High expression of the ecotropic viral integration site (EVI1) gene is associated with poor outcome in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). In this issue of Blood, Lugthart et al show that EVI1 expression is also associated with a specific gene promoter DNA methylation signature in AML and present evidence for a mechanistic link through interaction between EVI1 and the DNA methyl transferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B.1

DNA methylation has long been associated with gene silencing during normal development2 and in human cancer.3 The majority of DNA methylation in vertebrates occurs as cytosine methylation within the dinucleotide CpG. The association between DNA methylation and gene silencing is strongest for genes with promoters that contain a high density of the dinucleotide CpG in which the cytosine is heavily methylated. Both myelodysplasia and AML have been shown to be associated with abnormal DNA methylation patterns in multiple studies. In the case of myelodysplasia, inhibitors of DNA methylation, including 5-azacytidine and 5-deoxy-2-azacytidine, have been shown to be of clear therapeutic benefit.4 Methods for assessing genome-wide cytosine methylation status have evolved rapidly in recent years. One such method, the HELP assay, has been used to classify AML into distinct prognostic groups independent of other known factors based on the patterns of methylation of specific sets of genes, most of which contain CpG-rich regions.5

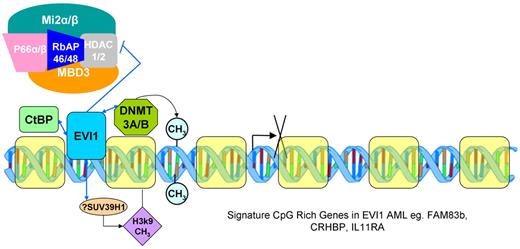

Proposed interactions of EVI1 with DNA methyl transferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B and other components of the epigenetic silencing machinery.

Proposed interactions of EVI1 with DNA methyl transferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B and other components of the epigenetic silencing machinery.

The EVI1 gene is aberrantly overexpressed in up to 8% of cases of AML, many but not all of which involve chromosome 3q26 lesions, and its expression is associated with poor clinical outcomes.1 EVI1 has been shown to associate with the histone methyl transferases SUV39H1 and G9a as well as C-terminal binding protein and to act as a transcriptional repressor.6,7 It has also been shown to associate with BRG-1 and has been implicated in damping the histone deacetylase repressor activity of HDAC1 in the MBD3-NuRD complex,8 suggesting a possible role in transcription activation as well. In the article by Lugthart et al, the HELP assay was used to define a distinct signature of aberrant DNA methylation in CpG-rich promoters in leukemia cells that express EVI1, and an even more pronounced signature in the highest EVI1-expressing cases.1 Furthermore, evidence is presented that EVI1 associates with the DNA methyl transferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B, and that EVI1 binds in vivo to a group of gene promoters included in the hypermethylated gene promoter signature set of EVI1-positive AMLs. Previous studies have shown that the oncogenic transcription factor PML-RARA may mediate recruitment of DNA methyl transferases and subsequent promoter hypermethylation.9 EV1-expressing AML provides another example of how aberrant methylation of genes in cancer cells can be determined specifically rather than entirely stochastically by selective pressure for growth or survival advantage.

Several important questions remain about the interplay among EVI1, aberrant DNA methylation of specific genes, and leukemogenesis (see figure). Because histone methylation by SUV39H1 has been shown to be critical for some DNA methylation events,2 it remains unclear whether EVI1 directs methylation of the genes to which it binds strictly by recruiting DNMT3A and/or DNMT3B, or whether histone methylation also plays a role. The expression pattern of the hypermethylated signature gene set in EVI1-positive leukemia was not directly determined by Lugthart et al.1 Because EVI1 has also been associated in vitro with gene activation mechanisms and because methylated CpG-rich genes can in some cases be expressed,10 the exact causal link between EVI1 and silencing of a specific tumor suppressor gene or genes and leukemogenesis remains to be determined. As noted in the article, animal models will be required to definitively answer some of these questions. Nonetheless, the association between EVI1 expression, and a distinct hypermethylation signature of CpG-rich promoters, including those of several putative tumor suppressor genes, is an important finding with clear implications for understanding the pathogenesis of (and potentially developing more effective targeted therapy for) this high-risk group of AMLs. It is also clear that the concept of a role for aberrant DNA methylation and the components of the epigenetic machinery in the pathogenesis of AML continues to gain momentum, and we can expect to see more examples of these relationships emerging in the near future.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal