Abstract

In this study we investigated whether neoplastic transformation occurring in Philadelphia (Ph)–negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) could involve also the endothelial cell compartment. We evaluated the level of endothelial colony-forming cells (E-CFCs) in 42 patients (15 with polycythemia vera, 12 with essential thrombocythemia, and 15 with primary myelofibrosis). All patients had 1 molecular abnormality (JAK2V617F or MPLW515K mutations, SOCS gene hypermethylation, clonal pattern of growth) detectable in their granulocytes. The growth of colonies was obtained in 22 patients and, among them, patients with primary myelofibrosis exhibited the highest level of E-CFCs. We found that E-CFCs exhibited no molecular abnormalities in12 patients, had SOCS gene hypermethylation, were polyclonal at human androgen receptor analysis in 5 patients, and resulted in JAK2V617F mutated and clonal in 5 additional patients, all experiencing thrombotic complications. On the whole, patients with altered E-CFCs required antiproliferative therapy more frequently than patients with normal E-CFCs. Moreover JAK2V617F-positive E-CFCs showed signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 and 3 phosphorylation rates higher than E-CFCs isolated from healthy persons and patients with MPN without molecular abnormalities. Finally, JAK2V617F-positive E-CFCs exhibited a high proficiency to adhere to normal mononuclear cells. This study highlights a novel mechanism underlying the thrombophilia observed in MPN.

Introduction

During the embryonic development hematopoietic and endothelial cells arise from a mesoderm-derived common precursor called hemangioblast.1 The existence of an exceedingly rare hemangioblast progenitor has been shown also in the postnatal life in the CD34/KDR-positive cell subset.2 This cell appears to be endowed with long-term proliferative potential and with both hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation capacity.2 Because Philadelphia (Ph)–negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) show a high incidence of vascular complications3 and an endothelial cell dysfunction has been evidenced in patients with polycythemia vera (PV),4 several studies explored the possibility that the neoplastic transformation in MPN could involve also the endothelial cell compartment.5-9 On the whole, studies that were based on the in vitro assays for endothelial progenitors have identified JAK2V617F mutation or specific chromosome alterations only in endothelial progenitors derived from the hematopoietic lineage (the so-called colony forming unit-endothelial cells; CFU-ECs),5-7 whereas the true endothelial colony-forming cells, (E-CFCs) do not harbor genetic abnormalities.6,7 In conflict with these findings, Sozer et al8 found that endothelial cells isolated by microdissection from liver biopsies of patients with PV with Budd-Chiari Syndrome (BCS) exhibit the JAK2V617F mutation. In reality, granulocytes isolated from patients with MPN can harbor several genetic defects in addition to the JAK2V617F mutation, such as the hypermethylation of suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) genes10-12 or the presence of a clonal pattern of proliferation.13 Importantly, in some circumstances, these defects can be detected in the absence10,11 or even before the neoplastic clone acquired the JAK2V617F mutation.14-16 For these reasons, in this study we investigated endothelial progenitor cells isolated from patients with MPN for a large panel of molecular markers. Our results provided evidence that a subset of patients with MPN shows in endothelial progenitors the same molecular signatures detectable in the hematopoietic clone. Moreover, we found that the presence of JAK2V617F mutation into endothelial progenitors is associated with the hyper-phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (pSTAT-3) and STAT-5 (pSTAT-5), with an increased adhesion to normal mononuclear cells and, from a clinical point of view, with an increased risk of thrombosis.

Methods

Patients

This observational single-center study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional ethic committee of Catholic University. The cohort consisted of 42 patients with MPN (20 men and 22 women; median age, 58.5 years; range, 25-76; mean disease duration, 52 months; range, 6-140 months), recruited on an outpatient basis during the period of March 2008 to April 2010. The study inclusion criteria were (1) presence of detectable molecular markers in granulocytes, (2) absence of antiproliferative therapy at the time of the investigation (only phlebotomy or antiplatelet therapy or both were admitted). Seven patients were evaluated at diagnosis and 35 during the follow-up. Fifteen patients were affected by PV, 12 by essential thrombocythemia (ET) and 15 by primary myelofibrosis (PMF). All diagnoses were made according to criteria used at the time of the first evaluation and were revised according to World Health Organization 2008 diagnostic criteria.17 On the whole, 22 patients were JAK2V617F positive, 10 patients had both JAK2 mutation and SOCS gene hypermethylation, 5 patients had SOCS gene hypermethylation, and 1 patient had MPLW515K mutation and SOCS hypermethylation. Clinical and hematologic features of investigated patients are shown in Table 1. Twenty-five healthy blood donors (16 men and 9 women; median age, 37 years; range, 19-62 years) were investigated as the control group. Blood samples (30 mL) were collected after written informed consent.

Hematological and molecular findings of patients at their first evaluation

| . | Polycythemia vera (n = 15) . | Essential thrombocythemia (n = 12) . | Primary myelofibrosis (n = 15) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males/females, n | 9/6 | 4/8 | 9/6 |

| Age, y | |||

| Mean | 54.9 | 54.3 | 55 |

| Median (range) | 59 (27-70) | 56 (25-76) | 55 (31-72) |

| WBC count, × 109/L | |||

| Mean | 11.83 | 8.11 | 11.28 |

| Median (range) | 10.7 (6.70-18.00) | 7.50 (4.18-14.06) | 10.5 (4.3-24.1) |

| Hb, g/dL | |||

| Mean | 18.1 | 14 | 12.4 |

| Median (range) | 17.1 (14.8-24.8) | 14 (12.6-15.6) | 12.8 (7.9-19.4) |

| PLT count, × 109/L | |||

| Mean | 504 | 672 | 621 |

| Median (range) | 518 (205-849) | 604 (456-970) | 529 (58-2.696) |

| JAK2V617F or MPLW515K positive, n (%) | 13 (87) | 7 (58) | 11 (73) |

| SOCS methylation, n (%) | 5 (28) | 3 (27) | 8 (47) |

| . | Polycythemia vera (n = 15) . | Essential thrombocythemia (n = 12) . | Primary myelofibrosis (n = 15) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males/females, n | 9/6 | 4/8 | 9/6 |

| Age, y | |||

| Mean | 54.9 | 54.3 | 55 |

| Median (range) | 59 (27-70) | 56 (25-76) | 55 (31-72) |

| WBC count, × 109/L | |||

| Mean | 11.83 | 8.11 | 11.28 |

| Median (range) | 10.7 (6.70-18.00) | 7.50 (4.18-14.06) | 10.5 (4.3-24.1) |

| Hb, g/dL | |||

| Mean | 18.1 | 14 | 12.4 |

| Median (range) | 17.1 (14.8-24.8) | 14 (12.6-15.6) | 12.8 (7.9-19.4) |

| PLT count, × 109/L | |||

| Mean | 504 | 672 | 621 |

| Median (range) | 518 (205-849) | 604 (456-970) | 529 (58-2.696) |

| JAK2V617F or MPLW515K positive, n (%) | 13 (87) | 7 (58) | 11 (73) |

| SOCS methylation, n (%) | 5 (28) | 3 (27) | 8 (47) |

WBC indicates white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; and PLT, platelet.

CFU-EC and E-CFC colony assay

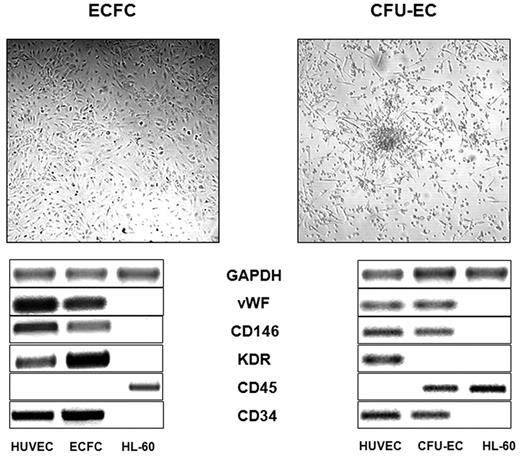

CFU-EC and E-CFC assays were performed according to the method of Hill et al18 and of Ingram et al,19 respectively, as previously described.20 Briefly, for CFU-EC colonies, Ficoll density gradient–isolated mononuclear cells were suspended in EndoCult medium (EndoCult Liquid Medium Kit, Stem Cell Technologies) and plated on 6-well dishes coated with human fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich). After 48 hours, nonadherent cells were recovered and replated in 24-well human fibronectin-coated dishes (Sigma-Aldrich) in the same culture medium, at 106/mL cell concentration. After an additional 3-5 days, aggregates consisting of multiple thin, flat cells emanating from a central cluster of rounded cells were counted as CFU-ECs. For the E-CFC colonies, mononuclear cells were suspended in endothelial cell growth medium-2 (EGM-2 Bulletkit; Lonza) on human fibronectin-coated 6-well dishes. At day 2 nonadherent cells were discharged, and residual adherent cells were grown in endothelial cell growth medium-2 for 28 days, with medium replacement every 3 days. Well-circumscribed monolayer of cobblestone-appearing cells growing from day 9 to day 28 were counted as E-CFCs and singly recovered. The true hematologic or endothelial nature of CFU-ECs and E-CFCs was investigated by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and the expression of von Willebrand factor, CD146, CD45, KDR, CD11b, and CD115, as described.9 The following primers were used: KDR, forward 5′-CCC ACG TTT TCA GAG TTG GT-3′ and reverse 5′-CTA CCG GTT TGC ACT CCA AT-3′; GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), forward 5′-AGG TGA AGG TCG GAG TCA ACG-3′ and reverse 5′-GCT CCT GGA AGA TGG TGAT GG-3′; von Willebrand factor, forward 5′-TAA GTC TGA AGT AGA GGT GG-3′ and reverse 5′-AGA GCA GCA GGA GCA CTG GT-3′; CD146, forward 5′-CCA AGG CAA CCT CAG CCA TGT C-3′ and reverse 5′-CTC GAC TCC ACA GTC TGG GAC GAC T-3′; CD34, forward 5′-TGA AGC CTA GCC TGT CAC CT and reverse 5′-CGC ACA GCT GGA GGT CTT AT; CD45, forward 5′-AAT GAG AAT GTG GAA TGT GG and reverse 5′-TTG CGT TAG TAA ACT TGT GG; CD115, forward 5′-CAC CAA GCT CGC AAT CCC-3′ and reverse 5′-CTC TAC CAC CCG GAA GAA CA-3′; CD11b, forward 5′-GCC GGT GAA ATA TGC TGT CT-3′ and reverse 5′-GCG GTC CCA TAT GAC AGT CT-3′. PCR conditions for amplification consisted in initial denaturation step at 94°C for 3 seconds, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 minute, 56°C for 1 minute, 72°C for 1 minute, and a final step at 72°C for 5 minutes. Representative CFU-EC and E-CFC colonies and their RT-PCR characterization are shown in Figure 1. Capillary formation assay was performed as described19,20 with the use of E-CFCs at passage 2. When appropriate, single E-CFC–derived colonies were expanded for 2 or 3 passages to obtain an amount of cells suitable for adhesion assays and for Western blot analysis.

Representative images of CFU-EC and E-CFC colonies and the typical RNA transcript, assessing the hematologic derivation of CFU-ECs and the true endothelial origin of the E-CFCs. GAPDH indicates glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; VWF, von Willebrand factor; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell.

Representative images of CFU-EC and E-CFC colonies and the typical RNA transcript, assessing the hematologic derivation of CFU-ECs and the true endothelial origin of the E-CFCs. GAPDH indicates glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; VWF, von Willebrand factor; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell.

JAK2 and MPL mutations

The presence of the JAK2V617F mutation was investigated according to the method of Baxter et al21 as previously described.22,23 Briefly, after DNA extraction with DNAzol (Invitrogen), following the product's protocol, 80 ng of DNA was used to assess the presence of the JAK2V617F mutation in allele-specific PCR. PCR products were separated onto 3% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light. A 203-base pair (bp) fragment indicated the presence of 1849G > T mutation. To determine whether the mutation was carried in the homozygous state, digestion of PCR products with BsaXI restriction enzyme was performed.22 Other functionally similar JAK2 exon 12 mutations were investigated by sequencing, according to the method of Scott et al24 in all JAK2V617F-negative patients. The presence or the absence of the JAK2 mutation was confirmed by direct sequencing with the use of the external primers described in the method of Baxter et al12 . The presence of MPL mutations (MPLW515L and MPLW515K) was investigated by sequencing, using the same primers and PCR conditions previously described.23

JAK2V617F allele burden

The mutant allele burden was measured by a quantitative real-time PCR assay, following the methods previously reported.25 All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Human androgen receptor analysis

The clonal pattern of growth was assessed by the HUMARA polymorphism assay and by the HUMARA methylation-specific PCR (MS-PCR) in granulocytes and in pooled E-CFCs isolated from female patients, as previously described.22 T lymphocytes were used as control. Briefly, 1 μg of DNA was incubated with and without 20 U of HpaII (New England Biolabs) at 37°C for 12 hours. After 10 minutes of incubation at 95°C, 3 μL of all samples was amplified with specific primers as previously described.22 Results obtained by the HUMARA polymorphism assay were confirmed by HUMARA MS-PCR analysis. Briefly, after treatment of 1 μg of DNA with sodium bisulfate, purification, and desulfonation with sodium hydroxide, DNA was amplified with specific primers for the methylated and unmethylated HUMARA gene.23 PCR amplification and correction of the ratio of peaks for an appropriate X-inactivation pattern were performed with the ABI PRISM 3100Avant Genetic Analyzer and GeneMapper ID software (Applied Biosystems).

MS-PCR for SOCS-1, SOCS-2, and SOCS-3 cytosine-phosphate-guanosine islands

Methylation status of SOCS-1, SOCS-2 and SOCS-3 cytosine-phosphate-guanosine islands was investigated by MS-PCR as described.11 Genomic DNA (1 μg) was subjected to bisulfite modification with the use of EpiTect Bisulphite kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer's protocol, and then amplified in a mixture containing PCR buffer containing primers (20pM each) and 0.25 U of GoTaq polymerase (Promega).11 PCR products were electrophoresed in a 2.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light. DNA isolate from normal lymphocytes, hypermethylated with SssI methyltransferase (New England Biolabs), and subsequently modified with bisulfite was used as unmethylated and methylated controls; water was used as negative control; unmodified DNA was used as internal control of MS-PCR. All samples that resulted in methylation were subjected to sequencing, either directly or after subcloning.11 Briefly, the PCR products were cloned into a pGEM-T easy vector system (Promega) with the use of JM109 high-efficiency competent cells. Five randomly picked clones were sequenced on an ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Western blot analysis of pSTAT-3 and pSTAT-5

In selected experiments, E-CFCs recovered in each patient were pooled and evaluated for the expression of pSTAT-3 and pSTAT-5, as described.22 Briefly, after cell lysis, supernatant proteins were recovered, dissolved in sodium dodecylsulfate sample buffer, boiled for 5 minutes, and then separated on sodium dodecylsulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Gels were blotted with transfer buffer directly on pure nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) at 330 mA for 1 hour. After not specific binding sites blocking, blots were probed with an anti–pSTAT-3 (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–pSTAT-5 (1:500; BD Biosciences), and anti-actin (Ab-5, 1:5000; BD Biosciences) mouse monoclonal antibodies. Blots were the incubated with goat anti–mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated antiserum (1:1000; BD Biosciences), covered with enhanced chemiluminescence solutions for 1 minute (Western blotting analysis system; GE Healthcare) and exposed to Kodak XAR-5 x-ray film (Kodak). Precipitates were subjected to densitometric analysis with the use of the Gel-Doc 2000 Quantity One program (Bio-Rad), after normalization with the actin intensity.

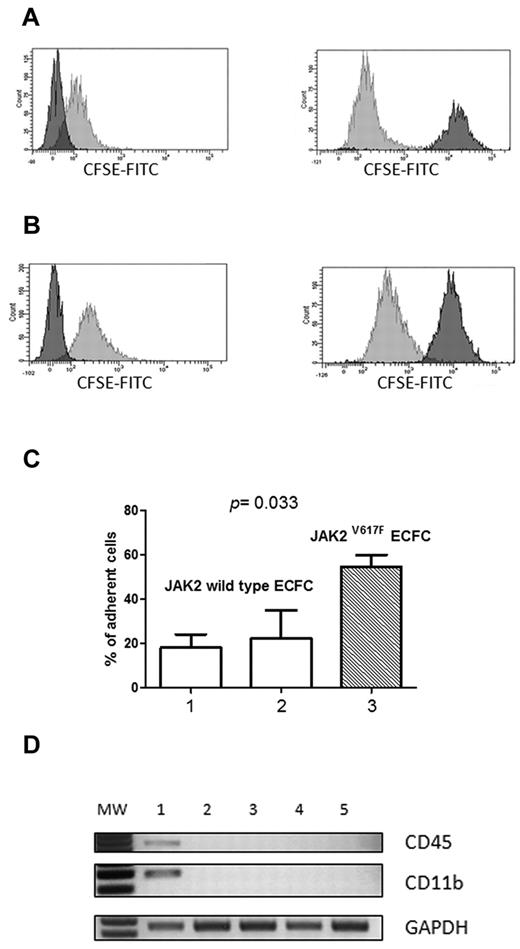

Mononuclear and endothelial cell adhesion assay

E-CFCs obtained from healthy donors and from patients were grown to confluence and were assayed for the adhesion to normal mononuclear cells. Briefly, normal mononuclear cells isolated from healthy donors were divided in 2 aliquots; one of them was labeled with 0.2μM/106 cells of CellTrace carboxyfluorescein diacetate succynimidyl ester (CFSE; Invitrogen) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% of fetal bovine serum, for 15 seconds at 37°C in darkness. The surplus of CFSE was discharged by repeated washes with PBS. Mononuclear cells exposed or not (as negative control) to CFSE staining were then plated over confluent E-CFCs in 6-well plates, at a concentration of 106 cells/well and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Nonadherent cells were then removed by 3 courses of gentle PBS washing. Mononuclear cells adherent to E-CFCs were then detached from the well bottom together with E-CFCs by trypsin (Lonza). The cell suspension was then analyzed by flow cytometry at a 488-nm excitation source (FACSCanto 4; BD Biosciences). CFSE-positive cells were defined after detracting the autofluorescence of the negative control. Results are expressed as the percentage of CFSE-positive cells over total counted events. To exclude that enhanced cell-to-cell adhesion properties in vivo may have led to hematopoietic-endothelial cell fusion in vitro, after the adhesion assay, aliquots of E-CFCs were analyzed for the mRNA expression of hematopoietic-specific antigens (CD45 and CD11b), both at early and late passages.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with using GraphPad Prism (Version 5.00 for Windows; GraphPad Software Inc). All P values were 2-tailed, and statistical significance was set at the level of P < .05. Comparison between categorical variables was performed by χ2 statistics. Comparison between continuous variables was performed by either the Mann-Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis test. Survival curves were obtained by the Kaplan-Meier method and then compared through the log-rank test.

Results

CFU-EC and E-CFC recovery

Table 2 shows the frequency of CFU-ECs and E-CFCs in patients with MPN in comparison with healthy persons. In general, patients with MPN exhibited a low level of CFU-ECs (P = .048 in comparison with healthy controls at the Kruskal-Wallis test). Moreover, the level of CFU-ECs in patients with MPN experiencing thrombosis was significantly lower than in patients without thrombosis (median value/106 plated cells, 0 ± 0.5 versus 3 ± 1, respectively; P = .027). Conversely, the frequency of E-CFCs was higher in patients with patients than in healthy controls, although the differences were statistically significant only for the PMF group (P = .0078). Among patients with MPN, 6 of 15 patients with PV, 6 of 12 patients with ET, and 10 of 15 patients with PMF showed E-CFC growth (Table 2). The levels of CFU-ECs and E-CFCs that we observed in our series of patients and in healthy controls and the percentage of samples producing ≥ 1 E-CFC colony are in good agreement with those reported by other investigators that used the same methods.6

E-CFC frequency in healthy blood donors and in patients with MPN grouped according to the diagnosis

| . | Controls . | PV . | ET . | PMF . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFU-EC, 106 cells, median (range) | 4.9 (0-42.5) | 0.75 (0-15.8) | 1.2 (0-6.5) | 0.7 (0-20.7) |

| E-CFC, 107 cells, median (range) | 0.1 (0-0.8) | 0.1 (0-6.7) | 0 (0-9.6) | 0.8 (0-8) |

| Samples with ≥ 1 E-CFC, n/N | 14/25 | 6/15 | 6/12 | 10/15 |

| . | Controls . | PV . | ET . | PMF . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFU-EC, 106 cells, median (range) | 4.9 (0-42.5) | 0.75 (0-15.8) | 1.2 (0-6.5) | 0.7 (0-20.7) |

| E-CFC, 107 cells, median (range) | 0.1 (0-0.8) | 0.1 (0-6.7) | 0 (0-9.6) | 0.8 (0-8) |

| Samples with ≥ 1 E-CFC, n/N | 14/25 | 6/15 | 6/12 | 10/15 |

Patients with PMF showed a higher E-CFC frequency than controls (P = .0078).

MPN molecular markers in CFU-ECs and E-CFCs

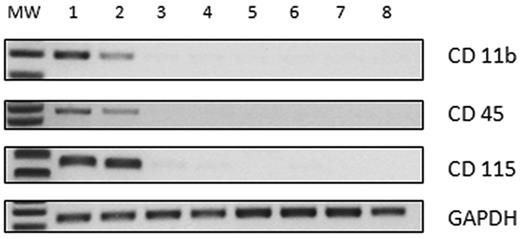

Among the 22 patients showing the growth of ≥ 1 E-CFC, 11 were JAK2V617F mutated, 5 presented with both JAK2V617F mutation and SOCS gene hypermethylation, 1 patient had MPLW515K mutation and SOCS gene hypermethylation, and 5 patients had SOCS gene hypermethylation (Table 3). Ten patients were women and could be evaluated also for the human androgen receptor analysis (HUMARA) assay. According to their hematologic signature and to confirm previous findings from other groups,6,7 we found that CFU-ECs in these patients always exhibited the same molecular markers as granulocytes (data not shown). In contrast, the behavior of E-CFCs was variable, and we could identify 3 groups of patients (Table 3). On the whole, the mean number of assayed E-CFCs for each patient was 7 in the first group, 5 in the second group, and 9 in the third group (P = .14). The first group included 12 patients who had normal E-CFCs, lacking those MPN molecular alterations observed in the respective granulocyte samples (Table 3). In 3 of these patients, we evidenced that the pattern of growth of E-CFCs was polyclonal at the HUMARA assay. Conversely, E-CFC progenitors obtained from the remaining 10 patients exhibited molecular myeloproliferative signatures. In particular, E-CFCs collected from 5 patients (13-17; Table 3) showed a pattern of SOCS gene hypermethylation overlapping that found in the respective granulocytes; in particular SOCS-1 gene was involved in 3 cases (patients 14, 15, and 17; Table 3), SOCS-2 in 1 case (patient 13, Table 3), and both SOCSC-1 and SOCS-2 in 1 case (patient 16; Table 3). Interestingly, although 3 of them were JAK2V61F positive and 1 was MPLK515L positive, these mutations were not detected in E-CFCs. In one case (patient 13; Table 3) we found E-CFCs both unmethylated (1 colony) and methylated (4 colonies). When these colonies were pooled and assayed for the HUMARA, they appeared polyclonal. Indeed, these observations show evidence that in this patient normal endothelial progenitors may persist and circulate. Finally, the third group included 5 patients exhibiting the growth of JAK2V61F-positive E-CFCs (patients 18-22; Table 3). All the examined E-CFCs were JAK2V61F-positive, and no JAK2 wild-type colonies were observed. The burden of the JAK2V61F allele in each examined E-CFC was variable from colony to colony and ranged from 30% to 74% (median value, 52%). Moreover, in 4 patients, the HUMARA assay performed on pooled E-CFCs documented that endothelial progenitors were clonally related (Table 3). These findings suggest that, in this subgroup of patients, the endothelial progenitor cell compartment is entirely involved by the neoplastic transformation, whereas each progenitor might exhibit variable proportions of wild-type and mutated alleles. The detection of SOCS gene hypermethylation and of JAK2V617F mutation in E-CFCs was confirmed after expanding additional colonies for 2 or 3 passages. Finally, we rule out the possibility that the detection of MPN molecular signatures in E-CFCs could result from the in vivo hematopoietic-endothelial cell fusion. Actually, we demonstrated that JAK2V617F E-CFCs isolated from 3 patients with MPN, evaluated at both early and late passages, do not express myeloid lineage–associated antigens (CD45, CD115, and CD11b) (Figure 2).

Myeloproliferative molecular markers detected in granulocytes and in E-CFCs isolated from patients with MPN

| Patient . | Diagnosis . | Thrombosis . | Granulocytes . | E-CFCs . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JAK2 . | SOCS methylation . | HUMARA . | Colonies assayed . | JAK2 . | SOCS methylation . | HUMARA . | |||

| 1 | PMF | No | wt | Yes | Polyclonal | 20 | wt | No | Polyclonal |

| 2 | PMF | No | V617F | No | NE | 7 | wt | No | NE |

| 3 | PMF | No | V617F | Yes | NE | 2 | wt | No | NE |

| 4 | PV | No | V617F | Yes | NE | 3 | wt | No | NE |

| 5 | ET | No | wt | Yes | NE | 10 | wt | No | NE |

| 6 | PMF | No | wt | Yes | NE | 2 | wt | No | NE |

| 7 | PMF | No | V617F | Yes | NE | 14 | wt | No | NE |

| 8 | ET | No | V617F | No | NE | 3 | wt | No | NE |

| 9 | ET | No | V617F | No | Clonal | 7 | wt | No | Polyclonal |

| 10 | PV | No | V617F | No | Clonal | 5 | wt | No | Polyclonal |

| 11 | PV | No | V617F | No | NE | 11 | wt | No | NE |

| 12 | PV | No | V617F | No | Clonal | 2 | wt | No | NE |

| 13 | ET | No | V617F | Yes | NE | 1 | wt | Yes | NE |

| 14 | PV | No | wt | Yes | NE | 3 | wt | Yes | NE |

| 15 | ET | No | V617F | Yes | Polyclonal | 2 | wt | Yes | NE |

| 16 | PMF | No | wt* | Yes | Clonal | 5 | wt* | Yes | Polyclonal |

| 17 | PMF | No | V617F | Yes | NE | 4 | wt | Yes | NE |

| 18 | PMF | PT | V617F | No | Clonal | 21 | V617F | No | Clonal |

| 19 | ET | BCS | V617F | No | Clonal | 10 | V617F | No | Clonal |

| 20 | PMF | PE, DVT | V617F | No | NE | 2 | V617F | No | NE |

| 21 | PMF | DVT | V617F | No | Clonal | 6 | V617F | No | Clonal |

| 22 | PV | Stroke | V617F | No | Clonal | 10 | V617F | No | Clonal |

| Patient . | Diagnosis . | Thrombosis . | Granulocytes . | E-CFCs . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JAK2 . | SOCS methylation . | HUMARA . | Colonies assayed . | JAK2 . | SOCS methylation . | HUMARA . | |||

| 1 | PMF | No | wt | Yes | Polyclonal | 20 | wt | No | Polyclonal |

| 2 | PMF | No | V617F | No | NE | 7 | wt | No | NE |

| 3 | PMF | No | V617F | Yes | NE | 2 | wt | No | NE |

| 4 | PV | No | V617F | Yes | NE | 3 | wt | No | NE |

| 5 | ET | No | wt | Yes | NE | 10 | wt | No | NE |

| 6 | PMF | No | wt | Yes | NE | 2 | wt | No | NE |

| 7 | PMF | No | V617F | Yes | NE | 14 | wt | No | NE |

| 8 | ET | No | V617F | No | NE | 3 | wt | No | NE |

| 9 | ET | No | V617F | No | Clonal | 7 | wt | No | Polyclonal |

| 10 | PV | No | V617F | No | Clonal | 5 | wt | No | Polyclonal |

| 11 | PV | No | V617F | No | NE | 11 | wt | No | NE |

| 12 | PV | No | V617F | No | Clonal | 2 | wt | No | NE |

| 13 | ET | No | V617F | Yes | NE | 1 | wt | Yes | NE |

| 14 | PV | No | wt | Yes | NE | 3 | wt | Yes | NE |

| 15 | ET | No | V617F | Yes | Polyclonal | 2 | wt | Yes | NE |

| 16 | PMF | No | wt* | Yes | Clonal | 5 | wt* | Yes | Polyclonal |

| 17 | PMF | No | V617F | Yes | NE | 4 | wt | Yes | NE |

| 18 | PMF | PT | V617F | No | Clonal | 21 | V617F | No | Clonal |

| 19 | ET | BCS | V617F | No | Clonal | 10 | V617F | No | Clonal |

| 20 | PMF | PE, DVT | V617F | No | NE | 2 | V617F | No | NE |

| 21 | PMF | DVT | V617F | No | Clonal | 6 | V617F | No | Clonal |

| 22 | PV | Stroke | V617F | No | Clonal | 10 | V617F | No | Clonal |

wt indicates wild type; NE, not evaluable; PT, portal vein thrombosis; BCS, Budd-Chiari syndrome; PE, pulmonary embolism; and DVT, deep vein thrombosis of the legs.

This patient carried the MPLK515L mutation.

RNA expression (RT-PCR) of myeloid lineage–associated antigens (CD45, CD115, and CD11b) and GAPDH (internal control). Lane 1, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (positive control); lane 2, CFU-ECs from healthy control; lanes 3-5, E-CFCs at passages I obtained in 3 different patients with JAK2V617F E-CFCs; lane 6-8, E-CFCs at passages IV obtained from the same 3 patients. MW indicates molecular weight marker (50 base pair); GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

RNA expression (RT-PCR) of myeloid lineage–associated antigens (CD45, CD115, and CD11b) and GAPDH (internal control). Lane 1, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (positive control); lane 2, CFU-ECs from healthy control; lanes 3-5, E-CFCs at passages I obtained in 3 different patients with JAK2V617F E-CFCs; lane 6-8, E-CFCs at passages IV obtained from the same 3 patients. MW indicates molecular weight marker (50 base pair); GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Clinical characteristics of patients grouped according to E-CFC findings

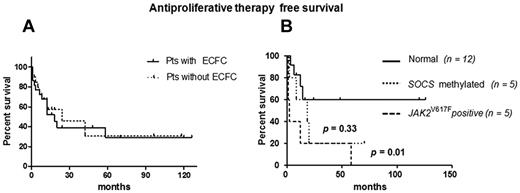

Overall, among 42 patents investigated, 10 experienced thrombosis (2 portal thrombosis, 4 deep vein thrombosis, 1 deep vein thrombosis with pulmonary embolism, 1 transient ischemic attack, 1 stroke, 1 BCS) and 23 required antiproliferative therapy (hydroxyurea or interferon). The criteria for starting therapy were history of thrombosis (10 patients), splenomegaly (4 patients), failure of phlebotomy in lowering hematocrit (6 patients), age > 65 years (2 patients), platelet count > 1500 × 109/L (1 patient). First, we evaluated if the ability to produce E-CFCs could identify a particular subset of patients with MPN, having peculiar clinical or hematologic features. The 2 groups of patients (22 with and 20 without E-CFCs) were comparable for age, diagnosis, and sex distribution; hematologic findings at the first observation (data not shown); and disease duration (mean, 49 ± 9 months vs 54 ± 9 in patients with and without E-CFC growth, respectively; P = .52). No differences were found for the presence of SOCS gene hypermethylation (P = .12), of JAK2V617F mutation (P = .72), and of JAK2V617F allele burden (P = .79); we did not observe a different incidence of thrombosis (P = .53). Moreover, the proportion of patients requiring antiproliferative therapy (P = .72) and the antiproliferative therapy–free survival were similar in both groups (P = .75; Figure 3A). Indeed, we focused on the 22 patients showing the E-CFC growth, grouped as having normal E-CFC, hypermethylated E-CFCs, or JAK2V617F-positive E-CFCs. We did not find differences among the 3 groups for age, diagnosis, and sex distribution (data not shown); disease duration (mean, 59 ± 14 months in patients with normal E-CFCs, 45 ± 15 in patients with hypermethylated E-CFCs, and 53 ± 17 months in patients with JAK2V617F E-CFCs, respectively; P = .98); and percentage of JAK2-mutated subjects (P = .32). Nevertheless, compared with patients with JAK2 wild-type E-CFCs, those with JAK2-mutated E-CFCs exhibited higher incidence of thrombosis (P < .0001), higher JAK2V61F allele burden (mean, 70 ± 6 vs 39 ± 8, respectively; P = .022), and higher leukocyte count (15.95 ± 2.43 × 109/L vs 8.64 ± 0.8 × 109/L, respectively; P = .007). Among patients requiring antiproliferative therapy (13 cases), 5 showed JAK2-mutated E-CFCs and 4 showed SOCS-methylated E-CFCs (P = .011). Finally, the median antiproliferative drug–free survival was 2 months for patients exhibiting JAK2-mutated E-CFCs, 18 months for those with hypermethylated E-CFCs, whereas it was not reached in patients without molecular abnormalities (P = .013 at the log-rank test in comparison with patients with JAK2-mutated E-CFCs; Figure 3B).

Antiproliferative therapy–free survival. (A) Comparison between patients showing or not the E-CFC growth (P = .75). (B) Comparison among the different groups of patients showing the E-CFC growth according to the molecular signatures found in E-CFC progenitors.

Antiproliferative therapy–free survival. (A) Comparison between patients showing or not the E-CFC growth (P = .75). (B) Comparison among the different groups of patients showing the E-CFC growth according to the molecular signatures found in E-CFC progenitors.

Functional characterization of altered endothelial progenitors

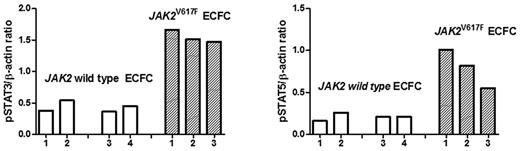

The presence of JAK2 mutation and clonality (but not of SOCS gene hypermethylation) in E-CFCs was associated with an increased incidence of vascular complications. Indeed, we first evaluated if the JAK2V617F mutation in these cells induced an increased phosphorylation of the downstream STAT pathway in respect to endothelial progenitors with wild-type JAK2. To this purpose, Western blot analysis for pSTAT-3 and pSTAT-5 was carried out in endothelial progenitors expanded from 2 healthy persons, from 2 patients with MPN showing no abnormalities in their E-CFCs, and from 3 patients exhibiting the growth of JAK2V617F-mutated colonies. Results obtained are reported in Figure 4 and show that the JAK/STAT pathway is exaggeratedly activated in cells originating from abnormal progenitors, whereas both STAT-3 and STAT-5 exhibited a low phosphorylation rate in E-CFCs isolated from healthy persons and in patients with MPN with E-CFCs showing no molecular abnormalities. For this reason we investigated by the Matrigel assay the ability of JAK2V617F-mutated E-CFCs to form tubes in vitro, but, as previously reported for JAK2 wild-type E-CFCs isolated from patients with MPN,6 we did not find differences in respect to E-CFCs obtained from healthy controls (data not shown), suggesting that molecular abnormalities do not affect their angiogenetic ability. To further explore the effect of JAK2V617F mutation on endothelial cell function, we evaluated the ability of endothelial cells to adhere to normal mononuclear cells. The representative experiments performed in a healthy control and in a patient with JAK2V617F-positive E-CFCs are shown in Figure 5A and B, respectively. The percentages of mononuclear cells adherent to E-CFCs acquired from healthy controls and from patients are shown in Figure 5C (mean values of experiments performed with 2 JAK2 wild-type E-CFCs and 4 JAK2V617F E-CFCs). Actually, JAK2V617F-mutated E-CFCs showed a significantly higher adhesion proficiency to mononuclear cells than normal E-CFCs (P = .033). Finally, to evaluate whether the JAK2V617F E-CFCs might have bound mononuclear cells in the coculture adhesion assay, we evaluated the expression of CD45 and CD11b either at first passage after the adhesion assay and thereafter at late passages, and we found that it was always absent (Figure 5D).

Expression of pSTAT-3 and pSTAT-5 in E-CFCs isolated from 2 healthy persons (1 and 2), from 2 patients with JAK2 wild-type E-CFCs (3 and 4), and in JAK2V627F-mutated E-CFCs obtained from 3 patients (5-7). Values are expressed in arbitrary units as the ratio of the densitometric analysis between pSTAT-3 and pSTAT-5 and the respective β-actin bands.

Expression of pSTAT-3 and pSTAT-5 in E-CFCs isolated from 2 healthy persons (1 and 2), from 2 patients with JAK2 wild-type E-CFCs (3 and 4), and in JAK2V627F-mutated E-CFCs obtained from 3 patients (5-7). Values are expressed in arbitrary units as the ratio of the densitometric analysis between pSTAT-3 and pSTAT-5 and the respective β-actin bands.

CFSE-labeled mononuclear cell adhesion to E-CFCs. Representative experiments showing (left) the cytofluorimetric analysis of unstained peripheral blood mononuclear cells (negative control) and (right) the number of CFSE-labeled mononuclear cells bound by E-CFCs (A) in a healthy control and (B) in a patient with JAK2V617F-positive E-CFCs. (C) Percentages of mononuclear cells adherent to normal E-CFCs (plot 1, mean values ± SEM of 4 healthy controls), to JAK2 wild-type E-CFC (plot 2, mean values ± SEM of 2 patients), and to JAK2V627F-mutated E-CFCs (plot 3, mean values ± SEM of 4 patients). (D) RNA expression (RT-PCR) of CD45, CD11b, and GAPDH (internal control) in E-CFCs recovered from the adhesion assay, at early or late passages. Lane 1 shows peripheral blood mononuclear cells (positive control); lanes 2 and 3, JAK2 wild-type E-CFCs isolated from a patient with MPN at passages I and IV; lanes 4 and 5, JAK2V617F E-CFCs at passages I and IV. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; MW, molecular weight marker (50 base pair); GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

CFSE-labeled mononuclear cell adhesion to E-CFCs. Representative experiments showing (left) the cytofluorimetric analysis of unstained peripheral blood mononuclear cells (negative control) and (right) the number of CFSE-labeled mononuclear cells bound by E-CFCs (A) in a healthy control and (B) in a patient with JAK2V617F-positive E-CFCs. (C) Percentages of mononuclear cells adherent to normal E-CFCs (plot 1, mean values ± SEM of 4 healthy controls), to JAK2 wild-type E-CFC (plot 2, mean values ± SEM of 2 patients), and to JAK2V627F-mutated E-CFCs (plot 3, mean values ± SEM of 4 patients). (D) RNA expression (RT-PCR) of CD45, CD11b, and GAPDH (internal control) in E-CFCs recovered from the adhesion assay, at early or late passages. Lane 1 shows peripheral blood mononuclear cells (positive control); lanes 2 and 3, JAK2 wild-type E-CFCs isolated from a patient with MPN at passages I and IV; lanes 4 and 5, JAK2V617F E-CFCs at passages I and IV. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; MW, molecular weight marker (50 base pair); GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Discussion

The pathophysiologic mechanisms linking JAK2V617Fmutation and the risk of thrombosis in patients with Ph-negative MPNs remain largely speculative. This study explored the hypothesis that the oncogenic lesion could hit a common endothelial and hematopoietic progenitor cell, inducing an endothelial cell dysfunction primarily responsible for the pathogenesis of the vascular damage. Either among healthy persons or patients with MPN, endothelial progenitor cells are detectable through cell culture assay only in a part of subjects, and we are not aware of biologic causes underlying this finding. Overall, our observations suggest that the ability to give rise to endothelial progenitor colonies does not identify a particular subset of patients with MPN having different hematologic or clinical peculiarities. Moreover, we show in this study that endothelial progenitor colonies isolated from patients with MPN display different profiles in respect to disease-specific molecular markers.

In general population, the reduced number of circulating endothelial progenitor cells predicts future cardiovascular events,18,26 and it is has been hypothesized that also in patients with PV this mechanism could account for the increased thrombotic risk.4 The first finding of our study is that patients with PV and ET have a level of true circulating endothelial progenitors in the normal range, whereas patients with PMF have an increased number of E-CFCs. Our data well agree with those reported in another study using the same rigorous cell culture procedures.6 Dissimilar results have been reported by other groups, but the discrepancy can be explained by the use of different culture time and conditions, which evaluated hematopoietic-derived endothelial-like colonies (ie, CFU-ECs) rather than the true endothelial ones (E-CFCs).4,7 Accordingly, we found that in our series of patients, and in particular in those patients with history of thrombosis, the CFU-EC level was significantly lower than in healthy subjects. In addition, the increased level of E-CFCs found in patients with PMF appears to be an interesting finding, considering that a defective stem cell niche would take part in the pathogenesis of this disease.27 Actually, the development of the pathologic clone in PMF is deeply influenced by alterations of the microenvironmental niches; thus, the imbalance between endosteum and vascular niches within the bone marrow could favor proliferation of hematopoietic, mesenchymal, and endothelial progenitors and their mobilization through the blood.27

The second finding of this study is that, in a subset of patients with MPN, molecular alterations usually observed in hematopoietic cells may be detected also in the circulating endothelial progenitors. Several groups investigated the relationship between endothelial cells and hematologic neoplasms,27-32 but the search for clonal markers in endothelial cells isolated from patients with Ph-negative MPN produced different and conflicting results. On the one hand, Piaggio et al6 firmly excluded that E-CFCs obtained from patients with chronic myeloproliferative diseases (including patients with chronic myeloid leukemia) harbored the disease-specific molecular clonality marker (JAK2V617F mutation or BCR-ABL rearrangement). On the other hand, Sozer et al8 not only reported the presence of JAK2V617F mutation in the liver endothelial cells of patients with BCS but also demonstrated that CD34+ cells isolated from peripheral blood of patients with JAK2V617F PV or PMF are capable of generating both wild-type and JAK2-mutated endothelial-like cells when transplanted into nonobese diabetic/ severe combined immunodeficient mice. In addition, Yoder et al7 reported that a minority of E-CFCs derived from a patient with vascular thrombosis and subsequently developing JAK2V617F PV, carried the JAK2V617F mutation. Finally, several studies established that hemangioblasts are present in chronic myeloid leukemia and contribute to both malignant hematopoiesis and endotheliopoiesis.28,33

In this study the pathologic involvement of endothelial progenitor compartment was explored by evaluating additional molecular markers of disease other than JAK2 or MPL mutations, such as clonality and hypermethylation of SOCS genes. We demonstrated that in patients with MPN a part of molecular signatures found in hematopoietic cells (both granulocytes and CFU-EC colonies) can be detected also in endothelial progenitors. Indeed, our observations add evidence to the existence of a common hematopoietic and endothelial bi-lineage progenitor also in Ph-negative MPNs. The third finding of this study is that patients with molecular abnormalities in E-CFCs need antiproliferative therapy more frequently and earlier than others. Actually, a significantly shorter antiproliferative therapy–free survival was observed in patients with JAK2V617F-positive E-CFCs.

Finally, we found that the detection of clonality and JAK2 mutation in E-CFCs was associated with a thrombotic proficiency. Interestingly, these patients have at diagnosis high JAK2 allele burden and high leukocyte count, 2 characteristics that have been associated with an increased thrombotic risk.34 Actually, the increased number of neutrophils has emerged as one of the most relevant factors contributing to the thrombophilic state of patients with MPN, and neutrophil activation occurs in these patients in parallel with the appearance of laboratory signs of hemostatic system activation.34 Moreover, the presence of high JAK2-mutated allele burden has been variably associated with both thrombosis and high leukocyte count.34 Our study supports the hypothesis that the pathogenesis of thrombosis in MPN may result from an endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction, as well. In fact, we show that the JAK2 mutation in endothelial cells abnormally activates the JAK/STAT pathway, which is an important regulator of the response of endothelial cells to injury35,36 and increases their proficiency to adhere to normal mononuclear cells. Interestingly, 2 of the 3 patients exhibiting clonal and mutated E-CFCs had thrombosis in the splanchnic veins (1 portal thrombosis and 1 BCS), whereas a third patient presenting with massive bleeding from gastric varices had severe portal hypertension, albeit in the absence of evident previous portal or suprahepatic vein thrombosis. Indeed, these findings well agree with previous observations that JAK2-mutated endothelial cells could be isolated from the liver of patients with BCS.8,9

In conclusion, this study suggests that endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction might sustain the thrombophilic state observed in patients with MPN and unravels an additional mechanism by which antiproliferative therapies could reduce the thrombotic risk. The main limit of this study resides in its retrospective nature, and only prospective investigations may definitely confirm our observations. Nevertheless, the definition of molecular profile of endothelial progenitors appears to be an attracting topic, because it could represent a useful tool for evaluating the individual thrombotic risk in each patient with MPN.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from Fondazione Roma “Progetto cellule staminali. Una nuova frontiera nella ricerca biomedica” and by PRIN 2008, Ministero Università e Ricerca Scientifica (Rome, Italy).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: L. Teofili and M.M. designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; M.G.I. and E.R.N. carried out cell cultures and analyzed data; L. Torti enrolled patients and recorded clinical data of patients; S.C. and T.C. performed molecular analysis; and L.M.L. and G.L. designed the study and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Luigi M. Larocca, Istituto di Anatomia Patologica, Università Cattolica, Largo Gemelli 8, 00168 Roma, Italy; e-mail: llarocca@rm.unicatt.it

References

Author notes

L. Teofili and M.M. contributed equally to the study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal