In this issue of Blood, Klinke et al demonstrate the ability of myeloperoxidase (MPO) to attract neutrophils to the vascular wall, a process that might contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and other inflammatory vascular disorders.

Over a hundred years ago, Julius Cohnheim used intravital microscopy to observe that leukocytes are attracted to the vascular wall at sites of inflammation.1 Over the subsequent century, there was much speculation about what mediated this attraction. Notably, electrostatic forces were suggested as one factor capable of promoting leukocyte adhesion in the vasculature.2,3 Now of course, we know about the myriad of adhesion molecules, chemokines, and chemoattractants which mediate interactions of leukocytes with the vascular wall, and how these molecules cooperate to overcome the shear forces of flowing blood which oppose leukocyte interactions.4 But is there a role for electrostatic attraction? In this issue, Klinke et al demonstrate that the highly cationic MPO molecule is able to attract leukocytes via its electrostatic characteristics.5

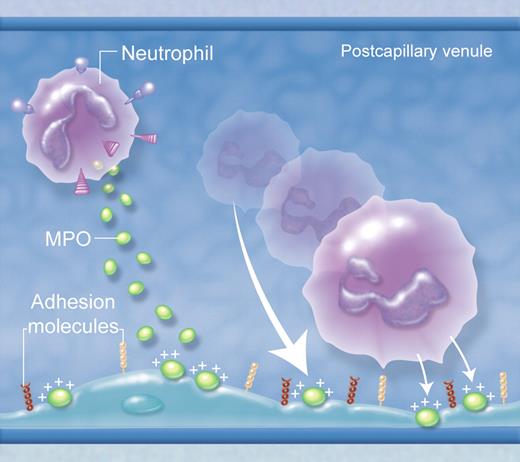

In various forms of vascular pathology, MPO is deposited in the vasculature after its release from neutrophils, binding to negatively charged glycosaminoglycans on the endothelial surface. Due to its strong positive charge, deposited MPO can attract leukocytes to the endothelial surface. However, this does not happen wherever MPO is deposited in the vasculature, but only in sites where leukocyte rolling and adhesion normally occur, such as postcapillary venules. This indicates that the attractive force of MPO is insufficient to initiate adhesion, but can augment adhesion mediated by conventional adhesion molecule pathways. (Professional illustration by Alice Chen.)

In various forms of vascular pathology, MPO is deposited in the vasculature after its release from neutrophils, binding to negatively charged glycosaminoglycans on the endothelial surface. Due to its strong positive charge, deposited MPO can attract leukocytes to the endothelial surface. However, this does not happen wherever MPO is deposited in the vasculature, but only in sites where leukocyte rolling and adhesion normally occur, such as postcapillary venules. This indicates that the attractive force of MPO is insufficient to initiate adhesion, but can augment adhesion mediated by conventional adhesion molecule pathways. (Professional illustration by Alice Chen.)

MPO is a heme-containing peroxidase highly expressed by polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Its major function is generation of hypochlorous acid as part of the neutrophil's antimicrobial armory. However, MPO ejected from neutrophils during degranulation can be deposited in the vasculature during inflammatory responses. Under these conditions, it is believed to be responsible for injury to vascular cells, via its capacity to generate damaging oxidants. Klinke et al demonstrate that the proinflammatory actions of MPO may extend to promotion of leukocyte recruitment.5 MPO is shown to invoke directional neutrophil movement in in vitro chemotaxis experiments, independent of its enzymatic activity and intracellular processes in neutrophils such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity and actin polymerization. Most interestingly, even fixed/dead neutrophils were attracted toward MPO, as were negatively charged beads. However, if the charge of the highly cationic MPO was neutralized biochemically, neutrophils were no longer attracted toward it, supporting the concept that this was a passive attraction mediated by the strong positive charge of MPO. This result might have remained an interesting quirk of an in vitro assay, but the authors also showed that MPO-deficient mice had reduced neutrophil infiltration in inflamed tissues. More importantly, after infusion of MPO into the circulation and its subsequent deposition in the vasculature, neutrophil adhesion occurred in otherwise uninflamed blood vessels where MPO was present (see figure).

These findings indicate that electrostatic forces stemming from MPO may draw leukocytes toward the vessel wall without a requirement for active cell migration, identifying a novel form of neutrophil “attraction” which may be an additional mechanism for leukocyte recruitment in inflammation. However, this result does not mean that MPO alone is sufficient for recruitment. Notably, even when MPO was administered systemically and deposited widely throughout the vasculature, leukocyte recruitment was restricted to vessels that normally support leukocyte recruitment, that is, postcapillary venules and hepatic sinusoids. This suggests that adhesion molecule–mediated interactions are necessary, presumably at least to initiate attachment of neutrophils to the endothelial surface, but that locally deposited MPO is capable of augmenting these interactions.

This work identifies an additional process which can facilitate binding of neutrophils to the endothelial surface, and their entry into inflamed sites. In diseases where cell-free MPO has been found to be deposited within the vasculature—including atherosclerosis, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion, sepsis, and forms of autoimmune glomerulonephritis—MPO may be not only directly injurious to cells in the area, but may also promote recruitment of additional neutrophils to further aggravate local damage.6-9 It remains to be seen whether this “magnetic attraction” offers up a new potential therapeutic target in inflammatory vascular disease.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal