Abstract

To identify factors to improve the outcomes of related and unrelated allogeneic stem cell transplantations (allo-SCT) for Philadelphia chromosome–negative acute lymphocytic leukemia (Ph− ALL) in the first complete remission (CR1), we retrospectively analyzed 1139 Ph− ALL patients using the registry data, particularly the details of 641 patients transplanted in CR1. Overall survival was significantly superior among patients transplanted in CR1, but no significant difference was observed between related and unrelated allo-SCTs (related vs unrelated: 65% vs 62% at 4 years, respectively; P = .19). Among patients transplanted in CR1, relapse rates were significantly higher in related allo-SCT compared with unrelated allo-SCT, and multivariate analysis demonstrated that less than 6 months from diagnosis to allo-SCT alone was associated with relapse. On the other hand, nonrelapse mortality (NRM) was significantly higher in unrelated allo-SCT compared with related allo-SCT, and multivariate analysis demonstrated that 10 months or longer from diagnosis to allo-SCT, human leukocyte antigen mismatch, and abnormal karyotype were associated with NRM. In conclusion, our study showed comparable survival rates but different relapse rates, NRM rates, and risk factors between related and unrelated allo-SCTs. After a close consideration of these factors, the outcome of allo-SCT for adult Ph− ALL in CR1 could be improved.

Introduction

The indication of allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT) for Philadelphia chromosome–negative acute lymphocytic leukemia (Ph− ALL) is still controversial.1,2 As for related allo-SCT, one prospective study suggested that related allo-SCT for Ph− ALL in first complete remission (CR1) could provide the most potent antileukemic therapy and considerable survival benefits.3 As for unrelated allo-SCT, the largest retrospective study of Ph− ALL patients in CR1 showed worse overall survival (OS) rates because of higher incidences of nonrelapse morality (NRM) than those in related allo-SCT,4 whereas another reported that there were no differences in OS rates and NRM rates between related and unrelated allo-SCTs for adult ALL in CR1.5 These data indicated that unrelated allo-SCT could also be a treatment option for adult Ph− ALL patients in CR1 if NRM rates were low enough, although it is not yet routinely performed.

Although the analyses of the outcome of allo-SCT alone have some biases, such as excluding death during chemotherapy, and there may be potential differences in the baseline characteristics of patients between related and unrelated allo-SCTs, the comparison of transplantation outcomes and risk factors between related and unrelated allo-SCTs for adult Ph− ALL could indicate strategies to improve transplantation outcomes for this disease. We particularly focused on allo-SCT in CR1 because this is the area of controversy.

Methods

Collection of data and data sources

The recipients' clinical data were provided by the Japan Society for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (JSHCT) and the Japan Marrow Donor Program (JMDP). Both JSHCT and JMDP collect recipients' clinical data at 100 days after allo-SCT. The patient's data on survival, disease status, and long-term complications, including chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and second malignancies, are renewed annually by follow-up forms. More than 99% of unrelated allo-SCT in Japan was captured in the JMDP database, and approximately 75% of related allo-SCT was captured in the JSHCT database. This study was approved by the data management committees of JSHCT and JMDP. Informed consent was obtained from both recipients and donors in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

Data of 1976 patients who underwent their first allo-SCT for Ph− ALL between 1993 and 2007 were available in the registration database of JSHCT and JMDP. Excluding 662 patients whose age was 15 years or younger, 67 patients without data of GVHD prophylaxis and the interval from diagnosis to allo-SCT, 22 patients who underwent 2 or more human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci mismatched related allo-SCT, and 86 patients who received reduced-intensity conditioning regimens, we analyzed 1139 adult Ph− ALL patients (499 related and 640 unrelated). We particularly analyzed details of 641 patients transplanted in CR1, according to donor types (310 related and 331 unrelated). All but 4 patients were donated from Japanese donors harvested in Japanese harvest centers. Only bone marrow grafts were used in unrelated allo-SCT because peripheral blood stem cell donation from unrelated donors is not yet approved in Japan. HLA high-resolution molecular typing methods were performed for HLA-A, -B, -Cw, and -DRB1 for all patients in JMDP. Donor and recipient pairs were considered matched when HLA was matched at -A, -B, and -DRB1 loci in related allo-SCT and at -A, -B, -Cw, and -DRB1 loci in unrelated allo-SCT. Mismatches were defined as at least one disparity of these loci.

Definition

Neutrophil recovery was defined by an absolute neutrophil count of at least 0.5 × 109/L for 3 consecutive days; platelet recovery was defined by a count of at least 50 × 109/L without transfusion support. Acute and chronic GVHD was diagnosed and graded according to consensus criteria.6,7 Relapse was defined as hematologic leukemia recurrence. NRM was defined as death during continuous remission. For analyses of OS, failure was death from any cause, and surviving patients were censored at the date of last contact. The date of allo-SCT was the starting time point for calculating all outcomes. Patients were classified at diagnosis by the Japan Adult leukemia Study Group (JALSG) risk stratification: low risk was defined as less than 30 years at diagnosis and white blood cell count less than 30 000/μL at diagnosis, high risk as 30 years or more at diagnosis and white blood cell count 30 000/μL or more at diagnosis, and intermediate risk as other.8 To determine the cut-off for the upper limit of tolerability by age, we analyzed the cumulative incidence of NRM by categorizing the patients' age every 5 years. Because NRM rates of 45- to 49-year-old and 50-year-old or older categories showed higher incidences compared with other categories, we determined the best cut-off point as 45 years old.

Statistical analysis

The 2-sided χ2 test was used for categorical variables. OS rates were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and P values were calculated using a log-rank test.9,10 Cumulative incidences of relapse, NRM, and GVHD were calculated by the Gray method.11,12 Death without relapse was considered as a competing event for relapse, and relapse as a competing event for NRM. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazard regression model.13 A significance level of P less than .05 was used for all analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of 1139 patients, 641 received allo-SCT in CR1 (310 related and 331 unrelated), 199 in subsequent remission (56 related and 143 unrelated), and 299 in nonremission (133 related and 166 unrelated). The characteristics of the patients transplanted in CR1 are shown in Table 1. The frequencies of HLA mismatched donor and tacrolimus-based GVHD prophylaxis were higher, and the interval from diagnosis to allo-SCT was longer among patients who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT than among those who underwent a related allo-SCT. There was no significant difference in the age at allo-SCT, the white blood cell counts at diagnosis, JALSG risk stratification, and year of allo-SCT between related and unrelated allo-SCTs.

Characteristics of patients transplanted in CR1, according to donor type

| No. of patients . | Related (n = 310) . | Unrelated (n = 331) . | P . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. . | % . | No. . | % . | ||

| Median WBC count at diagnosis/μL (range) | 10 250 (109-328 000) | 11 000 (700-892 000) | .43 | ||

| Median patient age at allo-SCT, y (range) | 30 (16-66) | 31 (16-59) | .95 | ||

| 16-20 | 66 | 21.3 | 77 | 23.3 | |

| 21-30 | 93 | 30.0 | 82 | 24.8 | |

| 31-40 | 71 | 22.9 | 86 | 26.0 | |

| 41-50 | 58 | 18.7 | 68 | 20.5 | |

| 51 or older | 22 | 7.1 | 18 | 5.4 | |

| Sex | .09 | ||||

| Male | 157 | 50.6 | 190 | 57.4 | |

| Female | 153 | 49.4 | 141 | 42.6 | |

| Source | < .0001 | ||||

| BM | 212 | 68.4 | 331 | 100.0 | |

| PB | 98 | 31.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Lineage | .01 | ||||

| T | 50 | 16.1 | 54 | 16.3 | |

| B | 218 | 70.3 | 203 | 61.3 | |

| Other | 42 | 13.5 | 74 | 22.4 | |

| Cytogenetics | .07 | ||||

| Normal | 193 | 62.3 | 208 | 62.8 | |

| t(4;11) | 11 | 3.5 | 5 | 1.5 | |

| Other MLL/11q23 translocations | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.9 | |

| t(1;19) | 10 | 3.2 | 6 | 1.8 | |

| t(8;14) | 3 | 1.0 | 3 | 0.9 | |

| 14q32 translocations | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| del(6q) | 3 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| del(7p) | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| −7* | 5 | 1.6 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| +8* | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| +X* | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| del(9p) | 3 | 1.0 | 9 | 2.7 | |

| abnormality of 11q | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.9 | |

| del(12p) | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| del(13q)/−13 | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| del(17p) | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Complex | 10 | 3.2 | 15 | 4.5 | |

| Low hypodiploidy/near triploidy | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| High hyperdiploidy | 16 | 5.2 | 12 | 3.6 | |

| Other abnormality (no t(9;22))† | 45 | 14.5 | 58 | 17.5 | |

| JALSG risk stratification | .21 | ||||

| Low | 39 | 12.6 | 45 | 13.6 | |

| Intermediate | 163 | 52.6 | 192 | 58.0 | |

| High | 108 | 34.8 | 94 | 28.4 | |

| HLA matching | < .0001 | ||||

| Match | 285 | 91.9 | 192 | 58.0 | |

| Class I 1 locus-mismatch | 18 | 5.8 | 53 | 16.0 | |

| Class II 1 locus-mismatch | 7 | 2.3 | 32 | 9.7 | |

| 2 or more loci mismatch | 0 | 0.0 | 54 | 16.3 | |

| Time from diagnosis to transplantation, mo (range) | 5.7 (1.9-36.6) | 10.0 (4.0-43.0) | < .0001 | ||

| < 6 | 169 | 54.5 | 23 | 6.9 | |

| 6-9 | 109 | 35.2 | 143 | 43.2 | |

| 10 or longer | 32 | 10.3 | 165 | 49.8 | |

| Preparative regimen | .004 | ||||

| CY + TBI | 140 | 45.2 | 156 | 47.1 | |

| CA + CY + TBI | 66 | 21.3 | 84 | 25.4 | |

| BU + CY + TBI | 17 | 5.5 | 15 | 4.5 | |

| VP + CY + TBI | 23 | 7.4 | 32 | 9.7 | |

| Other TBI myeloablative regimens | 39 | 12.6 | 32 | 9.7 | |

| BU + CY | 17 | 5.5 | 12 | 3.6 | |

| Other non-TBI myeloablative regimens | 8 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| GVHD prophylaxis | < .0001 | ||||

| Cyclosporine A with or without other | 283 | 91.3 | 171 | 51.7 | |

| Tacrolimus with or without other | 27 | 8.7 | 160 | 48.3 | |

| Years of allo-SCT | .26 | ||||

| 1993-1997 | 48 | 15.5 | 55 | 16.6 | |

| 1998-2002 | 132 | 42.6 | 120 | 36.3 | |

| 2003-2007 | 130 | 41.9 | 156 | 47.1 | |

| No. of patients . | Related (n = 310) . | Unrelated (n = 331) . | P . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. . | % . | No. . | % . | ||

| Median WBC count at diagnosis/μL (range) | 10 250 (109-328 000) | 11 000 (700-892 000) | .43 | ||

| Median patient age at allo-SCT, y (range) | 30 (16-66) | 31 (16-59) | .95 | ||

| 16-20 | 66 | 21.3 | 77 | 23.3 | |

| 21-30 | 93 | 30.0 | 82 | 24.8 | |

| 31-40 | 71 | 22.9 | 86 | 26.0 | |

| 41-50 | 58 | 18.7 | 68 | 20.5 | |

| 51 or older | 22 | 7.1 | 18 | 5.4 | |

| Sex | .09 | ||||

| Male | 157 | 50.6 | 190 | 57.4 | |

| Female | 153 | 49.4 | 141 | 42.6 | |

| Source | < .0001 | ||||

| BM | 212 | 68.4 | 331 | 100.0 | |

| PB | 98 | 31.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Lineage | .01 | ||||

| T | 50 | 16.1 | 54 | 16.3 | |

| B | 218 | 70.3 | 203 | 61.3 | |

| Other | 42 | 13.5 | 74 | 22.4 | |

| Cytogenetics | .07 | ||||

| Normal | 193 | 62.3 | 208 | 62.8 | |

| t(4;11) | 11 | 3.5 | 5 | 1.5 | |

| Other MLL/11q23 translocations | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.9 | |

| t(1;19) | 10 | 3.2 | 6 | 1.8 | |

| t(8;14) | 3 | 1.0 | 3 | 0.9 | |

| 14q32 translocations | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| del(6q) | 3 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| del(7p) | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| −7* | 5 | 1.6 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| +8* | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| +X* | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| del(9p) | 3 | 1.0 | 9 | 2.7 | |

| abnormality of 11q | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.9 | |

| del(12p) | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| del(13q)/−13 | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| del(17p) | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Complex | 10 | 3.2 | 15 | 4.5 | |

| Low hypodiploidy/near triploidy | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| High hyperdiploidy | 16 | 5.2 | 12 | 3.6 | |

| Other abnormality (no t(9;22))† | 45 | 14.5 | 58 | 17.5 | |

| JALSG risk stratification | .21 | ||||

| Low | 39 | 12.6 | 45 | 13.6 | |

| Intermediate | 163 | 52.6 | 192 | 58.0 | |

| High | 108 | 34.8 | 94 | 28.4 | |

| HLA matching | < .0001 | ||||

| Match | 285 | 91.9 | 192 | 58.0 | |

| Class I 1 locus-mismatch | 18 | 5.8 | 53 | 16.0 | |

| Class II 1 locus-mismatch | 7 | 2.3 | 32 | 9.7 | |

| 2 or more loci mismatch | 0 | 0.0 | 54 | 16.3 | |

| Time from diagnosis to transplantation, mo (range) | 5.7 (1.9-36.6) | 10.0 (4.0-43.0) | < .0001 | ||

| < 6 | 169 | 54.5 | 23 | 6.9 | |

| 6-9 | 109 | 35.2 | 143 | 43.2 | |

| 10 or longer | 32 | 10.3 | 165 | 49.8 | |

| Preparative regimen | .004 | ||||

| CY + TBI | 140 | 45.2 | 156 | 47.1 | |

| CA + CY + TBI | 66 | 21.3 | 84 | 25.4 | |

| BU + CY + TBI | 17 | 5.5 | 15 | 4.5 | |

| VP + CY + TBI | 23 | 7.4 | 32 | 9.7 | |

| Other TBI myeloablative regimens | 39 | 12.6 | 32 | 9.7 | |

| BU + CY | 17 | 5.5 | 12 | 3.6 | |

| Other non-TBI myeloablative regimens | 8 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| GVHD prophylaxis | < .0001 | ||||

| Cyclosporine A with or without other | 283 | 91.3 | 171 | 51.7 | |

| Tacrolimus with or without other | 27 | 8.7 | 160 | 48.3 | |

| Years of allo-SCT | .26 | ||||

| 1993-1997 | 48 | 15.5 | 55 | 16.6 | |

| 1998-2002 | 132 | 42.6 | 120 | 36.3 | |

| 2003-2007 | 130 | 41.9 | 156 | 47.1 | |

WBC indicates white blood cell; BM, bone marrow; PB, peripheral blood; related HLA match, identical HLA-A, -B, and -DRB1 loci; unrelated HLA match, HLA-A, -B, -Cw, and -DRB1 loci; HLA mismatch, at least one disparity at one of these loci; CY, cyclophosphamide; TBI, total body irradiation; CA, cytarabine; BU, busulfan; and VP, etoposide.

These groups exclude cases with low hypodiploidy and high hyperdiploidy.

Abnormal karyotypes excluding those with any of the aforementioned abnormalities.

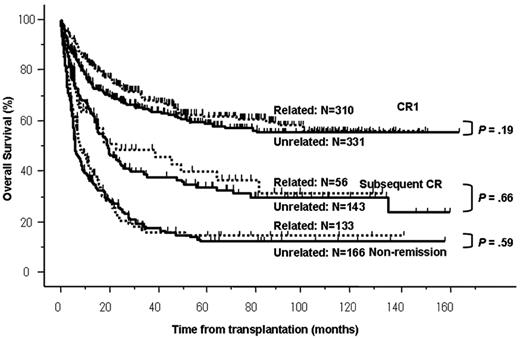

Survival

Median follow-up periods among survivors were 47.7 months (range, 1.3-162 months). OS rates at 4 years were 64% in CR1, 39% in subsequent CR, and 16% in non-remission (P < .0001). Although OS rates were significantly different among disease stages at allo-SCT, there were no significant differences in OS rates at 4 years between related and unrelated allo-SCTs in any disease stage (related vs unrelated: 65% vs 62% in CR1, P = .19; 44% vs 38% in subsequent CR, P = .66; and 17% vs 16% in non-remission, P = .59; respectively; Figure 1). There was no statistical difference in OS rates and NRM rates over transplantation years (data not shown). Among 641 patients transplanted in CR1, JALSG risk stratification did not have a significant impact on the OS after allo-SCT (68% in low risk, 62% in intermediate risk, and 58% in high risk, at 4 years, respectively; P = .31). To address our main issue, we performed the following analyses among patients transplanted in CR1 according to donor types.

OS according to disease status and donor type. OS rates were significantly superior among patients transplanted in CR1. There was no significant difference between related and unrelated allo-SCTs (related vs unrelated: 65% vs 62% in CR1, P = .19; 44% vs 38% in subsequent CR, P = .66; and 17% vs 16% in nonremission, P = .59; respectively).

OS according to disease status and donor type. OS rates were significantly superior among patients transplanted in CR1. There was no significant difference between related and unrelated allo-SCTs (related vs unrelated: 65% vs 62% in CR1, P = .19; 44% vs 38% in subsequent CR, P = .66; and 17% vs 16% in nonremission, P = .59; respectively).

Among 310 patients who underwent a related allo-SCT in CR1, multivariate analysis showed that age at allo-SCT and less than 6 months from diagnosis to allo-SCT were significant risk factors for OS. Among 331 patients who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT in CR1, multivariate analysis showed that abnormal karyotype [except for t(4;11) and t(1;19)], HLA mismatch, and 10 months or longer from diagnosis to allo-SCT were significant risk factors for OS (Table 2).

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors influencing OS among patients transplanted in CR1, according to donor type

| Covariates . | Related (n = 310) . | Unrelated (n = 331) . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | N . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | |||||

| HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | |||

| WBC count at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| < 30 000/μL | 224 | 1.00 | — | 230 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 30 000/μL or more at diagnosis | 86 | 1.19 (0.78-1.82) | .42 | — | 101 | 0.83 (0.56-1.25) | .38 | — | ||

| Lineage | ||||||||||

| B | 218 | 1.00 | — | 203 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| T | 50 | 0.73 (0.34-1.77) | .52 | — | 54 | 0.81 (0.44-1.48) | .35 | — | ||

| Other | 42 | 0.94 (0.54-1.64) | .84 | — | 74 | 1.08 (0.70-1.67) | .72 | — | ||

| Karyotype | ||||||||||

| Normal | 193 | 1.00 | — | 208 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| t(4;11) or t(1;19) | 21 | 0.51 (0.14-1.54) | .19 | — | 11 | 1.49 (0.54-4.09) | .44 | 1.59 (0.58-4.36) | .37 | |

| Other (no t(9;22)) | 96 | 1.03 (0.67-7.14) | .89 | — | 112 | 1.49 (1.03-2.17) | .04 | 1.43 (1.13-2.40) | .01 | |

| JALSG risk stratification | ||||||||||

| Low | 39 | 1.00 | — | 45 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Intermediate | 163 | 1.36 (0.87-2.12) | .18 | — | 192 | 1.06 (0.71-1.59) | .77 | — | ||

| High | 108 | 1.77 (0.95-3.31) | .07 | — | 94 | 1.02 (0.56-1.88) | .94 | — | ||

| Age at allo-SCT | ||||||||||

| < 45 y old | 255 | 1.00 | — | 281 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 45 y old or older at allo-SCT | 55 | 2.04 (1.30-3.13) | .002 | 2.13 (1.36-3.34) | .0009 | 50 | 1.05 (0.63-1.73) | .86 | ||

| HLA | ||||||||||

| Match | 285 | 1.00 | — | 192 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Mismatch | 25 | 0.95 (0.46-1.96) | .90 | — | 139 | 1.44 (1.01-2.06) | .04 | 1.45 (1.01-2.07) | .04 | |

| Stem cell source | ||||||||||

| Bone marrow | 212 | 1.00 | — | — | ||||||

| Peripheral blood | 98 | 1.43 (0.94-2.13) | .09 | 1.40 (0.93-2.11) | .11 | |||||

| Time from diagnosis to allo-SCT | ||||||||||

| 6 mo or longer | 169 | 1.00 | — | 23 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| < 6 mo | 141 | 1.75 (1.16-2.63) | .007 | 1.80 (1.19-2.71) | .005 | 308 | 0.33 (0.10-1.04) | .06 | — | |

| < 10 mo | 278 | 1.00 | — | 166 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 10 mo or longer | 32 | 0.56 (0.26-1.20) | .14 | — | 165 | 1.54 (1.07-2.21) | .02 | 1.62 (1.12-2.34) | .01 | |

| Preparative regimen | ||||||||||

| Non-TBI regimens | 25 | 1.00 | — | 12 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| TBI regimens | 285 | 0.72 (0.38-1.35) | .30 | — | 319 | 0.59 (0.27-1.26) | .17 | — | ||

| GVHD prophylaxis | ||||||||||

| Cyclosporine A with or without other | 283 | 1.00 | — | 171 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Tacrolimus with or without other | 27 | 2.02 (1.15-3.56) | .01 | — | 160 | 1.38 (0.96-1.97) | .08 | — | ||

| Covariates . | Related (n = 310) . | Unrelated (n = 331) . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | N . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | |||||

| HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | |||

| WBC count at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| < 30 000/μL | 224 | 1.00 | — | 230 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 30 000/μL or more at diagnosis | 86 | 1.19 (0.78-1.82) | .42 | — | 101 | 0.83 (0.56-1.25) | .38 | — | ||

| Lineage | ||||||||||

| B | 218 | 1.00 | — | 203 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| T | 50 | 0.73 (0.34-1.77) | .52 | — | 54 | 0.81 (0.44-1.48) | .35 | — | ||

| Other | 42 | 0.94 (0.54-1.64) | .84 | — | 74 | 1.08 (0.70-1.67) | .72 | — | ||

| Karyotype | ||||||||||

| Normal | 193 | 1.00 | — | 208 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| t(4;11) or t(1;19) | 21 | 0.51 (0.14-1.54) | .19 | — | 11 | 1.49 (0.54-4.09) | .44 | 1.59 (0.58-4.36) | .37 | |

| Other (no t(9;22)) | 96 | 1.03 (0.67-7.14) | .89 | — | 112 | 1.49 (1.03-2.17) | .04 | 1.43 (1.13-2.40) | .01 | |

| JALSG risk stratification | ||||||||||

| Low | 39 | 1.00 | — | 45 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Intermediate | 163 | 1.36 (0.87-2.12) | .18 | — | 192 | 1.06 (0.71-1.59) | .77 | — | ||

| High | 108 | 1.77 (0.95-3.31) | .07 | — | 94 | 1.02 (0.56-1.88) | .94 | — | ||

| Age at allo-SCT | ||||||||||

| < 45 y old | 255 | 1.00 | — | 281 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 45 y old or older at allo-SCT | 55 | 2.04 (1.30-3.13) | .002 | 2.13 (1.36-3.34) | .0009 | 50 | 1.05 (0.63-1.73) | .86 | ||

| HLA | ||||||||||

| Match | 285 | 1.00 | — | 192 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Mismatch | 25 | 0.95 (0.46-1.96) | .90 | — | 139 | 1.44 (1.01-2.06) | .04 | 1.45 (1.01-2.07) | .04 | |

| Stem cell source | ||||||||||

| Bone marrow | 212 | 1.00 | — | — | ||||||

| Peripheral blood | 98 | 1.43 (0.94-2.13) | .09 | 1.40 (0.93-2.11) | .11 | |||||

| Time from diagnosis to allo-SCT | ||||||||||

| 6 mo or longer | 169 | 1.00 | — | 23 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| < 6 mo | 141 | 1.75 (1.16-2.63) | .007 | 1.80 (1.19-2.71) | .005 | 308 | 0.33 (0.10-1.04) | .06 | — | |

| < 10 mo | 278 | 1.00 | — | 166 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 10 mo or longer | 32 | 0.56 (0.26-1.20) | .14 | — | 165 | 1.54 (1.07-2.21) | .02 | 1.62 (1.12-2.34) | .01 | |

| Preparative regimen | ||||||||||

| Non-TBI regimens | 25 | 1.00 | — | 12 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| TBI regimens | 285 | 0.72 (0.38-1.35) | .30 | — | 319 | 0.59 (0.27-1.26) | .17 | — | ||

| GVHD prophylaxis | ||||||||||

| Cyclosporine A with or without other | 283 | 1.00 | — | 171 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Tacrolimus with or without other | 27 | 2.02 (1.15-3.56) | .01 | — | 160 | 1.38 (0.96-1.97) | .08 | — | ||

HR indicates hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; WBC, white blood cell; —, not applicable; and TBI, total body irradiation.

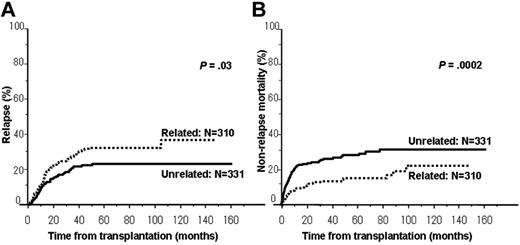

Relapse and NRM among patients transplanted in CR1

The cumulative incidence of relapse was significantly higher in patients who underwent a related allo-SCT compared with those who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT (related vs unrelated: 32% vs 22% at 4 years, P = .03; Figure 2A). Multivariate analyses according to donor type showed that less than 6 months from diagnosis to allo-SCT alone was associated with relapse among 310 patients who underwent a related allo-SCT in CR1, whereas only abnormal karyotype [except for t(4;11) and t(1;19)] was associated with relapse among 331 patients who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT in CR1 (Table 3).

Cumulative incidence of relapse and NRM in patients transplanted in CR1 according to donor type. (A) Cumulative incidence of relapse among patients transplanted in CR1 was significantly higher in patients who underwent a related allo-SCT compared with those who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT (related vs unrelated: 32% vs 22% at 4 years, P = .03). (B) Cumulative incidence of NRM among patients transplanted in CR1 was significantly higher in patients who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT compared with those who underwent a related allo-SCT (related vs unrelated: 14% vs 27% at 4 years, P = .0002).

Cumulative incidence of relapse and NRM in patients transplanted in CR1 according to donor type. (A) Cumulative incidence of relapse among patients transplanted in CR1 was significantly higher in patients who underwent a related allo-SCT compared with those who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT (related vs unrelated: 32% vs 22% at 4 years, P = .03). (B) Cumulative incidence of NRM among patients transplanted in CR1 was significantly higher in patients who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT compared with those who underwent a related allo-SCT (related vs unrelated: 14% vs 27% at 4 years, P = .0002).

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors influencing relapse among patients transplanted in CR1, according to donor type

| Covariates . | Related (n = 310) . | Unrelated (n = 331) . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | N . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | |||||

| HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | |||

| WBC count at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| < 30 000/μL | 224 | 1.00 | — | 230 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 30 000/μL or more at diagnosis | 86 | 0.88 (0.52-1.47) | .62 | — | 101 | 1.11 (0.62-1.98) | .72 | — | ||

| Lineage | ||||||||||

| B | 218 | 1.00 | — | 203 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| T | 50 | 0.54 (0.22-1.37) | .09 | — | 54 | 1.31 (0.57-3.02) | .62 | — | ||

| Other | 42 | 1.21 (0.66-2.21) | .54 | — | 74 | 1.06 (0.53-2.11) | .87 | — | ||

| Karyotype | ||||||||||

| Normal | 193 | 1.00 | — | 208 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| t(4;11) or t(1;19) | 21 | 0.64 (0.19-2.12) | .36 | — | 11 | 1.97 (0.46-8.35) | .91 | — | ||

| Other (no t(9;22)) | 96 | 1.11 (0.68-1.82) | .67 | — | 112 | 2.15 (1.24-3.73) | .01 | 2.15 (1.24-3.73) | .01 | |

| JALSG risk stratification | ||||||||||

| Low | 39 | 1.00 | — | 45 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Intermediate | 163 | 0.96 (0.59-1.55) | .87 | — | 192 | 1.04 (0.57-1.91) | .90 | — | ||

| High | 108 | 0.81 (0.35-1.84) | .61 | — | 94 | 1.04 (0.43-2.52) | .94 | — | ||

| Age at allo-SCT | ||||||||||

| < 45 y old | 255 | 1.00 | — | 281 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 45 y old or older at allo-SCT | 55 | 0.82 (0.41-1.64) | .57 | — | 50 | 0.74 (0.42-1.32) | .08 | — | ||

| HLA | ||||||||||

| Match | 285 | 1.00 | — | 192 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Mismatch | 25 | 0.82 (0.33-2.02) | .66 | — | 139 | 0.74 (0.42-1.32) | .31 | — | ||

| Stem cell source* | ||||||||||

| Bone marrow | 212 | 1.00 | — | — | ||||||

| Peripheral blood | 98 | 1.07 (0.65-1.76) | .79 | — | — | |||||

| Time from diagnosis to allo-SCT | ||||||||||

| 6 mo or longer | 169 | 1.00 | — | 23 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| < 6 mo | 141 | 1.68 (1.05-2.69) | .03 | 1.68 (1.05-2.69) | .03 | 308 | 0.47 (0.11-1.92) | .29 | — | |

| < 10 mo | 278 | 1.00 | — | 166 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 10 mo or longer | 32 | 0.49 (0.18-1.34) | .16 | — | 165 | 0.92 (0.54-1.58) | .76 | — | ||

| Preparative regimen | ||||||||||

| Non-TBI regimens | 25 | 1.00 | — | 12 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| TBI regimens | 285 | 0.62 (0.31-1.25) | .18 | — | 319 | 0,47 (0.15-1.52) | .21 | — | ||

| GVHD prophylaxis | ||||||||||

| Cyclosporine A with or without other | 283 | 1.00 | — | 171 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Tacrolimus with or without other | 27 | 1.62 (0.81-3.26) | .18 | — | 160 | 1.39 (0.81-2.38) | .24 | — | ||

| Covariates . | Related (n = 310) . | Unrelated (n = 331) . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | N . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | |||||

| HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | |||

| WBC count at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| < 30 000/μL | 224 | 1.00 | — | 230 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 30 000/μL or more at diagnosis | 86 | 0.88 (0.52-1.47) | .62 | — | 101 | 1.11 (0.62-1.98) | .72 | — | ||

| Lineage | ||||||||||

| B | 218 | 1.00 | — | 203 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| T | 50 | 0.54 (0.22-1.37) | .09 | — | 54 | 1.31 (0.57-3.02) | .62 | — | ||

| Other | 42 | 1.21 (0.66-2.21) | .54 | — | 74 | 1.06 (0.53-2.11) | .87 | — | ||

| Karyotype | ||||||||||

| Normal | 193 | 1.00 | — | 208 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| t(4;11) or t(1;19) | 21 | 0.64 (0.19-2.12) | .36 | — | 11 | 1.97 (0.46-8.35) | .91 | — | ||

| Other (no t(9;22)) | 96 | 1.11 (0.68-1.82) | .67 | — | 112 | 2.15 (1.24-3.73) | .01 | 2.15 (1.24-3.73) | .01 | |

| JALSG risk stratification | ||||||||||

| Low | 39 | 1.00 | — | 45 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Intermediate | 163 | 0.96 (0.59-1.55) | .87 | — | 192 | 1.04 (0.57-1.91) | .90 | — | ||

| High | 108 | 0.81 (0.35-1.84) | .61 | — | 94 | 1.04 (0.43-2.52) | .94 | — | ||

| Age at allo-SCT | ||||||||||

| < 45 y old | 255 | 1.00 | — | 281 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 45 y old or older at allo-SCT | 55 | 0.82 (0.41-1.64) | .57 | — | 50 | 0.74 (0.42-1.32) | .08 | — | ||

| HLA | ||||||||||

| Match | 285 | 1.00 | — | 192 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Mismatch | 25 | 0.82 (0.33-2.02) | .66 | — | 139 | 0.74 (0.42-1.32) | .31 | — | ||

| Stem cell source* | ||||||||||

| Bone marrow | 212 | 1.00 | — | — | ||||||

| Peripheral blood | 98 | 1.07 (0.65-1.76) | .79 | — | — | |||||

| Time from diagnosis to allo-SCT | ||||||||||

| 6 mo or longer | 169 | 1.00 | — | 23 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| < 6 mo | 141 | 1.68 (1.05-2.69) | .03 | 1.68 (1.05-2.69) | .03 | 308 | 0.47 (0.11-1.92) | .29 | — | |

| < 10 mo | 278 | 1.00 | — | 166 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 10 mo or longer | 32 | 0.49 (0.18-1.34) | .16 | — | 165 | 0.92 (0.54-1.58) | .76 | — | ||

| Preparative regimen | ||||||||||

| Non-TBI regimens | 25 | 1.00 | — | 12 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| TBI regimens | 285 | 0.62 (0.31-1.25) | .18 | — | 319 | 0,47 (0.15-1.52) | .21 | — | ||

| GVHD prophylaxis | ||||||||||

| Cyclosporine A with or without other | 283 | 1.00 | — | 171 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Tacrolimus with or without other | 27 | 1.62 (0.81-3.26) | .18 | — | 160 | 1.39 (0.81-2.38) | .24 | — | ||

HR indicates hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; WBC, white blood cell; —, not applicable; and TBI, total body irradiation.

Stem cell source (peripheral blood) was not a significant risk factor for relapse in the multivariate analysis.

The cumulative incidence of NRM was significantly higher in patients who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT compared with those who underwent a related allo-SCT (related vs unrelated: 14% vs 27% at 4 years, P = .0002; Figure 2B). Multivariate analyses according to donor type showed that age only 45 years or older at allo-SCT was associated with NRM among 310 patients who underwent a related allo-SCT in CR1, whereas abnormal karyotype [except for t(4;11) and t(1;19)], HLA mismatch, and 10 months or longer from diagnosis to allo-SCT were associated with NRM among 331 patients who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT in CR1 (Table 4).

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors influencing NRM among patients transplanted in CR1, according to donor type

| Covariates . | Related (n = 310) . | Unrelated (n = 331) . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | N . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | |||||

| HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | |||

| WBC count at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| < 30 000/μL | 224 | 1.00 | — | 230 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 30 000/μL or more at diagnosis | 86 | 1.21 (0.63-2.34) | .57 | — | 101 | 0.79 (0.48-1.30) | .35 | — | ||

| Lineage | ||||||||||

| B | 218 | 1.00 | — | 203 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| T | 50 | 1.25 (0.41-3.81) | .53 | — | 54 | 0.62 (0.29-1.38) | .17 | — | ||

| Other | 42 | 0.87 (0.34-2.26) | .78 | — | 74 | 1.08 (0.65-1.81) | .76 | — | ||

| Karyotype | ||||||||||

| Normal | 193 | 1.00 | — | 208 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| t(4;11) or t(1;19) | 21 | 0.77 (0.16-3.17) | .73 | — | 11 | 1.03 (0.25-4.30) | .63 | 1.11 (0.27-4.64) | .57 | |

| Other (no t(9;22)) | 96 | 0.92 (0.47-1.81) | .81 | — | 112 | 1.47 (0.94-2.29) | .09 | 1.67 (1.06-2.64) | .03 | |

| JALSG risk stratification | ||||||||||

| Low | 39 | 1.00 | — | 45 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Intermediate | 163 | 1.85 (0.86-3.97) | .12 | — | 192 | 1.01 (0.62-1.65) | .96 | — | ||

| High | 108 | 2.82 (1.09-7.31) | .03 | — | 94 | 1.03 (0.50-2.10) | .94 | — | ||

| Age at allo-SCT | ||||||||||

| < 45 y old | 255 | 1.00 | — | 281 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 45 y old or older at allo-SCT | 55 | 3.90 (2.09-7.25) | < .0001 | 3.90 (2.09-7.25) | < .0001 | 50 | 1.26 (0.72-2.20) | .42 | ||

| HLA | ||||||||||

| Match | 285 | 1.00 | — | 192 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Mismatch | 25 | 1.64 (0.64-4.18) | .30 | — | 139 | 1.69 (1.10-2.60) | .02 | 1.69 (1.10-2.61) | .02 | |

| Stem cell source | ||||||||||

| Bone marrow | 212 | 1.00 | — | — | ||||||

| Peripheral blood | 98 | 1.75 (0.94-3.28) | .08 | — | — | |||||

| Time from diagnosis to allo-SCT | ||||||||||

| 6 mo or longer | 169 | 1.00 | — | 23 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| < 6 mo | 141 | 1.64 (0.87-3.11) | .13 | — | 308 | 0.31 (0.08-1.25) | .10 | — | ||

| < 10 mo | 278 | 1.00 | — | 166 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 10 mo or longer | 32 | 1.07 (0.42-2.72) | .89 | — | 165 | 1.90 (1.21-2.99) | .01 | 1.98 (1.26-3.13) | .003 | |

| Preparative regimen | ||||||||||

| Non-TBI regimens | 25 | 1.00 | — | 12 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| TBI regimens | 285 | 0.63 (0.25-1.61) | .34 | — | 319 | 0.67 (0.25-1.85) | .44 | — | ||

| GVHD prophylaxis | ||||||||||

| Cyclosporine A with or without other | 283 | 1.00 | — | 171 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Tacrolimus with or without other | 27 | 1.66 (0.65-3.80) | .29 | — | 160 | 1.33 (0.86-2.05) | .52 | — | ||

| Covariates . | Related (n = 310) . | Unrelated (n = 331) . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | N . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | |||||

| HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | |||

| WBC count at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| < 30 000/μL | 224 | 1.00 | — | 230 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 30 000/μL or more at diagnosis | 86 | 1.21 (0.63-2.34) | .57 | — | 101 | 0.79 (0.48-1.30) | .35 | — | ||

| Lineage | ||||||||||

| B | 218 | 1.00 | — | 203 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| T | 50 | 1.25 (0.41-3.81) | .53 | — | 54 | 0.62 (0.29-1.38) | .17 | — | ||

| Other | 42 | 0.87 (0.34-2.26) | .78 | — | 74 | 1.08 (0.65-1.81) | .76 | — | ||

| Karyotype | ||||||||||

| Normal | 193 | 1.00 | — | 208 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| t(4;11) or t(1;19) | 21 | 0.77 (0.16-3.17) | .73 | — | 11 | 1.03 (0.25-4.30) | .63 | 1.11 (0.27-4.64) | .57 | |

| Other (no t(9;22)) | 96 | 0.92 (0.47-1.81) | .81 | — | 112 | 1.47 (0.94-2.29) | .09 | 1.67 (1.06-2.64) | .03 | |

| JALSG risk stratification | ||||||||||

| Low | 39 | 1.00 | — | 45 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Intermediate | 163 | 1.85 (0.86-3.97) | .12 | — | 192 | 1.01 (0.62-1.65) | .96 | — | ||

| High | 108 | 2.82 (1.09-7.31) | .03 | — | 94 | 1.03 (0.50-2.10) | .94 | — | ||

| Age at allo-SCT | ||||||||||

| < 45 y old | 255 | 1.00 | — | 281 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 45 y old or older at allo-SCT | 55 | 3.90 (2.09-7.25) | < .0001 | 3.90 (2.09-7.25) | < .0001 | 50 | 1.26 (0.72-2.20) | .42 | ||

| HLA | ||||||||||

| Match | 285 | 1.00 | — | 192 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Mismatch | 25 | 1.64 (0.64-4.18) | .30 | — | 139 | 1.69 (1.10-2.60) | .02 | 1.69 (1.10-2.61) | .02 | |

| Stem cell source | ||||||||||

| Bone marrow | 212 | 1.00 | — | — | ||||||

| Peripheral blood | 98 | 1.75 (0.94-3.28) | .08 | — | — | |||||

| Time from diagnosis to allo-SCT | ||||||||||

| 6 mo or longer | 169 | 1.00 | — | 23 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| < 6 mo | 141 | 1.64 (0.87-3.11) | .13 | — | 308 | 0.31 (0.08-1.25) | .10 | — | ||

| < 10 mo | 278 | 1.00 | — | 166 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| 10 mo or longer | 32 | 1.07 (0.42-2.72) | .89 | — | 165 | 1.90 (1.21-2.99) | .01 | 1.98 (1.26-3.13) | .003 | |

| Preparative regimen | ||||||||||

| Non-TBI regimens | 25 | 1.00 | — | 12 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| TBI regimens | 285 | 0.63 (0.25-1.61) | .34 | — | 319 | 0.67 (0.25-1.85) | .44 | — | ||

| GVHD prophylaxis | ||||||||||

| Cyclosporine A with or without other | 283 | 1.00 | — | 171 | 1.00 | — | ||||

| Tacrolimus with or without other | 27 | 1.66 (0.65-3.80) | .29 | — | 160 | 1.33 (0.86-2.05) | .52 | — | ||

HR indicates hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; WBC, white blood cell; —, not applicable; and TBI, total body irradiation.

Acute and chronic GVHD among patients transplanted in CR1

The cumulative incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD was significantly higher in patients who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT compared with those who underwent a related allo-SCT (related vs unrelated: 30% vs 42% at day 100; P = .0003). The cumulative incidence of grade III-IV acute GVHD was significantly higher in patients who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT compared with those who underwent a related allo-SCT (related vs unrelated: 7% vs 16% at day 100; P = .0006).

Among evaluable patients who survived at least 100 days after allo-SCT, no significant difference was observed between related and unrelated allo-SCTs in the incidence of chronic GVHD (related vs unrelated: 41% vs 41% at 2 years; P = .76). Extensive disease was observed in 60 (55%) of 109 with chronic GVHD after related allo-SCT and in 80 (74%) of 118 after unrelated allo-SCT (P = .048).

Causes of death among patients transplanted in CR1

Although relapse was the leading cause of death in both related and unrelated allo-SCTs, the proportion of relapse was significantly lower in those transplanted from unrelated donors (P = .01). Infection, GVHD, and organ failure were the major causes of NRM, and the incidence of interstitial pneumonia was higher in patients transplanted from unrelated donors (P = .06; Table 5).

Causes of death among patients transplanted in CR1, according to donor type

| . | Related (n = 310) . | Unrelated (n = 331) . | P . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | n . | % . | ||

| Relapse | 44 | 44 | 32 | 26 | .01 |

| Infection | 12 | 12 | 23 | 19 | .20 |

| Organ failure | 12 | 12 | 17 | 14 | .83 |

| GVHD | 9 | 8.9 | 16 | 13 | .40 |

| Interstitial pneumonia | 5 | 5.0 | 15 | 12 | .06 |

| Hemorrhage | 3 | 3.0 | 6 | 5.0 | .52 |

| Graft failure | 2 | 2.0 | 3 | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| ARDS | 1 | 1.0 | 3 | 2.5 | .63 |

| Other | 8 | 7.9 | 6 | 5.0 | .42 |

| Unknown | 5 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 | .02 |

| Total | 101 | 100 | 121 | 100 | |

| . | Related (n = 310) . | Unrelated (n = 331) . | P . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | n . | % . | ||

| Relapse | 44 | 44 | 32 | 26 | .01 |

| Infection | 12 | 12 | 23 | 19 | .20 |

| Organ failure | 12 | 12 | 17 | 14 | .83 |

| GVHD | 9 | 8.9 | 16 | 13 | .40 |

| Interstitial pneumonia | 5 | 5.0 | 15 | 12 | .06 |

| Hemorrhage | 3 | 3.0 | 6 | 5.0 | .52 |

| Graft failure | 2 | 2.0 | 3 | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| ARDS | 1 | 1.0 | 3 | 2.5 | .63 |

| Other | 8 | 7.9 | 6 | 5.0 | .42 |

| Unknown | 5 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 | .02 |

| Total | 101 | 100 | 121 | 100 | |

ARDS indicates acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Discussion

This study reports the largest series of adult Ph− ALL patients who underwent allo-SCT. There was no significant survival difference between related and unrelated allo-SCTs in any disease stage. Among patients who underwent a related allo-SCT in CR1, a shorter interval from diagnosis to allo-SCT was associated with relapse, and age at allo-SCT was associated with NRM. On the other hand, among patients who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT, abnormal karyotype was associated with both relapse and NRM, and a longer interval from diagnosis to allo-SCT and HLA mismatch were associated with NRM. These results indicated that factors affecting transplantation outcomes were different according to donor type.

In our study, unrelated allo-SCT resulted in OS rates similar to those from related allo-SCT, which was compatible with the result of one prospective study for standard-risk hematologic malignancies.14 The rates of OS, relapse, and NRM among patients who underwent a related allo-SCT in CR1 were 65%, 32%, and 14%, respectively, which were compatible with those observed in the United Kingdom Medical Research Council UKALL XII/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group E2993 trial (53%, 24%, and 18%, respectively).3 Some patients were transplanted from a 1-locus mismatched related donor because it was reported that the outcome of allo-SCT from a 1 locus-mismatched related donor was similar to that of matched unrelated allo-SCT in the Japanese population.15 On the other hand, the rates of OS, relapse, and NRM among patients who underwent an unrelated allo-SCT were 62%, 22%, and 27%, respectively, which were better than those reported from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (39%, 20%, and 42%, respectively).4 These differences in NRM could be explained by the lower incidence of acute GVHD in our population, which possibly resulted from the genetic homogeneity in the Japanese population.16,17 Interestingly, abnormal karyotype was associated with NRM. This could be explained by the possibility that patients with abnormal karyotype received intensive chemotherapy before allo-SCT because of persistent minimal residual disease, which might result in increased NRM rates. Another possibility is that rapid taper of immunosuppressive treatment might also cause GVHD leading to NRM.

In this study, NRM rates were higher in unrelated allo-SCT compared with related allo-SCT, whereas comparable NRM rates were reported in some recent reports,18 suggesting that NRM rates after unrelated allo-SCT could be reduced with further efforts, such as better HLA matching. Because HLA-C was not routinely typed before 2003, most of the HLA-C data in this study were examined retrospectively, revealing that considerable numbers of patients had received class I allele-mismatched unrelated allo-SCT. Better HLA matching might reduce NRM after unrelated allo-SCT in the future. Although slower hematopoietic recovery after bone marrow transplantation compared with peripheral blood stem cell transplantation might affect the timing of deaths, there was no statistical difference in early mortality between the grafts (data not shown).

There was no statistical difference in the incidence of chronic GVHD between related and unrelated allo-SCTs, although acute GVHD was observed more frequently in unrelated allo-SCT. This was compatible with a past report in which the incidence of chronic GVHD was similar between related and unrelated allo-SCTs, whereas acute GVHD was observed more frequently in related allo-SCT.14

It was noteworthy that the interval from diagnosis to allo-SCT revealed a different effect on related and unrelated allo-SCTs. In Japanese clinical practice, the JALSG protocols have been common, where 1.5-month induction chemotherapy was followed by 6-month consolidation chemotherapy and 16-month maintenance chemotherapy.8 Therefore, a shorter interval from diagnosis to allo-SCT, which was more common in related cases, might result in insufficient consolidation chemotherapy and worse survival because of increased relapse rates in related allo-SCT. Alternatively, effects from insufficient consolidation chemotherapy might be more prominent in related allo-SCT because graft-versus-leukemia effects might be weaker after related allo-SCT than unrelated allo-SCT.19 On the other hand, a longer interval from diagnosis to allo-SCT, which was more common in unrelated cases, might result in the cumulative toxic sequelae of chemotherapy responsible for interstitial pneumonia indicated in the past reports.20-25 Because the JALSG protocols do not define the timing of allo-SCT, it is possible that chemotherapy before allo-SCT might be prolonged because of persistent minimal residual disease. However, we could not confirm this because there were no data concerning minimal residual disease in the registry database.

Although we mainly focused on patients in CR1, our results also indicated that some, but not all, patients with refractory disease could be rescued by allo-SCT. These patients could not have survived long with chemotherapy alone, and complete unresponsiveness, even to allo-SCT, was often assumed. These results were compatible with some reports showing that long-term survival could be achieved for patients receiving allo-SCT, even in refractory disease.26-28

Our study has several limitations. First, there might be some selection biases between related and unrelated allo-SCTs. It was possible that eligibility was more stringent in patients who received unrelated allo-SCT, and they might have had better pretransplantation conditions. Second, a time-censoring effect might impact the outcome. The longer interval from diagnosis to unrelated allo-SCT eliminates the effect of patients who die during that period. This bias might improve the outcome of unrelated allo-SCT. Third, we could not make the comparison between chemotherapy and allo-SCT in this study.

The time-censoring effect could be the major bias in this study, which resulted in lower relapse rates, especially in patients transplanted from unrelated donors. We tried to correct this bias by the previously described method.29 In the JALSG ALL study, it was reported that approximately 80% and 75% of patients were alive 6 months and 10 months after enrollment, respectively.8 Because 6 months and 10 months were the median interval from diagnosis to related and unrelated allo-SCTs, respectively, a crude way to apply a correction factor for the survival seen in our study is to lower the survival estimate at any given time point by 20% for related allo-SCT and 25% for unrelated allo-SCT, respectively. Thus, the corrected OS rates at 4 years were 52% ± 5% for related allo-SCT and 47% ± 4% for unrelated allo-SCT, which showed no statistical difference between related and unrelated allo-SCTs. Time-censoring effects would not change the results.

The change of transplantation indication for adolescents through the observation period might affect the outcome. In the JALSG protocol ALL202 (from September 2002), we treated patients less than 25 years old with a similar protocol performed for pediatric patients. Because allo-SCT was recommended only for high-risk patients, such as those with t(4;11) or MLL-rearrangement in the pediatric protocol, the outcome of young patients might be affected by the difference in the indication for allo-SCT between pediatric and adult protocols after 2002. However, the effect of this small population would not be so large.

In conclusion, comparable survival rates were observed between adult Ph− ALL patients who underwent related and unrelated allo-SCTs in CR1, although relapse rates, incidences of NRM, and risk factors for transplantation outcomes were different between them. Better outcomes could be achieved by performing allo-SCT at an appropriate timing and HLA compatibility according to donor type.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the staff of the participating institutions of the Japan Society for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation and the Japan Donor Marrow Program as well as Dr T. Kawase for the data collection of JMDP.

This work was supported in part by the Japan Leukemia Research Fund (S.N.) and in part by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan (Grant-in-Aid) (K.M.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.N., Y.I., and K.M. designed the research and wrote the manuscript; S.N. and Y.I. performed the statistical analysis and interpreted the data; H.S., M. Kurokawa, H.I., H.O., T.F., Y.O., N.K., M. Kasai., T.M., K.I., T.Y., M.O., and K.M. provided the patient data; and K.K., Y.M., R.S., and Y.A. collected the patient data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Satoshi Nishiwaki, Department of Hematology, Japanese Red Cross Nagoya First Hospital, 3-35 Michishita-cho, Nakamura-ku, Nagoya, Aichi 453-8511, Japan; e-mail: n-3104@tf7.so-net.ne.jp.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal