Abstract

Enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) is a rare type of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. At present, there are no standardized diagnostic or treatment protocols for EATL. We describe EATL in a population-based setting and evaluate a new treatment with aggressive chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). From 1979 onward the Scotland and Newcastle Lymphoma Group prospectively collected data on all patients newly diagnosed with lymphoma in the Northern Region of England and Scotland. Between 1994 and 1998, records of all patients diagnosed with EATL were reviewed, and 54 patients had features of EATL. Overall incidence was 0.14/100 000 per year. Treatment was systemic chemotherapy (mostly anthracycline-based chemotherapy) with or without surgery in 35 patients and surgery alone in 19 patients. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 3.4 months and overall survival (OS) was 7.1 months. The novel regimen IVE/MTX (ifosfamide, vincristine, etoposide/methotrexate)–ASCT was piloted from 1998 for patients eligible for intensive treatment, and 26 patients were included. Five-years PFS and OS were 52% and 60%, respectively, and were significantly improved compared with the historical group treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy (P = .01 and P = .003, respectively). EATL is a rare lymphoma with an unfavorable prognosis when treated with conventional therapies. The IVE/MTX-ASCT regimen is feasible with acceptable toxicity and significantly improved outcome.

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is the commonest food intolerance disorder in Western populations with a prevalence estimated at 0.5% to 1.0%.1-3 In patients with CD the ingestion of gluten leads to chronic inflammation of the small intestinal mucosa.4 Previously, CD was considered a gastrointestinal disorder of childhood with classical symptoms.5 Currently, it is regarded as a chronic systemic autoimmune disease with a complex clinical picture,5 more commonly diagnosed in adults.1 The only accepted treatment for CD is lifelong elimination of gluten from the diet.5 A small number of patients (2%-5%) fail to improve on a gluten-free diet and are considered to have refractory CD (RCD).6 RCD is classified as type 1, with intraepithelial lymphocytes of normal phenotype, or type 2 with clonal expansion of intraepithelial lymphocytes with an aberrant phenotype.5 Patients with type 2 RCD have a limited life expectancy with a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 50% to 58%.7,8 The main cause of death in these patients is enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL; 88.4%).8

Primary gastrointestinal lymphomas account for 4% to 12% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) and 1% to 4% of all gastrointestinal tumors.9 Primary T-cell gastrointestinal lymphomas are rare. The only defined clinicopathologic entity is EATL4 with an estimated annual incidence of 0.5 to 1 per million people in Western countries.10 EATL occurs primarily in patients in the sixth or seventh decade of life. The commonest presentation is that of reappearance of malabsorption, accompanied by abdominal pain in patients with a history of CD or RCD.4 The relation between EATL and CD is well established.5,7,11-13 However, EATL may also be diagnosed in patients without a history of CD.4 The tumor may occur in any part of the gastrointestinal tract but predominantly arises in the jejunum. In most patients the tumor is multifocal, forming ulcers, nodules, plaques, strictures, or less commonly large masses, often infiltrating the mesentery and mesenteric nodes.4 Treatment options have historically included surgical resection with or without anthracycline-based chemotherapy,9,14 or less commonly high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT).15-17 Results of treatment with surgery or conventional chemotherapy are poor.9 Results with the use of high-dose chemotherapy with ASCT are available only as case reports,16,17 or small series of patients.15 Published data on clinical features of the disease are restricted to small retrospective series, single-center studies,9 or subanalyses.14

Our study aimed to collect prospective data on clinical presentation, treatment, and outcome of patients with EATL in a population-based setting to obtain a more accurate picture of the disease. In addition, we present the results of a novel treatment regimen, prospectively evaluating high-dose chemotherapy with IVE/MTX (ifosfamide, vincristine, etoposide/methotrexate) and ASCT.

Methods

Patient selection

The Scotland and Newcastle Lymphoma Group (SNLG) prospectively collected data on all patients with a diagnosis of lymphoma in Scotland and the Northern region of England (population, circa 7.6 million) beginning in 1979. Total registration of all new cases was achieved during 1994 to 1998.

Records of patients with a new diagnosis of EATL made between 1994 and 1998 were selected for further evaluation. Original histopathologic material was reviewed by hematopathology experts.

From 1998 onward a novel treatment regimen was introduced for patients with a diagnosis of EATL. The treatment decision was made by the group of specialist hematologists. The eligibility criteria for the IVE/MTX-ASCT regimen were de novo EATL, age of 18 years or older, and ability to tolerate high-dose treatment. Patients were discussed at multidisciplinary unit meetings, and all patients who were assigned to receive the new treatment (IVE/MTX-ASCT) were evaluated.

The SNLG complied with the regulations of the Scottish Data Protection Act. Approval for the study was granted by the Therapy Working Party of the SNLG. Informed consent was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collection, response, and toxicity assessment

Data obtained included patient demographics; details of presentation, investigation, and treatment of EATL; toxicity; and patient outcome.

At baseline evaluation extent of disease was assessed by clinical examination, laboratory tests, bone marrow biopsy, endoscopy, and imaging. When appropriate detailed operation notes were available to further inform definitive staging of disease. The extent of disease was recorded with the use of 2 staging systems for primary gastrointestinal lymphomas: Lugano and Manchester scores (Table 1).

Lugano and Manchester scores for gastrointestinal lymphomas

| . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| Lugano score | |

| Stage I | Confined to gastrointestinal tract (single primary or multiple noncontiguous sites of disease) |

| Stage II1* | Local abdominal nodal involvement |

| Stage II2* | Distant abdominal nodal involvement |

| Stage IIE | Serosal penetration to involve adjacent organ or tissues |

| Stage IV | Disseminated extranodal involvement or supradiaphragmatic nodal involvement |

| Manchester score | |

| Stage Ia | Tumour confined to one area of the gastrointestinal tract without penetration of the serosa |

| Stage Ib | Multiple tumors confined to the gastrointestinal tract without penetration of the serosa |

| Stage IIa | Tumor with local nodes histologically involved (gastric or mesenteric) |

| Stage IIb | Tumor with perforation and/or adherence to adjacent structures |

| Stage IIc | Tumor with perforation and peritonitis |

| Stage III | Tumor with widespread nodal involvement (paraaortic or more distant nodes) |

| Stage IV | Disseminated disease involving extralymphatic tissues not adjacent to the tumor (eg, liver, bone marrow, bone, lung, etc) |

| . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| Lugano score | |

| Stage I | Confined to gastrointestinal tract (single primary or multiple noncontiguous sites of disease) |

| Stage II1* | Local abdominal nodal involvement |

| Stage II2* | Distant abdominal nodal involvement |

| Stage IIE | Serosal penetration to involve adjacent organ or tissues |

| Stage IV | Disseminated extranodal involvement or supradiaphragmatic nodal involvement |

| Manchester score | |

| Stage Ia | Tumour confined to one area of the gastrointestinal tract without penetration of the serosa |

| Stage Ib | Multiple tumors confined to the gastrointestinal tract without penetration of the serosa |

| Stage IIa | Tumor with local nodes histologically involved (gastric or mesenteric) |

| Stage IIb | Tumor with perforation and/or adherence to adjacent structures |

| Stage IIc | Tumor with perforation and peritonitis |

| Stage III | Tumor with widespread nodal involvement (paraaortic or more distant nodes) |

| Stage IV | Disseminated disease involving extralymphatic tissues not adjacent to the tumor (eg, liver, bone marrow, bone, lung, etc) |

Combinations such as II1 E and II2 E are also possible.

Evaluation of final response was performed 3 months after the end of treatment (day of operation, last day of chemotherapy, or day of ASCT, whichever was appropriate). Further follow-up was carried out at 3-month intervals during the first year, thereafter at 6-month intervals. All sites of initial disease were reassessed using appropriate techniques.

Complete remission, partial remission, and progressive disease were defined according to the criteria reported by Cheson et al.18 Adverse events were categorized according to the Common Toxicity Criteria of the World Health Organization.

Treatment plan of IVE/MTX-ASCT

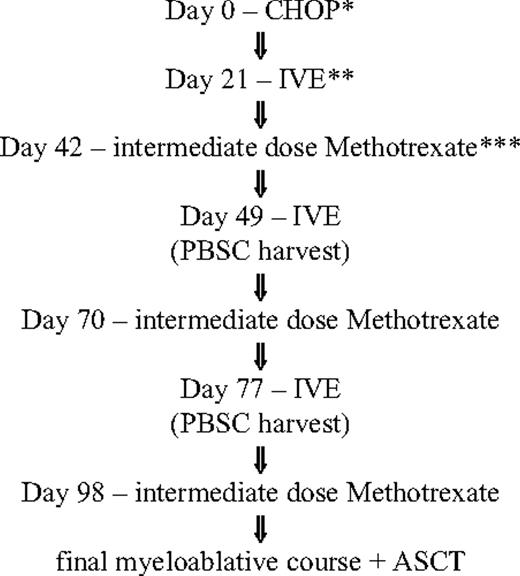

The novel regimen begins with 1 course of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), followed by 3 courses of IVE alternating with intermediate-dose methotrexate. ASCT was performed 4 to 6 weeks after the last course of IVE/MTX if the patient was in remission and sufficient numbers of stem cells had been collected. Stem cell harvesting was performed after the second or third course of IVE (Figure 1). The conditioning regimen was high-dose melphalan/total body irradiation (melphalan, 140 mg/m2 on day 1; total body irradiation, 1200 cGy in 6 fractions over 3 days) or BEAM: carmustine (300 mg/m2 on day 1), etoposide (200 mg/m2 on days 2-5), cytarabine (200 mg/m2 bd on days 2-5), and melphalan (140 mg/m2 on day 6).

Treatment flowchart for IVE/MTX. *CHOP indicates cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2, intravenously, day 1), doxorubicin (50 mg/m2, intravenously, day 1), vincristine (1.5 mg/m2; maximum of 2 mg/m2, intravenously, day 1), and prednisone (40 mg/m2, orally, days 1-5). **IVE indicates ifosfamide (3000 mg/m2, intravenously, days 1-3), epirubicin (50 mg/m2, intravenously, day 1), and etoposide (200 mg/m2, intravenously, days 1-3). ***Intermediate-dose methotrexate (1500 mg/m2, intravenously, day 1).

Treatment flowchart for IVE/MTX. *CHOP indicates cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2, intravenously, day 1), doxorubicin (50 mg/m2, intravenously, day 1), vincristine (1.5 mg/m2; maximum of 2 mg/m2, intravenously, day 1), and prednisone (40 mg/m2, orally, days 1-5). **IVE indicates ifosfamide (3000 mg/m2, intravenously, days 1-3), epirubicin (50 mg/m2, intravenously, day 1), and etoposide (200 mg/m2, intravenously, days 1-3). ***Intermediate-dose methotrexate (1500 mg/m2, intravenously, day 1).

Statistical analysis

Demographics and disease characteristics were summarized with the use of descriptive statistics. The χ2 test, Fisher exact test, and t test were used as appropriate to investigate differences on proportions and means, respectively. OS and progression-free survival (PFS) rates were estimated according to the method of Kaplan and Meier, and comparison between the groups was done with log-rank test. OS was calculated from date of diagnosis to the date of death or, if no death occurred, to the last documented follow-up for the patient. PFS was calculated from date of diagnosis to the first documentation of progression during therapy, failure at the end of therapy, or further relapse or death from any cause during or after the end of treatment. All tests were performed with a confidence interval of 95%, and statistical significance was defined as P less than or equal to .05 with the use of SPSS Version 13.0 (SPSS Inc) for MAC operating system X (Apple).

Results

Between 1994 and 1998, in the population of approximately 7.6 million people in Scotland and the Northern Region of England, 4542 patients were diagnosed with NHL. Fifty-four had features of EATL, giving an overall incidence of 0.14/100 000 per year.

Median age at diagnosis was 57 years (range, 28-82 years), and 21 patients (39%) were women (Table 2). The majority of patients (n = 37; 70%) had extensive disease (defined as Lugano score stages II2, IIE, and IV and Manchester score stages IIb, IIc, III, and IV). Diagnosis of EATL was made in most patients at laparotomy (n = 49; 91%). Computed tomography of the abdomen was abnormal in 25 of 35 patients (71%), ultrasound scanning of the abdomen was abnormal in 8 of 25 patients (33%), chest x-ray was abnormal in 3 of 45 patients (7%), and computed tomography (CT) of the chest was abnormal in 2 of 28 patients (7%).

Characteristics of patients from population-based evaluation (n = 54) and patients treated with IVE/MTX (n = 26)

| . | Population-based evaluation, n/N (%) . | IVE/MTX, n/N (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 57 (28-82) | 56 (36-69) |

| Female sex | 21/54 (39) | 9/26 (35) |

| Lugano stage | ||

| I | 8/53 (15) | 4/26 (15) |

| II 1 | 8/53 (15) | 5/26 (19) |

| II 2 | 6/53 (11) | 2/26 (8) |

| II E | 0/53 (0) | 3/26 (12) |

| II 1E | 0/53 (0) | 6/26 (23) |

| II 2E | 21/53 (40) | 1/26 (4) |

| IV | 10/53 (19) | 5/26 (19) |

| Manchester stage | ||

| Ia | 5/53 (9) | 1/26 (4) |

| Ib | 3/53 (6) | 3/26 (12) |

| IIa | 8/53 (15) | 5/26 (19) |

| IIb | 4/53 (8) | 5/26 (19) |

| IIc | 17/53 (32) | 4/26 (15) |

| III | 6/53 (11) | 3/26 (12) |

| IV | 10/53 (19) | 5/26 (19) |

| Site of disease in GT | ||

| Jejunum/ileum | 52/54 (96) | 22/26 (84) |

| Stomach/duodenum | 0/54 (0) | 2/26 (8) |

| Duodenojejunal flexure | 1/54 (2) | 2/26 (8) |

| Ileocecal | 1/54 (2) | 0/26 (0) |

| Bone marrow involvement | 2/33 (6) | 1/22 (5) |

| ECOG greater than 1 | 46/52 (88) | 20/26 (77) |

| Presenting features | ||

| Pain | 43/53 (81) | 25/26 (96) |

| Lump | 3/53 (6) | 1/26 (4) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2/53 (38) | 18/26 (69) |

| Weight loss | 30/53 (57) | 19/26 (73) |

| Bowel upset | 17/53 (32) | 15/26 (58) |

| Perforation | 21/53 (40) | 8/26 (31) |

| Subacute obstruction | 16/53 (30) | 10/26 (39) |

| Duration of symptoms before diagnosis | ||

| 0-1 mo | 17/51 (33) | 6/25 (24) |

| 1-3 mo | 13/51 (26) | 7/25 (28) |

| 3-6 mo | 15/51 (29) | 5/25 (20) |

| Longer than 6 mo | 6/51 (12) | 7/25 (28) |

| Presence of celiac disease | 48/52 (92) | 19/26 (73) |

| Before diagnosis | 18/52 (34) | 11/26 (42) |

| At diagnosis | 30/52 (58) | 8/26 (31) |

| Diagnosis at | ||

| Surgery | 49/54 (91) | 23/26 (89) |

| Endoscopy | 4/54 (7) | 3/26 (11) |

| Postmortem | 1/54 (2) | 0/26 (0) |

| Abnormal hemoglobin | 27/50 (54) | 11/26 (42) |

| Abnormal WBC count | 18/50 (36) | 9/26 (35) |

| Abnormal kidney function | 16/50 (32) | 11/25 (44) |

| Abnormal liver function | 39/51 (76) | 16/25 (64) |

| Abnormal LDH | 11/26 (42) | 9/19 (47) |

| . | Population-based evaluation, n/N (%) . | IVE/MTX, n/N (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 57 (28-82) | 56 (36-69) |

| Female sex | 21/54 (39) | 9/26 (35) |

| Lugano stage | ||

| I | 8/53 (15) | 4/26 (15) |

| II 1 | 8/53 (15) | 5/26 (19) |

| II 2 | 6/53 (11) | 2/26 (8) |

| II E | 0/53 (0) | 3/26 (12) |

| II 1E | 0/53 (0) | 6/26 (23) |

| II 2E | 21/53 (40) | 1/26 (4) |

| IV | 10/53 (19) | 5/26 (19) |

| Manchester stage | ||

| Ia | 5/53 (9) | 1/26 (4) |

| Ib | 3/53 (6) | 3/26 (12) |

| IIa | 8/53 (15) | 5/26 (19) |

| IIb | 4/53 (8) | 5/26 (19) |

| IIc | 17/53 (32) | 4/26 (15) |

| III | 6/53 (11) | 3/26 (12) |

| IV | 10/53 (19) | 5/26 (19) |

| Site of disease in GT | ||

| Jejunum/ileum | 52/54 (96) | 22/26 (84) |

| Stomach/duodenum | 0/54 (0) | 2/26 (8) |

| Duodenojejunal flexure | 1/54 (2) | 2/26 (8) |

| Ileocecal | 1/54 (2) | 0/26 (0) |

| Bone marrow involvement | 2/33 (6) | 1/22 (5) |

| ECOG greater than 1 | 46/52 (88) | 20/26 (77) |

| Presenting features | ||

| Pain | 43/53 (81) | 25/26 (96) |

| Lump | 3/53 (6) | 1/26 (4) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2/53 (38) | 18/26 (69) |

| Weight loss | 30/53 (57) | 19/26 (73) |

| Bowel upset | 17/53 (32) | 15/26 (58) |

| Perforation | 21/53 (40) | 8/26 (31) |

| Subacute obstruction | 16/53 (30) | 10/26 (39) |

| Duration of symptoms before diagnosis | ||

| 0-1 mo | 17/51 (33) | 6/25 (24) |

| 1-3 mo | 13/51 (26) | 7/25 (28) |

| 3-6 mo | 15/51 (29) | 5/25 (20) |

| Longer than 6 mo | 6/51 (12) | 7/25 (28) |

| Presence of celiac disease | 48/52 (92) | 19/26 (73) |

| Before diagnosis | 18/52 (34) | 11/26 (42) |

| At diagnosis | 30/52 (58) | 8/26 (31) |

| Diagnosis at | ||

| Surgery | 49/54 (91) | 23/26 (89) |

| Endoscopy | 4/54 (7) | 3/26 (11) |

| Postmortem | 1/54 (2) | 0/26 (0) |

| Abnormal hemoglobin | 27/50 (54) | 11/26 (42) |

| Abnormal WBC count | 18/50 (36) | 9/26 (35) |

| Abnormal kidney function | 16/50 (32) | 11/25 (44) |

| Abnormal liver function | 39/51 (76) | 16/25 (64) |

| Abnormal LDH | 11/26 (42) | 9/19 (47) |

IVE/MTX indicates ifosfamide, vincristine, and etoposide/methotrexate; GT, gastrointestinal tract; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; WBC, white blood cell; and LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Forty-nine patients (91%) presented with acute abdominal symptoms, necessitating emergency surgical procedures performed with diagnostic and therapeutic intent. Thirty of those patients (56%) were treated with additional systemic chemotherapy. Five patients (9%) received systemic chemotherapy only and no surgery. Thus, 35 patients were treated with chemotherapy with or without surgery, and 19 patients were treated with surgery alone. The majority of patients treated with chemotherapy (31 of 35) received anthracycline-based chemotherapy: 17 patients received CHOP; 7 patients received cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone, vincristine, and prednisone; and 7 patients received vincristine, doxorubicin, etoposide, prednisolone, cyclophosphamide, and bleomycin. Twenty-three patients (66%) completed their scheduled chemotherapy. The remaining 12 patients (34%) discontinued treatment because of progressive disease or side effects.

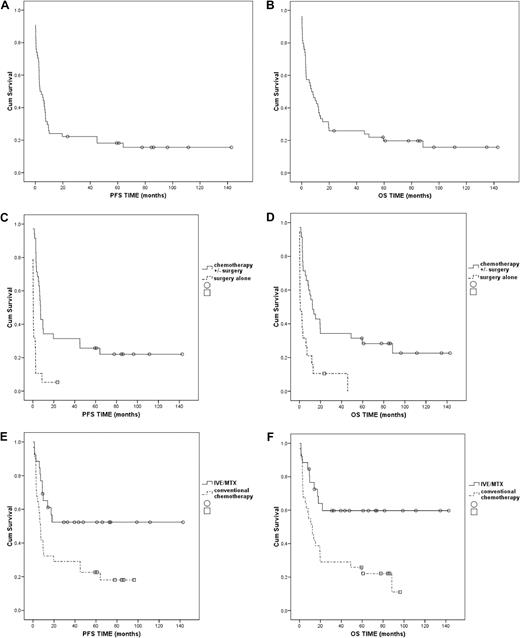

Seventeen patients (32%) achieved remission: 15 patients (43%) among those given chemotherapy with or without surgery and 2 patients (11%) among those treated with surgery alone. The difference between groups was statistically significant (P = .02; Table 3). Forty-four patients died (81%); more in the surgery-alone group (n = 18 patients; 95%) than in the chemotherapy with or without surgery group (n = 26 patients; 74%). Most patients died as a result of disease progression or complications of treatment. For all patients median PFS was 3.4 months and median OS was 7.1 months (Figure 2A-B). Five-years PFS and OS for all patients were 18% and 20%, respectively (Figure 2A-B), and for patients treated with chemotherapy with or without surgery they were 26% and 28%, respectively. None of the patients treated with surgery alone survived at 5 years (Figure 2C-D).

Outcome of population-based evaluation, all patients (n = 54), patients treated with surgery alone (n = 19) vs patients treated with chemotherapy ± surgery (n = 35)

| . | All patients, n (%) . | Surgery alone, n (%) . | Chemotherapy ± surgery, n (%) . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response to treatment | ||||

| CR | 17 (32) | 2 (11) | 15 (43) | .02 |

| Failure | 37 (69) | 17 (89) | 20 (57) | |

| Death | 44 (81) | 18 (95) | 26 (74) | .08 |

| . | All patients, n (%) . | Surgery alone, n (%) . | Chemotherapy ± surgery, n (%) . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response to treatment | ||||

| CR | 17 (32) | 2 (11) | 15 (43) | .02 |

| Failure | 37 (69) | 17 (89) | 20 (57) | |

| Death | 44 (81) | 18 (95) | 26 (74) | .08 |

CR indicates complete remission.

Patients treated with surgery alone vs patients treated with chemotherapy ± surgery.

Kaplan-Meier plots for PFS and OS. (A) Progression-free survival (PFS): population-based evaluation, all patients (n = 54). (B) Overall survival (OS): population-based evaluation, all patients (n = 54). (C) PFS: population-based evaluation, patients treated with surgery alone (n = 19) versus patients treated with chemotherapy with or without surgery (n = 35); P < .001. (D) OS: population-based evaluation, patients treated with surgery alone (n = 19) versus patients treated with chemotherapy with or without surgery (n = 35); P < .001. (E) PFS: patients treated with IVE/MTX (n = 26) versus patients treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy from population-based evaluation (n = 31); P = .01. (F) OS: patients treated with IVE/MTX (n = 26) versus patients treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy from population-based evaluation (n = 31); P = .003

Kaplan-Meier plots for PFS and OS. (A) Progression-free survival (PFS): population-based evaluation, all patients (n = 54). (B) Overall survival (OS): population-based evaluation, all patients (n = 54). (C) PFS: population-based evaluation, patients treated with surgery alone (n = 19) versus patients treated with chemotherapy with or without surgery (n = 35); P < .001. (D) OS: population-based evaluation, patients treated with surgery alone (n = 19) versus patients treated with chemotherapy with or without surgery (n = 35); P < .001. (E) PFS: patients treated with IVE/MTX (n = 26) versus patients treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy from population-based evaluation (n = 31); P = .01. (F) OS: patients treated with IVE/MTX (n = 26) versus patients treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy from population-based evaluation (n = 31); P = .003

In view of the dismal outcomes obtained with conventional CHOP-like chemotherapy, from 1998 onward 26 patients were treated with the novel regimen in 7 centers around the United Kingdom.

Patient characteristics at baseline were similar to those of patients in the population-based evaluation (Table 2). In our experience the novel treatment can be tolerated by most patients presenting with EATL. During the study time 17 patients presented with a diagnosis of EATL to the Newcastle Hospitals Lymphoma Multidisciplinary Team (the primary site where the protocol was initiated), and 12 patients (71%) were enrolled. The remaining 5 patients were excluded from the new protocol because of advanced age in 3 cases and poor general condition in 2 (failure to recover from primary surgery).

The median age was 56 years (range, 36-69 years). Nine patients (35%) were women. The majority of patients (n = 17; 66%) presented with extensive disease (Lugano stage II E, II1 E, II2 E, and IV or Manchester stage IIb, IIc, III, and IV).

In 3 patients MTX was omitted from the scheduled chemotherapy because of kidney insufficiency or poor general condition. Five patients discontinued treatment prematurely; 4 because of toxicities (1 for severe sepsis and death, 1 for severe encephalopathy, 1 for bone marrow failure, and 1 for gastrointestinal bleeding), and the other patient progressed after the initial cycle of CHOP. Of the remaining 21 patients, 14 went on to receive ASC transplant. The conditioning regimen was high-dose melphalan/total body irradiation in 7 of 13 patients (54%) and BEAM in 6 of 13 patients (46%). The source of stem cells was peripheral blood in the majority of patients (11 of 13 patients [85%]) and bone marrow in 2 of 13 patients (15%). Data on number of CD34+ stem cells re-infused was available in 11 patients, and the median number was 6.0 × 106/kg with the range from 1.0 × 106/kg to 14.8 × 106/kg. Information on growth factor use after ASCT was available in 10 patients, and 5 patients (50%) received granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. ASCT was omitted because of refractory disease in 3 patients, poor general condition in 2 patients, insufficient stem cell mobilization in 1 patient, and 1 patient declined further treatment. Importantly, there was no statistically significant difference in the number of patients who discontinued treatment between patients treated with IVE/MTX-ASCT and the historical group of 31 patients treated with a CHOP-like regimen (54% vs 65%; P = .43).

The toxicity profile was acceptable for an intensive regimen. The most common toxicities were infection/sepsis in 14 patients (54%). Other severe toxicities affecting 1 patient each were encephalopathy, bone marrow failure, gastrointestinal bleeding, and chronic renal failure. Six patients had disease-related complications during treatment, 4 intestinal obstruction and 2 perforation.

Treatment results of IVE/MTX-ASCT were compared with the results of the historical control group treated with conventional anthracycline-based chemotherapy from our population-based evaluation. There was no statistically significant difference between both groups according to age, sex, and features at presentation except for a greater number of patients presenting with nausea/vomiting (P = .04) and a lower number of patients with diagnosed CD (P = .02). Patients given IVE/MTX-ASCT had an improved remission rate compared with patients treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy (69% vs 42%; P = .06; Table 4). Death rates were significantly lower in patients treated with IVE/MTX-ASCT compared with patients treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy (39% vs 81%; P = .001). In both groups the most patients died as a result of underlying disease. Among the 14 patients who received a transplant, 2 died as a result of non–disease-related reasons: 1 because of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia 4 months after ASCT and 1 because of sepsis and recurrent chest infections 12 months after stem cell transplantation. Five-year PFS and OS were significantly higher in patients receiving IVE/MTX-ASCT than in those treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, (PFS: 52% vs 22%, P = .01; OS: 60% vs 22%, P = .003; Figure 2E-F).

Outcome of patients treated with IVE/MTX (n = 26) versus patients treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy from population-based evaluation (n = 31)

| . | IVE/MTX, n (%) . | Anthracycline-based chemotherapy, n (%) . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response to treatment | |||

| CR | 17 (65) | 13 (42) | .06 |

| PR | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Failure | 8 (31) | 18 (58) | |

| Death | 10 (39) | 25 (81) | .001 |

| Death from lymphoma | 8 (31) | 19 (61) | .005 |

| . | IVE/MTX, n (%) . | Anthracycline-based chemotherapy, n (%) . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response to treatment | |||

| CR | 17 (65) | 13 (42) | .06 |

| PR | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Failure | 8 (31) | 18 (58) | |

| Death | 10 (39) | 25 (81) | .001 |

| Death from lymphoma | 8 (31) | 19 (61) | .005 |

IVE/MTX indicates ifosfamide, vincristine, etoposide/methotrexate; CR, complete remission; and PR, partial remission.

Patients treated with IVE/MTX versus patients treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy from population-based evaluation.

In the evaluation of patients who entered the protocol and completed the scheduled treatment and those who failed to complete it, the number of patients with complete remission and partial remission was statistically significantly higher in the former group than in the latter: 13 patients (93%) versus 5 patients (41%); P = .004, respectively. There were fewer deaths and EATL-related deaths in the group that completed the protocol compared with the group that did not; however, the differences were not statistically significant: 4 (29%) and 2 (14%) versus 6 (50%) and 6 (50%); P = .422 and P = .09, respectively. The 5-years PFS and OS were both 68% for patients who completed the whole treatment and 33% and 50% for patients who did not; the difference is statistically significant for PFS (P = .028) but not for OS (P = .251).

Discussion

The incidence of EATL in our population-based evaluation was 0.14/100 000 per year, and EATL comprised 1.4% of all registered NHLs. The median age of patients was 57 years, and the majority of patients were men (61%). The results of another population-based study by Verbeek et al1 are comparable with ours, showing an incidence of EATL of 0.10/100 000 per year, with a reported median age of 64 years and 64% of patients were men. As previously reported, the majority of our patients presented with reduced performance status (88% Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score > 1) mainly because of the high numbers of patients with acute abdominal symptoms and poor nutritional status.9 In our study, as in the retrospective series published by Gale et al,9 the diagnosis was predominantly made at laparotomy, and the pattern of presenting symptoms was comparable, namely, pain, nausea/vomiting, and weight loss.

Sixty-five percent of patients from the population-based evaluation were treated with chemotherapy and 35% with surgery alone. These results are similar to those previously published by Gale et al9 and Daum et al.14 One reason for withholding chemotherapy was the poor condition of patients after surgery. In addition, the median age of patients treated with surgery alone was significantly higher than patients treated with systemic chemotherapy with or without surgery. As in published studies, only approximately half of our patients completed their scheduled chemotherapy; the main reasons for discontinuation being refractory disease and toxicity.9,14

The outcome of the whole group in the population-based evaluation was very poor; 81% died and the median PFS and OS were 3.4 months and 7.1 months, respectively. Patients treated with chemotherapy with or without surgery had a significantly better outcome than patients treated with surgery alone. Because of the lack of published data on survival of patients treated with surgery alone, further comparison is impossible. However, the outcome for patients treated with chemotherapy with and without surgery was comparable with that previously reported.9,14

We have described the role of high-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT for the primary treatment of EATL in a cohort of representative patients. The outcome of patients treated with high-dose chemotherapy and ASCT reported previously varies from no response to remissions lasting longer than 32 months.15-17,19,20 In some cases the ASCT was performed in first remission15 and in some in second and subsequent remissions,16,17 or the remission status was not specified.20 Therefore, it is difficult to make any valid conclusions. Generally, the patients were treated with several cycles of anthracycline-based chemotherapy followed by a myeloablative ASCT.

The high number of patients failing conventional anthracycline-based chemotherapy mainly because of primary refractory disease/disease progression and toxicity9,14 prompted the SNLG to reconsider its approach to this difficult group of patients. Our promising results with the use of IVE in patients with refractory/relapsed lymphomas21-23 encouraged us to introduce this regimen as the first-line treatment of choice for patients with EATL. We added intermediate-dose MTX to the protocol as prophylaxis against previously described relapse/progression of disease in the central nervous system.24,25 Treatment starts with 1 cycle of CHOP to establish initial disease control; to minimize the risk of side effects such as perforation, anastomotic breakdown, or wound dehiscence (in the postsurgery patient); and to allow a limited recovery period before the more intensive part of the regimen begins.

The new treatment was generally well tolerated compared with reports of anthracycline-based therapies from our group and other studies.9,14 Most patients benefit from parenteral nutrition at least initially. The toxicity profile was similar to those described in the literature for high-dose chemotherapy regimens with ASCT.15-17 However, as expected, there was a higher incidence of neutropenic fever and sepsis compared with anthracycline-based chemotherapy.9,14 Significantly, stem cell harvest after IVE was successful in all except 1 patient, and engraftment was successful in all patients who received a transplant.

Patients treated with the novel regime had higher remission rates and lower mortality compared with patients receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy from our population-based study (P = .06 and P = .001) and with series of patients treated with ASCT from other studies.9,14 Observed remissions, lasting up to 143 months, are longer than other published data on patients treated with ASCT.15-17 The 5-year PFS and OS were also significantly higher compared with the group of patients treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy from our population-based evaluation (P = .01 and P = .003, respectively) and from other studies.9,14

Patients developing de novo EATL without a previous history of CD present no treatment dilemmas, and we have described improved results with our intensive approach. By contrast, the time to initiate treatment in patients with RCD type II is controversial. Some investigators suggest the early introduction of therapy before a diagnosis of EATL8 because large numbers of patients with RCD type II will develop EATL.8 In addition, treatment of established EATL is associated with increased complications.14 In our opinion, the IVE/MTX-ASCT is a very powerful regimen with potentially severe toxicities and should be reserved for patients with a confirmed diagnosis of EATL. Future studies should evaluate techniques for early diagnosis of EATL in patients with RCD type II, for example, capsule endoscopy, CT,26 or positron emission tomography–CT.27 No simple effective treatment has yet been shown to prevent development of EATL in such patients, but promising results are reported.28

In conclusion, EATL is a rare lymphoma with a dismal prognosis when treated with conventional treatment. Patients with EATL should be treated with systemic chemotherapy. The results of our new aggressive treatment IVE/MTX-ASCT are promising. We recommend patients should be entered into national studies such as National Cancer Research Institute 1418 in the United Kingdom to evaluate this approach further in a wider multicenter setting.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank SNLG colleagues for releasing clinical records of patients for prospective study; Dr James Henry and Dr Bob Jackson for histologic review of patients samples; and Jo White for advice on statistical issues and updating of data.

Authorship

Contribution: A.L.L. designed the study, performed the population-based study, reviewed all data, and reviewed the manuscript at all stages; M.S. analyzed data and prepared the manuscript; A.L.L., R.C., J.D., P.F., S.L., P.M., P.R., F.J., K.B., and S.J.P. treated the patients; A.L.L., M.S., N.A., R.C., J.D., P.F., S.L., P.M., and P.R. documented patients in the new study. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michal Sieniawski, Haematological Sciences, Newcastle University, Leech Bldg, Medical School, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE2 4HH, United Kingdom; e-mail: michal.sieniawski@ncl.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal