Abstract

After the discovery of NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in 2005 and its subsequent inclusion as a provisional entity in the 2008 World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms, several controversial issues remained to be clarified. It was unclear whether the NPM1 mutation was a primary genetic lesion and whether additional chromosomal aberrations and multilineage dysplasia had any impact on the biologic and prognostic features of NPM1-mutated AML. Moreover, it was uncertain how to classify AML patients who were double-mutated for NPM1 and CEBPA. Recent studies have shown that: (1) the NPM1 mutant perturbs hemopoiesis in experimental models; (2) leukemic stem cells from NPM1-mutated AML patients carry the mutation; and (3) the NPM1 mutation is usually mutually exclusive of biallelic CEPBA mutations. Moreover, the biologic and clinical features of NPM1-mutated AML do not seem to be significantly influenced by concomitant chromosomal aberrations or multilineage dysplasia. Altogether, these pieces of evidence point to NPM1-mutated AML as a founder genetic event that defines a distinct leukemia entity accounting for approximately one-third of all AML.

Introduction

The remarkable molecular heterogeneity of acute myeloid leukemia (AML)1 has made a genetic-based classification essential for accurate diagnosis, prognostic stratification, monitoring minimal residual disease, and developing targeted therapies. The category of “AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities,” which includes the genetically best defined myeloid neoplasms, underwent major changes in the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) classification.2 The 4 molecularly distinct entities that had been described in the 2001 WHO classification were expanded to include AML with t(6;9), AML with inv(3) or t(3;3), and AML (megakaryoblastic) with; t(1;22) and 2 provisional entities: AML with mutated CEBPA and AML with mutated nucleophosmin (NPM1) (Table 1). The latter accounts for approximately one-third of all AMLs3 and has distinct genetic, pathologic, immunophenotypic, and clinical characteristics.4,5 The WHO synonym for AML with mutated NPM1, NPMc+ AML (c+ indicates “cytoplasmic positive”),3 focuses on its most distinguishing functional feature, that is, aberrant expression of nucleophosmin in the cytoplasm of leukemic cells.6 This unique immunohistochemical pattern, which led in 2005 to the discovery of NPM1 mutations in AML,3 is an excellent surrogate marker for molecular studies because it is fully predictive of NPM1 mutations.7,8

WHO classifications of “AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities”

| WHO 2001 . | WHO 2008 . |

|---|---|

| AML with t(8;21)(q22;q22), (AML1/ETO) | AML with t(8;21)(q22;q22); RUNX1-RUNX1T1 |

| AML with inv(16)(p13q22) or t(16;16)(p13;q22), (CBFβ/MYH11) | AML with inv(16)(p13.1q22) or t(16;16)(p13.1;q22); CBFβ/MYH11 |

| Acute promyelocytic leukemia AML with t(15;17)(q22;q12), (PML/RARα) and variants | Acute promyelocytic leukemia AML with t(15;17)(q22;q12); PML/RARα* |

| AML with 11q23 (MLL) abnormalities | AML with t(9;11)(p22;q23); MLLT3-MLL† |

| AML with t(6;9)(p23;q34); DEK-NUP214 | |

| AML with inv(3)(q21;q26.2) or t(3;3) (q21;q26.2); RPN1-EVI1 | |

| AML (megakaryoblastic) with t(1;22)(p13;q13); RBM15-MKL1 | |

| AML with mutated NPM1 (provisional entity)‡ | |

| AML with mutated CEBPA (provisional entity)‡ |

| WHO 2001 . | WHO 2008 . |

|---|---|

| AML with t(8;21)(q22;q22), (AML1/ETO) | AML with t(8;21)(q22;q22); RUNX1-RUNX1T1 |

| AML with inv(16)(p13q22) or t(16;16)(p13;q22), (CBFβ/MYH11) | AML with inv(16)(p13.1q22) or t(16;16)(p13.1;q22); CBFβ/MYH11 |

| Acute promyelocytic leukemia AML with t(15;17)(q22;q12), (PML/RARα) and variants | Acute promyelocytic leukemia AML with t(15;17)(q22;q12); PML/RARα* |

| AML with 11q23 (MLL) abnormalities | AML with t(9;11)(p22;q23); MLLT3-MLL† |

| AML with t(6;9)(p23;q34); DEK-NUP214 | |

| AML with inv(3)(q21;q26.2) or t(3;3) (q21;q26.2); RPN1-EVI1 | |

| AML (megakaryoblastic) with t(1;22)(p13;q13); RBM15-MKL1 | |

| AML with mutated NPM1 (provisional entity)‡ | |

| AML with mutated CEBPA (provisional entity)‡ |

The rare variant translocations of RARα with partner genes other than PML are recognized separately because they may exhibit atypical APL features, including resistance to all-trans-retinoic acid therapy.

Compared with the 2001 WHO scheme, the category of AML with MLL gene abnormalities of 2008 WHO classification only includes AML with MLLT3-MLL. Rearrangements of MLLT3-MLL should be specified in the diagnosis. Partial tandem duplication of MLL should not be placed in this category.

Defined as “provisional” to indicate that more study is needed to characterize and establish them as unique entities.

The present review is an update of the distinct genetic and clinical features of AML with mutated NPM1.

AML with mutated NPM1 shows distinct genetic features

Several pieces of evidence suggest the NPM1 mutation is a founder genetic alteration (Table 2) in AML.

Distinctive features of AML with mutated NPM1 (NPMc+ AML)

| Genetic features |

| NPM1 mutation* is specific for AML, mostly “de novo” |

| Usually all leukemic cells carry the NPM1 mutation |

| Mutually exclusive with other “AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities” |

| NPM1 mutation is stable (consistently retained at relapse) |

| NPM1 mutation usually precedes other associated mutations (eg, FLT3-ITD) |

| Unique GEP signature (↓ CD34 gene; ↑ HOX genes) |

| Distinct microRNA profile |

| Clinical, pathologic, immunophenotypic, and cytogenetic features |

| Common in adult AML (∼ 30% of cases), less frequent in children (6.5%-8.4%)† |

| Higher incidence in female‡ |

| Close association with normal karyotype (∼ 85% of cases) |

| ∼ 15% of cases carry chromosome aberrations, especially +8, del9(q), +4 |

| Wide morphologic spectrum (more often M4 and M5) |

| Frequent multilineage involvement |

| Negativity for CD34 (90%-95% of cases)§ |

| Good response to induction therapy |

| Relatively good prognosis (in the absence of FLT3-ITD) |

| Genetic features |

| NPM1 mutation* is specific for AML, mostly “de novo” |

| Usually all leukemic cells carry the NPM1 mutation |

| Mutually exclusive with other “AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities” |

| NPM1 mutation is stable (consistently retained at relapse) |

| NPM1 mutation usually precedes other associated mutations (eg, FLT3-ITD) |

| Unique GEP signature (↓ CD34 gene; ↑ HOX genes) |

| Distinct microRNA profile |

| Clinical, pathologic, immunophenotypic, and cytogenetic features |

| Common in adult AML (∼ 30% of cases), less frequent in children (6.5%-8.4%)† |

| Higher incidence in female‡ |

| Close association with normal karyotype (∼ 85% of cases) |

| ∼ 15% of cases carry chromosome aberrations, especially +8, del9(q), +4 |

| Wide morphologic spectrum (more often M4 and M5) |

| Frequent multilineage involvement |

| Negativity for CD34 (90%-95% of cases)§ |

| Good response to induction therapy |

| Relatively good prognosis (in the absence of FLT3-ITD) |

GEP indicates gene expression profiling.

Or its immunohistologic surrogate (cytoplasmic NPM, NPMc+).

Lower incidence in Chinese children.

In most, but not all, studies.

Less than 10% CD34+ cells.

With the exception of rare cases of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/myeloproliferative neoplasms9 that require further confirmation, the NPM1 mutation or its immunohistochemical surrogate (cytoplasmic nucleophosmin) appears to be restricted to AML3,10 and is usually expressed in the whole leukemic population. It has a recurrence rate of approximately 30% in AML and is mutually exclusive of other AML recurrent genetic abnormalities.3,11 As expected for a founder genetic lesion, the NPM1 mutation is stable over the course of disease.12,13 Notably, it has been detected in AML at relapse, even many years after the initial diagnosis,14 in patients experiencing more than one relapse and in relapses occurring in extramedullary sites.15 Although loss of NPM1 mutation has been sporadically observed in NPM1-mutated AML,16 no extensive investigations were performed to exclude secondary, clonally unrelated, AML.17 Because many groups currently use NPM1 mutation as a tool to evaluate minimal residual disease, further data on the stability of NPM1 mutations should be soon available. Finally, when AML with mutated NPM1 carries a concomitant FLT3-ITD (∼ 40% of cases),3 the NPM1 mutation appears to precede FLT3-ITD.18,19

As expected for a founder genetic lesion, the NPM1 mutation defines a subgroup of AML with a distinct gene expression profile (including down-regulation of CD34 and up-regulation of HOX genes)20-22 and microRNA signature22-24 (including up-regulation of miR-10a and miR-10b). Sequencing of the whole genome from 2 cases of AML with normal karyotype (AML-NK) at 91%25 and 98% resolution,26 respectively, did not reveal any recurrent lesion, other than the NPM1 mutation, which showed features of a primary genetic hit. Indeed, in one case,25 the NPM1 and FLT3 genes were involved, whereas the other patient26 harbored a mutated NPM1 gene and concomitant NRAS and IDH1 gene mutations. Mutations of FLT3 and NRAS in AML are widely recognized as secondary genetic events, which are associated with tumor progression. The impact of IDH1 mutation26,27 on the molecular pathogenesis of AML remains to be elucidated. Interestingly, one NPM1-mutated/IDH1-mutated AML patient was recently reported to have lost IDH1 mutation at relapse while retaining the NPM1 mutation, suggesting that at least in this case IDH1 mutation was probably a secondary event.28 Studies of additional genomes from AML patients with normal karyotype are warranted to clarify the pathogenetic role of NPM1 mutation and its relationship with other mutations.

Overall, the features of NPM1-mutated AML appear to overlap with those of well-recognized primary AML genetic lesions, such as the AML1-ETO fusion gene (Table 3). Similar characteristics are also shown by AML carrying double CEBPA mutations, but not by AML-NK associated with other mutations (Table 3), because the latter are probably secondary genetic events. As an example, FLT3-ITD and FLT3-TKD are less stable than NPM1 mutation, being lost at relapse in approximately 9% and 50% of cases, respectively.29,30 Instability has been also reported for NRAS31 and WT132 mutations. Consequently, if recurrence and the other distinctive features shown in Tables 2 and 3 are to be considered the main criteria for judging the relevance of an individual genetic alteration for pathogenesis, the NPM1 mutation appears the most probable candidate as the primary, driving genetic lesion in approximately 60% of AML-NK. This view is further supported by recent evidence showing the NPM1 mutant perturbs hemopoiesis in experimental models and is expressed in the leukemic stem cells from patients with NPM1-mutated AML (discussed in the next 2 sections).

Features of mutations most frequently associated with AML carrying a normal karyotype (AML-NK) compared with a primary genetic lesion [t(8;21)]

| Feature . | Primary genetic event in AML* [eg, t(8;21)] . | NPM1 . | CEBPA . | FLT3 ITD . | FLT3 TKD . | NRAS . | WT1 . | MLL-PTD . | IDH1 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrence | Yes | 50%-60% | 5%-10% | 30% | 10%-15% | 10%-12% | 7%-10% | 5%-10% | ∼ 15% |

| Distinct GEP | Yes | Yes | Yes‡ | No | No | NA | Yes | No | No |

| Distinct microRNA profile | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | NA | NA | No |

| Specificity for AML | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes§ | Yes§ | No | No | Yes | No |

| Mutually exclusive† | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes‖ |

| Timing of the event | Early | Early | Early | Usually late¶ | Usually late¶ | Usually late | NA | Early | NA |

| % mutated cells within the leukemic population | All | All | All | It may occur in a subclone | It may occur in a subclone | It may occur in a subclone | NA | All | All |

| Loss at relapse | No | No | No | Possible | Possible | Possible | Possible | No | Rarely28 |

| Feature . | Primary genetic event in AML* [eg, t(8;21)] . | NPM1 . | CEBPA . | FLT3 ITD . | FLT3 TKD . | NRAS . | WT1 . | MLL-PTD . | IDH1 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrence | Yes | 50%-60% | 5%-10% | 30% | 10%-15% | 10%-12% | 7%-10% | 5%-10% | ∼ 15% |

| Distinct GEP | Yes | Yes | Yes‡ | No | No | NA | Yes | No | No |

| Distinct microRNA profile | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | NA | NA | No |

| Specificity for AML | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes§ | Yes§ | No | No | Yes | No |

| Mutually exclusive† | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes‖ |

| Timing of the event | Early | Early | Early | Usually late¶ | Usually late¶ | Usually late | NA | Early | NA |

| % mutated cells within the leukemic population | All | All | All | It may occur in a subclone | It may occur in a subclone | It may occur in a subclone | NA | All | All |

| Loss at relapse | No | No | No | Possible | Possible | Possible | Possible | No | Rarely28 |

GEP indicates gene expression profiling; and NA, not available data.

Refers to typical features of an “AML with recurrent genetic abnormality” (WHO 2008) that is used for comparison.

With other recurrent genetic abnormalities.

Refers to biallelic CEBPA-mutated cases.

Rarely occurs in ALL.

Occasionally seen in AML carrying recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities and complex karyotype.

In NPM1/FLT3-ITD double-mutated cases, NPM1 mutation appears to precede FLT3-ITD.

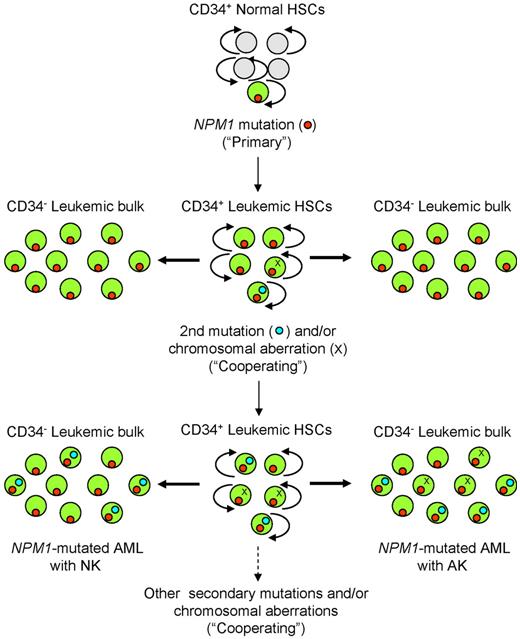

Besides the primary genetic event, secondary cooperating mutations are thought to play a major role in leukemogenesis.33 Recurrent genetic lesions that probably cooperate with the NPM1 mutation include chromosomal aberrations (in ∼ 15% of cases)3 and mutations, such as those affecting the FLT3-ITD, FLT3-D835, NRAS, IDH1, and TET2 genes (in ∼ 60% of cases). Hypothetical steps of leukemic transformation in NPM1-mutated AML are shown in Figure 1.

Hypothetical steps of genetic evolution in NPM1-mutated AML. In this scheme, the CD34+ hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) compartment (whether normal or leukemic) is shown in the central column, whereas its more differentiated CD34-negative progeny is shown in the right and left columns. The primary, driving NPM1 mutation (red dot) in an HSC causes transformation that leads to the “leukemic phenotype.” Other mutations (light blue dots), such as FLT3-ITD, occur later in clonal evolution. Leukemic cells in approximately 15% of NPM1-mutated AML can also acquire a chromosomal abnormality (X), whereas in 85% of cases they maintain a normal karyotype. Both later mutations and chromosomal abnormalities are usually expressed in a leukemic cell subclone whose size may vary from one patient to another. For simplicity, occurrence of the second mutation and a chromosomal abnormality in the same cells is not shown. According to the 2-hit hypothesis, only 2 mutations are indicated, but additional mutations may be involved. Light gray circles represent normal HSC and multipotent progenitors; and green circles indicate the CD34+ normal hemopoietic progenitor compartment where primary NPM1 mutation (red dot) and secondary mutations (blue dot) and/or chromosomal aberrations (X) occur, giving rise to the CD34− leukemic bulk population.

Hypothetical steps of genetic evolution in NPM1-mutated AML. In this scheme, the CD34+ hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) compartment (whether normal or leukemic) is shown in the central column, whereas its more differentiated CD34-negative progeny is shown in the right and left columns. The primary, driving NPM1 mutation (red dot) in an HSC causes transformation that leads to the “leukemic phenotype.” Other mutations (light blue dots), such as FLT3-ITD, occur later in clonal evolution. Leukemic cells in approximately 15% of NPM1-mutated AML can also acquire a chromosomal abnormality (X), whereas in 85% of cases they maintain a normal karyotype. Both later mutations and chromosomal abnormalities are usually expressed in a leukemic cell subclone whose size may vary from one patient to another. For simplicity, occurrence of the second mutation and a chromosomal abnormality in the same cells is not shown. According to the 2-hit hypothesis, only 2 mutations are indicated, but additional mutations may be involved. Light gray circles represent normal HSC and multipotent progenitors; and green circles indicate the CD34+ normal hemopoietic progenitor compartment where primary NPM1 mutation (red dot) and secondary mutations (blue dot) and/or chromosomal aberrations (X) occur, giving rise to the CD34− leukemic bulk population.

How does mutated NPM1 protein promote leukemia?

The NPM1 gene encodes for a protein that, although nucleolar at steady state,6 shuttles between nucleus and cytoplasm.34 Acting as a molecular chaperone to establish multiple protein-protein interactions, NPM1 is involved in critical cell functions,35 such as control of ribosome formation and export, stabilization of the oncosuppressor p14Arf protein in the nucleolus, and regulation of centrosome duplication. Although the NPM1 gene was strongly implicated in cancer pathogenesis,35 how the NPM1 mutant protein promotes leukemia remains elusive. Because the NPM1 mutation always results in aberrant cytoplasmic dislocation of the mutant protein,36,37 this event appears critical for leukemogenesis.6,38 Increased nucleophosmin export into cytoplasm probably perturbs multiple cellular pathways by “loss of function” (NPM1 nucleolar interactors are delocalized by the mutant into leukemic cell cytoplasm) and/or “gain of function” (the hypershuttling NPM1 mutant works in a deregulated fashion). Moreover, the NPM1 mutant could have neomorphic features (eg, capability to interact with new protein partners in the cytoplasm).4,6

NPM1 mutant-mediated cytoplasmic delocalization of nuclear proteins6 was implicated in knocking-down the oncosuppressor Arf39,40 and activating the c-MYC oncogene.41 In addition, the function of wild-type nucleophosmin in NPM1-mutated AML cells is profoundly affected by its reduction at the nucleolar physiologic site. Reduction of wild-type NPM1 in the nucleolus is the result of both heterozygosity and dislocation into cytoplasm through forming heterodimers with NPM1 mutant.6 In the Npm knockout mouse, Npm inactivation led to genomic instability which, in turn, promoted in vitro and in vivo cancer susceptibility. Npm heterozygous cells were more susceptible to oncogenic transformation and Npm+/− mice developed spontaneous tumors, especially myeloid malignancies,42 indicating how NPM1 acts as haploinsufficient tumor suppressor in vivo.

The NPM1 mutant may also exert its transforming properties through gain of function in cytoplasm. Interestingly, the NPM1 mutant bound and inhibited caspase 6 and 8 signaling in leukemic cell cytoplasm.43 In the future, functional alterations of other NPM1 interactors are expected to be identified in NPM1-mutated AML.

In vitro studies demonstrated the NPM1 mutant promoted oncogenic transformation of primary cells in cooperation with oncogenic E1A.44 In vivo, the NPM1 mutant impacted directly on myelopoiesis, favoring myeloid proliferation in transgenic mice45 and in a zebrafish embryonic model.46 In the transgenic mouse model, the most frequent human NPM1 mutation (type A) was driven by the myeloid-specific human MRP8 promoter. NPMc+ transgenic mice developed a nonreactive myeloproliferation with mature GR-1+, Mac-1+ cells accumulating in bone marrow and spleen.45 In zebrafish, ubiquitous mutant NPM1 not only caused expansion of primitive myeloid cells but also resulted in increased numbers of definitive erythro-myeloid progenitors (gata1+/lmo2bright) and hematopoietic stem cells (c-myb+/cd41+) in the aorta ventral wall (Figure 2).

NPM1 mutant in zebrafish model. In zebrafish, where mutant NPM1 was expressed ubiquitously, not only did it cause expansion of primitive myeloid cells but it also resulted in increased numbers of both definitive erythromyeloid progenitors (gata1+/lmo2bright) and hematopoietic stem cells (c-myb+/cd41+) in the ventral wall of the aorta.

NPM1 mutant in zebrafish model. In zebrafish, where mutant NPM1 was expressed ubiquitously, not only did it cause expansion of primitive myeloid cells but it also resulted in increased numbers of both definitive erythromyeloid progenitors (gata1+/lmo2bright) and hematopoietic stem cells (c-myb+/cd41+) in the ventral wall of the aorta.

However, in none of these models was the NPM1 mutant alone able to initiate AML. In the mouse model, the inability of enhanced myeloproliferation to progress to spontaneous overt AML may have been determined by either the cell type expressing NPMc+ or by low-level mutant expression in hemopoietic cell cytoplasm, which does not reproduce the features of human NPM1-mutated AML exactly. In the zebrafish embryo, follow-up for AML development was not possible because of the transient nature of mutant NPM1 expression. Consequently, to exert its oncogenic effect, NPM1 may need to act under different conditions, such as targeting a specific myeloid precursor and/or achieving a mutant to wild-type expression ratio that is appropriate for cytoplasmic delocalization of both nucleophosmin forms6,38 and/or being accompanied by a secondary cooperating event.44 Knockin mice models mimicking human NPM1-mutated AML more closely are needed to address these issues.

Origin of NPM1-mutated AML

Consistent CD34 negativity in the great majority of NPM1-mutated AML cases3 raises the question of whether a minimal pool of CD34+/CD38−NPM1-mutated progenitors exists. In NPM1-mutated AML, we and other investigators47,48 found that the small fraction of CD34+ hemopoietic progenitors, including CD34+/CD38− cells, carried the NPM1 mutation. When transplanted into immunocompromised mice, CD34+ cells generated a leukemia that recapitulated the patient's original disease, morphologically and immunohistochemically (aberrant cytoplasmic NPM1 and CD34 negativity).47

The engraftment potential of the CD34− fraction in NPM1-mutated AML appears more controversial. In one study,47 no or limited engraftment was observed in NOG mice. In contrast, Taussig et al48 reported a more consistent engraftment of the CD34− leukemic cells in immunocompromised mice. These findings may reflect some degree of heterogeneity in the leukemic stem cell compartment of NPM1-mutated AML.

Despite CD34 negativity, HOX genes, which are involved in stem cell maintenance, are consistently up-regulated in NPM1-mutated AML.20-22 However, it remains to be elucidated whether leukemic stem cells in NPM1-mutated AML originate from very early progenitors or from committed myeloid precursors, with subsequent reactivation of stem cell self-renewal machinery through HOX gene reprogramming.

Relationships between AML with mutated NPM1 and other myeloid neoplasms

“Other AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities”

AML with mutated NPM1 is mutually exclusive with other entities listed in the category of “AML with other recurrent genetic abnormalities” according to WHO-2008 (Table 1). Rare AML patients have been reported to carry the NPM1 mutation and recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities.18,21 These cases remain controversial because it is unclear whether the genetic alterations occurred in the same, or in different, leukemic cell populations.11 The significance of the rare association of NPM1 and CEBPA gene mutations in AML is discussed in “AML with mutated NPM1: new insights into controversial issues of the 2008 WHO classification.”

AML with MD-related changes

The 2008 WHO classification did not recognize a clear demarcation between NPM1-mutated AML and AML with myelodysplasia (MD)–related changes. Recent findings suggest they may be 2 distinct entities (this issue is discussed in detail in “AML with mutated NPM1: new insights into controversial issues of the 2008 WHO classification”).

Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms

Approximately 10% of therapy-related AML are NPM1-mutated.49 However it is still unclear whether therapy-related AML with mutated NPM1 is a treatment-induced secondary leukemia (such as occurs with other AML-carrying recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities) or a de novo NPM1-mutated AML in patients with a history of therapy.50

AML not otherwise specified

This is the least characterized myeloid neoplasm(s) in the 2008 WHO classification. Other entities, including AML with mutated NPM1, can be clearly differentiated through their distinctive molecular (when present), morphologic, immunophenotypic, and clinical features.

Myeloid sarcoma

Like other myeloid neoplasms associated with specific recurrent genetic abnormalities, AML with mutated NPM1 can present as isolated myeloid sarcoma, show concomitant bone marrow and extramedullary involvement, or relapse in extramedullary organs. Skin and lymph nodes are most frequently affected, even though all anatomic sites can be involved.51 In a large retrospective study in paraffin-embedded samples, approximately 15% of myeloid sarcoma carried cytoplasmic mutated nucleophosmin at immunohistochemistry.52 As expected, these cases showed overlapping features with NPM1-mutated AML, including CD34 negativity and no clinical history of previous myelodysplastic or myeloproliferative neoplasm indicating blastic transformation or evolution.52

Myeloid proliferations related to Down syndrome

We had the opportunity to investigate 2 cases of this rare neoplasm and did not find cytoplasmic NPM1 at immunohistochemistry (B.F., unpublished results, December 2009).

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm

NPM1-mutated AML and blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm may sometimes present with similar clinical and pathologic features, including skin involvement and expression of the macrophage-restricted CD68 molecule (monoclonal antibody PG-M1). Recent immunohistochemical findings clearly indicate they are separate disease entities,53 as NPM1-mutated AML consistently shows nucleophosmin expression in the cytoplasm, whereas blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm is characterized by nucleus-restricted nucleophosmin positivity (predictive of NPM1 gene in germline configuration).53

Diagnosis of NPM1-mutated AML: the strength of flexibility

One important prerequisite for a disease being included as an entity in the WHO classification is that it can be easily recognized worldwide, according to well-established and reproducible criteria. Fortunately, several molecular assays and surrogate methods are currently available for diagnosing AML with mutated NPM154 (Figure 3).

Molecular and alternative methods for diagnosis of NPM1-mutated AML. AML with mutated NPM1 can be diagnosed either by mutational analysis or by alternative methods based on detection of aberrant cytoplasmic expression of nucleophosmin (immunohistochemistry on tissue sections or flow cytometry) or the mutant NPM1 protein with specific antibodies (Western blotting). The 2 approaches are complementary (bidirectional arrows). Evaluation of the FLT3 status should be carried out in all NPM1-mutated AML patients because it is instrumental to identify the subgroup of cases with NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITD-negative genotype that has a more favorable prognosis. Primers can be designed that allow monitoring of minimal residual disease (MRD).

Molecular and alternative methods for diagnosis of NPM1-mutated AML. AML with mutated NPM1 can be diagnosed either by mutational analysis or by alternative methods based on detection of aberrant cytoplasmic expression of nucleophosmin (immunohistochemistry on tissue sections or flow cytometry) or the mutant NPM1 protein with specific antibodies (Western blotting). The 2 approaches are complementary (bidirectional arrows). Evaluation of the FLT3 status should be carried out in all NPM1-mutated AML patients because it is instrumental to identify the subgroup of cases with NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITD-negative genotype that has a more favorable prognosis. Primers can be designed that allow monitoring of minimal residual disease (MRD).

Molecular analysis

Highly specific and sensitive molecular assays are available for detecting NPM1 mutations.55 One of the most frequently used at diagnosis is fragment analysis (genescan analysis),18 which has the advantage of multiplexing with FLT3-specific or CEBPA-specific assays.56 It does not, however, discriminate type A NPM1 mutation from rare variants, and all samples that are positive at fragment analysis have to be sequenced for detailed characterization. On the other hand, melting curve assays, which include mutation-specific probes, are not only useful in screening but also discriminate between type A, B, and D mutations,57 and sequencing is required only for 5% of patients with rare mutation types. These methods at diagnosis show a sensitivity of approximately 5%.

More sensitive methods have to be applied to detect minimal residual disease, and the mutation sequence at diagnosis needs to be known. The most sensitive are quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays with mutation specific primers, which can be applied on DNA58 as well as on RNA.57,58 RNA-based quantitative real-time PCR is able to detect 1:100 000 cells. Another alternative is latent nuclear antigen-mediated PCR clamping, which is rapid and has a sensitivity of 1:100 to 1:1000.59 Although usually carried out on RNA or DNA extracted from peripheral blood or bone marrow leukemic blasts,55,60 paraffin-embedded samples52 and plasma61 are also suitable for analysis.

Approximately 50 molecular variants of NPM1 mutations have been identified so far.62 They are almost always at exon 12 but have occasionally been found in other exons.37 NPM1 mutations are detected in approximately one-third of adult AML (50%-60% of all AML with normal cytogenetics)3,4 but only in 6.5% to 8.4% of pediatric AML63-65 ; they were absent in children younger than 3 years.64 Type A NPM1 mutation (4 base TCTG insertion) is the most frequent in adults (75%-80% of cases), whereas NPM1 mutations other than type A predominate in children.66

Detection of cytoplasmic nucleophosmin: a surrogate for molecular analysis

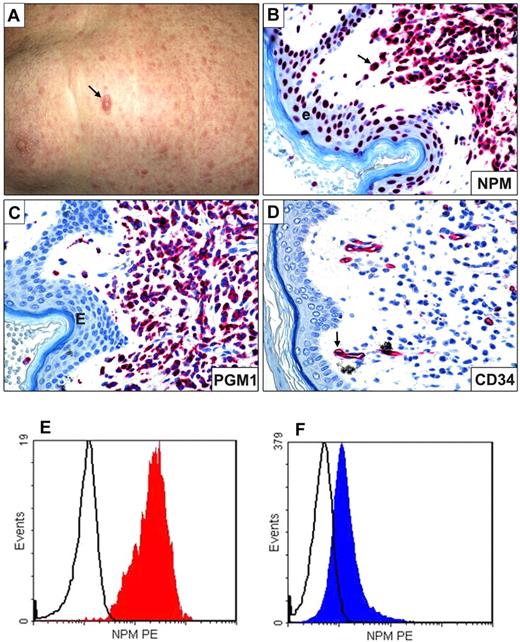

One of the WHO's primary goals is the widespread use of the genetic-based AML classification. As molecular techniques are not always available for diagnosis, especially in developing countries, there is great interest in suitable substitutes. Morphology and immunophenotype (frequent CD34 negativity) cannot be used because NPM1-mutated AML encompasses various French-American-British categories, and the absence of CD34 is also observed in other AML genetic subtypes. Appearing to fill the gap for AML with mutated NPM1 is a simple, low-cost, and highly specific immunohistochemical assay, which predicts NPM1 mutations by looking at ectopic nucleophosmin expression in the cytoplasm of leukemic cells7,8 in bone marrow and in extramedullary sites (myeloid sarcomas; Figure 4). This approach successfully assessed multilineage involvement in bone marrow samples from patients68 and tracked engraftment of CD34+NPM1-mutated AML cells in immunocompromised mice.47 Detection of cytoplasmic NPM as surrogate for molecular diagnosis of NPM1-mutated AML is reminiscent of identifying acute promyelocytic leukemia with t(15;17) or ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphomas, by, respectively, anti-PML (PG-M3)69 and anti-ALK monoclonal antibodies.70

Myeloid sarcoma expressing cytoplasmic NPM1 and flow cytometric detection of cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in AML. (A) Multiple skin lesions; the arrow indicates the largest lesion. (B) Leukemic cells infiltrating the derma show aberrant cytoplasmic expression of NPM (arrow); the cells of epidermis (e) exhibit the expected nucleus-restricted positivity for NPM. (C) Leukemic cells express the histiocyte-restricted form of CD68 (monoclonal antibody PG-M1). (D) Leukemic cells are CD34−; the arrow indicates a CD34+ vessel that serves as internal control. (B-D) Alkaline phosphatase antialkaline phosphatase technique; hematoxylin counterstaining; images were collected using an Olympus B61 microscope and a UPlan FI 100×/1.3 NA oil objective; Camedia 4040, Dp_soft Version 3.2; and Adobe Photoshop 7.0. (E) Flow cytometry analysis of cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in AML. NPM1-mutated AML M5b 48% blasts showing the phenotype: CD34−CD13+CD33+CD117+MPO− CD56+NPMc+. (F) AML M1 with wild-type NPM1 gene and 93% blasts with phenotype: CD34+ CD13+ CD33+ CD117+ MPO+CD56+NPMc− (bottom left and right; courtesy of Prof Christian Thiede and Dr U. Oelschlaegel, University of Dresden, Dresden, Germany).

Myeloid sarcoma expressing cytoplasmic NPM1 and flow cytometric detection of cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in AML. (A) Multiple skin lesions; the arrow indicates the largest lesion. (B) Leukemic cells infiltrating the derma show aberrant cytoplasmic expression of NPM (arrow); the cells of epidermis (e) exhibit the expected nucleus-restricted positivity for NPM. (C) Leukemic cells express the histiocyte-restricted form of CD68 (monoclonal antibody PG-M1). (D) Leukemic cells are CD34−; the arrow indicates a CD34+ vessel that serves as internal control. (B-D) Alkaline phosphatase antialkaline phosphatase technique; hematoxylin counterstaining; images were collected using an Olympus B61 microscope and a UPlan FI 100×/1.3 NA oil objective; Camedia 4040, Dp_soft Version 3.2; and Adobe Photoshop 7.0. (E) Flow cytometry analysis of cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in AML. NPM1-mutated AML M5b 48% blasts showing the phenotype: CD34−CD13+CD33+CD117+MPO− CD56+NPMc+. (F) AML M1 with wild-type NPM1 gene and 93% blasts with phenotype: CD34+ CD13+ CD33+ CD117+ MPO+CD56+NPMc− (bottom left and right; courtesy of Prof Christian Thiede and Dr U. Oelschlaegel, University of Dresden, Dresden, Germany).

Questions arise about which samples, techniques, and type of anti-NPM antibodies should be used. Aberrant cytoplasmic expression of nucleophosmin is optimally detected in paraffin sections from B5-fixed/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-decalcified bone marrow trephines.7,8 Less reliable results were reported in bone marrow biopsies fixed in formalin and decalcified in formic acid.71 Preliminary findings from our laboratory suggest discrepancies may result from the decalcifying agent (formic acid) rather than to formalin fixation (B.F., unpublished results, February 2010). Expression of cytoplasmic NPM was difficult to assess by immunocytochemistry in smears,72 probably because of artifact diffusion among cell compartments and even outside leukemic cells.54 More recently, flow cytometry was successfully used to detect nucleophosmin accumulation in leukemic cell cytoplasm73,74 (Figure 4). This assay could serve as a complementary or even as an alternative procedure to bone marrow biopsy immunohistochemistry, allowing rapid measurement of cytoplasmic NPM1 and correlations with other markers in routine immunophenotyping.

Which antibodies should be used to visualize subcellular expression of nucleophosmin? Some anti-NPM antibodies recognize both wild-type and mutated NPM1,3 whereas others identify only the NPM1 mutant.68,74 Immunohistochemistry as first line screening for NPM1-mutated AML is best achieved using the former because they detect all NPM1 mutated proteins, including those generated by the very rare NPM1 mutations occurring in exons other than 12. In contrast, reagents that are specific for NPM1 mutant A74 fail to identify some mutants and may be more suitable for flow cytometric monitoring of minimal residual disease.

Prognostic features of NPM1-mutated AML

AML with mutated NPM1 is highly responsive to induction chemotherapy.3,4 Approximately 80% of patients achieve complete remission with clearance of leukemic cells as early as 16 days after starting treatment.75 The exquisite chemosensitivity of NPM1-mutated AML is probably related to the aberrant dislocation of nucleophosmin from nucleolus to cytoplasm, but the underlying mechanism through which this occurs remains unknown.

The prognostic significance of NPM1 mutations was mainly investigated in AML with normal karyotype. In patients younger than 60 years, the outcome is similar to the “good-risk” AML categories carrying t(8;21) or inv(16),64,76 unless a concomitant FLT3-ITD mutation is present.18,21,57,76,77 This is hardly surprising as FLT3-ITD impacts negatively on the prognosis of other AML genetic subtypes, including AML with mutated CEBPA.78 Similarly, the good prognosis of AML with t(8;21)/RUNX1/RUNX1T1-positive is worsened by the presence of concomitant Kit-D816 mutations.79 As a certain number of patients succumb to their disease, even in the prognostically favorable subgroup of NPM1-mutated AML without FLT3-ITD, other, as yet unidentified, secondary genetic lesions may cooperate with NPM1 to induce leukemia and influence prognosis. NPM1 mutations are frequently associated with IDH1 mutations, which were recently identified by whole genome sequencing.26 Some investigators reported that, when concomitant, IDH1 mutations may adversely impact the favorable prognosis associated with NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITD-negative genotype,27,80 leading to the suggestion that IDH1 mutation analysis might serve to refine prognostic stratification in NPM1-mutated AML cases without FLT3-ITD.27,80 However, these findings were not confirmed in other studies28,81 where the unfavorable effect on prognosis of IDH1 mutation was mainly found in AML patients with the unmutated NPM1 genotype.

Although the prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations was largely demonstrated for AML patients younger than 60 years, several studies included elderly patients57 who were recently investigated in depth. In patients older than 60 years, Büchner et al82 found a 52.1% incidence of NPM1-mutated AML-NK compared with 66.4% in patients younger than 60 years (P = .0189). The favorable constellation of mutant NPM1 and normal FLT3 status was found at comparable frequencies (36.5% and 33.2%) in younger and older patients, equally predicting better survival and longer duration of remission in multivariate analyses. In 909 AML patients who were older than 60 years, Röllig et al83 revealed that karyotype, age, NPM1 mutation status, white blood cell count, lactate dehydrogenase, and CD34 expression were independent prognostic markers for overall survival. The authors defined a novel prognostic model and found that NPM1 mutation status significantly influenced overall survival, whereas FLT3-ITD status did not. Finally, in AML-NK patients 70 years of age or older, Becker et al22 found that, at multivariate analysis, the NPM1 mutation was the only factor influencing prognosis. Overall survival was approximately 40% if an NPM1 mutation was present but only 5% in cases carrying an unmutated NPM1 gene.22 Taken together, these findings support the value of NPM1 mutation as a molecular tool for selecting elderly patients for whom aggressive chemotherapy is worth adopting.

As for any type of AML that has attained complete remission, the question is whether the patient should undergo an allogeneic stem cell transplantation, which is so far the most effective treatment modality for AML. Because of its intrinsic risk of morbidity and mortality, this procedure is generally reserved for young AML patients carrying high-risk genetic abnormalities. In contrast, AML patients with relatively good prognosis, such as those carrying t(15;17), t(8;21), or inv(16), are usually not transplanted in first complete remission.1 This policy was also proposed for AML with mutated NPM1 in the absence of concurrent FLT3-ITD because no apparent benefit seems to derive from allogeneic transplantation in these patients76 who account for approximately 16% of all newly diagnosed de novo AML younger than 60 years.1 These cases are currently treated with conventional therapy, with or without autologous stem cell transplantation. Further prospective studies are warranted to confirm these findings.

AML with mutated NPM1: new insights into controversial issues of the 2008 WHO classification

In the 2008 WHO classification, NPM1-mutated AML was listed as a provisional entity because uncertainties persisted about the biologic significance and prognostic impact of additional chromosomal aberrations and multilineage dysplasia in AML with mutated NPM1 and how AML patients who were double-mutated for NPM1 and CEBPA should be classified. Recent studies provided insights into these areas.

What is the biologic and clinical significance of chromosomal aberrations in AML with mutated NPM1?

Approximately 15% of AML with mutated NPM1 harbor chromosomal aberrations other than typical recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities.3 The significance of these chromosomal abnormalities was recently addressed in 631 AML patients with mutated/cytoplasmic NPM1.84 Chromosomal aberrations were found in 14.7%, with the most frequent anomalies being +8, +4, −Y, del(9q), and +2184 (Table 4). Several findings suggested these chromosomal aberrations were secondary events.84 Although less frequent, they were mostly similar to additional chromosome aberrations that are widely regarded as secondary events in AML with t(8;21), inv(16), t(15;17), or 11q23/MLL-rearrangements.84 They were often subclones within the leukemic population with normal karyotype3 (mosaicism). More importantly, 4 of 31 NPM1-mutated AML patients with NK at diagnosis remained NPM1-mutated while switching to the following abnormal karyotype at relapse: del(9q) (n = 2), t(2;11) (n = 1), and inv(12) (n = 1).84 In addition, few NPM1-mutated AML with abnormal karyotype at diagnosis showed either clonal regression (change from abnormal to normal karyotype) or switched to a different abnormal karyotype at relapse, while retaining the original NPM1-mutated gene status.84 NPM1-mutated AML with normal or abnormal karyotype showed the same gene expression profile and immunophenotype.84 Finally, in 2 independent clinical trials, the karyotype did not appear to impact on the favorable prognosis (overall and event-free survival) of NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITD-negative AML patients.84 However, another study observed that an abnormal karyotype had a negative impact on event-free survival of NPM1-mutated AML.85 The discrepancy may be the result of the small number of patients analyzed by Micol et al85 and/or differences in therapy or type of chromosomal aberrations.

Clonal chromosome abnormalities detected in NPM1-mutated AML and other AML with recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities

| Karyotype . | AML . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPM1 mutation (n = 689) . | t(8;21) (n = 100) . | inv(16) (n = 73) . | t(15;17) (n = 147) . | 11q23/MLL (n = 79) . | |

| Additional abnormalities | 105/689 (15.2%) | 71/100 (71.0%) | 24/73 (32.9%) | 61/147 (41.5%) | 37/80 (46.2%) |

| −X/−Y | 18 | 48 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| +4 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| −7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| +8 | 43 | 5 | 11 | 21 | 15 |

| +13 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| +19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| +21 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| +22 | 1 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 2 |

| del(7q) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| del(9q) | 9 | 17 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| del(11q) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ider(17)(q10)t(15;17) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Other | 67 | 15 | 9 | 48 | 40 |

| Karyotype . | AML . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPM1 mutation (n = 689) . | t(8;21) (n = 100) . | inv(16) (n = 73) . | t(15;17) (n = 147) . | 11q23/MLL (n = 79) . | |

| Additional abnormalities | 105/689 (15.2%) | 71/100 (71.0%) | 24/73 (32.9%) | 61/147 (41.5%) | 37/80 (46.2%) |

| −X/−Y | 18 | 48 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| +4 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| −7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| +8 | 43 | 5 | 11 | 21 | 15 |

| +13 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| +19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| +21 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| +22 | 1 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 2 |

| del(7q) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| del(9q) | 9 | 17 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| del(11q) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ider(17)(q10)t(15;17) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Other | 67 | 15 | 9 | 48 | 40 |

This table is an update of the findings reported by Haferlach et al.84

The major problem with these studies is that, because of the rarity of chromosomal aberrations in NPM1-mutated AML, their prognostic significance has been difficult to assess and has been based on all abnormal karyotypes being grouped together. However, as single abnormalities, they may have distinctly different outcomes. Large meta-analysis studies should help to further clarify this issue.

What is the biologic and clinical significance of myelodysplasia-related changes in AML with mutated NPM1?

According to the new WHO classification,86 a case is diagnosed as AML with MD-related changes, in the presence of one or more of the following: (1) previous, well-documented, history of MDS or MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasm; (2) myelodysplasia-related cytogenetic abnormalities; and (3) multilineage dysplasia (ie, detection of dysplasia in 50% or more of cells in 2 or more myeloid lineages in bone marrow and/or peripheral blood smears). When the 2008 WHO classification was being prepared, the significance of an NPM1 mutation in the setting of morphologic dysplasia in an AML patient with NK was still unclear.87 Thus, the new WHO classification presently recommends that cases with overlapping features should be diagnosed as “AML with MD-related changes,” additionally annotating the presence of NPM1 mutation.86

A large study on 318 AML patients with mutated NPM188 provided definitive evidence that multilineage dysplasia, detected in approximately 23% of cases (Figure 5), has no impact on gene expression profile or pathologic, immunophenotypic, clinical, and prognostic features of NPM1-mutated AML. These findings indicate that presence of an NPM1 mutation should predominate over multilineage dysplasia as disease-defining criterion. This is in line with lack of biologic and clinical significance of multilineage dysplasia in other AML genetic subtypes.89

Multilineage dysplasia in NPM1-mutated AML. (A) Dysgranulopoiesis (Dys G) in a case of NPM1-mutated AML showing myeloid cells with hypogranulated cytoplasm and pseudo-Pelger cells. Bone marrow, Pappenheim staining. (B) Dyserythropoiesis (Dys E) in a case of NPM1-mutated AML showing nuclear irregularity with fragmentation, a mitosis, and multinucleation of red precursors. Bone marrow, Pappenheim staining. (C) Dysmegakaryopoiesis (Dys M) in a case of NPM1-mutated AML showing 2 dysplastic megakaryocytes with multiple nuclei. Bone marrow, Pappenheim staining. (A-C) All images were collected using a Zeiss Axio Imager.A1, 63×/1.4 oil objective Plan-Apochromat; 10×/23 eyepiece Sony camera 3CCD HD, Model MC-HD 1/3 Horn imaging DHS solution. (D) Lightcycler-based melting curve analyses showing different NPM1 mutation types in AML with MLD changes: A (nt959insTCTG), D (nt959insCCTG), I (nt959insCTTG), X (nt959insTTCC), and wild-type patients. (E-F) Expression of CD34 by multiparameter flow cytometry. A case with NPM1 mutation and MLD changes demonstrating a lack of expression of CD34 (E, note the different levels of CD33 expression between myeloblasts and monoblasts). A different AML MLD+ case without NPM1 mutation showing a strong expression of CD34 with a part of the population lacking CD33 expression (F). Slightly modified from Falini et al88 with permission.

Multilineage dysplasia in NPM1-mutated AML. (A) Dysgranulopoiesis (Dys G) in a case of NPM1-mutated AML showing myeloid cells with hypogranulated cytoplasm and pseudo-Pelger cells. Bone marrow, Pappenheim staining. (B) Dyserythropoiesis (Dys E) in a case of NPM1-mutated AML showing nuclear irregularity with fragmentation, a mitosis, and multinucleation of red precursors. Bone marrow, Pappenheim staining. (C) Dysmegakaryopoiesis (Dys M) in a case of NPM1-mutated AML showing 2 dysplastic megakaryocytes with multiple nuclei. Bone marrow, Pappenheim staining. (A-C) All images were collected using a Zeiss Axio Imager.A1, 63×/1.4 oil objective Plan-Apochromat; 10×/23 eyepiece Sony camera 3CCD HD, Model MC-HD 1/3 Horn imaging DHS solution. (D) Lightcycler-based melting curve analyses showing different NPM1 mutation types in AML with MLD changes: A (nt959insTCTG), D (nt959insCCTG), I (nt959insCTTG), X (nt959insTTCC), and wild-type patients. (E-F) Expression of CD34 by multiparameter flow cytometry. A case with NPM1 mutation and MLD changes demonstrating a lack of expression of CD34 (E, note the different levels of CD33 expression between myeloblasts and monoblasts). A different AML MLD+ case without NPM1 mutation showing a strong expression of CD34 with a part of the population lacking CD33 expression (F). Slightly modified from Falini et al88 with permission.

NPM1-mutated AML also differs from AML with MD-related changes as it does not usually evolve from previous MDS or MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasm3 and shows distinctive features that seem to be independent of whether the karyotype is normal or abnormal,84 further supporting the view that these 2 leukemias are distinct entities (Table 5).

Differences between AML with MD-related changes and AML with mutated NPM1

| Feature . | AML with MD-related changes . | AML with mutated NPM1 . |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleophosmin | Nuclear (unmutated) | Cytoplasmic (mutated) |

| WBC count | Often severe pancytopenia | Usually high WBC count |

| Previous history of MDS or MDS/MPN | Frequent | Usually absent |

| Karyotype | Usually abnormal | Usually normal (85%) |

| CD34 | Usually positive | Usually negative |

| Prognosis | Usually poor | Favorable (if FLT3-ITD absent) |

| Feature . | AML with MD-related changes . | AML with mutated NPM1 . |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleophosmin | Nuclear (unmutated) | Cytoplasmic (mutated) |

| WBC count | Often severe pancytopenia | Usually high WBC count |

| Previous history of MDS or MDS/MPN | Frequent | Usually absent |

| Karyotype | Usually abnormal | Usually normal (85%) |

| CD34 | Usually positive | Usually negative |

| Prognosis | Usually poor | Favorable (if FLT3-ITD absent) |

WBC indicates white blood cell.

What is the significance of rare AML cases carrying both NPM1 and CEBPA mutations?

A minority (∼ 4%) of NPM1-mutated AML also carry a CEBPA mutation.90 At the time of preparation of 2008 WHO classification, this fact was thought to be difficult to reconcile with the claim that NPM1 and CEBPA mutations defined distinct AML entities. In-depth analysis of NPM1/CEBPA double-mutated cases has clarified the issue, showing that this rare association occurs only between NPM1 and monoallelic CEBPA mutations. In contrast, NPM1 mutations are usually mutually exclusive of biallelic CEBPA mutations.91 This observation is relevant for the genetic classification of these tumors because only CEBPA double mutations appear to define a genetic entity, in accordance with their distinct gene expression profile (down-regulation of HOX genes) and favorable prognosis.90,92-94

Future perspectives

Recent findings point to “AML with mutated NPM1” and “AML with biallelic CEBPA mutations” as distinct leukemia entities. Additional information is expected to accumulate over the next few years that will further help to assess whether they should be incorporated as such in the next revision of the WHO classification. Because NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITD-negative AML patients seem to have good prognosis, independently of normal or abnormal karyotype,84 one critical issue requiring clarification will be how to best risk-stratify AML patients according to molecular criteria. The current assessment of the prognostic values of NPM1, CEBPA, and FLT3-ITD mutations in the framework of normal karyotype.18,21,57 has 2 major limitations: (1) it excludes AML patients in whom cytogenetic analysis fails; and (2) it prevents AML patients from being assigned to the group with favorable genotype (eg, NPM1 mutated/FLT3-ITD-negative), if a chromosomal aberration is present. Use of “normal karyotype” as initial framework for risk stratification may be more appropriate for AML patients without NPM1 or biallelic CEBPA mutations. In this subgroup, which includes approximately 40% of AML with normal karyotype, increasing application of whole genome sequencing is expected to unravel novel causal mutations that may serve as new diagnostic and prognostic markers.

An important area of investigation in NPM1-mutated AML is the use of quantitative PCR techniques to monitor minimal residual disease, by looking at the number of NPM1 mutant copies58 at different intervals after therapy.95 Indeed, NPM1 mutations appear particularly suited to this purpose as they are a more specific, sensitive, and stable molecular marker than WT196 or FLT3-ITD.12 Recent findings suggested minimal residual disease assessment is predictive of early relapse and long-term survival.17,97 Assessment of NPM1 mutant copies at 2 different checkpoints (after double induction therapy and completion of consolidation therapy) had a similar significant impact on prognosis.98

Recent findings on NPM1-mutated AML may also strengthen efforts to design therapeutic interventions focused on the underlying genetic lesion. The observation from Schlenk et al99 that patients with NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITD-negative AML may benefit from adding ATRA to chemotherapy goes in this direction. However, these results were not confirmed in the MRC trial conducted by Burnett et al,100 and further studies are required to clarify the issue. In the future, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms through which the NPM1 mutant induces leukemia will hopefully translate into development of new effective antileukemic drugs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Susanne Schnittger for reviewing the section on molecular analysis of NPM1 mutations and Claudia Tibidò for her excellent secretarial assistance and Dr Geraldine Anne Boyd for her help in editing this paper.

The authors apologize to those whose papers could not be cited because of space limitations.

This work was supported by the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Perugia, and Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Spoleto.

Authorship

Contribution: B.F. had the original idea and wrote the manuscript; M.P.M. was responsible for biochemical studies and characterization of leukemic stem cell in NPM1-mutated AML; N.B. studied the mechanisms of transport of NPM1 mutant protein and the zebrafish model; P.S. described the transgenic mouse model; A.L. produced the specific antibody for NPM1 mutant protein and analyzed multilineage involvement in NPM1-mutated AML; E.T. performed gene expression profiling studies and immunohistochemical analyses; T.H. was involved in the clinical studies on the role of aberrant karyotype and myelodysplasia-related changes in NPM1-mutated AML; and all authors contributed to write the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.F. applied for a patent on clinical use of NPM1 mutants. T.H. is part owner of the Munich Leukemia Laboratory. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Brunangelo Falini, Institute of Hematology, University of Perugia, Ospedale S. Maria della Misericordia, S. Andrea delle Fratte, 06132 Perugia, Italy; e-mail: faliniem@unipg.it.