-1, SDF-1, CXCR4, c-Kit, and SCF. Indeed, mice rendered neutropenic by antibody treatment or deletion of the G-CSF receptor (Csf3r) gene mobilize poorly in response to G-CSF or cyclophosphamide.66,67 However, the physiologic significance of proteases remains uncertain because mice lacking genes encoding some of these proteases will still mobilize normally in response to G-CSF.68

The role of BM macrophages:

The importance of CD68+ CD169+ BM macrophages in G-CSF mobilization was discovered recently.58,59,69 G-CSF administration causes the loss of these macrophages, resulting in down-regulation of SDF-1, SCF, and VCAM-1 expression by niche cells.58,59,69 It was therefore concluded that the loss of these niche-supportive macrophages results in inhibition of bone formation and HSC-supportive niche function and contributes to G-CSF–induced mobilization.58,59,69

The role of complement, the thrombolytic pathway, and chemotactic gradients of SDF-1 and sphingosine-1-phosphate:

G-CSF administration activates the complement cascade63,64 and thrombolytic pathway,65 both shown to play a role in the mobilizing response to G-CSF. Complement activation also causes the release of erythrocytes sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) into the plasma. S1P is a lipid that is highly chemoattractant to HSCs. S1P accumulates in plasma of mobilized mice, forming a counter gradient that chemoattracts HSCs into the circulation.70 Therefore, mobilization could result from the simultaneous weakening of the SDF-1 gradient released by niche cells, weakening of adhesive interactions mediated by VCAM-1 and transmembrane SCF, together with the formation of a counter gradient of S1P caused by complement activation.

The role of β-adrenergic sympathetic nerves:

In mice and humans the steady state recirculation of HSCs follows a circadian rhythm under the control of sympathetic adrenergic nerves that promote rhythmic oscillations in the production of SDF-1 by HSC niche cells and CXCR4 expression by HSCs themselves.71,72 Consequently in mice, SDF-1 expression in the BM and CXCR4 expression on HSCs is lowest 5 hours after the onset of light when HSCs in the peripheral circulation peak. In mice mobilized with G-CSF or plerixafor, more HSCs were harvested at this circadian peak.70 In a retrospective study comprising 85 healthy mobilized donors, this peak was in the afternoon with 85% higher CD34+ yields than in the morning.72 The β2 agonist clenbuterol also increases mobilization in mice.73 Therefore, time of collection and β2 agonists could be 2 simple strategies to further increase mobilization yields.

Hence, it is increasingly apparent that the mobilization response to G-CSF involves both macrophage-mediated and adrenergic sympathetic pathways (Figure 2). Targeting these 2 pathways to improve mobilization efficiency is an interesting avenue to explore.

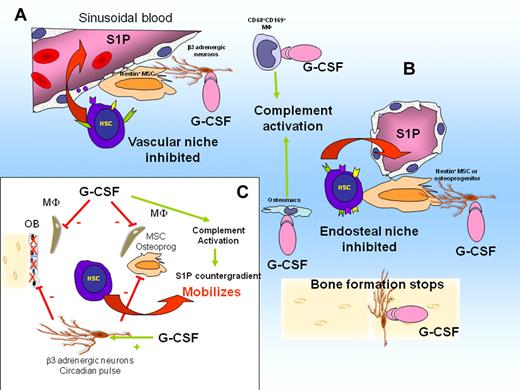

G-CSF deregulates niches and causes HSC mobilization. (A) G-CSF activates CD68+ CD169+ macrophages in perivascular niches. This suppresses macrophage supportive function for MSCs. Consequently, expression of CXCL12, SCF, and VCAM-1 is down-regulated. Complement cascade is activated, leading to erythrocyte lysis and release of S1P in the blood, creating a chemotactic counter gradient. Active HSCs are mobilized. (B) G-CSF suppresses osteomacs in endosteal niches. Osteoblasts are lost, bone formation stops, and expression of CXCL12, SCF, and VCAM-1 by MSCs and osteoprogenitors is down-regulated. Dormant HSCs are mobilized. (C) Schematic representation of interactions in response to G-CSF. β-adrenergic neuron activation by G-CSF inhibits SDF-1 production by MSCs, osteoprogenitors, and osteoblasts and inhibits bone formation by osteoblasts (solid red bars). Stimulation of osteomacs and CD169+ macrophages by G-CSF (solid red bars) suppresses their supportive function for MSCs and osteoblasts. Consequently, expression of SDF-1, Kit ligand, and VCAM-1 by osteoprogenitors and MSCs is down-regulated. Complement cascade is activated by G-CSF, resulting in S1P release into the blood.

G-CSF deregulates niches and causes HSC mobilization. (A) G-CSF activates CD68+ CD169+ macrophages in perivascular niches. This suppresses macrophage supportive function for MSCs. Consequently, expression of CXCL12, SCF, and VCAM-1 is down-regulated. Complement cascade is activated, leading to erythrocyte lysis and release of S1P in the blood, creating a chemotactic counter gradient. Active HSCs are mobilized. (B) G-CSF suppresses osteomacs in endosteal niches. Osteoblasts are lost, bone formation stops, and expression of CXCL12, SCF, and VCAM-1 by MSCs and osteoprogenitors is down-regulated. Dormant HSCs are mobilized. (C) Schematic representation of interactions in response to G-CSF. β-adrenergic neuron activation by G-CSF inhibits SDF-1 production by MSCs, osteoprogenitors, and osteoblasts and inhibits bone formation by osteoblasts (solid red bars). Stimulation of osteomacs and CD169+ macrophages by G-CSF (solid red bars) suppresses their supportive function for MSCs and osteoblasts. Consequently, expression of SDF-1, Kit ligand, and VCAM-1 by osteoprogenitors and MSCs is down-regulated. Complement cascade is activated by G-CSF, resulting in S1P release into the blood.

Cyclophosphamide.

HSC mobilization occurs during the recovery phase after cyclophosphamide. A marked reduction of osteoblasts, osteoblast-supportive endosteal macrophages (osteomacs), and CXCL12 expression results in the disruption of the CXCL12 gradient (Winkler IG, Petit AR, Raggatt LI, Bendall LJ, Jacobsen R, Barbier V, Nowlan B, Cisterre A, Shen Y, Sims NA, Levesque JP, manuscript in preparation). Unlike G-CSF, however, cyclophosphamide does not down-regulate the expression of KIT ligand, enabling rapid recruitment of HSCs into proliferation to restore BM cellularity (Winkler IG, Petit AR, Raggatt LI, Bendall LJ, Jacobsen R, Barbier V, Nowlan B, Cisterre A, Shen Y, Sims NA, Levesque JP, manuscript in preparation). The synergism with G-CSF may result from a more complete down-regulation of CXCL12 combined with enhanced number of BM HSCs because of the induction of HSC self-renewal in response to chemotherapy.

CXCR4 antagonists.

Because the chemotactic interaction between SDF-1 and its receptor CXCR4 is critical to HSC retention within the BM, CXCR4 blockade with antagonists or administration of stable analogs of SDF-1 effectively mobilizes HSCs. Plerixafor is the only CXCR4 antagonist currently available. Alone, plerixafor rapidly mobilizes HSCs, peaking at 6-9 hours.43-45 Plerixafor directly binds to CXCR4 and inhibits chemotactic signaling in cells.74,75 Plerixafor also promotes the release of SDF-1 from CXCR4+ osteoblastic and endothelial cells into the circulation.76 It therefore seems to counter the chemotactic SDF-1 gradient between the BM stroma and the circulation, favoring the egress of HSCs from the BM. Of note, the down-regulation of SDF-1 in response to G-CSF is always partial and at best 80%.58,73,77,78 Unlike G-CSF, plerixafor bypasses the macrophage pathway and does not promote the loss of endosteal osteomacs and osteoblasts (Winkler IG, Petit AR, Raggatt LI, Bendall LJ, Jacobsen R, Barbier V, Nowlan B, Cisterre A, Shen Y, Sims NA, Levesque JP, manuscript in preparation). Because of their different and complementary mechanisms of action, plerixafor shows marked synergism with G-CSF.44,45 Although plerixafor represents a landmark development in improving HSC mobilization strategies, it is important to note that 30% of patients failing G-CSF containing mobilization protocols still fail to mobilize adequately to this combination.

α4 Integrin (CD49d) antibodies.

Integrin α4β1 mediates HSC adhesion to VCAM-1, a key adhesive interaction for HSC retention within the BM stroma.79 A single dose of natalizumab (300 mg), a humanized function-blocking anti-CD49d antibody prescribed to patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis, was found to increase circulating CD34+ cells 5-fold 1 day after antibody infusion.80 In mice, a single dose of the small α4β1 integrin inhibitor BIO5192 mobilizes HSC/progenitor cell at 6 hours after a single dose and is additive to the effect of plerixafor.81 Therefore, α4β1 blockers may be of interest in patients who fail to mobilize adequately in response to G-CSF and plerixafor.

Poor mobilization: clinical risk factors and mechanistic understanding

Clinical risk factors for poor mobilization with conventional regimens have been well described (Table 1). Poor mobilization may be innate and inherent to a particular genetic combination specific to a person or acquired as a consequence of aging, prior treatments, or disease. The possible defects could be at one or more of three levels: (1) insufficient number of HSCs because of HSC intrinsic factors, (2) insufficient HSC number because of low number or defective niches, or (3) inadequate number or response of effector/supporter cells such as BM macrophages or β-adrenergic nerves. These possible defects are not mutually exclusive, but the therapeutic approach to correct them may be specific to each one.

Risk factors, mechanisms, and strategies to optimize collection in predicted poor mobilizer patients

| Risk factor . | Postulated mechanism . | Mobilization strategy . |

|---|---|---|

| Low steady-state platelet counts and PB CD34+ level | Reflects overall HSC reserve | Regimen promoting HSC proliferation, eg, SCF, cyclophosphamide |

| Low steady-state TNF-α level | May reflect niche dysfunction, including the macrophage response to G-CSF | Regimen bypassing the macrophage-dependent pathways, eg, plerixafor-containing regimen |

| Increasing age | Reduced HSC reserve because of the following:

| Regimen promoting HSC proliferation, eg, SCF, cyclophosphamide Add risk-adapted plerixafor to augment niche response to G-CSF Bisphosphonate treatment continued throughout collection PTH of interest in experimental models |

| Underlying disease | Paraneoplastic niche dysfunction Loss of niche to mass effect of tumor | Aim to clear BM of disease before collection |

| Prior extensive radiotherapy (RT) to red marrow | Direct HSC toxicity Toxicity to HSC niche | Rainy day collection before extensive RT when possible Risk-adapted plerixafor Regimen promoting HSC proliferation, eg, SCF, cyclophosphamide |

| Prior chemotherapy | ||

| Melphalan | Direct HSC toxicity | Avoid melphalan until autologous cells collected |

| Fludarabine | Direct HSC toxicity, niche damage | Collect HSCs early, after < 4 cycles of fludarabine |

| Intensive chemotherapy (eg, hyper-CVAD) | Dose-dense cycles may cause niche damage, and HSCs forced into cell cycle may not engraft as well | Use SCF or preemptive risk-adapted plerixafor for fludarabine-exposed and heavily pretreated patients |

| Prior lenalidomide | Possible effects on HSC motility Possible dysregulated HSC niche because of antiangiogenic effects | Collect HSC early, after < 4 cycles of treatment Temporarily withhold lenalidomide during collection. |

| Risk factor . | Postulated mechanism . | Mobilization strategy . |

|---|---|---|

| Low steady-state platelet counts and PB CD34+ level | Reflects overall HSC reserve | Regimen promoting HSC proliferation, eg, SCF, cyclophosphamide |

| Low steady-state TNF-α level | May reflect niche dysfunction, including the macrophage response to G-CSF | Regimen bypassing the macrophage-dependent pathways, eg, plerixafor-containing regimen |

| Increasing age | Reduced HSC reserve because of the following:

| Regimen promoting HSC proliferation, eg, SCF, cyclophosphamide Add risk-adapted plerixafor to augment niche response to G-CSF Bisphosphonate treatment continued throughout collection PTH of interest in experimental models |

| Underlying disease | Paraneoplastic niche dysfunction Loss of niche to mass effect of tumor | Aim to clear BM of disease before collection |

| Prior extensive radiotherapy (RT) to red marrow | Direct HSC toxicity Toxicity to HSC niche | Rainy day collection before extensive RT when possible Risk-adapted plerixafor Regimen promoting HSC proliferation, eg, SCF, cyclophosphamide |

| Prior chemotherapy | ||

| Melphalan | Direct HSC toxicity | Avoid melphalan until autologous cells collected |

| Fludarabine | Direct HSC toxicity, niche damage | Collect HSCs early, after < 4 cycles of fludarabine |

| Intensive chemotherapy (eg, hyper-CVAD) | Dose-dense cycles may cause niche damage, and HSCs forced into cell cycle may not engraft as well | Use SCF or preemptive risk-adapted plerixafor for fludarabine-exposed and heavily pretreated patients |

| Prior lenalidomide | Possible effects on HSC motility Possible dysregulated HSC niche because of antiangiogenic effects | Collect HSC early, after < 4 cycles of treatment Temporarily withhold lenalidomide during collection. |

Effect of underlying disease

BM involvement by disease is associated with poor yields.82,83 There may be reduced HSC numbers partly related to the impairment of healthy niches by malignant cells in the BM84 or direct competition between HSCs and malignant cells for a limited number of niches.85 Moreover, non-Hodgkin versus Hodgkin lymphoma,86 indolent lymphoproliferative disease,82 and acute leukemia87 have all been identified as independent risk factors. Whether there are specific aspects of the pathophysiology of these diseases that influence mobilization is still to be determined.

Effect of prior treatment

Mobilization failure in autologous donors correlates with the number of prior lines of treatment with chemotherapy. Most cytotoxic treatments and molecules used in targeted therapies can have deleterious effects on HSCs and the niches in which they reside. However, DNA cross-link agents such as melphalan or carmustine,88 and purine analogs such as fludarabine are associated with a very high risk of mobilization failure.89

Cytotoxic drugs that do not specifically target cell progressing through the S phase of the cell cycle (eg, anthracyclines, cisplatin, fludarabine, carmustine, melphalan) could potentially kill quiescent HSCs and niche cells, thereby reducing the HSC reserve. Fludarabine is toxic to hematopoietic progenitors as well as to the niche, a double hit on the mechanisms of mobilization.90 Alkylating agents such as chlorambucil given in a continuous manner may still be toxic on HSCs.

Highly intensive, dose-dense regimens such as the hyper-CVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone with methotrexate and cytarabine) regimen are associated with a high risk of mobilization failure beyond the first 2-4 cycles of therapy.91 Successive cycles of chemotherapy recruit more and more HSCs into the cell cycle, and in mice such forced HSC cycling leads to rapid exhaustion of HSC self-renewal and reconstitution potential. Repetitive cycles of chemotherapy may also damage niches for HSCs and BM macrophage effector cells.

Lenalidomide is associated with poor mobilization, particularly after > 4 cycles of treatment.92 Lenalidomide may suppress HSC motility similar to the way it reduces the motility of marrow endothelial cells in multiple myeloma.93 The antiangiogenic effect of lenalidomide could also impair mobilization.94

Long-term administration of imatinib has been associated with reduced bone turnover,95 which could affect HSC niche function. Yields were improved if the patients temporarily withheld imatinib for 3 weeks before collection.96

Prior radiotherapy to significant amounts of red marrow is associated with mobilization failure,97 probably because of combined direct HSC toxicity, niche toxicity, and toxicity to the niche-supporting cells. Radiotherapy may also increase the expression of protease inhibitors such as α1-antitrypsin that would diminish the protease storm during mobilization.98

Age-related poor mobilization

Poor mobilization is often noted in patients > 60 years of age.86,97 First, there is an age-related “senescence” of actual HSCs because of progressive telomere shortening.99 Second, there is a reduction in the HSC reserve caused by decreased niche function in older mice with depletion of mesenchymal stem cells and osteoprogenitors.100 Third, aging is frequently associated with a marked decrease in bone formation and osteoblast numbers on endosteal surfaces, so endosteal osteoblastic niches for HSCs are probably reduced.48,101

It is therefore noteworthy that boosting of bone turnover and formation with a 3-week course of daily injections of parathyroid hormone (PTH) increases HSC levels in mice102 and in a phase 1 clinical trial in patients who failed prior mobilization with G-CSF.103 However, the efficacy of PTH in mobilization is still to be proven. Interestingly, inhibition of bone degradation by a 5-day pretreatment with bisphosphonates such as pamidronate and zoledronate also increases HSC mobilization in response to G-CSF in mice.58,104

Failed mobilization in patients with no obvious risk factors: constitutive poor mobilizers

Up to 5% of healthy donors fail to mobilize with conventional regimens, and some patients with no obvious risk factors will also. The mechanistic understanding of these “constitutive poor mobilizers” is complex and incomplete. Different isogenic inbred mouse strains can have either very high or very low mobilizing response to G-CSF. Genetic linkage analyses in these inbred mouse strains have identified several loci linked to poor mobilization.105,106 The mechanisms could involve qualitative and quantitative differences in HSCs in the BM, a difference in how HSCs migrate, and how the niches are down-regulated in response to G-CSF.107 These genetic approaches have identified the epidermal growth factor receptor pathway and the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib as an adjuvant treatment to enhance mobilization in response to G-CSF in poorly responding mouse strains,107 although no human data are available. Genetic polymorphism analyses in humans have identified polymorphisms associated with mobilizing response to G-CSF in untranslated regulatory regions of genes encoding GCSFR, adhesion molecules (VCAM-1, CD44), and chemokines (SDF-1), which are all known to regulate HSC trafficking.108,109 Genetic polymorphisms may predict for poor mobilization, yet it is premature to apply such screenings in the clinic to identify poor mobilizers prospectively.

Strategies to optimize current mobilization protocols

Donor screening

The National Bone Marrow Program provides guidelines for screening of donors to ensure donor and recipient safety. Donors of male sex, young age, and match at A, B, C, DR, and DP are preferable because of higher HSC yield and more certain engraftment. If there were any concerns about myelodysplasia/leukemia or familial/inherited disorders, further screening investigations are warranted. For donors who failed to mobilize, the screening results should be reviewed and further investigations considered.

Planning of mobilization

For patients undergoing chemotherapy, collection of HSCs should be considered early when extensive or intensive chemotherapy such as hyper-CVAD are used and also before extensive use of fludarabine and lenalidomide. Lenalinomide and imatinib should be ceased 3 weeks before mobilization. It is intuitive that clearance of BM disease is desirable. For patients undergoing extensive field radiotherapy, “rainy day HSC harvesting” should be considered if autologous transplantation is a potential treatment option. Patients exhibiting markers of low HSC reserve such as baseline thrombocytopenia may benefit from regimens promoting HSC proliferation such as SCF or cyclophosphamide.

Optimizing apheresis to improve yield and to avoid weekend apheresis

The peripheral blood CD34+ cell count is the best predictor of apheresis yield,110 and the use of CD34+ cell counts to guide apheresis reduces costs.111 If the circulating CD34+ cell count is ≥ 20/μL, 94% of collections performed the following day would be expected to yield ≥ 2.0 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg.110 In general terms if the CD34+ cell count is < 5/μL, the yield will be poor; therefore, apheresis not warranted. If the count is > 10/μL, it may take ≤ 4 aphereses to collect sufficient cells for a single rescue.

Studies also showed that early and late progenitors tend to mobilize with similar kinetics112,113 and no CD34+ cell subsets provide additional information, so there is no need to measure different subsets.

In healthy donors mobilized with G-CSF alone peak CFU-GM and CD34+ cell counts occurred on day 5. The CD34+ cell peak was seen during days 4-6.114 In combined chemotherapy and G-CSF mobilization one study showed that mobilization occurred after day 11 after chemotherapy in 97% of patients, the median peak of CD34+ cell levels occurring on days 14-15, although heavily pretreated patients mobilized later.115 On the basis of these data, it is possible to schedule mobilization to avoid the costs of weekend apheresis and cryopreservation. For G-CSF alone mobilization, most centers would commence G-CSF on Friday and perform apheresis the following Tuesday onward. For combined chemotherapy and G-CSF mobilization, chemotherapy usually starts in the latter half of the week and G-CSF started the next few days. Peripheral blood CD34+ cell counts should be monitored when leukocyte recovery starts, aiming for apheresis Monday/Tuesday the week after. The CD34+ cell threshold for starting apheresis is derived through a combination of CD34+ cell yield target, the number of apheresis planned and the institutional experience with collection efficiency.116

Larger volume apheresis (processing ≥ 3 times the blood volume instead of 2 times) results in higher HSC yields and may reduce the number of sessions in some cases.117

Applying good manufacturing practice

For personnel training, quality assurance, and facility accreditation, the readers are referred to the FACT-JACIE International Standards for Cellular Therapy Products Collection, Processing and Administration118 and its accompanying Accreditation Manual119 produced by The Foundation for the Accreditation of Cellular Therapy (FACT) and the Joint Accreditation Committee of and International Society for Cellular Therapy European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (JACIE).

Strategies to improve the likelihood of success in poor mobilizers

Approaches to failed mobilization after conventional regimens include increased doses of G-CSF120 or combination with SCF.39,40,121,122 However, the success rate is often still < 50%. Currently, the combinations of G-CSF, SCF, or, more recently, plerixafor with or without chemotherapy are probably the most promising approaches.

Plerixafor

Plerixafor causes mobilization by disrupting of the SDF-1/CXCR4 interaction.123,124 It synergizes with G-CSF through its different mechanism of action. In clinical practice, plerixafor is usually administered subcutaneously at 240 μg/m2 in the evening 10-11 hours before the planned first day of apheresis. More recent publications describe successful use of plerixafor with dosing at 5:00 pm dosing the evening before apheresis.125 Peripheral blood CD34+ levels should be measured on the morning of apheresis, but commencement of apheresis should not be delayed. Two to 3 daily doses may be required in some patients.

In healthy donors plerixafor is effective as either a single agent or in combination with G-CSF.43 The safety and efficacy of plerixafor have been demonstrated in patients with lymphoma or multiple myeloma.126,127 However, the eventual cell yields with the use of up-front plerixafor in all patients were the same compared with the use of plerixafor only in those who failed G-CSF mobilization. The disadvantage of such up-front use of plerixafor is increased drug costs.

Outside the United States, the mode of reimbursement varied in different countries and requires user-pays in others. Yet remobilization and failed mobilization are also costly in terms of resources and patient outcome. Hence, it has been suggested that the biggest incremental benefit of plerixafor is in the poor mobilizer population.128 Risk-adapted algorithms have therefore been proposed: (1) preemptive plerixafor in predicted poor mobilizers, (2) immediate salvage plerixafor for patients with suboptimal mobilization, and (3) remobilization with plerixafor in failed mobilizers.

The rational use of preemptive plerixafor depends on identifying potential poor mobilizers. The adverse effect of BM involvement and prior chemo/radiotherapy have been discussed earlier, and low marrow cellularity probably reflects poor BM reserve.86 However, their specificity as an indicator is low because some of these patients may still mobilize. Steady state levels of circulating HSCs significantly correlate to CD34+ cell yield mobilized with conventional regimens,129 with yields of 1 × 106/kg CD34+ cells per apheresis procedure in 98% of patients with steady state CD34+ cell levels > 2.65/μL. However, it is not a reliable predictor of poor mobilization because 76% of patients below this threshold still had adequate mobilization.129 Whether a lower cutoff will be more useful is not known, but the reproducibility and reliability of measurement at such a lower level is at the limit of technology.

Requirement for G-CSF (when not given routinely) during previous chemotherapy130 may predict poor mobilization. Moreover, baseline thrombocytopenia (quoted thresholds range from < 100 to < 150 × 109/L)83,131 has been consistently associated with poor mobilization.

In healthy donors nearly 90% of donors who had a low TNF-α level in steady state exhibited suboptimal mobilization to a G-CSF alone regimen.132 Because TNF-α is an essential inflammation mediator produced by macrophages, the concentration of TNF-α may reflect BM macrophage activity which plays a crucial role in mobilization and niche maintenance.58,69

Overall, aside from baseline thrombocytopenia, there are as yet no indicators, singly or together, that identify poor mobilizers with certainty. Whether low TNF-α levels are predictive in the autologous setting is still unknown. Hence, choosing subjects for preemptive plerixafor requires clinician judgment.

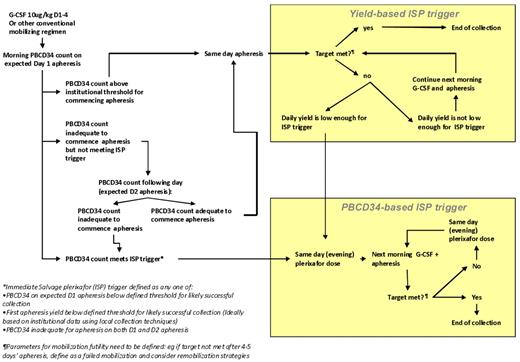

The rational use of immediate salvage plerixafor depends on real-time indicators to define “poor” and “slow” mobilizers during a mobilization attempt. These include a suboptimal peripheral blood (PB) CD34+ cell level or suboptimal apheresis yield or both at the expected first day of apheresis which predicts failure to collect the target yield within an acceptable number of apheresis days. There is as yet no validated data to define cutoffs for the addition of plerixafor; however, one published algorithm prescribes the addition of plerixafor on day 5 of G-CSF if the PB CD34+ level is < 10/μL when collecting cells for 1 transplantation, and < 20/μL when collecting cells for > 1 transplantation.125 However, it has been shown that a CD34+ cell level of < 5-6/μL on day 4 of G-CSF apheresis indicates the need for salvage plerixafor, because the likelihood of achieving a level > 10/μL by the following day is < 40%.133 A first-day apheresis yield of < 0.5 × 106 CD34+ cell/kg indicates need for salvage, although higher cutoffs such as a first-day apheresis of < 50% of the target yield are also used.125 Because institutional practices vary, individual centers ideally should analyze their own data to determine triggers for immediate salvage plerixafor that are based on different target cell yields (ie, cells for one or multiple transplantations), as defined by minimum CD34+ cell levels or day 1 apheresis CD34+ cell yields or both. A suggested protocol for immediate salvage plerixafor (ISP) is presented in Figure 3.

Example of a proposed risk-adapted protocol for ISP in the case of suboptimal mobilization response to a conventional regimen. Triggers for ISP can be based on peripheral blood CD34+ counts (PB CD34) or on the daily yield from the first day's apheresis.

Example of a proposed risk-adapted protocol for ISP in the case of suboptimal mobilization response to a conventional regimen. Triggers for ISP can be based on peripheral blood CD34+ counts (PB CD34) or on the daily yield from the first day's apheresis.

In failed mobilizers, a remobilization regimen with the addition of plerixafor enables reaching the CD34+ cell target in > 70% of patients128 so there is little doubt about its efficacy. One should ensure that there is ≥ 4 weeks of break before remobilization. Concerns have been raised about the higher nucleated cell content in the apheresis product affecting apheresis and increasing the infusion volume. This may be overcome by modifying the apheresis software.134

It is noteworthy that plerixafor-containing regimens have a 30% failure rate among prior failed mobilizers, probably because it could not restore low or defective HSC reserve or niche. Understanding how these factors operate at the molecular level and thereby steering the development of targeted approaches and alternative mobilization algorithms will define the next era of mobilization strategy.

Salvage BM harvest

Transplantation that use BM is generally associated with slower engraftment, particularly of platelets compared with that using mobilized HSCs. This problem is magnified in patients who mobilize poorly to current regimens, whereby the use of salvage BM-derived cells is associated with a particularly high incidence of delayed platelet engraftment and procedure-related deaths approaching 50%.135,136 Poor mobilizers probably have inherently low HSC numbers, possible functional HSC defects, as well as an unhealthy BM microenvironment which together amount to adverse conditions for engraftment, at times despite seemingly adequate CD34+ cell doses. Salvage BM harvests may be attempted in rare circumstances such as (1) refractory poor mobilization despite novel agents, (2) when these agents are unavailable, or (3) in the presence of contraindication to apheresis or stem cell mobilization regimens. In general, it is more advisable to seek enrollment on a clinical trial or a compassionate use program of a novel mobilization agent before resorting to salvage BM harvest.

Experimental agents for stem cell mobilization and their possible role in poor mobilizers

The role of CXCR4/SDF-1 inhibition is being further explored with alternative CXCR-4 antagonists such as POL6326 and BTK140 in early phase clinical trials in patients with multiple myeloma, both showing promise as mobilization agents for HSCs.137,138 Improved understanding of the HSC niche and HSC reserve has raised possibilities for restoring the niche with the use of agents such as SCF and parathyroid hormone.103 Other avenues for research include investigation of ways to trigger effector cells and pathways more efficiently such as through TNF-α, manipulation of the β-adrenergic circadian pulse (eg, harvesting HSCs in the afternoon, or pretreatment with β2 agonists), or optimizing macrophage-mediated pathways (eg, with Groβ). The recent description of S1P and ceramide-1 phosphate as chemoattractants for HSCs139 also raises possibilities for HSC mobilization. Natalizumab and other α4 integrin blockers may be useful in plerixafor failures.

Conclusion

Advances in the understanding of the mechanisms of mobilization have provided new insights into how poor mobilization can be prevented and managed. The avoidance of HSC and niche damage, the timing of mobilization, and the remarkable synergism between plerixafor and G-CSF plus chemotherapy are critical in optimizing the HSC yield that is fundamental to the safety and efficacy of HSCT. Plerixafor may be used in up-front, preemptive, immediate salvage and remobilization settings, and the most cost-effective protocols are still in development. More accurate predictors of poor mobilization are still sought, and the triggers for immediate salvage need to be developed for each site. These measures should be supported by rigorous and validated standard operating procedures of HSC harvesting and processing. Moreover, novel approaches that explore HSC expansion, β-adrenergic innervation, bone turnover, macrophage function, integrin blockade, and new chemotactic modulators may further improve HSC mobilization.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof John Rasko, Prof David Gottlieb, Dr Ian Lewis, Prof Jeff Szer, Dr Julian Cooney, and Dr Anthony Mills for helpful discussions. They also thank Dr Tony Cambareri and Ms Rachel Furno for their assistance with preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (grants 288701 and 434515, J.-P.L.) and a Cancer Council of Victoria Early Career Clinician Researcher grant (K.E.H.).

Authorship

Contribution: L.B.T, K.E.H., and J.-P.L. conceived, wrote, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Luen Bik To, Haematology, IMVS/SA Pathology, PO Box 14 Rundle Mall, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia; e-mail: bik.to@health.sa.gov.au.