Abstract

Nodular lymphocyte–predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) accounts for ∼ 5% of Hodgkin lymphoma cases. The disease is characterized by a strong CD20 expression on the malignant cells and a more indolent clinical course compared with classic HL. Anti-CD20 antibody treatment has shown clinical activity in relapsed NLPHL. In this phase 2 trial, we investigated rituximab in newly diagnosed stage IA NLPHL patients. Four weekly applications at 375 mg/m2 were given. Among the 28 evaluable patients, overall response rate was 100%, 24 patients (85.7%) achieved complete remission, and 4 (14.3%) achieved partial remission. At a median follow-up of 43 months, overall survival was 100%; progression-free survival at 12, 24, and 36 months was 96.4%, 85.3%, and 81.4%, respectively. No grade 3 or 4 toxicity was observed. Although treatment results with rituximab appear inferior compared with radiotherapy and combined-modality approaches in early-stage patients, investigation of anti-CD20 antibody-based combinations in NLPHL is warranted. This study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00346684.

Introduction

Nodular lymphocyte–predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) is a rare subtype of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) accounting for ∼ 5% of cases.1 The clinical course is usually more indolent than in classic HL (cHL), resulting in an excellent long-term prognosis. This is particularly true for patients diagnosed with early-stage NLPHL representing the majority of cases.2 However, current standard treatment consisting of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy (RT) is associated with an increased risk of late toxicity. Thus, there is a need for novel treatment strategies.

In contrast to cHL, CD20 is consistently expressed on the malignant lymphocyte-predominant (LP) cells in NLPHL.3 Anti-CD20 antibody treatment with rituximab has indicated impressive activity in relapsed NLPHL as shown by studies from the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) and the Stanford group.4,5

However, little is known on the role of anti-CD20 antibodies in the first-line treatment of NLPHL. The GHSG therefore conducted a single-arm phase 2 study to evaluate efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with newly diagnosed stage IA NLPHL. Results of the final analysis at a median follow-up of 43 months are reported.

Methods

Between June 2006 and October 2007, 29 patients from 23 sites were enrolled in this multicenter phase 2 trial. Study entry was restricted to adult patients (age, 18-75 years) with biopsy-proven stage IA NLPHL without clinical risk factors as defined by the GHSG. Risk factors included: (1) large mediastinal mass of more than one-third of the maximum thoracic diameter, (2) extranodal disease, (3) elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of > 50 mm/h, and (4) involvement of 3 or more nodal areas. NLPHL diagnosis was confirmed by expert review in 26 of 29 cases. One patient had to be excluded from the analysis because of composite lymphoma. No expert review was available for 2 patients. Treatment consisted of 4 weekly infusions of the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab at a dose of 375 mg/m2. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each study site; written informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Efficacy endpoints included remission status as assessed by computed tomography 4 weeks after completion of treatment, overall response rate, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival at 2 years; feasibility endpoints were acute treatment-related toxicities, adverse events, dose reductions, and therapy delays. Only descriptive analyses were planned in the study protocol. Nevertheless, a single-stage phase 2 design with a sample size of 29 patients was chosen to determine whether, based on the exact binomial distribution and a significance level of 5%, a true complete remission/complete remission unconfirmed (CR/CRu) rate of < 75% could be precluded in favor of presuming a true CR/CRu rate of 95%.

Results and discussion

Twenty-eight patients were included in the final analysis of this phase 2 trial; 71.4% of patients were male, 72% had supradiaphragmatic disease, and the median age was 40 years (Table 1). These characteristics are in line with previous reports on NLPHL patients.6

Baseline characteristics and outcome measures

| Characteristic . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics of 28 qualified patients* | |

| Median age, y (range) | 40 (19-68) |

| Sex, no. (%) | |

| Male | 20 (71.4) |

| Female | 8 (28.6) |

| Disease involvement,† no. (%) | |

| Infradiaphragmatic | 7/25 (28.0) |

| Supradiaphragmatic | 18/25 (72.0) |

| Remission status after lymph node biopsy,‡ no. (%) | |

| CR | 9/23 (39.1) |

| Residual disease | 14/23 (60.9) |

| Response to treatment§ | |

| Overall response, no. (%) | 28 (100.0) |

| CR/CRu | 24 (85.7) |

| Partial remission | 4 (14.3) |

| Tumor events,‖ no. (%) | |

| First relapse,¶ no. (%) | 7 (25.0) |

| Secondary malignancies,# no. (%) | 2 (7.1) |

| NLPHL relapse according to the remission status after lymph node biopsy‡ | |

| CR, no. (%) | 0/9 (0) |

| Residual disease, no. (%) | 7/14 (50.0) |

| Survival analyses | |

| Median observation time, mo (range) | 42.7 (38.0-44.5) |

| Progression-free survival, %, point estimate (CI) | |

| 1-year | 96.4 (89.6-100.0) |

| 2-year | 85.3 (71.9-98.6) |

| 3-year | 81.4 (66.6-96.1) |

| 4-year | 77.1 (60.9-93.3) |

| Overall survival | 100% |

| Characteristic . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics of 28 qualified patients* | |

| Median age, y (range) | 40 (19-68) |

| Sex, no. (%) | |

| Male | 20 (71.4) |

| Female | 8 (28.6) |

| Disease involvement,† no. (%) | |

| Infradiaphragmatic | 7/25 (28.0) |

| Supradiaphragmatic | 18/25 (72.0) |

| Remission status after lymph node biopsy,‡ no. (%) | |

| CR | 9/23 (39.1) |

| Residual disease | 14/23 (60.9) |

| Response to treatment§ | |

| Overall response, no. (%) | 28 (100.0) |

| CR/CRu | 24 (85.7) |

| Partial remission | 4 (14.3) |

| Tumor events,‖ no. (%) | |

| First relapse,¶ no. (%) | 7 (25.0) |

| Secondary malignancies,# no. (%) | 2 (7.1) |

| NLPHL relapse according to the remission status after lymph node biopsy‡ | |

| CR, no. (%) | 0/9 (0) |

| Residual disease, no. (%) | 7/14 (50.0) |

| Survival analyses | |

| Median observation time, mo (range) | 42.7 (38.0-44.5) |

| Progression-free survival, %, point estimate (CI) | |

| 1-year | 96.4 (89.6-100.0) |

| 2-year | 85.3 (71.9-98.6) |

| 3-year | 81.4 (66.6-96.1) |

| 4-year | 77.1 (60.9-93.3) |

| Overall survival | 100% |

NLPHL stage IA without risk factor (large mediastinal mass, extranodal disease, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, involvement of 3 or more nodal areas). One patient was not qualified because of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma diagnosis in addition to NLPHL at baseline.

Information is missing for 3 patients.

Information is missing for 5 patients.

Tumor status according to CT-based restaging 4 weeks after end of treatment.

Median observation time is 43 months.

Times to relapse since first NLPHL diagnosis were 9.6, 13.2, 14.4, 21.6, 26.4, 37.2, and 49.2 months, respectively.

Solid tumors: 1 adenocarcinoma of the colon 2 years after NLPHL diagnosis (male patient, 48 years) and 1 breast cancer 4 years after NLPHL diagnosis (female patient, 62 years).

Treatment was conducted in the outpatient setting in the majority of cases. Rituximab was well tolerated; no grade 3 or 4 toxicities were observed. Transfusions of erythrocytes or platelets were not required. The beneficial side effect profile appears comprehensible because NLPHL is a rather indolent disease and the tumor burden of patients included in this trial was low so that the occurrence of severe treatment-related effects, such as tumor lysis syndrome, was unlikely.

At final restaging 4 weeks after the last rituximab application, 24 patients (85.7%) were in CR/CRu and 4 patients (14.3%) had partial remission. Assuming a true CR/CRu rate of 75%, the probability of observing 24 of 28 patients with CR/CRu is P = .1354. Thus, despite of an overall response rate of 100%, the prespecified benchmark of 75% for insufficient efficacy cannot be precluded.

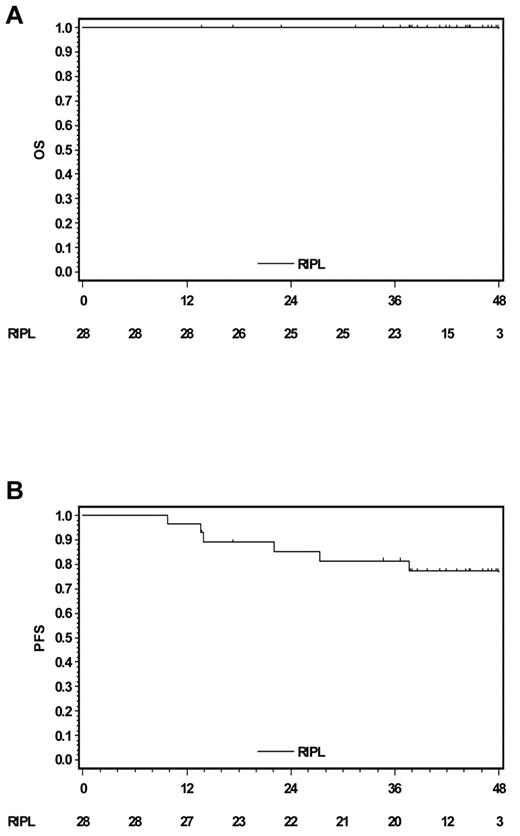

At a median follow-up of 43 months, all patients were still alive (Figure 1A). Seven patients (25%) have relapsed and 2 patients developed secondary solid tumors (Table 1). Relapses were biopsy-proven and restricted to the initially affected site in all but one patient who had stage II disease. Relapsed patients all belonged to the 60.9% of study participants who had residual disease after diagnostic lymph node resection (Table 1). This finding is consistent with the results of a report from Mauz-Körholz et al.7 Outcome of 58 children with early-stage NLPHL treated with resection only was analyzed. At 26 months, PFS among patients in CR after lymph node resection was 67%, whereas all patients with residual disease after surgery relapsed at a median of 17 months.7 Thus, resection alone might represent a treatment option in selected patients without residual lymphoma after surgery, but further studies are necessary for final conclusions.

Survival curves (Kaplan-Meier analyses). (A) Overall survival. (B) PFS.

Second-line treatment after rituximab failure consisted of RT alone in 4 patients; 1 patient received 4 cycles of adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) chemotherapy alone, and one patient was treated with another 4 doses of rituximab. Salvage treatment of 1 patient is unknown. All relapses were successfully salvaged. To date, no case of transformation into aggressive lymphoma occurred among patients included in this trial. This is worth mentioning because the actuarial risk of transformation from NLPHL into aggressive lymphoma was reported as 7% at 10 years and 30% at 20 years.8

The excellent response to rituximab observed in the present study was similar compared with reports on rituximab in relapsed NLPHL or patients with more advanced disease. A previous GHSG study investigating rituximab in 15 patients with relapsed NLPHL reported 14 responses.4 The Stanford group analyzed 22 NLPHL patients treated with rituximab. Ten of these patients had relapsed and 12 had newly diagnosed NLPHL. Overall response rate was 100%. However, at a median follow-up of 13 months, 9 of the 22 patients had relapsed.5

In the present study, PFS rate estimates at 2, 3, and 4 years were 85.3%, 81.4%, and 77.1%, respectively (Figure 1B). In a retrospective GHSG analysis on 131 early-stage NLPHL patients treated with RT only or combined-modality approaches, the freedom from treatment failure rate at 43 months was 95%.9 A more recent large single-center analysis, including 113 early-stage NLPHL patients (71 stage I, 42 stage II) with a median follow-up of 136 months among survivors, confirmed the excellent results achieved with RT alone. Clinical stage I patients had a 5-year PFS rate of 95%. However, secondary malignancy was the main cause of death among these patients treated with RT alone.10 This should be kept in mind, although current standard RT techniques potentially cause less long-term sequelae than those mostly applied in the reports mentioned herein.

In conclusion, the results of the present trial confirm the previously reported excellent response of NLPHL patients to rituximab. However, with a relapse rate of 25% at a median observation time of 43 months, rituximab does not seem to be as effective as RT alone or combined-modality strategies in stage IA NLPHL patients. Nonetheless, anti-CD20 antibodies have a favorable toxicity profile and may be offered to young patients who are at particular risk for long-term side effects, such as secondary malignancies. In addition, the combination of anti-CD20 antibodies and chemotherapy may also improve efficacy and decrease toxicity of NLPHL treatment in early unfavorable, advanced or relapsed disease.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all trial centers that participated in this trial. The study drug for this trial was provided by Hoffmann-La Roche, Grenzach-Whylen, Germany.

Authorship

Contribution: M.F., A.P., B.K., L.N., and A.E. provided conception and design; D.A.E., M.F., T.H., B.B., B.v.T., and P.B. provided administrative support; D.A.E., M.F., B.K., T.H., L.N., P.B., and A.E. provided study material or patients; D.A.E., M.F., A.P., and A.E. analyzed data and wrote the paper; and all authors collected and assembled data and provided final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: L.N. received a travel grant from Hoffmann-La Roche. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Andreas Engert, First Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital of Cologne, Kerpener Strasse 62, D-50937 Cologne, Germany; e-mail: a.engert@uni-koeln.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal