Abstract

The syndrome of monocytopenia, B-cell and NK-cell lymphopenia, and mycobacterial, fungal, and viral infections is associated with myelodysplasia, cytogenetic abnormalities, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, and myeloid leukemias. Both autosomal dominant and sporadic cases occur. We identified 12 distinct mutations in GATA2 affecting 20 patients and relatives with this syndrome, including recurrent missense mutations affecting the zinc finger-2 domain (R398W and T354M), suggesting dominant interference of gene function. Four discrete insertion/deletion mutations leading to frame shifts and premature termination implicate haploinsufficiency as a possible mechanism of action as well. These mutations were found in hematopoietic and somatic tissues, and several were identified in families, indicating germline transmission. Thus, GATA2 joins RUNX1 and CEBPA not only as a familial leukemia gene but also as a cause of a complex congenital immunodeficiency that evolves over decades and combines predisposition to infection and myeloid malignancy.

Introduction

We recently described a novel inherited immunodeficiency clinically characterized by disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial infections (typically Mycobacterium avium complex [MAC]), opportunistic fungal infections, disseminated human papilloma virus infections, and pulmonary alveolar proteinosis.1 Patients in multiple kindreds have profoundly decreased or absent monocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, and B cells and developed myelodysplasia (MDS), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Autosomal dominant inheritance and sporadic cases have been noted.1,2 The phenotype has been extended to include a severe decrease in circulating and tissue dendritic cells.2 Bone marrow hypocellularity and dysplasia of myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryocyte lineages are found in most patients, as are karyotypic anomalies, including monosomy 7 and trisomy 8.3 The syndrome of monocytopenia and mycobacterial infections, typically MAC, is clinically identified by history and routine laboratories and termed MonoMAC.3

Impaired development and differentiation of hematopoietic cells and the loss of several myeloid and lymphoid lineages transmitted in a dominant pattern focused our investigations on genes controlling hematopoietic stem cell development and maintenance, including RUNX1, PU.1, CEBPA, and ERG, all of which were wild-type. Recently, Scott et al4 reported 4 families with an autosomal dominant MDS/AML resulting from mutations in the critical hematopoietic regulator of stem cell integrity, GATA2. Their patients had onset of disease from their teens to 40s but were without problems before the rapid onset of MDS or AML.4 In their 4 families, they found mutations at 2 neighboring threonines (T354M and 355delT), both of which disrupt the second zinc finger (ZF-2) of GATA2 and act in a dominant negative fashion.

Methods

Patients clinically diagnosed with MonoMAC gave informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki for Institutional Review Board-approved protocols at the National Institutes of Health between 1996 and 2011. Genomic DNA was extracted from Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, cultured fibroblasts, or buccal swab samples from 18 probands and 2 affected relatives (PureGene Gentra DNA isolation kit, QIAGEN) and GATA2 was amplified (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Missense mutations were analyzed using PolyPhen25 to predict impact on structure and function of a protein.

Results and discussion

Although this syndrome was clearly Mendelian and associated with susceptibility to mycobacterial disease, mutations or dysfunction in the genes of the IFN-γ/IL-12 pathway were not found.1 Recognizing that the familial MDS/AML syndrome of Scott et al4 might overlap with the syndrome of MonoMAC because of the familial MDS/AML seen in a minority of our patients, we investigated GATA2 as a candidate gene for MonoMAC. DNA samples from 13 of the 16 kindreds in our original report were analyzed. Ten kindreds carried heterozygous mutations within the coding region of GATA2 (Table 1). In kindreds 1 and 13, the same mutation seen in the proband was identified in an affected relative, confirming germline transmission. The mother in kindred 13 had significantly reduced monocytes, B and NK cells, warts, and lymphedema but remains otherwise healthy. The patient in kindred 19 had fatal disseminated Mycobacterium massiliense and chronic active Epstein-Barr virus disease.

GATA2 mutations identified in MonoMAC patients

| Kindred* . | Patient* . | DNA change† . | Codon† . | Null‡ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.II.1 | c.1192 C → T | R398W | |

| 1 | 1.II.5 | c.1192 C → T | R398W | |

| 2 | 2.II.3 | c.1192 C → T | R398W | |

| 3 | 3.I.1 | c.1192 C → T | R398W | |

| 5 | 5.II.1 | c.1061 C → T | T354M | |

| 8 | 8.I.1 | c.243_244delAinsGC | G81fs | + |

| 9 | 9.III.1 | c.1192 C → T | R398W | |

| 10 | 10.1.1 | c.1113 C → G | N371K | |

| 12 | 12.I.1 | c.1083_1094del 12 bp | R361delRNAN | |

| 13 | 13.II.1 | c.1–200_871 + 527del 2033 bp | M1del290 | + |

| 13 | 13.I.2 | c.1–200_871 + 527del 2033 bp | M1del290 | + |

| 15 | 15.II.1 | c.1186 C → T | R396W | |

| 17 | c.1061 C → T | T354M | ||

| 18 | c.1187 G → A | R396Q | ||

| 19 | c.1061 C → T | T354M | ||

| 20 | c.778_779ins 10 bp | D259fs | + | |

| 21 | c.1192 C → T | R398W | ||

| 22 | c. 951_952ins 11 bp | N317fs | + | |

| 23 | c. 751 C → T | P254L | ||

| 24 | c. 1018–1 G → A | D340–381 |

| Kindred* . | Patient* . | DNA change† . | Codon† . | Null‡ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.II.1 | c.1192 C → T | R398W | |

| 1 | 1.II.5 | c.1192 C → T | R398W | |

| 2 | 2.II.3 | c.1192 C → T | R398W | |

| 3 | 3.I.1 | c.1192 C → T | R398W | |

| 5 | 5.II.1 | c.1061 C → T | T354M | |

| 8 | 8.I.1 | c.243_244delAinsGC | G81fs | + |

| 9 | 9.III.1 | c.1192 C → T | R398W | |

| 10 | 10.1.1 | c.1113 C → G | N371K | |

| 12 | 12.I.1 | c.1083_1094del 12 bp | R361delRNAN | |

| 13 | 13.II.1 | c.1–200_871 + 527del 2033 bp | M1del290 | + |

| 13 | 13.I.2 | c.1–200_871 + 527del 2033 bp | M1del290 | + |

| 15 | 15.II.1 | c.1186 C → T | R396W | |

| 17 | c.1061 C → T | T354M | ||

| 18 | c.1187 G → A | R396Q | ||

| 19 | c.1061 C → T | T354M | ||

| 20 | c.778_779ins 10 bp | D259fs | + | |

| 21 | c.1192 C → T | R398W | ||

| 22 | c. 951_952ins 11 bp | N317fs | + | |

| 23 | c. 751 C → T | P254L | ||

| 24 | c. 1018–1 G → A | D340–381 |

Numbering refers to patient and kindred numbers from Vinh et al.1

Numbering relative to adenine in the ATG start codon of GATA2 (GenBank NM_001145661.1) and the first methionine (GenBank NP_116027.2).

Predicted to result in loss of mRNA or protein from mutant allele.

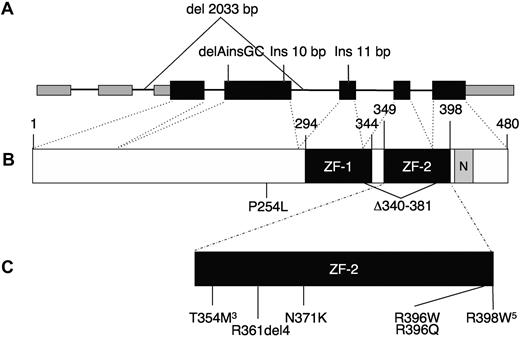

Eight patients not previously reported also carried heterozygous mutations (kindreds 17-24). All but one of the missense mutations are located within the highly conserved C-terminal zinc finger, ZF-2 (Figure 1). The remaining missense mutation is located before the zinc fingers; all are “probably damaging” by PolyPhen2.5 We identified 2 recurrent mutations, c.1061 C → T (T354M) in 3 unrelated patients (the same mutation described in 3 of the 4 families of Scott et al4 ) and the novel mutation c.1192 C → T (R398W) in 5 unrelated patients. Six patients had insertion/deletion mutations: an in-frame 4 amino acid deletion within the loop of the zinc finger (patient 12.I.1) and a mutation of the canonical splice acceptor for intron 5 predicted to cause a 42-amino acid in-frame deletion (proband, kindred 24). The remaining 4 insertion/deletion mutations are predicted to result in null alleles because of nonsense mediated decay, including one that deletes the coding exons 3 and 4, with the initial ATG and Kozak sequence (kindred 13).6 These insertion/deletion mutations suggest that haploinsufficiency of GATA2 may produce a phenotype similar to the dominant negative mutant GATA2 protein, T354M. None of the mutations, insertions, or deletions was present in dbSNP132, nor were they seen in 150 normal chromosomes sequenced. In 3 of the original kindreds, no GATA2 mutations have been identified.

GATA2 gene. (A) Genomic organization of GATA2 showing 2 5′-untranslated and 5 coding exons. Wider boxes represent coding regions. Insertion/deletion mutations predicted to result in null alleles are shown above. (B) Protein domains of GATA2, showing N- and C-terminal zinc fingers (ZF-1, ZF-2) and nuclear localization signal (N). (C) Missense and in-frame deletion mutations identified within ZF-2. Superscript numerals indicate the number of independent mutations.

GATA2 gene. (A) Genomic organization of GATA2 showing 2 5′-untranslated and 5 coding exons. Wider boxes represent coding regions. Insertion/deletion mutations predicted to result in null alleles are shown above. (B) Protein domains of GATA2, showing N- and C-terminal zinc fingers (ZF-1, ZF-2) and nuclear localization signal (N). (C) Missense and in-frame deletion mutations identified within ZF-2. Superscript numerals indicate the number of independent mutations.

Until recently, CEBPA7 and RUNX18 /CBFA29 were among the only reported genes with germline mutations known to cause familial MDS/AML. As in GATA2 deficiency, dominant inhibitory or haploinsufficient mutations in these genes have adverse consequences predisposing to development of MDS/AML and cytogenetic abnormalities.7-9 Like RUNX1 familial MDS/AML, we found both missense and null GATA2 mutations. The recently reported GATA2 mutated families of Scott et al4 with familial MDS/AML had no recognized pre-MDS or preleukemic phenotype. In contrast, our patients with GATA2 mutations typically had years of progressive opportunistic infections complicated by the development of multilineage cytopenias, bone marrow hypocellularity, and characteristic changes, including megakaryocyte dysplasia.3

Heterozygous GATA2+/− knockout mice have an increased percentage of quiescent Lin−ckit+Sca-1+ stem cells and increased apoptosis of Lin−ckit+Sca-1+ cells, resulting in a reduced hematopoietic stem cell pool.10 Bone marrow failure resulting from loss of stem cells may underlie the multilineage cytopenias in the MonoMAC syndrome, although they do not define a mechanism for cytogenetic abnormalities or the development of AML. Interestingly, mutations in GATA1 are responsible for both the transient myeloproliferative disorder and the acute megakaryocytic leukemia encountered in Down syndrome.11 In addition, GATA1 regulates GATA2 expression and can displace GATA2 from chromatin, the so-called GATA switch.12 Zhang et al reported a GATA2 gain-of-function somatic mutation, L359V, occurring in acute transformation of chronic myeloid leukemia.13 The recently described syndrome of homozygous recessive IRF8 deficiency lacked circulating monocytes and dendritic cells but had myeloid hyperplasia and histiocytes in the lymph node and osteoclasts in bone.14 Distinct from GATA2 deficiency, IRF8-deficient patients have normal B- and NK-cell numbers.14

The MonoMAC syndrome preceded by many years the development of overt MDS and was complicated by numerous features suggesting that tissue macrophages are critical in the control of both endogenous processes (pulmonary alveolar proteinosis) and opportunistic infections (nontuberculous mycobacteria, dimorphic molds, and human papillomavirus). GATA2 regulates phagocytosis by pulmonary alveolar macrophages, which may explain the common occurrence of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in MonoMAC.15 The significant human papillomavirus and other viral infections in the MonoMAC syndrome probably reflect the profound absence of NK cells in MonoMAC. The relatively narrow spectrum of infections is distinct from the neutropenia of MDS and draws a surprising connection between infection susceptibility and predeliction to myeloid malignancy. There is overlap in infections between this syndrome and IFN-γ/IL-12 defects, but those lesions are not associated with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis or MDS.16,17

These studies indicate that the MonoMAC syndrome is the result of mutations in GATA2. This novel genetic immunodeficiency has been recognized later in life than the vast majority of inborn immune defects and has multiple manifestations, including aplastic anemia, mycobacterial disease, fungal infections, warts, lung disease, human papillomavirus-associated squamous cell cancers, and MDS/AML. Given its high morbidity and mortality and its favorable response to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation,2,18 the ability to identify those at risk and to screen-matched, related donors for GATA2 mutations is critical. GATA2 apparently regulates previously unappreciated aspects of monocyte, macrophage, dendritic cell, B-cell, and NK-cell ontogeny, function, and circulation, as well as propensity to develop MDS, AML, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robin Stewart, Kristen Pike, and the Laboratory of Molecular Technology for sequencing assistance.

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (contract HHSN261200800001E).

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: A.P.H., J.K., D.C.V., S.Y.P., D.M.F., R.D.A., and J.S.O. performed experiments; A.P.H. and S.M.H. wrote the paper; E.P.S., J.K., K.R.C., J.E.L., D.M.F., A.F.F., K.N.O., G.U., B.E.M., J.C.G.-B., C.S.Z., C.S., M.L.P., J.C.-R., and D.D.H. provided clinical care and samples and revised the paper; S.P. and M.R. analyzed pathologic specimens; and D.B.K. and L.D. processed, preserved, and analyzed specimen.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for D.C.V. is Division of Infectious Diseases, McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, QC.

Correspondence: Steven M. Holland, Laboratory of Clinical Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, CRC B3-4141 MSC 1684, Bethesda, MD 20892-1684; e-mail: smh@nih.gov.