In this issue of Blood, Moore and colleagues demonstrate that the presence of anti–factor H autoantibodies in aHUS may be associated with the deletion of the CFHR1 gene. In addition, Moore et al provide data further supporting the model that the concurrence of multiple risk factors influences the onset of aHUS.

Intense research in recent years has demonstrated that atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), a rare but devastating disorder characterized by thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and acute renal failure, is associated with mutations and polymorphisms in various components and regulators of the complement alternative pathway (AP) including factor H, factor I, membrane cofactor protein (MCP), factor B, and C3. Mutations altering the C3b/polyanions-binding site located at the C-terminal region of factor H, specifically impairing the capacity of this complement regulator to protect host cells, are the prototypical genetic risk factor associated with aHUS.1 In addition to the genetic alterations in complement proteins, it has been shown that 5% to 10% of aHUS patients present anti–factor H (anti-fH) autoantibodies and that these autoantibodies have functional consequences similar to those caused by the prototypical mutations in the C-terminal region of factor H.2,3 On the basis of these genetic and functional data, it is well established that aHUS is a disease of complement dysregulation. Accordingly, it is believed that in persons carrying the aHUS-associated mutations or developing anti-fH autoantibodies, conditions that trigger complement activation, resulting in deposition and amplification of C3b on the kidney microvasculature endothelial cells, cannot be controlled. This culminates in tissue damage and destruction.

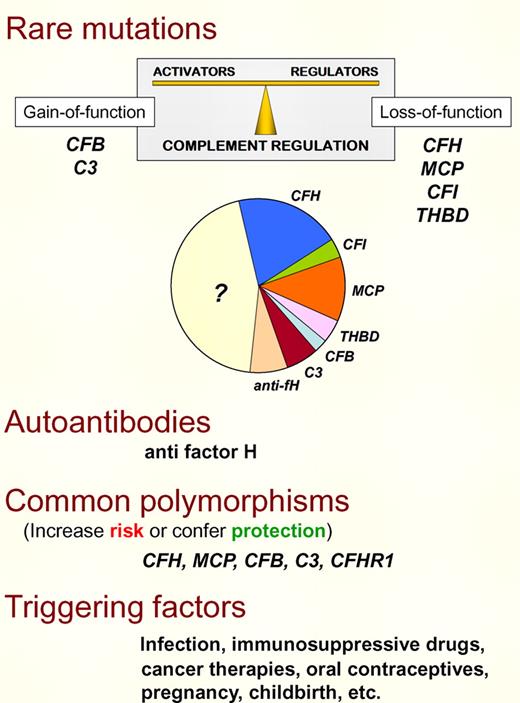

aHUS risk factors. There are several risk factors (genetic and environmental) contributing to aHUS pathogenesis. Rare mutations in the complement alternative pathway (AP) proteins factor H, factor I, MCP, C3 or factor B, and in the coagulation protein thrombomodulin reveal a genetic defect in approximately 50% of aHUS patients. Functional characterization of these mutations has established that aHUS results from complement dysregulation that causes defective protection of cellular surfaces. Importantly, complement dysregulation may result from either a defect in the regulatory proteins (loss-of-function) or an abnormally increased activity of the AP complement components (gain-of-function). Anti–factor H autoantibodies with similar consequences that the complement loss-of-function mutations are present in 5% to 10% of aHUS cases. Common polymorphisms in complement AP proteins also contribute to delineate the genetic predisposition to aHUS, either increasing risk or conferring protection. Finally, triggering factors that activate complement modulate aHUS genetic predisposition. In carriers of multiple strong aHUS genetic risk factors, the contribution of the environment is probably minor. On the other hand, strong environmental factors may compensate for low genetic predisposition.

aHUS risk factors. There are several risk factors (genetic and environmental) contributing to aHUS pathogenesis. Rare mutations in the complement alternative pathway (AP) proteins factor H, factor I, MCP, C3 or factor B, and in the coagulation protein thrombomodulin reveal a genetic defect in approximately 50% of aHUS patients. Functional characterization of these mutations has established that aHUS results from complement dysregulation that causes defective protection of cellular surfaces. Importantly, complement dysregulation may result from either a defect in the regulatory proteins (loss-of-function) or an abnormally increased activity of the AP complement components (gain-of-function). Anti–factor H autoantibodies with similar consequences that the complement loss-of-function mutations are present in 5% to 10% of aHUS cases. Common polymorphisms in complement AP proteins also contribute to delineate the genetic predisposition to aHUS, either increasing risk or conferring protection. Finally, triggering factors that activate complement modulate aHUS genetic predisposition. In carriers of multiple strong aHUS genetic risk factors, the contribution of the environment is probably minor. On the other hand, strong environmental factors may compensate for low genetic predisposition.

Moore et al in this issue of Blood provide clinical data from 13 cases with anti-fH autoantibodies in the Newcastle cohort that further support their relevance in aHUS pathogenesis.4 Most importantly, they show for the first time that some of these aHUS patients also carry mutations (or polymorphisms) in other complement genes previously associated with increased risk for aHUS. Occurrence of multiple different risk factors is relatively common among aHUS patients and has been invoked as an explanation for the incomplete penetrance of aHUS (close to 50%) in carriers of mutations in the complement AP proteins.5 The concurrence of genetic defects and autoantibodies, therefore, reinforces the idea that multiple hits in complement components are necessary for the development of aHUS in some patients. In addition, it indicates that autoantibodies and mutations may contribute in a similar way to aHUS pathogenicity.

Why do some persons develop anti-fH autoantibodies that mimic the aHUS-associated CFH mutations? The available data suggest that there may be a genetic component to the origin of the anti-fH autoantibodies. In fact, it is well documented that they often concur with homozygosity for a 80-kb-long genomic deletion encompassing the CFHR1 and CFHR3 genes.6 Moore et al4 in this issue of Blood and Abarrategui-Garrido and colleagues in a previous one7 analyzed this question in detail and established a specific relationship between the deficiency of the complement factor H–related 1 (CFHR1) protein and the generation of anti-fH antibodies associated with aHUS. This is an intriguing association for which there is now no clear explanation. Interestingly, these autoantibodies recognize the C-terminus of factor H, a region critical for the development of aHUS that is nearly identical in CFHR1, and not surprisingly, they cross-react with CFHR1. Moore et al suggest that deficiency of CFHR1 may result in a failure of central and/or peripheral tolerance to the homologous region in factor H, but there are other possibilities including cross-reactivity with microbial antigens. Answering these questions may require a better understanding of the role of CFHR1. Moreover, searches for additional genetic and environmental factors associated with these autoantibodies may help to explain why despite being the CFHR1 deficiency so frequent in the normal population (∼ 4%), only a few persons develop them.

The available evidence from aHUS patients associates the presence of the anti-fH antibodies with the onset or disease recurrences. The data also suggest that the titer of autoantibodies may spontaneously decline with time. This may explain retrospectively a significant number of aHUS cases for whom no genetic defect in the complement genes has been found and argues for implementing a standardized routine autoantibody screening at the aHUS onset.

Understanding aHUS risk factors is of high potential interest, given the current promises of therapies for aHUS patients. In this respect, it is encouraging that behind the apparent complexity of many different risk factors associated with aHUS, the “autolesion” by complement is envisioned as the single pathogenic mechanism underlying this disorder. This is good news because, in addition to the potential for individual aHUS patients benefiting from specific therapies, inhibitors blocking activation of the complement AP may represent a universal therapy for all of them.

There is still much more to be learned about autoantibodies against complement components. Future studies warrant novel and exciting data that will improve our knowledge of aHUS and other human disorders.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal