Abstract

Recent studies have shown that factor VIIa (FVIIa) binds to the endothelial cell protein C receptor (EPCR), a cellular receptor for protein C and activated protein C, but the physiologic significance of this interaction is unclear. In the present study, we show that FVIIa, upon binding to EPCR on endothelial cells, activates endogenous protease activated receptor-1 (PAR1) and induces PAR1-mediated p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation. Pretreatment of endothelial cells with FVIIa protected against thrombin-induced barrier disruption. This FVIIa-induced, barrier-protective effect was EPCR dependent and did not involve PAR2. Pretreatment of confluent endothelial monolayers with FVIIa before thrombin reduced the development of thrombin-induced transcellular actin stress fibers, cellular contractions, and paracellular gap formation. FVIIa-induced p44/42 MAPK activation and the barrier-protective effect are mediated via Rac1 activation. Consistent with in vitro findings, in vivo studies using mice showed that administration of FVIIa before lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treatment attenuated LPS-induced vascular leakage in the lung and kidney. Overall, our present data provide evidence that FVIIa bound to EPCR on endothelial cells activates PAR1-mediated cell signaling and provides a barrier-protective effect. These findings are novel and of great clinical significance, because FVIIa is used clinically for the prevention of bleeding in hemophilia and other bleeding disorders.

Introduction

Recent studies from our laboratory1,2 and others3,4 have shown that factor VIIa (FVIIa), a clotting protease that binds to tissue factor (TF) and initiates the activation of the coagulation cascade, also binds to the endothelial cell protein C receptor (EPCR), a receptor for anticoagulant protein C/activated protein C (APC). EPCR controls coagulation by promoting the activation of protein C by thrombin-thrombomodulin complexes.5 In addition to controlling coagulation, EPCR has been shown to modulate several nonhemostatic functions by supporting APC-induced protease activated receptor-1 (PAR1)–mediated cell signaling.6-13

Although direct evidence for an association of FVIIa with EPCR in vivo is yet to come, several recent observations are a strong indication that FVIIa does in fact interact with EPCR in vivo. Both human and murine FVIIa administered to mice were shown to associate with endothelium, and blockade of EPCR with EPCR-specific antibodies was shown to prolong the human FVIIa circulatory-half life in mice.2,14 Analysis of FVII, FVIIa, and soluble EPCR levels in a large group of healthy individuals revealed that those with the EPCR Gly variants, whose circulating levels of soluble EPCR were higher, had higher levels of circulating FVII and FVIIa, suggesting that EPCR in vivo serves as a reservoir for FVII.15,16 At present, the physiologic importance of FVIIa's interaction with EPCR is not entirely clear. Our recent studies suggest that EPCR may play a role in the clearance and/or transport of FVIIa.2 Although we are unable to find evidence for the modulation of FVIIa's coagulant activity by EPCR,1 others have shown that FVIIa binding to EPCR on endothelial cells down-regulates FVIIa's coagulant activity.4 Similarly, EPCR was shown to down-regulate FVIIa generation on endothelial cells by reducing FVII accessibility to phospholipids at the cell surface.17

Despite divergent views on the potential mechanisms by which APC binding to EPCR provides cytoprotective activity through PAR1-mediated cell signaling, it is generally believed that complex formation of APC with EPCR potentiates APC cleavage of PAR1, and that PAR1 activation is responsible for eliciting protective signaling responses.6,13,18-20 In agreement with this notion, APC was shown to cleave PAR1 on endothelial cells, and EPCR-blocking antibodies that prevent APC binding to EPCR inhibited APC cleavage of PAR1.18 In studies performed in a heterologous cell model system expressing transfected EPCR and PAR1 or PAR2 reporter constructs, we found no evidence that the FVIIa bound to EPCR was capable of cleaving either PAR1 or PAR2 or of inducing cell signaling.1 In earlier studies, APC was shown to cleave PAR1 reporter constructs expressed in endothelial cells (EA.hy926 cells), but this cleavage required high concentrations of APC (75nM or higher) and was EPCR independent.10,21 In the same studies, an APC-mediated protective effect was seen with much lower concentrations of APC, and this effect was EPCR dependent. It had been suggested that, unlike the case with PAR1-transfected cells, the colocalization of PAR1 and EPCR on the plasma membrane is required for APC to cleave PAR1 and elicit cellular responses in endothelial cells.21 Studies by Russo et al20 also showed that compartmentalization of EPCR and PAR1 in discrete membrane microdomains was critical for APC-induced, PAR1-mediated cell signaling.20,21 It is possible that the transfected EPCR and PAR1 constructs may not segregate into membrane microdomains in the same way that endogenously expressed receptors do, and therefore the transfected PAR1 may not be readily accessible for cleavage by EPCR-bound proteases. Moreover, effects of various coagulation proteases on PAR-mediated cell signaling could be complex and multifaceted, and even undetectable amounts of PAR activation may lead to robust cellular responses.22,23 Therefore, in the present study we examined critically whether FVIIa bound to EPCR on endothelial cells can cleave endogenous PAR1 and activate PAR1-mediated cell signaling.

The data presented herein show that FVIIa bound to EPCR on endothelial cells cleaves endogenous PAR1 and activates p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Exposure of endothelial cells to FVIIa was shown to protect them from thrombin-induced paracellular hyperpermeability. Consistent with in vitro findings, in vivo studies in mice showed that administration of FVIIa before lipopolysaccharide (LPS) attenuated LPS-induced vascular leakage in the lung and kidney. Our present data provide evidence that FVIIa bound to EPCR on endothelial cells activates PAR1-mediated cell signaling and provides a barrier-protective effect. These findings are novel and of great clinical significance because FVIIa is used clinically for the prevention of bleeding in hemophilia and other bleeding disorders.

Methods

Reagents

Recombinant human FVIIa was from Novo Nordisk, and recombinant APC (Xigris) was from Eli Lilly. Thrombin was purchased from either Enzyme Research Laboratories or Haematologic Technologies. The PAR1 and PAR2 agonist peptides, TFLLRN-NH2 and SLIGKV-NH2, respectively, were custom synthesized and high-performance liquid chromatography purified (Biosynthesis). Monoclonal antibodies against PAR1 (ATAP2) and PAR2 (SAM11) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Hirudin was obtained from Calbiochem/EMD Biosciences. Tick anticoagulant protein (TAP) was kindly provided by George Vlasuk (Corvas International, San Diego, CA). Polyclonal neutralizing antibodies against PAR2 were kindly provided by Wolfram Ruf (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). Mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against human EPCR (JRK-1494 blocking mAb and JRK-1500 nonblocking mAb) were prepared as described previously.5 Preparation and characterization of monospecific polyclonal antibodies against human TF were also as described previously.24 Adenoviral stocks for wild-type and dominant-negative Rho and Rac1 were obtained from Christopher Waters (University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN).

Cell culture

Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from Lonza. Monolayers of HUVECs were grown to confluence at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator in endothelial basal medium (EBM-2) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum and growth supplements (Lonza). Endothelial cell passages between 3 and 8 were used.

Silencing of EPCR, PAR1, or PAR2

HUVECs were transfected with small interfering RNA (siRNA) specific for EPCR (5′-GUG GAC GGC GAU GUU AAU UAC TT-3′), PAR1 (5′-AGA UUA GUC UCC AUC AAU-3′ and 5′-AGG CUA CUA UGC CUA CUA C-3′), or PAR2 (5′-CCU CAU AAC AUU AAA CAG GTT-3′) using siPORT Amine (Ambion). In controls, HUVECs were transfected with scrambled oligonucleotides of the above sequences. siRNA oligonucleotides were obtained from Ambion or MWG-Biotech. Briefly, when cells reached 70% confluence, they were washed once with serum-free medium, and then incubated with 200nM siRNA in siPORT Amine (3 μL of siPORT Amine in a final volume of 500 μL; Ambion) in serum-free Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen). Six hours after transfection, the medium was changed to the growth medium (EBM-2 containing 5% fetal bovine serum and growth supplements). The cells were cultured for 60-72 hours before being used in experiments. Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates confirmed a marked reduction (75%-90%) of EPCR, PAR1, or PAR2 at the protein level in cells transfected with specific siRNA. Control scrambled siRNA had no effect on expression levels of EPCR, PAR1, or PAR2.

Measurement of PAR1 and PAR2 activation

FVIIa activation of PAR1 and PAR2 was evaluated initially in HUVECs transduced to express PAR1 and PAR2 reporter constructs in which alkaline phosphatase (AP) was fused to the N-terminus of PAR1 or PAR2. Briefly, HUVECs cultured in a 12-well plate were transduced with AP-PAR1 or AP-PAR2 reporter adenoviral constructs (10 MOI [multiplicity of infectious units]/cell). Two days after infection, HUVEC monolayers expressing AP-PAR1 or PAR2 were treated with FVIIa or other enzymes. Aliquots were removed immediately after the addition of the enzyme and after a 10- or 60-minute activation period. The aliquots were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 21 000 rpm to remove any cell debris, and AP activity in the supernatant was quantified using a chemiluminescence substrate from the Clontech EscAPe SEAP detection kit.

A cell-surface enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that uses conformation-specific PAR1 mAb (ATAP2) was used to measure the activation of endogenous PAR1.18 ATAP2 was shown to bind uncleaved PAR1 and not PAR1 cleaved at the activation site.18 Briefly, HUVECs cultured in a 96-well plate were treated with control vehicle, FVIIa, or thrombin as described in “Results,” and then the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The fixed cells were incubated with ATAP2 (1 μg/mL) for 1 hour at room temperature. After removing the unbound antibody, the cells were washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% BSA and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase–coupled goat anti–mouse immunoglobulin G, followed by the horseradish peroxidase substrate tetramethylbenzidine for 30 minutes. The amount of ATAP2 bound to the cell surface was determined spectrophotometrically by measuring the absorbance at 650 nm. The reading obtained with HUVECs not exposed to agonists or treated with control vehicle was defined as 100%. Exposure of HUVECs to thrombin (10nM for 60 minutes) or omission of ATAP2 antibody in the assay decreased the absorbance reading by approximately 90%, indicating that the decrease in ATAP2 binding reflects the cleavage of PAR1.

p44/42 MAPK activation

Confluent monolayers of HUVECs were serum starved overnight and the spent medium was replaced with fresh serum-free EBM-2 medium. After stabilizing the cells for 2 hours at 37°C in a CO2 incubator, the cells were treated with a control buffer, FVIIa, or other agonists for different time intervals or for a fixed time period. At the end of the treatment period, the supernatant was removed and the cells were lysed with sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer. An equal amount of protein was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membrane, probed with phospho-specific and total p44/42 MAPK antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology), and the blot developed with chemiluminescence.

Endothelial barrier permeability in vitro assay

Endothelial cell permeability was analyzed in a dual-chamber system using Evans Blue–labeled BSA. Briefly, HUVECs were seeded (5 × 104 cells/insert) on Transwell permeable support inserts (12-mm diameter, 3.0-μm pore size; Corning). The cells were cultured for 4 days to reach full confluence. After washing the cells in PBS, 0.5 and 1.5 mL of serum-free medium was added to the upper and lower chambers, respectively. FVIIa or other agonists were added to the apical chamber, and the cells were incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. Agonist solutions were then removed and thrombin (5nM) was added to the apical chamber to induce permeability. Ten minutes later, the supernatant from the apical chamber was removed and 0.5 mL of Evans Blue dye (0.67 mg/mL) in 4% BSA in serum-rich medium was added to the apical chamber. The amount of dye diffused to the lower chamber at 10 minutes was quantified and taken as an index of paracellular permeability by measuring the absorbance at 650 nm of an aliquot removed from the lower chamber. The value observed in thrombin-treated monolayers that were not exposed to any other agonists was taken as 100%.

In limited experiments, endothelial cell permeability was also measured using measurements of transendothelial electrical resistance (TER). Briefly, HUVECs were grown to confluence in 8-well culture dish containing gold-film electrodes. TER was measured in real time using an electrical cell-substrate impedance sensing system (ECIS; Applied BioPhysics). The starting TER of confluent monolayers varied between 1500 and 1800 ohms. Wells were randomly assigned for experimental treatments and reported values were normalized using the pretreatment TER for each respective well.

F-actin staining and microscopy

Confluent HUVECs grown on glass coverslips were exposed to experimental conditions as described in “Results.” After treatment, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed for 30 minutes at 4°C in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde. The fixative was removed and the remaining formaldehyde was quenched with 0.05% glycine, pH 8.0, for 5 minutes. The fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes and blocked with 3% goat serum in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Permeabilized cells were stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin for 60 minutes at room temperature to detect F-actin. The stained cells were imaged using an LSM510 Meta Confocal System (Zeiss) equipped with an Axio Observer Z1 microscope (Zeiss).

Vascular permeability in vivo assay

C57BL/6J mice were injected with saline (100 μL) or human rFVIIa (250 μg/mice in 100 μL) intravenously via the tail vein. Two hours later, LPS (E coli O111:B4, 5 mg/kg; Sigma) was injected into mice by intraperitoneal injection. Seventeen hours and 15 minutes after LPS challenge and 45 minutes before killing the mice, 100 μL of 1% Evans Blue dye was injected intravenously via tail vein. After drawing a small aliquot of blood retroorbitally, animals were perfused from the heart with 40 mL of saline via a peristaltic pump and organs were harvested. Evans Blue dye in the tissues was extracted with formamide for 18 hours at 60°C and quantified by dual-wavelength spectrophotometric analysis at 620 and 740 nm.11 Evans Blue dye levels in plasma were measured to ensure that an equal amount of dye was injected into all animals. In some studies, FVIIa was given 10 hours after LPS challenge. All studies involving animals were conducted in accordance with the animal welfare guidelines set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and by the Department of Health and Human Services. All animal procedures were approved by the University of Texas Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee.

Results

EPCR-dependent FVIIa cleavage of PAR1 in endothelial cells

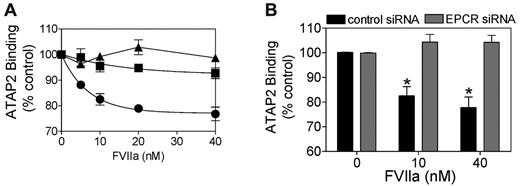

In our earlier study,1 we were unable to detect a measurable cleavage of PAR1 or PAR2 by FVIIa bound to EPCR in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected to express EPCR and PAR1 or PAR2 reporter constructs. It is possible that PAR reporter constructs and/or EPCR that were expressed in CHO cells by transfection might not have colocalized into specialized membrane microdomains such as lipid rafts and caveolae,21 and thus would be less susceptible to cleavage by FVIIa-EPCR complexes. Therefore, in the present study, we evaluated whether FVIIa can cleave endogenous PAR1 on endothelial cells that constitutively express both EPCR and PAR1. We adopted a cell-surface ELISA using ATAP2, a conformational sensitive PAR1 mAb that binds to intact but not cleaved PAR1 in the cell-surface immunoassay.18 In this assay, cleavage of PAR1 at the activation site reduced ATAP2 binding to PAR1 at the cell surface. As shown in Figure 1A and B, FVIIa reduced the binding of ATAP2 to the cell surface in a time- and dose-dependent manner, suggesting cleavage of endogenous PAR1 by FVIIa. A proteolytically inactive FVIIa (FVIIai) did not reduce ATAP2 binding to the cells (Figure 1C), indicating that the reduction in binding was mediated by the proteolytic activity of FVIIa. At a 10nM concentration of FVIIa, a concentration equivalent to the plasma concentration of FVII, the efficiency of PAR1 cleavage by FVIIa appeared to be comparable to that of APC (Figure 1C). At this concentration, FVIIa cleaved approximately 25% of PAR1 present at the cell surface in 1 hour. It was interesting that neither increasing the FVIIa concentration (up to 40nM) nor increasing the duration of the treatment period (to 2 hours) led to further cleavage of the remaining PAR1 at the cell surface. However, the addition of thrombin (1nM for 60 minutes) to FVIIa-treated cells (10nM for 1 hour) resulted in cleavage of the remaining PAR1 (data not shown). These data suggest that only a fraction of PAR1 at the cell surface is accessible to FVIIa. Traces of FXa or thrombin that might have formed in the cell system were not responsible for the observed cleavage of PAR1 in HUVECs treated with FVIIa, because specific and potent inhibitors of FXa or thrombin, 100nM TAP or 4 U/mL of hirudin, respectively, failed to diminish the FVIIa (10nM) cleavage of PAR1. Experiments conducted in parallel showed that these inhibitors were fully capable of inhibiting FXa- or thrombin-induced cleavage of PAR1 (data not shown).

FVIIa cleaves PAR1 on endothelial cells. Confluent monolayers of HUVECs were incubated at 37°C with (A) control buffer (○) or FVIIa (10nM; ●) for varying time periods, (B) varying concentrations of FVIIa for 1 hour, or (C) FVIIa (10nM), FVIIai (10nM), APC (10nM), or thrombin (1nM) for 1 hour. At the end of treatment, the supernatants were removed, the cell monolayer was fixed, and the residual intact (uncleaved) PAR1 at the cell surface was detected by cell surface ELISA using a conformation-specific PAR1 mAb (ATAP2). The spectrophotometric reading obtained for ATAP2 binding to untreated cells was taken as 100% (n = 5-7; mean ± SEM).

FVIIa cleaves PAR1 on endothelial cells. Confluent monolayers of HUVECs were incubated at 37°C with (A) control buffer (○) or FVIIa (10nM; ●) for varying time periods, (B) varying concentrations of FVIIa for 1 hour, or (C) FVIIa (10nM), FVIIai (10nM), APC (10nM), or thrombin (1nM) for 1 hour. At the end of treatment, the supernatants were removed, the cell monolayer was fixed, and the residual intact (uncleaved) PAR1 at the cell surface was detected by cell surface ELISA using a conformation-specific PAR1 mAb (ATAP2). The spectrophotometric reading obtained for ATAP2 binding to untreated cells was taken as 100% (n = 5-7; mean ± SEM).

In additional studies, FVIIa cleavage of PAR1 was found to be inhibited completely in the presence of polyclonal antibodies against EPCR (Figure 2A). Similarly, the inclusion of 100-fold molar excess of APCi along with FVIIa, which prevents FVIIa binding to EPCR by direct competition, also blocked FVIIa cleavage of PAR1 in endothelial cells (Figure 2A). The involvement of EPCR in FVIIa cleavage of endogenous PAR1 was further confirmed by EPCR silencing. FVIIa failed to cleave PAR1 in HUVECs transfected with EPCR siRNA, whereas it cleaved PAR1 in HUVECs transfected with a scrambled EPCR siRNA (Figure 2B). FVIIa cleavage of PAR1 in endothelial cells was independent of TF, because unperturbed HUVECs express very little TF and anti-TF antibodies had no effect on FVIIa cleavage of PAR1. Moreover, transduction of TF by adenoviral particles encoding TF did not increase the extent of FVIIa cleavage of PAR1 in HUVECs (data not shown).

FVIIa cleavage of PAR1 on HUVECs is dependent on EPCR. (A) HUVECs were treated with varying concentrations of FVIIa in the absence (●) or presence of polyclonal anti-EPCR antibody (50 μg/mL; ■) or APCi (1μM; ▴) for 1 hour. (B) HUVECs transfected with control scrambled siRNA (200nM, dark bar) or EPCR siRNA (200nM, gray bar) were treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 1 hour. Residual uncleaved intact PAR1 was measured in a cell-surface ELISA using ATAP2 (n = 3).

FVIIa cleavage of PAR1 on HUVECs is dependent on EPCR. (A) HUVECs were treated with varying concentrations of FVIIa in the absence (●) or presence of polyclonal anti-EPCR antibody (50 μg/mL; ■) or APCi (1μM; ▴) for 1 hour. (B) HUVECs transfected with control scrambled siRNA (200nM, dark bar) or EPCR siRNA (200nM, gray bar) were treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 1 hour. Residual uncleaved intact PAR1 was measured in a cell-surface ELISA using ATAP2 (n = 3).

We also attempted to determine whether FVIIa bound to EPCR also cleaves PAR2 in endothelial cells. However, low expression of PAR2 in HUVECs and the lack of a cleavage-specific antibody for PAR2 prevented us from obtaining any reliable information regarding this question. As observed in the earlier study with CHO-EPCR cells,1 we could not detect any significant and measurable cleavage of exogenously expressed PAR2 or PAR1 by FVIIa over the control vehicle in HUVECs transduced with AP-PAR2 or AP-PAR1 reporter constructs, respectively (data not shown).

FVIIa activation of p44/42 MAPK in endothelial cells

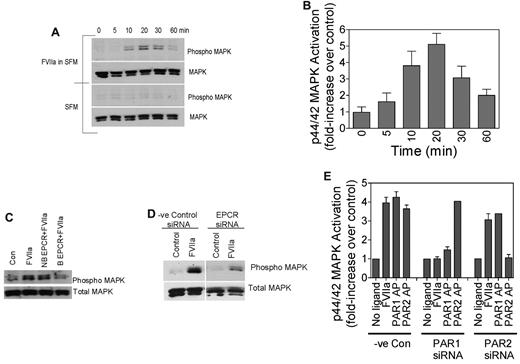

To determine whether FVIIa cleavage of PAR1 in endothelial cells mediates cell signaling, we evaluated the effect of FVIIa on p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation, because thrombin and APC activation of PAR1 have been shown to induce p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation in endothelial cells.8 As shown in Figure 3A-B, FVIIa induces p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation in endothelial cells in a time-dependent fashion. Pretreatment of HUVECs with polyclonal antibodies against EPCR or EPCR-blocking mAb inhibited FVIIa-induced p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation (Figure 3C). Treatment of HUVECs with EPCR nonblocking mAb did not prevent FVIIa-induced p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation. Consistent with these data, EPCR siRNA but not a scrambled siRNA markedly reduced FVIIa-induced p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation when transfected into HUVECs (Figure 3D). Next, we investigated whether FVIIa-induced p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation was dependent on the FVIIa activation of PAR1. PAR1 or PAR2 were silenced selectively by transfecting HUVECs with PAR1- or PAR2-specific siRNA. Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates of siRNA-transfected cells showed that PAR1 and PAR2 siRNAs selectively reduced PAR1 and PAR2 protein levels in HUVECs by more than 75%. As shown in Figure 3E, PAR1 silencing inhibited FVIIa-induced p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation, whereas PAR2 silencing had no effect on FVIIa-induced p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation. These data clearly support the hypothesis that FVIIa bound to EPCR is capable of mediating cell signaling in endothelial cells via activation of PAR1.

FVIIa activation of p44/42 MAPK in endothelial cells. (A-B) Confluent monolayers of HUVECs were treated with FVIIa (10nM) or control vehicle for varying times at 37°C. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with phospho-specific or total p44/42 MAPK antibodies. Panel A shows an immunoblot from a representative experiment and panel B shows quantified data of FVIIa-induced p44/42 MAPK activation in HUVECs (n = 4-7). (C) HUVECs were treated with a control vehicle, nonblocking (NB) EPCR mAb, or blocking (B) EPCR mAb for 30 minutes at room temperature before being treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 20 minutes. (D) HUVECs, transfected with control siRNA or EPCR siRNA, were treated with a control vehicle or FVIIa (10nM) for 20 minutes. Cell lysates were analyzed for p44/42 MAPK activation by immunoblot analysis. (E) HUVECs were transfected with control siRNA, PAR1 siRNA, or PAR2 siRNA, and the transfected cells were treated with control vehicle, FVIIa (10nM), PAR1 agonist peptide (50μM), or PAR2 agonist peptide (50μM) for 20 minutes. Cell lysates were analyzed for p44/42 MAPK activation by immunoblot analysis and the band intensities were quantified by densitometry (n = 2-5).

FVIIa activation of p44/42 MAPK in endothelial cells. (A-B) Confluent monolayers of HUVECs were treated with FVIIa (10nM) or control vehicle for varying times at 37°C. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with phospho-specific or total p44/42 MAPK antibodies. Panel A shows an immunoblot from a representative experiment and panel B shows quantified data of FVIIa-induced p44/42 MAPK activation in HUVECs (n = 4-7). (C) HUVECs were treated with a control vehicle, nonblocking (NB) EPCR mAb, or blocking (B) EPCR mAb for 30 minutes at room temperature before being treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 20 minutes. (D) HUVECs, transfected with control siRNA or EPCR siRNA, were treated with a control vehicle or FVIIa (10nM) for 20 minutes. Cell lysates were analyzed for p44/42 MAPK activation by immunoblot analysis. (E) HUVECs were transfected with control siRNA, PAR1 siRNA, or PAR2 siRNA, and the transfected cells were treated with control vehicle, FVIIa (10nM), PAR1 agonist peptide (50μM), or PAR2 agonist peptide (50μM) for 20 minutes. Cell lysates were analyzed for p44/42 MAPK activation by immunoblot analysis and the band intensities were quantified by densitometry (n = 2-5).

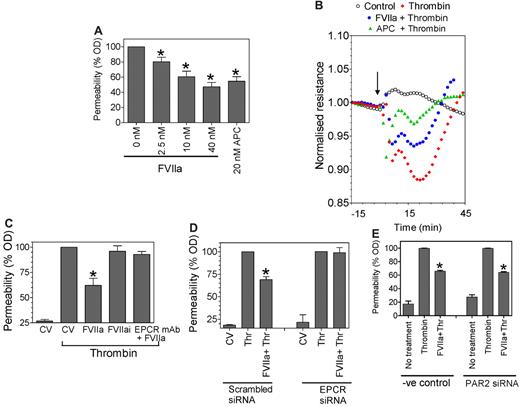

FVIIa pretreatment reduces thrombin-mediated barrier dysfunction

Earlier studies measuring albumin flux in a dual-chamber system have shown that thrombin disrupts the barrier function of endothelial cells and that pretreatment with APC reduces thrombin-induced hyperpermeability.8,21 A similar experimental approach was used here to evaluate whether FVIIa-EPCR–mediated cell signaling also attenuates thrombin-induced hyperpermeability. FVIIa pretreatment of HUVECs for 2 hours reduced thrombin-induced permeability significantly (Figure 4A). This FVIIa protective effect was dose dependent; at a concentration of 10nM, FVIIa reduced the thrombin-induced hyperpermeability by approximately 40%, a similar degree of protection observed with APC, which was used as a positive control in our experiments. The inclusion of specific inhibitors against FXa or thrombin (ie, TAP or hirudin) along with FVIIa pretreatment had no effect on the FVIIa-induced barrier-protective response, ruling out the possibility that traces of FXa or thrombin that might have formed upon addition of FVIIa were responsible for the observed protective effect. As reported recently,25 FXa pretreatment also elicited the protective response and that TAP completely attenuated this FXa-induced protective response (data not shown). The measurement of TER, a sensitive measure of barrier integrity,26 further confirmed that FVIIa pretreatment attenuates thrombin-mediated barrier disruption (Figure 4B). The FVIIa-mediated protective effect is dependent on FVIIa binding to EPCR, because inhibition of FVIIa binding to EPCR by pretreatment of HUVECs with blocking EPCR mAb (Figure 4C) or silencing EPCR by EPCR-specific siRNA (Figure 4D) abolished the FVIIa-mediated barrier-protective effect.

FVIIa pretreatment reduces thrombin-induced barrier disruption. (A) HUVECs (5 × 104 cells) were plated on 12-well Transwell chambers and cultured for 4 days. Confluent monolayers were treated with varying concentrations of FVIIa or APC (20nM) for 2 hours, and then FVIIa (or APC) was removed before the monolayers were treated with thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes. At the end of 10 minutes, thrombin was removed, the cells were washed with PBS, Evans Blue-BSA was added to the upper chamber, and the amount of dye leaked to the bottom chamber at 10 minutes was measured by measuring optical density at 650 nm. The optical density reading obtained with thrombin treatment of cells not exposed to any prior treatment was taken as 100%. *P < .05 compared with thrombin control (n = 6-10). (B) HUVECs (2 × 105 cells) were plated onto each well of an 8-well ECIS chamber slide. After 48 hours, the cells were equilibrated with serum-free medium for 1 hour and left alone (top line) or exposed to FVIIa (10nM, 3rd line from the top), APC (20nM, 2nd line from the top), or control vehicle (bottom line) for 2 hours, followed by thrombin (5nM). Uninterrupted continuous resistance was collected with the ECIS measuring apparatus from the beginning. Because there was no change in the resistance before the addition of thrombin, this portion of the readings was not included in the figure. The arrow indicates the time of thrombin addition. (C) HUVECs cultured to confluence in Transwells as described in panel A were treated with control vehicle (CV), FVIIa (10nM) ± EPCR mAb (25 μg/mL), or FVIIai (10nM) for 2 hours, and then with thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes. Cell permeability after thrombin treatment was determined by the migration of Evans Blue-BSA from the apical to the bottom chamber (n = 3-6). (D) HUVECs transfected with scrambled siRNA or EPCR-specific siRNA were treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 2 hours, followed by thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes. Permeability was measured as described in panel A. *P < .05 compared with thrombin treatment alone. (E) HUVECs transfected with scrambled siRNA or PAR2 specific siRNA were treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 2 hours, followed by thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes. Permeability was measured as described in panel A. *Statistically significant (P < .05) compared with thrombin treatment alone.

FVIIa pretreatment reduces thrombin-induced barrier disruption. (A) HUVECs (5 × 104 cells) were plated on 12-well Transwell chambers and cultured for 4 days. Confluent monolayers were treated with varying concentrations of FVIIa or APC (20nM) for 2 hours, and then FVIIa (or APC) was removed before the monolayers were treated with thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes. At the end of 10 minutes, thrombin was removed, the cells were washed with PBS, Evans Blue-BSA was added to the upper chamber, and the amount of dye leaked to the bottom chamber at 10 minutes was measured by measuring optical density at 650 nm. The optical density reading obtained with thrombin treatment of cells not exposed to any prior treatment was taken as 100%. *P < .05 compared with thrombin control (n = 6-10). (B) HUVECs (2 × 105 cells) were plated onto each well of an 8-well ECIS chamber slide. After 48 hours, the cells were equilibrated with serum-free medium for 1 hour and left alone (top line) or exposed to FVIIa (10nM, 3rd line from the top), APC (20nM, 2nd line from the top), or control vehicle (bottom line) for 2 hours, followed by thrombin (5nM). Uninterrupted continuous resistance was collected with the ECIS measuring apparatus from the beginning. Because there was no change in the resistance before the addition of thrombin, this portion of the readings was not included in the figure. The arrow indicates the time of thrombin addition. (C) HUVECs cultured to confluence in Transwells as described in panel A were treated with control vehicle (CV), FVIIa (10nM) ± EPCR mAb (25 μg/mL), or FVIIai (10nM) for 2 hours, and then with thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes. Cell permeability after thrombin treatment was determined by the migration of Evans Blue-BSA from the apical to the bottom chamber (n = 3-6). (D) HUVECs transfected with scrambled siRNA or EPCR-specific siRNA were treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 2 hours, followed by thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes. Permeability was measured as described in panel A. *P < .05 compared with thrombin treatment alone. (E) HUVECs transfected with scrambled siRNA or PAR2 specific siRNA were treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 2 hours, followed by thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes. Permeability was measured as described in panel A. *Statistically significant (P < .05) compared with thrombin treatment alone.

To investigate whether the FVIIa-mediated protective effect is dependent on potential activation of PAR2 by FVIIa bound to EPCR, HUVECs were incubated with PAR2-neutralizing antibodies before the addition of FVIIa. Blocking PAR2 with these antibodies did not abolish the FVIIa-induced protective effect (data not shown). In additional experiments, blocking PAR2 expression in HUVECs with specific PAR2 siRNA was found not to attenuate the FVIIa-induced barrier-protective effect (Figure 4E).

Effect of FVIIa on thrombin-induced cytoskeleton rearrangement

The actin cytoskeletal arrangement plays a critical role in maintaining both intracellular and intercellular adhesions and barrier function of endothelial cell monolayers.27 Therefore, we next investigated whether FVIIa pretreatment prevents thrombin-induced actin cytoskeletal rearrangement. As reported previously,26 thrombin treatment promotes formation of transcellular actin stress fibers that results in increased tension, cellular contraction, and paracellular gap formation (Figure 5). FVIIa (10nM) treatment significantly reduced these thrombin-induced effects on actin cytoskeletal rearrangement. In FVIIa-treated endothelial cells, no stress fibers were formed on exposure to thrombin, and the actin filaments remained at the cell perijunctional boundary, as noted in control cells that were not subjected to any treatment (Figure 5).

FVIIa prevents thrombin-induced cytoskeletal rearrangement. HUVEC monolayers were treated with a control vehicle (A-B) or FVIIa (10nM; C) for 2 hours, and then with thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes (B-C). The cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin to detect F-actin. Cells were imaged using a confocal system (LSM 510 META; Zeiss) equipped with an Axio Observer Z1 microscope (Zeiss).

FVIIa prevents thrombin-induced cytoskeletal rearrangement. HUVEC monolayers were treated with a control vehicle (A-B) or FVIIa (10nM; C) for 2 hours, and then with thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes (B-C). The cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin to detect F-actin. Cells were imaged using a confocal system (LSM 510 META; Zeiss) equipped with an Axio Observer Z1 microscope (Zeiss).

Role of Rho and Rac GTPases in FVIIa-induced p44/42 MAPK activation and barrier protection

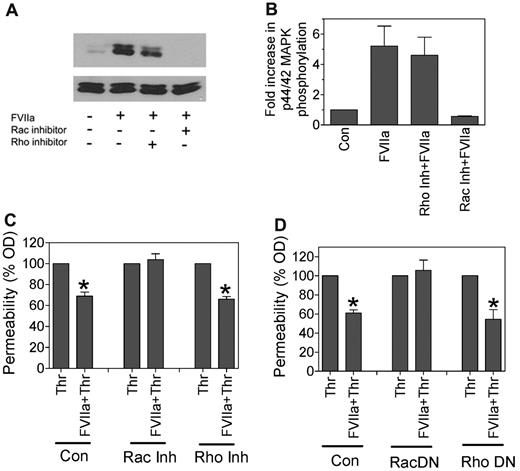

It has been shown that the Rho family of small GTPases regulates cortical actin distribution and therefore modulates barrier-disruptive or protective effects mediated by thrombin and APC, respectively.26,28,29 To determine whether the Rho family plays a role in FVIIa-induced cell signaling and the barrier-protective effect, we investigated the effect of specific inhibition of Rho or Rac1 activation on FVIIa-induced p44/42 phosphorylation and the barrier-protective effect on endothelial cells. Treatment of HUVECs with Rac1 inhibitor (NSC 23766) completely attenuated FVIIa-induced p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation in HUVECs, whereas Rho inhibitor (Y-27632) had no significant effect (Figure 6A-B). Consistent with these data, treatment of HUVECs with Rac1 inhibitor but not Rho inhibitor abolished the FVIIa-mediated barrier-protective effect (Figure 6C). In additional experiments, we evaluated the role of Rac1 and Rho activation in the FVIIa-induced barrier-protective effect by down-regulating the activation of these proteins by overexpressing dominant-negative mutant forms. As shown in Figure 6D, overexpression of the Rac1 dominant-negative mutant completely abolished the FVIIa-mediated barrier-protective effect. In contrast, overexpression of the Rho dominant-negative mutant had no significant effect on the FVIIa-induced barrier-protective effect in endothelial cells. These data suggest that FVIIa activation of Rac1 mediates the FVIIa-induced barrier-protective response.

FVIIa-induced p44/42 MAPK activation and barrier protection is mediated via Rac1. (A) HUVECs were treated with specific inhibitors of Rac1 (NSC 23766, 100μM) or RhoA (Y-27632, 10μM) for 2 hours before being treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 20 minutes. Activation of p44/42 MAPK was evaluated by immunoblot analysis. (B) Same treatment as in panel A, but p44/42 MAPK activation was quantified by densitometry (n = 3). (C) HUVECs cultured in Transwells were treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 2 hours in the absence or presence of Rac1 inhibitor (NSC 23766, 100μM) or RhoA inhibitor (Y-27632, 10μM), and then thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes to induce permeability. (D) HUVECs cultured in Transwells were infected with adenovirus (20 MOI/cell) encoding the dominant-negative variant of Rac1 (Rac DN) or RhoA (Rho DN). After culturing cells for 48 hours, confluent monolayers were treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 2 hours, and then thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes. Permeability was measured as described in Figure 4. *Statistically significant (P < .05) compared with thrombin treatment alone.

FVIIa-induced p44/42 MAPK activation and barrier protection is mediated via Rac1. (A) HUVECs were treated with specific inhibitors of Rac1 (NSC 23766, 100μM) or RhoA (Y-27632, 10μM) for 2 hours before being treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 20 minutes. Activation of p44/42 MAPK was evaluated by immunoblot analysis. (B) Same treatment as in panel A, but p44/42 MAPK activation was quantified by densitometry (n = 3). (C) HUVECs cultured in Transwells were treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 2 hours in the absence or presence of Rac1 inhibitor (NSC 23766, 100μM) or RhoA inhibitor (Y-27632, 10μM), and then thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes to induce permeability. (D) HUVECs cultured in Transwells were infected with adenovirus (20 MOI/cell) encoding the dominant-negative variant of Rac1 (Rac DN) or RhoA (Rho DN). After culturing cells for 48 hours, confluent monolayers were treated with FVIIa (10nM) for 2 hours, and then thrombin (5nM) for 10 minutes. Permeability was measured as described in Figure 4. *Statistically significant (P < .05) compared with thrombin treatment alone.

Administration of FVIIa reduces LPS-induced vascular leakage in mice

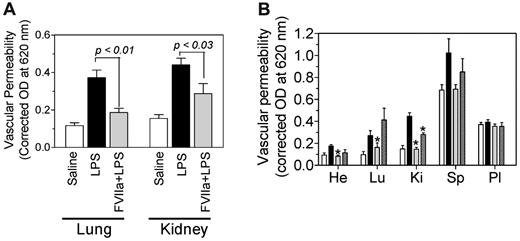

Both thrombin and LPS were shown to disrupt barrier function and promote vascular leakage through a common mechanism, S1P3 activation.11,30,31 Therefore, we have used an LPS-induced vascular leakage model to determine whether FVIIa provides a barrier-protective effect in vivo. rFVIIa (250 μg intravenously) was administered to mice 2 hours before LPS challenge (5 mg/kg intraperitoneally), and vascular leakage was assessed 18 hours after LPS challenge by injecting cell-impermeable Evans Blue to mice intravenously and measuring the leakage of dye into tissues. As expected, LPS administration markedly increased vascular leakage into the lung and kidney (Figure 7A). The administration of rFVIIa before LPS significantly reduced the vascular leakage into these tissues. In additional studies, rFVIIa was administered 10 hours after LPS challenge to determine whether FVIIa prevents the vascular leakage elicited by subsequent host-response pathways. Under this experimental condition, rFVIIa reduced vascular permeability modestly (∼ 20%-30%) in the heart, kidney, and spleen, and this modest reduction reached statistical significance in the kidney but not in the other tissues (Figure 7B). These data suggest that FVIIa provides a protective effect against vascular leakage by attenuating the direct inflammatory effects of LPS on the host response and by modulating subsequent host-response pathways.

FVIIa protects mice from increased vascular permeability in LPS challenge. (A) C57J BL (n = 11-13) mice were injected with saline (open bars) or LPS (5 mg/kg; black bars) intraperitoneally. In a third group, FVIIa (250 μg) was administered via tail vein to mice 2 hours before the LPS challenge (gray bars). (B) C57J BL mice (n = 3-5) were injected with saline, LPS, and FVIIa as described in panel A. In an additional group, FVIIa was not administered before, but instead was given 10 hours after LPS injection (hatched bars/last bar in each group). Vascular permeability in various tissues was measured 18 hours after LPS challenge by injecting 0.1 mL of 1% Evans Blue dye 45 minutes before the termination of the experiment and measuring the extravasation of dye into tissues. He indicates heart; Lu, lung; Ki, kidney; Sp, spleen; and Pl, plasma. *Statistically significant difference (P < .05) compared with mice challenged with LPS but not treated with FVIIa.

FVIIa protects mice from increased vascular permeability in LPS challenge. (A) C57J BL (n = 11-13) mice were injected with saline (open bars) or LPS (5 mg/kg; black bars) intraperitoneally. In a third group, FVIIa (250 μg) was administered via tail vein to mice 2 hours before the LPS challenge (gray bars). (B) C57J BL mice (n = 3-5) were injected with saline, LPS, and FVIIa as described in panel A. In an additional group, FVIIa was not administered before, but instead was given 10 hours after LPS injection (hatched bars/last bar in each group). Vascular permeability in various tissues was measured 18 hours after LPS challenge by injecting 0.1 mL of 1% Evans Blue dye 45 minutes before the termination of the experiment and measuring the extravasation of dye into tissues. He indicates heart; Lu, lung; Ki, kidney; Sp, spleen; and Pl, plasma. *Statistically significant difference (P < .05) compared with mice challenged with LPS but not treated with FVIIa.

Discussion

The endothelial cell lining constitutes the interface between vascular tissue and circulating blood. In their quiescent state, endothelial cells provide a nonthrombogenic surface and express receptors that participate in anticoagulant mechanism(s) such as EPCR and thrombomodulin, but are devoid of the procoagulant receptor TF. Being at the interface between blood and the vessel wall, endothelial cells are positioned optimally to interact with circulating clotting factors. Until recently, it was generally believed that FVIIa, the protease that initiates the coagulation cascade, does not interact with the endothelium because native endothelial cells do not express TF, the only known cofactor/receptor for FVII/FVIIa at the time. However, recent studies from our laboratory1,2 and others3,4 have established that FVII/FVIIa binds to EPCR on native, unperturbed endothelial cells. The discovery that FVIIa binds to EPCR, a known receptor for anticoagulant protein C/APC, in a true ligand fashion predicts novel roles for FVIIa and/or EPCR in vascular biology. Recent studies have shown that EPCR, in addition to controlling coagulation by modulating the protein C–mediated anticoagulant pathway, contributes to anti-inflammatory responses and cytoprotective effects via APC-induced PAR1-mediated cell signaling.6-9,12,21,32 Recent studies have also established that FVIIa, upon binding to TF, is capable of inducing PAR-mediated cell signaling.22,33 In the present study, we demonstrate for the first time that FVIIa interaction with EPCR on endothelial cells is also capable of activating PAR1 and, as observed with APC-EPCR, FVIIa-EPCR–induced PAR-1 activation on endothelial cells leads to protection against endothelial barrier dysfunction induced by thrombin.

In our previous studies,1 we used a heterologous expression system to determine whether FVIIa binding to EPCR can activate PAR1 or PAR2. In those studies, we found that FVIIa bound to EPCR neither cleaved PAR1/PAR2 nor activated p44/42 MAPK. Based on those data, we concluded that FVIIa bound to EPCR cannot trigger cell signaling by activating PARs. However, it has been suggested recently that colocalization of EPCR and PAR1 in lipid rafts/caveolae is required for APC to cleave PAR1 and elicit protective cellular responses in endothelial cells.20,21 AP-PAR1 reporter constructs expressed in EA.hy926 or HEK293 cells were believed to be expressed on the cell surface but not in lipid rafts.21 APC cleavage of transfected PAR1 was found to be independent of EPCR,21 whereas APC cleavage of endogenous PAR1 in endothelial cells was found to be dependent on EPCR.18 Lack of EPCR dependency21 and the requirement for relatively high concentrations of APC to cleave transfected PAR110,21 suggest that the transfected PAR1 may not colocalize with EPCR in lipid rafts, and free APC, albeit with less efficiency, could cleave PAR1. Thus, it is conceivable that EPCR and PAR1 coexpressed in CHO cells might also not have colocalized, and therefore FVIIa bound to EPCR was unable to cleave PAR1 in our earlier study.1

The possibility that transfected receptors may not segregate in the same fashion as that of endogenous receptors prompted us to determine in this study whether FVIIa bound to EPCR on endothelial cells could cleave endogenous PAR1. Our present data clearly demonstrate that FVIIa does in fact cleave endogenous PAR1 on the surface of endothelial cells, and that FVIIa cleavage of PAR1 is strictly dependent on EPCR, indicating that FVIIa bound to EPCR is responsible for the cleavage of PAR1 on endothelial cells. The limited cleavage of PAR1 by FVIIa coincides with earlier observations that PAR1 and EPCR were colocalized in lipid rafts and caveolae in endothelial cells, and that the EPCR-bound protease could only activate this subpopulation of PAR1 compartmentalized in these membrane microdomains.18,20,21 Although the present study was not aimed at comparing the efficiency of FVIIa and APC cleavage of endogenous PAR1, at the 10nM concentration, FVIIa and APC cleaved endogenous PAR1 on the endothelial cell surface to a similar extent.

As observed with APC,8 FVIIa activation of PAR1 on endothelial cells led to activation of p44/42 MAPK and inhibition of thrombin-induced barrier permeability. Although FVIIa treatment appeared to provide only a partial protective effect, this effect was substantial, consistent, and statistically significant. More importantly, it was comparable to that observed with APC in experiments conducted in parallel with FVIIa treatments. The present data suggest that EPCR-dependent barrier protection may not be unique to APC, because FVIIa, which binds to EPCR, could also initiate the EPCR-dependent protective effect. The present finding differs from a previously reported finding in which FVIIa pretreatment had no effect on thrombin-induced barrier permeability.10 The reason for this discrepancy is unknown at present, but the higher concentration of FVIIa (50nM) and/or the different endothelial cell-model system used in this earlier study (EA.hy926) might have contributed to the discrepancy. Unlike HUVECs, EA.hy926 endothelial cells express substantial amounts of TF without any perturbation, and this could confound the results.

The actin cytoskeleton plays an important role in maintaining intracellular and intercellular adhesions, as well as the barrier-regulatory properties of endothelial cell monolayers. Thrombin or other barrier-disruptive agents were shown to cause formation of transcellular actin stress fibers, which increase cellular tension, resulting in cell contraction and paracellular gap formation.26,34 Such rearrangement of the cytoskeleton was thought to be primarily responsible for decreased barrier function in confluent endothelial cell monolayers exposed to thrombin.34 The barrier-protective effect of FVIIa observed in the present study appeared to stem from preventing thrombin-induced cytoskeletal rearrangement. It had been shown previously that activation of Rac1 by various agonists provides a barrier-protective cortical cytoskeleton distribution.35-37 Recent studies have suggested that APC- but not thrombin-induced PAR1-mediated cell signaling activates Rac1 in endothelial cells, and this selective activation of Rac1 by APC is responsible for the barrier-protective effect associated with APC-EPCR.20,29 In the present study, the FVIIa-mediated barrier-protective effect was completely attenuated in HUVEC monolayers treated with Rac1 inhibitor or infected with the Rac1 dominant-negative mutant. These data suggest that the FVIIa-mediated protective effect involves the activation of Rac1 and its subsequent effect on maintaining the barrier-protective cortical distribution of the actin cytoskeleton.

There is much debate regarding how EPCR-dependent PAR1-mediated signaling provides a barrier-protective response given that thrombin-induced PAR1 signaling leads to barrier disruption in endothelial cell monolayers. Several hypotheses have been proposed, including but not limited to the following: (1) the level of receptor activation may dictate the type of response, low-level receptor activation catalyzed by EPCR bound APC invokes a protective response, whereas high-level receptor activation induced by thrombin invokes a barrier-disruptive response8,18,21 ; or (2) compartmentalization of EPCR and PAR1 in caveolae and the lipid raft facilitates selective activation of PAR1 by EPCR-bound protease in specialized membrane microdomains, which facilitates coupling of PAR1 signaling to a barrier-protective signaling pathway, and thrombin lacks this specificity.19-21 Recently, Bae et al10 showed convincingly that EPCR occupancy by protein C or a catalytically inactive mutant of protein C was sufficient to inhibit thrombin-induced barrier permeability, suggesting that EPCR occupancy by ligand protein C/APC switches PAR1-dependent signaling specificity of thrombin from a barrier-disruptive to a barrier-protective response in endothelial cell monolayers. Although it is likely that FVIIa may elicit a barrier-protective response in endothelial cells sharing 1 or more of the above-described mechanisms for APC, mere occupancy of EPCR by ligand FVIIa is not sufficient to provide a protective effect, because we found that catalytically inactive FVIIa, which binds to EPCR, fails to provide any barrier-protective response. Thrombin is shown to induce hyperpermeability by activating the RhoA pathway and down-regulating the Rac1 pathway.38,39 The APC-mediated barrier-protective effect is believed to stem from APC activation of Rac1.20,29 Our present data show that the FVIIa-mediated barrier-protective effect also involves the activation of Rac1. Like APC, FVIIa may alter the balance between RhoA and Rac1 activation and thus provide protection against thrombin-induced hyperpermeability.

What is the significance of the present finding? FVIIa has proven to be a safe and effective drug for treatment of bleeding episodes in hemophilia patients with inhibitors, and thus is widely used for the treatment of this group of patients.40,41 FVIIa is also used as an adjunctive treatment for serious bleeding in other categories of patients, including patients with severe coagulation defects or patients with a normal coagulation system but who experience excessive or life threatening bleeding as the result of trauma or injury.41,42 Given the current findings, administration of FVIIa to the above groups of patients not only restores hemostasis by thrombin generation, but at the same time may protect the endothelium from barrier disruption of thrombin. Recent studies have suggested that prophylactic treatment with FVIIa in hemophilia patients with inhibitors reduces the frequency of bleedings significantly compared with conventional on-demand hemostatic therapy, and thereby significantly improves the quality of life for these patients.43 Interestingly, prophylactic administration of FVIIa not only decreased hemorrhagic episodes during the 3 months it was administered on a daily basis, but also during the 3-month follow-up period. Given the short biologic half-life of FVIIa in circulation, it was puzzling why once-daily administration of FVIIa during the treatment period also reduces the number of hemorrhagic events during the post-treatment period. Our present observation that the administration of FVIIa prevents vascular leakage associated with inflammation may provide an explanation for the above paradox. Normal moving patterns exert a constant barrier-disruptive force in microvasculature. In a hemophilic patient, vascular integrity may be compromised as the result of impaired generation of low levels of thrombin, which, unlike higher levels of thrombin, has been shown to provide a barrier-protective effect on a continuous basis. Prophylactic administration of FVIIa could prevent joint-bleeding in hemophilia by not only stopping early bleeding by generating thrombin, but may also provide a long-term benefit by protecting the integrity of vascular endothelium via EPCR-dependent signaling. It is possible that the barrier-protective effect mediated by FVIIa during the treatment period may lead to continual vascular healing, which allows maintenance of vascular integrity even after discontinuation of FVIIa administration. In this context, it was found that long-term expression of canine FVIIa in hemophilia A and B dogs prevented any spontaneous bleeding episodes, whereas untreated dogs experienced multiple spontaneous bleeding episodes.44

In summary, our findings here establish that FVIIa, upon binding to EPCR, could activate PAR1-mediated cell signaling and initiate endothelial barrier-protective effects. Future studies are required to determine whether FVIIa uses the same mechanisms that APC does in providing barrier-protective effects.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gary Ferrell from C.T.E.'s laboratory for many shipments of reagents. We appreciate discussions with Ulla Hedner, University of Lund, Malmo, Sweden, on the subject.

This work was supported by grants HL 58869 (L.V.M.R.) and HL 65500 (U.R.P.) from the National Institutes of Health. C.T.E. is an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: P.S. designed the research, performed most of the experiments described in the manuscript, analyzed the data, and compiled the figures; R.G. performed experiments involving mice and analyzed the data; H.K. performed permeability experiments and confocal microscopy and analyzed the data; C.A.C. and S.K. performed barrier protection experiments and studies in mice independently of P.S and R.G. to confirm the findings; C.T.E. provided key reagents; U.R.P. contributed to the research design, guided experiments involving siRNAs, and participated in the preparation of manuscript; and L.V.M.R contributed to overall research design, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read the manuscript and contributed to the preparation of the final version.

Conflict-of-interest-disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: L. Vijaya Mohan Rao, Center for Biomedical Research, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler, 11937 US Hwy 271, Tyler, TX 75708; e-mail: Vijay.Rao@uthct.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal