Abstract

Gfi-1B is a transcriptional repressor that is crucial for erythroid differentiation: inactivation of the GFI1B gene in mice leads to embryonic death due to failure to produce differentiated red cells. Accordingly, GFI1B expression is tightly regulated during erythropoiesis, but the mechanisms involved in such regulation remain partially understood. We here identify HMGB2, a high-mobility group HMG protein, as a key regulator of GFI1B transcription. HMGB2 binds to the GFI1B promoter in vivo and up-regulates its trans-activation most likely by enhancing the binding of Oct-1 and, to a lesser extent, of GATA-1 and NF-Y to the GFI1B promoter. HMGB2 expression increases during erythroid differentiation concomitantly to the increase of GfI1B transcription. Importantly, knockdown of HMGB2 in immature hematopoietic progenitor cells leads to decreased Gfi-1B expression and impairs their erythroid differentiation. We propose that HMGB2 potentiates GATA-1–dependent transcription of GFI1B by Oct-1 and thereby controls erythroid differentiation.

Introduction

Gfi-1 and Gfi-1B are members of the Gfi zinc-finger transcriptional repressor family, whose structure is characterized by an N-terminal repressor domain called SNAG and 6 C-terminal C2H2 zinc fingers.1 Gfi-1 and Gfi-1B are differentially expressed in hematopoietic cells. Gfi-1 is expressed in immature progenitors and highly expressed in granulocytes,2,3 whereas Gfi-1B expression is restricted to erythroid and megakaryocytic cells.4,5 Analysis of Gfi-1B/green fluorescent protein knock-in mice has shown that Gfi-1B expression is dynamically regulated during murine erythropoiesis.4 Deletion of the Gfi-1 gene in mice provokes a severe disturbance of hematopoietic stem cell function due to excessive cycling and severe neutropenia.2,6,7 GFI1B–deficient mice are not viable beyond embryonic day 14.5 and fail to produce definitive enucleated red cells.8 Accordingly, Gfi-1B overexpression in erythroid progenitors strongly disturbs erythroid maturation.5,9 Gfi-1 and Gfi-1B bind to the same consensus DNA sequence TAAATCAC(A/T)GCA,1,10,11 and knock-in mice in which the Gfi-1 coding region was replaced by GFI1B showed that Gfi-1B can replace Gfi-1 in the regulation of hematopoiesis.12

The mechanisms accounting for the GFI1B transcriptional regulation are not fully understood. The GFI1B promoter was cloned and an erythroid-specific promoter region was characterized in K562 cells. GATA-1 and NF-YA cooperate to activate Gfi-1B transcription.13 Recently, chromatin regulatory proteins (Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1 [LSD1], Co-RE1-Silencing Transcription factor [CoREST], and Histone deacetylase [HDAC]) have been suggested to mediate transcriptional repression of Gfi-1B target genes.14 Overexpression of Gfi-1B in NIH3T3 or undifferentiated K562 cells,15 as well as in the spleen or thymus of vav-GFI1B transgenic mice,16 provided evidence of an autoregulation mechanism of GFI1B transcription. We have shown that Gfi-1B does not repress its own transcription during erythroid differentiation. Indeed, GFI1B promoter remains associated with a transcriptionally active chromatin configuration throughout erythroid differentiation as highlighted by an increase in histone H3 acetylation and concomitant release of the corepressors LSD1 and CoREST.17 Besides GATA-1, few activators of the GFI1B transcription have been identified.

In this report, we identify a high-mobility group box (HMGB) protein, HMGB2, associated with the GFI1B promoter and investigate the function of HMGB2 in the regulation of Gfi-1B expression during erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation. HMGB proteins, 1 of the 3 classes of high-mobility group (HMG) proteins, are abundant nonhistone nuclear proteins that associate with chromatin. HMGB proteins consist of an acidic C-terminal tail of variable length and of 2 tandem HMG boxes, the A and B domains, which bind to the minor groove of DNA. It has been proposed that HMGB proteins can act as architectural facilitators in the assembly of nucleoprotein complexes by bending DNA.18,19 In addition, HMGB proteins were also shown to interact with transcription factors such as p53,20 HoxD9,21 Oct-1/2,22 and NF-Y.23 These interactions eventually lead to the recruitment of HMGB to specific sites of the genome where it locally modulates the association of transcription factors to their cognate DNA-binding sites.

We found that Gfi-1B and HMGB2 follow the same kinetics of expression during erythroid differentiation. HMGB2 binds in vivo to the GFI1B promoter and up-regulates its activity by increasing Oct-1 and, to a lesser extent, GATA-1 and NF-Y binding. Finally, we show that knockdown of HMGB2 in CD34+ cells severely impedes their erythroid and megakaryocytic potential.

Methods

Cell culture

Human UT-7 cells were maintained in α-minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine and 2 U/mL erythropoietin (EPO). Human umbilical cord blood samples were collected from normal full-term deliveries, after informed consent of the mothers according to the approved institutional guidelines of Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP) following the Declaration of Helsinki. After isolation of mononuclear cells by density gradient separation, CD34+ cells were purified using magnetic bead separation (StemCell Technologies). CD34+ cells (purity ≥ 95%) were used immediately or after storage in liquid nitrogen. CD34+ cells were maintained for 5 days in serum-free Stem Span medium (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 25 ng/mL stem cell factor (SCF), 10 ng/mL interleukin-3 (IL-3), 10−6 M dexamethasone, and 2 U/mL EPO. Then, cells were induced to differentiate for 5 to 6 days in Stem Span medium supplemented with 25 ng/mL SCF and 2 U/mL EPO. Recombinant human EPO was a gift from Dr M. Brandt (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Others cytokines were purchased from Promocell Bioscience Alive GMBH.

Cell transduction

Five pLKO.1 lentiviral shRNAs against human HMGB2 (from Open Biosystems) were tested for their ability to deplete HMGB2 protein in erythroid cells. Two of 5 were very efficient at knocking down HMGB2. These 2 lentiviral vectors had the same effect on erythroid differentiation and were used indifferently. CD34+ cells were infected twice (D1 and D2 during the amplification step) with lentiviral vectors and, 48 hours after infection, puromycin (1 μg/mL) was added to the medium. UT-7 cells were infected only once and selected with puromycin. The effects of the shRNA on HMGB2 protein level was tested 48 hours after the beginning of the puromycin selection by Western blot. As control vectors we used a nontargeting scramble shRNA with a green fluorescent protein sequence or a vector containing only the puromycin-resistant gene. The 2 control vectors gave the same results. We showed only results with puromycin-resistant vector.

Colony-forming unit assays for cell progenitor quantification

For myeloid colony assays, CD34+ were plated in duplicate in Methocult H4100 methylcellulose medium (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 125 ng/mL SCF, 50 ng/mL IL-3, 50 ng/mL IL-6, and 2 UI/mL EPO for 6 (erythroid colony-forming unit [CFU-E]) or 10 to 12 (erythroid burst-forming unit [BFU-E]) days. Colonies were scored under microscope. To evaluate the differentiation status of the cells, 3 to 5 colonies were collected and pooled to cytospin and stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa. For megakaryocytic progenitors, CD34+ cells were plated in H4230 Megacult-C medium (StemCell Technologies) containing 50 ng/mL recombinant human thrombopoietin (TPO), 10 ng/mL IL-6 and 10 ng/mL IL-3 for 10 to 12 days and then, dehydrated, fixed, stained with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antibodies, and revealed by alkaline phosphatase reaction using a staining detection kit (H-4962; StemCell Technologies). Colony score was also made under microscope.

Plasmid constructs and site-directed mutagenesis

The human wild-type GFI1B erythroid-specific promoter (−145/+19)–luciferase construct was a gift from Dr Chang (Taipei, Taiwan). Mutations on the GFI1B promoter were generated using QuikChange Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). Gfi-1/Gfi-1B–binding sites (AATC at −59/−56, −54/−51 and −47/−44 within site 2) that were also GATA-binding sites (GATT reverse orientation) were simultaneously mutated into GGTC. GATA-binding site (GATA at −132/−129 within site 1) was mutated into GACC. AAAT sites (Oct-1 homeodomain–binding site) at −125/−122 (site 1) and −63/−60 (site 2) were mutated simultaneously or independently into ACGG.

Luciferase assays

HeLa cells were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The total amount of DNA in each transfection was kept constant at 625 ng (250 ng of promoter-luciferase construct and 125 ng of each expression plasmid) and 10 ng of internal control plasmid (pRL-TK; Promega). Expression plasmid encoding GATA-1 was described and constructed by Kadri et al.24 The expression plasmid encoding Oct-1 was already described25 and the expression plasmids encoding NF-YA were from M. L. Vignais (Montpellier, France) and R. Mantovani (Milan, Italy). The expression plasmid encoding HMGB2 was generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from pEGP-N1-HMGB226 using primers 5′-GCCACCATGGGTAAAGGAGA-3′ and 5′-TTCTTCATCTTCAT-CCTCTTCCTC-3′. The PCR product was inserted into pCDNA3.1/V5-His TOPO. This plasmid pCDNA3.1/V5-His–HMGB2 encodes human HMGB2 fused to the V5 and 6His Tag. After 24 to 30 hours, firefly luciferase activity was measured according to the manufacturer's instructions (Dual Luciferase Assay System; Promega), and individual transfections were normalized by measurement of Renilla luciferase activity (pRL-TK; Promega) and pGL2-luciferase activity.

Nuclear extract preparation and biotin-streptavidin oligonucleotide pull-down assays

For nuclear extract preparation, cells were washed once with PBS and incubated for 10 minutes at 4°C in buffer A (10mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.6, 3mM MgCl2, 10mM KCl, 5% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40) containing 1mM Na2VO4, 20mM NaF, 1mM sodium pyrophosphate, 25mM β-glycerophosphate, and proteinase inhibitors (Roche). After centrifugation, nuclear pellets were resuspended in buffer A containing 300mM KCl. For oligonucleotide pull-down assays, complexes from 107 cell nuclear extracts were precipitated by addition of 1, 2, or 4 μg of double-strand biotin-labeled oligonucleotide at 4°C for 1 hour. DNA-protein complexes were then pelleted using streptavidin-agarose beads (Amersham Biosciences). Beads were then washed 3 times with buffer A and resuspended in 1× Laemmli buffer. The following biotinylated oligonucleotides were used: wild-type site 1 oligo, biotin-5′-CCTGGAAAGTTTTGATAAGCAAATACGGCT-3′, mutated site 1 oligo, biotin-5′-CCTGGAAAGTTTTGACCAGCAAATACGGCT-3′, wild-type site 2 oligo, biotin-5′-GACACAAATAATCAGATTGAAAATCAGGGAG-3′, and mutated site 2, biotin-5′-GACACAAATGGTCAGACCGAAGGTC-AGGGAG-3′.

Western blot analysis and antibodies

Samples were subjected to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell). Filters were blocked overnight in 5% skimmed milk Tris-buffered saline (TBS)–0.05% Tween 20 and incubated with the appropriate antibody. Membranes were washed 4 times in TBS-Tween 20 and incubated for 1 hour with the appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The primary antibodies used were as follows: GATA-1 N1 (sc-266; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); HMGB2 (556529; BD PharMingen); Oct-1 C-21 (sc-232; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); NF-YA (sc-10779; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); and β-actin (A5441; Sigma). Serum against Gfi-1B was prepared in the laboratory.17 The horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies were as follows: anti–rat (sc-2006; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–rabbit (7074; Cell Signaling) and anti–mouse (7076; Cell Signaling).

ChIP assays

Cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature before termination with 0.125M glycine. Cells were then lysed in chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) buffer (1% SDS, 10mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 50mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1) and cross-linked chromatin was sonicated to obtain DNA fragments of 300 to 800 bp. Immunoprecipitations were performed following the Upstate protocol.17 Antibodies against HMGB2, NF-YA, and Oct-1 used for ChIP assays were the same as for Western blot. GATA-1 ChIP was performed with the antibody GATA-1 C20 (sc-1233; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For analysis of histone modifications, acetyl Lys9/14-H3 (06-599; Upstate), dimethyl Lys4-H3 (07-030; Upstate), and trimethyl Lys27-H3 (07-449; Upstate) were used. The corresponding normal rabbit, goat, or mouse immunoglobulins G (IgGs; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used as control. The immunoprecipitated DNA was used for PCR with the following thermal cycling program: 95°C for 5 minutes, 40 cycles of 30 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 60°C, and 45 seconds at 72°C, followed by a 5-minute extension time at 72°C. The GFI1B promoter sequence was amplified with the following primers: 5′-GAATTCGAAGTCTTGTGTCC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTGTGTTTTTCCTCTTCTGT-3′ (antisense) and the β2microglobulin promoter, used as control, with the following primers: 5′-CCAGTCTAGTGCATGCCTTCTTAA-3′ (sense) and 5′-CAAGCCAGCGACGCAGT-3′ (antisense).

Mass spectrometry

Proteins bound on oligonucleotides were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. After Coomassie staining, the protein band with a 25-kDa apparent molecular mass was cut and destained. The proteins in the gel slice were reduced with dithiothreitol, alkylated with iodoacetamid, and digested with trypsin. Peptides were extracted with a water/acetonitrile/trifluoracetic acid mixture (50:50:0.1) and cleaned using C18 ZipTips (Millipore).

Results

HMGB2 is associated with GFI1B promoter oligonucleotides in vitro

We have shown that Gfi-1B remains highly expressed all along erythroid differentiation.17 To identify transcriptional regulators other than GATA proteins responsible for sustained GFI1B promoter activity in erythroid cells, we performed oligo pull-down experiments using oligonucleotides corresponding to the described transcriptionally active part of the GFI1B promoter15 (Figure 1A) followed by mass-spectroscopy analysis. We thereby identified HMGB2 as a major GFI1B promoter-binding protein. Analysis using the Mascot search program28 showed that 12 peptides matched with HMGB2 sequence (Figure 1B and supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). HMGB2 binding increased when enhanced amounts of oligonucleotides were used (Figure 1A). We thus investigated the function of HMGB2 in the regulation of Gfi-1B expression during erythroid differentiation.

HMGB2 is associated with oligonucleotide corresponding to the GFI1B promoter. (A) Proteins bound to GFI1B promoter oligonucleotide were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. After Coomassie staining, the protein band with a 25-kDa apparent molecular weight was cut and analyzed by mass spectrometry. (B) Extracted peptides were analyzed by mass spectroscopy using a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Voyager DEPro; Applied Biosystems). Monoisotopic mass list was used to search the Swiss-Prot database27 for human proteins using the Mascot search engine. (C) Schematic representation of the GFI1B promoter. Two specific regulatory regions were indicated “site 1” (−138 to −116) and “site 2” (−69 to −37). The 2 putative Oct-1–binding sites identified in this study and the NF-Y–binding site were indicated. (D) GATA-1, Oct-1, NF-Y, and HMGB2 association with oligonucleotides corresponding to the GFI1B promoter. Oligo pull-down assays were performed with cell lysates from differentiated erythroid cells harvested 3 days after induction of erythroid differentiation (E3) of CD34+ cells. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with increasing amount of oligonucleotides representing wild-type (indicated above the lanes by black wedges) or mutated site 1 or site 2 of the GFI1B promoter. Proteins bound to the DNA template were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against GATA-1, Oct-1, NF-YA, or HMGB2. The results shown on this figure are representative of 4 experiments.

HMGB2 is associated with oligonucleotide corresponding to the GFI1B promoter. (A) Proteins bound to GFI1B promoter oligonucleotide were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. After Coomassie staining, the protein band with a 25-kDa apparent molecular weight was cut and analyzed by mass spectrometry. (B) Extracted peptides were analyzed by mass spectroscopy using a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Voyager DEPro; Applied Biosystems). Monoisotopic mass list was used to search the Swiss-Prot database27 for human proteins using the Mascot search engine. (C) Schematic representation of the GFI1B promoter. Two specific regulatory regions were indicated “site 1” (−138 to −116) and “site 2” (−69 to −37). The 2 putative Oct-1–binding sites identified in this study and the NF-Y–binding site were indicated. (D) GATA-1, Oct-1, NF-Y, and HMGB2 association with oligonucleotides corresponding to the GFI1B promoter. Oligo pull-down assays were performed with cell lysates from differentiated erythroid cells harvested 3 days after induction of erythroid differentiation (E3) of CD34+ cells. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with increasing amount of oligonucleotides representing wild-type (indicated above the lanes by black wedges) or mutated site 1 or site 2 of the GFI1B promoter. Proteins bound to the DNA template were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against GATA-1, Oct-1, NF-YA, or HMGB2. The results shown on this figure are representative of 4 experiments.

Erythroid-specific Gfi-1B expression relies on 2 main sites on its promoter that are both targeted by the GATA-1 transcription activator (sites 1 and 2) and separated by an NF-Y–binding site13,15,17 (Figure 1C). Interestingly, sequence analysis showed the presence of 2 Oct putative binding sequences at both of these sites (Figure 1C). Indeed, HMGB2 was described as binding to DNA without any sequence specificity but potentiating the activity of other transcription factors such as Oct-122 and NF-Y.23 We thus investigated whether Oct-1, NF-YA, and HMGB2 associated with sites 1 and 2 at the GFI1B promoter in primary erythroid cells. CD34+ cells were isolated from cord blood and amplified in a 2-phase culture system: a 5-day amplification step (D1-D5) in the presence of SCF, IL-3, EPO, and dexamethasone followed by a 5-day differentiation step (E0-E5) in the presence of SCF and EPO. DNA affinity precipitation experiments were carried out using differentiated erythroid cells harvested 4 days after induction of erythroid differentiation (E4) and an increasing amount of biotinylated oligonucleotides that contain GFI1B promoter site 1 or 2 (Figure 1D). We found that GATA-1 associated with similar affinities to site 1 and 2. By contrast, Oct-1 and NF-YA associated to site 1 with a higher affinity compared with site 2. HMGB2 bound similarly to both oligonucleotides (Figure 1D). Mutations on the GATA-binding sites contained within the site 1 and mutations on the 3 Gfi-1/Gfi-1B contained within the site 2 of the GFI1B promoter abolished the association of GATA-1, NF-YA, and Oct-1. However, these mutations did not modify the binding of HMGB2 to both sites, confirming that GATA-1, NF-YA, and Oct-1 bindings are sequence specific, whereas HMGB2 binding is not. Furthermore, this result also shows that HMGB2 binds to sites 1 and 2 in the absence of Oct-1, NF-YA, or GATA-1. We conclude that HMGB2 together with GATA-1, NF-Y, and Oct-1 bind as a protein complex to the GFI1B promoter in erythroid cells. The high affinity of HMGB2 for DNA was already described.29 However, we studied the binding of HMGB2 to DNA sequences of different promoters or intergenic regions by oligo pull-down and ChIP assays and confirmed that HMGB2 binds to DNA with no sequence specificity (supplemental Figure 2C).

HMGB2 potentiates GATA-1–dependent GFI1B transcription in the presence of Oct-1

Having shown that HMGB2 binds to the GFI1B promoter, we investigated whether it modifies its transcriptional activity by performing luciferase gene reporter experiments. Transfection of the GFI1B promoter construct into HeLa cells together with a GATA-1 expression plasmid increased its activity by 4-fold, as previously described.13 This effect was amplified when cotransfecting both GATA-1 and Oct-1 (358 ± 33 vs 503 ± 130, P < .05), whereas transfection of Oct-1 alone or in association with HMGB2 did not have any impact on GFI1B promoter activity. Interestingly, whereas cotransfection of HMGB2 with GATA-1 slightly affected GFI1B transcription, cotransfection of HMGB2 together with GATA-1 and Oct-1 strongly increased the GFI1B promoter activity (362 ± 59 vs 895 ± 144, P < .001; Figure 2A). By contrast, cotransfection of HMGB2 together with GATA-1 and NF-YA did not significantly increase the GFI1B promoter activity (GATA + HMGB2: 503 ± 129 vs GATA + HMGB2 + NF-YA: 546 ± 132). Thus, in in vitro transient transfection experiments, HMGB2 increases the up-regulation of GATA-1–dependent GFI1B transcription by Oct-1 but not by NF-Y.

HMGB2 stimulates GFI1B promoter activity through GATA-1 and Oct-1 binding to the GFI1B promoter in vitro. (A) Effects of HMGB2 on GFI1B promoter activity. Gfi-1B luciferase reporter construct was transfected into HeLa cells together with GATA-1, Oct-1, NF-Y, or HMGB2 expression vectors. Thirty hours after transfection, luciferase activity was evaluated. Individual transfection was normalized by measurement of Renilla luciferase activity (pRL-TK; Promega) and pGL2-luciferase activity. Experiments were performed with shControl-transduced (shControl) or shHMGB2-transduced (shHMGB2) cells. Results are means ± SD of 4 independent experiments; *P < .05 and ***P < .001. (B) Effects of mutations at GATA or Oct-1–putative binding sites at the GFI1B promoter. The construct bearing the GFI1B promoter sequence was mutated at the putative GATA-binding (site 1) or Oct-1–binding (sites 1 and 2) sites (mutations were indicated at the bottom of the figure by a cross on the schematic representation of the GFI1B promoter). Wild-type or mutated reporter constructs were transfected into HeLa cells together with GATA-1 alone or with GATA-1, Oct-1, and HMGB2 expression vectors. Luciferase activity was measured 30 hours after transfection. Results are means ± SD of 4 independent experiments; *P < .02 and **P < .003.

HMGB2 stimulates GFI1B promoter activity through GATA-1 and Oct-1 binding to the GFI1B promoter in vitro. (A) Effects of HMGB2 on GFI1B promoter activity. Gfi-1B luciferase reporter construct was transfected into HeLa cells together with GATA-1, Oct-1, NF-Y, or HMGB2 expression vectors. Thirty hours after transfection, luciferase activity was evaluated. Individual transfection was normalized by measurement of Renilla luciferase activity (pRL-TK; Promega) and pGL2-luciferase activity. Experiments were performed with shControl-transduced (shControl) or shHMGB2-transduced (shHMGB2) cells. Results are means ± SD of 4 independent experiments; *P < .05 and ***P < .001. (B) Effects of mutations at GATA or Oct-1–putative binding sites at the GFI1B promoter. The construct bearing the GFI1B promoter sequence was mutated at the putative GATA-binding (site 1) or Oct-1–binding (sites 1 and 2) sites (mutations were indicated at the bottom of the figure by a cross on the schematic representation of the GFI1B promoter). Wild-type or mutated reporter constructs were transfected into HeLa cells together with GATA-1 alone or with GATA-1, Oct-1, and HMGB2 expression vectors. Luciferase activity was measured 30 hours after transfection. Results are means ± SD of 4 independent experiments; *P < .02 and **P < .003.

To confirm the specificity of the GATA-1 plus Oct-1–mediated GFI1B transactivation by HMGB2, we performed equivalent experiments in cells knocked down for HMGB2. Both endogenous and exogenous HMGB2 were efficiently depleted when transducing the cells with lentiviral vectors expressing HMGB2-specific shRNA (data not shown). Importantly, the potentiation of GFI1B promoter activity observed when cotransfecting HMGB2 with GATA-1 and Oct-1 factors was lost upon HMGB2 depletion (Figure 2A). Therefore, HMGB2 strongly enhances the activation of GFI1B transcription by GATA-1 when Oct-1 is present.

To identify the regions within the GFI1B promoter required for potentiation of GFI1B transcription by HMGB2, we mutated the GATA-binding sites (site 1 and 2) as well as the 2 putative Oct-binding sites (sites 1 and 2) at the GFI1B promoter. Because simultaneous mutations of the 3 AATC sites at the site 2 of the GFI1B promoter abolished completely the GATA-1–mediated transactivation of the GFI1B promoter (data not shown and Huang et al15 ), it is irrelevant to analyze the effect of HMGB2 on GATA-mediated transactivation of this mutated promoter. Mutation of the GATA site (site 1) abolished the potentiating effect of HMGB2 on GFI1B promoter transactivation (Figure 2B). In contrast, mutation of only 1 of the 2 Oct-binding sites had slightly significant (930 ± 180 vs 1580 ± 260, P < .03) or no significant (1285 ± 210 vs 1580 ± 260, P = .2) effect. Strikingly, HMGB2 did not modify GFI1B promoter activity when both Oct-binding sites were mutated. This result is in full agreement with our finding that Oct-1 is indeed required for the potentiation of GATA-1–dependent transactivation by HMGB2. We therefore conclude that HMGB2 potentiates the ability of Oct-1 to enhance GATA-1–dependent transcription of GFI1B.

HMGB2 promotes the binding of Oct-1 to the GFI1B promoter in human erythroid cells

So far, we have shown that HMGB2 increases the up-regulation of GATA-1–dependent GFI1B transcription by Oct-1. We thus raised the hypothesis that HMGB2 increases the binding of Oct-1 to the GFI1B promoter in erythroid cells. To test this hypothesis, we compared the ability of Oct-1 to associate with the oligonucleotide corresponding to the GFI1B promoter site 1 and site 2 in the presence or in the absence of HMGB2. Cellular extracts from UT-7 cells transduced with a shControl or with a shHMGB2 were used for these experiments (Figure 3A). Western blot analysis of bound proteins showed that Oct-1 and NF-Y associate with site 1 of the GFI1B promoter. Oct-1—and not NF-YA—binding to site 2 was observed only during overexposure (data not shown). Oct-1 and NF-YA did not bind to the GFI1B promoter when mutating the GATA-binding site (Figure 3A). These results confirm our previous results described in Figure 1D showing that GATA is required for Oct-1 and NF-Y association. Interestingly, the association of Oct-1—but not the association of NF-YA—with site 1 slightly decreased in the absence of HMGB2. Thus, HMGB2 increases the binding of Oct-1 to the promoter of the GFI1B gene in vitro.

HMGB2 increases Oct-1 binding to the GFI1B promoter in vitro and in vivo. (A) GATA-1, Oct-1, NF-YA, and HMGB2 binding to the GFI1B promoter in vitro in the presence or absence of HMGB2. Oligonucleotide corresponding to site 1 or site 2 of the GFI1B promoter was incubated with cell lysates from erythroid UT-7 cells. The GATA site of the site 1 and the 3 Gfi-1/Gfi-1B–binding sites of the site 2 oligonucleotides (that bind GATA-1) were mutated when indicated. Cell lysates from UT7 cells infected with shControl or shHMGB2 lentiviruses were used. Total cell extracts were shown (input). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) In vivo binding of HMGB2, Oct-1, NF-YA, and GATA-1 to the GFI1B promoter. ChIP analyses were performed with chromatin from undifferentiated shControl- or shHMGB2-transduced UT-7 cells using antibodies against HMGB2, Oct-1, NF-YA, or GATA-1. Quantitative PCRs were performed with 2 pairs of primers, one amplifying a sequence within the GFI1B promoter (−0.15 kb) and the other one amplifying the β2microglobulin promoter. Results are expressed as enrichment values (bound/input) relative to IP with IgG antibody and are means ± SD of 3 independent ChIP experiments; *P < .05 by Student t test.

HMGB2 increases Oct-1 binding to the GFI1B promoter in vitro and in vivo. (A) GATA-1, Oct-1, NF-YA, and HMGB2 binding to the GFI1B promoter in vitro in the presence or absence of HMGB2. Oligonucleotide corresponding to site 1 or site 2 of the GFI1B promoter was incubated with cell lysates from erythroid UT-7 cells. The GATA site of the site 1 and the 3 Gfi-1/Gfi-1B–binding sites of the site 2 oligonucleotides (that bind GATA-1) were mutated when indicated. Cell lysates from UT7 cells infected with shControl or shHMGB2 lentiviruses were used. Total cell extracts were shown (input). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) In vivo binding of HMGB2, Oct-1, NF-YA, and GATA-1 to the GFI1B promoter. ChIP analyses were performed with chromatin from undifferentiated shControl- or shHMGB2-transduced UT-7 cells using antibodies against HMGB2, Oct-1, NF-YA, or GATA-1. Quantitative PCRs were performed with 2 pairs of primers, one amplifying a sequence within the GFI1B promoter (−0.15 kb) and the other one amplifying the β2microglobulin promoter. Results are expressed as enrichment values (bound/input) relative to IP with IgG antibody and are means ± SD of 3 independent ChIP experiments; *P < .05 by Student t test.

We next investigated whether HMGB2 increases the binding of Oct-1 to the GFI1B promoter in vivo. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments were performed in erythroid UT-7 cells knocked down or not for HMGB2. Chromatin was precipitated with HMGB2-, GATA-1–, NF-YA–, or Oct-1–specific antibodies and precipitated DNA was amplified using primers specific or not for the GFI1B promoter. As expected from its ability to bind DNA nonspecifically, HMGB2 bound to the β2m promoter (used as control) as well as to the GFI1B promoter (Figure 3B). In contrast, GATA-1, NF-Y, and Oct-1 associated with the GFI1B promoter exclusively. Remarkably, cells lacking HMGB2 showed decreased binding of Oct-1 to the GFI1B promoter (80% of decrease). A smaller but significant decrease in GATA-1 and NF-Y binding was observed (37% and 40% of decrease, respectively). Thus, HMGB2 is detected at the GFI1B promoter in erythroid cells where it strongly enhances the binding of Oct-1 and, to a lesser extent, of NF-Y and GATA-1 transcription factors.

HMGB2 is required for sustained Gfi-1B expression during erythroid differentiation

Our results show that HMGB2 increases the binding of Oct-1, NF-Y, and GATA-1 to the GFI1B promoter in erythroid cells. We thus hypothesized that this effect of HMGB2 was required for sustained Gfi-1B expression during erythroid development. To test this hypothesis, CD34+ cells were amplified in a 2-phase culture system as described in Figure 1. We found that HMGB2 expression increased along erythroid differentiation of human immature CD34+ progenitor cells (Figure 4A). Indeed, during the amplification phase, the expression of HMGB2 was low at the protein level (D3 and E0) and 2 days after induction of erythroid differentiation (E2). When cells acquired proerythroblast features, HMGB2 protein level increased by 3- to 4-fold. An additional increase in HMGB2 protein level occurred between E2 and E3, and remained high up to E5 (Figure 4A). Interestingly, the HMGB2 expression kinetics paralleled the kinetics of Gfi-1B expression observed during erythroid differentiation.17

HMGB2 expression increases and the knockdown of HMGB2 impedes Gfi-1B expression during erythroid differentiation. (A) HMGB2 protein expression during erythroid differentiation. CD34+ cells were purified from cord blood samples and cultured in a 2-phase system. During the first phase of 5 days (D1 to D5), CD34+ cells were cultured in the presence of IL-3, SCF, EPO, and dexamethasone. Then, the cells were induced to differentiate in the presence of EPO and SCF (E0 to E5). Cell lysates were prepared from CD34+ cells before (D3) and every day after induction of erythroid differentiation (E0 to E5). Total cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using an HMGB2-specific antibody. Actin expression was evaluated to confirm equal protein loading. Data are also expressed (bottom part of the figure) as the ratio between HMGB2 and actin proteins. (B) Experimental protocol for cell transduction and analysis of the effects of HMGB2 depletion. CD34+ cells were purified from cord blood and amplified in the presence of IL-3, SCF, EPO, and dexamethasone and then infected with lentiviruses carrying shControl or shHMGB2 and the puromycin-resistance gene (D1 and D2). Cells were then grown for an additional 48 hours in liquid culture in the culture medium but with addition of 1 μg/mL puromycin. After puromycin selection, cells were induced to differentiate in the presence of EPO and SCF (E0 to E5). (C) Gfi-1B expression during erythroid differentiation in the presence or absence of HMGB2. Cell lysates were prepared from shControl- or HMGB2-transduced cells the day of the induction of erythroid differentiation (E0) and 3 (E3) or 5 (E5) days after. Proteins were analyzed by Western blot using specific antibodies as indicated on the left of the figure; 3 independent experiments were performed.

HMGB2 expression increases and the knockdown of HMGB2 impedes Gfi-1B expression during erythroid differentiation. (A) HMGB2 protein expression during erythroid differentiation. CD34+ cells were purified from cord blood samples and cultured in a 2-phase system. During the first phase of 5 days (D1 to D5), CD34+ cells were cultured in the presence of IL-3, SCF, EPO, and dexamethasone. Then, the cells were induced to differentiate in the presence of EPO and SCF (E0 to E5). Cell lysates were prepared from CD34+ cells before (D3) and every day after induction of erythroid differentiation (E0 to E5). Total cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using an HMGB2-specific antibody. Actin expression was evaluated to confirm equal protein loading. Data are also expressed (bottom part of the figure) as the ratio between HMGB2 and actin proteins. (B) Experimental protocol for cell transduction and analysis of the effects of HMGB2 depletion. CD34+ cells were purified from cord blood and amplified in the presence of IL-3, SCF, EPO, and dexamethasone and then infected with lentiviruses carrying shControl or shHMGB2 and the puromycin-resistance gene (D1 and D2). Cells were then grown for an additional 48 hours in liquid culture in the culture medium but with addition of 1 μg/mL puromycin. After puromycin selection, cells were induced to differentiate in the presence of EPO and SCF (E0 to E5). (C) Gfi-1B expression during erythroid differentiation in the presence or absence of HMGB2. Cell lysates were prepared from shControl- or HMGB2-transduced cells the day of the induction of erythroid differentiation (E0) and 3 (E3) or 5 (E5) days after. Proteins were analyzed by Western blot using specific antibodies as indicated on the left of the figure; 3 independent experiments were performed.

We next assessed whether HMGB2 modified Gfi-1B expression by comparing the expression of Gfi-1B in differentiated erythroid cells in the presence or absence of HMGB2. CD34+ cells were infected twice during the amplification step (D1 and D2) with shControl or shHMGB2 lentiviruses and puromycin-resistant progenitor cells were induced to differentiate toward erythroid lineage in liquid culture in the presence of EPO for 5 days (E0 to E5; Figure 4B and Table 1). HMGB2 was efficiently knocked down at all erythroid differentiation stages (from E0 to E5; Figure 4C). Induction of Gfi-1B expression after induction of erythroid differentiation was significantly impaired in HMGB2-depleted cells (decrease of 60% at E5, Figure 4C). Inhibition of Gfi-1B expression in the absence of HMGB2 was not a consequence of chromatin status modification because the methylation of H3-K4 and H3-K27 and the acetylation of H3-K4/9 were not modified in erythroid cells in the absence of HMGB2 (supplemental Figure 2D). The 2 efficient shRNAs used to deplete HMGB2 had the same effect on Gfi-1B expression and did not modify HMGB1 expression (supplemental Figure 4), indicating that the shRNA used was indeed specific to HMGB2.

Cell numbers (×103) from the 2-phase cultures

| . | Amplification step . | Differentiation step . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D3 . | D5 . | E0 . | E3 . | |

| shControl | 100 | 215 ± 1.5 | 100 | 705 ± 4.9 |

| shHMGB2 | 100 | 270 ± 5.0 | 100 | 517 ± 5.5 |

| . | Amplification step . | Differentiation step . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D3 . | D5 . | E0 . | E3 . | |

| shControl | 100 | 215 ± 1.5 | 100 | 705 ± 4.9 |

| shHMGB2 | 100 | 270 ± 5.0 | 100 | 517 ± 5.5 |

CD34+ cells were plated in the presence of SCF, IL-3, EPO, and dexamethasone then infected with shControl or shHMGB2 48 (D1) and 72 (D2) hours after. Twenty-four hours later (D3) or the day of the induction of erythroid differentiation (D5 = E0) cells were plated at 100 × 103 cells per well and counted in the presence of trypan blue 2 days after.

D indicates day; and E, day after EPO.

Furthermore, having shown that HMGB2 has no sequence specificity and that HMGB2 is necessary for sustained Gfi-1B expression during erythroid differentiation, we studied the physiologic specificity of the HMGB2 binding on another promoter, the GATA-1 promoter. We found that HMGB2 bound to the GATA-1 promoter, but did not enhance the GATA-1 transcription (supplemental Figure 3A-B). However, we observed a decrease in GATA-1 expression in the absence of HMGB2. This decrease was probably due to the absence of Gfi-1B that may stabilize the GATA-1 protein. Indeed, first, Gfi-1B depletion leads to the decrease of GATA-1 expression in erythroid cells (supplemental data 3C-D) and, second, it has been shown that Gfi-1 plays an important role in the stable expression of GATA-3 protein.30 These results strongly suggest that, although HMGB2 does not display sequence specificity for DNA binding, its effect on gene transcription is highly specific. HMGB2 is required for sustained Gfi-1B expression but not directly for GATA-1 expression during erythroid development.

HMGB2 is required for human erythromegakaryocytic maturation

The requirement of HMGB2 for Gfi-1B expression during erythroid differentiation prompted us to investigate whether HMGB2 is indeed essential for the development of hematopoietic progenitors. To address this question, HMGB2-depleted CD34+ cells were plated in semisolid medium to study hematopoietic progenitors or in liquid culture to study terminal erythroid differentiation.

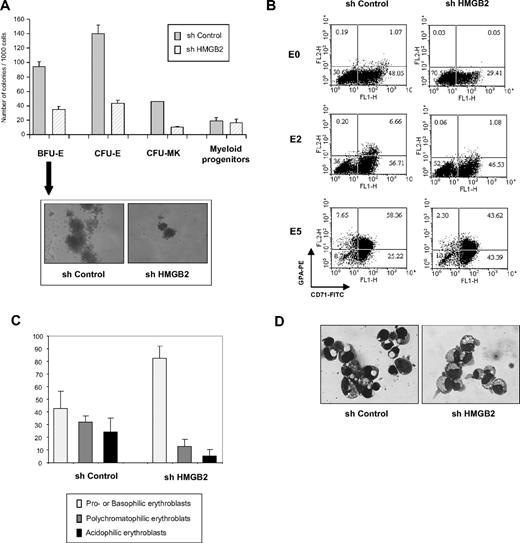

To define whether HMGB2 equally plays a role at early stages of differentiation, the puromycin-resistant cell populations were cultured in methyl cellulose in the presence of a cocktail of growth factors to allow erythroid and granulomacrophagic development or in Megacult medium in the presence of TPO to allow megakaryocytic differentiation. Significantly fewer BFU-E (35 ± 4 vs 94 ± 7 of 1000), CFU-E (56 ± 4 vs 147 ± 17 of 1000), and megakaryocytic (10 ± 1.4 vs 45.5 ± 0.7 of 1000) colonies were observed in HMGB2-depleted cell populations (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the BFU-E colonies that arose from shHMGB2-transduced cells were smaller than those generated from shControl-transduced cells (Figure 5A). Interestingly, HMGB2 and HMGB3 knockdown have opposite effect in immature erythroid progenitor cells.31 Importantly, no difference was observed in the number of granulomacrophagic colonies generated from the HMGB2 knocked-down population (Figure 5A), which does not rely on Gfi-1B for its differentiation.8 Thus, depletion of HMGB2 in immature progenitors profoundly impairs their erythroid development potential.

Depletion of HMGB2 in primary immature progenitor cells impairs their erythroid and megakaryocytic potential. (A) Numbers of erythroid and megakaryocytic progenitors in the presence or absence of HMGB2. CD34+ cells were transduced with shControl or shHMGB2 lentiviruses and puromycin-resistant cells were plated in semisolid medium in methyl-cellulose to determine the number of BFU-Es, CFU-Es, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming units (CFU-GMs) or in Megacult collagen medium for megakaryocyte colony-forming units (CFU-MKs). Colonies were scored 12 to 14 days after plating. Morphology of a representative BFU-E generated by shControl-transduced or HMGB2-depleted cells was shown. (B) Immunophenotypic analysis of shControl- or shHMGB2-transduced cells. Puromycin-resistant cells were induced to differentiate and CD71 and GPA expression was analyzed by flow cytometry before (E0) and 2 (E2) or 5 (E5) days after induction of erythroid differentiation. (C-D) Cytology of the cells. Cytospin samples were prepared from shControl- or shHMGB2-transduced cells 5 days after induction of erythroid differentiation and stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa. Different subpopulations of erythroblasts were characterized under the microscope and the proportion of each subpopulation was evaluated (C). These results are means of 3 experiments with different samples. One example of May-Grünwald Giemsa–stained cytospins of shControl- or shHMGB2-transduced cells using a Leica DXC950P microscope (40×) was shown (D).

Depletion of HMGB2 in primary immature progenitor cells impairs their erythroid and megakaryocytic potential. (A) Numbers of erythroid and megakaryocytic progenitors in the presence or absence of HMGB2. CD34+ cells were transduced with shControl or shHMGB2 lentiviruses and puromycin-resistant cells were plated in semisolid medium in methyl-cellulose to determine the number of BFU-Es, CFU-Es, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming units (CFU-GMs) or in Megacult collagen medium for megakaryocyte colony-forming units (CFU-MKs). Colonies were scored 12 to 14 days after plating. Morphology of a representative BFU-E generated by shControl-transduced or HMGB2-depleted cells was shown. (B) Immunophenotypic analysis of shControl- or shHMGB2-transduced cells. Puromycin-resistant cells were induced to differentiate and CD71 and GPA expression was analyzed by flow cytometry before (E0) and 2 (E2) or 5 (E5) days after induction of erythroid differentiation. (C-D) Cytology of the cells. Cytospin samples were prepared from shControl- or shHMGB2-transduced cells 5 days after induction of erythroid differentiation and stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa. Different subpopulations of erythroblasts were characterized under the microscope and the proportion of each subpopulation was evaluated (C). These results are means of 3 experiments with different samples. One example of May-Grünwald Giemsa–stained cytospins of shControl- or shHMGB2-transduced cells using a Leica DXC950P microscope (40×) was shown (D).

To study terminal erythroid differentiation, HMGB2-depleted CD34+ cells were plated in liquid culture in the presence of EPO. May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining and cytofluorimetry analysis showed that the cells remained immature (CD34+) with no phenotypical changes or morphologic features during the amplification step (D0 to D5-E0); in the presence or absence of HMGB2, the cells stayed immature and were CD34+ (data not shown). However, we observed a defect in terminal erythroid maturation in cells lacking HMGB2: at 5 days after induction of erythroid differentiation, 56.2% (± 15.0%) of control cells were differentiated erythroblasts (polychromatophilic or acidophilic erythroblasts), whereas only 18.0% (± 9.5%) of HMGB2-depleted cells had reached the differentiated erythroblast stages (Figure 5C-D). Furthermore, 82.2% (± 7.9%) of control cells were benzidine positive, whereas only 55.8% (± 8.5%) of HMGB2-depleted cells synthesized hemoglobin. In addition, whereas 66.0% of control cells were positive for glycophorin A (GPA+), only 45.9% of HMGB2-depleted cells expressed the GPA erythroid marker (Figure 5B).

These results show that HMGB2 allows sustained Gfi-1B expression and thereby is essential for erythroid and megakaryocytic maturation.

Discussion

Erythropoiesis involves coordinated expression of regulatory and structural proteins acting in concert to direct the development of immature progenitors into differentiated erythrocytes. Gfi-1B is an important erythroid-specific Gfi-family transcriptional repressor. Inactivation of GFI1B in mice leads to failure of mature erythroid cell production,8 and its forced expression in immature progenitors induces erythroid differentiation in the absence of EPO.9 We have previously shown that Gfi-1B expression increases and remains high all along erythroid differentiation.17 We here identify HMGB2 as a key regulator of GFI1B transcription in erythroid cells. HMGB2 associates with the GFI1B promoter and increases GFI1B transcription by enhancing the binding of Oct-1 and, to a lesser extent, of NF-Y to the GFI1B promoter. Oct-1 in turns potentiates the transactivation of the GFI1B gene by GATA-1. HMGB2 is therefore essential to maintain GFI1B transcription in maturing erythroid cells and to achieve erythropoiesis.

Although HMGB2 binds to DNA with no sequence specificity, it controls the expression of only a limited number of genes.19 Accordingly, we here show that although HMGB2 enhances the transactivation of the GFI1B promoter by GATA-1 and Oct-1, it binds to but does not affect the activity of the GATA-1 promoter. This finding suggests that the architecture of the GFI1B promoter might be essential for HMGB2 function. Interestingly, the GFI1B promoter—but not the GATA-1 promoter—contains 2 tandem sites at a distance of 60 bp, each of which includes both a GATA- and an Oct-binding sequence.32 A model wherein HMGB2 promotes DNA bending at the GFI1B promoter and thereby facilitates the formation of a DNA loop that binds both GATA-1 and Oct-1 can thus be envisioned. Indeed, it has been shown using atomic force microscopy that the association of HMGB proteins to double-strand DNA triggers DNA bending proportionally to HMGB protein concentration,33 and we here show that the levels of HMGB2 increase during erythroid differentiation. In addition, growing evidence in the literature suggests that genes can be configured into looped structures that juxtapose regulatory elements to activate or repress transcription, and combinations of transcription factors have been described to mediate loop formation.34 For example, the interaction of GATA-1 with itself may serve to bring together or stabilize loops between the 2 regulatory elements of the GFI1B promoter. This self-association of GATA was reported to bring together the globin locus control region and the globin promoters.35 However, the precise mechanism of loop formation has not been elucidated. Our work suggests that HMGB proteins may participate in this process.

Furthermore, we propose that HMGB2 potentiates GATA-1–dependent transactivation of the GFI1B promoter in the presence of Oct-1. In this scenario, HMGB2 bends DNA at the GFI1B promoter, facilitating the binding of Oct-1 and its association to GATA-1 for transactivation. A nonexclusive alternative hypothesis proposes that HMGB2 might form a complex with Oct-1 or Oct-1 and GATA-1 before DNA binding, thereby facilitating their association to their target sequences at the GFI1B promoter. Accordingly, it has been shown that the stimulation of the ORF50 promoter by HMGB1 relies on an Oct-1 binding site located at the promoter,36 strengthening the importance of the complex formation before DNA. This might be because HMGB2 requires association with Oct-1 to be efficiently recruited to its target locus. However, our results show that HMGB2 is found at the GFI1B promoter in the absence of Oct-1 and GATA-1, favoring the first model. Whether HMGB2 modifies the 3-dimensional structure of the GFI1B promoter shall now be investigated.

In conclusion, our results show that HMGB2 is an important regulator of GFI1B transcription through its cooperation with the transcription factors GATA-1 and Oct-1 and is therefore essential to erythroid and megakaryocytic development. Interestingly, inactivation of GFI1B,8 GATA-1,37 and Oct-138 leads to a similar phenotype (ie, embryonic lethality due to lack of differentiated erythroid cell production). Our findings further suggest that HMGB proteins might help remodeling the structure of DNA during both erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis and thereby modify the action of the specific transcription factors involved. Accordingly, it has been described that HMGA1 binds to and down-regulates GATA-1 promoter activity and would thereby play a prime role in lymphohematopoietic differentiation from embryonic stem cells.39 Together with ours, these results suggest that the various members of the HMGB protein family might play a key role in the regulation of hematopoiesis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Valerie Bardet (Institut Cochin) for her help in reading cytospin stainings, Dr M. Yamamoto (Tsukuba, Japan) for GATA-1 promoter constructs, Dr Z. F. Chang (Taipei, Taiwan) for wild-type and mutated GFI1B promoter construct, and Dr M. L. Vignais (Montpellier, France) and Dr R. Mantovani (Milan, Italy) for NF-YA expression plasmids. We thank Dr A. M. Lennon-Dumenil (Paris, France) for critically reading and improving the text of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Inserm and by Fondation de France (no. 20077002071). L.B. was supported by a fellowship from ARC (Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer).

Authorship

Contribution: B.L. and V.R.-H. performed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the paper; V.M. and I.D.-F. contributed to research strategy and interpreted data; P.M. performed mass spectroscopy analysis and interpreted data; and D.D. coordinated and performed the research.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dominique Duménil, U567, CNRS (UMR 8104), Institut Cochin, Batiment G Roussy, 27 rue du Faubourg Saint Jacques, 75014, Paris, France; e-mail: dominique.dumenil@inserm.fr.